Abstract

Background

Epidemiological studies have reported the preventive effect of vitamin A intake on bladder cancer. However, the findings are inconsistent. To address this issue we conducted a meta-analysis to investigate the quantitative effects of vitamin A on bladder cancer.

Methods

We searched MEDLINE and Embase databases and the references of the relevant articles in English to include studies on dietary or blood vitamin A for the risk of bladder cancer. We performed a meta-analysis using both fixed-effects and random-effects models.

Results

Twenty-five articles on dietary vitamin A or blood vitamin A were included according to the eligibility criteria. The pooled risk estimates of bladder cancer were 0.82 (95% CI 0.65, 0.95) for total vitamin A intake, 0.88 (95% CI 0.73, 1.02) for retinol intake, and 0.64 (95% CI 0.38, 0.90) for blood retinol levels. We also found inverse associations between subtypes of carotenoids and bladder cancer risk.

Conclusion

The findings of this meta-analysis indicate that high vitamin A intake was associated with a lower risk of bladder cancer. Larger studies with prospective design and rigorous methodology should be considered to validate the current findings.

Keywords: Bladder cancer, Meta-analysis, Retinol, Vitamin A

Background

Bladder cancer is the fifth most common cancer among with an estimated 386,000 new cases and 150,000 deaths world-wide in 2008 [1]. It has the highest lifetime treatment cost for any cancer [2]. Carcinogens or dietary chemopreventive agents can be concentrated in urine and have prolonged exposure to the bladder epithelium, making it an ideal target for preventative strategies [3].

Environmental factors, particularly dietary factors, have been postulated to play important roles in the etiology of bladder cancer [4]. Vitamin A and retinol are hypothesized to reduce the risk of bladder cancer due to their roles in the regulation of cell differentiation and apoptosis [5]. A previous meta-analysis, including seven case–control studies and three cohort studies, found no association of bladder cancer in relation with diets low in retinol and β-carotene [6]. Since the meta-analysis was published, epidemiologic studies of vitamin A, retinol (preformed vitamin A), and carotenoids in relation to the risk of bladder cancer have documented inconsistent results. In the present study, we analyzed this relationship further by conducting an updated meta-analysis of relevant studies. This updated analysis will allow us to provide more precise risk estimates than the previous analysis according to different carotenoids. We also examined the association between blood vitamin A concentrations and bladder cancer risk.

Methods

Search strategy

We searched MEDLINE and Embase databases to September 2013 for studies in humans on the relationship between vitamin A and incidence of bladder cancer. The search query was the following: (retinol or “vitamin A” or beta-carotene or carotenoids) and (“bladder cancer” or “urothelial cancer” or “urinary tract cancer” or “urinary bladder neoplasms” [MeSH Terms]). We also reviewed the reference lists from reviews, meta-analyses and other relevant publications to search for further studies to be included.

Selection criteria

Studies were included in this meta-analysis if they met the following criteria: they presented original data from case–control or cohort studies; the exposure of interest was intake of vitamin A (retinol, carotene, or other carotenoids) or blood (plasma or serum) levels of vitamin A; the outcome of interest was bladder cancer or urothelial cancer; and odds ratio or relative risk estimates with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) (or data to calculate these) were reported and adjusted for at least age, sex, and smoking. If the same study was used in more than one publication, we included the one with the largest number of cases. Because the overwhelming majority of tumors occurred in the bladder, and the renal pelvis and ureter are covered by the same urothelium, the term bladder cancer was used as a synonym for all neoplasms of the bladder, renal pelvis, and ureter.

Data extraction

Data extracted from each study were the following: the first author, publication year, country where the study was carried out, study period, participant sex and age, sample size, anatomical site of the neoplasm, research contents, study quality, and adjusted covariates. We used the odds ratio or relative risk with 95% CI of the highest intake (or blood level) group for bladder cancer compared with the lowest intake (or blood level) group reported in each study. Data extraction was conducted independently by two authors (JT and RW), with disagreements resolved by consensus.

Quality assessment

We assessed the quality of all included studies using the Newcastle-Ottawa scale. (http://www.ohri.ca/programs/clinical_epidemiology/oxford.asp). This is an eight-item instrument that allows for the assessment of the patient population and selection, study comparability, follow-up, and the outcome of interest. Interpretation of the scale is performed by awarding points, or ‘stars’, for high-quality elements. The stars are then added up and used to compare study quality in a quantitative manner. The maximum score is nine points, representing the highest methodological quality.

Statistical analysis

Depending on heterogeneity between studies, we used fixed- or random-effects models to calculate summary risk estimates (REs) and 95% CIs for the highest versus the lowest levels of vitamin A. Statistical heterogeneity among studies was evaluated using the Q [7] and I 2 [8] statistic. In the sensitivity analysis, one study at a time was removed and the rest analyzed to evaluate whether the results could have been affected significantly by a single study. We also conducted subgroup analyses by study design, sex, geographic area, and source of vitamin A intake (diet or supplement). If results were reported for both dietary and total vitamin A (foods and supplements combined), we used the results for total vitamin A in the main analysis. Publication bias was evaluated with the use of the Egger’s test [9]. All statistical analyses were carried out with Stata 11 (StataCorp, College Station, TX, USA). A two-tailed P-value of less than 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

Results

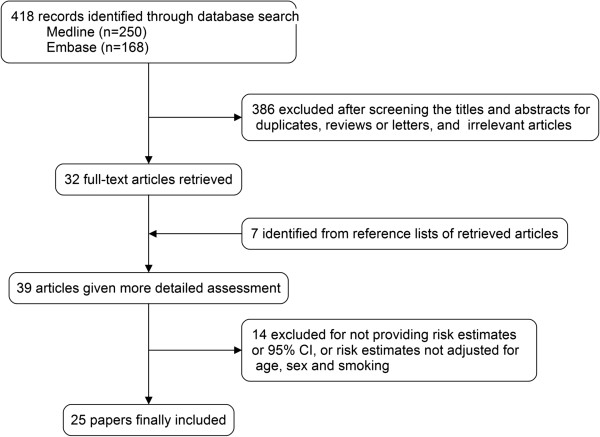

A flowchart of the identification of relevant studies is shown in Figure 1. We identified a total of 418 articles (168 from Embase and 250 from MEDLINE) in our initial search. Of these, 386 were excluded after screening the titles and abstracts because of duplicates, reviews, and non-relatedness. Seven articles were identified from the references of relevant studies. The remaining 39 articles were given a more detailed assessment, and 14 studies were excluded because they did not meet the inclusion criteria. Finally, 25 papers were included in the present meta-analysis [10-34].

Figure 1.

Flowchart of study selection.

Table 1 shows the main characteristics of all 25 studies included in the final analysis. The 25 studies were published between 1988 and 2013 and involved a total of 11,580 cases. Eleven were cohort studies [14,16,18-20,23,25,29,31,32],[34] and 14 were case–control studies [10-13,15,17,21,22,24,26-28,30],[33]. Fifteen studies were conducted in North America [10,12,14-16,20-24,28,30,31,33],[34], eight in Europe [11,13,18,19,26,27,29,32], and two in Japan [17,25]. All 25 studies provided REs adjusted for at least age, sex, and smoking. Five reports provided results for blood vitamin A levels [20,24,25,28,32]; three measured plasma vitamin A levels [24,28,32] and two measured serum vitamin A levels [20,25]. Some studies included neoplasms of the urinary tract as cases [11,12,18,20,25,29,32], most of which were found to involve bladder cancer, whereas others selected only bladder cancer. The quality score of studies ranged from six stars to nine stars according to the nine-star Newcastle-Ottawa Scale except for one study by Hung et al. (five stars) [24].

Table 1.

Study characteristics of published cohort and case–control studies on vitamin A and bladder cancer risk

| Authors and publication year | Study design | Country | Study period | Sex | Age (years) | Cases/subjects | Anatomical site | Parameters examined | Study quality a | Variables of adjustment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [10] |

PCC |

Canada |

1977 to 1982 |

M/F |

35 to 79 |

826/1,618 |

Bladder |

Diet: vitamin A, retinol, β-carotene |

7 |

Age, sex, area of residence, smoking, history of diabetes |

| [11] |

PCC |

Sweden |

1985 to 1987 |

M/F |

40 to 74 |

418/929 |

Urothelium |

Supplement: vitamin A, β-carotene |

7 |

Age, sex, smoking |

| Diet: retinol | ||||||||||

| [12] |

PCC |

USA |

1977 to 1986 |

M/F |

30 to 93 |

261/783 |

Urothelium |

Total: vitamin A, retinol, carotenoids |

8 |

Age, sex, ethics, smoking |

| [13] |

PCC |

Spain |

1985 to 1986 |

M |

< 80 |

432/1,224 |

Bladder |

Diet: retinol, carotene |

8 |

Age, sex, smoking, total calories |

| [14] |

Cohort |

USA |

1981 to 1989 |

M |

65 to 84 |

71/70,159 |

Bladder |

Supplement: vitamin A |

5 |

Age and smoking |

| Diet: β-carotene | ||||||||||

| [15] |

PCC |

USA |

1981 to 1984 |

M/F |

45 to 65 |

262/667 |

Bladder |

Diet: vitamin A, retinol, β-carotene |

8 |

Age, sex, county, smoking, calories |

| Supplement: vitamin A, retinol | ||||||||||

| Total: vitamin A | ||||||||||

| Michand et al. 2000 |

Cohort |

USA |

1986 to 1998 |

M |

40 to 75 |

320/51,529 |

Bladder |

Total: vitamin A |

7 |

Age, energy, pack-years of smoking, current smoking status, geographic region of the USA, cruciferous vegetable intake, total fluid intake |

| [17] |

HCC |

Japan |

1996 to 1999 |

M/F |

20 to 99 |

297/692 |

Bladder |

Diet: vitamin A, retinol, carotene |

6 |

Age, sex, smoking, occupational history as a cook |

| Total: vitamin A, retinol, carotene | ||||||||||

| [18] |

Cohort |

Netherlands |

1986 to 1992 |

M/F |

55 to 69 |

569/3,692 |

Urinary tract |

Total: retinol, α-carotene, β-carotene, β-cryptoxanthin, lycopene, lutein/zeaxanthin |

8 |

Age, sex, cigarette smoking amount, duration of smoking |

| Michand et al. 2002 |

Cohort |

Finland |

1985 to 1998 |

M |

50 to 69 |

344/27,111 |

Bladder |

Diet: vitamin A, α-carotene, β-carotene, β-cryptoxanthin, lycopene, lutein/zeaxanthin |

7 |

Age, duration of smoking, smoking dose, total energy, trial intervention |

| [20] |

Cohort (nested) |

USA |

1971 to 1995 |

M/F |

52 to 71 |

111/222 |

Urothelium |

Serum: retinol, carotenoids, α-carotene, β-carotene, β-cryptoxanthin, lycopene, lutein/zeaxanthin |

8 |

Age, sex, smoking |

| [21] |

PCC |

USA |

1987 to 1996 |

M/F |

25 to 64 |

1,592/3,184 |

Bladder |

Diet: retinol, carotenoids, α-carotene, β-carotene, β-cryptoxanthin, lycopene, lutein/zeaxanthin |

8 |

Age, sex, education, number of cigarettes smoked per day, number of years of smoking, smoking status, lifetime use of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, number of years employed as a hairdresser/barber |

| [22] |

HCC |

USA |

1999 to 2003 |

M/F |

Not mentioned |

409/860 |

Bladder |

Diet: carotenoids, provitamin A, non-provitamin A |

7 |

Age, gender, ethnicity, smoking status, pack-years of smoking, total energy |

| [23] |

Cohort |

USA |

1980 to 2000 |

F |

30 to 55 |

237/88,796 |

Bladder |

Total: vitamin A, α-carotene, β-carotene, β-cryptoxanthin, lycopene, lutein/zeaxanthin |

7 |

Age, pack-years of smoking, current smoking, total caloric intake |

| [25] |

Cohort (nested) |

Japan |

1990 to 2007 |

M/F |

>40 |

42/1,666 |

Urothelium |

Serum: provitamin A, retinol, carotenes, carotenoids, α-carotene, β-carotene, β-cryptoxanthin, lycopene, lutein/zeaxanthin |

7 |

Age, sex, smoking, alcohol consumption, body mass index, total cholesterol, education |

| [24] |

HCC |

USA |

1993 to 1997 |

M/F |

Not mentioned |

84/257 |

Bladder |

Plasma: α-carotene, β-carotene, β-cryptoxanthin, lycopene, lutein, zeaxanthin |

5 |

Age, sex, pack-years of smoking, education |

| [26] |

PCC |

Belgium |

1999 to 2004 |

M/F |

Not mentioned |

178/540 |

Bladder |

Diet: retinol |

7 |

Sex, age, smoking status, number of cigarettes smoked per day, number of years smoking, occupational exposure to PAH or aromatic amines, total fruit and vegetable consumption, intake of vitamin E and C and total anti-oxidant status |

| [27] |

HCC |

Spain |

1998 to 2001 |

M/F |

Not mentioned |

912/1,789 |

Bladder |

Diet: retinol and carotenoids |

6 |

Age, gender, region, smoking status, smoking duration |

| [28] |

HCC |

USA |

1999 to |

M/F |

Not mentioned |

386/773 |

Bladder |

Diet: retinol |

6 |

Age, gender, ethnicity, smoking status, number of cigarettes per day, smoking duration |

| Plasma: retinol | ||||||||||

| [29] |

Cohort |

Denmark |

1993 to 2006 |

M/F |

50 to 64 |

322/55,557 |

Urothelium |

Diet: β-carotene |

8 |

Age, intake of vitamin C, vitamin E, and beta-carotene, smoking status, smoking duration, smoking intensity, passive smoking, work exposure. |

| Supplement: β-carotene | ||||||||||

| Total: β-carotene | ||||||||||

| [30] |

PCC |

USA |

1997 to 2001 |

M/F |

25 to 74 |

322/561 |

Bladder |

Total: carotenoids, α-carotene, β-carotene, β-cryptoxanthin, lycopene, lutein |

8 |

Age, sex, smoking status, total energy intake |

| [31] |

Cohort |

USA |

2000 to 2007 |

M/F |

50 to 76 |

330/77,050 |

Bladder |

Supplement: β-carotene and retinol |

8 |

Age, sex, race, education, family history of bladder cancer, smoking status/recency of smoking, pack-years of smoking, servings per day of fruits, servings per day of vegetables |

| [33] |

PCC |

USA |

2001 to 2004 |

M/F |

30 to 79 |

1,418/2,589 |

Bladder |

Diet: vitamin A, α-carotene, β-carotene |

8 |

Age, gender, region, race, Hispanic status, smoking status, usual body mass index, total energy |

| [32] |

Cohort (nested) |

Europe |

1990 to 2005 |

M/F |

25 to 70 |

856/1,712 |

Urothelium |

Diet: β-carotene |

8 |

Age at blood collection, study center, sex, date of blood collection, time of blood collection, fasting status; further adjusted for smoking status, duration, and intensity |

| Plasma: carotenoids, α-carotene, β-carotene, β-cryptoxanthin, lycopene, lutein, zeaxanthin | ||||||||||

| [34] | Cohort | USA | 1993 to 2007 | M/F | 45 to 75 | 581/185,885 | Bladder | Diet: vitamin A, α-carotene, β-carotene, β-cryptoxanthin, lycopene, lutein | 8 | Age, ethnicity, total energy intake, family history, employment in a high-risk industry, smoking, number of years since quitting, interactions of ethnicity with status |

aEvaluated by the nine-star Newcastle-Ottawa Scale. HCC, hospital-based case–control study; PCC, population-based case–control study.

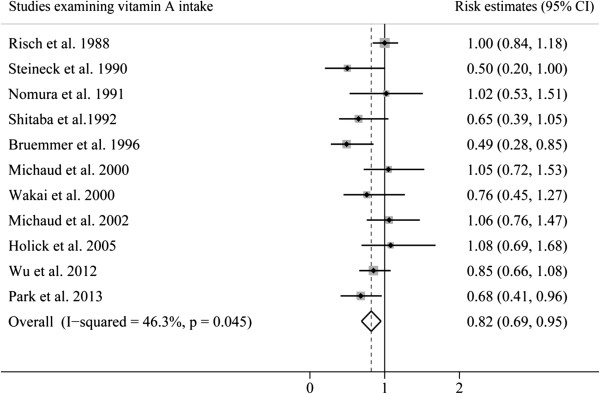

High versus low vitamin A intake or blood vitamin A levels

The analyses of vitamin A intake and bladder cancer risk were based on 11 studies. Figure 2 shows that results on vitamin A intake in relation to bladder cancer risk were inconsistent, with both inverse and positive associations reported. The pooled RE of bladder cancer for the highest versus lowest categories of vitamin A intake was 0.82 (95% CI 0.65, 0.95), suggesting that vitamin A intake was significantly associated with decreased risk of bladder cancer. There was moderate heterogeneity among studies (P = 0.045, I 2 = 46.3%). The Egger test showed no evidence of publication bias (P = 0.057).

Figure 2.

Pooled risk estimates of bladder cancer for the highest versus lowest categories of total vitamin A intake.

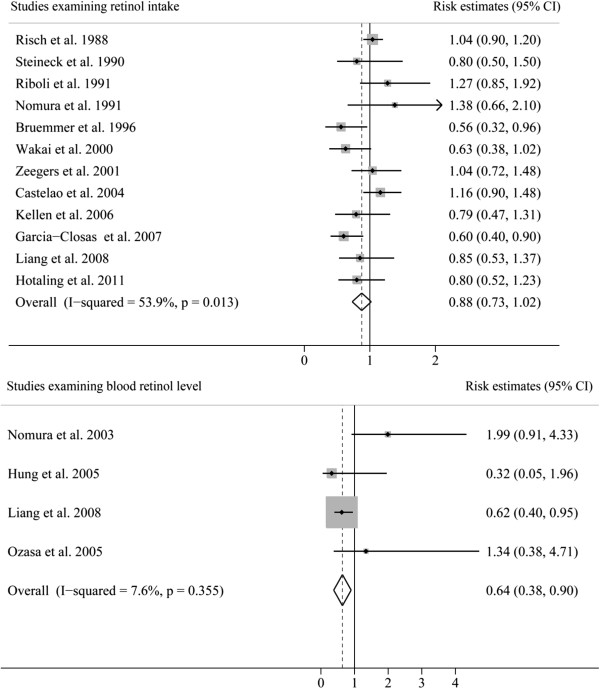

The REs for each study and all studies combined for the highest versus lowest categories of retinol intake or blood retinol level are shown in Figure 3. High intake of retinol was associated with a reduced but non-significant risk of bladder cancer (RE 0.88; 95% CI 0.73, 1.02), whereas high blood level of retinol was strongly associated with reduced risk of bladder cancer (RE 0.64; 95% CI 0.38, 0.90). There was significant heterogeneity among studies of retinol intake (P = 0.013; I 2 = 53.9%) but not among studies of blood retinol levels (P = 0.355; I 2 = 7.6%). The P-value for the Egger test of retinol intake was 0.10, suggesting a low probability of publication bias.

Figure 3.

Pooled risk estimates of bladder cancer for the highest versus lowest categories of retinol intake or blood retinol level.

To explore the heterogeneity among studies of vitamin A intake and bladder cancer, we performed sensitivity analyses. A sensitivity analysis omitting one study at a time and calculating the pooled REs for the remaining studies showed that the study by Bruemmer et al. [15] substantially influenced the heterogeneity for total vitamin A intake. After excluding this single study, there was no study heterogeneity (P = 0.198; I 2 = 26.7%), and the RE for the highest versus lowest category of vitamin A intake was essentially unchanged (RE 0.88; 95% CI 0.78, 0.97). However, we found no study significantly influenced the pooled RE for retinol intake.

We also performed subgroup analyses by study design, geographical region, gender, and source of intake (Table 2). For total vitamin A intake, when carrying out a stratified analysis for study design, the summary RE intake became non-significant for cohort studies. A significant inverse association was observed in North American studies, but not in European and Japanese studies. In a subgroup analysis by source of vitamin A intake, we observed a significantly decreased risk of bladder cancer in patients with supplementary intake, but not with dietary or dietary plus supplementary intake. For retinol intake, the stratified analysis did not show any statistically significant difference in summary estimates between strata. Unexpectedly, high intake of retinol in women seemed to increase the risk of bladder cancer significantly, although only two studies were included in this subgroup.

Table 2.

Pooled risk estimates for the associations between total vitamin A and retinol and bladder cancer stratified by study design, gender, geographical region, and source of intake

|

Subgroup |

Total vitamin A |

Retinol |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| RE (95% CI) | P heterogeneity ( I 2 score) | RE (95% CI) | P heterogeneity ( I 2 score) | |

|

Study design |

|

|

|

|

| Cohort |

0.86 (0.67, 1.03) |

0.200 (33.1%) |

0.91 (0.65, 1.17) |

0.366 (0) |

| Case–control |

0.78 (0.59, 0.97) |

0.027 (60.4%) |

0.87 (0.70, 1.04) |

0.006 (60.9%) |

|

Gender |

|

|

|

|

| Male |

0.80 (0.66, 0.93) |

0.160 (35.1%) |

1.00 (0.69, 1.31) |

0.067 (58.1%) |

| Female |

0.68 (0.45, 0.91) |

0.247 (27.6%) |

1.51 (1.01, 2.00) |

0.364 (0) |

|

Geographical region |

|

|

|

|

| Europe |

0.79 (0.24, 1.34) |

0.040 (76.3%) |

0.65 (0.62, 1.09) |

0.138 (42.7%) |

| US/Canada |

0.83 (0.68, 0.98) |

0.047 (50.8%) |

0.94 (0.74, 1.13) |

0.047 (55.5%) |

| Japan |

0.76 (0.45, 1.27) |

- |

0.63 (0.38, 1.02) |

- |

|

Source of intake |

|

|

|

|

| Diet |

0.90 (0.80, 1.01) |

0.426 (0) |

0.87 (0.7, 1.04) |

0.007 (60.3%) |

| Supplement |

0.64 (0.47, 0.82) |

0.568 (0) |

0.80 (0.52, 1.23) |

- |

| Diet and supplement | 0.80 (0.49, 1.12) | 0.045 (62.7%) | 0.72 (0.43, 1.00) | 0.110 (54.8%) |

High versus low carotenoids intake or blood carotenoids levels

The pooled REs of bladder cancer for the highest versus lowest categories of carotenoids intake or blood carotenoids levels are presented in Table 3. High intake of total carotenoids, α-carotene, β-carotene, and β-cryptoxanthin was associated with a significantly lower risk of bladder cancer. The summary REs of bladder cancer comparing the highest with the lowest category of intake were 0.67 (95% CI 0.55, 0.79) for total carotenoids, 0.87 (95% CI 0.76, 0.99) for α-carotene, 0.89 (95% CI 0.82, 0.97) for β-carotene and 0.86 (95% CI 0.73, 1.00) for β-cryptoxanthin. No significant associations were found between lutein and zeaxanthin, or lycopene intake and the risk of bladder cancer. There was a significant reduction in bladder cancer risk associated with increasing blood level of total carotenoids (RE 0.43; 95% CI 0.55, 0.79), α-carotene (RE 0.56; 95% CI 0.37, 0.75), β-carotene (RE 0.41; 95% CI 0.05, 0.78), and lutein and zeaxanthin (RE 0.50; 95% CI 0.12, 0.87), whereas no significant association was observed for β-cryptoxanthin or lycopene.

Table 3.

Pooled risk estimates for the associations between carotenoids intake or blood carotenoids levels and bladder cancer risk

| Specific carotenoids | Number of studies | Pooled relative risk (95% CI) | Q-test for heterogeneity P value ( I 2 score) |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Carotenoids intake | |||

| Total carotenoids |

4 |

0.67 (0.55, 0.79) |

0.524 (0) |

| α-carotene |

8 |

0.87 (0.76, 0.99) |

0.221 (27.2%) |

| β-carotene |

12 |

0.89 (0.82, 0.97) |

0.084 (38.6%) |

| β-cryptoxanthin |

6 |

0.86 (0.73, 1.00) |

0.427(0) |

| Lutein/zeaxanthin |

6 |

0.93 (0.70, 1.17) |

0.035 (58.2%) |

| Lycopene |

6 |

0.95 (0.82, 1.07) |

0.54 (0) |

|

Blood carotenoids level | |||

| Total carotenoids |

2 |

0.43 (0.20, 0.93) |

0.241 (27.3%) |

| α-carotene |

4 |

0.56 (0.37, 0.75) |

0.106 (51.0%) |

| β-carotene |

4 |

0.41 (0.05, 0.78) |

0.013 (72.4%) |

| β-cryptoxanthin |

4 |

0.62 (0.06, 1.19) |

0.027 (67.4%) |

| Lutein/zeaxanthin |

4 |

0.50 (0.12, 0.87) |

0.056 (50.2%) |

| Lycopene | 4 | 0.60 (0.17, 1.03) | 0.053 (61.0%) |

Discussion

Although vitamin A is found in a wide variety of foods, many people do not obtain an adequate intake of this nutrient. Therefore, the impact of vitamin A intake on bladder cancer risk has important public health implications Our findings were inconsistent with the previous meta-analysis [6], which suggested that no increased risk of bladder cancer were found for diets low in retinol (RE 1.01; 95% CI 0.83, 1.23) or beta-carotene (RE 1.10; 95% CI 0.93, 1.30) intake. We conducted an updated meta-analysis with results from new epidemiological studies presented in the past 13 years, and excluded results not adjusted for age, sex, and smoking. We complemented this analysis with pooled analyses of each carotenoid and blood vitamin A levels. The present meta-analysis suggests that increased vitamin A intake is associated with a reduced risk of bladder cancer. Retinol intake had a weak, but non-significant inverse association with the risk of bladder cancer, and carotenoids intake had a strong inverse association with the risk of bladder cancer. Moreover, both the blood total retinol and carotenoids levels had a significant association with the reduced risk of bladder cancer.

A preventive role of vitamin A in the development of bladder cancer is plausible. Retinol, the physiologically active form of vitamin A, and its metabolites (retinoids) play an important role in cell proliferation and differentiation [35]. Synthetic retinoids are effective in the prevention of bladder carcinogenesis in experimental animals [36]. We found that high retinol intake was associated with a borderline significant reduced risk of bladder cancer, and the non-significance might be attributed to the heterogeneity among studies. The anticarcinogenic properties of carotenoids are associated with their antioxidant activities; their modulation of carcinogen metabolism; their effects on cell translation and differentiation, cell-to-cell communication and immune function; and their inhibition of cell proliferation, oncogene expression and the endogenous formation of carcinogens [37]. While some carotenoids have potential to form vitamin A (provitamin A carotenoids, including α-carotene, β-carotene, and β-cryptoxanthin), others do not have this capability (non-provitamin A carotenoids such as lycopene, lutein, and zeaxanthin) [38]. Our results showed a significantly reduced risk of bladder cancer with high intake of α-carotene, β-carotene, and β-cryptoxanthin, but no association with lycopene, lutein, and zeaxanthin, suggesting that provitamin As are responsible for the chemoprotective effects of vitamin A.

Interestingly, we found that the inverse associations between vitamin A and risk of bladder cancer were more evident in blood levels. This may be because of measurement error in the assessment of vitamin A intake from food frequency questionnaires, leading to an attenuation of the observed association. By measuring vitamin A in blood, researchers are able to estimate the internal doses of nutrients. However, blood level of vitamin A only reflects a short-term dietary intake because the half-life of vitamin A in blood is only a few days. In addition, many people make changes to their diet by increasing the intake of dietary vitamin A after a cancer diagnosis as a way of staying as healthy as possible, and blood levels of vitamin A should be higher than before the diagnosis. This would underestimate the true associations of vitamin A with bladder cancer and result in bias of the RE toward the null. Despite this potential limitation, we found strong inverse associations between blood levels of retinol and some carotenoids and bladder cancer, which indicated that our estimates are relatively conservative.

Heterogeneity is often a concern in a meta-analysis, and we found a significant heterogeneity for total vitamin A and retinol intake. This may be due to the inherent methodological differences, such as study design and different ranges of exposure among studies. Although most studies adjusted for known risk factors for bladder cancer (age, sex, and smoking), residual or unknown confounding cannot be excluded as a potential explanation for the observed heterogeneity. Also, some studies measured vitamin A intake from diet only, whereas other studies combined dietary and supplemental vitamin A intake. We used a random-effects model to try to mitigate the heterogeneity as an issue, and our sensitivity analyses did not change the results for total vitamin A and retinol intake. We further performed stratified analyses by study design, sex, geographical region, and source of intake. Nevertheless, results were similar for total vitamin A and retinol intake throughout the subgroups.

A major strength of our study is the large number of included participants (11,580), and this is the first report to pool REs of bladder cancer for each carotenoid. In addition, our results were based on the adjusted evaluation. However, several limitations should be mentioned. First, as a meta-analysis of epidemiological studies, a food-frequency questionnaire was used to estimate the vitamin A intake, which may be influenced by the recall and information bias. Second, the sample sizes for several strata in the subgroup analyses were relatively small, and these results should be interpreted with caution. Finally, publication bias could be of concern because small studies with null results tend not to be published, though we found no evidence of publication bias in the meta-analysis.

Conclusion

Our results support the hypothesis that diets high in vitamin A intake decrease the risk of bladder cancer. However, given these limitations and the heterogeneity of this meta-analysis, it is premature to recommend higher dietary vitamin A for the primary prevention of bladder cancer. Further investigation using large samples and a rigorous methodology is warranted.

Abbreviations

CI: confidence interval; RE: risk estimate.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

JT and RW wrote the manuscript; HZ and BY performed literature search and analyzed the data; YC performed statistical analysis; JT revised and edited the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Contributor Information

Jian-er Tang, Email: doctortangjianer@qq.com.

Rong-jiang Wang, Email: urowang@126.com.

Huan Zhong, Email: mymqq@aliyun.com.

Bing Yu, Email: urohdh@126.com.

Yu Chen, Email: nana.0109@aliyun.com.

References

- Ferlay J, Shin HR, Bray F, Forman D, Mathers C, Parkin DM. Estimates of worldwide burden of cancer in 2008: GLOBOCAN 2008. Int J Cancer. 2008;2010(127):2893–2917. doi: 10.1002/ijc.25516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sievert KD, Amend B, Nagele U, Schilling D, Bedke J, Horstmann M, Hennenlotter J, Kruck S, Stenzl A. Economic aspects of bladder cancer: what are the benefits and costs? World J Urol. 2009;27:295–300. doi: 10.1007/s00345-009-0395-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leppert JT, Shvarts O, Kawaoka K, Lieberman R, Belldegrun AS, Pantuck AJ. Prevention of bladder cancer: a review. Eur Urol. 2006;49:226–234. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2005.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeegers MP, Kellen E, Buntinx F, van den Brandt PA. The association between smoking, beverage consumption, diet and bladder cancer: a systematic literature review. World J Urol. 2004;21:392–401. doi: 10.1007/s00345-003-0382-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sporn MB, Roberts AB. Role of retinoids in differentiation and carcinogenesis. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1984;73:1381–1387. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinmaus CM, Nunez S, Smith AH. Diet and bladder cancer: a meta-analysis of six dietary variables. Am J Epidemiol. 2000;151:693–702. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a010264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DerSimonian R, Laird N. Meta-analysis in clinical trials. Control Clin Trials. 1986;7:177–188. doi: 10.1016/0197-2456(86)90046-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higgins JP, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, Altman DG. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ. 2003;327:557–560. doi: 10.1136/bmj.327.7414.557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egger M, Davey Smith G, Schneider M, Minder C. Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ. 1997;315:629–634. doi: 10.1136/bmj.315.7109.629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Risch HA, Burch JD, Miller AB, Hill GB, Steele R, Howe GR. Dietary factors and the incidence of cancer of the urinary bladder. Am J Epidemiol. 1988;127:1179–1191. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a114911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steineck G, Hagman U, Gerhardsson M, Norell SE. Vitamin A supplements, fried foods, fat and urothelial cancer. A case-referent study in Stockholm in 1985–87. Int J Cancer. 1990;45:1006–1011. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910450604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nomura AM, Kolonel LN, Hankin JH, Yoshizawa CN. Dietary factors in cancer of the lower urinary tract. Int J Cancer. 1991;48:199–205. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910480208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riboli E, Gonzalez CA, Lopez-Abente G, Errezola M, Izarzugaza I, Escolar A, Nebot M, Hemon B, Agudo A. Diet and bladder cancer in Spain: a multi-centre case–control study. Int J Cancer. 1991;49:214–219. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910490212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shibata A, Paganini-Hill A, Ross RK, Henderson BE. Intake of vegetables, fruits, beta-carotene, vitamin C and vitamin supplements and cancer incidence among the elderly: a prospective study. Br J Cancer. 1992;66:673–679. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1992.336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruemmer B, White E, Vaughan TL, Cheney CL. Nutrient intake in relation to bladder cancer among middle-aged men and women. Am J Epidemiol. 1996;144:485–495. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a008955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michaud DS, Spiegelman D, Clinton SK, Rimm EB, Willett WC, Giovannucci E. Prospective study of dietary supplements, macronutrients, micronutrients, and risk of bladder cancer in US men. Am J Epidemiol. 2000;152:1145–1153. doi: 10.1093/aje/152.12.1145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wakai K, Takashi M, Okamura K, Yuba H, Suzuki K, Murase T, Obata K, Itoh H, Kato T, Kobayashi M, Sakata T, Otani T, Ohshima S, Ohno Y. Foods and nutrients in relation to bladder cancer risk: a case–control study in Aichi Prefecture, Central Japan. Nutr Cancer. 2000;38:13–22. doi: 10.1207/S15327914NC381_3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeegers MP, Goldbohm RA, van den Brandt PA. Are retinol, vitamin C, vitamin E, folate and carotenoids intake associated with bladder cancer risk? Results from the Netherlands Cohort Study. Br J Cancer. 2001;85:977–983. doi: 10.1054/bjoc.2001.1968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michaud DS, Pietinen P, Taylor PR, Virtanen M, Virtamo J, Albanes D. Intakes of fruits and vegetables, carotenoids and vitamins A, E, C in relation to the risk of bladder cancer in the ATBC cohort study. Br J Cancer. 2002;87:960–965. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6600604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nomura AM, Lee J, Stemmermann GN, Franke AA. Serum vitamins and the subsequent risk of bladder cancer. J Urol. 2003;170:1146–1150. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000086040.24795.ad. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castelao JE, Yuan JM, Gago-Dominguez M, Skipper PL, Tannenbaum SR, Chan KK, Watson MA, Bell DA, Coetzee GA, Ross RK, Yu MC. Carotenoids/vitamin C and smoking-related bladder cancer. Int J Cancer. 2004;110:417–423. doi: 10.1002/ijc.20104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schabath MB, Grossman HB, Delclos GL, Hernandez LM, Day RS, Davis BR, Lerner SP, Spitz MR, Wu X. Dietary carotenoids and genetic instability modify bladder cancer risk. J Nutr. 2004;134:3362–3369. doi: 10.1093/jn/134.12.3362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holick CN, De Vivo I, Feskanich D, Giovannucci E, Stampfer M, Michaud DS. Intake of fruits and vegetables, carotenoids, folate, and vitamins A, C, E and risk of bladder cancer among women (United States) Cancer Causes Control. 2005;16:1135–1145. doi: 10.1007/s10552-005-0337-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hung RJ, Zhang ZF, Rao JY, Pantuck A, Reuter VE, Heber D, Lu QY. Protective effects of plasma carotenoids on the risk of bladder cancer. J Urol. 2006;176:1192–1197. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2006.04.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ozasa K, Ito Y, Suzuki K, Watanabe Y, Hayashi K, Mikami K, Nakao M, Miki T, Mori M, Sakauchi F, Washio M, Kubo T, Wakai K, Tamakoshi A. Japan Collaborative Cohort Study Group. Serum carotenoids and other antioxidative substances associated with urothelial cancer risk in a nested case–control study in Japanese men. J Urol. 2005;173:1502–1506. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000154614.58321.e6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kellen E, Zeegers M, Buntinx F. Selenium is inversely associated with bladder cancer risk: a report from the Belgian case–control study on bladder cancer. Int J Urol. 2006;13:1180–1184. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-2042.2006.01526.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Closas R, Garcia-Closas M, Kogevinas M, Malats N, Silverman D, Serra C, Tardon A, Carrato A, Castano-Vinyals G, Dosemeci M, Moore L, Rothman N, Sinha R. Food, nutrient and heterocyclic amine intake and the risk of bladder cancer. Eur J Cancer. 2007;43:1731–1740. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2007.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang D, Lin J, Grossman HB, Ma J, Wei B, Dinney CP, Wu X. Plasma vitamins E and A and risk of bladder cancer: a case–control analysis. Cancer Causes Control. 2008;19:981–992. doi: 10.1007/s10552-008-9165-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roswall N, Olsen A, Christensen J, Dragsted LO, Overvad K, Tjonneland A. Micronutrient intake and risk of urothelial carcinoma in a prospective Danish cohort. Eur Urol. 2009;56:764–770. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2009.06.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brinkman MT, Karagas MR, Zens MS, Schned A, Reulen RC, Zeegers MP. Minerals and vitamins and the risk of bladder cancer: results from the New Hampshire Study. Cancer Causes Control. 2010;21:609–619. doi: 10.1007/s10552-009-9490-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hotaling JM, Wright JL, Pocobelli G, Bhatti P, Porter MP, White E. Long-term use of supplemental vitamins and minerals does not reduce the risk of urothelial cell carcinoma of the bladder in the VITamins And Lifestyle study. J Urol. 2011;185:1210–1215. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2010.11.081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ros MM, Bueno-de-Mesquita HB, Kampman E, Aben KK, Büchner FL, Jansen EH, van Gils CH, Egevad L, Overvad K, Tjønneland A, Roswall N, Boutron-Ruault MC, Kvaskoff M, Perquier F, Kaaks R, Chang-Claude J, Weikert S, Boeing H, Trichopoulou A, Lagiou P, Dilis V, Palli D, Pala V, Sacerdote C, Tumino R, Panico S, Peeters PH, Gram IT, Skeie G, Huerta JM. et al. Plasma carotenoids and vitamin C concentrations and risk of urothelial cell carcinoma in the European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition. Am J Clin Nutr. 2012;96:902–910. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.111.032920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu JW, Cross AJ, Baris D, Ward MH, Karagas MR, Johnson A, Schwenn M, Cherala S, Colt JS, Cantor KP, Rothman N, Silverman DT, Sinha R. Dietary intake of meat, fruits, vegetables, and selective micronutrients and risk of bladder cancer in the New England region of the United States. Br J Cancer. 2012;106:1891–1898. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2012.187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park SY, Ollberding NJ, Woolcott CG, Wilkens LR, Henderson BE, Kolonel LN. Fruit and vegetable intakes are associated with lower risk of bladder cancer among women in the Multiethnic Cohort Study. J Nutr. 2013;143:1283–1292. doi: 10.3945/jn.113.174920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nutting CM, Huddart RA. Retinoids in the prevention of bladder cancer. Expert Rev Anticancer Ther. 2001;1:541–545. doi: 10.1586/14737140.1.4.541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moon RC, McCormick DL, Becci PJ, Shealy YF, Frickel F, Paust J, Sporn MB. Influence of 15 retinoic acid amides on urinary bladder carcinogenesis in the mouse. Carcinogenesis. 1982;3:1469–1472. doi: 10.1093/carcin/3.12.1469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson IT. IARC handbooks of cancer prevention volume 2: carotenoids and volume 3: vitamin A. Eur J Clin Nutr. 1999;53:830–834. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejcn.1600846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiseman M. The second World Cancer Research Fund/American Institute for Cancer Research expert report. Food, nutrition, physical activity, and the prevention of cancer: a global perspective. Proc Nutr Soc. 2008;67:253–256. doi: 10.1017/S002966510800712X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]