Abstract

Objective

The goal of measuring therapist adherence is to determine if a therapist can perform a given treatment. Yet the evaluation of therapist behaviors in most clinical trials is limited. Typically, randomized trials have few therapists and minimize therapist variability through training and supervision. Furthermore, therapist adherence is confounded with uncontrolled differences in patients across therapists. Consequently, the extent to which adherence measures capture differences in actual therapist adherence versus other sources of variance is unclear.

Method

We estimated intra-class correlations (ICCs) for therapist adherence in sessions with real and standardized patients (RPs and SPs), using ratings from a motivational interviewing (MI) dissemination trial (Baer et al., 2009) in which 189 therapists recorded 826 sessions with both patient types. We also examined the correlations of therapist adherence between SP and RP sessions, and the reliability of therapist level adherence scores with generalizability coefficients (GCs).

Results

ICC’s for therapist adherence were generally large (average ICC for SPs = 0.44, RPs = 0.40), meaning that a given therapist’s adherence scores were quite similar across their sessions. Both ICCs and GCs were larger for SP sessions as compared to RPs on global measures of MI adherence, such as Empathy and MI Spirit. Correlations between therapist adherence with real and standardized patients were moderate to large on three of five adherence measures.

Conclusion

Differences in therapist-level adherence ratings were substantial, and standardized patients have promise as tools to evaluate therapist behavior.

Keywords: Motivational Interviewing, Therapist Adherence, Mixed Models, Standardized Patients

Motivational Interviewing (MI) refers to a class of evidenced based treatments that prescribe a specific therapist linguistic style (e.g., empathy, strategic elicitation of patient “change talk” (Miller & Rollnick, 2013). Given this theoretical focus on the therapists linguistic style, the evaluation of therapist behavior in MI (e.g., adherence; what the therapist says and how they say it) is important – determining the need for training, evaluating dissemination efforts, and investigating the purported mechanisms of MI.

There are several established coding methods are available for evaluating adherence in MI, such as the Motivational Interviewing Treatment Integrity, MITI; Moyers, Martin, & Manuel, 2005). The goal of measures such as the MITI is to determine the degree to which a particular therapist knows and is able to deliver MI faithfully. Here, “adherence” is primarily thought of as a therapist characteristic. However, the performance of these measures in providing information about differences in therapist performance is not well established. Specifically, adherence measures assess what the therapist does during a session, but we do not know if variability in adherence is driven primarily by therapists themselves, or if adherence scores reflect other dyadic processes (e.g., patients may elicit different levels of adherence as some may be more difficult, compliant, etc.). Any such patient effects would add variability in adherence ratings that are not due to the therapist. If measures of adherence are primarily driven by non-therapist factors, their construct validity may be limited.

The current study examines the extent to which therapists are responsible for differences in scores obtained from a commonly used measure of MI adherence using data from a large dissemination trial. Prior to introducing the present study, we consider two issues relevant to the construct validity of therapist adherence from behavioral observations: (a) sources of variability in adherence measures, and (b) the reliability of a given therapist’s adherence score. In addition, we highlight the limitations of data obtained from trials for examining therapist adherence and discuss the use of standardized patients (as opposed to real patients) as an alternative method.

Sources of Variability

An adherence scale is designed to measure the extent to which a therapist performs specific behaviors. While a measure like the MITI is a seemingly straightforward measure of therapist behaviors (e.g., was the therapist utterance an open or closed question), the interpretation of therapist adherence scores is challenging because ratings are influenced by multiple factors. For example, imagine adherence ratings for two therapists, each of whom saw a different client. All other things being equal, the therapist with the higher rating is more adherent. However, this is the problem; the “other things” are almost never equal. Simple conclusions are problematic because adherence ratings are affected by multiple variables, including, but not limited to the therapists’ ‘true’ adherence. Thus, a therapist may receive a lower adherence rating than another therapist or may fall short of a proficiency benchmark for reasons other than his or her ‘true’ adherence.

As therapist behaviors occur within a dyadic interaction, variability in ratings is influenced by: (a) the therapist, (b) the patient, (c) the relationship between patient and therapist (i.e., the dyad), and (d) error (Kenny, Kashy, Cook, & Simpson, 2006). The determination of a therapists’ true adherence score first requires estimating variability in ‘therapist adherence scores’ (therapist adherence), or a therapist’s adherence score after controlling for other sources of variability. Variability in therapist adherence scores can be estimated with mixed effects models (sometimes called multilevel models). Applied to data with patients nested within therapists, mixed effects models will estimate the variability between therapists (e.g., the variability across therapists in typical adherence scores) as well as variability within therapists (i.e., residual error). The intra-class correlation (ICC) is a ratio of the variance among therapists to the total variance and can be used as an index of the influence of therapists on adherence scores.

In an ideal study of provider performance, differences in therapist adherence should be relatively large compared to other sources of variability. This is directly counter to the typical randomized trial, in which therapist variance is minimized in order to maximize internal validity of treatments. Therapists rated low on adherence scales are either (a) not selected for participation, (b) trained to an adequate level of adherence, or (c) removed from the trial. Thus, therapist variability in adherence from randomized trials almost certainly under-represents the true variability in therapist adherence that exists in the community. In addition, given the costs of clinical trials, it is typically not feasible to monitor the performance of a large number of therapists - the average number of therapists in clinical trials is 9.05.1 Even large multi-site trials may only employ 20-30 therapists, a number that is not likely to be sufficient for an adequate test of differences in therapist adherence. Data from naturalistic settings provide much larger therapist samples – the average number of therapists per study is 60.5 – with notably more therapist variability. However, client variability is also likely to be larger than the typical clinical trial – potentially washing out any increased ability to detect true differences among therapists (Baldwin et al., 2013; Wampold & Brown, 2005).

In clinical trials, the variability in adherence ratings due to the contributions of patients (i.e., the variability of adherence scores within therapists case loads) is typically larger than the variability in adherence scores between therapists. For example, Imel et al. (2011) found that patients accounted for as much and sometimes more variability in measures of adherence and competence to Motivational Enhancement Therapy than therapists – with therapists accounting for less than 15% of variability in most measures and as little as 2 percent on some outcomes (see also Boswell et al., 2013; Dennhag, Gibbons, Barber, Gallop, & Crits-Christoph, 2012 and for an exception on one outcome Apodaca, Magill, Longabaugh, Jackson, & Monti, 2013). Researchers must realize that when making inferences about therapist adherence from trials such as these, much of the variability in scores is due to the patient.

In addition, the nested structure of psychotherapy data makes the isolation of differences in therapist adherence difficult. Clinical trials are usually nested in structure - one therapist treats several different patients, but patients receive treatment from only one therapist. As patients often cannot be randomly assigned to therapists, therapist differences may be biased by unmeasured differences in client characteristics across therapist caseloads (e.g., symptom severity). For example, there is evidence a patient’s active substance use is associated with less adherence to MI. Alternatively, patients who were judged to have lower motivation at the beginning of a session had sessions with higher adherence ratings (Imel et al., 2011). Boswell et al. (2013) found that patient interpersonal aggression predicted lower therapist adherence and competence ratings. Round robin designs or ‘non-nested’ (e.g., cross-classified) data, in which multiple therapists treat the same patient, are necessary to control for patient effects and more fully isolate therapist contributions to measures of adherence (Kenny et al., 2006; Marcus, Kashy, & Baldwin, 2009). Unfortunately, this design – which would require the treatment of all patients by all therapists - is typically unfeasible in applied clinical studies with real patients.

Dependability of Therapist Scores

Low therapist variability combined with the high patient variability present in clinical studies presents problems for making reliable judgments about therapists. Specifically, when making judgments about scores on an adherence measure, it is important to determine how many observations are necessary before an accurate judgment can be made about a given therapist. The number of observations required is a function of the measure’s dependability - a concept derived from generalizability theory and related to reliability from classical test theory. As adherence ratings often vary across patients in a caseload, ratings from a single patient interview may provide a biased estimate of a therapist’s ‘true’ adherence score. A generalizability coefficient provides an index of dependability and refers to the percentage of ‘true score’ variance (the extent a therapist’s score provides information about their true score) in a therapist’s adherence rating (Cardinet & Pini, 2009). Higher scores (>.80) indicate that the therapist’s adherence rating contains a higher percentage of true score variance (Webb & Shavelson, 2006). Essentially, a generalizability coefficient indexes the amount of therapist ‘signal’ in a measure and thus the number of observations required to obtain a stable estimate.

The dependability of a particular therapist’s adherence score is also a function of the overall variability due to therapists. As the proportion of total variance in adherence due to therapists increases, dependability of individual therapist scores also increases. Thus, therapist dependability is closely tied to the intra-class correlation (ICC) noted above. The larger the ICC, the smaller number of observations required to achieve a dependable score (Baldwin, Imel, & Atkins, 2012). Low therapist ICCs require many observations per therapist to achieve adequate generalizability coefficient for therapists (e.g., n = 54-70: Crits-Christoph, Gibbons, Hamilton, Ring-Kurtz, & Gallop, 2011, n = 18-70; Dennhag et al., 2012).

In sum, clinical research typically includes nested data with small therapist samples, small differences among therapists, and large variability among clients within therapist caseloads. When differences in therapist adherence are small, observed variability in scores cannot be directly attributed to therapist and a prohibitively large number of observations per therapist would be required to obtain reliable therapist adherence estimates. If differences in therapist adherence are truly small (and not an artifact of selection), the construct validity of the adherence measure is questionable – suggesting that the measure is actually tapping into other processes besides therapists’ tendency to perform the treatment.

Dissemination Studies and Standardized Patients

Dissemination and training studies may provide a compliment to the traditional approach of examining therapist adherence in the context of a clinical trial. Dissemination studies focus on the evaluation of therapists – as opposed to therapies, and therapist samples are often much larger (n > 100) than patient focused clinical trials (e.g., Baer et al., 2009; Miller et al., 2004). In addition, there is likely to be less restriction on the skill of therapists included in the study, providing increased statistical power and a greater range of therapist adherence.

In addition, these studies often use standardized patients to evaluate therapists (Baer et al., 2009; Baer et al., 2004; Miller et al., 2004; Miller & Mount, 2001). Medical educators and researchers have long used standardized patients to evaluate physicians and control for differences in the presentation of real patients (Stimmel, Cohen, Fallar, & Smith, 2006). Standardized patients are typically provided a script or case profile and trained to minimize differences in client presentation that could obscure real differences in therapist adherence. In addition to reducing patient variability, the use of several standardized patients to evaluate a large pool of therapists avoids confounds due to non-random assignment of clients to therapists as standardized patients see many if not all therapists.

While dissemination studies represent a method that may accommodate problems related to assessing therapist performance in clinical trials, whether data from these designs provides valid information about therapist performance with real patients remains in question. For example, if the goal of SPs is to provide a standardized method for evaluating MI therapists, the amount of variability in therapist adherence scores should be large (i.e., the expected correlation among observations within a therapists caseload should be larger because of reduced differences in patient adherence). In addition, the validity of observations from SP sessions depends on establishing correlations with ratings obtained from real patients. In a recent study of 91 therapists, correlations between adherence scores with real and standardized patients were small (r = .05 -.27; Decker et al., 2013). If the association between therapist performance with real and standardized patient sessions is truly small, the utility of standardized patients for assessing therapist performance with real patients is questionable.

Current Study

The aim of the current study is to examine the construct validity of a well-known MI adherence measure using data from a large dissemination trial that included both standardized and real patients. We had four hypotheses. First, we hypothesized that the ICC for therapist adherence ratings would be large, with therapists accounting for greater than 20% of the variability in scores (i.e., greater than previous estimates reported in the literature; Hypothesis 1). Second, we expected ICCs would be larger with standardized as compared to real patients (Hypothesis 2). We also expected that ratings of therapist adherence with real and standardized patients would be strongly correlated (r ≥ .40; Hypothesis 3). Finally, we tested generalizability coefficients for each outcome for standardized and real patients. We expected GCs would be smaller for standardized patients sessions as compared to real patient sessions (Hypothesis 4).

Method

Data Source

Data were obtained from a multi-site (6 primary, 2 pilot sites, and an open enrollment cohort) MI training study in which providers were recruited from National Institute of Drug Abuse (NIDA) Clinical Trials Network (CTN) affiliated community substance abuse treatment facilities in the state of Washington (Baer et al., 2009). Therapists were randomized to one of two MI training formats: 1) a two-day workshop, or 2) training that included five, 2.5-3 hour training sessions spaced over eight weeks. In addition to contact with trainers during training sessions, learners in condition two practiced with standardized patients, immediately received feedback from their standardized patients, and then had their audiotapes reviewed by trainers who provided them with brief written feedback. Note that standardized patients used during training were not the same standardized patients used for evaluation of training outcomes, which took place separately and under the full awareness of providers. Each group received approximately 15 total hours of time with MI trainers.

Therapists were evaluated prior to training, post-training, and at 3-month follow-up. At each assessment point therapists were asked to submit one SP and one RP session recording. Thus each therapist participant provided up to six, 20-minute long sessions conducted with SPs and RPs. Results showed a significant effect of training with therapist MI skills increasing from pre to post training and maintained at follow-up, but no differences between training conditions.2

The current study used ratings of 189 therapists pulled from 826 MI sessions (of a potential total 1134 sessions). Some therapists did not attend all SP sessions and/or more commonly did not return all real patient recordings, resulting in 308 sessions that were not available for coding. To assess reliability some sessions were double or triple coded. To obtain greater precision we included session ratings from multiple raters in all analyses. However, we collapsed ratings within coder when sessions were double or triple coded by the same rater. This resulted in 929 ratings of the 826 sessions (164 sessions rated twice - 20%, 1 session rated 3 times). We included dummy codes for each coder in all models to account for any systematic differences among coders. Results of models that included coders did not differ substantially from simpler models that did not include coder.

Therapists

In total, 189 therapists with at least 1 session rating participated in the study between January 2005 and March 2007 (M = 4.4 rated sessions per therapist). Therapists were 68% female, and 72% Caucasian, 10% African American, 7% Native American, 6% Hispanic/Latino, 3% Asian, and 2% Pacific Islander. Mean age was 46.4 years (SD = 11.5), and mean length of experience in clinical service provision was 9.5 years (SD = 8.7). Twenty five percent had a Master’s degree, 4% a doctoral degree, 27% a Bachelor’s degree, 29% an Associate’s degree, and 14% a high school diploma or equivalent. A majority of the sample (61%) reported prior exposure to MI through varied means (11%; previous training workshop, 50%: reading of MI texts or journal articles) prior to study trainings.

Standardized and Real Patients

Of the total therapist sample, 187 therapists saw one of three SPs during at least one evaluation time point (485 sessions total; 2 of the 189 therapists failed to attend an SP session and did not have an SP observation). The SP protocol consisted of a single SP portraying a recently referred client with a substance use problem and background characteristics common for agency clientele. SPs were trained to provide realistic clinical vignettes (e.g., a mother struggling with methamphetamine who has lost her children to child protective services), but there was no specific script. The SP’s were trained to respond flexibly to counselors during sessions such that they responded in an MI theory consistent way to specific behaviors (e.g., defensiveness in response to confrontation; change talk in response to reflections). The process of assignment of SPs to therapists varied across sites and the open enrollment trial.3 Most therapists saw at least two different SPs, but SPs were not fully crossed (some therapists saw only 1 SP and each therapist did not treat all three SPs). However, each SP generally encountered a large segment of the therapist sample (nSP1 = 70 therapists, nSP2 = 78 therapists, and nSP3 = 124 therapists). On average, each therapist saw 1.5 SPs and had 2.59 SP sessions. One hundred and two (55%) therapists saw two SPs, and 85 therapists (45%) saw only 1 SP (no therapists saw all three SPs).

A total of 154 therapists returned a recording with a real patient they selected from their caseload for at least one time point (pre, post, and/or follow-up). The average number of real patient sessions per therapist was 2.21 (341 sessions total). No demographic or clinically descriptive data were available for real patients.

Measures

Motivational Interviewing Treatment Integrity 2.0 (MITI 2.0; Moyers et al., 2005)

All of each 20 minute session was rated using global indices and behavior tallies from the MITI, a commonly used measure of MI adherence. The MITI offers conceptually derived summary indices for measuring elements of MI adherence. The MITI is highly correlated with scales such as the Motivational Interviewing Skills Code (MISC) and is sensitive to the detection of improvements in MI skill after training (Moyers, Martin, Manuel, Hendrickson, & Miller, 2005).

The current study focused on commonly used summary scores for therapist adherence in MI. These included two session level “global” ratings (e.g. empathy, MI spirit), each scored on a 7-point Likert scale intended to capture gestalt impressions. An advantage of the current dataset over those obtained from clinical trials is the wide range of adherence scores (e.g., therapists were not trained to a certain level of adherence before participation). For example, scores on empathy spanned the entire range of the scale (from 1 to 7). A score of ‘1’for Empathy indicated a therapist had “no apparent interest in the client’s world view” and a ‘7’ indicated that the therapist “shows evidence of deep understanding of client’s point of view, not just for what has been explicitly stated but what the client means but has not yet said” (Moyers et al., 2005, p.14).

We used three additional summary scores derived from MI-relevant behavioral tallies throughout the session, (a) Percent open questions – the number of open questions divided by the total number of questions (open and closed), (b) Percent complex reflections - the number of complex reflections divided by the total number of reflections (simple and complex), and (c) Reflection to question ratio, which included the total number of reflections (complex and simple) divided by the total number of questions (open and closed) asked by the therapist. Raters received training and supervision in use of the MITI, and were blind to assessment timing and practitioner identifiers throughout their scoring process. Across codes, raters demonstrated adequate inter-rater reliability (ICC’s ranged from .43 to .94, M = .67, SD = .16), and intra-rater reliability (ICC’s ranged from .53 to .96, M = .79, SD = .13; Baer et al. 2009).

Data Analysis

Primary hypotheses were tested using Bayesian mixed effects models fit via the MCMCglmm package in R (Hadfield, 2010; R Core Development Team, 2011). The Markov chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) procedures used in fitting Bayesian models lead to a set of simulated parameters for each model, called the posterior distribution. Posterior distributions can be used to obtain point estimates and highest posterior density intervals (HPD; the Bayesian analogue of a confidence interval). Bayesian methods assume prior distributions for parameters. In typical applied Bayesian analysis, non-informative or ‘diffuse’ prior distributions are used, which weakly constrain parameter values, but typically do not influence substantive results. Normal distributions were used as priors for fixed effects and inverse Wishart priors were used for variance components. We used three MCMC chains, each with 100,000 iterations, including a burn-in of 5000 iterations. Each chain was thinned by taking every 100th draw. We assessed convergence with autocorrelation and trace plots, as well as the Gelman-Rubin statistic that compares between to within-chain variance. We used the mode and the 95% HPD interval of the simulated posterior distribution to summarize the posterior distribution for all parameters (Gelman & Hill, 2007). One of the attractive properties of Bayesian analysis is that the values of the posterior distribution can be combined to create posterior distributions of linear and non-linear combinations of parameters, making it straightforward to estimate CIs around ICCs and GCs. The mixed effects model is written as:

where Yij is the adherence score for patient i seeing therapist j. Because there were multiple coders, we included dummy variables (CODER1 and CODER2) to control for possible mean differences between the coders. The random effects, uSPj and uRPj capture differences among therapists in their average adherence scores for standardized and real patients, respectively, and eij is a patient-level residual term. 4 The random effects are distributed multivariate normal:

where and are the variance in adherence ratings across therapists for standardized and real patients and σuSPuRP is the covariance between therapist adherence with standardized and real patients. The covariance is then converted to a correlation. The patient-level residual is independent of the random effects and is normally distributed:

Estimation of therapist adherence with ICCs (Hypothesis 1)

To examine the size of between therapist differences in adherence ratings relative to total variation in adherence ratings (i.e., the therapist component of adherence ratings), we calculated the intra-class correlation (ICC) for therapists both for RPs and SPs. The ICC can be interpreted as the proportion of variance explained by therapists. It was computed as the ratio of the variance of the therapist random effects to the total variance (the sum of the residual variance and the variance of the therapist random effects).

Differences in therapist adherence (ICC’s) between standardized and real patients (Hypothesis 2)

We examined differences in ICCs between real and standardized patient sessions by subtracting the posterior distribution of the ICC for real patients and the ICC for the standardized patient sessions. We then calculated a 95% HPD interval of the difference.

Correlation of therapist adherence ratings from real and standardized patients (Hypothesis 3)

We examined the correlation of real and standardized patient ratings via the correlation of the random effects for therapists obtained from real and standardized patients.

Differences in Generalizability Coefficients (Hypothesis 4)

Finally, we examined the relative size of the generalizability coefficients from real and standardized patients across adherence measures. Similar to Hypothesis 2, we examined differences in GC’s by subtracting the posterior distribution of the GC for real patients and the GC for the standardized patient sessions, then calculating a 95% HPD interval of the difference. As an illustration, we also calculated the number of observations necessary to reach an adequate generalizability coefficient for assessments obtained from real and standardized patients (≥ .80). 5

Results

Global scales (empathy and MI spirit), percent open questions, and percent complex reflections were approximately normally distributed: (a) Empathy, M = 4.24, SD = 1.32, Range [1-7]; (b) MI Spirit, M = 3.85, SD = 1.24, Range [1-7]; (c) Percent Open Questions, M = 39.84, SD = 17.91, Range [0-100]; (d) % Complex Reflections, M = 42.77, SD = 23.13, Range [0-100]. The Reflection to Question ratio score was positively skewed, M = 0.82, SD = 0.95, Range [0-11], skew = 4.59, and was +1 log transformed.

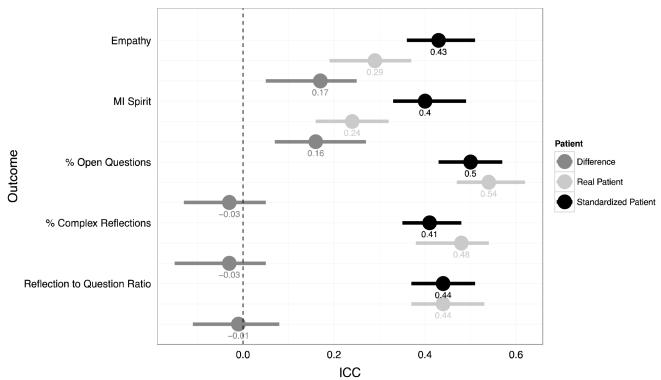

Figure 1 plots therapist ICCs and 95% HPD intervals. For each outcome, three ICCs are reported: a) real patients, b) standardized patients, and c) the difference between real and standardized patients. Consistent with Hypothesis 1, none of the HPD intervals for ICC’s included zero, suggesting significant variability in therapist adherence scores. The average ICC with standardized patients across adherence measures was .44, Range [.41-.50], indicating that therapists accounted for approximately 40% of the variance across adherence measures when patient presentation was held constant. The largest ICCs were for Empathy (.44) and Percent Open Questions (.50). Similarly, the average ICC for real patients across adherence measures was .40, Range [.24-.54]. The largest ICCs were Percent Open Questions (.54), and Percent Complex Reflections (.48).

Figure 1.

Intra-class correlations (ICCs) and HPD intervals for therapists on each outcome derived from SP (black), RP sessions, (light gray), and the difference between SP and RP ICC estimates (dark grey).

Hypothesis 2 was partially supported

In examining the difference between real and standardized patient ICCs, therapist ICCs for Empathy and MI Spirit from standardized patients were larger than those from real patients (i.e., the HPD interval of the difference score did not include zero) - 17 and 16-point differences in percents for each outcome respectively. Alternatively, the ICCs for adherence measures based on behavioral counts were not significantly different between real and standardized patients (the HPD interval of the difference included zero).

Figure 2 provides estimates of the correlation of therapist adherence with real and standardized patients. The average correlation was .40, Range [.04-.75]. Partially consistent with Hypothesis 3, three of the correlations between therapist adherence from SPs and RPs were moderate to large in size and HPD intervals did not include zero. However, correlations were small and HPD intervals included zero for % open questions and % complex reflections.

Figure 2.

Correlations (r) for therapist adherence estimates obtained from SPs and RPs. Correlations are derived from Bayesian mixed effects models and the error bars represent 95% HPD intervals.

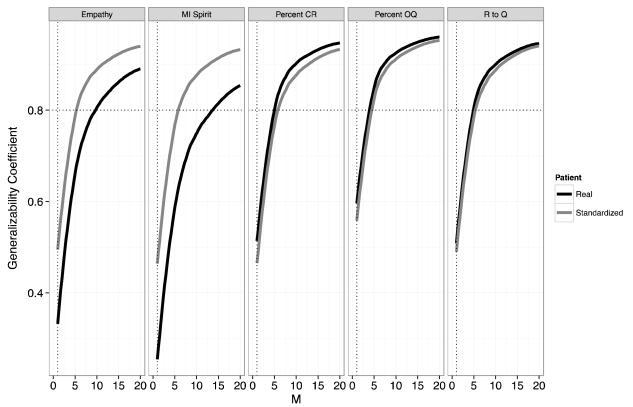

We also examined the relative size of the generalizability coefficients (GCs) from real and standardized patients across adherence measures based on the average number of standardized (M = 2.59) and real patient (M = 2.21) observations per therapist. Figure 3 provides GCs and HPD intervals for each outcome as well as the difference between real and standardized patients. The average GC from standardized patients across adherence measures was .67, Range [.63-.73]. The average GC from real patients across adherence measures was .58, Range [.41-.72]. Consistent with differences for therapist ICCs between real and standardized patient sessions, GCs for Empathy and MI Spirit from standardized patients were larger than those from real patients (i.e., the HPD interval of the difference score did not include zero). This suggests that for these measures there is more therapist true score variance in SP observations. However, the GCs for adherence measures based on behavioral counts were not different between real and standardized patients (the HPD interval included zero).

Figure 3.

Generalizability coefficients based on the average number of SP and RPs seen by therapists. SP (m=2.59) and RP (m=2.21)

As an illustration, figure 4 depicts the number of observations (i.e., patients) required to obtain a reliable estimate (GC of .80) of therapist adherence on a specific outcome. The overall number of observations required across standardized and real patients was 6.6. Across measures, two fewer standardized patient observations were required to obtain a reliable estimate of therapist adherence (average number of standardized patients observations necessary to achieve .80 = 5.6; real patient = 7.6), but this difference was restricted to global ratings such as Empathy and MI Spirit. Six standardized patients ratings would be necessary to obtain a GC of .80 for Empathy and MI Spirit, while 14 real patient observations would be necessary to obtain a similar estimate of MI Spirit and 10 for Empathy.

Figure 4.

Generalizability Coefficients (GCs) for each outcome as a function of the number observations per therapist (M). The horizontal dashed line indicates where the number of patients results in a GC of .80. The vertical dashed line indicates the GC with one session.

Discussion

Findings from our study suggest that an established measure such as the MITI—when used in a large MI dissemination trial—does capture variability in therapist adherence to MI. For both real and standardized patients, differences in therapist adherence were relatively large - larger than most estimates obtained from large clinical trials (e.g., Imel et al., 2010; Dennhag et al. 2012; Boswell et al. 2013). Further, the number of patients required to obtain a stable estimate of therapist adherence was considerably smaller than other published estimates of therapist level generalizability scores (see Crits-Christoph et al., 2011; Dennhag et al., 2012). This is likely the result of larger therapist adherence ICC’s in this dissemination trial (see Baldwin et al., 2013). It appears that the use of adherence data from a large dissemination trial can be a valid method for capturing differences in whether a therapist can perform a specific treatment such as MI.

The correlation of therapist adherence ratings with real and standardized patients was inconsistent across measures. However, ratings of therapist adherence such as empathy, MI spirit, and reflection to question ratio obtained from SP sessions offer some predictive validity in terms of a therapist’s performance with real patients. These correlations are much larger than those obtained from the recent Decker et al. (2013) study. The reason for this difference is not clear, but may be a result of fewer sessions per therapist in the Decker et al. study (approximately 1.6 total observations per therapist for real and standardized patients respectively), potentially leading to unreliable estimates of therapist adherence. As indicated by figure 4, when the number of sessions is small even adding 1 additional observation has a dramatic impact on the reliability of therapist adherence scores, and may lead to an increase in the correlation of therapist adherences scores.

ICCs and GCs for therapists obtained from SP sessions were larger than RP sessions for the global adherence ratings (empathy and MI spirit). However, it is notable that SP-RP correlations for summary scores such as Percent Open Questions and Percent Complex Reflections were small and HPD intervals included zero. It is possible different selection processes were responsible for therapist differences in these scores with SPs and RPs (therapists selected their own RP sessions for evaluation). Therapists with low ratings on these specific measures in SP sessions may have been able to select specific RP sessions in which their performance was more obviously consistent with MI, decreasing the correspondence with SP sessions (SP sessions were not selected by therapists). In addition, estimates of inter-rater reliability for complex reflections are often low (Moyers et al., 2005), which could attenuate the relationship between therapist performance with SPs and RPs. It may be that the session level scores are tapping into a more stable therapist level trait, while utterance level behavioral counts are more dependent on the given client (i.e., how responsive the client is to open questions and reflections may reinforce therapist tendency to use them). However, based on the current study, using SP’s to predict a therapists future performance on Percent Open Questions and Percent Complex Reflections remains questionable and in need of further study.

Limitations

As noted above, the current study relies on analyses of an existing dataset collected during a large MI dissemination trial (Baer et al., 2009). Accordingly, several features of this dataset limit the present findings. First, only three SPs were used in the study, and all were trained to present a case with similar complexity and difficulty. This design feature makes sense when evaluating training but may limit the generalizability of therapist differences in adherence measures to the SP profiles evaluated in this study. In addition, standardized patients could have changed their behavior overtime as a result of practice, potentially influencing ratings of therapists evaluated later. Second, RPs were selected by the therapist. Although there was no punishment for poor performance (supervisors were not privy to ratings), some therapists may have selected only those patients with whom they felt they performed well, which may have increased ICCs and decreased correlations with therapist RP performance. The range of adherence scores with RPs reflects therapists’ ability to perform certain skills when they know they are being evaluated (and thus likely represents an upwardly biased estimate of adherence). Despite this limitation there was a full range of therapist adherence scores, suggesting that at least some therapists who lacked certain skills were not able or did not try to hide this.

Another limitation of the training data used in this study is that we could not connect adherence data with clinical outcomes - a trade off resulting from a study that focuses on therapists as the primary aim. This limitation is important as a recent meta-analysis indicates that the relationship between scores on adherence measures and treatment outcomes is small and non-significant (Webb et al. 2010). In addition, therapists who have received adequate training in an evidenced based treatment do not necessarily produce uniform outcomes (Laska et al. 2013). In the future, the use of more advanced medical records technology might connect regularly recorded patient outcomes with data on therapist adherence such that large scale evaluations may be possible. Thus, while adherence measures tell us about therapists, the importance of these behaviors in terms of clinical outcomes remains to be determined.

Clinical Implications

The findings reported above rely on what may appear to be subtle methodological distinctions, but there are numerous clinical implications. While observer ratings of therapists are not typically available in community settings, as efforts to disseminate evidence based practices increase, direct evaluation of therapist behavior is likely to rise. This information may have a direct impact on the careers, reputations, and financial livelihood of practitioners (consider the evaluation of teacher effectiveness in the New York (http://www.nytimes.com/schoolbook/) and California; (http://projects.latimes.com/value-added/ wherein teacher specific estimates of student performance on standardized tests were published in an searchable online database). Accordingly, valid but clinically feasible methods for evaluating therapists are critical.

Research suggesting that the use of standardized patients can provide valid information about therapist adherence is an important step in the process. With respect to clinical trials, it appears that the practice of using standardized patients to evaluate therapists prior to work with real patients could provide useful information about how a therapist will perform with real patients on certain outcomes. Yet, the generalizability coefficients reported in this paper suggest that one observation of a therapist’s performance does not result in a reliable estimate. If based on a single evaluation, judgments made about therapist adherence before and during clinical trials will likely be biased and unstable – potentially leading to the inappropriate exclusion of providers and the inclusion of therapists who are not as adherent as they appear to be. For example, the Motivational Interviewing Network of Trainers (MINT) practice of requiring one tape coded for adherence (http://www.motivationalinterviewing.org/pathways-membership) is not likely to provide a reliable estimate of therapist’s tendency to use MI behaviors in session.

The use of standardized patients would appear particularly useful for trainers, managers, and researchers with brief interventions such as MI that last a few sessions or for evaluation related to specific clinical scenarios (e.g., evaluate therapist response to suicidal ideation (SI) without waiting on a patient to present with actual SI, randomly assign providers to specific patient profiles – high vs. low interpersonal aggression; Boswell et al., 2013; see Francis et al. 2005 for an example of randomizing therapists to different SP profiles), or when attempting to obtain a gestalt impression of a therapist beyond simple behavioral counts (e.g., empathy ratings). Additional logistic advantages include having control over scheduling interviews and having the SP be responsible for returning the session recording – resulting in less missing data (Baer et al., 2004). Finally, several risks to patients are decreased. There is no need to expose patients to therapists of unknown skill and concerns about patient confidentiality stemming from the transportation and storage of audio from treatment sessions are eliminated. However, the use of standardized patients to evaluate therapists who provide more long-term treatments (e.g., 20 sessions of CBT) is in need of further study.

SPs can provide reasonably valid assessments of therapist adherence, and thus represent an additional strategy for evaluating therapists that involves less risk to patients, is user friendly, and potentially more efficient than real patients on some measures. More difficult, will be to determine how to employ the use of standardized patients in a way that facilitates the clinical decisions made by supervisors, administrators, and patients. Specifically, should therapists be withheld from practicing if they are unable to demonstrate specific skills after an adequate sample of work with standardized patients? While this strategy might protect patients, the loss of evaluating providers with actual patients would detract from both training and the evaluation of treatments in real world settings. As a result, the procedure for training and evaluating provider behavior should likely involve a combination of targeted work with standardized patients and the observation of work with low-risk real patients.

Acknowledgments

Funding for the preparation of this manuscript was provided by National Institute of Drug Abuse (NIDA) of the National Institutes of Health under award number R34/DA034860 and the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA) under award number R01/AA018673. The University of Washington Alcohol Drug Abuse Institute (ADAI) also provided support for the preparation of the manuscript (Grant #: U10 DA013714). The NIDA Clinical Trials network provided support for the initial conduct of the research. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health or ADAI.

Footnotes

We calculated the average of therapists in clinical trials and studies based on data reported in a recent meta-analysis of therapist differences in treatment outcomes (Baldwin & Imel, 2013; see Table 8.2).

Ratings in real and standardized patient sessions were not used by supervisors for evaluating therapists in any way. (see Baer et al., 2009 for additional detail).

At the six primary study sites (Baer et al, 2009) an effort was made to balance therapists seeing same or different SPs at baseline and post-training only. No such effort was made at pilot sites and the open-enrollment cohort, nor was choice of SP controlled at the follow-up assessment for any site. Furthermore, different SPs worked at different sites.

Although we estimated random effects separately for SPs and RPs, we estimated a common residual error term (the same error term was used to calculate ICC’s for real and standardized patients). As a sensitivity analysis, we also fit models with stratified residual error terms - one for SPs and one for RPs. Results were consistent with the simpler model. Perhaps as a result of over parameterization, several models did not converge adequately. Consequently, we used models with a common error term for primary analyses.

An important caveat is that the design of the dissemination trial used in the current study has limitations that are the inverse of a typical clinical trial. We do not have information on the identity of the real patients in the trial and thus do not know if the therapist provided sessions for the same client or different clients. Accordingly, it was not possible to account for variability due to real patients. In addition, although there were many therapists, there were only three standardized patients. Given this sample size, it was not feasible to examine standardized patient variability via a random effect. To provide some test of standardized patient effects on adherence scores, we conducted a separate set of analyses on the data obtained from standardized patients. We entered standardized patient as a fixed effect predictor (dummy codes) of therapist adherence. On the five outcomes, there was only one significant standardized patient effect. There was a small decrease in reflection to question ratio for one standardized patient. The ICCs obtained from these models were consistent with the results from the full model for standardized patient.

References

- Apodaca TR, Magill M, Longabaugh R, Jackson KM, Monti PM. Effect of a significant other on client change talk in motivational interviewing. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2013;81:35–46. doi: 10.1037/a0030881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baer JS, Rosengren DB, Dunn CW, Wells EA, Ogle RL, Hartzler B. An evaluation of workshop training in motivational interviewing for addiction and mental health clinicians. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2004;7:99–106. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2003.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baer JS, Wells EA, Rosengren DB, Hartzler B, Beadnell B, Dunn C. Agency context and tailored training in technology transfer: A pilot evaluation of motivational interviewing training for community counselors. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2009;37:191–202. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2009.01.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baldwin SA, Imel ZE, Atkins D. The influence of therapist variance on the dependability of therapists’ alliance scores: a brief comment on “The dependability of alliance assessments: the alliance-outcome correlation is larger than you think”. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2012;80:947–51. doi: 10.1037/a0027935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boswell JF, Gallagher MW, Sauer-Zavala SE, Bullis J, Gorman JM, Shear MK, Woods S, Barlow DH. Patient characteristics and variability in adherence and competence in cognitive-behavioral therapy for panic disorder. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2013;81:443–54. doi: 10.1037/a0031437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cardinet J, Johnson J, Pini G. Quantitative methods series. Routledge/Taylor & Francis; New York: 2010. Applying generalizability theory using EduG. [Google Scholar]

- Crits-Christoph P, Gibbons MBC, Hamilton J, Ring-Kurtz S, Gallop R. The dependability of alliance assessments: The alliance–outcome correlation is larger than you might think. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2011;79:267. doi: 10.1037/a0023668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Decker SE, Carroll KM, Nich C, Canning-Ball M, Martino S. Correspondence of Motivational Interviewing Adherence and Competence Ratings in Real and Role-Played Client Sessions. Psychological Assessment. 2013;25:306–312. doi: 10.1037/a0030815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dennhag I, Gibbons MBC, Barber JP, Gallop R, Crits-Christoph P. How many treatment sessions and patients are needed to create a stable score of adherence and competence in the treatment of cocaine dependence? Psychotherapy Research. 2012;22:475–488. doi: 10.1080/10503307.2012.674790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Francis N, Rollnick S, McCambridge J, Butler C, Lane C, Hood K. When smokers are resistant to change: experimental analysis of the effect of patient resistance on practitioner behaviour. Addiction. 2005;100:1175–1182. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2005.01124.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gelman A, Hill J. Data Analysis Using Regression And Multilevel/Hierarchical Models. Cambridge University Press; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Hadfield JD. MCMC methods for multi–response generalised linear mixed models: The MCMCglmm R package. Journal of Statistical Software. 2010;33:1–22. [Google Scholar]

- Imel ZE, Baer JS, Martino S, Ball SA, Carroll KM. Mutual influence in therapist competence and adherence to motivational enhancement therapy. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2011;115:229–36. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2010.11.010. doi:10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2010.11.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kenny DA, Kashy DA, Cook WL, Simpson JA. Dyadic Data Analysis. Guilford; New York: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Laska KM, Smith TL, Wislocki AP, Minami T, Wampold BE. Uniformity of evidence-based treatments in practice? Therapist effects in the delivery of cognitive processing therapy for PTSD. Journal of counseling psychology. 2013;60:31–41. doi: 10.1037/a0031294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marcus DK, Kashy DA, Baldwin SA. Studying psychotherapy using the one-with-many design: The therapeutic alliance as an exemplar. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 2009;56:537–548. doi:10.1037/a0017291. [Google Scholar]

- Miller WR, Yahne CE, Moyers TB, Martinez J, Pirritano M. A randomized trial of methods to help clinicians learn motivational interviewing. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2004;72(6):1050–1062. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.72.6.1050. doi:10.1037/0022-006X.72.6.1050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller WR, Mount K. A small study of training in motivational interviewing: Does one workshop change clinician and client behavior? Behavioural and Cognitive Psychotherapy. 2001;29:457–471. [Google Scholar]

- Miller WR, Rollnick S. Motivational interviewing. 3rd ed Guilford; New York: 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Moyers TB, Martin T, Manuel JK, Hendrickson SML, Miller WR. Assessing competence in the use of motivational interviewing. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2005;28:19–26. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2004.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moyers T, Martin T, Manuel J. Motivational interviewing treatment integrity (MITI) coding system. The University of New Mexico Center on Alcoholism; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Stimmel B, Cohen D, Fallar R, Smith L. The use of standardized patients to assess clinical competence: does practice make perfect? Medical Education. 2006;40(5):444–449. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2929.2006.02446.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- R Core Team . R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing; Vienna, Austria: 2012. ISBN 3-900051-07-0. [Google Scholar]

- Wampold BE, Brown GS. Estimating Variability in Outcomes Attributable to Therapists: A Naturalistic Study of Outcomes in Managed Care. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2005;73:914–923. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.73.5.914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Webb N, Shavelson R, Haertel EH. Reliability coefficients and generalizability theory. Handbook of Statistics. 2006;26:1–44. [Google Scholar]

- Webb CA, DeRubeis RJ, Barber JP. Therapist adherence/competence and treatment outcome: A meta-analytic review. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2010;78:200–211. doi: 10.1037/a0018912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]