Abstract

This editorial provides insights into how informatics can attract highly trained students by involving them in science, technology, engineering, and math (STEM) training at the high school level and continuing to provide mentorship and research opportunities through the formative years of their education. Our central premise is that the trajectory necessary to be expert in the emergent fields in front of them requires acceleration at an early time point. Both pathology (and biomedical) informatics are new disciplines which would benefit from involvement by students at an early stage of their education. In 2009, Michael T Lotze MD, Kirsten Livesey (then a medical student, now a medical resident at University of Pittsburgh Medical Center (UPMC)), Richard Hersheberger, PhD (Currently, Dean at Roswell Park), and Megan Seippel, MS (the administrator) launched the University of Pittsburgh Cancer Institute (UPCI) Summer Academy to bring high school students for an 8 week summer academy focused on Cancer Biology. Initially, pathology and biomedical informatics were involved only in the classroom component of the UPCI Summer Academy. In 2011, due to popular interest, an informatics track called Computer Science, Biology and Biomedical Informatics (CoSBBI) was launched. CoSBBI currently acts as a feeder program for the undergraduate degree program in bioinformatics at the University of Pittsburgh, which is a joint degree offered by the Departments of Biology and Computer Science. We believe training in bioinformatics is the best foundation for students interested in future careers in pathology informatics or biomedical informatics. We describe our approach to the recruitment, training and research mentoring of high school students to create a pipeline of exceptionally well-trained applicants for both the disciplines of pathology informatics and biomedical informatics. We emphasize here how mentoring of high school students in pathology informatics and biomedical informatics will be critical to assuring their success as leaders in the era of big data and personalized medicine.

Keywords: Bioinformatics, education, medical informatics, science, technology, engineering, and math education

INTRODUCTION

Pathology is emerging from the Post-Genomics Era,[1] into the era of Personalized Medicine[2] and Big Data[3] and, as a result, the field will undergo a series of changes. We will redefine the way we engage in process sampling and analysis, requiring the use of interoperable imaging and molecular data. This will result in unprecedented need in information management, decision support and advanced analytics and herald the age of “computational pathology”. Institutions with strong scientific leadership in biomedical informatics and computational and systems biology will be key to the role of Pathology Informatics emerging in computational pathology. Despite this very bright future for Pathology (and Biomedical) Informatics, getting the best and the brightest individuals to fill these critical positions is challenging. The need to introduce bioinformatics at the high school level is rapidly gaining recognition.[4] Therefore, to address this important need for informatics savvy trainees we created the Computer Science, Biology, and Biomedical Informatics (CoSBBI) Track in the Summer Academy in 2011. CoSBBI is our effort to begin “pipelining” the best and the brightest high school students to informatics through a science, technology, engineering, and math (STEM) oriented research academy as part of the University of Pittsburgh Cancer Institute (UPCI) International Academy (see http://www.upci.upmc.edu/summeracademy/).

There are many summer programs for high school students including those at Johns Hopkins University (http://cty.jhu.edu/summer/), Stanford (https://summerinstitutes.stanford.edu/), Northwestern University (http://osep.northwestern.edu/), the Pennsylvania Governor's School (see http://www.pgssalumni.org/about-pgss) as well as many others across the US. When we began the UPCI Summer Academy in 2009, it aimed to improve upon the existing summer programs for high school students by providing a mentored hands-on primary research experience, including the usual didactics associated with most other programs. This was challenging and required the enlistment of many faculty, post-docs, medical students, and laboratory personnel to provide concentrated mentorship. The major innovation in the UPCI Summer Academy was not only to do primary meritorious work with a mentor, but also have students present their work orally. This was done with faculty, staff, and families invited to be in the audience for the oral PowerPoint presentations. It also included a judged scientific poster session presented to the entire scientific community of the UPCI on the last day of the academy. The results of this effort have been remarkable and have changed the career aspirations of many of the students who have participated. In 2011, after 3 years of the Department of Biomedical Informatics’ participation in the classroom component of the UPCI Summer Academy, we formed CoSBBI. Initially, CoSBBI was a partnership of the Departments of Biomedical Informatics (DBMI) and Computational and Systems Biology (CBS). Faculty from both departments provided mentored research experiences in computational biology, bioinformatics, biomedical informatics, and pathology informatics. It then ‘fissioned’, based on site changes, and gave rise to CoSBBI, more closely associated with the Department of Pathology and adjacent to the Hillman, and a new program oriented around drug discovery and systems biology for the past 3 years.

This editorial is a synopsis of that experience and encourages other programs to join us in this effort to create a pipeline of highest quality, research savvy trainees to our programs in pathology (and biomedical) informatics to ensure the successful integration of pathology (and computational pathologists) into the era of personalized medicine and big data.

HISTORY OF THE UPCI SUMMER ACADEMY

The UPCI Summer Academy was launched in 2009 and the Annual Reports since its inception can be downloaded at http://www.upci.upmc.edu/summeracademy/reports.cfm. These annual reports form the basis for the history of the UPCI International Academy (renamed in 2012) presented here (see also http://www.upci.upmc.edu/summeracademy/history.cfm).

Year 1-2009

The inaugural UPCI Summer Academy for Cancer Careers succeeded in its goals of encouraging students’ interest in cancer careers, instilling knowledge of cancer biology and clinical care, and developing research and communication skills. The initial program received seed funding from philanthropic and UPCI sources, and was launched with five talented and motivated students: Four rising high school seniors recruited from among PA Governor School applicants and one recent high school graduate. The students attended a series of cancer biology lectures presented by a UPCI clinician/researcher, a biology professor, and a University of Pittsburgh medical student. They also attended presentations by clinicians and researchers from across UPCI disciplines focusing on clinical care, career options, and career preparation. Students were led on tours of a variety of clinical and research facilities at UPCI and University of Pittsburgh Medical Center (UPMC) Shadyside. Most of each student's day was spent conducting laboratory research in a UPCI lab. This inaugural year taught us much and formed the basis for the next 4 years of the academy.

Years 2 through 4-2010-2012

In 2010 (year 2) we expanded the participation of underrepresented and disadvantaged/minority students by working closely with the Pittsburgh Public School system, the University of Pittsburgh's Office of Diversity, and national philanthropic programs, specifically the Jack Kent Cooke Foundation (JKCF). JKCF is a private, independent foundation established to help exceptionally promising scholars with modest family means reach their full potential through education. The academy also continued to receive support from local organizations such as the Pittsburgh Tissue Engineering Initiative and Bayer Material Sciences. Additionally, the academy was funded in early 2010 by a P30 CURE supplement from the National Cancer Institute. This grant enabled recruitment of under-represented minorities and under-represented students and provision of a $2,000 stipend and Robert Weinberg's “Biology of Cancer” textbook, allowing faculty mentors and laboratories to receive a $500 bench fee/supply stipend for their students’ projects. In 2010, the academy established a field trip to the National Cancer Institute (NCI) as a regular part of the program, which now included 10 scholars. In 2011, the program was expanded to two additional sites—CoSBBI and the Magee Women's Research Institute's Women's Cancer Research Center (WCRC), and had 24 high school students as scholars. The academy continued the unique partnership with JKCF. In 2012, the academy hosted three out-of-state scholars under the JKCF's Young Scholars Program to spend the summer in Pittsburgh: The Hillman Cancer Center hosted two of the scholars, and the third spent the summer working in computational systems biology with the CoSBBI program. In addition, the Academy received funding from the Doris Duke Charitable Foundation (DDCF). Over these years, enrolment in the program grew from 10 in 2010 to 24 in 2011 and 28 in 2012.

Year 5 - Refocusing the UPCI summer academy to the UPCI international academy

With success of the Academy we underwent a dramatic expansion to include 56 student scholars. This included the expansion to two new areas: The Drug Discovery, Systems, and Computational Biology (DiSCoBio) and Tumor Immunology, both in the Oakland campus. The DiSCoBio component formed its own program, geographically separate from CoSBBI, due to the logistical challenges posed by the move of the Department of Biomedical Informatics from Oakland to the Shadyside campus. In addition, in 2013 we recruited our first international students to the program and renamed the UPCI Summer Academy, the UPCI International Academy. Students from the 2013 class of scholars were selected from 143 applicants, and included recruits from Hawaii, New Jersey, Virginia, Minnesota, Texas, Vermont, New York, North Carolina, Maryland, Germany, and Kazakhstan.

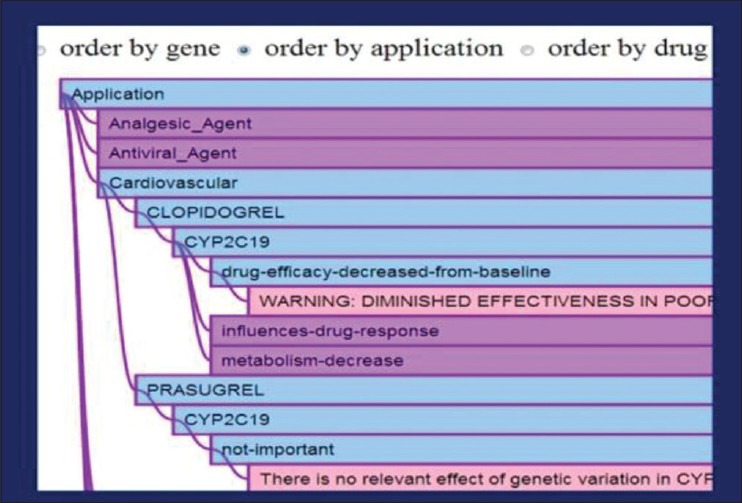

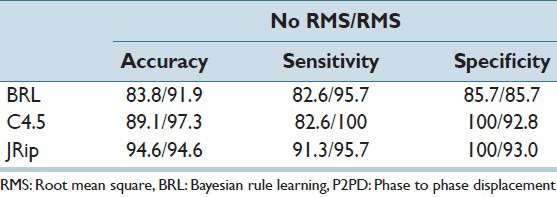

BACKGROUND ON COSBBI

The year 2013 was the third year of the CoSBBI Summer Academy. We enrolled a total of three (2011), seven (2012), and 11 (2013) high school students over the past three summers, and the number of mentors and number of students each mentor was willing to take on largely dictated this size. The 1st year was an experimental year, which turned out stellar students who went on to succeed in Intel Science Fair competitions regionally and nationally. We more than doubled the number of students the subsequent year, when CoSBBI was still co-located with the Department of CSB at the Oakland campus of the University of Pittsburgh. In 2013, CoSBBI was relocated to the Shadyside campus, and housed within the DBMI. CoSBBI students predominantly work on computational projects. We are able to take on younger students and have included seven sophomore high school students (rising juniors) thus far. We also partner with mentors from the Department of Pathology to provide experimental pathology projects focused on imaging informatics and next generation sequencing bioinformatics. In the class of 2013, we had five rising seniors and six rising juniors who developed and presented projects spanning a broad range of informatics topics including bioinformatics, computational biology, machine learning, image analysis, pharmacogenomics, and telemedicine.

A key component of the training that our students receive is from individual mentoring from outstanding scientists at the University of Pittsburgh's DBMI (see http://www.dbmi.pitt.edu/people) and Division of Pathology Informatics (see http://path.upmc.edu/cpi/). Research projects are usually prepared in advance by mentors when they are paired with the incoming high school student. Three publications from the mentor's laboratory or research area are sent to each trainee prior to the start of this 8-week academy. The scholars prepare to ask questions of the mentor regarding their specific project at the very start of their training. Some mentors also put two or three high school students onto the same project, providing them with adequate support for learning software programming and applying it to big datasets coming from genomic experiments. The role that mentors play is crucial to the success of the outcomes in terms of scholar satisfaction. Mentors often enlist postdoctoral and graduate students in their laboratories to provide additional support to enhance the learning experience of our CoSBBI scholars. On the final day of the academy, research mentors introduce their students to their colleagues, and the families of CoSBBI scholars are invited to attend. In the morning session, students describe their projects using an oral PowerPoint presentation. This is followed by a poster symposium at the Hillman Cancer Center in the afternoon. The afternoon session is open to the entire UPCI community and the public. Beginning in 2013, we will encourage the faculty research mentors and CoSBBI scholars to publish their abstracts in the Journal of Pathology Informatics (JPI) as part of our commitment to the hard work and energy these students bring to our laboratories and research projects each year.

Graduates from our summer program continue to stay in touch with their research mentors over the subsequent year to obtain recommendations for college applications, and to continue their research projects towards publication. All UPCI summer academy scholars are invited to present their posters during a reunion each year in early October, at a prestigious Science conference organized by the University of Pittsburgh, which brings together cutting-edge science and technology in the region. This experience has enabled our scholars to learn about their own research questions in the context of broader, related, and integrated scientific and engineering applications. Our past scholars have been admitted into honors colleges at prestigious national universities. Some universities that our scholars have accepted include: Duke University, Harvard University, Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), Penn State, Stanford University and University of Pennsylvania.

ROLE OF THE CLASSROOM COMPONENT

The classroom portion of CoSBBI was designed to provide a didactic introduction to biomedical informatics, promote an understanding of research, and expose students to career opportunities in this field. Towards this end, 4 weeks of daily lectures covered fundamental concepts and activities on information technology applied to biomedicine and health care. Each day was comprised of 1 instructional hour, led by doctoral, postdoctoral and medical students, followed by 1 hour of research presentation and discussion, led by faculty and industry guests. Lectures in the early weeks covered basics of molecular biology, bioinformatics tools, computational thinking, statistics, and data mining. In the absence of a standard undergraduate level textbook for our field, we selected the recently released compilation, Translational Bioinformatics (PLOS Computational Biology Collection, see syllabus). This online, open-access collection provided chapters crafted by leading experts in topics such as genomics, proteomics, Bayesian inference and decision modeling, and pharmacogenomics. These were complemented with lectures on human computer interaction and issues in technology incorporation for laboratory workflow, medication safety, and biosurveillance. The complete syllabus and links to PowerPoint presentations can be accessed at http://faculty.dbmi.pitt.edu/jod30/classes/cosbbi2013/. The classroom sessions were focused on concepts and application, with students encouraged to pursue deeper the skills relevant to their individual research project. Periodic sessions were held to discuss research progress, reading and presenting peer-reviewed papers, and writing an abstract.

Students in the CoSBBI program came with a background in advanced high school biology, but they varied in their mathematics and computational background, ranging from no programming experience to proficient in developing simple standalone applications. The students were administered a pre-test on the 1st day of class, consisting of multiple choice questions covering fundamentals from biology, genetics, protein interactions, computer science, bioinformatics, and biomedical informatics. The same test was again administered after the last day of class. Nine out of 11 students showed improvement in their scores, with a highest individual improvement rate of 83%. On an average, student performance increased by 26%.

IMPACT ON INFORMATICS - CREATING A PIPELINE

Biomedical Informatics training programs have existed since the 1970s[5] and our training program in Pittsburgh has been funded by the National Library Medicine since 1984 (see http://www.dbmi.pitt.edu/content/overview). Pathology informatics training has existed in the Division of the Department of Pathology at the University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine (UPSoM) since 1999 when we established the Center for Pathology Informatics (see http://path.upmc.edu/fellowship/informatics/index.htm). In both of these programs we recognize that we have had the opportunity to train excellent students. However, it is clear to us that the majority of recruits both in biomedical and pathology informatics come to our graduate training program with little relevant research experience and many decide on a career in informatics after training in other disciplines. At our Biomedical Informatics Training Program Retreat in 2012 we discussed this issue and found that only three of 113 people at the retreat had done relevant research in informatics during their high school and early college experiences. It turned out that those three people were the most widely cited authors and successful National Institute of Health (NIH) grant funded investigators in the group.

Spurred on by the successful launch of our high school student academy in 2011, we decided to establish a pipeline of the “best and the brightest” students and encourage them to pursue careers in informatics. The concept we sought to establish was to invite high school students to gain research experience and help them plan their college training to best prepare them for careers in informatics. We then established the following informatics directed “pipeline” plans which are in various stages of implementation today:

Recruit the best high school students (as early as sophomores) and provide mentored research experience via CoSBBI and establish a long-term relationship as their academic advisors

Offer CoSBBI scholars paid research assistant positions in informatics in our laboratories as summer employees through high school and while in college

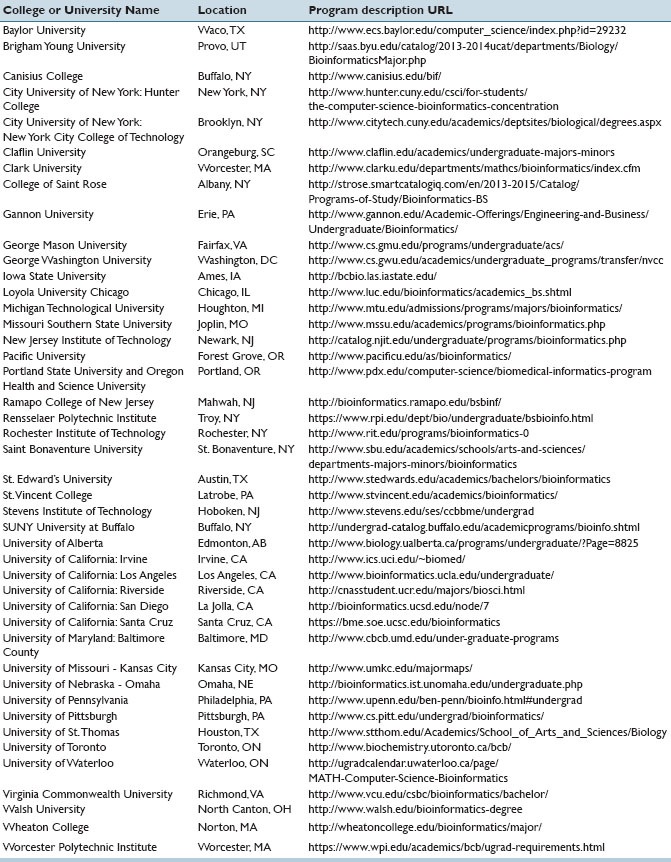

Encourage students applying for college to consider programs which have undergraduate degrees in bioinformatics [Table 1] and encourage them to take coursework in math, statistics, computer science, biology, as well as the study of human disease pathobiology

Emphasize to CoSBBI scholars the importance of publishing their work and to present at national pathology and informatics meetings (American Society for Clinical Pathology, American Medical Informatics Association, College of American Pathologists, and Pathology Informatics Summit). We also provide travel award scholarships

Foster a “virtual” community of high school and college trainees interested in informatics trainees through the establishment of a not for profit with this goal as its core mission.

Table 1.

Colleges and Universities Offering Undergraduate Degrees in Bioinformatics

This proposed pipeline has many moving parts of which the most important is the recruitment and retention of high quality trainees. The UPCI International Academy has reached out to many organizations and is developing both national and international reach. However, there are many competing summer programs and reaching high school students is very difficult, compared to recruiting college and graduate students. Developing a ‘viral’ program via social media, coupled with word-of-mouth via successful CoSBBI scholars, is our current focus. Aggressive Pittsburgh School system outreach and open-house programs have been very successful in providing regional coverage, but national coverage remains a challenge. Nonetheless, we are making steady progress by increasing the visibility of our trainees through their participation in national meetings and science fair programs such as the Intel Science and Engineering Fair (ISEF). We have had three of our CoSBBI alumni (out of 21 to date) qualify for the International ISEF after winning regional science fairs.

To distinguish our high school scholars and the research experience from other programs we have decided this year to publish the abstracts of their summer work in the JPI. JPI is the publication sponsored by the Association for Pathology Informatics (http://www.pathologyinformatics.org). We have decided that the best way to attract other innovative students is to feature the work of CoSBBI scholars in the literature. We leave this decision to publish the abstract to the scholar's faculty mentor. In this inaugural year of this enhancement to our program 10 of the 11 scholars abstracts were published and are included below. In addition, two of our students have presented their work at our national meeting the Pathology Informatics Summit (http://www.pathologyinformatics.com). Discussions are currently underway to sponsor a high school scholar's session at the annual meeting of the American Medical Informatics Association Meeting.

CONCLUSION

This editorial describes a Pittsburgh-based effort to create a pipeline of training opportunities in informatics starting with high school and continuing through college. We aim to attract the best and brightest high school students nationally and train them for informatics as CoSBBI scholars. As part of the program, the high school CoSBBI scholars participate in a 4-week formal didactic session and a mentored research project, culminating in a formal presentation to the scientific community, as well as to their families. This 8-week experience closes with a competitive poster symposium. We have now chosen to publish abstracts of the CoSBBI scholars (see accompanying prologue by Dr. Vanathi Gopalakrishnan, CoSBBI course director). Lastly, we have developed a plan for this pipeline which is being fully implemented in Pittsburgh by 2015, including the potential establishment of a 501c3 not-for-profit organization to support this effort and create the ‘virtual’ community needed for its success. Three organizations are planning to implement CoSBBI-like informatics oriented STEM initiatives in their institutions. The Pittsburgh team will share all of the materials it has assembled to assist other organizations in order to increase the number of trainees interested in informatics as a career. Transformation through education is a team sport … game on!!!

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We appreciate the partnership we are forming with the Departments of Biology and Computer Science at the University of Pittsburgh and want to thank the Chairs of those Departments, Daniel Mosse, PhD and Paula Grabowski, PhD. We also want to thank Andrew King, BS and Peter Randall (soon to be BS) who are graduates and current trainees in the University of Pittsburgh Bioinformatics undergraduate degree program. Andrew is the first graduate of this program that we have accepted into our PhD program in Biomedical Informatics. Special thanks to administrative and project management support from Lucy Cafeo, Nancy Whelan, Albert Geskin, and Linda Mignogna. We want to particularly thank Megan Seippel, Joe Ayoob, and many other helpful staff of the UPCI International (formerly Summer) Academy who have kept us on track each year for this important effort. This CoSBBI track of the UPCI International Academy is supported by NIH grants R01 LM010950 from the National Library of Medicine, R01 GM100387 from the National Institute of General Medical Sciences, Doris Duke Foundation, the National Cancer Institute CURE Program (3P30CA047904-22S1), and support from the Jack Kent Cook Foundation. In addition, this program would not be possible without the infrastructure and support teams from the DBMI NLM Training Program Grant in Biomedical Informatics (T15 LM007059), the University of Pittsburgh Cancer Institute (UPCI) Cancer Center Support Grant for the Cancer Bioinformatics Service (P30 CA47904), the Clinical and Translational Science Institute Biomedical Informatics Core (UL1 RR024153), as well as from funds and in-kind services from UPCI and DBMI, and the Departments of Surgery, Immunology, Computational and Systems Biology, Gynecology, and Pharmacology.

Footnotes

Available FREE in open access from: http://www.jpathinformatics.org/text.asp?2014/5/1/12/129448

REFERENCES

- 1.Becich MJ. The role of the pathologist as tissue refiner and data miner: The impact of functional genomics on the modern pathology laboratory and the critical roles of pathology informatics and bioinformatics. Mol Diagn. 2000;5:287–99. doi: 10.1007/BF03262090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hamburg MA, Collins FS. The path to personalized medicine. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:301–4. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1006304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mattmann CA. Computing: A vision for data science. Nature. 2013;493:473–5. doi: 10.1038/493473a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Machluf Y, Yarden A. Integrating bioinformatics into senior high school: Design principles and implications. Brief Bioinform. 2013;14:648–60. doi: 10.1093/bib/bbt030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mantas J, Ammenwerth E, Demiris G, Hasman A, Haux R, Hersh W, et al. MIA Recommendations on Education Task Force.Recommendations of the International Medical Informatics Association (IMIA) on Education in Biomedical and Health Informatics. First Revision. Methods Inf Med. 2010;49:105–20. doi: 10.3414/ME5119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]