Abstract

The IGF pathway has been implicated in the regulation of neuroendocrine tumor (NET) growth, and preliminary studies suggested that ganitumab (AMG 479), a human MAB against IGF1R, may have antitumor activity in this setting. We performed a two-cohort phase II study of ganitumab in patients with metastatic progressive carcinoid or pancreatic NETs (pNETs). This open-label study enrolled patients (≥18 years) with metastatic low- and intermediate-grade carcinoid or pNETs. Inclusion criteria included evidence of progressive disease (by Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors (RECIST)) within 12 months of enrollment, ECOG PS 0–2, and fasting blood sugar <160 mg/dl. Prior treatments were allowed and concurrent somatostatin analog therapy was permitted. The primary endpoint was objective response. Secondary endpoints included overall survival (OS), progression-free survival (PFS), and safety. Sixty patients (30 carcinoid and 30 pNETs) were treated with ganitumab 18 mg/kg every 3 weeks, among whom 54 patients were evaluable for survival and 53 patients for response. There were no objective responders by RECIST. The median PFS duration was 6.3 months (95% CI, 4.2–12.6) for the entire cohort; 10.5 months for carcinoid patients, and 4.2 months for pNET patients. The OS rate at 12 months was 66% (95% CI, 52–77%) for the entire cohort. The median OS has not been reached. Grade 3/4 AEs were rare and consisted of hyperglycemia (4%), neutropenia (4%), thrombocytopenia (4%), and infusion reaction (1%). Although well tolerated, treatment with single-agent ganitumab failed to result in significant tumor responses among patients with metastatic well-differentiated carcinoid or pNET.

Keywords: neuroendocrine tumors, carcinoid

Introduction

Neuroendocrine tumors (NETs) comprise a heterogeneous spectrum of neoplasms. NETs are commonly subclassified into two broad subgroups according to their site of origin: pancreatic NETs (pNETs) are thought to arise from the endocrine cells of the pancreas, whereas NETs of other sites such as the lungs or gastrointestinal tract are often referred to as carcinoid tumors (Kulke et al. 2012). NETs can be further classified according to histological subtype. A recent classification system divides NETs into well-differentiated tumors (comprising tumors of low or intermediate grade) or the more aggressive poorly differentiated high-grade tumors (Klimstra et al. 2010).

Treatment options for metastatic, well-differentiated NETs have expanded in recent years. NETs may have the ability to secrete hormones, biogenic amines, and other vasoactive substances that can give rise to diverse clinical syndromes, including flushing and diarrhea. The somatostatin analogs (SSAs) octreotide and lanreotide were initially developed to palliate such hormonal symptoms (Kvols et al. 1986). Recently, a randomized phase III trial of octreotide long-acting repeatable (LAR) in patients with metastatic midgut carcinoid tumors demonstrated a significant improvement in time-to-progression, thereby expanding SSA use to carcinoid tumor patients who do not have symptoms of hormonal hypersecretion (Rinke et al. 2009). pNETs appear to be sensitive to cytotoxic alkylating agents, including streptozocin (Moertel et al. 1992, Kouvaraki et al. 2004) or temozolomide-based regimens (Kulke et al. 2006, Strosberg et al. 2011). Additionally, treatment with the mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) inhibitor everolimus or the small molecular tyrosine kinase inhibitor (TKI) sunitinib was recently shown to prolong progression-free survival (PFS) among patients with advanced pNET (Raymond et al. 2011, Yao et al. 2011). However, objective tumor responses associated with these targeted agents are uncommon and were reported to be below 10% in phase III trials.

Despite these recent advances, there remains a clear need for additional systemic agents with antitumor activity. Accumulating evidence demonstrates that gastrointestinal NETs over-express the circulating ligands insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF1) and IGF2 as well as their receptors (IGFRs; Wulbrand et al. 2000). Moreover, the primary downstream phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K)/AKT/mTOR signaling pathway is known to be dysregulated in a high proportion of NETs (Jiao et al. 2011). Preclinical studies in carcinoid cell lines demonstrate that IGF1 is a major autocrine regulator of neuroendocrine secretion and growth, a process that is mediated through the PI3K/AKT pathway (von Wichert et al. 2000). Immunoneutralization of endogenously released IGF1 markedly reduces basal chromogranin A (CgA) release. Additional preclinical studies of an IGF1R inhibiting TKI in carcinoid and insulinoma cell lines have demonstrated cell cycle arrest at the G1/S checkpoint as well as induction of apoptosis via activation of caspase-3 (Hopfner et al. 2006).

Ganitumab (AMG 479) is a fully human MAB (IgG1) directed against IGF1R. Ganitumab inhibits the interaction of IGF1R with its natural ligands, IGF1 and IGF2. Blockade of IGF1R signaling by ganitumab has been found to inhibit activation of the PI3 kinase/AKT pathway, leading to growth inhibition in preclinical tumor models of pancreatic adenocarcinoma (Beltran et al. 2009). Ganitumab treatment in these models also results in a persistent and substantial reduction of IGF1R concentrations that is probably caused by increased receptor internalization and decay. Preclinical testing has shown that ganitumab does not bind to the closely related insulin receptor (INSR) or interfere with insulin binding to INSR homodimers in vitro (Beltran et al. 2009).

In a dose-escalation phase I clinical trial of ganitumab, one partial response and one minor response was observed among five NET patients who enrolled in the study (Tolcher et al. 2009). The patient who achieved the partial response remained on trial for 21 months and the patient who experienced the minor response continued on study for over 27 months. To more definitively assess the potential activity of ganitumab in patients with NET, we performed a multicenter, two-cohort, single-arm phase II study enrolling patients with advanced carcinoid or pNETs. Patients were treated with ganitumab 18 mg/kg i.v. every 3 weeks and were followed for evidence of tumor response, safety, and survival.

Patients and methods

Patient selection

This study was an open-label, single-arm, two-cohort (carcinoid and pNET) phase II prospective clinical trial. The protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board at each participating center, and the study was conducted in accordance with Good Clinical Practice principles. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Subjects were adults (age ≥18 years) with locally advanced or metastatic well-differentiated (low or intermediate grade) carcinoid or pNETs. Patients without clinical evidence of a pancreatic primary site were considered to have carcinoid tumors. Patients were required to have evidence of progressive disease by Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors (RECIST) within 12 months of study entry. Any number of prior treatments were allowed, and concurrent therapy with SSAs was permitted as long as patients remained on a stable dose. Other key eligibility criteria were measurable disease, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status ≤2, absolute neutrophil count ≥1500 cells/μl, platelets ≥100 000 cells/μl, total bilirubin ≤2.0 mg/dl, AST and ALT ≤2.5×upper limit of normal, and creatinine ≤2.0 mg/dl. Patients with diabetes were eligible as long as fasting blood glucose was <160 mg/dl and HbA1c was <8%. Key exclusion criteria included poorly differentiated histology, insulin-secreting tumors (insulinomas), and myocardial infarction within 6 months.

Treatment and evaluation

Ganitumab was administered i.v. at a dose of 18 mg/kg over 60 min every 3 weeks. A single 50% dose reduction was allowed for grade ≥3 thrombocytopenia. Drug was held for grade ≥3 hyperglycemia and resumed at full dose after appropriate medical management. All other grade 4 non-hematological events considered related to ganitumab led to removal of patients from the study protocol. Evaluation visits were scheduled every 3 weeks along with standard blood tests (complete blood count, comprehensive metabolic panel). Tumor markers (e.g. CgA) and other secretory proteins or amines (e.g. 5-hydroxyindoleacetic acid) were monitored every 9 weeks, if elevated at baseline. Radiological assessments of tumor burden (multiphasic computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scans) were scheduled every 9 weeks. RECIST version 1.0 was used for evaluation of the primary endpoint.

Sample size calculation

The primary end point was the objective radiographic response rate. Secondary end points included PFS, overall survival (OS), and toxicity, calculated according to the NCI Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events version 4.0 (CTCAEv4.0). The sample size calculation was based on the assumption that a true response rate of greater than 16% (comparable with that seen with agents such as sunitinib in pNET (Raymond et al. 2011) or bevacizumab in carcinoid tumors; Yao et al. 2008) would generate interest in a larger randomized study, whereas a true response rate of less than 5% would not yield further interest in this agent. Taking into account both study feasibility given these relatively rare tumors and the relatively small difference in H1 and H0, we designed to study to enroll 30 patients in each cohort, with a type 1 error of 6% and a power of 73%. Under this model, three or more responses in either cohort would have suggested that ganitumab is active.

Statistical analysis

The Kaplan–Meier method was used to estimate all time-to-event functions. PFS was defined as the time from start of treatment until disease progression or death as a result of any cause. OS was defined as the time from start of treatment until death as a result of any cause, with patients censored at the date of last follow-up if still alive. All tests were two sided and statistical significance was declared at P<0.05. Statistical analysis was performed using STATA IC (Stata Statistical Software, Release 10.0; Strata Corp., College Station, TX, USA).

Results

Patient population

A total of 60 patients were enrolled in two cohorts: 30 carcinoid tumors and 30 pNETs (Table 1). The median age of the patient population was 61 years; there was a preponderance of females (n=38) compared with males (n=22). The great majority (56/60) had a performance status of 0 or 1, and more than half (n=34) received concurrent octreotide. Twenty patients had hormonally functioning tumors, including 17 patients with carcinoid syndrome. Among patients with pNETs, two had gastrinomas and one had a glucagonoma; the remainder were hormonally nonfunctioning.

Table 1.

Patient demographics and clinical characteristics.

| Characteristic

|

n

|

%

|

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Male | 22 | 37 |

| Female | 38 | 63 |

| Age (years) | ||

| Median | 61 | |

| Range | 30–82 | |

| Race | ||

| White | 52 | 88 |

| Black or African ancestry | 5 | 8 |

| Hispanic | 2 | 4 |

| Performance status | ||

| 0 | 19 | 32 |

| 1 | 37 | 62 |

| 2 | 4 | 7 |

| Diagnosis | ||

| Carcinoid | 30 | 50 |

| pNET | 30 | 50 |

| Elevated baseline chromogrinin A | ||

| No | 10 | 17 |

| Yes | 48 | 80 |

| Unknown | 2 | 3 |

| Baseline chromogrinin A | ||

| Median | 474 | |

| Range | 2–72 400 | |

| Primary site | ||

| Small bowel | 20 | 33 |

| Pancreas | 30 | 50 |

| Rectal | 1 | 2 |

| Lung | 6 | 10 |

| Gastric | 1 | 2 |

| Unknown | 2 | 3 |

| Grade | ||

| Low | 53 | 88 |

| Intermediate | 5 | 8 |

| Unspecified | 2 | 3 |

| Concurrent sandostatin | ||

| No | 26 | 43 |

| Yes | 34 | 57 |

| Prior lines of therapy | ||

| Median | 2 | |

| Range | 0–9 | |

| Octreoscan positivity | ||

| No | 9 | 15 |

| Yes | 36 | 40 |

| Unspecified | 15 | 25 |

Most patients were heavily pretreated: 44 had received prior cytotoxic chemotherapy (including temozolomide, capecitabine, 5-fluorouracil, dacarbazine, and streptozocin), 35 received prior octreotide, 28 received prior everolimus, 15 had prior bevacizumab, five had prior sunitinib, and six had prior interferon α. After enrollment on the clinical trial, 34 patients remained on octreotide LAR whereas 26 patients did not receive concurrent SSA therapy.

Duration of therapy

Patients received a median of six treatment cycles. Reasons for discontinuation included radiographic tumor progression (n=29), symptomatic progression (n=10), physician decision (n=5), withdrawal of consent (n=5), toxicity (n=3) death on study (n=2), and prolonged treatment delay (n=1). Five patients required a single-dose reduction, due to neutropenia (n=2), thrombocytopenia (n=2), and hyperglycemia (n=1). Toxicities leading to treatment discontinuation included hypersensitivity reaction (n=1), hyperglycemia (n=1), and colitis (n=1).

Safety

Ganitumab was well tolerated with only 54 moderate (grade 2), 27 severe (grade 3), and four life-threatening (grade 4) adverse events (AEs) that were considered at least possibly related to treatment (Table 2). Among these, only five grade 3 and two grade 4 toxicities were considered likely related to treatment including hyperglycemia (4%), neutropenia (4%), thrombocytopenia (4%), and infusion reaction (1%). The most common AEs overall were hyperglycemia (n=27), nausea (n=15), thrombocytopenia (n=14), and infusion-related reaction (n=11).

Table 2.

Treatment-related toxicity.

|

|

Grade 1

|

Grade 2

|

Grade 3

|

Grade 4

|

Total

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hematological toxicity | |||||

| Anemia | 8 | 7 | 1 | 0 | 16 |

| Lymphopenia | 3 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 10 |

| Neutropenia | 2 | 3 | 2 | 0 | 7 |

| Thrombocytopenia | 11 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 14 |

| Non-hematological toxicity | |||||

| Abdominal pain | 4 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 6 |

| Elevated ALT | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 |

| Elevated alkaline phosphatase | 6 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 9 |

| Anorexia | 7 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 9 |

| Arthralgia | 2 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 3 |

| Elevated AST | 7 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 9 |

| Chills | 7 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 8 |

| Constipation | 4 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 5 |

| Dehydration | 3 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 5 |

| Diarrhea | 5 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 7 |

| Fatigue | 22 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 27 |

| Fever | 5 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 7 |

| Headache | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 |

| Hyperglycemia | 7 | 11 | 8 | 1 | 27 |

| Hyperkalemia | 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 5 |

| Hypocalcemia | 5 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 6 |

| Hyponatremia | 6 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 7 |

| Infusion-related reaction | 4 | 6 | 0 | 1 | 11 |

| Infection | 0 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 3 |

| Myalgia | 3 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 5 |

| Nausea | 14 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 15 |

| Maculopapular rash | 3 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 5 |

| Vomiting | 4 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 5 |

| Weight loss | 3 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 4 |

| Total | 158 | 54 | 27 | 4 | 243 |

Immunogenicity

A total of 58 subjects had a baseline sample available and three of them tested positive for anti-AMG 479 binding antibodies but negative for neutralizing antibodies. A total of 52 subjects had at least one post-dose sample available and none tested positive for antibodies against AMG 479 post-dosing.

Radiological and biochemical response

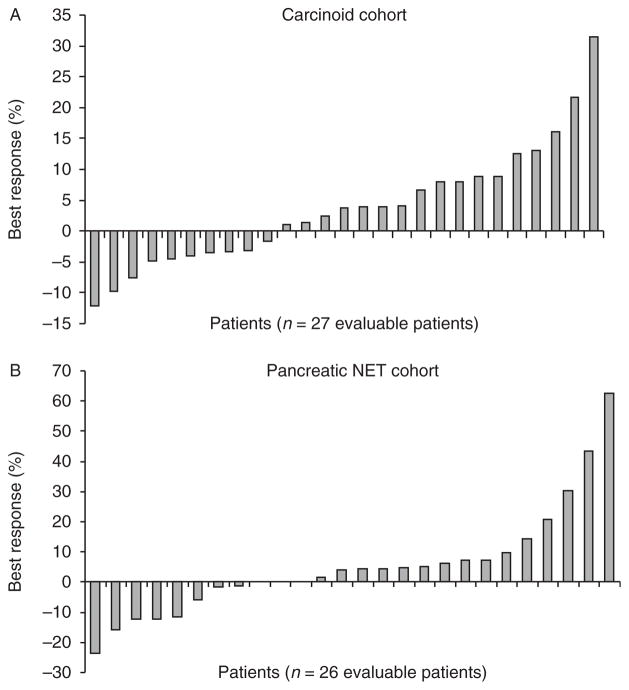

Fifty-three patients were evaluable for response. Seven patients withdrew from the study before radiographic evaluation due to symptomatic deterioration (n=2), patient choice (n=2), physician decision (n=2), and a hypersensitivity reaction to the trial drug (n=1). There were no objective radiological responders by RECIST. When best response to therapy was evaluated, 37% (10/27) evaluable carcinoid patients and 31% (8/26) evaluable pNET patients appeared to have experienced some degree of tumor shrinkage, while 63% (17/27) of the carcinoid patients and 58% (15/26) of the pNET patients appeared to experience continued tumor growth (Fig. 1). Among 38 patients who had baseline elevated serum CgA levels, four patients (11%) experienced major reductions (>50%) or normalization of tumor marker levels. An insufficient number of patients had baseline elevations of 5HIAA to draw meaningful conclusions regarding 5HIAA response; a formal assessment of symptomatic response was not performed as part of this study.

Figure 1.

Waterfall plot illustrating best radiographic response (percent change) in each patient stratified by tumor cohort. (A) Maximum percentage of reduction in sum of tumor diameters from baseline (carcinoid tumor cohort). (B) Maximum percentage of reduction in sum of tumor diameters from baseline (pancreatic NET cohort).

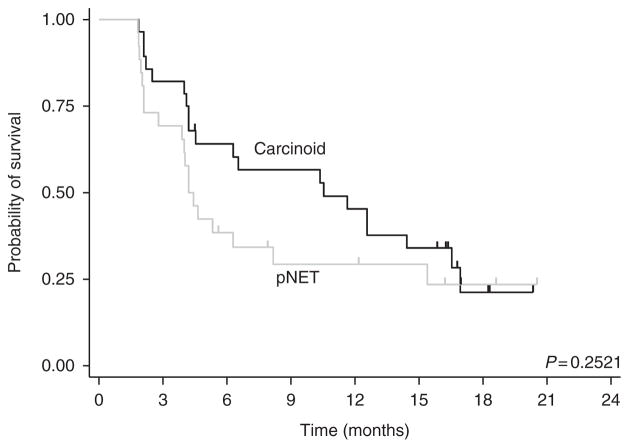

PFS and OS

Fifty-four patients (28 carcinoid and 26 pNETs) were evaluable for PFS and all 60 patients were evaluated for OS. At the time of data cutoff, 19 patients had died and 34 were alive, with follow-up duration for the surviving patients ranging from 2 to 20 months. The overall median PFS was 6.3 months (95% CI, 4.2–12.6 months). Stratified by tumor group (Fig. 2), the median PFS of patients with carcinoid tumors and pNETs was 10.5 months (95% CI, 4.2–16.5 months) and 4.2 months (95% CI, 2.8–8.2 months) respectively.

Figure 2.

Kaplan–Meier estimate of progression-free survival stratified by tumor cohort.

Thirty-four patients on the trial continued prior treatment with octreotide LAR after initiation of ganitumab, whereas 26 patients did not receive concurrent octreotide. The median PFS among the combination cohort was 14.4 months compared with only 4.1 months among patients who did not receive concurrent octreotide (P=0.0001).

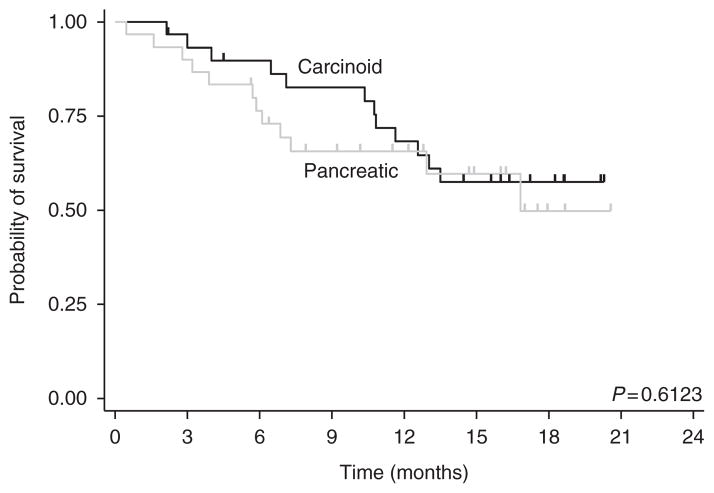

Median OS has not been reached. The 12-month OS rate was 66% (95% CI, 52–77%) and the 18-month OS rate was 53% (95% CI, 37–67%). Stratified by tumor group (Fig. 3), the 1-year survival-rate of patients with carcinoid and pNETs was 68% (95% CI, 48–82%) and 65% (95% CI, 45–80%) respectively.

Figure 3.

Kaplan–Meier estimate of overall survival, stratified by tumor cohort.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this trial represented the largest study of an IGF1R inhibitor in patients with advanced NET. Preclinical data suggested that the IGF1R signaling transduction pathway may be constitutively activated in NETs and that inhibition of the IGF1R could therefore alter the natural history of disease. However, our study failed to demonstrate significant clinical activity associated with ganitumab in patients with either carcinoid or pNETs.

As in prior phase II studies performed with ganitumab in other indications, treatment was associated with relatively little toxicity. Grade 3 and 4 events were uncommon and included thrombocytopenia, neutropenia, and hyperglycemia. A similar pattern of toxicity was observed in a phase II study of ganitumab in 38 patients with Ewings sarcoma; these toxicities were also reported in a randomized phase II study of gemcitabine with or without ganitumab in patients with advanced pancreatic cancer (Kindler et al. 2012). Treatment-associated toxicity led to treatment discontinuation in only three of the 60 patients enrolled in our study.

Despite the good tolerance of the drug, however, we failed to observe significant evidence of antitumor activity. As in several earlier studies of NETs (Kulke et al. 2008, Yao et al. 2010), we used a single-arm phase II design with response rate as the primary endpoint; none of the 60 patients enrolled experienced a partial response. Single-arm phase II studies in NET, particularly those investigating targeted agents, have recently been criticized due to the fact that treatment with many novel agents may result in tumor stabilization rather than significant tumor shrinkage, which may not be appreciated with a single-arm design (Kulke et al. 2011). Indeed, in randomized studies of patients with advanced pNET, responses associated with everolimus or sunitinib were uncommon, yet both drugs significantly improved PFS.

To address this potential limitation and to assess whether ganitumab may have resulted in lesser degrees of tumor shrinkage than measured by RECIST, or in tumor stabilization, we investigated responses using a waterfall plot analysis. In contrast to parallel results in prior phase II studies of everolimus or sunitinib, in which a majority of treated patients had either stable disease or experienced at least some decrease in tumor burden as their best response to therapy, the majority of both carcinoid and pNET patients in our study experienced progressive disease as their best response. We additionally compared PFS in our study with values obtained in other studies to assess whether ganitumab had potential activity in NET. Such historical comparisons can be limited by selection bias and the use of different eligibility criteria in different trials. We attempted to minimize inter-trial variability by requiring progression within 12 months of study entry, a requirement that paralleled the entry criteria for placebo-controlled randomized studies of everolimus and sunitinib in pNET, as well as the entry criteria for a recent placebo-controlled randomized study of everolimus in patients with advanced carcinoid tumors (Pavel et al. 2011, Raymond et al. 2011, Yao et al. 2011). The PFS time of 4.2 months obtained in our study in patients with pNET is comparable with the PFS duration of 4.5 and 5.5 months in the placebo arms of the randomized sunitinib (Raymond et al. 2011) and everolimus trials (Yao et al. 2011) respectively. The PFS duration of 10.5 months obtained in the carcinoid cohort of our study is comparable to that of 11.2 months in the placebo arm of the randomized study of everolimus in patients with advanced carcinoid (Pavel et al. 2011). The median PFS was longer in patients receiving octreotide LAR (14.4 months) than in patients who did not receive octreotide (4.1 months). While a synergistic effect between ganitumab and SSAs is possible, these differences in PFS may also have been due to patient selection or to a cytostatic effect of octreotide alone.

Our negative results are consistent with the lack of clinical activity associated with another IGF pathway inhibitor in NET (Reidy-Lagunes et al. 2012) as well as recent results with ganitumab in pancreatic adenocarcinoma, in which a randomized trial of gemcitabine with our without ganitumab was stopped early due to lack of efficacy (www.amgen.com/media/media_pr_detail.jsp?releaseID=1723925). Given the apparent pivotal role played by IGF signaling in preclinical studies of NET and other cancers, it is in many respects surprising that treatment with ganitumab and other IGF pathway inhibitors has not been associated with more antitumor activity. It is possible that IGF1R blockade alone is not sufficient to block IGF signaling. Resistance to IGF1R blockade may be mediated by multiple mechanisms, including upregulation of alternate tyrosine kinase receptors such as the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) or Her2 (Haluska et al. 2008), overexpression of additional IGF pathway components, including IGF2 and INSR (Garofalo et al. 2011), or receptor-independent downstream activation of the PI3K/AKT pathway as well as alternate signal transduction pathways. Additional preclinical work will be necessary to elucidate specific patterns of resistance in NETs and to suggest combination therapies that are likely to enhance tumoral sensitivity to IGFR1 inhibition. For example, if resistance is mediated by downstream upregulation of the PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway, then studies of combination treatment with an mTOR inhibitor may be warranted.

In conclusion, our study failed to demonstrate significant antitumor activity associated with ganitumab monotherapy in NET. Given strong preclinical evidence implicating the IGF pathway in NET pathogenesis, further studies assessing the role of the IGF pathway in NET, together with investigation of resistance mechanisms to single-agent IGF1R blockade in this setting, are warranted.

Acknowledgments

Funding

This work was supported with funding from Amgen, Inc.

Footnotes

Declaration of interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest that could be perceived as prejudicing the impartiality of the research reported.

References

- Beltran PJ, Mitchell P, Chung YA, Cajulis E, Lu J, Belmontes B, Ho J, Tsai MM, Zhu M, Vonderfecht S, et al. AMG 479, a fully human anti-insulin-like growth factor receptor type I monoclonal antibody, inhibits the growth and survival of pancreatic carcinoma cells. Molecular Cancer Therapeutics. 2009;8:1095–1105. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-08-1171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garofalo C, Manara MC, Nicoletti G, Marino MT, Lollini PL, Astolfi A, Pandini G, López-Guerrero JA, Schaefer KL, Belfiore A, et al. Efficacy of and resistance to anti-IGF-1R therapies in Ewing’s sarcoma is dependent on insulin receptor signaling. Oncogene. 2011;30:2730–2740. doi: 10.1038/onc.2010.640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haluska P, Carboni JM, TenEyck C, Attar RM, Hou X, Yu C, Sagar M, Wong TW, Gottardis MM, Erlichman C. HER receptor signaling confers resistance to the insulin-like growth factor-I receptor inhibitor, BMS-536924. Molecular Cancer Therapeutics. 2008;7:2589–2598. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-08-0493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hopfner M, Baradari V, Huether A, Schofl C, Scherubl H. The insulin-like growth factor receptor 1 is a promising target for novel treatment approaches in neuroendocrine gastrointestinal tumours. Endocrine-Related Cancer. 2006;13:135–149. doi: 10.1677/erc.1.01090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiao Y, Shi C, Edil BH, de Wilde RF, Klimstra DS, Maitra A, Schulick RD, Tang LH, Wolfgang CL, Choti MA, et al. DAXX/ATRX, MEN1, and mTOR pathway genes are frequently altered in pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors. Science. 2011;331:1199–1203. doi: 10.1126/science.1200609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kindler HL, Richards DA, Garbo LE, Stephenson JJ, Jr, Rocha-Lima CM, Safran H, Chan D, Kocs DM, Galimi F, McGreivy J, et al. A randomized, placebo-controlled phase 2 study of ganitumab (AMG 479) or conatumumab (AMG 655) in combination with gemcitabine in patients with metastatic pancreatic cancer. Annals of Oncology. 2012;23:2834–2842. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mds142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klimstra DS, Modlin IR, Coppola D, Lloyd RV, Suster S. The pathologic classification of neuroendocrine tumors: a review of nomenclature, grading, and staging systems. Pancreas. 2010;39:707–712. doi: 10.1097/MPA.0b013e3181ec124e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kouvaraki MA, Ajani JA, Hoff P, Wolff R, Evans DB, Lozano R, Yao JC. Fluorouracil, doxorubicin, and streptozocin in the treatment of patients with locally advanced and metastatic pancreatic endocrine carcinomas. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2004;22:4762–4771. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.04.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kulke MH, Stuart K, Enzinger PC, Clark JW, Muzikansky A, Vincitore M, Michelini A, Fuchs CS. Phase II study of temozolomide and thalidomide in patients with metastatic neuroendocrine tumors. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2006;24:401–406. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.03.6046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kulke MH, Lenz HJ, Meropol NJ, Posey J, Ryan DP, Picus J, Bergsland E, Stuart K, Tye L, Huang X, et al. Activity of sunitinib in patients with advanced neuroendocrine tumors. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2008;26:3403–3410. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.15.9020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kulke MH, Siu LL, Tepper JE, Fisher G, Jaffe D, Haller DG, Ellis LM, Benedetti JK, Bergsland EK, Hobday TJ, et al. Future directions in the treatment of neuroendocrine tumors: consensus report of the National Cancer Institute Neuroendocrine Tumor clinical trials planning meeting. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2011;29:934–943. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.33.2056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kulke MH, Benson AB, III, Bergsland E, Berlin JD, Blaszkowsky LS, Choti MA, Clark OH, Doherty GM, Eason J, Emerson L, et al. Neuroendocrine tumors. Journal of the National Comprehensive Cancer Network. 2012;10:724–764. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2012.0075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kvols LK, Moertel CG, O’Connell MJ, Schutt AJ, Rubin J, Hahn RG. Treatment of the malignant carcinoid syndrome. Evaluation of a long-acting somatostatin analogue. New England Journal of Medicine. 1986;315:663–666. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198609113151102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moertel CG, Lefkopoulo M, Lipsitz S, Hahn RG, Klaassen D. Streptozocin–doxorubicin, streptozocin–fluorouracil or chlorozotocin in the treatment of advanced islet-cell carcinoma. New England Journal of Medicine. 1992;326:519–523. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199202203260804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pavel ME, Hainsworth JD, Baudin E, Peeters M, Hörsch D, Winkler RE, Klimovsky J, Lebwohl D, Jehl V, Wolin EM, et al. Everolimus plus octreotide long-acting repeatable for the treatment of advanced neuroendocrine tumours associated with carcinoid syndrome (RADIANT-2): a randomised, placebo-controlled, phase 3 study. Lancet. 2011;378:2005–2012. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61742-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raymond E, Dahan L, Raoul JL, Bang YJ, Borbath I, Lombard-Bohas C, Valle J, Metrakos P, Smith D, Vinik A, et al. Sunitinib malate for the treatment of pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors. New England Journal of Medicine. 2011;364:501–513. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1003825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reidy-Lagunes DL, Vakiani E, Segal MF, Hollywood EM, Tang LH, Solit DB, Pietanza MC, Capanu M, Saltz LB. A phase 2 study of the insulin-like growth factor-1 receptor inhibitor MK-0646 in patients with metastatic, well-differentiated neuroendocrine tumors. Cancer. 2012;118:4795–4800. doi: 10.1002/cncr.27459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rinke A, Muller HH, Schade-Brittinger C, Klose KJ, Barth P, Wied M, Mayer C, Aminossadati B, Pape UF, Bläker M, et al. Placebo-controlled, double-blind, prospective, randomized study on the effect of octreotide LAR in the control of tumor growth in patients with metastatic neuroendocrine midgut tumors: a report from the PROMID Study Group. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2009;27:4656–4663. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.22.8510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strosberg JR, Fine RL, Choi J, Nasir A, Coppola D, Chen DT, Helm J, Kvols L. First-line chemotherapy with capecitabine and temozolomide in patients with metastatic pancreatic endocrine carcinomas. Cancer. 2011;117:268–275. doi: 10.1002/cncr.25425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tolcher AW, Sarantopoulos J, Patnaik A, Papadopoulos K, Lin CC, Rodon J, Murphy B, Roth B, McCaffery I, Gorski KS, et al. Phase I, pharmacokinetic, and pharmacodynamic study of AMG 479, a fully human monoclonal antibody to insulin-like growth factor receptor 1. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2009;27:5800–5807. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.23.6745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- von Wichert G, Jehle PM, Hoeflich A, Koschnick S, Dralle H, Wolf E, Wiedenmann B, Boehm BO, Adler G, Seufferlein T. Insulin-like growth factor-I is an autocrine regulator of chromogranin A secretion and growth in human neuroendocrine tumor cells. Cancer Research. 2000;60:4573–4581. doi: 10.1016/S0016-5085(00)84296-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wulbrand U, Remmert G, Zofel P, Wied M, Arnold R, Fehmann HC. mRNA expression patterns of insulin-like growth factor system components in human neuroendocrine tumours. European Journal of Clinical Investigation. 2000;30:729–739. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2362.2000.00700.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yao JC, Phan A, Hoff PM, Chen HX, Charnsangavej C, Yeung SC, Hess K, Ng C, Abbruzzese JL, Ajani JA. Targeting vascular endothelial growth factor in advanced carcinoid tumor: a random assignment phase II study of depot octreotide with bevacizumab and pegylated interferon α-2b. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2008;26:1316–1323. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.13.6374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yao JC, Lombard-Bohas C, Baudin E, Kvols LK, Rougier P, Ruszniewski P, Hoosen S, St Peter J, Haas T, Lebwohl D, et al. Daily oral everolimus activity in patients with metastatic pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors after failure of cytotoxic chemotherapy: a phase II trial. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2010;28:69–76. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.24.2669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yao JC, Shah MH, Ito T, Bohas CL, Wolin EM, Van Cutsem E, Hobday TJ, Okusaka T, Capdevila J, de Vries EG, et al. Everolimus for advanced pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors. New England Journal of Medicine. 2011;364:514–523. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1009290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]