Abstract

Purpose

Estimate the association between breastfeeding ≥24 months and severe early childhood caries (ECC).

Methods

Within a birth cohort (n=715) from low-income families in Porto Alegre, Brazil, the age 38-month prevalence of severe-ECC (≥4 affected tooth surfaces or ≥1 affected maxillary anterior teeth) was compared over breastfeeding duration categories using marginal structural models to account for time-dependent confounding by other feeding habits and child growth. Additional analyses assessed whether daily breastfeeding frequency modified the association of breastfeeding duration and severe-ECC. Multiple imputation and censoring weights were used to address incomplete covariate information and missing outcomes, respectively. Confidence intervals (CI) were estimated using bootstrap re-sampling.

Results

Breastfeeding ≥24 months was associated with the highest adjusted population-average severe-ECC prevalence (0.45, 95% CI: 0.36, 0.54) compared with breastfeeding <6 months (0.22, 95% CI: 0.15, 0.28), 6–11 months (0.38, 95% CI: 0.25, 0.53), or 12–23 months (0.39, 95% CI: 0.20, 0.56). High frequency breastfeeding enhanced the association between long-duration breastfeeding and caries (excess prevalence due to interaction: 0.13, 80% CI: −0.03, 0.30).

Conclusions

In this population, breastfeeding ≥24 months, particularly if frequent, was associated with severe-ECC. Dental health should be one consideration, among many, in evaluating health outcomes associated with breastfeeding ≥24 months.

Keywords: breastfeeding, dental caries, epidemiologic methods, feeding behavior, marginal structural models, prospective studies

Introduction

The World Health Organization (WHO) recommends continued breastfeeding up to age 2 years or beyond [1], and failure to breastfeed is associated with poor health consequences for both mother and child [2,3]. However, the nature of the relationship between dental caries and the age to which children are breastfed remains uncertain. Caries is among the most common diseases worldwide and often goes untreated, particularly in low-resource settings [4–6], with negative quality of life implications [7]. Some laboratory models suggest that human milk can cause caries [8,9], particularly in combination with added sugars [10], while some report no demineralization of tooth material by human milk alone [11]. The epidemiological literature [12] includes studies that support a positive association between long-duration breastfeeding and early childhood caries (ECC) [13–16] and others that do not [17,18].

Breastfeeding timing relative to other feeding habits complicates study of breastfeeding duration and ECC. Early breastfeeding cessation might accelerate the introduction of particular foods [19,20], and the foods consumed early in life likely influence caries development [21–23]. In turn, early-life food experiences might also influence the duration to which a breastfeeding child continues nursing [19]. Regression modeling is problematic in the presence of such time-dependent confounding, in which a variable (e.g. early-life food experiences) can be part of a causal pathway between an earlier aspect of exposure (e.g. early breastfeeding) and the outcome, while simultaneously operating as confounder with respect to a later aspect of exposure (e.g. continued breastfeeding). Marginal structural models (MSMs), in contrast, have been used to make causal inference from observational data in the presence of time-varying covariates [24–28]. Such techniques are particularly relevant for exposures, such as breastfeeding, that cannot be easily assigned as a randomized intervention.

We aimed to estimate the association between long-duration breastfeeding (≥24 months) and severe-ECC (S-ECC) in a birth cohort of urban, low-income Brazilian children. We hypothesized that long-duration breastfeeding is associated with greater caries occurrence. We secondarily hypothesized that the association between long-duration breastfeeding and S-ECC is stronger if daily breastfeeding episodes are more frequent.

Methods

Participants

We followed a birth cohort nested in a cluster-randomized trial in Porto Alegre, Brazil. The community water supply is optimally fluoridated [29], and 52 public healthcare centers provide primary medical services predominantly to low-income residents. A stratified random sample (n=20 health centers) was selected from 31 eligible clinics for participation in the original trial of healthcare worker training [30,31].

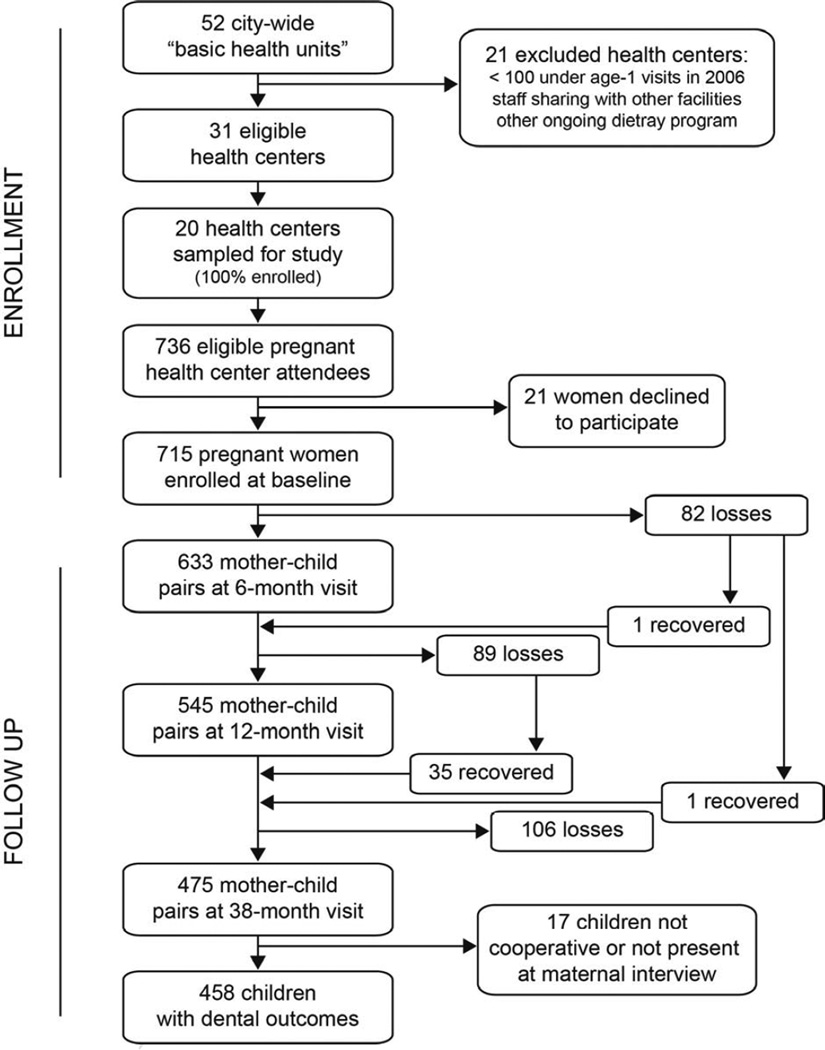

In 2008, 715 of 736 eligible pregnant women with appointments at participating clinics agreed to enroll their children in a cohort to track health outcomes (Figure 1). The trial had provided intervention clinics with healthcare worker training that promoted healthful infant complementary feeding for incorporation into maternal counseling. After 3 years, the intervention did not extend the total duration of breastfeeding (hazard ratio for breastfeeding cessation: 0.94, 95% confidence interval: 0.79, 1.11), although the mean duration of exclusive breastfeeding was increased [30]. S-ECC was not lowered significantly among children born to intervention group clinic attendees [31].

Figure 1. Flow of Participants.

Pregnant women were recruited from 20 municipal health centers in the city of Porto Alegre, Brazil and followed to a mean child age of 38 months.

Baseline variables

Trained fieldworkers collected baseline (during pregnancy) socio-demographic information via structured questionnaires. Data included maternal age, household size, maternal education (≤8 years), maternal smoking (current vs. never/former smoker), indoor bathroom (yes/no), city region (indicators for eight geo-administrative districts), parity (first child yes/no), maternal partner status (married or partnered vs. single, separated, or widowed), household income (≤1500 Brazilian reais monthly; approximately 900 US dollars in 2008), outside income source (e.g. government support), social class (Brazilian Association of Economic Research Institutes classification ≤C), low body mass index (BMI) (≤18, based on measured height and self-reported pre-pregnancy weight). Child sex and birth date were collected at age 5–9 months.

Time-varying behaviors and anthropometry

Infant growth and feeding habits were recorded at each of three home visits, corresponding to mean ages of 6 months (range: 5–9), 12 months (range: 11–15), and 38 months (range: 31–46). Infant length and child height were collected following standard protocol and converted to height/length-for-age Z-scores using WHO standards [32]. At each visit, mothers were asked whether they had ever breastfed and whether they were currently breastfeeding. Breastfeeding duration represented the age to which any breastfeeding continued, regardless of complementary feeding. Breastfeeding mothers were asked how frequently they nursed daily (0, 1, 2–3, or “many times,” separately for day and night). Mothers no longer breastfeeding were asked at what age (in months) breastfeeding ceased.

At the 6-month assessment, the number of feeding bottles consumed in the preceding day was recorded (later categorized 0, 1–3, ≥4). Sugar in the bottle corresponded to consuming ≥1 bottle containing any sweet additive: table sugar, powdered or liquid artificial chocolate, soft drinks, or powdered artificial juice. Questionnaires addressed use of commercially prepared infant formula and the age of introduction of 32 specific foods (e.g. fruits, beans, soft drinks, candies). At the 12-month assessment, the questionnaire posed whether 29 specific items were consumed in the previous month and the weekly consumption frequency of 5 complementary foods (fruits, vegetables, beans, meats, organ meats). Two feeding indices measured dietary patterns to account for foods consumed in combination and to increase the efficiency of the analysis [33]. The indices were created specifically for this analysis due to a lack of existing diet indices specific to cariogenic feeding behaviors in comparable populations. The first, referred to here as the food introduction index, was the count of low nutrient-density and/or presumably cariogenic foods introduced before age 6 months: added sugar, candy, chips, chocolate, chocolate milk, cookies, fruit-flavored drink, gelatin, honey, ice cream, soft drinks, and sweet biscuits. The second, termed here as the first-year feeding index, summed the food introduction index with the count of the following foods recorded at the 12-month assessment: added sugar in a drink, candy, cake, chips, chocolate, chocolate milk, cookies, creamed caramel, fruit-flavored drink, gelatin, honey, ice cream, other confection, soft drinks, and sweet biscuits.

At the 38-month assessment, data were collected regarding bottle use, height-for-age Z-scores, and tooth brushing with fluoride dentifrice. While these variables are likely associated with S-ECC, we did not consider them confounders, because our cut-point for defining the exposure (breastfeeding ≥24 months) temporally preceded these measures. However, we estimated separate models that included these variables as a sensitivity check.

Dental caries

Dental status was evaluated at 38 months following WHO protocol [34], with non-cavitated (white-spot) lesions also recorded. Assessments took place in participants' homes, aided by a lighted intraoral mirror. Teeth were brushed and dried with gauze. Severe-ECC was defined as ≥1 affected maxillary anterior teeth or ≥4 decayed, missing due to caries, or filled tooth surfaces (dmfs ≥4) [35]. Two dentist-examiners completed the evaluations following identical protocol (inter-rater unweighted kappa=0.75; intra-rater unweighted kappa=0.83 for both examiners).

Statistical methods

The proportion of children with S-ECC was compared across four breastfeeding duration categories: <6 months, 6–11 months, 12–23 months, and ≥24 months. Three marginal structural models were fit. The weights for estimating unadjusted models incorporated only clinic allocation status to account for the nested study design. Adjusted models additionally accounted for baseline socio-demographic variables: maternal age, education, parity, pre-pregnancy BMI, smoking status, social class, and child age and sex. Fully-adjusted models included those variables, as well as time-varying bottle use, feeding habits, and length-for-age Z-scores (see below).

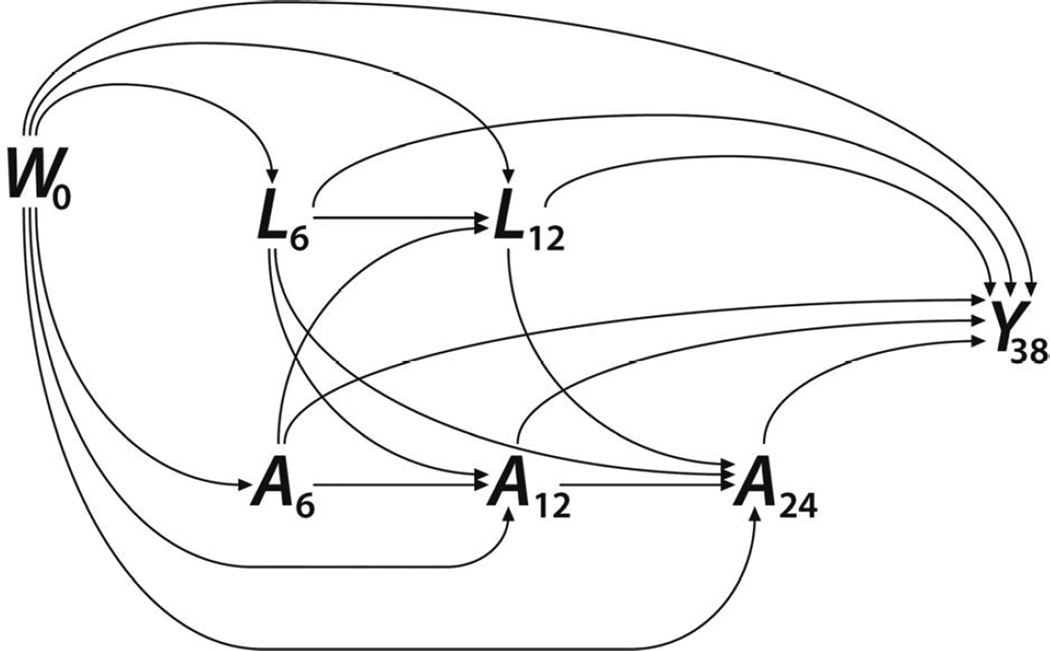

In estimating MSMs, inverse probability weighting was used to generate a “pseudo-population” representative of a hypothetical population in which breastfeeding duration (A) had been allocated independently of confounding variables. Weights were assigned inversely to the predicted probability of observed exposure, given baseline characteristics (W) and longitudinally recorded variables (Lt), giving the greatest weight to observations with exposure and confounder combinations least represented in the sample, relative to what would have been observed under random exposure allocation. Figure 2 depicts the assumed relationships among variables as a directed acyclic graph. Exposure probabilities were estimated using Super Learner, a data-adaptive machine-learning tool [36].

Figure 2. Directed acyclic graph.

The graph depicts the assumed relationships between study variables. W0 = baseline socio-demographic characteristics; At = breastfeeding at time t months; Lt = time-varying feeding behaviors and anthropometry at time t months; Y38 = severe early childhood caries at 38-months. Time-dependent confounding occurs through L12 variables, which are part of a directed path from A6 to Y38 but a back-door path from A24 to Y38.

To account for time-dependent confounding, weights were based on treatment models for three probabilities: the probability of breastfeeding at 6 months (Pr[A6=1]); the probability of breastfeeding at 12 months, given breastfeeding at 6 months (Pr[A12=1 | A6=1]); and the probability of breastfeeding at 24 months, given breastfeeding at 12 months (Pr[A24=1 | A12=1]). Each treatment model was estimated while incorporating temporally appropriate putative confounders: in fully-adjusted models, the 6-month treatment model included clinic allocation status and baseline socio-demographic variables only; the 12-month treatment model included these variables and added the 6-month bottle use variables, formula use, food introduction index, and 6-month length-for-age Z-scores; the 24-month treatment model replaced the food introduction index and 6-month Z-scores with the first-year feeding index and 12-month Z-scores, respectively, and added complementary food frequency. To stabilize the weights, we multiplied by the marginal probability of the observed exposure category [25].

Equation 1 gives the stabilized treatment weights, where indicators (I) take a value of 1 when the exposure category was observed and 0 otherwise.

| (1) |

For each model, missing variables and missing or incomplete breastfeeding histories were multiply imputed from probabilities estimated using Super Learner, corresponding to 2.6% of data among children with observed outcomes. Censoring weights, equal to the inverse probability of having an observed outcome, given exposure and covariates, up-weighted observations most resembling those with missing outcomes. The probability of an observed outcome (Pr[C=0]) was estimated via Super Learner using predictor variables clinic allocation status, maternal age, education, partner status, parity, smoking in pregnancy, and pre-pregnancy BMI, household income, indoor bathroom, number of inhabitants, outside income source, city region, and social class, and child breastfeeding duration, first-year feeding index, height-for-age Z-score, and sex. Stabilized censoring weight numerators were the product of the probability of having outcome data, given breastfeeding duration category, and a 1/0 indicator for having outcome data (equation 2).

| (2) |

Final MSM weights were the product of stabilized treatment weights and stabilized censoring weights: SW = SWT × SWC. In the fully-adjusted model, non-zero stabilized weights had a mean of 0.997 (minimum: 0.28, maximum: 8.90).

For each model, point estimates (prevalence ratio, PR; prevalence difference, PD) were averaged over 200 multiple imputations. Percentile-based 95% confidence intervals (CI) were estimated as the 2.5 and 97.5 quantiles from 5000 bootstrap iterations to account for variance from sampling, imputation, and weighting. For comparison, an analogous complete-case regression analysis was completed using log-linear models and robust variance. Analyses were completed in R version 3.0.1 (http://www.r-project.org).

Secondarily, we examined whether frequent daytime breastfeeding (≥4 daily episodes) intensified the association of breastfeeding duration and S-ECC, restricting the analysis to children breastfed ≥6 months, the earliest age at which frequency data were collected. High frequency daytime breastfeeding and a long duration-high frequency interaction term were included as MSM covariates, and frequent breastfeeding was added to the treatment models. We defined the excess prevalence due to interaction (EPI) as a departure from additivity, following an example proposed for the relative risk [37]. If D and F represent the presence of long-duration and high frequency breastfeeding, respectively, and D̅ and F̅ the absence of these factors, then the EPI = PD(DF) – PD(DF̅) – PD(D̅F). As a sensitivity check, we also estimated models in which frequency strata were defined by high frequency breastfeeding in either the day or night, versus high frequency breastfeeding in neither. Nighttime breastfeeding was not used alone to define strata, because high frequency daytime breastfeeding was common (>50%) when nighttime high frequency breastfeeding was absent. Because tests for statistical interaction may have low power [38], 80% confidence intervals were provided.

Ethics

This study proposal received ethical approval from committees at the Federal University of Health Sciences of Porto Alegre (UFCSPA) and the University of California Berkeley and is in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Informed consent was reached with mothers on behalf of their children. Children with caries or suspected anemia, under-nutrition, or overweight status were referred to their local health center.

Results

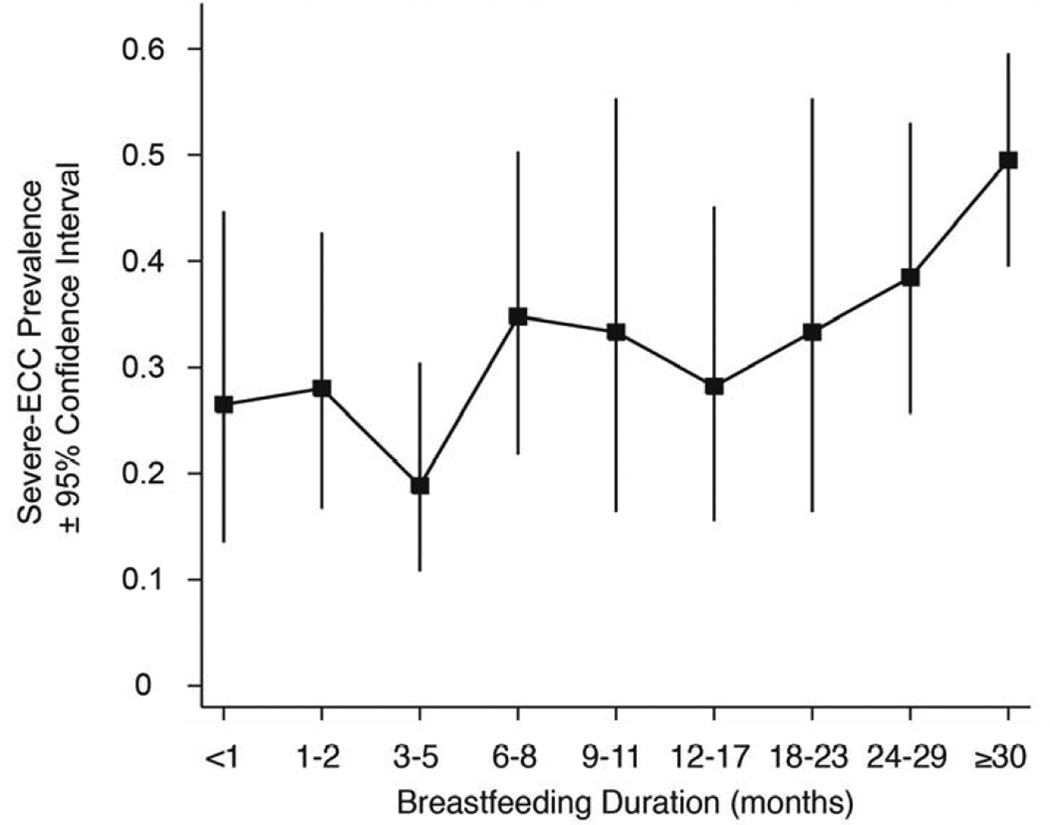

Table 1 demonstrates selected characteristics of the study population. The fraction of mothers interviewed at the 6-month assessment to report initiating any breastfeeding was 0.99 (627/633); the fraction who breastfed to 12 months was 0.47 (282/598). Exclusive breastfeeding continued to mean age 2.1 months. Nearly half the children were introduced to commercially prepared infant formula by 6 months (0.49, 309/632), but few children used formula at 12 months (0.03, 18/539). Bottle use and soft drink consumption were common, while inadequate length-for-age was rare (Table 1). S-ECC prevalence at 38 months was 0.34 (157/458); the prevalence of at least one affected tooth was 0.55 (250/458). Caries was most common among children breastfed for ≥24 months (Figure 3).

Table 1.

Characteristics of Participants

| Characteristic | Number of observations1 |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Socio-demographic characteristics | |||

| Maternal age at expected delivery date, mean (SD), years | 26.0 (6.7) | 715 | |

| Mother has ≤ 8 y of formal education, n (%) | 340 (47.6) | 715 | |

| Household income ≤ 3 times minimum salary2, n (%) | 565 (81.9) | 690 | |

| Social class C or lower by ABIPEME index3, n (%) | 569 (79.8) | 713 | |

| Self-identified maternal race white, n (%) | 395 (55.2) | 715 | |

| Self-identified maternal race black, mixed, or other, n (%) | 320 (44.8) | 715 | |

| Male child, n (%) | 333 (52.4) | 635 | |

| Anthropometry | |||

| Length-for-age Z-score at age 5–9 months, mean (SD) | −0.13 (1.2) | 631 | |

| Length-for-age Z-score <−2 at age 5–9 months, n (%) | 31 (4.9) | 631 | |

| Length-for-age Z-score at age 11–15 months, mean (SD) | −0.03 (0.9) | 527 | |

| Length-for-age Z-score <−2 at age 11–15 months, n (%) | 4 (0.8) | 527 | |

| Feeding Habits | |||

| Introduced to soft drinks before age 6 months, n (%) | 192 (30.3) | 633 | |

| Introduced to any sweets before age 6 months, n (%) | 557 (90.8) | 613 | |

| Consumed soft drinks in prior month at age 11–15 months, n (%) | 413 (76.6) | 539 | |

| Consumed vegetables ≥4 days per week at age 11–15 months, n (%) | 341 (63.5) | 537 | |

| Ever initiated breastfeeding | 627 (98.9) | 633 | |

| Duration exclusive breastfeeding, mean (SD), months | 2.1 (1.6) | 633 | |

| Exclusive breastfeeding to age ≥4 months, n (%) | 152 (24.0) | 633 | |

| Breastfeeding duration to age <6 months, n (%) | 216 (34.1) | 633 | |

| Breastfeeding duration to age 6–11 months, n (%) | 100 (16.7) | 598 | |

| Breastfeeding duration to age 12–23 months, n (%) | 65 (12.1) | 537 | |

| Breastfeeding duration to age ≥24 months, n (%) | 156 (29.1) | 537 | |

| Consuming sweet substances in bottle at age 5–9 months, n (%) | 198 (32.3) | 614 | |

| Consuming sweet substances in bottle at age 2–3 years, n (%) | 312 (68.4) | 456 | |

| Dental Caries Experience at age 2–3 years | |||

| Any affected tooth, n (%) | 250 (54.6) | 458 | |

| S-ECC, n (%) | 157 (34.3) | 458 | |

| dmfs (any decay), mean (SD) | 3.2 (6.1) | 458 | |

| dmfs (cavitated decay only), mean (SD) | 2.6 (5.9) | 458 | |

Abbreviations: SD, standard deviation; ABIPEME, Brazilian Association of Economic Research Institutes; S-ECC, severe early childhood caries; dmfs, decayed missing filled surfaces index

Number of observations differ for some variables due to missing data and/or losses to follow-up

Monthly income of ≤1500 Brazilian reais; approximately 900 US dollars in 2008

Socioeconomic classification scale based on material possessions and education, A = highest status, E = lowest status

Figure 3. Observed Prevalence of Severe Early Childhood Caries at Age 38 Months by Categories of Breastfeeding Duration.

The unadjusted (crude) prevalence of severe early childhood caries by categories of breastfeeding duration is shown for the 439 children with complete observed data for both breastfeeding duration and dental health.

The highest S-ECC prevalence was associated with breastfeeding ≥24 months in all marginal structural models (Table 2). As a sensitivity check, including 38-month variables (bottle use, fluoride toothpaste, height-for-age) in the fully adjusted model did not appreciably alter estimates; for example, the prevalence ratio comparing breastfeeding ≥24 months to <6mo changed to 2.11 (95% CI: 1.50, 3.30) from 2.10 (95% CI: 1.50, 3.25).

Table 2.

Unadjusted and Adjusted Associations of Breastfeeding Duration and Severe Early Childhood Caries in Preschoolers

| Marginal Prevalence1 |

95% CI | Prevalence Ratio |

95% CI | Prevalence Difference |

95% CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Breastfeeding Duration | ||||||

| Unadjusted2 Model | ||||||

| <6 months (reference) | 0.23 | 0.16, 0.30 | 1 | 0 | ||

| 6–11 months | 0.38 | 0.27, 0.50 | 1.66 | 1.06, 2.57 | 0.15 | 0.02, 0.29 |

| 12–23 months | 0.31 | 0.20, 0.43 | 1.35 | 0.81, 2.16 | 0.08 | −0.05, 0.22 |

| ≥24 months | 0.45 | 0.38, 0.53 | 1.98 | 1.44, 2.87 | 0.22 | 0.12, 0.33 |

| Adjusted3 Model | ||||||

| <6 months (reference) | 0.22 | 0.15, 0.28 | 1 | 0 | ||

| 6–11 months | 0.39 | 0.27, 0.53 | 1.79 | 1.13, 2.80 | 0.17 | 0.03, 0.32 |

| 12–23 months | 0.35 | 0.22, 0.49 | 1.59 | 0.97, 2.65 | 0.12 | −0.01, 0.29 |

| ≥24 months | 0.45 | 0.38, 0.53 | 2.06 | 1.51, 3.00 | 0.23 | 0.14, 0.34 |

| Fully-Adjusted4 Model | ||||||

| <6 months (reference) | 0.22 | 0.15, 0.28 | 1 | 0 | ||

| 6–11 months | 0.38 | 0.25, 0.53 | 1.77 | 1.12, 2.85 | 0.17 | 0.03, 0.32 |

| 12–23 months | 0.39 | 0.20, 0.56 | 1.82 | 0.85, 3.20 | 0.18 | −0.03, 0.42 |

| ≥24 months | 0.45 | 0.36, 0.54 | 2.10 | 1.50, 3.25 | 0.24 | 0.13, 0.36 |

Abbreviation: CI, confidence interval

Population-average prevalence of severe early childhood caries at given categories of breastfeeding duration, as estimated from marginal structural models

Includes allocation status from nesting intervention study only

Includes allocation status from nesting intervention study and maternal age, education, parity, pre-pregnancy BMI, smoking status, social class, and child age and sex

Includes all adjusted model variables and time-varying bottle use variables, feeding habits, and height-for-age Z-scores

Compared to breastfeeding 6–23 months, breastfeeding ≥24 months was associated with elevated S-ECC prevalence, although not statistically significant (unadjusted PR: 1.31, 95% CI: 0.97, 1.79; adjusted PR: 1.22, 95% CI: 0.89, 1.66; fully-adjusted PR: 1.17, 95% CI: 0.85, 1.78). However, breastfeeding ≥24 months was more strongly associated with S-ECC when daytime breastfeeding was frequent (fully-adjusted PR: 1.38, 95% CI: 0.97, 2.16) (Table 3). The EPI was 0.13 (80% CI: −0.03, 0.30), suggesting positive interaction between frequent daytime nursing and breastfeeding ≥24 months. Results were similar defining high frequency based on frequent nursing in either the day or night versus neither day or night (fully-adjusted PR with frequent breastfeeding: 1.43, 95% CI: 1.01, 2.18); the EPI increased to 0.23 (80% CI: 0.03, 0.41).

Table 3.

Unadjusted and Adjusted Associations of Breastfeeding ≥24 Months and Severe Early Childhood Caries, Stratified by Frequency of Daytime Breastfeeding

| Marginal Prevalence1 |

95% CI | Prevalence Ratio |

95% CI | EPI | 80% CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Breastfeeding Duration and Frequency | ||||||

| Unadjusted2 Model | ||||||

| Duration 6–23 months and low frequency | 0.38 | 0.25, 0.51 | 1 | |||

| Duration ≥24 months and low frequency | 0.37 | 0.22, 0.52 | 0.97 | 0.53, 1.68 | ||

| Duration 6–23 months and high frequency | 0.31 | 0.22, 0.42 | 1 | |||

| Duration ≥24 months and high frequency | 0.48 | 0.39, 0.57 | 1.53 | 1.06, 2.30 | 0.18 | −0.07, 0.43 |

| Adjusted3 Model | ||||||

| Duration 6–23 months and low frequency | 0.38 | 0.25, 0.51 | 1 | |||

| Duration ≥24 months and low frequency | 0.36 | 0.20, 0.53 | 0.94 | 0.51, 1.67 | ||

| Duration 6–23 months and high frequency | 0.33 | 0.23, 0.44 | 1 | |||

| Duration ≥24 months and high frequency | 0.47 | 0.38, 0.56 | 1.42 | 0.99, 2.12 | 0.16 | −0.10, 0.41 |

| Fully-Adjusted4 Model | ||||||

| Duration 6–23 months and low frequency | 0.36 | 0.24, 0.49 | 1 | |||

| Duration ≥24 months and low frequency | 0.37 | 0.20, 0.55 | 1.01 | 0.52, 1.81 | ||

| Duration 6–23 months and high frequency | 0.35 | 0.23, 0.45 | 1 | |||

| Duration ≥24 months and high frequency | 0.48 | 0.38, 0.58 | 1.38 | 0.97, 2.16 | 0.13 | −0.03, 0.30 |

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; EPI, excess prevalence due to interaction

Population-average prevalence of severe early childhood caries at given categories of breastfeeding duration, as estimated from marginal structural models

Includes allocation status from nesting intervention study only

Includes allocation status from nesting intervention study and maternal age, education, parity, pre-pregnancy BMI, smoking status, social class, and child age and sex

Includes all adjusted model variables and time-varying bottle use variables, feeding habits, and height-for-age Z-scores

Complete-case regression analysis yielded modest differences in estimates (Table 4). However, findings were qualitatively consistent with MSM results, supporting a positive association between S-ECC and breastfeeding ≥24 months.

Table 4.

Unadjusted and Adjusted Associations from Regression Models of Breastfeeding Duration and Severe Early Childhood Caries

| Unadjusted Model n = 439 |

Adjusted Model n = 422 |

Fully Adjusted Model n = 338 |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model Variables | Prevalence Ratio |

95% CI | Prevalence Ratio |

95% CI | Prevalence Ratio |

95% CI |

| Breastfeeding <6 months (reference) | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||

| Breastfeeding 6–11 months | 1.45 | 0.93, 2.23 | 1.52 | 0.99, 2.33 | 1.45 | 0.83, 2.53 |

| Breastfeeding 12–23 months | 1.28 | 0.80, 2.05 | 1.44 | 0.89, 2.32 | 1.39 | 0.73, 2.64 |

| Breastfeeding ≥24 months | 1.96 | 1.40, 2.73 | 2.04 | 1.45, 2.85 | 1.85 | 1.11, 3.08 |

| Clinic allocation (intervention) | 0.85 | 0.65, 1.09 | 0.89 | 0.69, 1.15 | 0.95 | 0.71, 1.27 |

| Maternal age (years) | 0.98 | 0.96, 1.01 | 0.98 | 0.96, 1.01 | ||

| Maternal education (≤8 years) | 1.24 | 0.93, 1.65 | 1.35 | 0.97, 1.89 | ||

| Maternal smoking (current) | 1.49 | 1.13, 1.95 | 1.12 | 0.81, 1.55 | ||

| Parity (has previous child) | 1.18 | 0.85, 1.63 | 1.22 | 0.87, 1.71 | ||

| Social class (C or lower) | 1.09 | 0.77, 1.54 | 1.06 | 0.74, 1.52 | ||

| Pre-pregnancy BMI ≤18 | 1.43 | 1.06, 1.93 | 1.44 | 1.03, 2.01 | ||

| Child age at dental assessment (years) | 1.25 | 0.64, 2.42 | 0.99 | 0.46, 2.12 | ||

| Child sex (male) | 1.18 | 0.91, 1.53 | 1.34 | 1.01, 1.77 | ||

| Length-for-age Zscore at 11–15 months (per SD) | 1.05 | 0.90, 1.23 | ||||

| First-year feeding index (per unit) | 1.05 | 1.01, 1.09 | ||||

| Daily bottles at 5–9 months (1–3) | 0.62 | 0.38, 1.02 | ||||

| Daily bottles at 5–9 months (≥ 4) | 0.84 | 0.47, 1.52 | ||||

| Added sugar in bottle at 5–9 months | 1.46 | 0.94, 2.26 | ||||

| Ever formula fed | 0.82 | 0.59, 1.14 | ||||

| Frequency of fruits at 11–15 months | 0.95 | 0.90, 1.01 | ||||

| Frequency of vegetables at 11–15 months | 1.05 | 0.98, 1.12 | ||||

| Frequency of beans at 11–15 months | 1.02 | 0.94, 1.10 | ||||

| Frequency of meat at 11–15 months | 1.04 | 0.97, 1.12 | ||||

| Frequency of organ meat at 11–15 months | 1.17 | 0.98, 1.39 | ||||

Abbreviation: CI, confidence interval; BMI, body mass index; SD, standard deviation

Discussion

In this population of low-income Brazilian families, we estimated an increase in severe early childhood caries prevalence with breastfeeding 24 months or beyond. While the overall health benefits of breastfeeding are considerable, this work adds evidence that, in some contexts, very extended and frequent breastfeeding might increase caries risk. In addition to exposing teeth to bacterially fermentable milk sugars, prolonged breastfeeding might enhance the fidelity with which caries-causing oral bacteria are transmitted from mothers [39].

Several investigations have reported positive associations between breastfeeding duration and caries when using cut-points exceeding 18 months to define the uppermost duration category [13–15,40,41]. Studies that reported no association between caries and breastfeeding generally used earlier cut-points to define long-duration breastfeeding (i.e. ≥8 or ≥13 months) and have featured populations in which breastfeeding to age 2 years is uncommon, such as in Germany [42], Italy [17], and the United States [18]. A large hospital-based breastfeeding promotion intervention in Belarus did not affect caries prevalence at age 6 years [43]; however, the study did not directly compare caries outcomes among children who were or were not breastfed for extended durations (e.g. ≥24 months), which was an uncommon behavior in that trial population.

Daily breastfeeding frequency was associated with S-ECC in a previous study of Brazilian preschoolers, in which breastfeeding frequency, but not duration ≥12 months, maintained statistical significance in multi-variable models [21]. A combined measure of breastfeeding duration and frequency was strongly associated with ECC in Mayanmar [44], and a measure of nighttime breastfeeding burden, which was based on frequency, was positively associated with ECC in Iran [45], although not statistically significant.

An important strength of this study was the longitudinal, prospective collection of feeding information. We use weighting estimators to respect the temporal sequence of exposure and covariate information, accounting for time-dependent confounding by early-life feeding habits [46]. These methods have not been broadly used in oral health epidemiology.

Causal interpretation of marginal structural model results depends on unverifiable assumptions, specifically, positivity, exchangeability, and correct specification of the treatment models used to generate the weights [25,28]. In this analysis, the distribution of the weights was not extreme, important socioeconomic and nutritional confounders were prospectively collected, and Super Learner estimation reduced the reliance on parametric model-building assumptions [36]. These strengths give credence to causal interpretations, however, as with any observational study, residual confounding cannot be ruled out. For instance, our main estimates do not adjust for earlier oral hygiene habits. However, adjustment for 38-month toothbrushing habits did not affect estimates, and we have no evidence that oral hygiene habits would be associated with breastfeeding duration. Also, while we adjust for the age of introduction and weekly frequency of selected foods, not every aspect of the diet was recorded. Conservatively, we consider our estimates to represent meaningful associations, for which definitive causal claims await confirmation from future studies.

Losses to follow-up were relatively high but not unusual among cohort studies in low-resource settings, where participants frequently change address and contact information. Inverse probability censoring weights can account for losses, and, in this study, weighted estimates were similar to those from complete-case regression. However, losses remain a limitation, as strategies to account for missing data introduce additional assumptions [47]. EPI estimates were imprecise, because a relatively small number of children breastfed both infrequently and to long durations limited the statistical power to confirm interactions. Finally, this study population, featuring a relatively high prevalence of breastfeeding and of caries, might not be representative of the breastfeeding-caries relationship in all historical, geographical, and socioeconomic contexts.

A critical question raised by our findings is why breastfeeding, a normative and otherwise health-promoting human behavior, would be associated with deleterious dental outcomes. One possibility is that the mechanism through which repeated, prolonged exposure to human milk could enhance caries progression might operate differently under the near universal availability of highly refined sugars in the modern diet versus historically. Laboratory studies demonstrating greater cariogenic potential of human milk with the addition of outside sugars support this hypothesis [10,11]. Future research is recommended to better define the relationship between particular breastfeeding practices and dental caries in the context of a high-sugar food supply. Our results in no way suggest that breastfeeding itself be discouraged but are congruent with guidelines from professional dental organizations, which recommend supporting a mother’s decision to breastfeed but avoiding ad libitum breastfeeding after tooth eruption [48].

Acknowledgements

Thank you to Drs. Arthur Reingold and Barbara Abrams of the University of California Berkeley for comments on the manuscript, to members of the Nutrition Research Group (NUPEN) at the Federal University of Health Sciences of Porto Alegre for participant recruitment, data collection, and data management, and to Priscila Humbert Rodrigues of the Universidade Luterana do Brasil for assistance in data collection.

Abbreviations

- BMI

body mass index

- CI

confidence interval

- ECC

early childhood caries

- EPI

excess prevalence due to interaction

- MSM

marginal structural model

- PD

prevalence difference

- PR

prevalence ratio

- S-ECC

severe early childhood caries

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Benjamin W. Chaffee, Department of Preventive and Restorative Dental Sciences, University of California San Francisco, San Francisco, USA, Division of Epidemiology, University of California Berkeley, Berkeley, USA (at the time of the study).

Carlos Alberto Feldens, Department of Pediatric Dentistry, Universidade Luterana do Brasil, Canoas, Brazil.

Márcia Regina Vítolo, Department of Nutrition, Universidade Federal de Ciências da Saúde de Porto Alegre, Porto Alegre, Brazil.

References

- 1.World Health Organization (WHO) Global Strategy for Infant and Young Child Feeding. Geneva: WHO; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US) Breastfeeding and Maternal and Infant Health Outcomes in Developed Countries. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2007. (Evidence Reports/Technology Assessments, no. 153) (AHRQ Publication No. 07-E007) (Contract no. 290-02-0022) [Google Scholar]

- 3.Horta BL, Bahl R, Martines JC, Victora CG. WHO. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2007. Evidence on the long-term effects of breastfeeding: Systematic reviews and meta-analyses. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Marcenes W, Kassebaum NJ, Bernabé E, Flaxman A, Naghavi M, Lopez A, et al. Global burden of oral conditions in 1990–2010: a systematic analysis. J Dent Res. 2013;92(7):592–597. doi: 10.1177/0022034513490168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mouradian WE, Wehr E, Crall JJ. Disparities in children's oral health and access to dental care. JAMA. 2000;284(20):2625–2631. doi: 10.1001/jama.284.20.2625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Selwitz RH, Ismail AI, Pitts NB. Dental caries. Lancet. 2007;369(9555):51–59. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60031-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kramer PF, Feldens CA, Ferreira SH, et al. Exploring the impact of oral diseases and disorders on quality of life of preschool children. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2013;41(4):327–335. doi: 10.1111/cdoe.12035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bowen WH, Lawrence RA. Comparison of the cariogenicity of cola, honey, cow milk, human milk, and sucrose. Pediatrics. 2005;116(4):921–926. doi: 10.1542/peds.2004-2462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Thomson ME, Thomson CW, Chandler NP. In vitro and intra-oral investigations into the cariogenic potential of human milk. Caries Res. 1996;30(6):434–438. doi: 10.1159/000262356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Prabhakar AR, Kurthukoti AJ, Gupta P. Cariogenicity and acidogenicity of human milk, plain and sweetened bovine milk: an in vitro study. J Clin Pediatr Dent. 2010;34(3):239–247. doi: 10.17796/jcpd.34.3.lk08l57045043444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Erickson PR, Mazhari E. Investigation of the role of human breast milk in caries development. Pediatr Dent. 1999;21(2):86–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Valaitis R, Hesch R, Passarelli C, et al. A systematic review of the relationship between breastfeeding and early childhood caries. Can J Public Health. 2000;91(6):411–417. doi: 10.1007/BF03404819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Aida J, Ando Y, Oosaka M, et al. Contributions of social context to inequality in dental caries: a multilevel analysis of Japanese 3-year-old children. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2008;36(2):149–156. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0528.2007.00380.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sakuma S, Nakamura M, Miyazaki H. Predictors of dental caries development in 1.5-year-old high-risk children in the Japanese public health service. J Public Health Dent. 2007;67(1):14–19. doi: 10.1111/j.1752-7325.2007.00003.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tanaka K, Miyake Y. Association between breastfeeding and dental caries in Japanese children. J Epidemiol. 2012;22(1):72–77. doi: 10.2188/jea.JE20110042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhou Y, Lin HC, Lo EC, et al. Risk indicators for early childhood caries in 2-year-old children in southern China. Aust Dent J. 2011;56(1):33–39. doi: 10.1111/j.1834-7819.2010.01280.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Campus G, Solinas G, Strohmenger L, et al. National pathfinder survey on children's oral health in Italy: pattern and severity of caries disease in 4-year-olds. Caries Res. 2009;43(2):155–162. doi: 10.1159/000211719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Iida H, Auinger P, Billings RJ, et al. Association between infant breastfeeding and early childhood caries in the United States. Pediatrics. 2007;120(4):e944–e952. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-0124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Scott JA, Binns CW, Graham KI, et al. Predictors of the early introduction of solid foods in infants: results of a cohort study. BMC Pediatr. 2009;9:E60. doi: 10.1186/1471-2431-9-60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wright CM, Parkinson KN, Drewett RF. Why are babies weaned early? Data from a prospective population based cohort study. Arch Dis Child. 2004;89(9):813–816. doi: 10.1136/adc.2003.038448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Feldens CA, Giugliani ER, Vigo Á, et al. Early feeding practices and severe early childhood caries in four-year-old children from southern Brazil: A birth cohort study. Caries Res. 2010;44(5):445–452. doi: 10.1159/000319898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mobley C, Marshall TA, Milgrom P, et al. The contribution of dietary factors to dental caries and disparities in caries. Acad Pediatr. 2009;9(6):410–414. doi: 10.1016/j.acap.2009.09.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Thitasomakul S, Piwat S, Thearmontree A, et al. Risks for early childhood caries analyzed by negative binomial models. J Dent Res. 2009;88(2):137–141. doi: 10.1177/0022034508328629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cole SR, Hernán MA, Margolick JB, et al. Marginal structural models for estimating the effect of highly active antiretroviral therapy initiation on CD4 cell count. Am J Epidemiol. 2005;162(5):471–478. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwi216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cole SR, Hernán MA. Constructing inverse probability weights for marginal structural models. Am J Epidemiol. 2008;168(6):656–664. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwn164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Garcia-Aymerich J, Lange P, Serra I, Schnohr P, Antó JM. Time-dependent confounding in the study of the effects of regular physical activity in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: an application of the marginal structural model. Ann Epidemiol. 2008;18(10):775–783. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2008.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Robins JM, Hernán MA, Brumback B. Marginal structural models and causal inference in epidemiology. Epidemiology. 2000;11(5):550–560. doi: 10.1097/00001648-200009000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hernán MA, Robins JM. Estimating causal effects from epidemiological data. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2006;60(7):578–586. doi: 10.1136/jech.2004.029496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Municipality of Porto Alegre Department of Water and Sewerage. [Accessed April 12, 2013];Relatórios mensais de qualidade da água. http://www2.portoalegre.rs.gov.br/dmae/default.php?reg=3&p_secao=176.

- 30.Bernardi JR, Gama CM, Vítolo MR. An infant feeding update program at healthcare centers and its impact on breastfeeding and morbidity [in Portuguese] Cad Saude Publica. 2011;27(6):1213–1222. doi: 10.1590/s0102-311x2011000600018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chaffee BW, Feldens CA, Vítolo MR. Cluster-randomized trial of infant nutrition training for caries prevention. J Dent Res. 2013;92(7 Suppl):S29–S36. doi: 10.1177/0022034513484331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.World Health Organization. WHO. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2006. WHO Child Growth Standards:Methods and development:Length/height-for-age, weight-for-age, weight-for-length, weight-for-height and body mass index-for-age. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hu FB. Dietary pattern analysis: a new direction in nutritional epidemiology. Curr Opin Lipidol. 2002;13(1):3–9. doi: 10.1097/00041433-200202000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.World Health Organization. WHO. 4th edition. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 1997. Oral health surveys, basic methods. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Drury TF, Horowitz AM, Ismail AI, et al. Diagnosing and reporting early childhood caries for research purposes. A report of a workshop sponsored by the national institute of dental and craniofacial research, the health resources and services administration, and the health care financing administration. J Public Health Dent. 1999;59(3):192–197. doi: 10.1111/j.1752-7325.1999.tb03268.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.van der Laan MJ, Polley EC, Hubbard AE. Super learner. Stat Appl Genet Mol Biol. 2007;6 doi: 10.2202/1544-6115.1309. Article25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rothman KJ, Greenland S, editors. Modern Epidemiology. 2nd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott-Raven, Publishers; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Greenland S. Tests for interaction in epidemiologic studies: a review and a study of power. Stat Med. 1983;2(2):243–251. doi: 10.1002/sim.4780020219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Li Y, Wang W, Caufield PW. The fidelity of mutans streptococci transmission and caries status correlate with breast-feeding experience among Chinese families. Caries Res. 2000;34(2):123–132. doi: 10.1159/000016579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hallett KB, O'Rourke PK. Early childhood caries and infant feeding practice. Community Dent Health. 2002;19(4):237–242. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jigjid B, Ueno M, Shinada K, et al. Early childhood caries and related risk factors in Mongolian children. Community Dent Health. 2009;26(2):121–128. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pieper K, Dressler S, Heinzel-Gutenbrunner M, et al. The influence of social status on pre-school children's eating habits, caries experience and caries prevention behavior. Int J Public Health. 2012;57(1):207–215. doi: 10.1007/s00038-011-0291-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kramer MS, Vanilovich I, Matush L, et al. The effect of prolonged and exclusive breast-feeding on dental caries in early school-age children. new evidence from a large randomized trial. Caries Res. 2007;41(6):484–488. doi: 10.1159/000108596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.van Palenstein Helderman WH, Soe W, van 't Hof MA. Risk factors of early childhood caries in a Southeast Asian population. J Dent Res. 2006;85(1):85–88. doi: 10.1177/154405910608500115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mohebbi SZ, Virtanen JI, Vahid-Golpayegani M, et al. Feeding habits as determinants of early childhood caries in a population where prolonged breastfeeding is the norm. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2008;36(4):363–369. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0528.2007.00408.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bodnar LM, Davidian M, Siega-Riz AM, et al. Marginal structural models for analyzing causal effects of time-dependent treatments: an application in perinatal epidemiology. Am J Epidemiol. 2004;159:926–934. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwh131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Greenland S, Finkle WD. A critical look at methods for handling missing covariates in epidemiologic regression analyses. Am J Epidemiol. 1995;142(10):1255–1264. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a117592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.American Academy of Pedodontics and the American Academy of Pediatrics. Policy on Early Childhood Caries (ECC): Classifications, Consequences, and Preventive Strategies. Pediatric Dent. 2012;34(6):50–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]