Abstract

Heparan sulfate (HS) and chondroitin sulfate (CS) glycosaminoglycans (GAG) are proteoglycan-associated polysaccharides with essential functions in animals. They have been studied extensively by genetic manipulation of biosynthetic enzymes, but chemical tools for probing GAG function are limited. HS and CS possess a conserved xylose residue that links the polysaccharide chain to a protein backbone. Here we report that, in zebrafish embryos, the peptide-proximal xylose residue can be metabolically replaced with a chain-terminating 4-azido-4-deoxyxylose (4-XylAz) residue by administration of UDP-4-azido-4-deoxyxylose (UDP-4-XylAz). UDP-4-XylAz disrupted both HS and CS biosynthesis and caused developmental abnormalities reminiscent of GAG biosynthesis and laminin mutants. The azide substituent of protein-bound 4-XylAz allowed for rapid visualization of the organismal sites of chain termination in vivo through bioorthogonal reaction with fluorescent cyclooctyne probes. UDP-4-XylAz therefore complements genetic tools for studies of GAG function in zebrafish embryogenesis.

Keywords: click chemistry, glycosaminoglycan biosynthesis, glycosylation, inhibitor, zebrafish

Glycosaminoglycans (GAGs), linear polysaccharides composed of repeating disaccharides, are important components of animal cell surfaces and the extracellular matrix. The most widely studied GAGs are heparan sulfate (HS) and chondroitin sulfate (CS), which have distinct disaccharide repeats but share a common core tetrasaccharide that links them to an underlying protein scaffold (Figure 1A). Variable sulfation along a GAG chain can generate an enormous array of structures, allowing them to interact with diverse biomolecules. For example, GAG binding to signaling molecules, including members of the Hedgehog, TGFβ and FGF families, and to extracellular matrix molecules and basement membrane components such as laminin, is essential for proper animal development.[1,2] Accordingly, mutations in the GAG biosynthetic machinery can lead to dramatic phenotypes.[3] For example, mice lacking Ext1 or Ext2, the enzymes responsible for polymerizing HS, die in early development from defective gastrulation.[4–6] GAG biosynthesis mutations in zebrafish embryos have been shown to cause craniofacial developmental defects.[7]

Figure 1.

Xylose initiates diverse glycosaminoglycan structures and can therefore be targeted for metabolic replacement with a visualizable chain-truncating analog. A) Heparan sulfate and chondroitin sulfate structures. R1 = H or SO3—; R2 = Ac or SO3—. GlcA, glucuronic acid; IdoA, iduronic acid; GlcNAc, N-acetylglucosamine; GalNAc, N-acetylgalactosamine; Gal, Galactose; Xyl, Xylose; astrisk, position at which epimerization can occur. B) With an azide in place of the hydroxyl group that is elaborated during GAG enogation, 4-XylAz both inhibits GAG biosynthesis and enables visualization using a cyclooctyne probe conjugated to a fluorophore. Green star, fluorophore.

Studies of GAG biology typically involve genetic manipulation of biosynthetic enzymes (e.g., via gene disruption, antisense knockdown or RNAi) followed by phenotypic analysis. However, the enzymes may have functions beyond their roles in catalysis. For example, several proteins involved in HS biosynthesis are known to exist in multi-enzyme complexes in the Golgi compartment.[8–10] As a consequence, diminished expression of one enzyme can indirectly affect the activity, stability and subcellular localization of others.[8–10] In other areas of biology, such complexities have motivated the development of complementary chemical tools that target proteins of interest in a fundamentally different manner.[11]

Chemical tools for modulating the biosynthesis of GAGs in cells and organisms are presently quite limited. The majority of work has focused on aryl xylosides as “primers” of GAG biosynthesis.[12,13] As the first sugar of the conserved core tetrasaccharide (Figure 1A), xylose is attached through a β-linkage to serine residues by the action of one or more protein xylosyltransferases (XylTs).[14] The xylose residue is then elaborated with three more conserved residues before commitment to a specific GAG chain. β-Xylosides with hydrophobic aglycones can mimic xylosylated proteins and compete for the elaborating enzymes. These compounds do not technically inhibit GAG biosynthesis; rather, they provide an alternative substrate for GAG elaboration and lead to the production of proteoglycans without GAGs. Further, the GAG-modified β-xylosides are secreted into the extracellular environment where they can acquire new activities, confounding interpretation of the observed biological effects.[15] Recently, this approach was modified to generate true inhibitors of GAG biosynthesis by replacing the C-4 hydroxyl group of β-xylosides, the position from which the GAG chain is polymerized, with a fluorine atom.[16,17] These fluorinated xylose analogs effectively inhibit GAG biosynthesis in cultured cells.

Chain-terminating metabolic inhibitors comprise a second though less well-developed class of GAG biosynthesis disruptors.[18–21] These compounds are simple deoxy or fluorinated sugars that lack the key hydroxyl group needed for polysaccharide elongation. Their metabolic conversion to nucleotide-sugar glycosyl donors and subsequent enzymatic incorporation into growing GAG chains leads to truncation and, therefore, incomplete GAG biosynthesis. A complication inherent to this approach is that most GAG monosaccharide constituents are widely distributed among other glycan types. The corresponding deoxy and fluoro analogs therefore perturb numerous glycan structures in addition to GAGs.[19,22] The exception is xylose, which is almost exclusively found in GAGs.[23,24] But chain-terminating xylose-based GAG inhibitors have not been explored, perhaps due to the absence of a salvage pathway that would convert simple xylose analogs to the UDP-activated form used by protein xylosyltransferases.[25] This problem would be obviated by the direct use of UDP-xylose analogs as chain-terminating metabolic inhibitors, but the anionic nature of nucleotide sugars renders them cell membrane impermeant.

While nucleotide sugars cannot be effectively administered to cultured cells, the situation is quite different for zebrafish embryos. Our lab as well as Wu and coworkers have recently shown that nucleotide sugars can be delivered to all the cells of a zebrafish embryo by microinjection into the yolk sack at the 1–4 cell stage.[26–28] This observation suggested a route to inhibiting GAG biosynthesis with UDP-xylose analogs. In addition to providing a convenient route for delivery of nucleotide sugars, zebrafish have become a powerful, well-established animal model for vertebrate development, a biological setting in which GAGs are known to have numerous functions.[3]

Here we report that UDP-4-azido-4-deoxyxylose (UDP-4-XylAz) acts as chain-terminating metabolic inhibitor of GAG biosynthesis in developing zebrafish. After injection into zebrafish embryos, the compound is recognized as a substrate by one or more protein XylTs, resulting in the addition of 4-XylAz to sites where GAGs would normally be elaborated. Replacement of the C-4 hydroxyl group with an azide both inhibits GAG elaboration and enables visualization of sites within the embryo where inhibition has occurred via reaction with cyclooctyne-functionalized imaging probes (Figure 1B).[26,27,29] This dual-function inhibitor adds to the much-needed chemical toolkit for studying GAGs in vivo.

At the outset of this work we prepared the panel of azido UDP-xylose analogs shown in Figure 2, wherein each hydroxyl group of xylose was individually replaced with an azide group. To prepare UDP-4-XylAz, we began by selectively benzoylating the 1-, 2- and 3-hydroxyl groups of L-arabinose, the C-4 epimer of xylose, using a known procedure.[30] The free hydroxyl group of 1,2,3-tri-O-benzoyl-L-arabinose (4) was then converted to an azide, giving 5 as shown in Scheme 1. The benzoyl groups were exchanged with acetyl groups to facilitate production of the desired α anomer during phosphorylation of the C-1 hydroxyl group in a later step. Selective deprotection of the anomeric position with hydrazine acetate produced 6, which was reacted with diallyl-N,N-diisopropylphosphoramidite to give the globally protected xylose-1-phosphate analog 7.[31] After deprotection of the phosphate group and immediate reaction with UMP-N-methylimidazolide, UDP-4-XylAz was obtained.[31] Similar syntheses for UDP-2-XylAz (2) and UDP-3-XylAz (3) are detailed in the Supporting Information (Schemes S1 and S2).

Figure 2.

UDP-XylAz analogs. UDP-4-XylAz (1), UDP-2-XylAz (2), and UDP-3-XylAz (3).

Scheme 1.

UDP-4-XylAz synthesis. Reagents/Conditions: (a) i. Tf2O, pyridine, DCM, −20 °C; ii. LiN3, DMF, rt, 85% (2 steps); (b) i. NaOMe, MeOH, rt; ii. Ac2O, pyridine, 0°C to rt, 80% (2 steps); (c) hydrazine acetate, DMF, rt, 54%; (d) i. diallyl N,N-diisopropylphosphoramidite, 1H-tetrazole, DCM, rt; ii. mCPBA, DCM, −40 °C, 31% (2 steps); (e) i. Pd(PPh3)4, sodium p-toluenesulfinate, THF, MeOH, rt; ii. UMP-N-methylimidazolide, MeCN, 0 °C; iii. NEt3, MeOH, water, rt, 22% (3 steps).

Each azido UDP-xylose derivative, 1–3, was tested for its ability to deliver azidoxylose into zebrafish proteoglycans. In these experiments, 50–100 pmol of 1, 2 or 3 was injected into zebrafish embryos at the 1–4 cell stage. After developing to 24 hours post fertilization (hpf), embryos were incubated with difluorocyclooctyne-AlexaFluor 488 (DIFO-488, 200 μM), mounted in agarose, and imaged by confocal microscopy.[26,27,29,32] While no labeling was detectable for embryos injected with 2 or 3 (Figure S3), azide-dependent labeling was observed for embryos injected with UDP-4-XylAz (1) (Figure 3). Flow cytometry, which provides more sensitive detection than fluorescence microscopy, confirmed that azide-dependent labeling was only observed after treatment with 1 (Figure S4).

Figure 3.

UDP-4-XylAz enables in vivo imaging of the site of inhibition in zebrafish embryos. Scale bars: 10x, 200 μm; 20x, 50 μm.

To establish that UDP-4-XylAz delivers 4-XylAz to sites of GAG glycosylation, we performed biochemical assays with human xylosyltransferases 1 and 2 (XylT1 and 2), which are known to initiate GAG glycosylation.[33] An acceptor peptide was incubated with UDP-4-XylAz and either XylT1 or XylT2 and the glycopeptide product was analyzed by mass spectrometry (Figure S5). While XylT1 transferred 4-XylAz to the acceptor peptide, XylT2 was inactive on the substrate. As human XylT1 is highly homologous to its zebrafish counterpart, sharing 75% identity, this result supports the claim that XylT1 is able to transfer UDP-4-XylAz onto proteoglycans in zebrafish.

Having confirmed that XylT1 can transfer UDP-4-XylAz to an acceptor peptide in vitro, we disrupted translation of XylT1 in zebrafish using a splice-blocking morpholino oligonucleotide (MO) and analyzed the effect on 4-XylAz labeling.[33] We used a previously-reported XylT1 MO and verified its effect on the XylT1 transcript by RT-PCR (Figures S6 and S7).[33] Then, embryos were injected with 50 pmol of UDP-4-XylAz alone or 50 pmol of UDP-4-XylAz and 6 ng of XylT1 MO, and were allowed to develop to 24 hpf. Enveloping layer cells were labeled with NHS-647 and the embryos were dissociated into single cells, incubated with DIFO-biotin followed by avidin-AlexaFluor-488, and analyzed by flow cytometry. Knockdown of XylT1 activity by MO treatment reduced UDP-4-XylAz-dependent fluorescence labeling by 30% (Figure S8). This partial decrease in labeling was expected because embryos have maternally provided XylT activity that cannot be affected by the XylT1 MO.[33]

We next sought to ensure that the decrease in labeling upon treatment with the MO was not due to a non-specific, global perturbation of glycan biosynthesis. Fucose is a monosaccharide not found in zebrafish GAGs; its incorporation into cell-surface glycans should therefore be unaffected by the XylT1 MO. To determine the effects of the XylT1 MO on cell-surface fucosylation, a proxy for non-GAG glycosylation, we dissociated MO-treated embryos into single cells, incubated them with a biotinylated Aleuria aurantia lectin that recognizes fucose, incubated with avidin-AlexaFluor-488, and measured for fluorescence by flow cytometry (Figure S9).[27] Comparison of embryos injected with the XylT1 MO and untreated embryos confirmed that the MO had no effect on fucosylation, and, by inference, global glycosylation.

After confirming that replacement of the C-4 hydroxyl group of xylose with an azide prevents elaboration by β4-galatosyltransferase (β4GalT7)[34] in vitro (Figure S10), we investigated the effects of UDP-4-XylAz treatment on the total amount of HS and CS per embryo, which we quantified using a previously described method.[7] GAGs were isolated from UDP-4-XylAz-treated or untreated embryos, enzymatically degraded into disaccharides, and analyzed by reverse phase ion pairing HPLC. Treatment with UDP-4-XylAz caused a reduction in HS and CS levels by 47% and 77%, respectively (Figure 4, A and B). The unequal effect of the inhibitor on HS and CS levels is consistent with observations in zebrafish mutants with genetic knockdowns of the GAG biosynthesis enzymes responsible for constructing the core tetrasaccharide.[7] We further analyzed the extent of sulfation of HS and CS in the presence and absence of the metabolic inhibitor. In line with the reduction in GAG levels, HS and CS sulfation were decreased by 53% and 83%, respectively. In parallel, we analyzed the disaccharide compositions of HS and CS in the presence and absence of UDP-4-XylAz. In agreement with its effects on total sulfation, the inhibitor did not appreciably alter the HS or CS disaccharide composition (Figure 4, E and F).

Figure 4.

Effect of UDP-4-XylAz on HS expression (A), CS expression (B), HS total sulfation (C), CS total sulfation (D), HS disaccharide composition (E), and CS disaccharide composition (F). Grey bars, untreated; black bars, UDP-4-XylAz. Error bars denote the standard deviation from three replicate experiments. * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001.

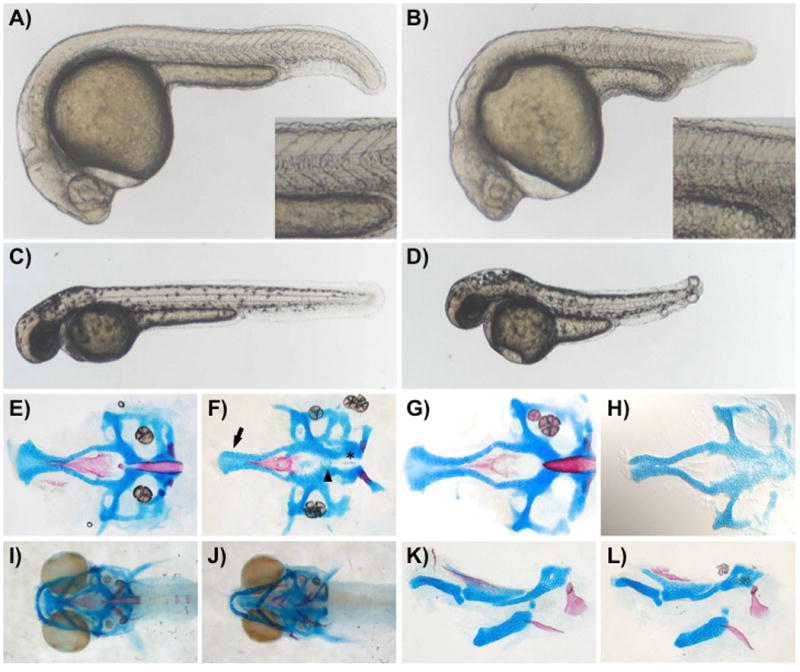

Finally, we examined the morphological effects of GAG disruption by UDP-4-XylAz injection. Zebrafish embryos treated with the metabolic inhibitor displayed an observable phenotype that is subtle at early stages (18 hpf, data not shown) and becomes more prominent as the embryo develops (Figure 5). UDP-4-XylAz-treated fish had a shortened axis, disorganized brain, small eyes, notochord defects, and abnormally shaped myotomes by 24 hpf, as well as prominent tail blistering by 48 hpf (Figure 5, A-D). These phenotypes are reminiscent of those observed for zebrafish with GAG or proteoglycan defects induced by genetic methods,[7,35] and of zebrafish laminin (lam) mutants, particularly lama1/bashful, lamb1a/grumpy, and lamc1/sleepy (sly).[36–39] By 6 dpf, craniofacial abnormalities were apparent in live UDP-4-XylAz-treated fish. At this stage, the craniofacial skeleton is comprised of a simple pattern of cartilage and bone elements; thus, we utilized stains for cartilage and bone (alcian and alizarin, respectfully) to better understand the impact of UDP-4-XylAz on these structures. In inhibitor-treated embryos, alcian staining of cartilaginous elements revealed defects in the neurocranium, including a narrow ethmoid plate and less cohesive midline cartilage cells, while alizarin staining of developing bone tissues revealed a lack of notochord differentiation (Figure 5, E and F). A similar ethmoid plate phenotype is observed in embryos with deficiencies in Hedgehog signaling, defects in cytokine signaling, or excess retinoic acid signaling,[40–42] yet the alcian stains are most strikingly similar to those of lamb1ab1166 mutants (Figure 5, compare E and F with G and H), especially in light of other phenotypic similarities between inhibitor-treated and laminin mutant embryos. Another craniofacial element defect in UDP-4-XylAz-injected embryos includes a narrowing of the lower jaw elements (Figure 5, I and J); otherwise visceral skeletal elements, including the pharyngeal arches (not shown) are largely normal (Figure 5, K and L). During early development, Laminin and proteoglycan interactions are critical for basement membrane integrity and interactions with growth factors; the phenotypic similarities of UDP-4-XylAz-injected and lamb1ab1166 mutant embryos suggest that the inhibitor may interfere with these interactions.43

Figure 5.

UDP-4-XylAz injection causes embryological defects. Compared to 24 hpf controls (A), injected embryos (B) have a shortened axis, disorganized brain with enlarged hindbrain ventricle, small eyes, and abnormally shaped myotomes (see inset). By 48 hpf, notochord defects and tail blistering are prominent in treated versus control embryos (C and D). At 6 dpf, treated embryos have neurocranium defects, including a narrow ethmoid plate (arrow) and less cohesive midline cartilagenous cells (arrowhead), and the absence of a differentiated notochord (asterisk) (E and F), phenotypes strikingly similar to that of lamininb1ab1166 mutant embryos (G and H). Another craniofacial defect in treated embryos is the narrowing of the lower jaw (I and J); visceral skeletal elements (K and L), including the pharyngeal arches (not shown) are largely normal. Alcian-stained cartilage elements are blue; Alizarin-stained bone elements are red. Although the alizarin staining in the lamb1ab1166 mutant panel had faded significantly prior to imaging, additional preparations confirm the notochord defect described for laminin mutants.37

In conclusion, UDP-4-XylAz is an effective chain-terminating metabolic inhibitor of GAG biosynthesis in zebrafish. The compound has a unique attribute in that its organismal sites of inhibition can be visualized in vivo through bioorthogonal reaction with fluorescent cyclooctynes. Comparison of GAGs from UDP-4-XylAz and untreated embryos revealed differences in GAG abundance that likely cause the specific embryological defects observed. This metabolic inhibitor should aid in elucidating novel roles of GAG chains during vertebrate development.

Experimental Section

General procedure for visualizing GAG inhibition in vivo: At the 1-4 cell stage, zebrafish embryos were injected with 50 pmol of UDP-4-XylAz. After developing to 24 hpf, zebrafish were incubated in a 200 μM solution of DIFO-488 for 1 h at 28.5 °C, washed, and imaged by confocal microscopy.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

We thank J. Jewett, E. Sletten, B. Belardi, J. Hudak, T. Gallagher, S. Laughlin, B. Swarts, for helpful discussions and for critical reading of the manuscript. This work was supported by a grant to C.R.B. from the NIH (GM58867) and a grant to S.L.A. from the NIH (GM61952). The lamb1ab1166 allele was isolated in a screen supported by NIH grant HD22486 (to Charles B. Kimmel).

Supporting information for this article is available on the WWW under http://www.angewandte.org

Contributor Information

Brendan J. Beahm, Department of Chemistry and Molecular and Cell Biology, Howard Hughes Medical Institute, University of California, Berkeley, CA 94720 (USA)

Karen W. Dehnert, Department of Chemistry and Molecular and Cell Biology, Howard Hughes Medical Institute, University of California, Berkeley, CA 94720 (USA)

Nicolas L. Derr, Departments of Molecular Genetics and Molecular and Cellular Biochemistry; Center for RNA Biology, Ohio State University, Columbus, OH 43210 (USA)

Joachim Kuhn, Institut für Laboratoriums- und Transfusionmedizin, Herz- und Diabeteszentrum Nordrhein-Westfalen Georgstraße 11, 32545 Bad Oeynhausen (Germany).

Johann K. Eberhart, Department of Molecular Biosciences, University of Texas, Austin, TX 78713 (USA)

Dorothe Spillmann, Department of Medical Biochemistry and Microbiology, The Biomedical Center, Uppsala University, Husargatan 3, PO Box 582, SE-751 23, Uppsala, Sweden.

Sharon L. Amacher, Departments of Molecular Genetics and Molecular and Cellular Biochemistry; Center for RNA Biology, Ohio State University, Columbus, OH 43210 (USA)

Carolyn R. Bertozzi, Email: crb@berkeley.edu, Department of Chemistry and Molecular and Cell Biology, Howard Hughes Medical Institute, University of California, Berkeley, CA 94720 (USA).

References

- 1.Nybakken K, Perrimon N. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2002;1573:280–291. doi: 10.1016/s0304-4165(02)00395-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hohenester E, Yurchenco PD. Cell Adhes Migr. 2013;7:56–63. doi: 10.4161/cam.21831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bülow HE, Hobert O. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2006;22:375–407. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.22.010605.093433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lin X, Wei G, Shi Z, Dryer L, Esko JD, Wells DE, Matzuk MM. Dev Biol. 2000;224:299–311. doi: 10.1006/dbio.2000.9798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mitchell KJ, et al. Nat Genet. 2001;28:241–249. doi: 10.1038/90074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Stickens D, Zak BM, Rougier N, Esko JD, Werb Z. Dev Camb Engl. 2005;132:5055–5068. doi: 10.1242/dev.02088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Holmborn K, et al. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:33905–33916. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.401646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McCormick C, Duncan G, Goutsos KT, Tufaro F. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2000;97:668–673. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.2.668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Senay C, Lind T, Muguruma K, Tone Y, Kitagawa H, Sugahara K, Lidholt K, Lindahl U, Kusche-Gullberg M. EMBO Rep. 2000;1:282–286. doi: 10.1093/embo-reports/kvd045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pinhal MA, Smith B, Olson S, Aikawa J, Kimata K, Esko JD. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:12984–12989. doi: 10.1073/pnas.241175798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dar AC, Shokat KM. Annu Rev Biochem. 2011;80:769–795. doi: 10.1146/annurev-biochem-090308-173656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Okayama M, Kimata K, Suzuki S. J Biochem (Tokyo) 1973;74:1069–1073. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schwartz NB, Galligani L, Ho PL, Dorfman A. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1974;71:4047–4051. doi: 10.1073/pnas.71.10.4047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wilson IBH. Cell Mol Life Sci CMLS. 2004;61:794–809. doi: 10.1007/s00018-003-3278-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Margolis RK, Goossen B, Tekotte H, Hilgenberg L, Margolis RU. J Cell Sci. 1991;99(Pt 2):237–246. doi: 10.1242/jcs.99.2.237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Garud DR, Tran VM, Victor XV, Koketsu M, Kuberan B. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:28881–28887. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M805939200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tsuzuki Y, Nguyen TKN, Garud DR, Kuberan B, Koketsu M. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2010;20:7269–7273. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2010.10.085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Thomas SS, Plenkiewicz J, Ison ER, Bols M, Zou W, Szarek WA, Kisilevsky R. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1995;1272:37–48. doi: 10.1016/0925-4439(95)00065-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hull RL, Zraika S, Udayasankar J, Kisilevsky R, Szarek WA, Wight TN, Kahn SE. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2007;293:C1586–1593. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00208.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nigro J, Wang A, Mukhopadhyay D, Lauer M, Midura RJ, Sackstein R, Hascall VC. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:16832–16839. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.002956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Van Wijk XM, et al. ACS Chem Biol. 2013;8:2331–2338. doi: 10.1021/cb4004332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dimitroff CJ, Bernacki RJ, Sackstein R. Blood. 2003;101:602–610. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-06-1736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nishimura H, Kawabata S, Kisiel W, Hase S, Ikenaka T, Takao T, Shimonishi Y, Iwanaga S. J Biol Chem. 1989;264:20320–20325. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Inamori Ki, Yoshida-Moriguchi T, Hara Y, Anderson ME, Yu L, Campbell KP. Science. 2012;335:93–96. doi: 10.1126/science.1214115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bakker H, et al. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:2576–2583. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M804394200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Baskin JM, Dehnert KW, Laughlin ST, Amacher SL, Bertozzi CR. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:10360–10365. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0912081107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dehnert KW, Beahm BJ, Huynh TT, Baskin JM, Laughlin ST, Wang W, Wu P, Amacher SL, Bertozzi CR. ACS Chem Biol. 2011;6:547–552. doi: 10.1021/cb100284d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Soriano del Amo D, Wang W, Jiang H, Besanceney C, Yan AC, Levy M, Liu Y, Marlow FL, Wu P. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132:16893–16899. doi: 10.1021/ja106553e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Laughlin ST, Baskin JM, Amacher SL, Bertozzi CR. Science. 2008;320:664–667. doi: 10.1126/science.1155106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Batey JF, Bullock C, O'Brien E, Williams JM. Carbohydr Res. 1975;43:43–50. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hang HC, Yu C, Pratt MR, Bertozzi CR. J Am Chem Soc. 2004;126:6–7. doi: 10.1021/ja037692m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Baskin JM, Prescher JA, Laughlin ST, Agard NJ, Chang PV, Miller IA, Lo A, Codelli JA, Bertozzi CR. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:16793–16797. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0707090104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mueller M. Ph D thesis. The University of Chicago; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nakamura Y, Haines N, Chen J, Okajima T, Furukawa K, Urano T, Stanley P, Irvine KD, Furukawa K. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:46280–46288. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M203873200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Topczewski J, Sepich DS, Myers DC, Walker C, Amores A, Lele Z, Hammerschmidt M, Postlethwait J, Solnica-Krezel L. Dev Cell. 2001;1:251–264. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(01)00005-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Schier AF, et al. Development. 1996;123:165–178. doi: 10.1242/dev.123.1.165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Parsons MJ, Pollard SM, Saúde L, Feldman B, Coutinho P, Hirst EMA, Stemple DL. Development. 2002;129:3137–3146. doi: 10.1242/dev.129.13.3137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Paulus JD, Halloran MC. Dev Dyn. 2006;235:213–224. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.20604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Dolez M, Nicolas JF, Hirsinger E. Development. 2011;138:97–106. doi: 10.1242/dev.053975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wada N, Javidan Y, Nelson S, Carney TJ, Kelsh RN, Schilling TF. Dev Camb Engl. 2005;132:3977–3988. doi: 10.1242/dev.01943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Laue K, Jänicke M, Plaster N, Sonntag C, Hammerschmidt M. Dev Camb Engl. 2008;135:3775–3787. doi: 10.1242/dev.021238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Olesnicky Killian EC, Birkholz DA, Artinger KB. Dev Biol. 2009;333:161–172. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2009.06.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Davis GE, Klier FG, Engvall E, Cornbrooks C, Varon S, Manthorpe M. Neurochem Res. 1987;12:909–921. doi: 10.1007/BF00966313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.