Abstract

The development of targeted therapies has revolutionized the treatment of cancer patients. The identification of ‘druggable’ oncogenic kinases and the creation of small molecule inhibitors designed to specifically target these mutant kinases has become an important therapeutic paradigm across several different malignancies. Often these inhibitors induce dramatic clinical responses in molecularly defined cohorts. However, resistance to such targeted therapies is an inevitable consequence of this therapeutic approach. Resistance can be either primary (de novo) or acquired. Mechanisms leading to primary resistance may be categorized as tumor intrinsic factors or as patient/drug specific factors. Acquired resistance may be mediated by target gene modification, activation of ‘bypass tracks’ which serve as compensatory signaling loops, or histological transformation. This brief review is a snapshot of the complex problem of therapeutic resistance, with a focus on resistance to kinase inhibitors in EGFR mutant and ALK rearranged non-small cell lung cancer, BRAF mutant melanoma, and BCR-ABL positive chronic myeloid leukemia. We will describe specific mechanisms of primary and acquired resistance and then review emerging strategies to delay or overcome drug resistance.

Background

Targeted cancer therapies are drugs designed to interfere with specific mutant signaling proteins. In the setting of “oncogene addiction”, certain tumors become dependent on a single oncogenic pathway to promote tumor growth and survival. This ‘addiction’ can serve as an ‘Achilles heel’ to target cancers with increased precision. Beginning with the marked success of the tyrosine kinase inhibitor (TKI) imatinib in BCR-ABL-positive chronic myeloid leukemia (CML), the therapeutic targeting of oncogenes has emerged as a preeminent treatment paradigm for multiple other oncogene-driven malignancies. In addition to CML, this approach has been successful in EGFR mutant non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), ALK- and ROS1- rearranged NSCLC, BRAF mutant melanoma, KIT mutant melanoma and gastrointestinal stromal tumor (GIST), and HER2 amplified breast cancer (1-7). In each case, the identification of the ‘driver’ mutation or rearrangement within the tumor and the administration of genotype-directed anti-tumor therapy have resulted in improved clinical response rates within the specific molecularly-defined cohort.

Unfortunately, despite these promising results, a common theme amongst patients with oncogene-driven cancers treated with small molecule inhibitors is drug resistance. The development of drug resistance remains a major limitation and threat to the successful management of advanced cancer. In this review, we will formally define therapeutic resistance, review mechanisms of resistance to kinase inhibitors, and provide examples of therapeutic strategies to attempt to delay or overcome resistance. Given the complexity of the topic, this review will focus on selected tumor types, namely NSCLC, melanoma, and CML. However, many of the concepts discussed are broadly applicable amongst several tumor types and can serve as paradigms for understanding resistance in other malignancies.

Definition of Therapeutic Resistance

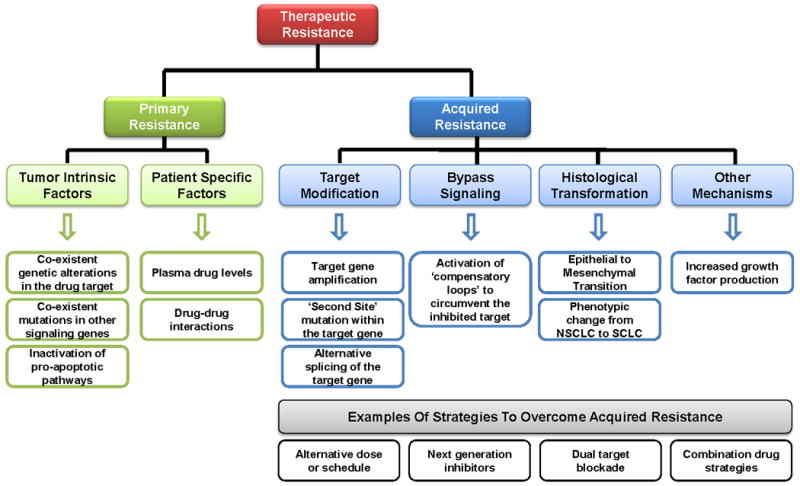

Resistance to targeted therapies can be classified as primary resistance or acquired resistance (Figure 1). Primary resistance is defined as a de novo lack of treatment response. Conversely, acquired resistance refers to disease progression after an initial response to therapy. Importantly, acquired resistance occurs while the patient is still receiving the targeted therapy, implying that the tumor has developed an ‘escape’ mechanism to evade continuous blockade of the target. Specific clinical criteria have been developed for formally defining acquired resistance to EGFR TKIs in EGFR mutant NSCLC (8) and ABL TKIs in CML (9).

Figure 1. Mechanisms of Therapeutic Resistance to Kinase Inhibitors.

Resistance to targeted therapies can be classified as primary resistance or acquired resistance. Primary resistance is defined as a de novo lack of treatment response and can be mediated by tumor intrinsic factors, such as concurrent genetic alterations within the drug target or within other signaling molecules, and by patient specific factors, such as drug-drug interactions. Conversely, acquired resistance refers to disease progression after an initial response to the targeted therapy. Acquired resistance develops while the patient is still receiving the targeted therapy, implying that the tumor has developed an ‘escape’ mechanism to evade continuous blockade of the target. These ‘escape’ mechanisms include target modification (gene amplification, second site mutations, splice variants), the emergence of bypass signaling tracks, histological transformation, as well as other less well characterized mechanisms such as increased growth factor production. Examples of strategies to overcome acquired resistance, which are discussed in more detail within the text, include alternative doses or schedules of the targeted inhibitor, development of more potent ‘next generation’ inhibitors, dual blockade of the initial target with two or more target-specific agents, and combination drug strategies designed to suppress compensatory signaling loops.

Primary Resistance

Clinical and molecular mechanisms leading to primary (de novo) resistance may be broadly categorized as tumor intrinsic factors or patient/drug specific factors. It is worth noting that true primary resistance to a targeted inhibitor in a molecularly defined patient population is relatively uncommon. Technical issues in the identification of the molecular marker as well as compliance of the patient to the prescribed therapy are also important considerations when evaluating for primary resistance.

Tumor Intrinsic Factors

Factors leading to tumor intrinsic primary resistance include the specific target mutation as well as co-existent genetic alterations in either the target gene itself or in other signaling genes. For example, lung tumors with EGFR exon 20 insertions, which account for approximately 4% of EGFR mutations, are associated with a lack of response to clinically achievable doses of the EGFR TKIs, erlotinib and gefitinib (10). In addition, a small percent of patients with EGFR mutant lung cancer harbor both a somatic EGFR activating mutation as well as a germline T790M mutation. Typically associated with acquired resistance to EGFR TKIs, the T790M alteration is found as a heterozygous germline variant in 0.5% of never-smokers with lung adenocarcinoma and has been associated with primary resistance to EGFR TKI therapy (11). Analogously, patients with GIST harboring KIT exon 9 mutations typically display reduced responses to standard doses of imatinib compared to patients with GIST harboring KIT exon 11 mutations (6).

Primary resistance may also result from co-existent alterations within other signaling genes. For example, de novo MET amplification is associated with primary resistance to EGFR TKIs in EGFR mutant NSCLC (12). In addition, drug resistance through inactivation of pro-apoptotic pathways has also been described. Polymorphisms in the pro-apoptotic BIM gene have been shown to result in intrinsic resistance to EGFR TKIs in EGFR mutant NSCLC as well as in imatinib resistance in CML (13).

Patient/Drug Specific Factors

Drug levels and kinetics of drug exposure are affected by several patient specific pharmacokinetic factors, including absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion (ADME). ADME properties may influence the efficacy of targeted therapies in clinical use and result in primary drug resistance. For example, imatinib drug levels correlate with response to therapy (14), however, several studies have shown significant variability of imatinib plasma levels among patients with CML receiving this inhibitor (15). In addition, drug-drug interactions may influence drug levels. For example, it has been reported that co-administration of erlotinib with fenofibrate results in lower plasma levels of erlotinib since fenofibrate induces cytochrome P450 3A4 (CYP3A4), which is involved in the metabolism of erlotinib (16). Finally, drug levels may be affected by inter-individual differences in drug absorption and metabolism.

Acquired Resistance

Acquired resistance to a kinase inhibitor after an initial response develops in most patients. Acquired resistance is a complex and diverse phenomenon, but the end result for each potential mechanism is continued signaling through downstream pathways, despite the continued presence of the inhibitor. Here, we will focus on clinically relevant mechanisms of acquired resistance.

Target modification

Alterations in the target oncogene, including gene amplification and second site mutations, have been described as mechanisms of acquired resistance to many different kinase inhibitors. For example, amplification of EGFR, BCR-ABL, and EML4-ALK have been described in cases of acquired resistance to erlotinib/gefitinib, imatinib, and crizotinib, respectively (17-19). Amplification of the target may mediate drug resistance by shifting the equilibrium in favor of the kinase, resulting in an ‘out-competition’ of the drug. Second site mutations within the target oncogene have also been described for BCR-ABL in CML (20) and EML4-ALK (19, 21), EGFR (22, 23) and ROS1 (24) in NSCLC. In the case of EGFR, the T790M ‘gatekeeper’ mutation is the most common target-specific alteration identified in approximately 50% of patients with acquired resistance to the EGFR TKIs, erlotinib and gefitinib (22, 23). Mutation of the EGFR T790 residue, which is located in the ATP binding cleft of the kinase domain, has been shown to confer drug resistance by increasing the kinase's ATP affinity (25). In contrast, multiple different ‘second site’ mutations which confer reduced drug sensitivity in vitro and in vivo have been described for both BCR-ABL and EML4-ALK (18, 19, 21). These mutations seem to span the entire kinase domain of the respective targets and confer variable levels of drug resistance. More specifically, for EML4-ALK, the mutations appear to cluster around the ATP binding pocket, and molecular modeling studies have demonstrated that the presence of the various ALK kinase domain mutations found at the time of resistance (L1196M, G1269A, G1202R, S1206Y, 1151Tins, and C1156Y) result in diminished crizotinib binding due to steric interference (19, 21). Mutations analogous to the EGFR gatekeeper T790M mutation have also been detected in patient samples at the time of resistance to imatinib and crizotinib (ABL T315I and ALK L1196M, respectively).

It is worth noting that although second site mutations have been described as important mechanisms of acquired resistance to inhibitors of tyrosine kinases, such as EGFR, ALK, and ABL, no such second site mutations have been described in BRAF mutant melanoma tumors with acquired resistance to the BRAF inhibitor, vemurafenib. Interestingly, however, BRAF splice variants which lack the RAS binding domain were found in 6 of 19 vemurafenib-resistant tumor biopsy samples (26). This BRAF splice variant leads to enhanced dimerization of RAF and therefore increased downstream signaling.

Bypass of drug inhibition

Oncogenic kinases share many common downstream signaling mediators, thereby potentially providing a mechanism whereby tumors can bypass dependency on a given ‘driver’ alteration. The presence of a targeted kinase inhibitor provides a selective pressure to circumvent the inhibited kinase and thereby continue signaling through critical downstream pathways to promote sustained tumor proliferation even in the continued presence of the inhibitor. To date, such ‘bypass tracks’ have been most extensively characterized in the context of EGFR mutant and ALK+ NSCLC. In the case of EGFR mutant NSCLC, amplification of the MET receptor tyrosine kinase is detected in approximately 5% of tumors with acquired resistance to EGFR TKI therapy (17). MET amplification has been demonstrated to confer resistance by driving ERBB3-mediated activation of downstream PI3K-AKT signaling (27). In addition, HER2 amplification has been detected in 12% of tumors with acquired resistance to EGFR TKI therapy (28), resulting in sustained downstream signaling, even in the continued presence of the EGFR TKI.

Analogously, in patients with crizotinib-resistant ALK+ NSCLC, EGFR activation has been detected in 4/9 (44%) of tumor biopsy samples at the time of resistance (19). In this case, EGFR activation was evidenced not by mutation or gene amplification, but rather by increased EGFR phosphorylation in the post-crizotinib compared to the pre-crizotinib tumor biopsy samples. In addition, KIT amplification was identified in 2/13 (15%) of patients with crizotinib resistance. These data suggest that either EGFR or KIT may serve as clinically relevant bypass tracks to compensate for ALK inhibition.

Bypass signaling has also been documented as a potential mechanism of resistance to the BRAF inhibitor vemurafenib in BRAF mutant melanoma. Increased expression and phosphorylation of PDGFRβ was found in 4/11 post-vemurafenib biopsy samples (29). In addition, increased IGF-1R phosphorylation has also been documented in post-vemurafenib tumor biopsy samples (30). Similar to bypass tracks activated in EGFR mutant and ALK-rearranged NSCLC, RAF inhibitor resistance mediated by altered receptor tyrosine kinase expression or activity, such as PDGFRβ and IGF-1R, is thought to be conferred by parallel activation of downstream signaling pathways which bypass the inhibited target. In addition, resistance to BRAF inhibitors may also be mediated through activation of other intracellular signaling molecules in the MAP kinase pathway. For example, alterations in MEK1 and NRAS have been found in tumor re-biopsy samples at the time of acquired resistance to vemurafenib (29, 31).

Histological transformation

Changes in tumor histology have been documented at the time of acquired resistance to EGFR TKIs. These histologic changes include epithelial to mesenchymal transformation as well as transformation to small cell (neuroendocrine) histology (17). In particular, transformation to small cell histology was documented in 5/37 (14%) of patients with EGFR mutant lung cancer who developed acquired resistance to EGFR TKI therapy. Notably, all of the patients examined had adenocarcinoma histology in their pre-EGFR TKI tumor biopsy samples, all retained the original EGFR activating mutation, and some patients also had concurrent PIK3CA mutations in the context of the histological transformation.

Other mechanisms of acquired resistance

Though alterations in the target oncogene, bypass signaling, and histological transformation remain the most well characterized resistance mechanisms, other potential means whereby tumor cells can evade the anti-proliferative effects of targeted inhibitors have been described. For example, MET activation through increased production of hepatocyte growth factor (HGF), the ligand for MET, has been described as a mechanism of resistance to EGFR TKIs (32). The frequency of increased HGF production in patient tumor samples remains uncertain. Increased stromal levels of HGF have also been described in vemurafenib-resistant BRAF mutant tumors (33). Additional mechanisms of acquired resistance certainly exist and remain to be characterized on a molecular level. To emphasize this point, consider the case of ‘next generation’ ALK inhibitors. These more potent inhibitors, described below, salvage almost all patients with acquired resistance to crizotinib, yet, only a minority of patients have target gene alteration as the defined mechanism of resistance. These data underscore the critical need to obtain rebiopsies at the time of disease progression to further understand the complexities of therapeutic resistance.

Clinical-Translational Advances

Pre-clinical and clinical studies which have uncovered mechanisms of therapeutic resistance, as described above, have provided crucial information necessary to inform physicians regarding potential therapeutic strategies to attempt to delay or overcome drug resistance.

Strategies to overcome resistance mediated by target modification

Several clinical approaches to overcome resistance are directed at the initial drug target itself. The rationale for these approaches is based on the fact that some oncogene-driven malignancies retain ‘addiction’ to the initial therapeutic target even at the time of resistance. In these cases, resistance is driven by alteration of the target oncogene by either amplification or second site mutation, as described above.

(1) Alternative Doses and Schedules

Dose escalation of imatinib has been demonstrated to be an efficacious strategy in patients with both CML and GIST (34, 35). In EGFR mutant NSCLC, mathematical modeling experiments have suggested that high-dose pulses combined with low-dose continuous EGFR TKI therapy may delay the development of resistance (36). In addition, retrospective reports have demonstrated that pulsatile erlotinib may control CNS metastases from EGFR mutant lung cancer after failure of standard daily dosing (37). In this case series, 6 of 9 patients (67%) patients with CNS metastases (brain and/or leptomeningeal), that occurred despite conventional dose EGFR TKI, had a partial response to pulsatile high dose erlotinib. In the same series, best response outside the CNS was only evaluable in 5/9 patients (56%) – 3 had stable disease (including 2/3 patients who had a PR in the CNS) and 2 had progressive disease There is also one case report of a patient with ALK+ NSCLC whose intracranial disease responded to high dose crizotinib (38). However, this approach needs to be validated in prospective trials.

(2) Development of new, more potent inhibitors

In the case of resistance mediated by target modification, one potential strategy to overcome resistance is through the development of novel inhibitors with increased potency. These so called ‘next generation’ inhibitors have already proven to be an efficacious strategy in CML. The second-generation TKIs, dasatinib, nilotinib, and bosutinib, are more potent than imatinib and have demonstrated efficacy in patients with imatinib-resistant CML (39-41). Of particular note, ponatinib was specifically developed to overcome the BCR-ABL T315I gatekeeper mutation (analogous to EGFR T790M and ALK L1196M mutations) and has already demonstrated efficacy in this patient population (42).

Analogous strategies are being explored in EGFR mutant and ALK+ lung cancer. Pre-clinical data suggested that ‘second generation’ irreversible EGFR TKIs, such as dacomitinib, neratinib, and afatinib may be able to overcome target intrinsic resistance, including inhibiting the EGFR T790M mutation (43-45). Unfortunately, clinical trials with these ‘second generation’ EGFR TKIs as single agents have been disappointing (46, 47). However, recent Phase I trials of the ‘third generation’ EGFR TKIs, AZD9291 and CO-1686, have demonstrated promising clinical results of these agents in patients with advanced EGFR mutant NSCLC and resistance to erlotinib or gefitinib (48, 49). Both drugs are irreversible inhibitors with higher specificity for mutant EGFR (including T790M) compared to wild-type EGFR. Clinical trials with these agents are ongoing. Finally, next-generation ALK inhibitors are being explored in advanced ALK+ NSCLC. These inhibitors are more potent against ALK than crizotinib and overcome many of the known secondary resistance mutations within ALK. Initial results from phase I trials of the ‘second generation’ ALK TKIs, ceritinib (LDK378), alectinib (CH5424802), and AP26113 have demonstrated that all of these agents have efficacy in the setting of crizotinib resistance (50-52), including in the CNS.

(3) Dual target blockade

Analogous to the use of trastuzumab plus lapatinib (53) or trastuzumab plus pertuzumab (7) in HER2+breast cancer, dual target inhibition has been attempted as a strategy in EGFR mutant NSCLC. The combination of the EGFR antibody, cetuximab, plus afatinib has been studied in patients with acquired resistance to erlotinib (54). In the initial phase I study of this combination, the confirmed overall response rate was 40%, similar in both T790M positive and negative tumors. Adverse events including rash and diarrhea, predominantly grade 1/2, were seen in the majority of patients. Further studies are ongoing with this combination.

Drug Combination Strategies

Drug combination therapies are being implemented clinically to both delay the emergence of resistance and to improve therapeutic efficacy. The ability of drug combinations to improve treatment outcomes has been successful in overcoming resistance in other areas of medicine, particularly in antibiotic resistance and HIV infection, and analogous strategies are currently being investigated in cancer medicine. Here we will review strategies for rational anticancer drug combinations.

(1) Targeting of bypass tracks

Strategies aimed at co-targeting bypass tracks are being actively pursued in a number of malignancies. Such strategies are typically devised to provide continuous inhibition of the primary oncogene (the ‘driver’) while also co-inhibiting compensatory signaling loops, with the rational that therapeutic sensitivity can be restored when the two agents are given in combination. For example, combined inhibition of both EGFR and MET has been employed in EGFR mutant NSCLC with acquired resistance mediated by MET amplification (55). There are several MET pathway inhibitors in clinical development, including TKIs (crizotinib, cabozantinib, tivantinib, foretinib) as well as monoclonal antibodies directed against both MET (onartuzumab) and against the HGF ligand (rilotumumab, ficlatuzumab). In addition, the combination of RAF inhibitors with MEK inhibitors has already proven to be an efficacious treatment strategy for patients with BRAF mutant melanoma (56). In a phase I/II study of the combination of the BRAF inhibitor, dabrafenib, with the MEK inhibitor, trametinib, in patients with advanced BRAF mutant melanoma, median progression-free survival was 9.4 months in the combination group versus 5.8 months in the monotherapy group (hazard ratio for progression or death, 0.39; 95% confidence interval, 0.25 to 0.62; p<0.001).

(2) Other rational drug combination strategies

In addition to co-targeting of potential bypass tracks, several other potential therapeutic strategies have been proposed to delay or overcome acquired resistance. One approach involves co-targeting the molecular chaperone, heat shock protein 90 (HSP90) together with the primary oncogene. Many oncogenic kinases are HSP90 clients, and this chaperone is necessary for protein folding and stabilization. Single agent activity of HSP90 inhibitors has been documented in patients with both TKI resistant EGFR mutant (57) and TKI resistant ALK+ NSCLC (58). Numerous on-going clinical trials are evaluating the efficacy of HSP90 inhibitors alone or in combination with kinase inhibitors.

Another potential strategy which has garnered much attention recently is the combination of targeted inhibitors plus immune therapy. Particularly in melanoma, the cancer subtype in which immune based therapies have been most commonly used, there is growing data to suggest that treatment with a BRAF inhibitor results in both increased melanoma antigen expression and tumor recognition by antigen-specific T lymphocytes (59, 60). These data provide the rationale for combining BRAF inhibitors with immune-based therapies. Clinical trials of vemurafenib plus immune checkpoint inhibitors are on-going in melanoma.

Conclusions

The development and clinical application of targeted inhibitors has led to a paradigm shift in the treatment of cancer patients. However, the emergence of resistance is inevitable and represents a critical issue. Despite the wealth of information which has already been obtained about resistance to targeted therapies, several questions remain to be answered, including – (1) How do we address heterogeneity of resistance mechanisms at different sites (or even the same site) within an individual patient? (2) How do we develop and implement clinical trials to take into consideration the rapid pace of scientific discovery and the need to quickly and efficiently bring more efficacious treatments to the forefront of care while limiting the number of patients who receive potentially less effective treatments? (3) How do we gain increased access to tumor biopsy samples at the time of resistance to each line of therapy to be able to more fully understand the dynamics of resistance mechanisms? Moving forward, it is incumbent on physicians and translational scientists to identify gaps in knowledge of therapeutic resistance and to implement strategies to address these gaps. We will need better/more extensive systems for studying resistance, such as the development of non-invasive ways to identify resistant tumor subclones. Overall, a better understanding of resistance mechanisms to targeted therapies will allow us to develop more efficacious therapeutic strategies and improve the care of cancer patients.

Acknowledgments

Funding Sources: CML: K12 CA 0906525 and Damon Runyon Clinical Investigator Award. ATS: R01: 5R01CA164273-03.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: CML has served as a consultant for Pfizer and has been an invited speaker for Abbott Molecular and Qiagen. ATS has served as a consultant for Pfizer, Novartis, Ariad, and Genentech.

References

- 1.Druker BJ, Talpaz M, Resta DJ, Peng B, Buchdunger E, Ford JM, et al. Efficacy and safety of a specific inhibitor of the BCR-ABL tyrosine kinase in chronic myeloid leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2001;344:1031–7. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200104053441401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mok TS, Wu YL, Thongprasert S, Yang CH, Chu DT, Saijo N, et al. Gefitinib or carboplatin-paclitaxel in pulmonary adenocarcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:947–57. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0810699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kwak EL, Bang YJ, Camidge DR, Shaw AT, Solomon B, Maki RG, et al. Anaplastic lymphoma kinase inhibition in non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:1693–703. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1006448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shaw AT, Camidge DR, Engelman JA, Solomon BJ, Kwak EL, Clark JW, Salgia R, Shapiro G, Bang YJ, Tan W, Tye L, Wilner KD, Stephenson P, Varella-Garcia M, Bergethon K, Iafrate AJ, Ou SHI. Clinical activity of crizotinib in advanced non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) harboring ROS1 gene rearrangement. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:2012. suppl; abstr 7508. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Flaherty KT, Puzanov I, Kim KB, Ribas A, McArthur GA, Sosman JA, et al. Inhibition of mutated, activated BRAF in metastatic melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:809–19. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1002011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Heinrich MC, Corless CL, Demetri GD, Blanke CD, von Mehren M, Joensuu H, et al. Kinase mutations and imatinib response in patients with metastatic gastrointestinal stromal tumor. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:4342–9. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.04.190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Baselga J, Cortes J, Kim SB, Im SA, Hegg R, Im YH, et al. Pertuzumab plus trastuzumab plus docetaxel for metastatic breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:109–19. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1113216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jackman D, Pao W, Riely GJ, Engelman JA, Kris MG, Janne PA, et al. Clinical definition of acquired resistance to epidermal growth factor receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitors in non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:357–60. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.24.7049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Baccarani M, Cortes J, Pane F, Niederwieser D, Saglio G, Apperley J, et al. Chronic myeloid leukemia: an update of concepts and management recommendations of European LeukemiaNet. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:6041–51. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.25.0779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Oxnard GR, Lo PC, Nishino M, Dahlberg SE, Lindeman NI, Butaney M, et al. Natural history and molecular characteristics of lung cancers harboring EGFR exon 20 insertions. J Thorac Oncol. 2013;8:179–84. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e3182779d18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Girard N, Lou E, Azzoli CG, Reddy R, Robson M, Harlan M, et al. Analysis of genetic variants in never-smokers with lung cancer facilitated by an Internet-based blood collection protocol: a preliminary report. Clin Cancer Res. 16:755–63. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-2437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cappuzzo F, Janne PA, Skokan M, Finocchiaro G, Rossi E, Ligorio C, et al. MET increased gene copy number and primary resistance to gefitinib therapy in non-small-cell lung cancer patients. Ann Oncol. 2009;20:298–304. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdn635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ng KP, Hillmer AM, Chuah CT, Juan WC, Ko TK, Teo AS, et al. A common BIM deletion polymorphism mediates intrinsic resistance and inferior responses to tyrosine kinase inhibitors in cancer. Nat Med. 2012;18:521–8. doi: 10.1038/nm.2713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Larson RA, Druker BJ, Guilhot F, O'Brien SG, Riviere GJ, Krahnke T, et al. Imatinib pharmacokinetics and its correlation with response and safety in chronic-phase chronic myeloid leukemia: a subanalysis of the IRIS study. Blood. 2008;111:4022–8. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-10-116475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Peng B, Hayes M, Resta D, Racine-Poon A, Druker BJ, Talpaz M, et al. Pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of imatinib in a phase I trial with chronic myeloid leukemia patients. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:935–42. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.03.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mir O, Blanchet B, Goldwasser F. Drug-induced effects on erlotinib metabolism. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:379–80. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc1105083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sequist LV, Waltman BA, Dias-Santagata D, Digumarthy S, Turke AB, Fidias P, et al. Genotypic and histological evolution of lung cancers acquiring resistance to EGFR inhibitors. Sci Transl Med. 2011;3:75ra26. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3002003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shah NP, Sawyers CL. Mechanisms of resistance to STI571 in Philadelphia chromosome-associated leukemias. Oncogene. 2003;22:7389–95. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1206942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Katayama R, Shaw AT, Khan TM, Mino-Kenudson M, Solomon BJ, Halmos B, et al. Mechanisms of acquired crizotinib resistance in ALK-rearranged lung Cancers. Sci Transl Med. 2012;4:120ra17. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3003316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Soverini S, Hochhaus A, Nicolini FE, Gruber F, Lange T, Saglio G, et al. BCR-ABL kinase domain mutation analysis in chronic myeloid leukemia patients treated with tyrosine kinase inhibitors: recommendations from an expert panel on behalf of European LeukemiaNet. Blood. 2011;118:1208–15. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-12-326405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Doebele RC, Pilling AB, Aisner D, Kutateladze TG, Le AT, Weickhardt AJ, et al. Mechanisms of Resistance to Crizotinib in Patients with ALK Gene Rearranged Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2012 doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-11-2906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kobayashi S, Boggon TJ, Dayaram T, Janne PA, Kocher O, Meyerson M, et al. EGFR mutation and resistance of non-small-cell lung cancer to gefitinib. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:786–92. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa044238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pao W, Miller VA, Politi KA, Riely GJ, Somwar R, Zakowski MF, et al. Acquired resistance of lung adenocarcinomas to gefitinib or erlotinib is associated with a second mutation in the EGFR kinase domain. PLoS Med. 2005;2:e73. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0020073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Awad MM, Engelman JA, Shaw AT. Acquired resistance to crizotinib from a mutation in CD74-ROS1. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:1173. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc1309091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yun CH, Mengwasser KE, Toms AV, Woo MS, Greulich H, Wong KK, et al. The T790M mutation in EGFR kinase causes drug resistance by increasing the affinity for ATP. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:2070–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0709662105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Poulikakos PI, Persaud Y, Janakiraman M, Kong X, Ng C, Moriceau G, et al. RAF inhibitor resistance is mediated by dimerization of aberrantly spliced BRAF(V600E) Nature. 2011;480:387–90. doi: 10.1038/nature10662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Engelman JA, Zejnullahu K, Mitsudomi T, Song Y, Hyland C, Park JO, et al. MET amplification leads to gefitinib resistance in lung cancer by activating ERBB3 signaling. Science. 2007;316:1039–43. doi: 10.1126/science.1141478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Takezawa K, Pirazzoli V, Arcila ME, Nebhan CA, Song X, de Stanchina E, et al. HER2 amplification: a potential mechanism of acquired resistance to EGFR inhibition in EGFR-mutant lung cancers that lack the second-site EGFRT790M mutation. Cancer Discov. 2012;2:922–33. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-12-0108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nazarian R, Shi H, Wang Q, Kong X, Koya RC, Lee H, et al. Melanomas acquire resistance to B-RAF(V600E) inhibition by RTK or N-RAS upregulation. Nature. 2010;468:973–7. doi: 10.1038/nature09626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Villanueva J, Vultur A, Lee JT, Somasundaram R, Fukunaga-Kalabis M, Cipolla AK, et al. Acquired resistance to BRAF inhibitors mediated by a RAF kinase switch in melanoma can be overcome by cotargeting MEK and IGF-1R/PI3K. Cancer Cell. 2010;18:683–95. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2010.11.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wagle N, Emery C, Berger MF, Davis MJ, Sawyer A, Pochanard P, et al. Dissecting therapeutic resistance to RAF inhibition in melanoma by tumor genomic profiling. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:3085–96. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.33.2312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yano S, Wang W, Li Q, Matsumoto K, Sakurama H, Nakamura T, et al. Hepatocyte growth factor induces gefitinib resistance of lung adenocarcinoma with epidermal growth factor receptor-activating mutations. Cancer Res. 2008;68:9479–87. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-1643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Straussman R, Morikawa T, Shee K, Barzily-Rokni M, Qian ZR, Du J, et al. Tumour micro-environment elicits innate resistance to RAF inhibitors through HGF secretion. Nature. 2012;487:500–4. doi: 10.1038/nature11183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kantarjian HM, Talpaz M, O'Brien S, Giles F, Garcia-Manero G, Faderl S, et al. Dose escalation of imatinib mesylate can overcome resistance to standard-dose therapy in patients with chronic myelogenous leukemia. Blood. 2003;101:473–5. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-05-1451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Blanke CD, Rankin C, Demetri GD, Ryan CW, von Mehren M, Benjamin RS, et al. Phase III randomized, intergroup trial assessing imatinib mesylate at two dose levels in patients with unresectable or metastatic gastrointestinal stromal tumors expressing the kit receptor tyrosine kinase: S0033. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:626–32. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.13.4452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Foo J, Chmielecki J, Pao W, Michor F. Effects of pharmacokinetic processes and varied dosing schedules on the dynamics of acquired resistance to erlotinib in EGFR-mutant lung cancer. J Thorac Oncol. 2012;7:1583–93. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e31826146ee. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Grommes C, Oxnard GR, Kris MG, Miller VA, Pao W, Holodny AI, et al. “Pulsatile” high-dose weekly erlotinib for CNS metastases from EGFR mutant non-small cell lung cancer. Neuro-oncology. 2011;13:1364–9. doi: 10.1093/neuonc/nor121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kim YH, Ozasa H, Nagai H, Sakamori Y, Yoshida H, Yagi Y, et al. High-dose crizotinib for brain metastases refractory to standard-dose crizotinib. J Thorac Oncol. 2013;8:e85–6. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e31829cebbb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Talpaz M, Shah NP, Kantarjian H, Donato N, Nicoll J, Paquette R, et al. Dasatinib in imatinib-resistant Philadelphia chromosome-positive leukemias. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:2531–41. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa055229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kantarjian H, Giles F, Wunderle L, Bhalla K, O'Brien S, Wassmann B, et al. Nilotinib in imatinib-resistant CML and Philadelphia chromosome-positive ALL. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:2542–51. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa055104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cortes JE, Kantarjian HM, Brummendorf TH, Kim DW, Turkina AG, Shen ZX, et al. Safety and efficacy of bosutinib (SKI-606) in chronic phase Philadelphia chromosome-positive chronic myeloid leukemia patients with resistance or intolerance to imatinib. Blood. 2011;118:4567–76. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-05-355594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cortes JE, Kantarjian H, Shah NP, Bixby D, Mauro MJ, Flinn I, et al. Ponatinib in refractory Philadelphia chromosome-positive leukemias. N Engl J Med. 2012;367:2075–88. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1205127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Engelman JA, Zejnullahu K, Gale CM, Lifshits E, Gonzales AJ, Shimamura T, et al. PF00299804, an irreversible pan-ERBB inhibitor, is effective in lung cancer models with EGFR and ERBB2 mutations that are resistant to gefitinib. Cancer Res. 2007;67:11924–32. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-1885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kwak EL, Sordella R, Bell DW, Godin-Heymann N, Okimoto RA, Brannigan BW, et al. Irreversible inhibitors of the EGF receptor may circumvent acquired resistance to gefitinib. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:7665–70. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0502860102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Li D, Ambrogio L, Shimamura T, Kubo S, Takahashi M, Chirieac LR, et al. BIBW2992, an irreversible EGFR/HER2 inhibitor highly effective in preclinical lung cancer models. Oncogene. 2008;27:4702–11. doi: 10.1038/onc.2008.109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Miller VA, Hirsh V, Cadranel J, Chen YM, Park K, Kim SW, et al. Afatinib versus placebo for patients with advanced, metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer after failure of erlotinib, gefitinib, or both, and one or two lines of chemotherapy (LUX-Lung 1): a phase 2b/3 randomised trial. Lancet Oncol. 2012;13:528–38. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(12)70087-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sequist LV, Besse B, Lynch TJ, Miller VA, Wong KK, Gitlitz B, et al. Neratinib, an irreversible pan-ErbB receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitor: results of a phase II trial in patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:3076–83. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.27.9414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ranson M, Pao W, Kim DW, Kim SW, Ohe Y, Felip E, Planchard D, Ghiorghiu S, Cantarini M, Jänne PA. Preliminary results from a Phase I study with AZD9291: An irreversible inhibitor of epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) activating and resistance mutations in non small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) The European Cancer Congress. 2013 Abstract # 33. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Soria J, Sequist LV, Gadgeel S, Goldman J, Wakelee H, Varga A, Fidias P, Wozniak AJ, Neal JW, Doebele RC, Garon EB, Jaw-Tsai S, Caunt L, Kaur P, Rolfe L, Allen A, Camidge DR. First-In-Human Evaluation of CO-1686, an Irreversible, Highly, Selective Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitor of Mutations of EGFR (Activating and T790M) Journal of Thoracic Oncology. 2013;8:S1–S1410. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Shaw A, M R, Kim DW, Felip E, Chow LQM, Camidge DR, Tan DSW, Vansteenkiste JF, Sharma S, De Pas T, Wolf J, Katayama R, Lau YYY, Goldwasser M, Boral A, Engelman J. Clinical activity of the ALK inhibitor LDK378 in advanced, ALK-positive NSCLC. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31 suppl; abstr 8010. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Camidge DR, Bazhenova L, Salgia R, Weiss GJ, Langer CJ, Shaw AT, Narasimhan NI, Dorer DJ, Rivera VM, Zhang J, Clackson T, Haluska FG, Gettinger SN. Updated results of a first-in-human dose-finding study of the ALK/EGFR inhibitor AP26113 in patients with advanced malignancies. Journal of Thoracic Oncology. 2013;8 [Google Scholar]

- 52.Gadgeel S, Ou SH, Chiappori AA, Riely G, Lee RM, Garcia L, Sato J, Yokoyama S, Tanaka T, Gandhi L. A Phase I Dose Escalation Study of a new ALK Inhibitor, CH5424802/RO5424802, in ALK+ Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer (NSCLC) Patients Who Have Failed Crizotinib. Journal of Thoracic Oncology. 2013;2 [Google Scholar]

- 53.Blackwell KL, Burstein HJ, Storniolo AM, Rugo HS, Sledge G, Aktan G, et al. Overall survival benefit with lapatinib in combination with trastuzumab for patients with human epidermal growth factor receptor 2-positive metastatic breast cancer: final results from the EGF104900 Study. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:2585–92. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.35.6725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Janjigian YY, Smit EF, Horn L, Groen HJM, Camidge R, Gettinger S, Fu Y, Denis LJ, Miller V, Pao W. Activity of afatinib/cetuximab in patients (pts) with EGFR mutant non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) and acquired resistance (AR) to EGFR inhibitors. ESMO 2012 Abstract 1289. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Xu L, Kikuchi E, Xu C, Ebi H, Ercan D, Cheng KA, et al. Combined EGFR/MET or EGFR/HSP90 inhibition is effective in the treatment of lung cancers codriven by mutant EGFR containing T790M and MET. Cancer Res. 2012;72:3302–11. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-11-3720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Flaherty KT, Infante JR, Daud A, Gonzalez R, Kefford RF, Sosman J, et al. Combined BRAF and MEK inhibition in melanoma with BRAF V600 mutations. N Engl J Med. 2012;367:1694–703. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1210093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Garon EB, Moran T, Barlesi F, Gandhi L, Sequist LV, Kim SW, Groen HJM, Besse B, Smit EF, Kim DW, Akimov M, Avsar E, Bailey S, Felip E, Geffen D. Phase II study of the HSP90 inhibitor AUY922 in patients with previously treated, advanced non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) J Clin Oncol. 2012;30 [Google Scholar]

- 58.Sang J, Acquaviva J, Friedland JC, Smith DL, Sequeira M, Zhang C, et al. Targeted inhibition of the molecular chaperone Hsp90 overcomes ALK inhibitor resistance in non-small cell lung cancer. Cancer Discov. 2013;3:430–43. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-12-0440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Boni A, Cogdill AP, Dang P, Udayakumar D, Njauw CN, Sloss CM, et al. Selective BRAFV600E inhibition enhances T-cell recognition of melanoma without affecting lymphocyte function. Cancer Res. 2010;70:5213–9. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-0118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Frederick DT, Piris A, Cogdill AP, Cooper ZA, Lezcano C, Ferrone CR, et al. BRAF inhibition is associated with enhanced melanoma antigen expression and a more favorable tumor microenvironment in patients with metastatic melanoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2013;19:1225–31. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-12-1630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]