Abstract

The GRCh37.p13 primary assembly of the human genome contains 20805 protein coding mRNA, and 37147 non-protein coding genes and pseudogenes that as a result of RNA processing and editing generate 196501 gene transcripts. Given the size and diversity of the human transcriptome, it is timely to revisit what is known of VDR function in the regulation and targeting of transcription. Early transcriptomic studies using microarray approaches focused on the protein coding mRNA that were regulated by the VDR, usually following treatment with ligand. These studies quickly established the approximate size, and surprising diversity of the VDR transcriptome, revealing it to be highly heterogenous and cell type and time dependent. With the discovery of microRNA, investigators also considered VDR regulation of these non-protein coding RNA. Again, cell and time dependency has emerged. Attempts to integrate mRNA and miRNA regulation patterns are beginning to reveal patterns of co-regulation and interaction that allow for greater control of mRNA expression, and the capacity to govern more complex cellular events. As the awareness of the diversity of non-coding RNA increases, it is increasingly likely it will be revealed that VDR actions are mediated through these molecules also. Key knowledge gaps remain over the VDR transcriptome. The causes for the cell and type dependent transcriptional heterogenetiy remain enigmatic. ChIP-Seq approaches have confirmed that VDR binding choices differ very significantly by cell type, but as yet the underlying causes distilling VDR binding choices are unclear. Similarly, it is clear that many of the VDR binding sites are non-canonical in nature but again the mechanisms underlying these interactions are unclear. Finally, although alternative splicing is clearly a very significant process in cellular transcriptional control, the lack of RNA-Seq data centered on VDR function are currently limiting the global assessment of the VDR transcriptome. VDR focused research that complements publically available data (e.g., ENCODE Birney et al., 2007; Birney, 2012), TCGA (Strausberg et al., 2002), GTEx (Consortium, 2013) will enable these questions to be addressed through large-scale data integration efforts.

Keywords: VDR, microRNA, transcriptome, epigenetic, microarray

The transcriptional landscape of the human genome

An appreciation of the diversity of transcription across the human genome has undergone a rapid expansion in recent years, in large part thanks to the efforts of integrative genomic approaches such as those of ENCODE consortium (Birney, 2012; Maher, 2012; Stamatoyannopoulos, 2012; Rosenbloom et al., 2013). From these studies it has become apparent that there is considerable variation and diversity in; the distribution of transcription factor binding across the human genome; the interplay between transcription factors and different co-regulating partners; the extent of the genome that is transcribed; the number and functionally different RNA-based molecules that are transcribed, the impact of mechanisms that process and edit RNA molecules that generate even greater diversity of gene expression.

In this context it is timely to review the functions of the vitamin D receptor (VDR/NR1I1) (Pike et al., 1980; Baker et al., 1988; Carlberg and Campbell, 2013), and consider how its actions contribute to this diversity of transcriptional and post-transcriptional events.

The VDR acts in multimeric protein complexes to regulate transcription

The VDR, like many other members of the nuclear receptor superfamily are relatively well-understood transcription factors. Their actions have been dissected and modeled, and have generated the concept of cyclical gene regulation in which transcription factors oscillate between on and off states (Metivier et al., 2003; Reid et al., 2003; Kim et al., 2005; Vaisanen et al., 2005; Carroll et al., 2006; Meyer et al., 2006; Saramaki et al., 2006; Yang et al., 2006; Zella et al., 2006; Malinen et al., 2008; Seo et al., 2007).

A direct consequence of VDR genomic interactions and gene regulation is the control of the epigenetic states at receptor binding regions, and more broadly across target gene loci. Epigenetic events play a central role for transcriptional complexes and the various components in these multimeric complexes are able to initiate, sustain, and finally terminate transcription (Dobrzynski and Bruggeman, 2009). For example, different histone modifications can control the rate and magnitude of transcription (reviewed in Goldberg et al., 2007). These events are intertwined with levels of CpG methylation (Kangaspeska et al., 2008; Metivier et al., 2008; Le May et al., 2010). Thus the histone modifications regulated by VDR actions, and other epigenetic events including DNA methylation processes, combine during transcription to generate highly flexible chromatin states that are either transcriptionally receptive and resistant (Mohn and Schubeler, 2009). That is, the specific transcriptional potential of a gene is flexibly controlled by the combination of epigenetic events. These events are varied in space across the genomic loci, and in time through the course of the transcriptional cycle.

The diversity of histone modifications, and their association with different DNA functions formed the basis for the histone code hypothesis. This concept, first proposed in 1993, held that these modifications were governed in a coordinated manner and formed a code that mirrored the underlying DNA code to convey heritable information on transcription and expression (Turner, 1993). Given the rapid expansion of the understanding in the number of histone modifications, their genomic distribution and their combinatorial manner, it is only relatively recently that the true diversity of the range of histone states, and their functional outcomes, has become apparent (Goldberg et al., 2007). The strongest evidence that histone modifications at the level of meta-chromatin architecture form a stable and heritable “histone code,” is perhaps seen with X chromosome inactivation (reviewed in Turner, 1998). The extent to which similar processes operate to govern the activity of micro-chromatin contexts at gene promoter regions, is an area of debate (Jenuwein and Allis, 2001; Turner, 2002).

The regulation of transcription and the patterns of mRNA expression have been related to the expression of these histone modifications through a wide range of correlative and functional studies. For example, histone H3 lysine 4 tri-methylation (H3K4me3) is found in the promoter regions of actively transcribed genes. This mark is mutually exclusive with H3K9me, which instead is associated with transcriptionally silent promoter regions. Acetylation of H3K9 is found along with methylation of H3K4 at active promoter regions. Similarly, H3K27 can be either acetylated or methylated, with acetylation associated with active gene transcription and methylation associated with gene silencing.

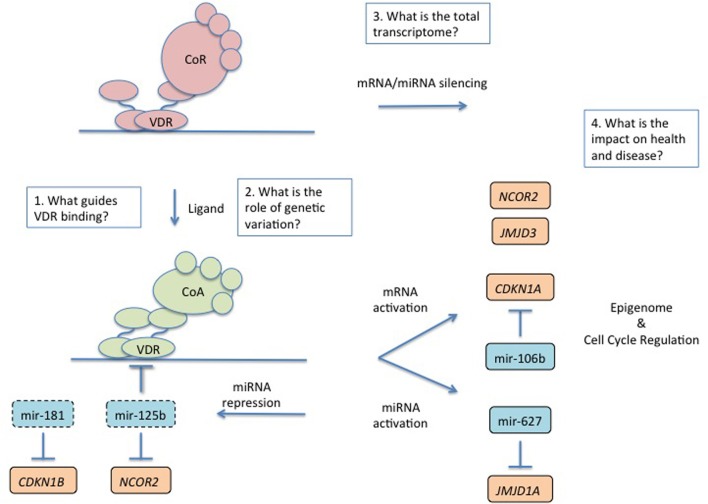

In many experimental cases it has been established that VDR activation by natural ligand 1α,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 (1α,25(OH)2D3) or synthetic analogs, can lead to a highly dynamic exchange of co-factors by releasing co-repressors and inducing a receptor conformation that attracts binding of co-activator proteins (Figure 1). This exchange of associations induces a more relaxed, or open, chromatin status and the recruitment of linking factors and subsequently the basal transcriptional machinery. However, this is not an indefinite signal and the ligand, is rapidly metabolized. Also the VDR itself is limited in function by proteasome-mediated receptor degradation (Peleg and Nguyen, 2010). In the absence of ligand, some basal level of receptor remains in the nucleus associated with co-repressor complex and leads to silencing of transcription (Malinen et al., 2008; Saramaki et al., 2009; Thorne et al., 2011; Doig et al., 2013). The sequencing, or choreography of these actions, give rise to the periodicity of transcriptional activation and pulsatile mRNA and protein accumulation and reflect intrinsic control mechanisms required to tightly regulate the expression of important signaling molecules. At closer resolution, for example on shorter time-scales, the patterns of regulation show some degree of coordinated pulsatile regulation, and probably reflect aspects of specific VDR binding sites impacting gene regulation for example through emerged to support chromatin looping within the same VDR target gene loci (Vaisanen et al., 2005; Saramaki et al., 2006, 2009).

Figure 1.

An overview of regulation and impact of the transcriptome by the nuclear VDR and the future challenges. The VDR toggles between a gene repressive and activating complex depending on the presence of ligand. Ligand activated gene regulated scenarios are most well understood. In the presense of ligand the VDR complex is associated with both mRNA and miRNA activation and there is clear evidence for co-regulation of these transcriptomes to tightly control final protein coding gene expression and phenotype. Ligand activated VDR also represses a number of miRNA for example including those that control expression of the VDR and components of the repressive complex. The major phenotypes associated with VDR control include cell cycle regulation and an emerging theme is the control of the epigenome. Four major questions remain in understanding VDR transcription. (1) What guides where the VDR binds in the genome? (2) What role does genetic variation in VDR binding sites play in changing the VDR transriptome? (3) What is the total VDR transcriptome? (4) What is the combined effect of the VDR transcriptome on health and disease and how can this be monitored and exploited?

Whilst these scenarios are relatively well characterized for the positive regulation of gene expression, it is probably not a complete understanding as the distribution of VDR binding in the genome (Ramagopalan et al., 2010; Heikkinen et al., 2011; Meyer et al., 2012; Ding et al., 2013) and the patterns of associated gene regulation suggest that the VDR is actually associated broadly with gene activation and repression. The mechanisms that drive gene repression appear more diverse than gene activation and reflect differences in complex formation, and the choreography of binding.

The patterns of protein-protein interaction identified for the VDR allude to both positive and negative gene regulation (Table 1). The VDR commonly forms a heterodimer with RXRα (Quack and Carlberg, 2000). However, the identification of partners that interact in the same complex supports a broad role for the VDR complex to regulate other signal transduction events and RNA processing activities.

Table 1.

Proteins known to interact with the VDR.

| Interacting protein | Function | Detection method | Interaction | Publication |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Retinoid X receptor alpha (RXRα) | Transcription factor | Electron microscopy | Direct interaction | Orlov et al., 2012 |

| Retinoid X receptor beta (RXRβ) | Transcription factor | Two hybrid | Physical association | Wang et al., 2011a |

| E1A-associated protein p300 (CBP/p300) | Histone acetyltransferase | Two hybrid | Physical association | Wang et al., 2011a |

| Mediator complex subunit (MED1) | Mediator complex that binds basal transcriptional machinery and drives transcriptional initiation | Pull down | Physical association | Yuan et al., 1998 |

| Nuclear receptor coactivator 6 (NCOA6) | Transcriptional coactivator of multiple nuclear receptors and other transcription factors | Two hybrid | Physical association | Mahajan and Samuels, 2000 |

| CXXC-type zinc finger protein 5 (CXXC5) | Transcription factor co-regulator of WNT signaling | Two hybrid | Physical association | Wang et al., 2011a |

| Tumor Protein P53 (p53) | Tumor suppressor protein containing transcriptional activation, DNA binding, and oligomerization domains | Fluorescence microscopy | Co-localization | Stambolsky et al., 2010 |

| Protein naked cuticle homolog 2 (NKD2) | Antagonist of WNT via degradation DVL | Two hybrid | Physical association | Wang et al., 2011a |

| SMAD family member 3 (SMAD3) | Transcriptional effector of TGFβ | Pull down | Physical association | Leong et al., 2001 |

| SNW Domain containing 1(SNW1) | Co-activator function with known roles as a splicing factor | Two hybrid | Physical association and co-localization | Baudino et al., 1998; Zhang et al., 2003 |

| SFRS protein kinase 1 (SRPK1) | Serine/arginine protein kinase specific for the SR (serine/arginine-rich domain) family of splicing factors | Protein kinase assay | Phosphorylation reaction | Varjosalo et al., 2013 |

| Protein kinase C substrate 80 K-H (PRKCSH) | Substrate for protein kinase C | Two hybrid | Physical association | Wang et al., 2011a |

| Protein-tyrosine phosphatase H1(PTPN3) | Protein tyrosine phosphatase that regulate a variety of cellular processes | Pull down | Physical association | Zhi et al., 2011 |

| Complement Factor H (CFH) | Regulator of complement activation (RCA) gene cluster and plays a role in the defense mechanism to microbial infections | Two hybrid | Physical association | Wang et al., 2011a |

| β-catenin | Dual function protein, regulating the coordination of cell–cell adhesion and gene transcription. | Co-localization | Functional interaction | Pálmer et al., 2001 |

| Prolylcarboxypeptidase (Angiotensinase C) (PRCP) | A lysosomal prolylcarboxypeptidase, which cleaves C-terminal amino acids linked to proline | Two hybrid | Physical association | Wang et al., 2011a |

| Cyclin D3 (CCND3) | Cyclin associated with control of cell cycle and known co-factor for several nuclear receptods | Two hybrid | Physical association | Wang et al., 2011a |

| Hair growth associated (HR) | Transcriptional corepressor of multiple nuclear receptors | Pull down | Direct interaction | Hsieh et al., 2003 |

| Nuclear corepressor 1 (NCOR1) | Transcriptional corepressor | Two hybrid | Physical association | Tagami et al., 1998 |

| Nuclear corepressor 2 (NCOR2) | Transcriptional corepressor | Immunoprecipitation | Physical association | Kim et al., 2009 |

| COP9 signalosome subunit 2 (COPS2) | Transcriptional corepressor and component of the ubiquitin conjugation pathway | Two hybrid | Physical association | Polly et al., 2000 |

The INTACT database curated by EBI http://www.ebi.ac.uk/intact/ was interrogated for interactions with the VDR. Interactions of VDR with NCOR1, NCOR2, and COPS2 were curated from the literature.

A number of proteins with transcriptional activator function have been identified in complex with VDR. For example, CBP/p300 is a transcriptional co-integrator with histone acetlyase activity (Wang et al., 2011a,b, 2013a) and is associated with the VDR. Other proteins such as SNW1/NCOA62 which has function as a transcriptional co-activator (Baudino et al., 1998), as well as other proteins that have more recently been characterized to have coativator function (CCND3) (Cenciarelli et al., 1999; Lazaro et al., 2002; Despouy et al., 2003; Sarruf et al., 2005). Similarly the corepressor HR is also identified by such protein-protein interactions (Hsieh et al., 2003).

Aside from these traditional roles to modulate transcriptional actions, there is evidence to support a wider range of actions for the VDR in the control of mRNA. The coactivator SNW1 also plays a role as a splicing factor. This latter function is also shared by another VDR interacting protein, namely SRPK1, which is a protein kinase that regulates the activity of various splicing factors (Hayes et al., 2006; Aubol et al., 2013). Other interactions allude to the cross-talk between the VDR and different signal transduction processes. For example, the VDR interacts with negative regulators of WNT signaling (NKD2) (Katoh and Katoh, 2007), substrates for PKC signaling (PRKCSH) (Gkika et al., 2004), p53 (Kommagani et al., 2006; Lambert et al., 2006; Maruyama et al., 2006; Saramaki et al., 2006; Ellison et al., 2008) and SMAD3 (Ding et al., 2013; Ito et al., 2013; Zerr et al., 2014). The VDR functionally interacts with a range of co-repressors such as NCOR1 (Saramaki et al., 2009; Doig et al., 2013), NCOR2/SMRT (Khanim et al., 2004; Gynther et al., 2011), TRIP15/ALIEN (Polly et al., 2000; Cui et al., 2009) and DREAM (Scsucova et al., 2005) but, interestingly, agnostic protein-protein interaction tools such as INTACT (Table 1) have not identified direct VDR co-repressor interactions. It is unclear why these proteins are not identified in such protein-protein screens, but may reflect an experimental artifact as a result of investigators using ligand stimulated VDR to capture interacting proteins.

The diversity of VDR-protein interactions is reflected by the distributions of genomic binding sites

To identify VDR binding sites through the genome several groups have now applied ChIP-Seq approaches in different human cell types including immortalized lymphoblastoids (Ramagopalan et al., 2010), hepatic stellate cells (Ding et al., 2013) and cancer cell lines representing monocytic leukemia (Heikkinen et al., 2011) and colon cancer (Meyer et al., 2012). These studies also differed in the time of cell exposure to 1α,25 (OH)2D3 ranging from 40 min to 36 h identify binding sites, on the order of hundreds to several thousands of different binding sites depending on time of treatment with 1α25(OH)2D3 and cell background, with longer treatment time points tending to be associated with more binding sites. However, as yet there are not uniform standards for the analyses of NGS data, and therefore it is likely that different analytical approaches are influencing the number and significance of the VDR enriched peaks identified.

These differences in treatment and analytical approaches aside, these VDR binding data sets reveals that fewer than 20% of the VDR binding sites are in common between the different cell types. These finding perhaps offers strong support for the concept that VDR transcription is extremely tailored in different cell types, presumably through interactions with either equal or more dominant co-factors that combine to determine its binding. Another important finding from these studies is that the canonical binding site for the VDR, termed the direct repeat (DR) spaced by 3 nucleotides (DR-3), which was identified by traditional biochemical approaches in candidate gene studies, appears to be the minority genomic element that directly binds the receptor. Fewer that 30% of genomic VDR binding sites contain a DR-3, although this number is increased following ligand treatment when there is increased enrichment for VDR binding to DR-3 elements (reviewed in Carlberg and Campbell, 2013). Nonetheless, a range of other genomic elements were enriched in VDR binding peaks suggesting that the VDR co-operates closely with other factors to associate with the genome, both in the absence and presence of ligand. Indeed, the study of Evans and co-workers in the hepatic stellate cells (Ding et al., 2013) and the work of Pike and co-workers in colon cancer cells (Meyer et al., 2012) both address this significant cross-talk of the VDR. In the case of the hepatic cells this is considered in the context of TGF® and in the case of colon cancer cells this is with TCF4, downstream of ®-catenin. Both of these studies therefore reflect the finding of VDR interactions with SMAD3 specifically, and more generally with regulators of WNT signaling (Table 1).

The hunt for pioneer factors to explain the diversity of VDR function

Together these ChIP-Seq studies suggest that the VDR combines with other proteins in a network of interactions, quite likely in a cell type specific manner, to participate in diverse gene regulatory networks. It remains to be established how targeted or stochastic this is. The variation observed in both the type and position of binding sites for the VDR, depending on cell phenotype and disease state, suggests it is directed, and at least will establish a paradigm for hypothesis testing concerning what directs the VDR to bind and participate in gene transcription. The specificity of VDR signaling may arise due to integration with other perhaps more dominant transcription factors. Again, for other nuclear receptors (e.g., AR and ER) the concept has emerged that receptor binding is guided by the actions of more dominant so-called pioneer factors including the Forkhead (FKH) family members (Lupien et al., 2008; Serandour et al., 2011; Sahu et al., 2013). Efforts to define the major pioneer factors for the VDR have proved to be less consistent between the different VDR ChIP-Seq studies and may reflect the biology of the VDR which, given that it exists in the nucleus both in the presence and absence of ligand, potentially is a more interactive protein such that a single dominant pioneer factor is not so deterministic.

Another approach to identify the interacting partners of the VDR has been to examine the gene networks it regulates and to cluster genes by known regulating transcription factors. Novershtern et al. (2011) measured the transcriptome profiles of a large number of hematopoietic stem cells, multiple progenitor states and terminally differentiated cell types. They found distinct regulatory circuits in both stem cells and differentiated cells, which implicated dozens of new regulators in hematopoiesis. They identified 80 distinct modules of tightly co-expressed genes in the hematopoietic system. One of these modules is expressed in granulocytes and monocytes and includes genes encoding enzymes and cytokine receptors that are essential for inflammatory responses. Major players in this module are VDR together with the factors CEBPα and SPI1/PU.1. This indicates that VDR works together with this small set of transcription factors, in order to regulate granulocyte and monocyte differentiation. It is reasonable to anticipate that such modules exist in multiple cell types but are guided by the tissue specific expression of such factors.

VDR regulation of the protein-coding transcriptome

Anti-proliferative effects of 1α,25(OH)2D3 have been demonstrated in a wide variety of cancer cell lines, including those from prostate, breast, and colon (Colston et al., 1982, 1989; Peehl et al., 1994; Campbell et al., 1997; Koike et al., 1997; Elstner et al., 1999; Welsh et al., 2002; Pálmer et al., 2003). Following on from these, VDR transcriptional studies were initially undertaken at the candidate level to identify processes by which the VDR mediated its cellular effects. These approaches identified of the gene encoding the 1α,25(OH)2D3 metabolizing enzyme CYP24A1 (Dwivedi et al., 2000; Anderson et al., 2003) and CDKN1A (encodes p21(waf1/cip1)) (Schwaller et al., 1995) as VDR targets. Subsequently, with the emergence of differential expression and membrane array technology, workers applied these wider screening approaches to identify multiple genes regulated by the VDR. For example, Freedman and colleagues applied differential expression approaches in the context of 1α,25(OH)2D3 induced myeloid differentiation and identified a number of cyclin dependent kinase inhibitors including CDKN1A and undertook functional confirmation studies to suggest the importance of the regulation of these targets to trigger myeloid differentiation (Liu et al., 1996). Others undertook so-called focused array technology whereby cDNA probes for selected genes involved in key biological processes or disease states were arranged on macro scale membrane arrays. Such arrays contained anywhere from several hundred to several thousand probes, and so were not genome-wide in terms of coverage but rather were candidate arrays often focused around specific pathways or disease states such as cancer. Despite the limitations, these approaches yielded important information supporting the links between VDR action and the regulation of growth and signaling (Savli et al., 2002). Similarly, first generation arrays chips, for example from Affymetrix which contained 4500 probes (Akutsu et al., 2001), also enabled sufficient genomic coverage to begin to define specific regulated gene networks. This particular study from White (Akutsu et al., 2001) and co-workers identified 38 genes that were responsive to 1α,25(OH)2D3 exposure, which represented approximately 1% of the transcriptome studied, and included GADD45A. These earlier studies already suggested at the footprint of the VDR dependent transcriptome (reviewed in Rid et al., 2013). In many ways these studies highlighted the heterogeneity of VDR actions that was to be identified subsequently by ChIP-Seq studies. This heterogeneity may in part reflect experimental conditions with very different cell line differences, and genuine tissue-specific differences of co-factor expression that alter the amplitude and periodicity of VDR transcriptional actions.

Even within this diversity there is some consistency on a certain targets and the biological actions they relate to, including cell cycle regulation (Akutsu et al., 2001; Pálmer et al., 2003; Eelen et al., 2004; Wang et al., 2005). A common anti-proliferative VDR function is associated with arrest at G0/G1 of the cell cycle, coupled with up-regulation of a number of cell cycle inhibitors. Candidate promoter characterization studies have demonstrated a series of VDR binding sites in the promoter/enhancer region of CDKN1A (Liu et al., 1996; Saramaki et al., 2006). By contrast the regulation of the related CDKI p27(kip1) is mechanistically enigmatic, and included translational regulation and enhanced mRNA translation, and attenuating degrading mechanisms (Hengst and Reed, 1996; Wang et al., 1996; Huang et al., 2004; Li et al., 2004). The up-regulation of p21(waf1/cip1) and p27(kip1) principally mediate G1 cell cycle arrest, but 1α,25(OH)2D3 has been shown to mediate a G2/M cell cycle arrest in a number of cancer cell lines via direct induction of GADD45A (Akutsu et al., 2001; Jiang et al., 2003; Khanim et al., 2004).

In the transition to genome wide understanding, workers applied more comprehensive array approaches to define VDR mRNA transcriptomes. For example, investigations of squamous cells (Lin et al., 2002; Wang et al., 2005) identified networks of genes that trigger the response to wounding, protease inhibition, secondary metabolite biosynthesis, cellular migration, and amine biosynthetic processes. Another approach has been to examine vitamin D sensitive and responsive isogenic cell pairs and undertake analyses to identify key networks that are critical for mediating antiproliferative sensitivity toward 1α25(OH)2D3. In this manner a critical role for TGF® signaling was again revealed, to associate with VDR antiproliferative sensitivity toward 1α25(OH)2D3 in breast cancer cell models (Towsend et al., 2006). Exploiting leukemia cell models with differential responsiveness toward 1α25(OH)2D3 triggered-differentiation (Tagliafico et al., 2006) identified that certain VDR transcriptional targets could distinguish the aggressiveness of the leukemia, again, focused around cell cycle and included MS4A3 which can modulate the phosphorylation of CDK2 and therefore exert control over the cell cycle. This concept of VDR sensitive vs. resistant models was also exploited in prostate cancer to identify the critical VDR transcriptional targets that mediate antiproliferative sensitivity and again also identified cell cycle and signal transduction components including GADD45A and MAPKAPK2 that were required to mediate the sensitivity of cells to 1α,25(OH)2D3. Furthermore, these studies examined the epigenetic basis for the transcriptionally inert state of these targets in resistant models (Rashid et al., 2001; Khanim et al., 2004).

Identification of the VDR-dependent transcriptome using microarray approaches is heavily dependent on a range of statistical and technical considerations (Do and Choi, 2006; Zhang et al., 2009) including hybridization variations and limitations, background effects, normalization procedures, the choice of statistical test to identify differentially expressed genes, which in turn relies on study design and the numbers of arrays and samples chosen for study. Many of these study components were only formally agreed upon with the establishment of the MIAME compliant protocols in 2001 (Brazma et al., 2001), and as these became accepted standards for journal publication these approaches became widespread through the biological community.

MIAME compliant array experiments are subsequently published in public archives, such as GEO (Barrett et al., 2005, 2013) and ArrayExpress at EMBL (Parkinson et al., 2007) and Stanford microarray database (Marinelli et al., 2008). These three repositories between them contain thousands of genome-wide microarray experiments, containing millions of individual microarrays. Mining these repositories reveals a range of experiments (not all published) where cells have been treated with 1α,25(OH)2D3 and other vitamin D compounds, and RNA effects studied between short time points (1–2 h) to several days (Table 2). Again, these studies have supported consistent themes in terms of the VDR-mediated control of cell cycle and signal transduction processes, the suppression of WNT and NF-κB, and the regulation of IGF1 signaling (Kovalenko et al., 2011), and integrated actions with TGF® signaling. A final area to emerge from these agnostic studies of the VDR transcriptome is the impact that 1α25(OH)2D3 exposure exerts on a range of chromatin remodeling components. Interestingly, NCOR2/SMRT appears to be a target of VDR signaling (Dunlop et al., 2004), and adds to the concept that VDR signaling is cyclical and based on the functions of various negative feedback loops. Similarly, KDM6B/JMJD3 is a histone H3 lysine demethylase and expression is induced by the activated VDR. In this manner, VDR action can feed-forward its own transcriptional program by promoting H3K9 acetylation and gene action (Pereira et al., 2011).

Table 2.

Publically available MIAME compliant microarray studies of VDR function.

| Experimental title/design | GEO series accession number | Publication |

|---|---|---|

| PROTEIN CODING MRNA | ||

| Vitamin D effect on bronchial smooth muscle cells | GSE5145 | Bosse et al., 2007 |

| Genome-wide analysis of vitamin D receptor (VDR) target genes in THP-1 monocytic leucemia cells | GSE27270 | Heikkinen et al., 2011 |

| Transcriptional effects of 1,25 dihydroxi-vitamin D3 physiological and supra-physiological concentrations in breast cancer organotypic culture | GSE27220 | |

| Analysis of vitamin D response element binding protein target genes reveals a role for vitamin D in osteoblast mTOR signaling | GSE22523 | Lisse et al., 2011 |

| Expression profiling of androgen receptor and vitamin D receptor mediated signaling in prostate cancer cells | GSE17461 | Wang et al., 2011b |

| Understanding vitamin D resistance using expression microarrays | GSE9867 | Costa et al., 2009 |

| Effects of TX527, a hypocalcemic vitamin D analog on human activated T lymphocytes | GSE23984 | Baeke et al., 2011 |

| Transcriptome profiling of genes regulated by RXR and its partners in monocyte-derived dendritic cells | GSE23073 | Szeles et al., 2010 |

| NON-PROTEIN CODING RNA | ||

| MicroRNA-22 upregulation by vitamin D mediates its protective action against colon cancer. | GSE34564 | Alvarez-Diaz et al., 2012 |

| miRNA profiling of androgen receptor and vitamin D receptor mediated signaling in prostate cancer cells | GSE23814 | Wang et al., 2013b |

| Identification of miRNAs regulated by vitamin D within primary human osteoblasts | GSE34144 | |

| Vitamin D and microRNA expression | GSE20122 | |

Given the number of arrays available, it is now timely to consider meta-analyses across the arrays to reveal common themes; this forward compatibility is one the key benefits of MIAME compliance. Meta-integration of array data has been shown to be surprisingly revealing in a range of studies. For example at the larger scale various workers have integrated multiple microarray data to reveal underlying patterns in the context of disease classification (Shah et al., 2009; Engreitz et al., 2011) but can also be applied to consider that specific phenotypes (Martinez-Climent et al., 2010; Rantala et al., 2010; Lai et al., 2014). It is therefore timely for these data to mined, and integrated with related nuclear receptor actions or other transcription factors that appear to co-operate with the VDR, for example SMADs.

VDR regulation of non-coding RNA species

The human genome project in many ways was a race to define the protein coding genes within the human genome. Bacterial artificial chromosomes (BAC) clones enabled relatively large pieces of DNA, upto 300 kb to be inserted for sequencing (Osoegawa et al., 2000). However, a key step in the initial alignment process was to leverage cDNA and EST libraries and therefore naturally steered workers to protein coding genes, and the significance and extent of non-protein coding RNA remained largely unexplored.

Although non-coding RNA forms were well described in terms of ribosomal function it was little understood beyond this. The interpretation of the human genome, and other large scale approaches to investigating chromosomal function (Consortium et al., 2007; Tress et al., 2007) all led to a growing awareness of the extent of non-coding RNA and at least suggested that their was an unknown. This uncertainty has been reflected in the debate within the biological community over the extent and roles of so-called Junk DNA (Kapranov and St Laurent, 2012; Doolittle, 2013). As a result researchers have considered roles for non-coding RNA in the regulation of cell function and have begun to examine the interplay between the at least 20 different types of different non-coding RNA (reviewed in Ling et al., 2013). Many of these RNA species are gene regulatory RNA and include microRNA (miRNA), long non-coding RNA (long ncRNA), whereas others are involved in the post-transcriptional modification of RNA for example small nucleolar RNA (snoRNA).

Workers have now principally examined miRNA regulation by the VDR and evidence has emerged to support a role for the VDR to control regulation. For example Studzinski and co-workers revisited the mechanistically enigmatic VDR-mediated control p27(kip1). They elegantly demonstrated a role for VDR to down-regulate miR181a, which when left unchecked degrades p27(kip1)(Wang et al., 2009) (Figure 1). Thus, indirectly, VDR activation elevates expression of p27(kip1), initiates cell cycle arrest and commits cells toward differentiation. These studies illuminated the earlier ones that suggested that p27(kip1) protein levels appeared to be regulated by a range of post-transcriptional mechanisms, such as enhanced mRNA translation, and attenuating degradative mechanisms (Hengst and Reed, 1996; Huang et al., 2004; Li et al., 2004). Similar integration of miRNA and mRNA was revealed to control the regulation of CDKN1A. Dynamic patterns of CDKN1A mRNA accumulation have been observed in various cell systems (Thorne et al., 2011). This is in part explained by the epigenetic state of different VDR binding sites on the CDKN1A promoter. However, VDR-dependent co-regulation of miR-106b also appears to modulate the precise timing of CDKN1A accumulation and expression of p21(waf1/cip1) in a feed-forward loop and determine the final extent of the cell cycle arrest. 1α,25(OH)2D3 regulates the DNA helicase MCM7 (Khanim et al., 2004) that encodes the miR-106b, in intron 13 of the MCM7 gene, and together these co-regulation processes control p21(waf1/cip1) through the balance of MCM7 and CDKN1A (Saramaki et al., 2006; Ivanovska et al., 2008) (Figure 1).

MicroRNA (miRNA) contribute negative regulatory aspects to normal gene regulation, for example as part of feed-forward loop motifs (Mangan and Alon, 2003; Mangan et al., 2006). The co-regulation of mRNA and miRNA in motifs that included feed forward structures appears quite common (Song and Wang, 2008; Gatfield et al., 2009; Ribas et al., 2009; Sun et al., 2009; Wang et al., 2009). Other established miRNA targets of the VDR include miR-627 (Padi et al., 2013) that in turn targets JMJD1A (another histone H3 lysine demethylase) miR-98 (Ting et al., 2013) and let-7a-2 (Guan et al., 2013). However, one of the more explored relationships between VDR and miRNA is the relationship between VDR and miR-125b. MiR-125b inhibits VDR (Mohri et al., 2009; Zhang et al., 2011) and in turn VDR can down-regulate miR-125b (Iosue et al., 2013; Zhou et al., 2014), and the other targets of miR-125b include NCOR2/SMRT (Yang et al., 2012) (itself a VDR target gene) suggesting multiple levels of co-regulation and interdependent relationship between the VDR, and the mRNA and miRNA transcriptomes, and the epigenome. Finally, it is interesting to note that altered levels of miRNA are associated with cancer states and progression risks and indeed miR-125b is associated with aggressive prostate cancer (Shi et al., 2011; Amir et al., 2013; Singh et al., 2014).

Beyond these candidate studies, a number of investigators have undertaken miRNA microarray analyses (Table 2) and these approaches have identified various networks, including the control of lipid metabolism and PPAR© function (Wang et al., 2013b). It is likely that with the increased application of array approaches and next gen sequencing approaches will identify the key networks downstream of the VDR miRnome. This is unfortunately a more challenging research question owing to the many-to-many nature of miRNA; a given miRNA target many mRNA, and a given mRNA may have many miRNA targeting it. Thus, the computational challenges to resolve these relationships are not insignificant. Together these findings suggest that co-regulated miRNA may form an integral part of VDR signaling to control gene expression.

Of the other types of non-coding RNA, their regulation by VDR remains far less explored. Recently the group of Bickle have begun to dissect VDR regulation of lncRNA in keratinocytes and identified a number of target lncRNA and in doing so have raised the curtain on new avenues of exploration (Jiang and Bikle, 2014).

Conclusions and future challenges for understanding the VDR transcriptome

What are the proteins, or processes that guide where the VDR binds in the genome?

It is unclear what key pioneer factors will be identified and if the VDR is in a strong relationship with a specific family of pioneer factors, in the same that the AR is profoundly influenced by the Forkhead family members. Indeed, the precise pioneer factor may even be tissue specific as also revealed for the AR (Pihlajamaa et al., 2014). This may reflect the fact the ligand activation of the VDR is more associated with re-distribution of the VDR through the genome, rather than triggering movement into the nucleus (as in the case of the classic steroid hormone receptors).

The specific epigenetic niche that characterizes the VDR binding may also be revealing of where and why the VDR binds to the genome. These analyses will require agnostic integration of multiple genomic data sets, for example histone modifications, transcription factor binding, chromatin conformation and transcriptomic data and application of machine learning approaches to reveal the significance of the underlying patterns, VDR binding and transcriptional activity. Whilst the VDR was not included in the ENCODE project, judicious choice of a cell line model for these studies, most likely a Tier 1 cell line from ENCODE, will enable leverage of a considerable volume of cistromic and epigenomic data to be combined with de novo VDR ChIP-Seq data. In this manner the question of how TGF® and/or WNT signaling interacts directly or indirectly with VDR binding can be addressed relatively easily.

Another major knowledge gap in VDR understanding concerns the spatial relationships between VDR binding and the control of transcription. It is clear that chromatin looping processes can transiently bring distal regulatory regions into physical proximity to the proximal regions of a gene and lead to dynamic gene expression (Saramaki et al., 2009). To transition from examination of looping of this process at a single locus using established binding sites to the genome wide investigation is technically and statistically very challenging. Again, ENCODE analyses may be useful here, as Chromatin Interaction Analysis by Paired-End Tag Sequencing (ChIA-PET) data are available for specific cell lines; for example using RNA-PolII in K562 cells and therefore VDR ChIP-Seq in these cells would again be able to leverage this data to begin to understand how the VDR distributes and loops across the genome.

What is the role of genetic variation in determining how and where the VDR binds?

Genetic variation exists throughout the genome and by definition is predominately in non-RNA coding regions. This realization has been the catalyst for examining how genetic variation impacts transcription factor binding and activity. Perhaps the most comprehensive integration of these concepts has been the development of the RegulomeDB tool (Boyle et al., 2012) which considers the impact of genetic variation on the function of all transcription factors analyzed by ENCODE. To date this question has not been seriously considered in terms of the VDR. A major hurdle to addressing this question is very large potential for Type 1 error owing to the large-scale data sets that need to be integrated, namely; all SNPs and those in linkeage disequilibrium that are significantly associated with disease in replicated studies and all binding sites for a given transcription factor against the backdrop of the number of SNPs for a given trait, the platform used for identification and the total number of SNPs in the human genome. In the context of the VDR specifically, this challenge is compounded by the fact that the majority of VDR binding sites through the genome do not contain a canonical DR3 type binding element and therefore a critical question will remain around what protein is the VDR interacting with in the genomic context and how is this influenced by genetic variation. This challenge is clearly intertwined with developing a comprehensive knowledge of how the VDR binds to the genome.

What is the complete VDR transcriptome and how does it differ by tissue and by disease?

Surprisingly, no RNA-Seq data are yet available for the VDR. Therefore to capture all RNA regulated by the VDR will require RNA-Seq approaches applied to libraries that capture short and long RNA species. The ENCODE consortium have undertaken over 400 RNA-Seq experiments focused on different RNA species in multiple cell models, and this makes a compelling case for exploiting these data, especially in Tier 1 or Tier 2 cell lines. For example undertaking VDR ChIP-Seq and a limited number of RNA-Seq approaches in K562 cells has the potential to leverage a remarkable volume of data. Predictions from such integrative analyses could then be tested in other ENCODE resources, in RNA-Seq from multiple tissues in normal healthy donors, through the GTEx consortium, or through the vast numbers of microarrays that are publically available. For example, in the case of K562, which is a CML cell line, there are many large-scale microarray analyses of patients with CML to examine how the VDR transcriptome relates to disease state and drug response. A parallel outcome of investigating VDR function will be to address the role it plays in regulating splice variation as suggested by the interactions with proteins such as SNW1.

How will this knowledge be exploited in personalized measures of VDR system in health and disease?

Many aspects of the relationships identified above can be interpreted by serum borne measurements, which are highly attractive owing to their ease of measurement. Serum levels of the pro-hormone, 25(OH) vitamin D3, are strongly correlated with the generation of the active hormone 1α,25(OH)2D3 and VDR function. For example, reduced serum levels of 25(OH) vitamin D3 levels are associated with increased risk of either cancer initiation and/or progression (Drake et al., 2010; Shanafelt et al., 2011). Therefore the serum level of 25(OH) vitamin D3can yield the “potential” of the VDR system to signal (Brader et al., 2014). This potential is impacted by the various cellular mechanisms outlined above. Of these, genetic variation that impacts VDR binding can obviously be measured in any cell in the body. The total transcriptome can be challenging to measure but perhaps small non-coding RNA represent a highly attractive marker of activity. Remarkably, miRNA are readily secreted into serum where they remain stable (El-Hefnawy et al., 2004; Goyal et al., 2006; Taylor and Gercel-Taylor, 2008; Valadi et al., 2007) and can be reliably extracted and measured (Chen et al., 2008; Liu et al., 2008; Mitchell et al., 2008; Rabinowits et al., 2009). Using serum-borne molecules as prognostic markers is highly attractive for several reasons. First, they can overcome the limitations of inaccurate sampling for example in the case of the presence of cancer within a tumor biopsy. Second, they can encapsulate the effects of heterotypic cell interactions, again, for example within the tumor microenvironment. Third, they form a non-invasive test procedure. From a biostatistical perspective, given there are fewer miRNA than protein coding mRNA, genome-wide coverage is more readily achieved and avoids the statistical penalties typically associated mRNA genome wide testing (Lussier et al., 2012).

This raises the very exciting possibility that generating integrated models of VDR binding, the impact of genetic variation, the tissue specific differences in the transcriptome and identifying miRNA contained within transcriptional circuits offers the opportunity of exploiting their serum expression levels of 25(OH) vitamin D3, genetic variation and miRNA expression will be able to be exploited to predict accurately the capacity of VDR function.

Conflict of interest statement

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

Moray J. Campbell acknowledges support in part from National Institute of Health grants [R01 CA095367-06 and 2R01-CA-095045-06] and the NCI Cancer Center Support Grant to the Roswell Park Cancer Institute [CA016056].

References

- Akutsu N., Lin R., Bastien Y., Bestawros A., Enepekides D. J., Black M. J., et al. (2001). Regulation of gene Expression by 1alpha,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 and Its analog EB1089 under growth-inhibitory conditions in squamous carcinoma Cells. Mol. Endocrinol. 15, 1127–1139 10.1210/mend.15.7.0655 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alvarez-Diaz S., Valle N., Ferrer-Mayorga G., Lombardia L., Herrera M., Dominguez O., et al. (2012). MicroRNA-22 is induced by vitamin D and contributes to its antiproliferative, antimigratory and gene regulatory effects in colon cancer cells. Hum. Mol. Genet. 21, 2157–2165 10.1093/hmg/dds031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amir S., Ma A. H., Shi X. B., Xue L., Kung H. J., Devere White R. W. (2013). Oncomir miR-125b suppresses p14(ARF) to modulate p53-dependent and p53-independent apoptosis in prostate cancer. PLoS ONE 8:e61064 10.1371/journal.pone.0061064 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson P. H., O'Loughlin P. D., May B. K., Morris H. A. (2003). Quantification of mRNA for the vitamin D metabolizing enzymes CYP27B1 and CYP24 and vitamin D receptor in kidney using real-time reverse transcriptase- polymerase chain reaction. J. Mol. Endocrinol. 31, 123–132 10.1677/jme.0.0310123 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aubol B. E., Jamros M. A., McGlone M. L., Adams J. A. (2013). Splicing kinase SRPK1 conforms to the landscape of its SR protein substrate. Biochemistry 52, 7595–7605 10.1021/bi4010864 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baeke F., Korf H., Overbergh L., Verstuyf A., Thorrez L., Van Lommel L., et al. (2011). The vitamin D analog, TX527, promotes a human CD4+CD25highCD127low regulatory T cell profile and induces a migratory signature specific for homing to sites of inflammation. J. Immunol. 186, 132–142 10.4049/jimmunol.1000695 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker A. R., McDonnell D. P., Hughes M., Crisp T. M., Mangelsdorf D. J., Haussler M. R., et al. (1988). Cloning and expression of full-length cDNA encoding human vitamin D receptor. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 85, 3294–3298 10.1073/pnas.85.10.3294 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrett T., Suzek T. O., Troup D. B., Wilhite S. E., Ngau W. C., Ledoux P., et al. (2005). NCBI GEO: mining millions of expression profiles–database and tools. Nucleic Acids Res. 33, D562–D566 10.1093/nar/gki022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrett T., Wilhite S. E., Ledoux P., Evangelista C., Kim I. F., Tomashevsky M., et al. (2013). NCBI GEO: archive for functional genomics data sets–update. Nucleic Acids Res. 41, D991–D995 10.1093/nar/gks1193 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baudino T. A., Kraichely D. M., Jefcoat S. C., Jr., Winchester S. K., Partridge N. C., MacDonald P. N. (1998). Isolation and characterization of a novel coactivator protein, NCoA-62, involved in vitamin D-mediated transcription. J. Biol. Chem. 273, 16434–16441 10.1074/jbc.273.26.16434 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birney E. (2012). The making of ENCODE: lessons for big-data projects. Nature 489, 49–51 10.1038/489049a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birney E., Stamatoyannopoulos J. A., Dutta A., Guigo R., Gingeras T. R., Margulies E. H., et al. (2007). Identification and analysis of functional elements in 1% of the human genome by the ENCODE pilot project. Nature 447, 799–816 10.1038/nature05874 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bosse Y., Maghni K., Hudson T. J. (2007). 1alpha,25-dihydroxy-vitamin D3 stimulation of bronchial smooth muscle cells induces autocrine, contractility, and remodeling processes. Physiol. Genomics 29, 161–168 10.1152/physiolgenomics.00134.2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyle A. P., Hong E. L., Hariharan M., Cheng Y., Schaub M. A., Kasowski M., et al. (2012). Annotation of functional variation in personal genomes using RegulomeDB. Genome Res. 22, 1790–1797 10.1101/gr.137323.112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brader L., Rejnmark L., Carlberg C., Schwab U., Kolehmainen M., Rosqvist F., et al. (2014). Effects of a healthy Nordic diet on plasma 25-hydroxyvitamin D concentration in subjects with metabolic syndrome: a randomized, placebo-controlled trial (SYSDIET). Eur. J. Nutr. [Epub ahead of print]. 10.1007/s00394-014-0674-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brazma A., Hingamp P., Quackenbush J., Sherlock G., Spellman P., Stoeckert C., et al. (2001). Minimum information about a microarray experiment (MIAME)-toward standards for microarray data. Nat. Genet. 29, 365–371 10.1038/ng1201-365 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell M. J., Elstner E., Holden S., Uskokovic M., Koeffler H. P. (1997). Inhibition of proliferation of prostate cancer cells by a 19-nor-hexafluoride vitamin D3 analogue involves the induction of p21waf1, p27kip1 and E-cadherin. J. Mol. Endocrinol. 19, 15–27 10.1677/jme.0.0190015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlberg C., Campbell M. J. (2013). Vitamin D receptor signaling mechanisms: integrated actions of a well-defined transcription factor. Steroids 78, 127–136 10.1016/j.steroids.2012.10.019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carroll J. S., Meyer C. A., Song J., Li W., Geistlinger T. R., Eeckhoute J., et al. (2006). Genome-wide analysis of estrogen receptor binding sites. Nat. Genet. 38, 1289–1297 10.1038/ng1901 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cenciarelli C., De Santa F., Puri P. L., Mattei E., Ricci L., Bucci F., et al. (1999). Critical role played by cyclin D3 in the MyoD-mediated arrest of cell cycle during myoblast differentiation. Mol. Cell. Biol. 19, 5203–5217 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X., Ba Y., Ma L., Cai X., Yin Y., Wang K., et al. (2008). Characterization of microRNAs in serum: a novel class of biomarkers for diagnosis of cancer and other diseases. Cell Res. 18, 997–1006 10.1038/cr.2008.282 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colston K., Colston M. J., Fieldsteel A. H., Feldman D. (1982). 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 receptors in human epithelial cancer cell lines. Cancer Res. 42, 856–859 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colston K. W., Berger U., Coombes R. C. (1989). Possible role for vitamin D in controlling breast cancer cell proliferation. Lancet 1, 188–191 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Consortium E. P., Birney E., Stamatoyannopoulos J. A., Dutta A., Guigo R., Gingeras T. R., et al. (2007). Identification and analysis of functional elements in 1% of the human genome by the ENCODE pilot project. Nature 447, 799–816 10.1038/nature05874 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Consortium G. T. (2013). The Genotype-Tissue Expression (GTEx) project. Nat. Genet. 45, 580–585 10.1038/ng.2653 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costa J. L., Eijk P. P., van de Wiel M. A., ten Berge D., Schmitt F., Narvaez C. J., et al. (2009). Anti-proliferative action of vitamin D in MCF7 is still active after siRNA-VDR knock-down. BMC Genomics 10:499 10.1186/1471-2164-10-499 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cui M., Klopot A., Jiang Y., Fleet J. C. (2009). The effect of differentiation on 1,25 dihydroxyvitamin D-mediated gene expression in the enterocyte-like cell line, Caco-2. J. Cell. Physiol. 218, 113–121 10.1002/jcp.21574 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Despouy G., Bastie J. N., Deshaies S., Balitrand N., Mazharian A., Rochette-Egly C., et al. (2003). Cyclin D3 is a cofactor of retinoic acid receptors, modulating their activity in the presence of cellular retinoic acid-binding protein II. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 6355–6362 10.1074/jbc.M210697200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding N., Yu R. T., Subramaniam N., Sherman M. H., Wilson C., Rao R., et al. (2013). A vitamin D receptor/SMAD genomic circuit gates hepatic fibrotic response. Cell 153, 601–613 10.1016/j.cell.2013.03.028 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Do J. H., Choi D. K. (2006). Normalization of microarray data: single-labeled and dual-labeled arrays. Mol. Cells 22, 254–261 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dobrzynski M., Bruggeman F. J. (2009). Elongation dynamics shape bursty transcription and translation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 106, 2583–2588 10.1073/pnas.0803507106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doig C. L., Singh P. K., Dhiman V. K., Thorne J. L., Battaglia S., Sobolewski M., et al. (2013). Recruitment of NCOR1 to VDR target genes is enhanced in prostate cancer cells and associates with altered DNA methylation patterns. Carcinogenesis 34, 248–256 10.1093/carcin/bgs331 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doolittle W. F. (2013). Is junk DNA bunk? A critique of ENCODE. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 110, 5294–5300 10.1073/pnas.1221376110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drake M. T., Maurer M. J., Link B. K., Habermann T. M., Ansell S. M., Micallef I. N., et al. (2010). Vitamin D insufficiency and prognosis in non-Hodgkin's lymphoma. J. Clin. Oncol. 28, 4191–4198 10.1200/JCO.2010.28.6674 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunlop T. W., Vaisanen S., Frank C., Carlberg C. (2004). The genes of the coactivator TIF2 and the corepressor SMRT are primary 1alpha,25(OH)2D3 targets. J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 89–90, 257–260 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2004.03.079 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dwivedi P. P., Omdahl J. L., Kola I., Hume D. A., May B. K. (2000). Regulation of rat cytochrome P450C24 (CYP24) gene expression. Evidence for functional cooperation of Ras-activated Ets transcription factors with the vitamin D receptor in 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D(3)-mediated induction. J. Biol. Chem. 275, 47–55 10.1074/jbc.275.1.47 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eelen G., Verlinden L., Van Camp M., Mathieu C., Carmeliet G., Bouillon R., et al. (2004). Microarray analysis of 1alpha,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3-treated MC3T3-E1 cells. J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 89–90, 405–407 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2004.03.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Hefnawy T., Raja S., Kelly L., Bigbee W. L., Kirkwood J. M., Luketich J. D., et al. (2004). Characterization of amplifiable, circulating RNA in plasma and its potential as a tool for cancer diagnostics. Clin. Chem. 50, 564–573 10.1373/clinchem.2003.028506 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellison T. I., Smith M. K., Gilliam A. C., MacDonald P. N. (2008). Inactivation of the vitamin D receptor enhances susceptibility of murine skin to UV-induced tumorigenesis. J. Invest. Dermatol. 128, 2508–2517 10.1038/jid.2008.131 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elstner E., Campbell M. J., Munker R., Shintaku P., Binderup L., Heber D., et al. (1999). Novel 20-epi-vitamin D3 analog combined with 9-cis-retinoic acid markedly inhibits colony growth of prostate cancer cells. Prostate 40, 141–149 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0045(19990801)40:3%3C141::AID-PROS1%3E3.0.CO;2-C [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engreitz J. M., Chen R., Morgan A. A., Dudley J. T., Mallelwar R., Butte A. J. (2011). ProfileChaser: searching microarray repositories based on genome-wide patterns of differential expression. Bioinformatics 27, 3317–3318 10.1093/bioinformatics/btr548 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gatfield D., Le Martelot G., Vejnar C. E., Gerlach D., Schaad O., Fleury-Olela F., et al. (2009). Integration of microRNA miR-122 in hepatic circadian gene expression. Genes Dev. 23, 1313–1326 10.1101/gad.1781009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gkika D., Mahieu F., Nilius B., Hoenderop J. G., Bindels R. J. (2004). 80K-H as a new Ca2+ sensor regulating the activity of the epithelial Ca2+ channel transient receptor potential cation channel V5 (TRPV5). J. Biol. Chem. 279, 26351–26357 10.1074/jbc.M403801200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldberg A. D., Allis C. D., Bernstein E. (2007). Epigenetics: a landscape takes shape. Cell 128, 635–638 10.1016/j.cell.2007.02.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goyal A., Delves G. H., Chopra M., Lwaleed B. A., Cooper A. J. (2006). Prostate cells exposed to lycopene in vitro liberate lycopene-enriched exosomes. BJU Int. 98, 907–911 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2006.06434.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guan H., Liu C., Chen Z., Wang L., Li C., Zhao J., et al. (2013). 1,25-Dihydroxyvitamin D3 up-regulates expression of hsa-let-7a-2 through the interaction of VDR/VDRE in human lung cancer A549 cells. Gene 522, 142–146 10.1016/j.gene.2013.03.065 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gynther P., Toropainen S., Matilainen J. M., Seuter S., Carlberg C., Vaisanen S. (2011). Mechanism of 1alpha,25-dihydroxyvitamin D(3)-dependent repression of interleukin-12B. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1813, 810–818 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2011.01.037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes G. M., Carrigan P. E., Beck A. M., Miller L. J. (2006). Targeting the RNA splicing machinery as a novel treatment strategy for pancreatic carcinoma. Cancer Res. 66, 3819–3827 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-4065 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heikkinen S., Vaisanen S., Pehkonen P., Seuter S., Benes V., Carlberg C. (2011). Nuclear hormone 1alpha,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 elicits a genome-wide shift in the locations of VDR chromatin occupancy. Nucleic Acids Res. 39, 9181–9193 10.1093/nar/gkr654 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hengst L., Reed S. I. (1996). Translational control of p27Kip1 accumulation during the cell cycle. Science 271, 1861–1864 10.1126/science.271.5257.1861 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsieh J. C., Sisk J. M., Jurutka P. W., Haussler C. A., Slater S. A., Haussler M. R., et al. (2003). Physical and functional interaction between the vitamin D receptor and hairless corepressor, two proteins required for hair cycling. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 38665–38674 10.1074/jbc.M304886200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang Y. C., Chen J. Y., Hung W. C. (2004). Vitamin D(3) receptor/Sp1 complex is required for the induction of p27(Kip1) expression by vitamin D(3). Oncogene. 10.1038/sj.onc.1207621 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iosue I., Quaranta R., Masciarelli S., Fontemaggi G., Batassa E. M., Bertolami C., et al. (2013). Argonaute 2 sustains the gene expression program driving human monocytic differentiation of acute myeloid leukemia cells. Cell Death Dis. 4, e926 10.1038/cddis.2013.452 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ito I., Waku T., Aoki M., Abe R., Nagai Y., Watanabe T., et al. (2013). A nonclassical vitamin D receptor pathway suppresses renal fibrosis. J. Clin. Invest. 123, 4579–4594 10.1172/JCI67804 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ivanovska I., Ball A. S., Diaz R. L., Magnus J. F., Kibukawa M., Schelter J. M., et al. (2008). MicroRNAs in the miR-106b family regulate p21/CDKN1A and promote cell cycle progression. Mol. Cell. Biol. 28, 2167–2174 10.1128/MCB.01977-07 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jenuwein T., Allis C. D. (2001). Translating the histone code. Science 293, 1074–1080 10.1126/science.1063127 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang F., Li P., Fornace A. J., Jr., Nicosia S. V., Bai W. (2003). G2/M arrest by 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 in ovarian cancer cells mediated through the induction of GADD45 via an exonic enhancer. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 48030–48040 10.1074/jbc.M308430200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang Y. J., Bikle D. D. (2014). LncRNA: a new player in 1alpha, 25(OH)2 vitamin D3 /VDR protection against skin cancer formation. Exp. Dermatol. 23, 147–150 10.1111/exd.12341 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kangaspeska S., Stride B., Metivier R., Polycarpou-Schwarz M., Ibberson D., Carmouche R. P., et al. (2008). Transient cyclical methylation of promoter DNA. Nature 452, 112–115 10.1038/nature06640 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kapranov P., St Laurent G. (2012). Dark matter RNA: existence, function, and controversy. Front. Genet. 3:60 10.3389/fgene.2012.00060 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katoh M., Katoh M. (2007). WNT signaling pathway and stem cell signaling network. Clin. Cancer Res. 13, 4042–4045 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-2316 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khanim F. L., Gommersall L. M., Wood V. H., Smith K. L., Montalvo L., O'Neill L. P., et al. (2004). Altered SMRT levels disrupt vitamin D3 receptor signalling in prostate cancer cells. Oncogene 23, 6712–6725 10.1038/sj.onc.1207772 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim J. Y., Son Y. L., Lee Y. C. (2009). Involvement of SMRT Corepressor in Transcriptional Repression by the Vitamin D Receptor. Mol. Endocrinol. 23, 251–264 10.1210/me.2008-0426 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim S., Shevde N. K., Pike J. W. (2005). 1,25-Dihydroxyvitamin D3 stimulates cyclic vitamin D receptor/retinoid X receptor DNA-binding, co-activator recruitment, and histone acetylation in intact osteoblasts. J. Bone Miner. Res. 20, 305–317 10.1359/JBMR.041112 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koike M., Elstner E., Campbell M. J., Asou H., Uskokovic M., Tsuruoka N., et al. (1997). 19-nor-hexafluoride analogue of vitamin D3: a novel class of potent inhibitors of proliferation of human breast cell lines. Cancer Res. 57, 4545–4550 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kommagani R., Caserta T. M., Kadakia M. P. (2006). Identification of vitamin D receptor as a target of p63. Oncogene 25, 3745–3751 10.1038/sj.onc.1209412 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kovalenko P. L., Zhang Z., Yu J. G., Li Y., Clinton S. K., Fleet J. C. (2011). Dietary vitamin D and vitamin D receptor level modulate epithelial cell proliferation and apoptosis in the prostate. Cancer Prev. Res. (Phila.) 4, 1617–1625 10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-11-0035 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lai Y., Zhang F., Nayak T. K., Modarres R., Lee N. H., McCaffrey T. A. (2014). Concordant integrative gene set enrichment analysis of multiple large-scale two-sample expression data sets. BMC Genomics 15(Suppl. 1), S6 10.1186/1471-2164-15-S1-S6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lambert J. R., Kelly J. A., Shim M., Huffer W. E., Nordeen S. K., Baek S. J., et al. (2006). Prostate derived factor in human prostate cancer cells: gene induction by vitamin D via a p53-dependent mechanism and inhibition of prostate cancer cell growth. J. Cell. Physiol. 208, 566–574 10.1002/jcp.20692 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lazaro J. B., Bailey P. J., Lassar A. B. (2002). Cyclin D-cdk4 activity modulates the subnuclear localization and interaction of MEF2 with SRC-family coactivators during skeletal muscle differentiation. Genes Dev. 16, 1792–1805 10.1101/gad.U-9988R [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le May N., Mota-Fernandes D., Velez-Cruz R., Iltis I., Biard D., Egly J. M. (2010). NER factors are recruited to active promoters and facilitate chromatin modification for transcription in the absence of exogenous genotoxic attack. Mol. Cell 38, 54–66 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.03.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leong G. M., Subramaniam N., Figueroa J., Flanagan J. L., Hayman M. J., Eisman J. A., et al. (2001). Ski-interacting protein interacts with Smad proteins to augment transforming growth factor-beta-dependent transcription. J. Biol. Chem. 276, 18243–18248 10.1074/jbc.M010815200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li P., Li C., Zhao X., Zhang X., Nicosia S. V., Bai W. (2004). p27(Kip1) stabilization and G(1) arrest by 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D(3) in ovarian cancer cells mediated through down-regulation of cyclin E/cyclin-dependent kinase 2 and Skp1-Cullin-F-box protein/Skp2 ubiquitin ligase. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 25260–25267 10.1074/jbc.M311052200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin R., Nagai Y., Sladek R., Bastien Y., Ho J., Petrecca K., et al. (2002). Expression profiling in squamous carcinoma cells reveals pleiotropic effects of vitamin D3 analog EB1089 signaling on cell proliferation, differentiation, and immune system regulation. Mol. Endocrinol. 16, 1243–1256 10.1210/mend.16.6.0874 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ling H., Fabbri M., Calin G. A. (2013). MicroRNAs and other non-coding RNAs as targets for anticancer drug development. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 12, 847–865 10.1038/nrd4140 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lisse T. S., Liu T., Irmler M., Beckers J., Chen H., Adams J. S., et al. (2011). Gene targeting by the vitamin D response element binding protein reveals a role for vitamin D in osteoblast mTOR signaling. FASEB J. 25, 937–947 10.1096/fj.10-172577 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu C. G., Calin G. A., Volinia S., Croce C. M. (2008). MicroRNA expression profiling using microarrays. Nat. Protoc. 3, 563–578 10.1038/nprot.2008.14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu M., Lee M. H., Cohen M., Bommakanti M., Freedman L. P. (1996). Transcriptional activation of the Cdk inhibitor p21 by vitamin D3 leads to the induced differentiation of the myelomonocytic cell line U937. Genes Dev. 10, 142–153 10.1101/gad.10.2.142 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lupien M., Eeckhoute J., Meyer C. A., Wang Q., Zhang Y., Li W., et al. (2008). FoxA1 translates epigenetic signatures into enhancer-driven lineage-specific transcription. Cell 132, 958–970 10.1016/j.cell.2008.01.018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lussier Y. A., Stadler W. M., Chen J. L. (2012). Advantages of genomic complexity: bioinformatics opportunities in microRNA cancer signatures. J. Am. Med. Inform. Assoc. 19, 156–160 10.1136/amiajnl-2011-000419 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahajan M. A., Samuels H. H. (2000). A new family of nuclear receptor coregulators that integrate nuclear receptor signaling through CREB-binding protein. Mol. Cell. Biol. 20, 5048–5063 10.1128/MCB.20.14.5048-5063.2000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maher B. (2012). ENCODE: The human encyclopaedia. Nature 489, 46–48 10.1038/489046a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malinen M., Saramaki A., Ropponen A., Degenhardt T., Vaisanen S., Carlberg C. (2008). Distinct HDACs regulate the transcriptional response of human cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor genes to Trichostatin A and 1alpha,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3. Nucleic Acids Res. 36, 121–132 10.1093/nar/gkm913 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mangan S., Alon U. (2003). Structure and function of the feed-forward loop network motif. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 100, 11980–11985 10.1073/pnas.2133841100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mangan S., Itzkovitz S., Zaslaver A., Alon U. (2006). The incoherent feed-forward loop accelerates the response-time of the gal system of Escherichia coli. J. Mol. Biol. 356, 1073–1081 10.1016/j.jmb.2005.12.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marinelli R. J., Montgomery K., Liu C. L., Shah N. H., Prapong W., Nitzberg M., et al. (2008). The stanford tissue microarray database. Nucleic Acids Res. 36, D871–D877 10.1093/nar/gkm861 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez-Climent J. A., Fontan L., Fresquet V., Robles E., Ortiz M., Rubio A. (2010). Integrative oncogenomic analysis of microarray data in hematologic malignancies. Methods Mol. Biol. 576, 231–277 10.1007/978-1-59745-545-9_13 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maruyama R., Aoki F., Toyota M., Sasaki Y., Akashi H., Mita H., et al. (2006). Comparative genome analysis identifies the vitamin D receptor gene as a direct target of p53-mediated transcriptional activation. Cancer Res. 66, 4574–4583 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-2562 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Metivier R., Gallais R., Tiffoche C., Le Peron C., Jurkowska R. Z., Carmouche R. P., et al. (2008). Cyclical DNA methylation of a transcriptionally active promoter. Nature 452, 45–50 10.1038/nature06544 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Metivier R., Penot G., Hubner M. R., Reid G., Brand H., Kos M., et al. (2003). Estrogen receptor-alpha directs ordered, cyclical, and combinatorial recruitment of cofactors on a natural target promoter. Cell 115, 751–763 10.1016/S0092-8674(03)00934-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer M. B., Goetsch P. D., Pike J. W. (2012). VDR/RXR and TCF4/beta-catenin cistromes in colonic cells of colorectal tumor origin: impact on c-FOS and c-MYC gene expression. Mol. Endocrinol. 26, 37–51 10.1210/me.2011-1109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer M. B., Watanuki M., Kim S., Shevde N. K., Pike J. W. (2006). The human transient receptor potential vanilloid type 6 distal promoter contains multiple vitamin D receptor binding sites that mediate activation by 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 in intestinal cells. Mol. Endocrinol. 20, 1447–1461 10.1210/me.2006-0031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell P. S., Parkin R. K., Kroh E. M., Fritz B. R., Wyman S. K., Pogosova-Agadjanyan E. L., et al. (2008). Circulating microRNAs as stable blood-based markers for cancer detection. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 105, 10513–10518 10.1073/pnas.0804549105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohn F., Schubeler D. (2009). Genetics and epigenetics: stability and plasticity during cellular differentiation. Trends Genet. 25, 129–136 10.1016/j.tig.2008.12.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohri T., Nakajima M., Takagi S., Komagata S., Yokoi T. (2009). MicroRNA regulates human vitamin D receptor. Int. J. Cancer 125, 1328–1333 10.1002/ijc.24459 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Novershtern N., Subramanian A., Lawton L. N., Mak R. H., Haining W. N., McConkey M. E., et al. (2011). Densely interconnected transcriptional circuits control cell states in human hematopoiesis. Cell 144, 296–309 10.1016/j.cell.2011.01.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orlov I., Rochel N., Moras D., Klaholz B. P. (2012). Structure of the full human RXR/VDR nuclear receptor heterodimer complex with its DR3 target DNA. EMBO J. 31, 291–300 10.1038/emboj.2011.445 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osoegawa K., Tateno M., Woon P. Y., Frengen E., Mammoser A. G., Catanese J. J., et al. (2000). Bacterial artificial chromosome libraries for mouse sequencing and functional analysis. Genome Res. 10, 116–128 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Padi S. K., Zhang Q., Rustum Y. M., Morrison C., Guo B. (2013). MicroRNA-627 mediates the epigenetic mechanisms of vitamin D to suppress proliferation of human colorectal cancer cells and growth of xenograft tumors in mice. Gastroenterology 145, 437–446 10.1053/j.gastro.2013.04.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pálmer H. G., González-Sancho J. M., Espada J., Berciano M. T., Puig I., Baulida J., et al. (2001). Vitamin D(3) promotes the differentiation of colon carcinoma cells by the induction of E-cadherin and the inhibition of beta-catenin signaling. J. Cell. Biol. 154, 369–387 10.1083/jcb.200102028 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pálmer H. G., Sánchez-Carbayo M., Ordóñez-Morán P., Larriba M. J., Cordón-Cardó C, Muñoz A. (2003). Genetic signatures of differentiation induced by 1alpha,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 in human colon cancer cells. Cancer Res. 63, 7799–7806 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parkinson H., Kapushesky M., Shojatalab M., Abeygunawardena N., Coulson R., Farne A., et al. (2007). ArrayExpress–a public database of microarray experiments and gene expression profiles. Nucleic Acids Res. 35, D747–D750 10.1093/nar/gkl995 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peehl D. M., Skowronski R. J., Leung G. K., Wong S. T., Stamey T. A., Feldman D. (1994). Antiproliferative effects of 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 on primary cultures of human prostatic cells. Cancer Res. 54, 805–810 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peleg S., Nguyen C. V. (2010). The importance of nuclear import in protection of the vitamin D receptor from polyubiquitination and proteasome-mediated degradation. J. Cell. Biochem. 110, 926–934 10.1002/jcb.22606 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pereira F., Barbachano A., Silva J., Bonilla F., Campbell M. J., Munoz A., et al. (2011). KDM6B/JMJD3 histone demethylase is induced by vitamin D and modulates its effects in colon cancer cells. Hum. Mol. Genet. 20, 4655–4665 10.1093/hmg/ddr399 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pihlajamaa P., Sahu B., Lyly L., Aittomaki V., Hautaniemi S., Janne O. A. (2014). Tissue-specific pioneer factors associate with androgen receptor cistromes and transcription programs. EMBO J. 33, 312–326 10.1002/embj.201385895 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pike J. W., Gooze L. L., Haussler M. R. (1980). Biochemical evidence for 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D receptor macromolecules in parathyroid, pancreatic, pituitary, and placental tissues. Life Sci. 26, 407–414 10.1016/0024-3205(80)90158-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polly P., Herdick M., Moehren U., Baniahmad A., Heinzel T., Carlberg C. (2000). VDR-Alien: a novel, DNA-selective vitamin D(3) receptor-corepressor partnership. FASEB J. 14, 1455–1463 10.1096/fj.14.10.1455 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quack M., Carlberg C. (2000). The impact of functional vitamin D(3) receptor conformations on DNA-dependent vitamin D(3) signaling. Mol. Pharmacol. 57, 375–384 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rabinowits G., Gercel-Taylor C., Day J. M., Taylor D. D., Kloecker G. H. (2009). Exosomal microRNA: a diagnostic marker for lung cancer. Clin. Lung Cancer. 10, 42–46 10.3816/CLC.2009.n.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramagopalan S. V., Heger A., Berlanga A. J., Maugeri N. J., Lincoln M. R., Burrell A., et al. (2010). A ChIP-seq defined genome-wide map of vitamin D receptor binding: associations with disease and evolution. Genome Res. 20, 1352–1360 10.1101/gr.107920.110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rantala J. K., Edgren H., Lehtinen L., Wolf M., Kleivi K., Vollan H. K., et al. (2010). Integrative functional genomics analysis of sustained polyploidy phenotypes in breast cancer cells identifies an oncogenic profile for GINS2. Neoplasia 12, 877–888 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rashid S. F., Moore J. S., Walker E., Driver P. M., Engel J., Edwards C. E., et al. (2001). Synergistic growth inhibition of prostate cancer cells by 1 alpha,25 Dihydroxyvitamin D(3) and its 19-nor-hexafluoride analogs in combination with either sodium butyrate or trichostatin A. Oncogene 20, 1860–1872 10.1038/sj.onc.1204269 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reid G., Hubner M. R., Metivier R., Brand H., Denger S., Manu D., et al. (2003). Cyclic, proteasome-mediated turnover of unliganded and liganded ERalpha on responsive promoters is an integral feature of estrogen signaling. Mol. Cell 11, 695–707 10.1016/S1097-2765(03)00090-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ribas J., Ni X., Haffner M., Wentzel E. A., Salmasi A. H., Chowdhury W. H., et al. (2009). miR-21: an androgen receptor-regulated microRNA that promotes hormone-dependent and hormone-independent prostate cancer growth. Cancer Res. 69, 7165–7169 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-1448 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rid R., Wagner M., Maier C. J., Hundsberger H., Hintner H., Bauer J. W., et al. (2013). Deciphering the calcitriol-induced transcriptomic response in keratinocytes: presentation of novel target genes. J. Mol. Endocrinol. 50, 131–149 10.1530/JME-11-0191 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenbloom K. R., Sloan C. A., Malladi V. S., Dreszer T. R., Learned K., Kirkup V. M., et al. (2013). ENCODE data in the UCSC genome browser: year 5 update. Nucleic Acids Res. 41, D56–D63 10.1093/nar/gks1172 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sahu B., Laakso M., Pihlajamaa P., Ovaska K., Sinielnikov I., Hautaniemi S., et al. (2013). FoxA1 specifies unique androgen and glucocorticoid receptor binding events in prostate cancer cells. Cancer Res. 73, 1570–1580 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-12-2350 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saramaki A., Banwell C. M., Campbell M. J., Carlberg C. (2006). Regulation of the human p21(waf1/cip1) gene promoter via multiple binding sites for p53 and the vitamin D3 receptor. Nucleic Acids Res. 34, 543–554 10.1093/nar/gkj460 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]