In plural societies1 social welfare can be a terrain of political contestation, particularly when states fail to provide basic public goods and social services. In the Middle East, South Asia, and other developing regions, ethnic or religious organizations use service provision as a means of building support; welfare therefore is an integral component of ethnic and sectarian politics. It is well established that more homogeneous communities have superior public goods provision and, by extension, that ethnic or religious groups tend to favor in-group members in distributing social benefits.2 But such organizations may also cater to out-group members: under what conditions do ethnic or religious groups serve beyond their own communities?

This article explores this question in Lebanon, where political organizations with sectarian3 orientations play a crucial role in meeting the basic needs of the population. We find, however, that these different sectarian parties and movements have varied propensities to serve out-group communities. To bring this puzzle into stark relief, we focus on the two largest and most well financed political organizations in Lebanon, the predominantly Sunni Muslim Future Movement and the Shiite Muslim Hezbollah. Although they operate under the same national institutional rules and boast the largest welfare programs in their respective communities, both organizations also target out-group communities to varying degrees. While the Future Movement aims to serve a broader array of beneficiaries, including non-Sunnis, Hezbollah focuses relatively more on Shiite communities, but not exclusively.

We argue that distinct political mobilization strategies—whether electoral or nonelectoral—primarily explain different patterns of Future Movement and Hezbollah welfare outreach across sectarian lines. The logic of electoral competition and its relationship to the distribution of benefits is relatively straightforward: when parties pursue and prioritize electoral mobilization, which requires them to induce citizens to go to the polls and to win sufficient votes to hold public offices, they are most likely to target out-group voters.4 Depending on the precise nature of electoral rules and districts, the desire to win elections provides direct incentives to parties to court out-group voters, particularly when the in-group population in a given district “is too small to be efficacious.”5 For example, in Lebanon’s party bloc electoral system based on joint electorates with reserve seats, voters choose candidates from all sects represented in their districts and therefore parties at least theoretically must appeal to out-group voters. Accordingly, we focus on the strategies of sectarian parties on the subnational, district level—and not just on the national level. Because the “cultural demography”6 of voter populations varies from district to district, parties behave differently with voters from the same sects in different electoral units.

Not all parties, however, prioritize electoral competition exclusively. Where political institutions are weak or contested, such as in Lebanon and elsewhere in the Middle East, South Asia, and other developing regions, electoral incentives do not fully structure political life. We argue therefore that the degree to which sectarian parties cater to members of out-groups not only depends on electoral incentives but also reflects a prior question—that is, whether parties emphasize alternative, nonelectoral forms of competition such as mobilizing communities to engage in civil protests, mass demonstrations, and, in the extreme, riots or even militia warfare. These forms of competition are particularly salient in nonconsolidated democracies, quasi democracies, or electoral authoritarian systems, where parties play a “dual game,” including an electoral game, in which they aim to gain vote share, and a “regime game,” in which they struggle over the basic rules of allocating power in the polity.7 In these contexts, the goal of modifying the distribution of power conditions organizational behavior and strategy while the electoral arena is often not the main site of competition over changes in political rules. Rather, competition can occur outside of formal institutionalized channels and spill over into street protests or violent clashes, which sway the outcomes of elite negotiations over the allocation of power in the polity. Furthermore, not all parties—even those that operate in the same national context—favor the same modes of political competition. While some focus their strategic efforts on building electoral support, others may place more weight on grassroots mobilization or militia competition as a way to signal their power and push their demands. This variation in strategies of political mobilization, we argue, is central to understanding distinct patterns of allocating social benefits to out-group members.

The next two sections of the article distinguish our argument from alternative approaches and develop the logic of our claims in more detail. Subsequent sections present the quantitative and qualitative evidence for our claims. Drawing on an original Geographic Information Systems (gis) data set of 480 clinics, 164 hospitals, and 1,393 private schools in Lebanon, we begin with descriptive spatial data to show variation in welfare outreach strategies across Future Movement and Hezbollah. Next, we employ a basic statistical model to examine the relationship between the location of welfare agencies established by the two parties and population characteristics. To flesh out the political motivations for social welfare provision, we draw on data from over three hundred in-depth interviews with elites, such as providers and party officials, and beneficiaries of diverse social programs, as well as from archival and other published sources. We illustrate our arguments with reference to four brief case studies of in-group and out-group communities where the Future Movement and Hezbollah have and have not established welfare agencies.

Sectarianism and Social Welfare

The idea that political strategies shape the distributional behavior of sectarian parties differs from a variety of alternative explanations. First, an implicit assumption of journalistic accounts of ethnic and religious party behavior—and of critics of such parties—is that that these organizations merely serve “their own.” This interpretation holds that sectarian organizations exist solely to cater to their own communities, implying that they are not responsive to political incentives.8 Similarly, some maintain that ideological motivations such as the desire to implement an Islamic state, rather than shorter-term political calculations, guide the social relations of sectarian parties.9 The fact that the Future Movement and even Hezbollah, the more overtly religious of the two organizations, both serve out-groups and respond to electoral incentives undercuts the value of an ideological explanation.

From a distinct vantage point, recent economistic studies of “terrorist” organizations also suggest that sectarian organizations exist to serve their own. Based on deductive models, this approach holds that the provision of social welfare is a means of building organizational resilience by controlling defection.10 This interpretation, however, presents an overly stylized vision of sectarian organizations that neglects the nonviolent forms of political competition that motivate sectarian institutions to provide welfare services. As our arguments and empirical evidence suggest, sectarian parties are responsive to both formal and informal institutional incentives in the polities in which they operate. The allocation of benefits is a function of party strategies, which should be explained rather than assumed ex ante.

A second set of accounts recognizes the political calculations of ethnic or sectarian organizations but holds that formal institutions such as power-sharing arrangements do not operate as anticipated, given the realities of informal politics. Even electoral systems that are explicitly designed to encourage intergroup cooperation, such as Lebanon’s joint electorates with reserve seats, do not function as intended because preelectoral bargains among elites from different sects obviate the need to cater to out-group voters.11 While there is much merit to this argument, our evidence indicates that parties make efforts to serve out-group members in some electoral districts and, therefore, that elite arrangements do not uniformly undercut the incentive to compete for votes throughout the national territory.

A third alternative explanation focuses on resource endowments, which might shape the distribution of benefits in distinct ways. One perspective holds that parties channel “leftover benefits” to out-group members when they have surplus resources.12 But our research on Lebanon indicates that even the most well endowed parties are not always generous with in-group members,13 even as they target selected out-group areas with benefits. This reality calls for greater analytical attention to variation in the distribution of benefits to in-group as well as out-group members.

Another perspective implies that resource-rich groups are more autonomous from local populations and therefore do not need to develop cooperative relationships with civilians.14 Paradoxically, this approach suggests that wealthier organizations are less likely to distribute welfare benefits. Variation in the propensity to target out-group members, even among resource-rich organizations such as the Future Movement and Hezbollah, indicates that other factors beyond access to material resources explain patterns of distributing welfare benefits. At a minimum, adequate resources are a necessary but not sufficient condition for the provision of expensive health, education, and other social benefits by sectarian parties. Furthermore, social welfare institutions arguably require place-specific resources, such as volunteers, and therefore require providers to develop close ties with the community regardless of financial resource endowments.

Finally, the organizational structures and practices of different religious sects might explain their varied propensities to serve both in-group and out-group members. For example, some depict the clergy-follower relationship as more hierarchical in Shiite practice than in Sunni practice.15 This more structured relationship might reduce the need to provide benefits to in-group members as a means of bolstering popular allegiance to the leadership of Shiite organizations. Nonetheless, Shiite parties such as Hezbollah do offer extensive benefits to in-group members, although the propensity to do so varies over time, showing that sect-specific institutions, which evolve more slowly, do not determine the distributive practices of sectarian parties.

Political Competition and Social Welfare by Sectarian Parties

To explain why identity-based organizations might actively woo out-group members, we point to the political strategies of sectarian parties. We assume that sectarian parties—like all political actors—seek to maximize their control over state institutions, an assumption that both accords with the stated goals and behavior of parties in Lebanon and, at the same time, does not deny the altruistic and even religious commitments of leaders and cadres in sectarian parties. Sectarian parties may employ diverse strategies to pursue this goal, including both electoral and nonelectoral approaches.

Turning first to electoral mobilization, we concur with existing research16 that formal electoral rules can compel ethnic or sectarian parties to serve out-group members: despite preelectoral bargains among elites, Lebanon’s electoral system, in which voters cast ballots for all candidates irrespective of sectarian identity, compels parties to win out-group votes, particularly in more heterogeneous districts and where out-group members constitute a significant portion of the electorate.17 At the same time, we expect that a party’s behavior toward out-group members varies from district to district depending on its strategic interests, which are shaped by the cultural demography of the voter populations. Where out-group members constitute important voting blocks, parties are more likely to cater to them.

But short-term electoral considerations are not the sole motivating factor, in part because political actors know that electoral rules are subject to change. The potential longer-term need to court out-group members in revised districts might compel parties to demonstrate “good governance” credentials or to try to build a reputation for being able to rule effectively and represent the public good beyond narrow sectarian considerations. Because they aspire to hold national political power, parties that prioritize electoral mobilization have an incentive to show that they are capable of representing both in-group and out-group communities. Thus, we expect electoral considerations—whether premised on short- or long-term calculations—to be associated with greater propensity to serve out-group communities.

Second, we move beyond electoral incentives by arguing that non-electoral strategies of political mobilization take precedence or are equally important for some parties. Nonelectoral strategies include nonviolent tactics such as sit-ins, protests, or demonstrations, as well as violent tactics such as organizing riots or militias. These forms of mobilization compel parties to concentrate benefits on a smaller group of core activists, who galvanize community participation in mass protests or serve as militia fighters. By contrast, electoral politics entails reliance on a more diffuse set of temporary, local volunteers to rally voter turnout, as well as on ephemeral relationships with voters through vote-buying arrangements.

Nonelectoral competition is relatively underemphasized in recent studies of clientelism and vote buying,18 but in nonconsolidated democracies or electoral authoritarian systems parties play a “dual game”19 in which elections are but one arena of competition. In these contexts political organizations may adopt a more fundamental goal, namely, to modify the very rules of allocating political power. In this “regime game,” competition occurs outside of formal institutionalized channels, for example, through street protests or violent clashes. The ability to mobilize large numbers of supporters—or even small but very committed groups of supporters—and to do so in a relatively short time frame signals grassroots power, an important tool for influencing elite-level negotiations over electoral and other formal institutional rules. In nonelectoral mobilization a narrow group of cadres is critical both for mobilizing neighborhood and village participation in mass events and for establishing their willingness to turn out on a moment’s notice to take part in smaller protests and riots. In some polities, political organizations maintain militia forces, which draw on a committed group of core supporters who are prepared to make the ultimate sacrifice. To help maintain this commitment, sectarian parties establish the most comprehensive welfare programs for militia fighters and their families.20 We expect that parties engaging in nonelectoral competition would target social benefits to a narrower group of supporters, who tend to come from in-group communities, and therefore would place less emphasis on reaching out to out-group communities.

Our focus on the electoral versus nonelectoral motivations of social provision raises the question of why sectarian parties adopt varied strategies of political mobilization in the first place. We argue that this choice can be understood only through contextualized knowledge of the origins and evolution of specific parties and therefore cannot be derived ex ante. While the Future Movement capitalized on a virtual power vacuum in its base community of Sunnis, who have enjoyed a position of relative privilege in the Lebanese polity since independence and earlier, Hezbollah emerged as a militia force devoted to resisting Israeli occupation, catered to the historically marginalized Shiite population, and initially faced competition from other Shiite political and religious groups. From its inception, the Future Movement, which evolved out of the political machine of the family of Rafiq al-Hariri, the assassinated former prime minister of Lebanon, focused on winning electoral support. Hezbollah maintained its militia and continued to emphasize mass mobilization in the postwar period, following the civil war of 1975–90, but gradually engaged in electoral politics in some districts.21 In the next section we justify the use of location of welfare agencies as a proxy for the distribution of benefits and describe our case selection, data, and research methods.

Spatial Analysis and Bricks and Mortar Clientelism in Plural Societies

The locations of sectarian party welfare institutions provide an appropriate measure of targeting strategies, or the communities that parties seek to serve. There are few if any legal or practical restrictions on the locations of private institutions,22 providers acknowledge that they purposively target specific communities with welfare programs,23 and beneficiaries interpret the locations of party-based welfare agencies as evidence for territorial and communal favoritism of sectarian organizations. 24 Furthermore, given the sensitivities of sectarian politics in Lebanon, parties claim that they do not collect data on the religious identities of welfare beneficiaries; therefore an alternative measure of the dependent variable is required.

In plural societies ethnic or religious groups tend to concentrate geographically—at a minimum at the level of urban neighborhoods or villages if not at higher aggregations. Through a combination of local knowledge and official records, parties are aware of fine-grained differences in cultural demography and are capable of targeting benefits to specific ethnic or religious communities with precision. Furthermore, interviews and data from a national survey on access to social welfare in Lebanon show that individuals and families seek and accept services from out-group providers, particularly when they are geographically proximate.25

A spatial analysis of sectarian welfare institutions is also justified on theoretical grounds. Our focus on “bricks and mortar” institutions, or the physical structures of service delivery, adds a distinct dimension to contemporary studies of clientelism, which largely focus on the distribution of mobile benefits such as food or cash that are not as rooted in specific places.26 Bricks and mortar clientelism signals a commitment to a community, facilitating a sense of solidarity and building or reinforcing boundaries of who belongs. This is especially meaningful in plural societies, where different territories are associated with stable endowments of cultural communities, often with corresponding party organizations, religious charities, or communal associations that demarcate their areas of control with posters, banners, and other symbols. High-fixed-cost projects, embodied in physical structures, equipment, and regular personnel, show a party’s willingness to invest in a community, rendering out-group service provision all the more surprising and meaningful. To the extent that organizations rely on their own resources— and not just on state patronage—this investment is particularly significant. Furthermore, in much contemporary research on patronage and clientelism, the state is the primary source of benefits. In Lebanon and other weak states, however, nonstate actors play an important role in providing resources. The next section describes the cases and spatial data used in the analyses.

Case Selection, Data, and Methods

Subnational comparison of sectarian parties in Lebanon enables an analysis of social service provision as a strategy for political mobilization. The Lebanese welfare regime involves minimal state provision and regulation, leaving wide scope for private, nonstate actors to supply basic services.27 Sect-based welfare has a long lineage in Lebanon, dating back to the Ottoman period, and has persisted in various forms from independence in 1943 to the present. The emergence of welfare provision linked to political parties and movements is largely a legacy of the civil war (1975–90), when militias offered services to fighters and civilians residing in the territories they controlled. In the postwar period, militias transformed themselves into political parties and institutionalized parallel social service and political wings while new parties emerged.28 At present, about half of Lebanon’s schools, hospitals, and clinics operated by nonstate organizations are run by religious charities or political parties with sectarian orientations. Out of a total of about 3,070 institutions, approximately 1,660 qualify as nonstate organizations because they are not directly administered by the public sector. The state is most involved in schooling as a direct provider: in 2005, 1,399 out of 2,792 schools were public. The state plays a negligible role in running health care institutions: in 2006, only about 5 out of 160 hospitals were government run and about 10 percent of Lebanon’s approximately 453 registered health care clinics were officially run by public agencies. Furthermore, many ostensibly public health care institutions are actually controlled by political parties or community groups.29

Within Lebanon the predominantly Sunni Future Movement and the largely Shiite Hezbollah are appropriate for structured comparison. Beyond the fact that they operate under the same electoral rules, the two organizations are major players in national politics, emphasize their national credentials while stressing their linkages to particular sectarian communities,30 command large resources to fund vast social service initiatives, and play a critical role in social welfare provision in low- and middle-income communities throughout the country.31 At particular times in the life cycles of these organizations, however, the two parties have adopted distinct strategies for allocating welfare, with the Future Movement reaching out more frequently across sectarian lines and Hezbollah focusing more on in-group communities.

We use the spatial locations of Future Movement and Hezbollah welfare institutions and associated population characteristics to measure the parties’ targeting strategies, our dependent variable. The institutional data were collected at a small unit of analysis: administrative divisions within Lebanon, which is only about 10,400 square kilometers, or 70 percent of the size of the U.S. state of Connecticut,32 include six provinces (mohafaza) (Beirut, Mount Lebanon, North, Bekaa, Nabatiyya, and South). These provinces collectively contain 24 districts (qada), which are further subdivided into 1,633 zones (mantaqa ‘iqariyya). Zones are not arbitrary administrative units but rather correspond to named neighborhoods or villages, which have real meaning to residents. Electoral boundaries build on these divisions. Thus, in the 2005 and 2000 national elections, the fourteen electoral districts corresponded to qada boundaries, although a few encompassed more than one qada, while the 2008 electoral law reduced the size of some districts to use the qada as the main electoral district. The city of Beirut, which is divided into twelve neighborhoods that encompass sixty zones, contains three electoral districts.

Given sensitivities in a country where political power is allocated ex ante on the basis of sectarian identity, the last official census was conducted in 1932 and therefore population data are limited. Estimates of the population proportion of the main religious groups range from 39 to 43 percent Christian of various sects, 25 to 35 percent Shiite Muslim, about 25 to 28 percent Sunni Muslim, and 5 percent Druze.33 Information on the sectarian composition of the Lebanese population is drawn from the Ministry of Interior’s voter registration data at the zone level, which serves as a reasonable proxy for the sectarian composition of the population.34 The district of voter registration, which is derived from the father’s (or husband’s) district of origin, does not always correspond to place of residence, particularly in the Greater Beirut area. Nonetheless, we can make valid inferences from voter registration for three main reasons. First, electoral demography shapes the behavior of political parties. Second, most Lebanese retain close ties to their villages of origin or, at a minimum, benefit from free transportation provided by political parties during elections. And third, parties operate in urban and rural areas where the same voters reside and are registered to vote. In the case studies, we compare estimates of the actual resident population and the voting population obtained from surveys conducted in Beirut and Mount Lebanon by Statistics Lebanon, a Lebanese research firm.

To unpack the logic of welfare allocation, we rely on qualitative data from in-depth interviews and present parallel case studies of neighborhoods and towns where the Future Movement and Hezbollah either serve out-group members or neglect in-group members. Interviews were conducted with representatives from provider organizations and political parties, officials from relevant government ministries, local development experts and journalists (n=179), and beneficiaries of social welfare programs from the main sectarian groups (n=130). The elite interview protocol focused on organizational background and history, services provided, staff and beneficiary profiles, eligibility criteria, outreach strategies, modes of publicizing services, relationships with state agencies and programs, and possible expansion plans. To gather the most reliable and detailed information from nonelites, Cammett hired and trained a team of six Lebanese graduate students from the main sects, including Christian, Sunni, Shia, and Druze, to conduct in-depth interviews. Each interviewer conducted between fifteen and thirty interviews with coreligionist beneficiaries of social programs, focusing on the types of aid received or sought, organizations that provided support or from which they sought assistance, and political and religious attitudes and behaviors. Interviewees were sampled purposively to maximize variation on key criteria, including gender, age, sect, place of residence, and political preferences. The next section presents the findings from basic statistical analyses of the quantitative data.

Variation in Welfare Outreach, The Future Movement versus Hezbollah: Future Movement and Hezbollah Welfare Provision to In-Group and Out-Group Communities

Conventional wisdom holds that sectarian parties and religious charities largely provide for “their own” while most sectarian parties insist that their service programs serve all, irrespective of sect, and, if anything, focus on poor areas.35

The two organizations undoubtedly focus on lower-income families, but evidence suggests that they target a range of communities and not just the poorest. In the mohafazat of Beirut and Mount Lebanon, the average Future Movement institution is located in a zone that consists of 49 percent upper-middle-class households, 33 percent lower-middle-income households, and only 15.4 percent poor households. This mirrors, though not perfectly, the socioeconomic distribution of the average zone in the region. Hezbollah, too, operates in areas with significant portions of middle-income households, although it serves more poor households than the Hariri Foundation, in part because the Shia tend to be poorer than the Sunnis in the Greater Beirut region. Hezbollah schools, hospitals, and clinics in Beirut and Mount Lebanon are located in areas with about 30 percent upper-middle-income households, 25 percent lower-middle-income households, and almost 39 percent poor households.36 There are, however, many zones in Lebanon with majority poor or lower-middle-income households in which the two parties have not established institutions. When they do target poor areas, the Future Movement and Hezbollah tend to focus on in-group communities.

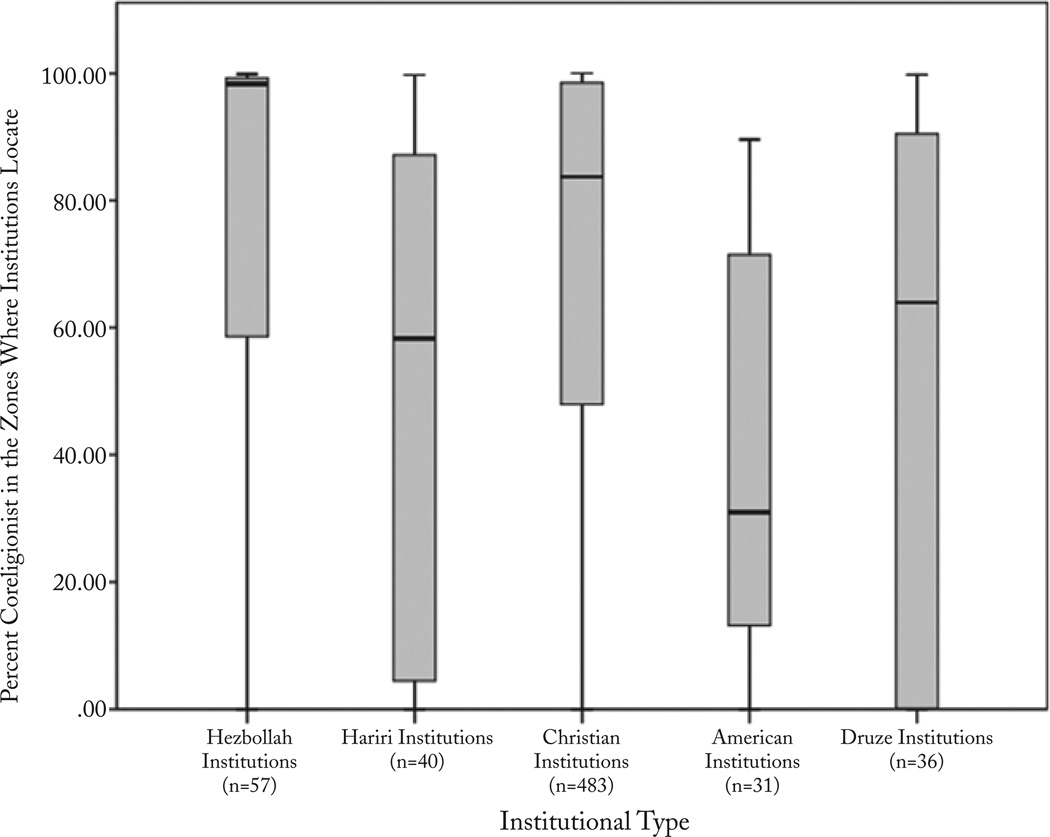

To test the assumption that sectarian welfare institutions provide to “their own,” we descriptively analyze the percentage of in-group members or coreligionists in the zones in which sectarian institutions are located. We link each sectarian institution, the unit of analysis, to zone-level information on sectarian demographics based on the location of the institution. For each institutional type—including the Future Movement and Hezbollah, as well as institutions from the Christian, Armenian, and Druze communities, which are included in our analyses in the “other” category—we aggregate the percentage of coreligionists in the zones where that institution is located. (For example, for the Future Movement, we aggregate the percentage of Sunni for the zones where the affiliated Hariri Foundation has established institutions.) Figure 1 is a box plot of the percentage of coreligionists (Y-axis) by institutional type (X-axis).

Figure 1.

Variation in the Propensity to Target In-Group Communities by Sectarian Welfare Institutions in Lebanon

Sources: Public records at Ministries of Education, Interior, and Public Health; Republic of Lebanon, Daleel al Madaris 2006; interviews with provider organizations by Cammett.

The figure shows that religious and sectarian providers locate in zones with a range of in-group and out-group endowments. Institutions tend to cluster at the upper end of the distribution, which represents provision to in-group communities, but there is sufficient variation in the locational patterns of sectarian and religious providers to question the claim that these organizations merely target their own. At a minimum, the data show that residents from diverse confessional backgrounds inevitably come into contact with—and may even regularly use—services from out-group providers by virtue of the fact that these agencies are located in their neighborhoods or nearby.37

Most important for the questions at hand, the figure shows substantial variation in the propensity to serve out-group members across Hezbollah and Future Movement welfare agencies. More than Future Movement institutions, Hezbollah welfare agencies tend to operate in in-group communities. The median community type, represented by the bar within the boxes, shows that the median Hezbollah institution is located in communities that are more than 98.4 percent Shiite. Because Future Movement welfare agencies target a broader spread of sectarian endowments, the median community type for the party’s agencies is approximately 58.3 percent in-group members.

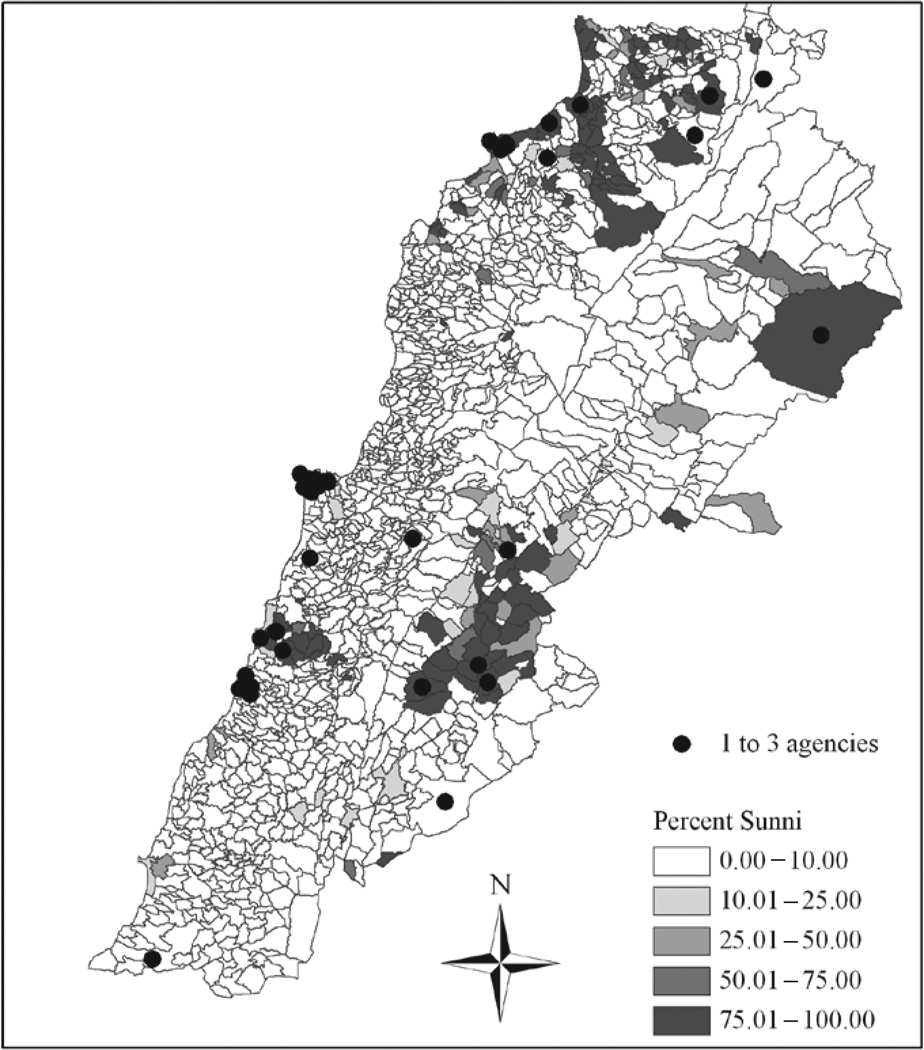

In order to confirm that the above finding is not an artifact of demography, we undertake two further analyses, a detailed descriptive analysis and a multivariate multinomial logit. The demographic distribution of their respective sects may explain why some sectarian providers locate in areas with large concentrations of noncoreligionists. If a sect is relatively dispersed, then welfare institutions targeting these communities are more likely to locate in heterogeneous areas.38 A picture of the overall, national spread of sectarian communities—notwithstanding a tendency toward spatial clustering—shows that most sects occupy a range of demographic positions across the country. (See Figure 2.)

Figure 2.

Demographic Spread by Sect across Zones in Lebanon

Sources: Public records at Ministries of Education, Interior, and Public Health; Republic of Lebanon, Daleel al Madaris 2006; interviews with provider organizations by Cammett.

Figure 2, which uses the zone as the unit of analysis, shows the percentage of each zone that is made up of Shiite and Sunni Muslims as well as other key sects and ethnic groups, including Christians, Druze, and Armenians, throughout Lebanon. Some groups, notably Christians, are dominant in more tracts than others, but most sects, including Shia and Sunnis, are spread across a wide range of demographic proportions in zones across the country. The results therefore suggest that sectarian demographic distributions do not fully explain why Hezbollah and the Future Movement locate in heterogeneous and even noncoreligionist areas. The decidedly nonsectarian rhetoric and efforts of sectarian parties to establish alliances with out-group leaders further suggest that demography does not fully explain the politics of sectarian welfare provision.

We find that Hezbollah locates welfare agencies in zones that are 77 percent Shiite on average, while Future locates its institutions in zones that are 53 percent Sunni on average. The average fractionalization index is 0.15 for zones where Hezbollah locates its institutions and 0.43 percent for zones where Future locates.39 This finding could imply that Future targets zones with higher proportions of out-group members than does Hezbollah. However, we cannot make this interpretation until we control for the unique demographic spread of Shia and Sunni communities in Lebanon. Due to historical contingency, sectarian groups are not randomly spread across Lebanon, nor are they equivalently clustered: Sunnis tend to live in more heterogeneous areas than Shia. For instance, there are 215 zones in the country where Shia make up 90 percent or more of the population, compared with 114 such zones for Sunnis. In order to control for these differences in sectarian endowments, we estimate multinomial logits.40

The dependent variable in our multinomial models is institutional type or, more specifically, the presence of one of three types of institutions among Lebanese zones: Hezbollah welfare institutions, Future welfare institutions, and the welfare institutions of all other sectarian and religious organizations.41 The unit of analysis is thus the sectarian institution. Multinomial logits allow us to directly compare institutions of different types for their propensities to provide to in-group members. The key independent variables are coreligionism and fractionalization of the zones where sectarian institutions locate. Coreligionism is defined as the percentage of the relevant sectarian group in the zone where the institution is located. (Thus, for Hezbollah, coreligionism equals percentage Shia; for the Future Movement, coreligionism equals percentage Sunni, and so on.) Fractionalization is defined as the Herfindahl index of heterogeneity among groups representing the politically relevant42 cleavages in the country (Shia, Sunni, Christian, Druze, Alawi, and Armenian).43

Results from the multinomial logit model suggest that coreligionism does not differentiate between the locations of the three institutional types across space. (See Table 1.) The zones in which the different sectarian institutions locate do not appear to differ on coreligionism, controlling for fractionalization. However, fractionalization does differentiate the location of different institutional types. Zones that are 0.1 higher in fractionalization (which ranges from 0 to 1), are 33.0 percent less likely to have a Hezbollah institution compared with a Future Movement institution, and 26.3 percent less likely to have a Hezbollah institution compared with “other” institutions (Christian, Armenian, or Druze welfare institutions). The Future Movement and other institutions do not differ from each other. In other words, net of coreligionism, Hezbollah appears to have the least propensity to locate in heterogeneous areas compared with either Future Movement or other sectarian and religious institutions. This implies that institutions vary in the way they “respond” to heterogeneity or the existence of the out-group, with the Future Movement establishing welfare agencies in more mixed areas and Hezbollah locating in more homogeneous areas. In the rest of the article we argue that different strategies of political mobilization account for these differences across Hezbollah and the Future Movement.

Table 1.

Multinominal Logit Estimates of the Presence of Different Institutional Typesa

| Betas for Fractionalization | Exponentiated Beta for Fractionalization |

|

|---|---|---|

| Hezbollah-Future Movement | −4.01*** | 0.669 |

| Hezbollah-other | −3.05*** | .0.737 |

| Future Movement-other | 0.962 | — |

p ≤ .1,

p ≤ .05,

p ≤ .01

The table does not show results for the coreligionism variable since this variable does not distinguish among institutional types.

Modes of Political Mobilization and Future Movement versus Hezbollah Welfare Outreach

We argue that different modes of political mobilization explain the varied propensities of the Future Movement and Hezbollah to establish welfare agencies in out-group communities. But this claim begs a prior question, notably why did the two parties adopt distinct forms of mobilization in the first place? We contend that historically contextual factors have shaped the Future Movement’s relative emphasis on electoral politics and Hezbollah’s comparative prioritization of nonelectoral mobilization. Two overarching factors are most germane: first, historical legacies of sectarian representation in the political system, in particular the relative political and economic marginalization of the Shia during the colonial and postcolonial periods; and, second, intrasectarian politics during the civil war and postwar periods that enabled Hariri to dominate Sunni representation by the 1980s but pitted Hezbollah against the Amal Movement in a struggle for domination of Shia politics in the 1980s and 1990s. Long-standing Sunni integration in the Lebanese polity as well as the Future Movement’s relative control over Sunni politics freed the organization to pursue out-group support in the postwar period. Conversely, the history of Shia exclusion and “ethnic outbidding”44 in Shiite politics compelled Hezbollah to prioritize in-group mobilization. Only after it established a dominant position in Shiite politics could Hezbollah turn its attention more seriously to electoral mobilization.

A brief review of the origins and evolution of the Future Movement and Hezbollah traces the two parties’ distinct patterns of political mobilization. While the Future Movement had its roots in the charitable activities of its founder during the civil war and rapidly evolved into a vote-buying political machine in the postwar period, Hezbollah originated as a militia organization that focused on mobilizing heavily Shiite areas during the civil war and spearheading the resistance against Israel.

The Future Movement, led by the former prime minister Rafiq al-Hariri and now headed by his son, Saad al-Hariri, is the dominant political representative of the Sunni community in Lebanon and effectively controls many Sunni charitable institutions.45 Thanks to the relative power vacuum and factionalization within the community during the civil war, as well as a vast fortune made in Saudi Arabia during the 1960s, Hariri gained dominance over political representation of the Sunni sect and progressively established close ties with Sunni religious establishments such as the Maqased and Dar al-Fatwa. During the war he started his charitable initiatives in the predominantly Sunni city of Sidon and later funneled aid to ngos throughout Lebanon, in part to increase his popular appeal.46 In the postwar period Hariri became explicit about his political ambitions. After running in the first postwar elections held in 1992, Hariri was appointed prime minister, a post reserved for a Sunni in Lebanon’s consociational system. Hariri’s monopolization of Sunni institutions and marginalization of potential competitors facilitated his efforts to reach out to non-Sunnis without jeopardizing his standing within his own sect.

The Future Movement initially established its physical institutions in Sunni areas but gradually spread to out-group locations. The Hariri Foundation, which is the charitable wing of the Future Movement, was first established in the predominantly Sunni city of Sidon in 1979 as the Islamic Institute for Culture and Higher Education. The foundation adopted its current name in 1984, when it moved its headquarters to Beirut. In the mid- to late 1980s the Hariri Foundation established several schools in Beirut and Sidon. Until the late 1990s, when it rapidly expanded its health-related activities, it was best known for generous educational scholarships awarded to thousands of students, including non-Sunnis.47 At present, the foundation effectively controls at least one public hospital, the Rafiq al-Hariri Government Hospital in Beirut, and directly runs five primary and secondary schools as well as one university, the Lebanese-Canadian University. In 1999 the Hariri Foundation established the Health Directory, which established over forty clinics, including in out-group areas.48

Hezbollah was established and then evolved under very different conditions than did the Future Movement. Hezbollah emerged in 1982 in response to the protracted Israeli occupation of the South but also for the purpose of organizing the historically marginalized Lebanese Shia community with support from Iran.49 The organization concentrated on serving militia fighters and their families as well as core supporters in the Baalbek region, where it originated, but quickly spread to the South and southern suburbs of Beirut, areas with heavily Shiite resident populations during the war. During the 1980s and early 1990s Hezbollah faced serious competition from the Amal Movement and the Communist Party. Resistance to Israeli occupation and competitive threats from an in-group rival compelled the organization to emphasize its militia activities and Shiite community mobilization. These forms of nonelectoral politics entailed the prioritization of in-group, core supporters over electoral politics, which would have required more explicit attention to out-group communities.

In the postwar period Hezbollah gradually became the dominant representative of the community, as reflected in the party’s ability to drive mass turnout at demonstrations, in its performance in municipal elections, and ultimately in its relative influence in naming candidates for national electoral slates.50 After the war Hezbollah transformed itself into a political party and engaged in more electoral mobilization. 51 The party fielded candidates in selected districts and won seats in all national and municipal elections, while maintaining its military wing to continue the struggle against the Israeli occupation of Lebanese territory. Nonetheless, the party has remained ambivalent about participating in the government and, until 2005, refused to accept cabinet positions. In December 2006 the party pulled its ministers from the cabinet and initiated with its political allies a seventeen-month sit-in in downtown Beirut as an official protest against the distribution of cabinet seats.

Over time Hezbollah established an extensive network of health, educational, public works, and other social centers, starting with medical facilities in the predominantly Shiite Baalbek and in Nabatiyyeh in the South in the mid-1980s and soon after moving into the southern suburbs of Beirut. The bulk of its institutions were established after the war ended in 1990. Although its centers are located almost exclusively in in-group areas, Hezbollah increased its efforts from the 1990s and onward to welcome out-group members, particularly among those residing in the territories it controlled.52 The organization directly operates twenty-four clinics through its Islamic Health Unit, twenty-six schools through its al-Mahdi schools network and associated agencies, four hospitals, a public works and construction wing ( Jihad al-Bina’), a comprehensive social service agency targeting extremely poor families (al-Emdad al-Islamiyya), an agricultural development institution, and other, related organizations. The al-Mustapha schools network, which runs seven primary and secondary schools and was launched by Sheikh Naim Qassem, a member of the Hezbollah politburo, is closely associated with the Hezbollah network. The eligibility criteria of some Hezbollah programs explicitly state that they prioritize fighters and the families of “martyrs,” while representatives of its social programs also openly claim that they target Shia.

In sum, the Future Movement and Hezbollah emerged under different circumstances, leading to distinct strategies of political mobilization. Hariri quickly became the dominant Sunni political leader and gradually, in the 1980s, sought to broaden his appeal, positioning himself to win electoral contests and ultimately to become prime minister in postwar Lebanon. Hezbollah has its roots as an armed resistance group aimed at fighting Israel and mobilizing the Shiite community. In the postwar period the organization gradually embraced electoral politics, but only ambivalently.

Varied emphases on electoral mobilization in the Future Movement and Hezbollah are reflected in their levels of participation in national elections. Data from the 2005 elections is illustrative, particularly because this election cycle was considered much freer than prior postwar elections, which had been controlled by Syria.53 In these elections the Future Movement ran almost twice as many candidates for parliamentary seats as did Hezbollah. More specifically, the Future Movement fielded candidates in twelve out of thirteen qadas with seats reserved for Sunnis while Hezbollah fielded candidates in only seven out of twelve qadas with seats reserved for Shia. In both elections Hezbollah even agreed not to run candidates for some seats as a result of preelectoral bargains with its onetime rival, the Amal Movement, reflecting its ambivalence toward electoral participation. Nonetheless, in the 2005 elections the Future Movement and Hezbollah made a preelectoral bargain, in which they agreed to support each other’s candidates in selected districts, potentially restraining their electoral participation. In the 2009 elections no such bargain was concluded, yet the same general pattern held: the Future Movement fielded candidates in twelve out of thirteen qadas with seats reserved for Sunnis, while Hezbollah ran candidates in just six out of twelve qadas with seats reserved for Shia.

Furthermore, the electoral demography, or the sectarian composition of registered voters, differed in the districts where the two parties chose to field candidates, producing distinct incentives to court out-group voters. In general, the Future Movement tends to field candidates for seats in more heterogeneous districts, whereas Hezbollah tends to field candidates in more homogenous districts. In the 2009 elections Hezbollah fielded candidates in districts that were more homogeneous (with an average fractionalization value of .33) as compared with the districts in which the Future Movement fielded candidates (with an average fractionalization value of .51).54 The Future Movement’s decision to emphasize electoral politics on a broader scale than Hezbollah, then, presents stronger incentives to target out-group communities. The next section provides brief case studies of selected communities in order to trace the ways in which their distinct political strategies have evolved and shaped their social welfare activities in specific localities.

Case Studies: Future Movement and Hezbollah Welfare Outreach and Neglect

For more in-depth analysis, we select communities with varied endowments of coreligionist voters and where the two organizations have and have not established welfare institutions. Figures 3 and 4 depict the locations of Future Movement and Hezbollah welfare agencies, respectively.

Figure 3.

Map of the Location of Future Movement Welfare Agencies and the Distribution of Sunni Muslim Communities in Lebanon

Sources: Public records at Ministries of Education, Interior, and Public Health; Republic of Lebanon, Daleel al Madaris 2006; interviews with provider organizations by Cammett.

Figure 4.

Map of the Location of Hezbollah Welfare Agencies and the Distribution of Shia Muslim Communities in Lebanon

Sources: Public records at Ministries of Education, Interior, and Public Health; Republic of Lebanon, Daleel al Madaris 2006; interviews with provider organizations by Cammett.

The maps shown in the figures indicate that the two parties neglect some areas with high coreligionist concentrations but serve other areas with few in-group members. For example, although Jbeil qada in the north encompasses a string of predominantly Shiite villages, Hezbollah did not seriously target this region until very recently because it was not concerned with contesting elections there. Similarly, in parts of the southern suburbs of Beirut, the Future Movement does not serve Sunni populations because it perceives no electoral utility in doing so. In general, the maps indicate that Hezbollah, more than the Future Movement, tends to neglect areas with low in-group endowments.

Table 2 depicts the communities selected for deeper analysis with the names of corresponding electoral districts listed in parentheses.

Table 2.

Selected Low and High Out-Group Voter Communities with Future Movement and Hezbollah Welfare Agencies

| Low Out-Group Areas | High Out-Group Areas | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Presence of Welfare Institutions |

Hariri Foundation |

Hezbollah | Hariri Foundation |

Hezbollah |

| Yes | many (e.g., Beirut, North, Sidon) | many (e.g., Baalbek-Hermel, South) | Karm al-Zeitoun (Beirut 1) | Southern suburbs/Beirut (Baabda/Aley) |

| No | Ouzai/Shiyah (Baabda) | Shiite villages in Jbeil (Jbeil) | many (e.g., South, southern suburbs/Beirut) | many (e.g., North, Beirut III) |

We focus on two categories of communities, listed in the shaded sections, including areas with high concentrations of coreligionist voters where corresponding organizations do not offer services and places with low concentrations of coreligionists where they have established welfare institutions. It is less surprising that sectarian parties would choose to locate welfare institutions in high coreligionist areas or would neglect low coreligionist areas; we therefore do not focus on these types of communities.

The analysis links each community or zone-level unit to its corresponding electoral district because, as we argue, electoral considerations factor into the decision to serve particular areas over others, albeit in distinct ways across the Future Movement and Hezbollah. We also exploit discrepancies between the sectarian endowments of registered voters and residents in analyzing the dynamics of welfare provision by the two groups. Comparisons of social service provision in urban neighborhoods and rural villages show that the two parties do not target all communities with high concentrations of in-group registered voters and they sometimes serve areas with low in-group electoral endowments. Attention to the larger dynamics of political competition at the electoral district level as well as the differential importance that the two parties attach to contesting elections in these areas helps to explain spatial patterns of social service provision measured at much smaller units of analysis.

Out-Group Communities with Future Movement and Hezbollah Welfare Institutions

The Future Movement in Karm al-Zeitoun, Beirut

In March 2000 the Future Movement established a clinic in Karm al-Zeitoun, a neighborhood in East Beirut with an overwhelmingly Christian population. The clinic is one of six established in the same year, with the largest located in Tariq el-Jedideh, the epicenter of the “Sunni heartland” in West Beirut. All of the organization’s medical facilities are linked through a sophisticated digital medical records system.

In the eyes of some residents, and particularly the administrators of other health centers in the area, this was a surprising if not audacious move. Although high-level staff members claim that it is a nonsectarian, humanitarian organization, the Hariri Foundation is seen as the social service wing of the Hariri family’s political machine, which is viewed as a Sunni institution. East Beirut is historically Christian and includes a large Greek Orthodox community with long-standing roots in the area, as well as Maronites and other Christians, who settled in East Beirut neighborhoods later. The Green Line that separated East and West Beirut during the civil war was considered the dividing line between “Christian” and “Muslim” Beirut. East Beirut’s predominantly Christian character only intensified with the end of the civil war in 1990 and the increased trend toward sectarian homogenization of residential patterns.55

How can we understand the Hariri Foundation’s choice of Karm al-Zeitoun for establishing a medical center? Representatives from the organization insist that socioeconomic need and humanitarianism are the main factors guiding the placement of social institutions.56 These motivations no doubt play a role, particularly on the level of individual staff members and volunteers.57 But if socioeconomic considerations account for macro-organizational decisions about which communities to target with social assistance, it is unclear why the Hariri Foundation selected Karm al-Zeitoun, a neighborhood that is far more prosperous than many other urban and rural areas throughout the country. Furthermore, East Beirut already has a dense concentration of Christian religious charities that aim to meet the basic needs of local residents. Indeed, based on socioeconomic logic, the Hariri Foundation might have diverted its resources away from Beirut to the North, which has become the most deprived part of the country—a region that also has a predominantly Sunni Muslim population.58

Locals interpreted the foundation’s choice of Karm al-Zeitoun as a site for a health clinic as a political move driven by electoral calculations. As the director of a local church-based clinic commented: “It’s all for political reasons…. When elections come, the rates at the clinics go down and food aid increases. Then, little by little, these services disappear until the next electoral period.”59 The timing of the establishment of the Karm al-Zeitoun clinic fits with this account. The clinic was one of five Hariri Foundation health centers established in Beirut between January and July 2000, and a sixth was established in October in Ras Beirut, a neighborhood in West Beirut where the Hariri Family was well established by this time. In 2000 parliamentary elections were held in two rounds, on August 27 and September 3.60 Hariri himself and many Hariri-backed candidates contested the elections in all three Beirut districts, providing an incentive to woo voters from across the city.

In ascribing political motivations for the foundation’s establishment of the Karm al-Zeitoun clinic, it is important to specify the relationship between the neighborhood and the electoral district. Karm al-Zeitoun is located in the First District of Beirut, which at the time included the neighborhoods of Achrafieh (where the clinic is technically located), Mazraa, and Saifi, and allocated two seats to Sunni candidates and four to Christians. Arguably, then, we might interpret the clinic’s establishment as an attempt to shore up support in the Sunni constituencies of the district. Yet, if this were the case, the foundation could have located the center in Mazraa, which encompasses more Sunni voters. In fact, the organization did open a clinic one month earlier, in February 2000, in nearby Ras el Nabaa, which is easily accessed from Mazraa and surrounding areas. Thus, the establishment of the center in Christian Karm al-Zeitoun sent a powerful message that the foundation and, hence, the Hariri family wanted to court non-Sunnis in the electoral district—a message that was not lost on residents. Lebanon’s electoral system creates an incentive for parties to run a full list of candidates for each district, in this case both Sunnis and Christians. Beyond charitable impulses, the establishment of the clinic was a logical move, given Hariri’s emphasis on winning elections and prevailing over in-group and even out-group rivals, and was indicative of his national political aspirations.

Hezbollah in the Southern Suburbs

Hezbollah is well established in the southern suburbs of Beirut, which the media often describe as a “Hezbollah stronghold.” In the area’s four main municipalities, Ghobeiry, Bourj el-Barjneh, Haret Hreik, and Mrayjeh, various organizations run by or affiliated with Hezbollah operate at least four major clinics, the Rasoul el-Azam Hospital, and six schools. A few of these institutions were established in the 1980s and 1990s and, therefore, Hezbollah has a long-standing presence in social service provision in the area—dating back to before the party chose to contest elections in the postwar period.

Given the electoral demography of the southern suburbs, which include the qadas of Baabda and Aley, the high density of Hezbollah institutions—indeed the highest such in all Lebanon—might seem surprising. In Baabda only 23 percent of registered voters are Shia while over 50 percent are Christian, and particularly Maronite Christian, although the district does include two seats reserved for Shia candidates. In Aley, Shia account for only 3 percent of registered voters and no seats are reserved for Shiite candidates, while the vast majority of voters are Druze (53 percent) and Christian (43 percent). Furthermore, interviews with multiple observers—even critics of Hezbollah—attest that the party’s welfare institutions in the southern suburbs do not discriminate in service provision, offering health care at competitive rates to Christians, Sunnis, and Druze patients.61

Why did Hezbollah invest so much in an area where it has relatively little apparent electoral return? The answer to this question begins with Hezbollah’s nonelectoral motivations for service provision, particularly in its early days during the war and the immediate postwar period. From the perspective of nonelectoral mobilization, it was logical to prioritize the southern suburbs, which were home to the largest urban concentration of Shia, population growth spurred by successive waves of migration from Shiite villages in the South and Bekaa from the 1960s onward as well as by the Israeli invasion and occupation of south Lebanon in 1978.62 About a half-million Shia reside in the southern suburbs. Of these about two-thirds had migrated to the area,63 and certain municipalities are overwhelmingly Shiite.64 Thus, in the mid-1980s, when Hezbollah established its first clinics in Haret Hreik and surrounding neighborhoods, a large resident Shiite population was already in place. During the civil war Hezbollah was entirely focused on community mobilization and maintaining its militia to fight Israeli occupation. Thus, Hezbollah’s initial motivations for targeting the southern suburbs were related to nonelectoral politics, including militia competition and community mobilization.

In the postwar period Hezbollah’s political strategies evolved to place increasing emphasis on electoral competition at the municipal and, to a lesser degree, national levels.65 Thus, although the majority of Shiite residents of the southern suburbs are registered to vote elsewhere, welfare outreach also became beneficial for Hezbollah’s electoral prospects.66 Tight linkages between residents of the southern suburbs and their villages and towns of origin as well as party-financed transportation to polling stations throughout the country during electoral cycles ensure that services rendered in Hezbollah-controlled areas in the southern suburbs influence electoral support in predominantly Shiite districts in the South and Bekaa, where Hezbollah fields candidates. Furthermore, Hezbollah serves both residents and voters in the municipalities that it controls, reinforcing its reputation for good governance.67

Different historical moments in Hezbollah’s life cycle are associated with different modes of political mobilization, with electoral ambition increasing in the postwar period. Thus, welfare institutions created under wartime conditions to serve deprived and needy coreligionist communities and maintain a militia force evolved while additional institutions were established in the 1990s onward, in part to support the party’s electoral prospects.

The preceding discussion focuses on communities with significant concentrations of out-group registered voters. For the Future Movement electoral considerations played an obvious role in motivating the creation of the Karm al-Zeitoun clinic in this overwhelming Christian neighborhood of East Beirut. In the case of Hezbollah political goals evolved over time: during the war the establishment of institutions was clearly motivated by community mobilization as well as the need to establish a base for militia operations in areas heavily populated by Shiite residents (but not voters). Although these purposes have not disappeared, electoral considerations gained in importance during the postwar period. The next section examines areas with concentrations of in-group members where the two organizations have not established welfare institutions.

Neglected In-Group Communities

The Future Movement and Sunnis in Ouzai, baabda

Ouzai, a suburb of Beirut located just minutes from upscale, predominantly Sunni areas of West Beirut, is home to a significant Sunni resident population. Indeed, one of the most prominent Sunni religious charities, the Dr. Mohammed Khaled Foundation, is based in the area and boasts a medical clinic, a school, and an orphanage catering to the Sunni community.68 Although parts of the area have luxury housing with seaside views, Ouzai is also home to many low-income families, including a concentration of Sunnis who were displaced from the Qarantina district near downtown Beirut at the outset of the civil war.69 While some displaced Sunnis who came to Ouzai during the war have been resettled or returned to their original homes, many other families remain.

Among the resident Sunnis of Ouzai is a core group of Future Movement activists who prominently display photos of the Hariri family. During street clashes in May 2008, opposition forces even targeted the homes of Future Movement supporters in the area.70 Yet Sunni families complain that the Future Movement generally neglects the area. In an interview in December 2007, a woman from a displaced Sunni family in Ouzai commented:

[A]ll the mps of Beirut enter this house [during electoral campaigns], without exception…. They did nothing for me…. My goal was that one day when my children grow up, they can be employed…. When it comes to us, they know us only during elections. During elections, they send for us, and they welcome us, and they also welcome us during the caucuses in order to fill the seats…. We came here for only a week or more, we have been here for 32 years. Imagine, in the summer you find fire, in the winter you find flooding. When it rains, water enters the homes of the people and the sea rises and enters the homes of the people. The parliamentarians come to see the misery and the situation. They come, make video clips and they leave. Did Sheikh Rafiq [Hariri] do anything for Dahiyeh? From the Summerland to Ouzai, we put up pictures and banners for the ministers and the mps [of the Future Movement]; after the elections, we do not see anyone.71

Although Sunni residents of Ouzai are active supporters of the Future Movement and even volunteer for the party during electoral campaigns, their requests for social assistance from the organization went unheeded. For example, the interviewee noted that local supporters unsuccessfully appealed to the Future Movement to construct a health clinic in the area, arguing that a medical center would signal real commitment to Sunnis in Ouzai, whereas the periodic distribution of money and foodstuffs during holidays and electoral campaigns would be less effective. As a result of the party’s neglect, the interviewee claimed that its popularity has decreased among Sunnis in the area: “Hariri and his bloc are losing popularity here. Their pictures are being ripped down. My husband was afraid we would reach this point, and he told them that opening a clinic is more important than disbursing money.”72

What explains the Future Movement’s relative neglect of Ouzai despite its generosity in other parts of Greater Beirut, including neighborhoods with and without significant concentrations of Sunnis? Residents interpret the organization’s neglect of Ouzai as an electoral calculation. The Future Movement has little incentive to invest in the area because it is located in a district where the organization does not seriously contest elections: the neighborhood falls in the Baabda voting district, an area dominated by Hezbollah. Even though Baabda hosts pockets of Sunnis residing in its neighborhoods, Sunnis account for only 6 percent of registered voters in the district. Although a Future Movement candidate, Bassem Sabeh, won a Shiite seat in the 2005 elections, his successful bid was the result of a temporary preelectoral alliance between the Future Movement, Hezbollah, and other parties, which established joint lists of candidates in certain districts. This marriage of convenience, which did not reflect a commitment to shared principles or goals, essentially predetermined the election results.73 In the more competitive 2009 elections, where no such arrangement was established, Sabeh was defeated while Hezbollah candidates won both Shia seats in the district. The Future Movement has poor prospects in Baabda and other Hezbollah-dominated districts and therefore does not funnel resources into these areas, whether to entice voters or to reward existing supporters. In the next section we turn to Hezbollah’s inattention in Shia communities in parts of Lebanon.

Hezbollah and the Shiite Villages of Jbeil

Beyond the South and Bekaa, where the preponderance of Shiite communities are located, substantial pockets of Shia reside in Jbeil, where Shia account for 19 percent of registered voters. A group of about ten villages in the central and upper mountainous regions of Jbeil, including Qarqouraya, Bazioun, Afqa, Frat, Aalmat, Hjoula, Ras Osta, Lassa, and others, constitute a “Shiite belt” in Jbeil. The civil war led to Shiite migration from these villages, partly to the southern suburbs of Beirut and other areas outside of Jbeil. Many Shia also migrated to Amsheet, a coastal town in Jbeil, and specifically to the Kfar Saleh neighborhood, which grew rapidly during the war.74 The district includes one seat reserved for a Shiite candidate, providing an electoral incentive to distribute benefits to Jbeil’s resident Shia.

When the civil war ended in 1990, Hezbollah made some efforts to reach out to the Shia of Jbeil but did not prioritize the area. The organization began with informal discussion-study circles (durus diniyya), when party clerics would visit the qada and meet with local men to increase their religious consciousness. In the immediate postwar period Hezbollah also established some social institutions in the area, notably al-Mu’assasa al-Khayriyya al-Islamiyaa li-Abna’ Jbeil-Kesrouan, and occasionally arranged for road paving but did not make a concerted effort to cultivate support among the Shia of Jbeil.75 Other Shiite organizations also operated in the area, including the charity of Sayyid Muhammad Husayn Fadlallah, a prominent Shiite leader in Lebanon with a global following, and the Amal Movement. Hezbollah made no effort to compete with these groups or to step up its activities in Jbeil.76 An interview with a Christian woman from Jbeil confirmed Hezbollah’s decision to limit the scale of its operations in the district. When the woman visited a party office in Haret Hreik in the Beirut southern suburbs to request social assistance, a Hezbollah official informed her that the party “does not work in her region.”77 Located outside of Hezbollah’s main territorial bases where much larger concentrations of Shia reside, Jbeil was not a priority for Hezbollah, particularly given the party’s focus on nonelectoral mobilization.

In the run-up to the 2005 elections and particularly afterward, Hezbollah more actively targeted Jbeil with social benefits. In 2004 al-Haya’a al-Suhiyya, Hezbollah’s health organization, established a clinic in Amsheet, a predominantly Christian village with a significant emigrant community of Shia from the Shia mountainous villages. Hezbollah also obtained permits to establish seven additional clinics and is in the process of launching two of them in Amsheet and Mishan. After Iran sent extensive resources to Hezbollah in the wake of the 2006 Israeli-Lebanese War, the party distributed material aid to residents of Jbeil and poured money into infrastructure, which locals refer to as “Iranian asphalt.” Longtime politicians in Jbeil as well as independent analysts with contacts in Hezbollah claim that the party has decisively stepped up its social and political outreach in Jbeil since 2005.78

Hezbollah’s revised stance toward Jbeil from roughly 2005 onward is directly related to its decision to engage more fully in electoral politics, a move partly shaped by shifting national political dynamics. The Syrian withdrawal in March and April 2005 meant that national elections held several months later were freer than prior rounds, introducing more uncertainty into the outcomes. Although Hezbollah participated in a preelectoral bargain with Hariri, the Druze Popular Socialist Party (psp), and the Amal Movement against Michel Aoun’s Free Patriotic Movement (fpm), observers from different political affiliations claim that the party’s endorsement of the alliance’s candidate for the Shiite seat was mixed. In the end the incumbent, ‘Abbas Hashem, who ran as an open supporter of the fpm against the alliance, held the seat.79

After the 2005 elections Hezbollah made additional efforts to cater to the Shia of Jbeil. Electoral considerations were clearly at play. First, the 2008 election law separated Jbeil and the almost purely Christian qada of Kesserouane into two electoral districts, thereby increasing the weight of the Shiite vote in Jbeil. Second, the party’s 2006 alliance with the fpm, which faced competition from other Christian parties, called for Hezbollah to mobilize Shiite voters in support of its ally. The consolidation of the Shiite vote over time points to Hezbollah’s increasing efforts to engage in electoral politics in the qada. In 2000 Shiite votes in Jbeil were divided across five lists, with no outright majority for any slate. In 2005 Shiite votes were divided across three lists, again with no majority and relatively close percentages won by each slate. In 2009, 89 percent of Shiite voters cast their ballots for the Hezbollah-backed fpm candidate, and their turnout—approximately 68 percent—was the highest of all postwar elections in the qada. Before the 2009 elections Hezbollah did not exert much effort to influence voter choices or, as in 2005, sent out mixed messages to in-group voters. In 2009, however, after a concerted burst of post-2005 Hezbollah attention to the area, including increased service provision, the Shia of Jbeil suddenly evolved into a tight voting bloc analogous to the Shia of Baabda in the southern suburbs.80

As these accounts of the relative neglect of Ouzai and Jbeil in specific periods suggest, political factors also shape nonoutreach to in-group communities. In some neighborhoods and villages with high densities of in-group members, the Future Movement and Hezbollah have refrained from establishing welfare institutions or limited the distribution of social benefits. For the Future Movement, the decision not to invest in Ouzai was shaped by electoral incentives, while the prioritization of nonelectoral over electoral politics explained Hezbollah’s initial neglect of Jbeil.

Conclusion

The establishment of bricks and mortar welfare agencies provides a window onto the political mobilization strategies of sectarian parties. We argue that the degree to which sectarian parties cater to members of out-groups reflects the types of political mobilization they prioritize. In polities where the basic rules of the game are contested, sectarian parties may engage in both electoral and nonelectoral politics, and different types of mobilization, including contesting elections, organizing public protests, and engaging in militia warfare, imply distinct patterns of distributing welfare goods. When parties prioritize winning votes, they are most likely to distribute services broadly, even across sectarian lines, while nonelectoral mobilization implies that core, in-group activists receive particularly generous and continuous welfare benefits. The predominantly Sunni Future Movement’s long-standing emphasis on vote buying helps to explain its more extensive targeting of out-group communities, while the Shiite Hezbollah, which began as a wartime militia and has been far more ambivalent toward electoral politics, has historically favored high-density Shiite areas.

Based on case studies of political organizations in Lebanon, these findings invite further exploration both within and beyond Lebanon. First, future analyses should explore the dynamics of social provision in other sectarian communities in Lebanon, such as the Christian community, where competition over representation is more heated. Conceivably, greater fragmentation within the sect increases ethnic outbidding threats from rivals and compels an organization to woo in-group members most fervently. Second, comparisons of the distributional patterns of other welfare goods such as food packages would illuminate the varied distributive dynamics behind more mobile, short-term forms of clientelism and more fixed, bricks and mortar clientelism. Third, comparisons with ethnic and religious nonstate providers in other developing countries would test the generalizability of our claims. For example, the Sadrist Movement and Kurdish groups in Iraq, Hamas in Palestine, the Hindu Bharatiya Janata Party (bjp) in India, and the Tamil Tigers in Sri Lanka all provide social services that have helped to further both their electoral and their nonelectoral political goals.

Finally, the determinants of electoral versus nonelectoral mobilization deserve further analysis. For example, three factors may be central to a broader theory of the conditions under which ethnic or sectarian parties favor electoral over nonelectoral strategies, including military defeat, intragroup dominance by a single party, and in-group advancement. When an organization concedes military defeat, it may have no choice but to adopt a more mainstream, electoral approach to political mobilization—or at least to shed its antisystem approach. The official abandonment of a military strategy by the Shiite Sadrist Movement—its shift toward “social” and electoral mobilization following defeat by Iraqi government and U.S. forces in Baghdad and southern Iraq in 2008—supports this logic. Control over in-group politics by a single organization may also increase the likelihood of a move toward electoral mobilization. The Future Movement’s relatively early adoption of an electoral strategy was facilitated by the virtual power vacuum within the Lebanese Sunni community. As the dominant representative of the community, the party could afford to court out-group members without alienating its in-group base or risking defection by in-group supporters to competitors. In addition, in-group status advancement may free parties to look beyond their own communities. If perceptions of the relative deprivation of the in-group vis-à-vis other groups dissipate, then parties and their nonparty affiliates can seek support from out-group members without incurring blame for neglecting the needs of their base communities. Depending on context, these three factors— military defeat, party dominance, and in-group advancement—may operate independently or may interact to drive a shift from nonelectoral to electoral strategies of party mobilization.

Social welfare provision by sectarian parties has implications for debates about the “moderation” of politico-religious movements as well as redistribution in plural societies. First, a growing body of research suggests that participation in mainstream political channels, including but not limited to elections and state institutions, breeds moderation of “extremist” organizations.81 To the degree that contesting elections entails courting out-group members, which is in part contingent on districting and electoral rules, then this research supports this argument. Of course, the decision to participate in elections in the first place is a strategic choice that in and of itself should be examined. Second, this research speaks to emerging research on the consequences of nonstate social welfare. In Lebanon and many other developing countries where state institutions are underdeveloped or virtually absent, ethnic or sectarian organizations—including those with political aspirations— provide much-needed social services. But the politicization of service provision by these providers can lead to uneven coverage or inequalities that further entrench societal divisions and can even be a matter of life and death if access to care is contingent on ascribed identity or political allegiances.

Footnotes

For helpful comments on earlier drafts, we thank Mona El-Ghobashy, Wendy Pearlman, Jonah Schulhofer-Wohl, and participants at the Middle East Workshop at Harvard, the Colloquium on Comparative Research at Brown, and the Seminar on Religion and Politics at Yale. We also thank four anonymous reviewers for their comments and suggestions. You-Rim Bak, Marlin Dick, Salwa Maalouf, Lina Mikdashi, and Zina Sawaf provided excellent research assistance. All errors are our own. Correspondence should be directed to Melani Cammett (Melani_Cammett@Brown.edu), who gratefully acknowledges support for this research from the Smith Richardson Foundation, the U.S. Institute of Peace, the Academy Scholars Program at Harvard University, and the Solomon Faculty Research Grant from Brown University.

In plural societies, as opposed to societies with diverse cultural communities, ethnicity, religion, or other types of identity-based cleavages are politically salient and communities are politically organized; Rabushka and Shepsle 2009 [1972], 62.

Alesina, Baqir, and Easterly 1999; Habyarimana, Humphreys, Posner, and Weinstein 2007; Lieberman 2003; Miguel 2003; Tsai 2007.