Abstract

Background

Molecular clock methodologies allow for the estimation of divergence times across a variety of organisms; this can be particularly useful for groups lacking robust fossil histories, such as microbial eukaryotes with few distinguishing morphological traits. Here we have used a Bayesian molecular clock method under three distinct clock models to estimate divergence times within oomycetes, a group of fungal-like eukaryotes that are ubiquitous in the environment and include a number of devastating pathogenic species. The earliest fossil evidence for oomycetes comes from the Lower Devonian (~400 Ma), however the taxonomic affinities of these fossils are unclear.

Results

Complete genome sequences were used to identify orthologous proteins among oomycetes, diatoms, and a brown alga, with a focus on conserved regulators of gene expression such as DNA and histone modifiers and transcription factors. Our molecular clock estimates place the origin of oomycetes by at least the mid-Paleozoic (~430-400 Ma), with the divergence between two major lineages, the peronosporaleans and saprolegnialeans, in the early Mesozoic (~225-190 Ma). Divergence times estimated under the three clock models were similar, although only the strict and random local clock models produced reliable estimates for most parameters.

Conclusions

Our molecular timescale suggests that modern pathogenic oomycetes diverged well after the origin of their respective hosts, indicating that environmental conditions or perhaps horizontal gene transfer events, rather than host availability, may have driven lineage diversification. Our findings also suggest that the last common ancestor of oomycetes possessed a full complement of eukaryotic regulatory proteins, including those involved in histone modification, RNA interference, and tRNA and rRNA methylation; interestingly no match to canonical DNA methyltransferases could be identified in the oomycete genomes studied here.

Keywords: Oomycetes, Divergence times, Bayesian inference, Molecular clock, Gene expression regulation

Background

Eukaryotic diversity is primarily microbial, with multicellularity restricted to a few distinct lineages (plants, animals, fungi, and some algae). While the Proterozoic fossil record contains an abundance of organic-walled, often ornamented, microfossils interpreted as eukaryotes, evidence for the origins and diversification of specific lineages of microbial eukaryotes is rare, especially for those groups with few diagnostic morphological characters [1]. Molecular clock methods therefore provide the only avenue for elucidating the evolutionary history of some lineages. With the recognition that a single rate (“strict”) molecular clock as originally proposed by Zuckerkandl and Pauling [2,3] was often inadequate in light of rate variation among organisms, early studies suggested the use of local clocks or the removal of lineages that violated the assumption of rate homogeneity (reviewed in [4]). The continued development of molecular clock methodologies over the past two decades has allowed for the estimation of divergence times under more complex models of rate variation. Initial “relaxed clock” methods, such as non-parametric rate smoothing [5] and penalized likelihood [6], allowed rates to vary but sought to minimize large differences between parent and descendent branches. Additionally, Bayesian relaxed clock methods allow rates to vary among lineages but assume autocorrelation by drawing the rate of a descendent branch from a distribution whose mean is determined by the rate of the parent branch [7,8]; other Bayesian methods relax this assumption of autocorrelation for the co-estimation of phylogeny and divergence times [9]. Most recently, a random local clock model approach has been proposed which allows rate changes to occur along any branch in a phylogeny; this method allows users to directly test various local clock scenarios against a strict clock model of no rate changes [10].

In addition to improved modeling of rate variation, newer molecular clock methods are also able to better incorporate calibration uncertainty into the estimation of divergence times. Early methods treated fossil calibrations as fixed points (from which rates were derived); newer methods utilize probability distributions to better reflect the paleontological uncertainty of a fossil’s phylogenetic position in relation to modern organisms [11,12], as well as variance around the numerical age of geologic formations. However, some authors have already shown that modeling fossil probability distributions under different assumptions can have significant impacts on divergence time estimation [13], illustrating that rate calibration is still an important source of potential error in molecular clock studies.

In this study we have focused on the fungal-like oomycetes (Peronosporomycetes sensu[14]), a group of heterotrophic eukaryotes closely related to diatoms, brown algae, and other stramenopiles [15]. A close relationship among stramenopiles, alveolates, and several photosynthetic eukaryotes with red algal-derived plastids was previously suggested as the supergroup Chromalveolata [16]. However molecular studies have supported a grouping of stramenopiles and alveolates with the non-photosynthetic rhizarians (“SAR” sensu[17]), excluding other photosynthetic lineages; the recently revised eukaryote classification has now formalized the Sar supergroup [18]. Many oomycetes are saprotrophic in aquatic and terrestrial ecosystems, however several devastating pathogens are known, such as Phytophthora infestans, the causal agent of late blight in solanaceous plant hosts [19]. Some orders are primarily pathogenic, such as the Peronosporales and Albuginales, while others are composed of both pathogenic and saprotrophic members, such as the Pythiales, Saprolegniales, Leptomitales, and Rhipidiales [20]. Several basal lineages, such as the Eurychasmales and Haliphthorales, are known primarily as pathogens of marine algae and crustaceans, leading some to suggest that the oomycetes may be “hard-wired” for pathogenic lifestyles [15].

The earliest robust fossil evidence of oomycetes comes from the Lower Devonian (Pragian, ~408 Ma) Rhynie Chert [21]. Thick-walled, ornamented structures interpreted as oogonium-antheridium complexes [22], as well as thin-walled polyoosporous oogonia [23], are well preserved in association with degraded plant debris and cyanobacteria-dominated microbial mats. More recent oomycete fossils occur in the Carboniferous, where evidence for endophytic [24] and perhaps parasitic [25,26] interactions with plant hosts is more compelling. Additionally, the fossil species Combresomyces cornifer originally described from Lower Carboniferous chert in central France [27] has also been identified in Middle Triassic silicified peat from Antarctica [28], providing an intriguing example of geographic range and morphological stasis over roughly 90 million years of oomycete evolution [29].

This is the first study to estimate divergence times within the oomycetes using molecular clock methods. Previous studies have typically included a single representative within a larger study of eukaryotic evolution [30-32], or have used oomycetes to root the analysis [33,34]. As there is little a priori information on the tempo of evolution within oomycetes, here we estimate divergence times under three distinct molecular clock models: a single-rate strict clock, a relaxed clock with uncorrelated rates modeled under a lognormal distribution (UCLD), and a random local clock model. The availability of several complete genome sequences for oomycetes, diatoms, and a brown alga allowed us to carefully curate a dataset of 40 orthologs for divergence time estimation; we chose to focus on known regulators of eukaryotic gene expression to investigate their presence and level of conservation within pathogenic oomycetes. While the performance of the three models differed, the estimated divergence times suggested that oomycetes diverged from other stramenopiles by at least the mid-Paleozoic, and that two major lineages, the peronosporaleans and saprolegnialeans, diverged in the early Mesozoic, approximately 200 Ma after the first appearance of oomycetes in the fossil record.

Results

Regulators of gene expression in oomycetes

Complete genome sequences from eighteen species were examined (Table 1). A total of 70 genes involved in the regulation of gene expression were examined for homology in Phytophthora infestans (Table 2); homologs of two genes (Drosha-like; TFIIH, Ssl1 subunit) could not be identified in P. infestans but were present in other oomycetes. In general, oomycetes possess a full complement of canonical transcription factors and genes involved in chromatin modification, including multiple histone acetyltransferases, deacetylases, and methyltransferases (Table 2). Proteins known to be involved in post-transcriptional gene silencing [35] were identified in our search, including homologs of Argonaut, Dicer, RNA-dependent RNA polymerase, double-stranded RNA binding proteins, and an RNaseIII-domain containing protein (Table 2). A recent study has shown that these genes are expressed and functional in P. infestans[36]. However, unlike the previous study, we were able to identify a second Dicer-like homolog in the genomes of other oomycetes that is absent in P. infestans; these sequences showed more similarity to human and Drosophila Drosha proteins than to other Dicer homologs (data not shown). Two distinct groups of Argonaut proteins were identified in the oomycetes, as well as two types of double-stranded RNA binding proteins (Table 2). While no homologs to canonical eukaryotic DNA methyltransferases could be identified, a homolog of DNA methyltransferase 1-associated protein was present in all the genomes analyzed here. Several genes involved in RNA methylation were also found (Table 2).

Table 1.

Species with complete genome sequences included in this study

| Species | Strain/version | Genome source | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Achlya hypogyna |

ATCC48635 |

unpublished data |

(unpublished) |

|

Albugo laibachii |

Nc14 |

NCBI BLAST (http://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov) |

[37] |

|

Ectocarpus siliculosus |

Ec32 |

BOGAS (http://bioinformatics.psb.ugent.be) |

[38] |

|

Fragilariopsis cylindrus |

CCMP1102 v1.0 |

DOE-Joint Genome Institute (http://www.jgi.doe.gov) |

(unpublished) |

|

Hyaloperonospora arabidopsis |

Emoy2 v8.3.2 |

Virginia Bioinformatics Institute (http://www.vbi.vt.edu) |

[39] |

|

Phaeodactylum tricornutum |

CCAP1055/1 v2.0 |

DOE-Joint Genome Institute (http://www.jgi.doe.gov) |

[40] |

|

Phytophthora capsici |

LT1534 v11.0 |

DOE-Joint Genome Institute (http://www.jgi.doe.gov) |

[41] |

|

Phytophthora cinnamomi |

v1.0 |

DOE-Joint Genome Institute (http://www.jgi.doe.gov) |

(unpublished) |

|

Phytophthora infestans |

T30-4 |

Broad Institute (http://www.broadinstitute.org) |

[42] |

|

Phytophthora parasitica |

INRA-310 |

Broad Institute (http://www.broadinstitute.org) |

(unpublished) |

|

Phytophthora ramorum |

Pr-102 v1.1 |

DOE-Joint Genome Institute (http://www.jgi.doe.gov) |

[43] |

|

Phytophthora sojae |

P6497 v3.0 |

DOE-Joint Genome Institute (http://www.jgi.doe.gov) |

[43] |

|

Pseudo-nitzschia multiseries |

CLN-47 v1.0 |

DOE-Joint Genome Institute (http://www.jgi.doe.gov) |

(unpublished) |

|

Pythium ultimum |

BR144 v4.0 |

Pythium Genome Database (http://pythium.plantbiology.msu.edu) |

[44] |

|

Saprolegnia parasitica |

CBS223.65 |

Broad Institute (http://www.broadinstitute.org) |

[45] |

|

Tetrahymena thermophila |

SB210 v2008 |

Tetrahymena Genome Database (http://ciliate.org) |

[46] |

|

Thalassiosira pseudonana |

CCMP1335 v3.0 |

DOE-Joint Genome Institute (http://www.jgi.doe.gov) |

[47] |

| Thraustotheca clavata | ATCC34112 | unpublished data | (unpublished) |

Table 2.

Conserved regulators of gene expression evaluated for divergence time analysis

| Gene | Domains a | Reference b |

|---|---|---|

|

Chromatin modification |

|

|

| Anti-silencing factor Asf1 |

asf1 |

PITG_17091 |

| Brahma-like |

HAS, SNF2 N-terminal, Helicase conserved C-terminal, Bromodomain |

PITG_19037 |

| Chromodomain-containing protein (A) |

2x Chromo, SNF2 N-terminal, Helicase conserved C-terminal |

PITG_15837 |

| Chromodomain-containing protein (B) |

[PDZ, QLQ], 2x Chromo, SNF2 N-terminal, Helicase conserved C-terminal, PHD-finger, PHD-like (zf-HC5HC2H_2) |

PITG_10083 |

| Chromodomain-containing protein (C) |

PHD-finger, 2x Chromo, SNF2 N-terminal, Helicase conserved C-terminal |

PITG_00140 |

| Chromodomain-containing protein (D) |

[Chromo], Bromodomain, PHD, Chromo, [PDZ], SNF2 N-terminal, Helicase conserved C-terminal, PHD, [PHD], PHD-like (zf-HC5HC2H), PHD |

PITG_03401 |

| CXXC zinc finger containing protein |

[SNF2 N-terminal], 2x CXXC zinc finger, [FHA] |

PITG_03547 |

| DNA methyltransferase 1-associated protein |

[DNA methyltransferase 1-associated protein] |

PITG_15785 |

| ESA1-like histone acetyltransferase |

Tudor-knot RNA binding, MOZ/SAS |

PITG_01456 |

| GCN5-like histone acetyltransferase |

GNAT Acetyltransferase, Bromodomain |

PITG_20197 |

| HAT1-like histone acetyltransferase |

HAT1 N-terminus, [GNAT Acetyltransferase] |

PITG_00186 |

| KAT11 domain histone acetyltransferase (A) |

TAZ zinc finger, Bromodomain, [PHD], KAT11, ZZ zinc finger, TAZ zinc finger |

PITG_07302 |

| KAT11 domain histone acetyltransferase (B) |

[TAZ, TAZ], Bromodomain, [DUF902], [PHD], KAT11, [ZZ, TAZ] |

PITG_06533 |

| KAT11 domain histone acetyltransferase (C) |

Bromodomain, [PHD], KAT11 |

PITG_18027 |

| KAT11 domain histone acetyltransferase (D) |

Bromodomain, KAT11 |

PITG_08587 |

| Histone deacetylase HDA1 |

histone deacetylase |

PITG_01897 |

| Histone deacetylase HDA2 |

[ankyrin repeats], histone deacetylase |

PITG_08237 |

| Histone deacetylase HDA4 |

histone deacetylase |

PITG_05176 |

| Histone deacetylase HDA5 |

histone deacetylase |

PITG_15415 |

| Histone deacetylase HDA6 |

histone deacetylase |

PITG_21309 |

| Histone deacetylase HDA7 |

histone deacetylase |

PITG_12962 |

| Histone deacetylase HDA8 |

histone deacetylase |

PITG_01911 |

| Histone deacetylase HDA9 |

histone deacetylase |

PITG_04499 |

| DOT1-like histone methyltransferase |

DOT1 |

PITG_00145 |

| Histone-lysine N-methyltransferase |

Bromodomain, PHD-like zinc-binding (zf-HC5HC2H), F/Y-rich N-terminus, SET |

PITG_20502, PITG_04185 |

| Protein methyltransferase w/bicoid |

Methyltransferase, bicoid-interacting protein 3 |

PITG_14915 |

| SLIDE domain-containing protein (A) |

DUF1898, SNF2 N-terminal, Helicase conserved C-terminal, SLIDE, [myb-like DNA-binding], HMG box |

PITG_02286 |

| SLIDE domain-containing protein (B) |

SNF2 N-terminal, Helicase conserved C-terminal, [HAND], SLIDE |

PITG_17273 |

| SSRP1 subunit, FACT complex |

Structure-specific recognition protein, Histone chaperone Rttp106-like |

PITG_14260 |

|

RNA Methylation |

|

|

| FtsJ-like rRNA Methyltransferase (A) |

FtsJ-like methyltransferase |

PITG_09405 |

| FtsJ-like rRNA Methyltransferase (B) |

FtsJ-like methyltransferase |

PITG_06848 |

| FtsJ-like rRNA Methyltransferase (C) |

FtsJ-like methyltransferase |

PITG_16337 |

| Spb1-like rRNA Methyltransferase |

FtsJ-like methyltransferase, DUF3381, Spb1 C-terminal domain |

PITG_00663 |

| Guanosine 2'O tRNA methyltransferase |

CCCH zinc finger, U11-48 K CHHC zinc finger, TRM13 methyltransferase |

PITG_04858 |

| N2,N2-dimethylguanosine tRNA methyltransferase |

N2,N2-dimethylguanosine tRNA methyltransferase (TRM) |

PITG_10166 |

| MnmA-like tRNA 2'-thiouridylase |

tRNA methyltransferase |

PITG_08823 |

|

RNA Silencing |

|

|

| Argonaute (A) |

DUF1785, PAZ, Piwi |

PITG_04470, PITG_04471 |

| Argonaute (B) |

DUF1785, PAZ, Piwi |

PITG_01400, PITG_01443, PITG_01444 |

| Dicer-like |

[DEAD/H box helicase], dsRNA binding, 2x Rnase III domains |

PITG_09292 |

| Drosha-like |

2x Rnase III domains, [dsRNA binding] |

Psojae_300435 |

| dsRNA-binding protein |

dsRNA binding |

PITG_12183 |

| dsRNA-binding protein w/ Bin3 |

[methyltransferase], dsRNA binding, Bicoid-interacting 3 |

PITG_03262 |

| RnaseIII domain protein |

Rnase III domain, [dsRNA binding] |

PITG_08831 |

| RNA-dependant RNA polymerase |

DEAD/H box helicase, Helicase conserved C-terminal, RdRP domain, [NTP transferase] |

PITG_10457 |

|

Transcription factors |

|

|

| Histone-like CBF/NF-Y |

CBF/NF-Y [CENP-S associated centromere protein X] |

PITG_00914 |

| Histone-like CBF/NF-Y w/HMG |

HMG, CBF/NF-Y |

PITG_19530 |

| Med17 subunit of Mediator complex |

Med17 |

PITG_03899 |

| p15 transcriptional coactivator |

2x PC4 |

PITG_07058 |

| TFIIB |

TFIIB zinc-binding, 2x TFIIB |

PITG_14596 |

| TFIID, TATA-binding protein (A) |

2x TBP |

PITG_07312 |

| TFIID, TATA-binding protein (B) |

2x TBP, [DUF3378] |

PITG_12304 |

| TFIID, TATA-binding protein (C) |

TBP, [2x DUF3378], TBP |

PITG_06201 |

| TFIID, TAF1 subunit |

DUF3591, Bromodomain |

PITG_02547 |

| TFIID, TAF2 subunit |

Peptidase M1, [HEAT repeat] |

PITG_18882, PITG_14044 |

| TFIID, TAF5 subunit |

TFIID 90 kDa, 5x WD domain |

PITG_16023 |

| TFIID, TAF6 subunit |

TAF, DUF1546, [HEAT repeat] |

PITG_03978 |

| TFIID, TAF8 subunit |

Bromodomain (histone-like fold), TAF8 C-terminal |

PITG_18355 |

| TFIID, TAF9 subunit |

TFIID 31 kDa |

PITG_04860 |

| TFIID, TAF10 subunit |

TFIID 23–30 kDa |

PITG_07637, PITG_14668 |

| TFIID, TAF12 subunit |

TFIID 20 kDa |

PITG_00683 |

| TFIID, TAF14 subunit |

YEATS |

PITG_01229 |

| TFIIE, alpha subunit |

TFIIEalpha |

PITG_08403 |

| TFIIF, alpha subunit |

TFIIFalpha |

PITG_02327 |

| TFIIF, beta subunit |

TFIIFbeta |

PITG_10081 |

| TFIIH, Rad3 subunit |

DEAD 2, DUF1227, Helicase C-terminal |

PITG_15696 |

| TFIIH, Ssl1 subunit |

Ssl1-like, TFIIH c1-like |

Psojae_345458 |

| TFIIH, Tfb1 subunit |

[TFIIH p62 N-terminal], BSD |

PITG_03523 |

| TFIIH, Tfb2 subunit |

Tfb2 |

PITG_15486 |

| TFIIH, Tfb4 subunit |

Tfb4 |

PITG_00220 |

| TFIIIB, Brf1-like subunit | TFIIB zinc-binding, 2x TFIIB, Brf1-like TBP-binding | PITG_16669 |

aDomains in brackets indicate missing or non-significant matches in some species.

bReference sequences from P. infestans T30-4 (PITG) or P. sojae P6497 v3.0.

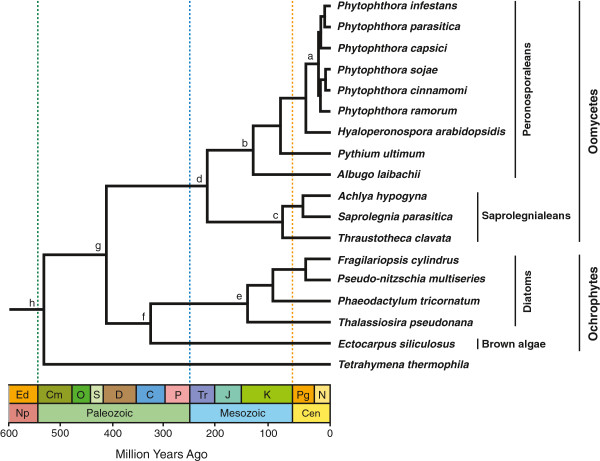

Divergence time analyses

Robust orthology relationships could be determined for 52 out of the initial 70 datasets; 40 of these datasets contained minimal missing data and were used to estimate divergence times (see Additional file 1 for a list of genes included in the analysis). Calibration priors were modeled with a gamma distribution in order to assign higher probabilities to divergence times somewhat older than the hard bound (offset value); initial tests with lognormal priors produced very similar divergence times (data not shown). Five independent analyses of 50 million generations each were run under each of the three models, with the random local clock model being the most computationally intensive. Strict clock and UCLD analyses run on an iMac (10.8.5) desktop with a 2.7 GHz Intel core i5 processor took approximately seven days. Random local clock analyses run on a Linux (Mint14) desktop with a 3.3 GHz Xeon quad core processor took approximately 30 days. Posterior distributions on parameters were identical across all five runs under the strict clock model. Parameter distributions were consistent and overlapping for all five runs under the UCLD model with only one run deviating for the estimate of the root height (700 Ma versus approximately 500 Ma in the other four runs), however all runs showed weak evidence of convergence even after 50 million generations. One run under the random local clock model failed to converge; of the four successful runs, parameter distributions were consistent and overlapping with only one run deviating for the rate estimate (1.76 × 10−3 versus 1.88 × 10−3 for the other three runs). Log and tree files for two of the five runs with the highest effective sample size (ESS) for the likelihood parameter were then combined; under the strict clock model, all five runs performed equally, so the first two runs were combined. Analyses run without data (Prior Only) resulted in time estimates that were markedly different from those obtained with the full dataset for the majority of nodes (Table 3), suggesting that our divergence time estimates were driven by the data themselves and not by settings on the calibration priors. Divergence times among oomycete lineages were consistent among all three models (Table 3), however estimates under the UCLD model may have been influenced by poor mixing as several parameters showed ESS values less than 200 (Tables 3 and 4). The resulting timetree suggests an origin for oomycetes in the mid-Paleozoic, with a divergence between two major lineages, the peronosporaleans and saprolegnialeans, in the early Mesozoic (Figure 1). A complete list of divergence times with 95% confidence intervals for each node under each model is presented in Additional file 2.

Table 3.

Median divergence times (in Ma) for select nodes estimated under the three molecular clock models

| |

Strict clock |

UCLD relaxed clock |

Random local clock |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Node a | Prior only | Full dataset | Prior only | Full dataset | Prior only | Full dataset |

| a |

171.2 |

26.6 |

171.5 |

26.7* |

170.6 |

23.4* |

| b |

271.9 |

139.9 |

271.9 |

119.8* |

271.4 |

134.6 |

| c |

167.5 |

67.0 |

167.0 |

71.6* |

167.1 |

75.1 |

| d |

363.6 |

197.2 |

363.7 |

191.0* |

363.1 |

214.1 |

| e |

83.1 |

180.1 |

83.0 |

97.5* |

83.0 |

139.4 |

| f |

183.8 |

364.4 |

183.7 |

191.0 |

183.8 |

334.1 |

| g |

447.4 |

414.7 |

447.4 |

424.8 |

447.6 |

415.6 |

| h | 526.6 | 545.3 | 527.04 | 475.0* | 527.1 | 533.9 |

Table 4.

Mean posterior values for select parameters estimated under the three molecular clock models

| |

Strict clock |

UCLD relaxed clock |

Random local clock |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parameter | Prior only | Full dataset | Prior only | Full dataset | Prior only | Full dataset |

| Likelihood |

n/a |

−359159.81 |

n/a |

−358847.49 |

n/a |

−358852.83 |

| Posterior |

n/a |

−359328.94 |

n/a |

−358975.87 |

n/a |

−359061.08 |

| Yule.birthrate |

0.0052 |

0.0062 |

0.0052 |

0.0074 |

0.0052 |

0.0065 |

| Clock.rate |

0.9990 |

0.0018 |

n/a |

n/a |

0.9970 |

0.0019 |

| ucld.mean |

n/a |

n/a |

0.1000 |

0.0024* |

n/a |

n/a |

| ucld.stdev |

n/a |

n/a |

0.0999 |

0.5550* |

n/a |

n/a |

| CoefficientOfVariation |

n/a |

n/a |

0.0979 |

0.5370* |

0.1230 |

0.2380* |

| RateChangeCount | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | 0.6950 | 8.7050 |

Asterisks (*) indicate ESS < 200. n/a – not applicable.

Figure 1.

Timetree of oomycete evolution. Divergence times shown were estimated under the random local clock model. Vertical dashed lines indicate boundaries between geologic eras.

Discussion

Models for estimating divergence times under a molecular clock have become more complex over the past two decades. In this study we have used three distinct models, a single-rate strict clock, a UCLD relaxed clock, and a random local clock, to estimate divergence times among the fungal-like oomycetes. Analyses run under the strict clock model performed robustly, with all parameters showing evidence of thorough sampling (ESS > > 1000) and chain convergence. Because we had no a priori expectation of rate homogeneity among oomycetes or between oomycetes and ochrophytes, we also estimated divergence times under “relaxed” clock models. Both the UCLD and random local clock models indicated moderate to high levels of rate variation among lineages (as shown by the coefficient of variation parameter, Table 4), suggesting that a strict clock model was not appropriate for our dataset regardless of performance of the MCMC. In addition, an analysis of Bayes factors suggested that the two relaxed clock methods were a better fit for the data (ln Bayes factor in favor of relaxed clock models over strict clock >100). Rates estimated under the UCLD model appeared to be strongly influenced by the calibration priors, leading to rates 1.5 to 3.5 times higher in the ochrophyte lineages than in the oomycetes (data not shown). However, UCLD analyses failed to converge even after 50 million generations, thus limiting our ability to interpret parameter and divergence time estimates. Only a few parameters showed signs of poor mixing in the random local clock analyses (ESS < 200), but in general there was good evidence of chain convergence under this model, with the trade-off of long computational times.

Despite differences in performance among the three clock models, divergence time estimates among oomycetes were strikingly consistent (Table 3 and Additional file 2), and all models estimated a mid-Paleozoic origin for oomycetes (Figure 1). Our estimate for the divergence of oomycetes from other stramenopiles is somewhat consistent with results from a study of ochrophyte evolution using small subunit ribosomal DNA data [34], but is considerably younger than estimates generated from broader studies of eukaryote evolution [31,32]. However, it seems likely that the times recovered here for the divergence between oomycetes and ochrophytes, as well as the root node, may be underestimated, for several reasons. A recent simulation study of relaxed clock models showed that the deepest nodes in a tree tend to be underestimated when shallow calibrations are used [48], which reflects our reliance on diatom calibrations to estimate divergences throughout the tree. Also, the posterior distributions recovered for the ingroup (node g in Figure 1) and root (node h) time estimates overlapped with their respective prior distributions, and were tightly constrained by the lower limit of 408 Ma imposed by the priors (data not shown). In addition, the long branch connecting the origin of oomycetes (node g) to the divergence between the peronosporaleans and saprolegnialeans (node d), as well as the long branch in the calibration taxa (between nodes e and f), may have influenced rate estimates under the UCLD and random local clock models. As a result, divergence times estimated for these nodes were sensitive to the model, particularly the ochrophyte estimates under the UCLD clock (Table 3 and Additional file 2); however, given the poor performance of the UCLD analysis, it is difficult to assess the reliability of these estimates. Additional sequence data from basal oomycetes such as Eurychasma dicksonii[49] and Haliphthoros sp. [50], as well as from more ochrophyte calibration taxa, will help break up these long branches and led to more reliable rate estimates. The oldest accepted oomycete fossils come from the Lower Devonian Rhynie Chert, which is thought to have been a non-marine hot spring environment [21,22]. Phylogenetic evidence suggests that the earliest diverging oomycetes were likely marine [15,20], therefore the origin of this group may have occurred some time prior to the appearance of fossils in non-marine environments.

Fossil evidence of oomycetes also occurs throughout the Carboniferous, particularly in association with lycophytes (reviewed in [21]). While previous authors have suggested affinities with certain taxonomic groups (e.g., [25,26]), the divergence times estimated here indicate that modern peronosporalean and saprolegnialean lineages originated much later, in the mid to late Mesozoic (Figure 1). Modern saprolegnialeans, such as Saprolegnia parasitica, are commonly associated with freshwater environments, and can be devastating pathogens of fish, amphibians, crustaceans, and insects [45]; saprotrophic species, such as Thraustotheca clavata, are also known from this group. In contrast, modern peronosporaleans are predominately terrestrial and many are significant plant pathogens. Two species included in our analysis, Hyaloperonospora arabidopsidis[39] and Albugo laibachii[37], are obligate biotrophs who are fully dependent on their host (Arabidopsis). Phytophthora species cause disease on a wide variety of plants, and significant effort has been undertaken to understand their mechanisms of virulence and host specificity (reviewed in [51]). While it is undesirable to extrapolate as to the likely hosts for early diverging lineages, it does seem reasonable to suggest that host availability was not a constraining factor in oomycete diversification. Particularly for the modern plant pathogenic oomycetes, both fossil and molecular clock evidence suggests that the major lineages of angiosperms had diversified by the mid-Cretaceous [52], prior to our estimates for divergences among the peronosporaleans. The evolution of pathogenic lifestyles, therefore, may have been in response to certain environmental changes, or may have been facilitated by the horizontal transfer of pathogenicity-related genes from true Fungi [53-55] or from bacteria [45,56], as has been suggested previously.

In this study, we chose to focus on conserved regulators of eukaryotic gene expression to examine their presence and level of conservation in pathogenic oomycetes. Mechanisms of gene expression regulation are highly conserved across eukaryotes and were most likely present in the last common ancestor, including epigenetic and RNA-based processes for transcriptional and post-transcriptional gene silencing [57-59]. Although we have not conducted an exhaustive survey here, our results suggest that the common ancestor of oomycetes possessed a full complement of regulatory proteins, including those involved in histone modification, RNA interference, and tRNA and rRNA methylation. Surprisingly, no orthologs of canonical DNA methyltransferases could be identified in the genomes of oomycetes. A single putative DNA methylase is present in the genome of Pythium ultimum (T014901), but no orthologs could be detected in the other oomycete genomes. Gene silencing studies in Phytophthora infestans have failed to detect evidence of cytosine methylation [60,61], however recent work in P. sojae does suggest the presence of methylated DNA [62]. DNA methyltransferases also appear to be absent from the Ectocarpus genome [38], as well as from the model eukaryotes Saccharomyces cerevisiae and Caenorhabditis elegans[63], however several are known from diatoms [64,65]. Further study is therefore needed to confirm the presence and mechanism of DNA methylation in oomycetes.

Conclusions

This is the first study to estimate divergence times among the fungal-like oomycetes. The consistency of our time estimates under three distinct molecular clock models suggests that the resulting timetree likely recovers the main divergences among lineages, which occurred in the mid to late Mesozoic. Our estimates for the origin of oomycetes and the divergence of stramenopiles from other eukaryotes may have been underestimated due to the limited fossil information available for the taxa included in this study. Additional information from the oomycete fossil record, especially from the diverse Cretaceous assemblages, as well as new sequence data from basal oomycete lineages and other under-sampled eukaryotes [66], may help future molecular clock studies better estimate evolutionary rates.

Methods

Data mining

Reference sequences for canonical eukaryotic transcription factors and proteins involved in post-transcriptional gene silencing, DNA and RNA methylation, and chromatin modification were obtained from the Gene Database at NCBI (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/gene) for human, Drosophila, Saccharomyces, and/or Arabidopsis. The reference protein sequences were then used to search for homologs in the genome of Phytophthora infestans T30-4 [42]. Additional reference sequences were also obtained from a study of gene silencing in P. infestans[36]. Both the eukaryotic reference sequences and the putative P. infestans homologs were used to search the available genomes of oomycetes, diatoms, and a brown alga (Table 1); outgroup sequences were obtained from Tetrahymena thermophila when available. All potential homologs of equivalent BLAST e-values within each genome were included for orthology assessment.

Dataset assembly

Protein domains were determined for all potential homologs using Pfam [67]. Sequences that did not contain the appropriate domains for proper protein function were removed from each dataset except in cases where the protein sequence appeared truncated due to genome misannotation, particularly for Hyaloperonospora arabidopsidis. Each dataset was aligned under default settings in ClustalX v2 [68], and preliminary neighbor-joining phylogenies were generated under a Poisson correction with pairwise deletion of alignment gaps in MEGA v5 [69]. Sequences within each dataset were considered orthologous if they shared protein domains and their phylogeny reflected known species relationships. In datasets with species-specific paralogs, one sequence was arbitrarily chosen to represent the ortholog for divergence time estimation. In cases where orthology was ambiguous or no homolog could be identified, the sequence was coded as missing data. A complete list of protein accession numbers per gene for each genome is available in Additional file 1.

Divergence time analysis

Protein datasets with robust orthology were used to co-estimate phylogeny and divergence times using Bayesian inference in BEAST v1.7.5 [70]. Initial runs of 10 million generations were used under each clock model to evaluate settings on priors and to generate a user tree for subsequent analyses. For the final analyses, each protein dataset was treated as a separate partition under a WAG substitution model; a Yule speciation process was assumed with a uniform distribution on the birthrate (0–100; initial value 0.01). For the strict clock analyses, the rate parameter (clock.rate) was modeled with an exponential prior distribution (mean 1.0, initial value 0.01). For the UCLD relaxed clock model, an exponential prior distribution (mean 0.1, initial value 0.01) was used for the mean rate (ucld.mean) and standard deviation (ucld.stdev). Several parameters control the rate and number of rate changes under the random local clock model; a Poisson distribution (mean 0.693) was used as the prior for the number of local clocks (rateChanges), an exponential prior distribution (mean 1.0, initial value 0.001) was used for the relative rates among local clocks (localclocks.relativerates), and an exponential prior distribution (mean 1.0, initital value 0.01) was used for the rate (clock.rate). Five independent analyses were run for 50 million generations each, under all three clock models; log and tree files from the two runs with the highest parameter ESS values per model were combined (after removing burn-in from each run) using LogCombiner v1.7.5. Tracer v1.5 [71] was used to evaluate convergence, estimate the appropriate burn-in for each run, and calculate Bayes factors for model comparisons. Analyses were also repeated without data (priors only) to determine the impact of calibration settings on the resulting divergence time estimates; three independent runs of 50 million generations each were performed under each clock model. Trees were visualized in FigTree v1.4 [72].

Fossil evidence from diatoms and oomycetes was used to calibrate the molecular clock analyses; all calibrations were modeled with a gamma prior distribution (shape 2.0) with the offset value set as the uppermost boundary of the time interval (stage) containing the relevant fossil. The value for the scale parameter was set so that the age at the 95% quantile was roughly equivalent to the lowermost boundary on the geologic epoch containing the relevant fossil. Appropriate geological times were obtained from the International Commission on Stratigraphy chronostratigraphic chart, January 2013 version (http://stratigraphy.org). Fossil evidence from the Late Cretaceous (Campanian) pennate diatoms [73] provided a minimum age of 72.1 Ma on the divergence between Thalassiosira and Phaeodactylum (5-95% quantiles = 74–100 Ma). Early Jurassic (Toarcian) diatom fossils [74] provided a minimum age of 174 Ma on the divergence between diatoms and Ectocarpus (5-95% quantiles = 176–202 Ma). The Rhynie chert oomycete fossils [21] were used to define a minimum divergence time of 408 Ma between oomycetes and ochrophytes (5-95% quantiles = 418–550 Ma). A wide uniform prior distribution (408–1750 Ma; initial value 635 Ma) was used for the root age as there are few robust estimates on the divergence between alveolates and stramenopiles. Beast XML-formatted data files have been deposited in Dryad [75].

Availability of supporting data

The data sets supporting the results of this article are available in the Dryad Digital Repository, http://dx.doi.org/10.5061/dryad.39mc5.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

JEB and NHM designed the experiment and performed the data mining. JEB performed the divergence time analyses and drafted the manuscript. Both authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Supplementary Material

Genome accession numbers for all proteins included in this study.

Timetree, divergence times, and 95% confidence intervals per node estimated under the three clock models.

Contributor Information

Nahill H Matari, Email: nahill.matari@gmail.com.

Jaime E Blair, Email: jaime.blair@fandm.edu.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Dr. Chris Lane (University of Rhode Island) for access to unpublished genomic data from Achlya hypogyna and Thraustotheca clavata, and Dr. Vipaporn Phuntumart (Bowling Green State University) for discussion of unpublished methylation data from Phytophthora sojae. We also thank Jason Brooks and Anthony Weaver for assistance with the random local clock analyses, and Dr. Jorge Mena-Ali (F&M) for helpful conversations regarding parameter settings. This work was supported by the US Department of Agriculture National Institute of Food and Agriculture (2011-68004-30104 and 2010-65110-20488 to J.E.B) and by a grant to Franklin & Marshall College from the Howard Hughes Medical Institute Science Education Program.

References

- Knoll AH. In: Fundamentals of Geobiology. Knoll AH, Canfield DE, Konhauser KO, editor. Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell; 2012. The fossil record of microbial life. [Google Scholar]

- Zuckerkandl E, Pauling L. In: Horizons in Biochemistry. Kasha M, Pullman B, editor. New York: Academic Press; 1962. Molecular disease, evolution, and genic heterogeneity; pp. 189–225. [Google Scholar]

- Zuckerkandl E, Pauling L. In: Evolving Genes and Proteins. Bryson V, Vogel HJ, editor. New York: Academic Press; 1965. Evolutionary divergence and convergence in proteins; pp. 97–166. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar S. Molecular clocks: four decades of evolution. Nat Rev Genet. 2005;6(8):654–662. doi: 10.1038/nrg1659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanderson MJ. A nonparametric approach to estimating divergence times in the absence of rate constancy. Mol Biol Evol. 1997;14(12):1218–1231. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a025731. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sanderson MJ. Estimating absolute rates of molecular evolution and divergence times: a penalized likelihood approach. Mol Biol Evol. 2002;19(1):101–109. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a003974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thorne JL, Kishino H, Painter IS. Estimating the rate of evolution of the rate of molecular evolution. Mol Biol Evol. 1998;15(12):1647–1657. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a025892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aris-Brosou S, Yang Z. Effects of models of rate evolution on estimation of divergence dates with special reference to the metazoan 18S ribosomal RNA phylogeny. Syst Biol. 2002;51(5):703–714. doi: 10.1080/10635150290102375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drummond AJ, Ho SYW, Phillips MJ, Rambaut A. Relaxed phylogenetics and dating with confidence. PLoS Biol. 2006;4(5):e88. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0040088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drummond AJ, Suchard MA. Bayesian random local clocks, or one rate to rule them all. BMC Biol. 2010;8:114. doi: 10.1186/1741-7007-8-114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ho SYW, Phillips MJ. Accounting for calibration uncertainty in phylogenetic estimation of evolutionary divergence times. Syst Biol. 2009;58(3):367–380. doi: 10.1093/sysbio/syp035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parham JF, Donoghue PCJ, Bell CJ, Calway TD, Head JJ, Holroyd PA, Inoue JG, Irmis RB, Joyce WG, Ksepka DT, Patané JSL, Smith ND, Tarver JE, van Tuinen M, Yang Z, Angielczyk KD, Greenwood JM, Hipsley CA, Jacobs L, Makovicky PJ, Müller J, Smith KT, Theodor JM, Warnock RCM, Benton MJ. Best practices for justifying fossil calibrations. Syst Biol. 2012;61(2):346–359. doi: 10.1093/sysbio/syr107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warnock RCM, Yang Z, Donoghue PCJ. Exploring uncertainty in the calibration of the molecular clock. Biol Lett. 2012;8(1):156–159. doi: 10.1098/rsbl.2011.0710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dick MW. Straminipilous Fungi. Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic Publishers; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Beakes GW, Glocklin SL, Sekimoto S. The evolutionary phylogeny of the oomycete "fungi". Protoplasma. 2012;249(1):3–19. doi: 10.1007/s00709-011-0269-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cavalier-Smith T. Principles of protein and lipid targeting in secondary symbiogenesis: Euglenoid, Dinoflagellate, and Sporozoan plastid origins and the eukaryote family tree. J Eukaryot Microbiol. 1999;46(4):347–366. doi: 10.1111/j.1550-7408.1999.tb04614.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burki F, Shalchian-Tabrizi K, Minge M, Skjæveland Å, Nikolaev SI, Jakobsen KS, Pawlowski J. Phylogenomics reshuffles the eukaryotic supergroups. PLoS ONE. 2007;2(8):e790. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0000790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adl SM, Simpson AGB, Lane CE, Lukeš J, Bass D, Bowser SS, Brown MW, Burki F, Dunthorn M, Hampl V, Heiss A, Hoppenrath M, Lara E, le Gall L, Lynn DH, McManus H, Mitchell EAD, Mozley-Stanridge SE, Parfrey LW, Pawlowski J, Rueckert S, Shadwick L, Schoch CL, Smirnov A, Spiegel FW. The Revised Classification of Eukaryotes. J Eukaryot Microbiol. 2012;59(5):429–514. doi: 10.1111/j.1550-7408.2012.00644.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fry W. Phytophthora infestans: the plant (and R gene) destroyer. Mol Plant Pathol. 2008;9(3):385–402. doi: 10.1111/j.1364-3703.2007.00465.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beakes GW, Sekimoto S. In: Oomycete Genetics and Genomics: Diversity, Interactions, and Research Tools. Lamour K, Kamoun S, editor. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, Inc; 2009. The evolutionary phylogeny of oomycetes - insights gained from studies of holocarpic parasites of algae and invertebrates; pp. 1–24. [Google Scholar]

- Krings M, Taylor TN, Dotzler N. The fossil record of the Peronosporomycetes (Oomycota) Mycologia. 2011;103(3):445–457. doi: 10.3852/10-278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor TN, Krings M, Kerp H. Hassiella monospora gen. et sp. nov., a microfungus from the 400 million year old Rhynie chert. Mycol Res. 2006;110(6):628–632. doi: 10.1016/j.mycres.2006.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krings M, Taylor TN, Taylor EL, Kerp H, Hass H, Dotzler N, Harper CJ. Microfossils from the Lower Devonian Rhynie Chert with Suggested Affinities to the Peronosporomycetes. J Paleontol. 2012;86(2):358–367. doi: 10.1666/11-087.1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Krings M, Taylor TN, Dotzler N, Decombeix A-L. Galtierella biscalithecae nov. gen. et sp., a Late Pennsylvanian endophytic water mold (Peronosporomycetes) from France. Comptes Rendus Palevol. 2010;9(1–2):5–11. [Google Scholar]

- Strullu-Derrien C, Kenrick P, Rioult JP, Strullu DG. Evidence of parasitic Oomycetes (Peronosporomycetes) infecting the stem cortex of the Carboniferous seed fern Lyginopteris oldhamia. Proc R Soc B Biol Sci. 2011;278(1706):675–680. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2010.1603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stidd BM, Cosentino K. Albugo-like oogonia from the American Carboniferous. Science. 1975;190(4219):1092–1093. doi: 10.1126/science.190.4219.1092. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dotzler N, Krings M, Agerer R, Galtier J, Taylor TN. Combresomyces cornifer gen. sp. nov., an endophytic peronosporomycete in Lepidodendron from the Carboniferous of central France. Mycol Res. 2008;112(9):1107–1114. doi: 10.1016/j.mycres.2008.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwendemann AB, Taylor TN, Taylor EL, Krings M, Dotzler N. Combresomyces cornifer from the Triassic of Antarctica: Evolutionary stasis in the Peronosporomycetes. Rev Palaeobot Palynol. 2009;154(1–4):1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Krings M, Taylor TN, Dotzler N. In: Biocomplexity of Plant-Fungal Interactions. Southworth D, editor. Ames, Iowa: John Wiley & Sons, Inc; 2012. Fungal endophytes as a driving force in lan plant evolution: evidence from the fossil record. [Google Scholar]

- Berney C, Pawlowski J. A molecular time-scale for eukaryote evolution recalibrated with the continuous microfossil record. Proc R Soc B Biol Sci. 2006;273(1596):1867–1872. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2006.3537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parfrey LW, Lahr DJG, Knoll AH, Katz LA. Estimating the timing of early eukaryotic diversification with multigene molecular clocks. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2011;108(33):13624–13629. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1110633108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hackett JD, Yoon HS, Butterfield NJ, Sanderson MJ, Bhattacharya D, Falkowski PG, Knoll AH. Evolution of Primary Producers in the Sea. Burlington, MA: Elsevier Academic Press; 2007. Plastid endosymbiosis: sources and timing of the major events; pp. 109–132. [Google Scholar]

- Phillips N, Calhoun S, Moustafa A, Bhattacharya D, Braun EL. Genomic insights into evolutionary relationships among heterokont lineages emphasizing the Phaeophyceae. J Phycol. 2008;44(1):15–18. doi: 10.1111/j.1529-8817.2007.00435.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown JW, Sorhannus U. A molecular genetic timescale for the diversification of autotrophic stramenopiles (Ochrophyta): substantive underestimation of putative fossil ages. PLoS ONE. 2010;5(9):e12759. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0012759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siomi H, Siomi MC. On the road to reading the RNA-interference code. Nature. 2009;457(7228):396–404. doi: 10.1038/nature07754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vetukuri RR, Avrova AO, Grenville-Briggs LJ, Van West P, Soderbom F, Savenkov EI, Whisson SC, Dixelius C. Evidence for involvement of Dicer-like, Argonaute and histone deacetylase proteins in gene silencing in Phytophthora infestans. Mol Plant Pathol. 2011;12(8):772–785. doi: 10.1111/j.1364-3703.2011.00710.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kemen E, Gardiner A, Schultz-Larsen T, Kemen AC, Balmuth AL, Robert-Seilaniantz A, Bailey K, Holub E, Studholme DJ, MacLean D, Jones JDG. Gene gain and loss during evolution of obligate parasitism in the white rust pathogen of Arabidopsis thaliana. PLoS Biol. 2011;9(7):e1001094. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1001094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cock JM, Sterck L, Rouze P, Scornet D, Allen AE, Amoutzias G, Anthouard V, Artiguenave F, Aury J-M, Badger JH, Beszteri B, Billiau K, Bonnet E, Bothwell JH, Bowler C, Boyen C, Brownlee C, Carrano CJ, Charrier B, Cho GY, Coelho SM, Collen J, Corre E, Da Silva C, Delage L, Delaroque N, Dittami SM, Doulbeau S, Elias M, Farnham G. et al. The Ectocarpus genome and the independent evolution of multicellularity in brown algae. Nature. 2010;465(7298):617–621. doi: 10.1038/nature09016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baxter L, Tripathy S, Ishaque N, Boot N, Cabral A, Kemen E, Thines M, Ah-Fong A, Anderson R, Badejoko W, Bittner-Eddy P, Boore JL, Chibucos MC, Coates M, Dehal P, Delehaunty K, Dong S, Downton P, Dumas B, Fabro G, Fronick C, Fuerstenberg SI, Fulton L, Gaulin E, Govers F, Hughes L, Humphray S, Jiang RHY, Judelson H, Kamoun S. Signatures of adaptation to obligate biotrophy in the Hyaloperonospora arabidopsidis genome. Science. 2010;330(6010):1549–1551. doi: 10.1126/science.1195203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowler C, Allen AE, Badger JH, Grimwood J, Jabbari K, Kuo A, Maheswari U, Martens C, Maumus F, Otillar RP, Rayko E, Salamov A, Vandepoele K, Beszteri B, Gruber A, Heijde M, Katinka M, Mock T, Valentin K, Verret F, Berges JA, Brownlee C, Cadoret J-P, Chiovitti A, Choi CJ, Coesel S, De Martino A, Detter JC, Durkin C, Falciatore A. et al. The Phaeodactylum genome reveals the evolutionary history of diatom genomes. Nature. 2008;456(7219):239–244. doi: 10.1038/nature07410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamour KH, Mudge J, Gobena D, Hurtado-Gonzales OP, Schmutz J, Kuo A, Miller NA, Rice BJ, Raffaele S, Cano LM, Bharti AK, Donahoo RS, Finley S, Huitema E, Hulvey J, Platt D, Salamov A, Savidor A, Sharma R, Stam R, Storey D, Thines M, Win J, Haas BJ, Dinwiddie DL, Jenkins J, Knight JR, Affourtit JP, Han CS, Chertkov O. Genome sequencing and mapping reveal loss of heterozygosity as a mechanism for rapid adaptation in the vegetable pathogen Phytophthora capsici. Mol Plant Microbe Interact. 2012;25(10):1350–1360. doi: 10.1094/MPMI-02-12-0028-R. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haas BJ, Kamoun S, Zody MC, Jiang RHY, Handsaker RE, Cano LM, Grabherr M, Kodira CD, Raffaele S, Torto-Alalibo T, Bozkurt TO, Ah-Fong AMV, Alvarado L, Anderson VL, Armstrong MR, Avrova A, Baxter L, Beynon J, Boevink PC, Bollmann SR, Bos JIB, Bulone V, Cai G, Cakir C, Carrington JC, Chawner M, Conti L, Costanzo S, Ewan R, Fahlgren N. et al. Genome sequence and analysis of the Irish potato famine pathogen Phytophthora infestans. Nature. 2009;461(7262):393–398. doi: 10.1038/nature08358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tyler BM, Tripathy S, Zhang X, Dehal P, Jiang RHY, Aerts A, Arredondo FD, Baxter L, Bensasson D, Beynon JL, Tyler BM, Tripathy S, Zhang X, Dehal P, Jiang RHY, Aerts A, Arredondo FD, Baxter L, Bensasson D, Beynon JL, Chapman J, Damasceno CMB, Dorrance AE, Dou D, Dickerman AW, Dubchak IL, Garbelotto M, Gijzen M, Gordon SG, Govers F. et al. Phytophthora genome sequences uncover evolutionary origins and mechanisms of pathogenesis. Science. 2006;313(5791):1261–1266. doi: 10.1126/science.1128796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levesque CA, Brouwer H, Cano L, Hamilton J, Holt C, Huitema E, Raffaele S, Robideau G, Thines M, Win J, Levesque CA, Brouwer H, Cano L, Hamilton J, Holt C, Huitema E, Raffaele S, Robideau G, Thines M, Win J, Zerillo M, Beakes G, Boore J, Busam D, Dumas B, Ferriera S, Fuerstenberg S, Gachon C, Gaulin E, Govers F. et al. Genome sequence of the necrotrophic plant pathogen Pythium ultimum reveals original pathogenicity mechanisms and effector repertoire. Genome Biol. 2010;11(7):R73. doi: 10.1186/gb-2010-11-7-r73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang RHY, de Bruijn I, Haas BJ, Belmonte R, Löbach L, Christie J, van den Ackerveken G, Bottin A, Bulone V, Díaz-Moreno SM, Dumas B, Fan L, Gaulin E, Govers F, Grenville-Briggs LJ, Horner NR, Levin JZ, Mammella M, Meijer HJG, Morris P, Nusbaum C, Oome S, Phillips AJ, van Rooyen D, Rzeszutek E, Saraiva M, Secombes CJ, Seidl MF, Snel B, Stassen JHM. et al. Distinctive expansion of potential virulence genes in the genome of the oomycete fish pathogen Saprolegnia parasitica. PLoS Genet. 2013;9(6):e1003272. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1003272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stover NA, Krieger CJ, Binkley G, Dong Q, Fisk DG, Nash R, Sethuraman A, Weng S, Cherry JM. Tetrahymena Genome Database (TGD): a new genomic resource for Tetrahymena thermophila research. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34(S1):D500–D503. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkj054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armbrust EV, Berges JA, Bowler C, Green BR, Martinez D, Putnam NH, Zhou S, Allen AE, Apt KE, Bechner M, Brzezinski MA, Chaal BK, Chiovitti A, Davis AK, Demarest MS, Detter JC, Glavina T, Goodstein D, Hadi MZ, Hellsten U, Hildebrand M, Jenkins BD, Jurka J, Kapitonov VV, Kröger N, Lau WWY, Lane TW, Larimer FW, Lippmeier JC, Lucas S. et al. The genome of the diatom Thalassiosira pseudonana: ecology, evolution, and metabolism. Science. 2004;306(5693):79–86. doi: 10.1126/science.1101156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Battistuzzi FU, Filipski A, Hedges SB, Kumar S. Performance of relaxed-clock methods in estimating evolutionary divergence times and their credibility intervals. Mol Biol Evol. 2010;27(6):1289–1300. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msq014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grenville-Briggs L, Gachon CMM, Strittmatter M, Sterck L, Küpper FC, van West P. A Molecular Insight into Algal-Oomycete Warfare: cDNA Analysis of Ectocarpus siliculosus Infected with the Basal Oomycete Eurychasma dicksonii. PLoS ONE. 2011;6(9):e24500. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0024500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sekimoto S, Hatai K, Honda D. Molecular phylogeny of an unidentified Haliphthoros-like marine oomycete and Haliphthoros milfordensis inferred from nuclear-encoded small- and large-subunit rRNA genes and mitochondrial-encoded cox2 gene. Mycoscience. 2007;48(4):212–221. doi: 10.1007/S10267-007-0357-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang RHY, Tyler BM. Mechanisms and evolution of virulence in oomycetes. Annu Rev Phytopathol. 2012;50(1):295–318. doi: 10.1146/annurev-phyto-081211-172912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bell CD, Soltis DE, Soltis PS. The age and diversification of the angiosperms re-revisited. Am J Bot. 2010;97(8):1296–1303. doi: 10.3732/ajb.0900346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luis P, Gauthier A, Trouvelot S, Poinssot B, Frettinger P. Identification of Plasmopara viticola genes potentially involved in pathogenesis on grapevine suggests new similarities between oomycetes and true Fungi. Phytopathology. 2013;103(10):1035–1044. doi: 10.1094/PHYTO-06-12-0121-R. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris PF, Schlosser LR, Onasch KD, Wittenschlaeger T, Austin R, Provart N. Multiple horizontal gene transfer events and domain fusions have created novel regulatory and metabolic networks in the oomycete genome. PLoS ONE. 2009;4(7):e6133. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0006133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richards TA, Soanes DM, Jones MDM, Vasieva O, Leonard G, Paszkiewicz K, Foster PG, Hall N, Talbot NJ. Horizontal gene transfer facilitated the evolution of plant parasitic mechanisms in the oomycetes. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2011;108(37):15258–15263. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1105100108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belbahri L, Calmin G, Mauch F, Andersson JO. Evolution of the cutinase gene family: evidence for lateral gene transfer of a candidate Phytophthora virulence factor. Gene. 2008;408(1–2):1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2007.10.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins L, Chen XS. Ancestral RNA: The RNA biology of the eukaryotic ancestor. RNA Biol. 2009;6(5):495–502. doi: 10.4161/rna.6.5.9551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katz LA. Origin and diversification of eukaryotes. Annu Rev Microbiol. 2012;66(1):411–427. doi: 10.1146/annurev-micro-090110-102808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shabalina SA, Koonin EV. Origins and evolution of eukaryotic RNA interference. Trends Ecol Evol. 2008;23(10):578–587. doi: 10.1016/j.tree.2008.06.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van West P, Kamoun S, van’t Klooster JW, Govers F. Internuclear gene silencing in Phytophthora infestans. Mol Cell. 1999;3(3):339–348. doi: 10.1016/S1097-2765(00)80461-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van West P, Shepherd SJ, Walker CA, Li S, Appiah AA, Grenville-Briggs LJ, Govers F, Gow NAR. Internuclear gene silencing in Phytophthora infestans is established through chromatin remodelling. Microbiology. 2008;154(5):1482–1490. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.2007/015545-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spangler M. MS thesis. Biological Sciences Department: Bowling Green State Universit; 2012. Cytosine methylation of Phytophthora sojae by methylated DNA immunoprecipitation. [Google Scholar]

- Goll MG, Bestor TH. Eukaryotic cytosine methyltransferases. Annu Rev Biochem. 2005;74(1):481–514. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.74.010904.153721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Riso V, Raniello R, Maumus F, Rogato A, Bowler C, Falciatore A. Gene silencing in the marine diatom Phaeodactylum tricornutum. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37(14):e96. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montsant A, Allen AE, Coesel S, Martino AD, Falciatore A, Mangogna M, Siaut M, Heijde M, Jabbari K, Maheswari U, Rayko E, Vardi A, Apt KE, Berges JA, Chiovitti A, Davis AK, Thamatrakoln K, Hadi MZ, Lane TW, Lippmeier JC, Martinez D, Parker MS, Pazour GJ, Saito MA, Rokhsar DS, Armbrust EV, Bowler C. Identification and comparative genomic analysis of signaling and regulatory components in the diatom Thalassiosira pseudonana. J Phycol. 2007;43(3):585–604. doi: 10.1111/j.1529-8817.2007.00342.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- del Campo J, Sieracki ME, Molestina R, Keeling P, Massana R, Ruiz-Trillo I. The others: our biased perspectives of eukaryotic genomes. Trends Ecol Evol. 2014;29(5):252–259. doi: 10.1016/j.tree.2014.03.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Punta M, Coggill PC, Eberhardt RY, Mistry J, Tate J, Boursnell C, Pang N, Forslund K, Ceric G, Clements J, Heger A, Holm L, Sonnhammer ELL, Eddy SR, Bateman A, Finn RD. The Pfam protein families database. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40(D1):D290–D301. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr1065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larkin MA, Blackshields G, Brown NP, Chenna R, McGettigan PA, McWilliam H, Valentin F, Wallace IM, Wilm A, Lopez R, Thompson JD, Gibson TJ, Higgins DG. Clustal W and Clustal X version 2.0. Bioinformatics. 2007;23(21):2947–2948. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btm404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamura K, Peterson D, Peterson N, Stecher G, Nei M, Kumar S. MEGA5: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis using Maximum Likelihood, Evolutionary Distance, and Maximum Parsimony methods. Mol Biol Evol. 2011;28(10):2731–2739. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msr121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drummond AJ, Suchard MA, Xie D, Rambaut A. Bayesian Phylogenetics with BEAUti and the BEAST 1.7. Mol Biol Evol. 2012;29(8):1969–1973. doi: 10.1093/molbev/mss075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rambaut A, Drummond AJ. Tracer version 1.5, available at. http://tree.bio.ed.ac.uk/software/tracer/

- Rambaut A, Drummond AJ. FigTree version 1.4, available at. http://tree.bio.ed.ac.uk/software/figtree.

- Kooistra W, Gersonde R, Medlin LK, Mann DG. In: Evolution of Primary Producers in the Sea. Falkowski PG, Knoll AH, editor. Burlington, MA: Elsevier Academic Press; 2007. The origin and evolution of the Diatoms: their adaptation to a planktonic existence; pp. 207–249. [Google Scholar]

- Sims PA, Mann DG, Medlin LK. Evolution of the diatoms: insights from fossil, biological and molecular data. Phycologia. 2006;45(4):361–402. doi: 10.2216/05-22.1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Matari N, Blair JE. Data from: a multilocus timescale for oomycete evolution estimated under three distinct molecular clock models. Dryad Digital Repository. 2014. http://dx.doi.org/10.5061/dryad.39mc5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Genome accession numbers for all proteins included in this study.

Timetree, divergence times, and 95% confidence intervals per node estimated under the three clock models.