Abstract

Brucellosis is a globally distributed zoonotic disease affecting animals and humans, and current antibiotic and vaccine strategies are not optimal. The surface-exposed protein Omp25 is involved in Brucella virulence and plays an important role in Brucella pathogenesis during infection, suggesting that Omp25 could be a useful target for selecting potential therapeutic molecules to inhibit Brucella pathogenesis. In this study, we identified, we believe for the first time, peptides that bind specifically to the Omp25 protein of pathogens, using a phage panning technique, After four rounds of panning, 42 plaques of eluted phages were subjected to pyrosequencing. Four phage clones that bound better than the other clones were selected following confirmation by ELISA and affinity constant determination. The peptides selected could significantly inhibit Brucella abortus 2308 (S2308) internalization and intracellular growth in RAW264.7 macrophages, and significantly induce secretion of TNF-α and IL-12 in peptide- and S2308-treated cells. Any observed peptide (OP11, OP27, OP35 or OP40) could significantly inhibit S2308 infection in BALB/c mice. Moreover, the peptide OP11 was the best candidate peptide for inhibiting S2308 infection in vitro and in vivo. These results suggest that peptide OP11 has potential for exploitation as a peptide drug in resisting S2308 infection.

Introduction

Bacteria of the genus Brucella are Gram-negative and facultative intracellular pathogens that pose threats to animal and human health throughout the world. The main pathogenic species worldwide are Brucella abortus and Brucella melitensis, which can cause abortions and infertility in cattle and sheep, resulting in heavy economic losses. Human disease is also caused by B. melitensis, B. abortus and Brucella suis. Infection in humans can cause fever, arthritis, spondylitis, dementia and meningitis, or endocarditis under rare circumstances (Elzer et al., 2002; Godfroid et al., 2005; Hamdy et al., 2002).

Brucella spp. contain three groups of major outer-membrane proteins (Omps) (Dubray & Bézard, 1980; Verstreate et al., 1982). The group 3 outer-membrane proteins consist of two related proteins of 25 (Omp25) and 31 (Omp31) kDa (Cloeckaert et al., 1996; Vizcaíno et al., 1996). Analysis of the omp25 gene indicates that it is highly conserved in Brucella spp., biovars and strains (Cloeckaert et al., 1995). Omp25 proteins are surface-exposed proteins known to be involved in Brucella virulence, and play an important role in the attachment or invasion to the host cell. Omp25 mutants of B. melitensis, B. abortus and Brucella ovis strains have been found to be attenuated in mice, goats (B. melitensis) and cattle (B. abortus) (Edmonds et al., 2001, 2002a, b).

The phage display technique was established by Smith (1985) and has been proven to be a powerful tool for studying protein–protein interactions, including host–pathogen interactions, bacterial adhesins and receptor–ligand interactions (Bair et al., 2008; Pande et al., 2010). A phage random peptide library contains a pool of billions of peptides produced by the fusion of random nucleic acid sequences to the N terminus of one of the capsid protein genes (pVIII or pIII) of a filamentous bacteriophage (Cwirla et al., 1990; Devlin et al., 1990; Scott & Smith, 1990). The most important feature of this technique is the direct link between the experimental phenotype and its encapsulated genotype (Azzazy & Highsmith, 2002). Phage display is now playing an important role in the discovery of peptides and antibodies that may serve as novel therapeutics (Nelson et al., 2010; Fjell et al., 2012).

In this study, we identified, we believe for the first time, peptides that bind specifically to the Omp25 protein of pathogenic Brucella abortus 2308 using a phage panning technique. Our results showed that the peptide OP11 was the most effective at inhibiting S2308 infection compared with three other selected peptides (OP27, OP35 and OP40) in vitro and in vivo, which may be useful for developing new drugs against Brucella infections.

Methods

Recombinant Omp25 and 32A expression and purification.

The Omp25 ORFs were amplified by PCR from the S2308 genome. Primer design was based on S2308. Primer sequences for the omp25 gene (642 bp) were as follows: sense primer, 5′-GAATTCATGCGCACTCTTAAGTCTCTCGTA-3′ (EcoRI site underlined) and antisense primer, 5′-GTCGACTTAGAACTTGTAGCCGATGC-3′ (SalI site underlined). The amplified omp25 gene was then cloned into the pET32a vector (Novagen) to generate the recombinant plasmid pET32a-Omp25. The recombinant plasmid pET32a-Omp25 was then transformed into cells of Escherichia coli BL21(DE3). Expression of recombinant protein was induced with 1 mM IPTG generating N-terminally His-tagged fusion proteins. The recombinant proteins (45.4 kDa) expressed from pET32a-Omp25 were purified by affinity chromatography with Ni(II)-conjugated Sepharose and concentrated by using Centricon 3 concentrators (Amicon). The pET32a empty vector was also transformed separately into cells of E. coli BL21(DE3), and the protein (32A, 20.4 kDa) containing the thioredoxin and histidine fusion tag alone was expressed and purified using the method above, as a control. The two proteins were confirmed by SDS-PAGE. Total protein assays were carried out using a bicinchoninic acid (BCA) protein assay kit (Pierce).

Biopanning procedure.

A cyclic 7-mer random peptide library (from New England BioLabs) was used in this study. Biopanning was performed by coating a micro-plate well with 200 µl of purified Omp25 at a concentration of 40 µg ml−1 in 0.1 M NaHCO3 (pH 8.6) at 4 °C overnight in a humidified container. The wells were then blocked with 200 µl of blocking solution (0.5 % BSA+0.1 M NaHCO3, w/v, pH 8.6) at 37 °C for 1 h. The phage library Ph.D.-C7C was added at 2×1011 p.f.u. per well in 100 µl of wash buffer [1× Tris-buffered saline (TBS)+0.1 % (v/v) Tween 20; TBST] and incubated for 1 h at 37 °C with gentle agitation. The wells were washed ten times with wash buffer to remove unbound phages. Bound phages were eluted with 200 µl 0.2 M glycine-hydrochloride (pH 2.2) for 10 min at room temperature and neutralized with 20 µl 1 M Tris (pH 9.1). The eluted phage were titrated and used to infect E. coli ER2738 cells for amplification for the next round of panning. Four rounds of panning were performed.

Phage titre calculation.

E. coli ER2738 was inoculated and grown at 37 °C to mid-exponential phase (OD600~0.5). Tenfold serial dilutions of phage-containing suspension were prepared in LB medium (101 to 104 for unamplified panning eluates, 108 to 1011 for amplified cell culture supernatants). Ten microlitres of each phage dilution was added to 200 µl of mid-exponential phase E. coli ER2738 and incubated with 4.0 ml molten top agar (45 °C) for 5 min. Infected cells were mixed with preheated agarose top, poured onto prewarmed (37 °C) LB/IPTG/X-Gal plates, and cooled at room temperature for 10 min, then incubated overnight at 37 °C. Phage titres were calculated by multiplying the number of blue plaques by the dilution factor.

Plaque amplification.

An overnight culture of E. coli ER2738 was diluted 1 : 100 in LB and 200 µl was dispensed into each well of a microtitre plate. Individual blue plaques were transferred to each well and incubated at 37 °C for 5 h with shaking. The microtitre plates were centrifuged at 6000 g for 15 min at 4 °C and the upper 80 % of phage-containing supernatant was collected and stored at 4 °C.

Phage ssDNA extraction.

Selected amplified phage (1 ml) from individual clones were transferred to a fresh microcentrifuge tube. PEG-NaCl (400 µl) was added and tubes were incubated at room temperature for 10 min. After centrifugation (15 000 g at 4 °C for 15 min), the supernatant was discarded and the pellet was suspended thoroughly in 100 µl iodide buffer [10 mM Tris/HCl (pH 8.0), 1 mM EDTA, 4 M NaI]. Then, 250 µl ethanol was added. The mixtures were incubated for 10 min at room temperature. The mixture was centrifuged at 15 000 g for 15 min and the supernatant was discarded. The pellet was washed with 70 % ethanol, dried and suspended in 40 µl sterile double-distilled water.

Nucleotide sequencing.

DNA content was verified by electrophoresis on agarose gels. ssDNA of individual isolated phage clones was purified according to the manufacturer’s protocol using a Qiagen miniprep kit and then sequenced with the −96gIII sequencing primer (New England Biolabs), performed by Sangon Biotech (Shanghai, China).

ELISA with isolated phage clones.

The purified fusion proteins Omp25 and 32A were applied to 96-well microtitre plates (Nunc) (10 µg per well) and incubated overnight at 4 °C. Unbound proteins were removed and the wells were blocked with blocking buffer (TBST containing 3 % BSA) at 37 °C for 1 h. Selected phage clones (1×1010 per well) were added and incubated for 1.5 h at 37 °C. Unbound phage was removed by washing (PBS/0.05 % Tween 20) five times for 3 min. Peroxidase-labelled anti-M13-phage antibody was added for another hour. After washing four times with washing buffer, the reaction was visualized with 2,2′-azino-bis(3-ethylbenzothiazoline-6-sulfonic acid) (ABTS; Sigma) and optical density read at 450 nm.

Affinity constant determination.

The affinity constant (Kaff) of peptides (OP11, OP27, OP35 and OP40) was determined by a previously described method using a solid-phase non-competitive enzyme immunoassay (Beatty et al., 1987).

MTT assay.

RAW264.7 macrophages were seeded at 1×104 cells ml−1 in 96-well plates and cells were washed three times with PBS at 0, 12, 24 and 48 h after incubation with OP11, OP27, OP35 and OP40 peptides (20 µM), and assessed for cell viability using 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT; Sigma). Fifty microlitres of MTT was added to each well and incubated at 37 °C for 4 h. The supernatant was then removed and 100 µl DMSO (Sigma) was added to each well. Optical density was determined by eluting the dye with DMSO, and the absorbance was measured at 570 nm. Three independent experiments were performed.

Cell test.

Murine macrophage RAW264.7 cells were obtained from the Type Culture Collection of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (Shanghai, China) and were cultured in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s Medium (DMEM; Gibco) supplemented with 10 % fetal bovine serum (FBS; Gibco). Cells were routinely cultured at 37 °C in a 5 % CO2 atmosphere. To analyse the effect of peptides on S2308 internalization, RAW264.7 cells in six-well plates were incubated with peptides (10 µM) and S2308 (100 m.o.i.) at 37 °C for 30 and 45 min. Cells were washed once with medium and then incubated with DMEM containing gentamicin (30 µg ml−1) for 30 min to kill any remaining extracellular and adherent bacteria. The cells were washed three times with PBS and lysed, and the live bacteria were enumerated by plating on TSA (Difco, Becton Dickinson) plates. To determine the effect of peptides on S2308 intracellular growth, the infected cells were incubated at 37 °C for 40 min, and the medium was then replaced with DMEM, peptides and gentamicin, and incubated for 4, 24 and 48 h. Cell washing, lysis and plating procedures were the same as for the analysis of S2308 internalization. At 12 and 24 h post-infection, the levels of TNF-α and IL-12 in the supernatants were measured using an ELISA Quantikine Mouse kit (R&D Systems). Three independent experiments were performed.

Mice experiments.

All six-week-old female BALB/c mice were obtained from the Experimental Animal Center of the Academy of Military Medical Science (Beijing, China). The mice were divided into six groups (10 mice per group). Experimental groups of mice were separately injected subcutaneously with S2308 (1×106 c.f.u. per mouse) and one of the peptides OP11, OP27, OP35 or OP40 (200 µg per mouse), and the control group was injected with S2308 (1×106 c.f.u. per mouse) and PBS (200 µl per mouse). At weeks 2, 5 and 7, experimental groups of mice were given one of the peptides (200 µg per mouse) and control groups were given PBS (200 µl per mouse) by subcutaneous injection. At 3, 6 and 9 weeks, the mice were euthanized and their spleens were removed aseptically. The spleens were collected aseptically for quantification of bacterial burden, and spleens and bodies were weighed. The ratio of spleen weight to body weight was then calculated. Spleens from individual mice were homogenized in sterile saline, 10-fold serially diluted, and plated on TSA. Plates were incubated at 37 °C and the number of c.f.u. was counted after 3 days. The experiments were repeated three times with similar results.

Statistical analysis.

The data were analysed using Student’s t-test and were expressed as mean±sem. P values of <0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

Recombinant Omp25 expression and purification

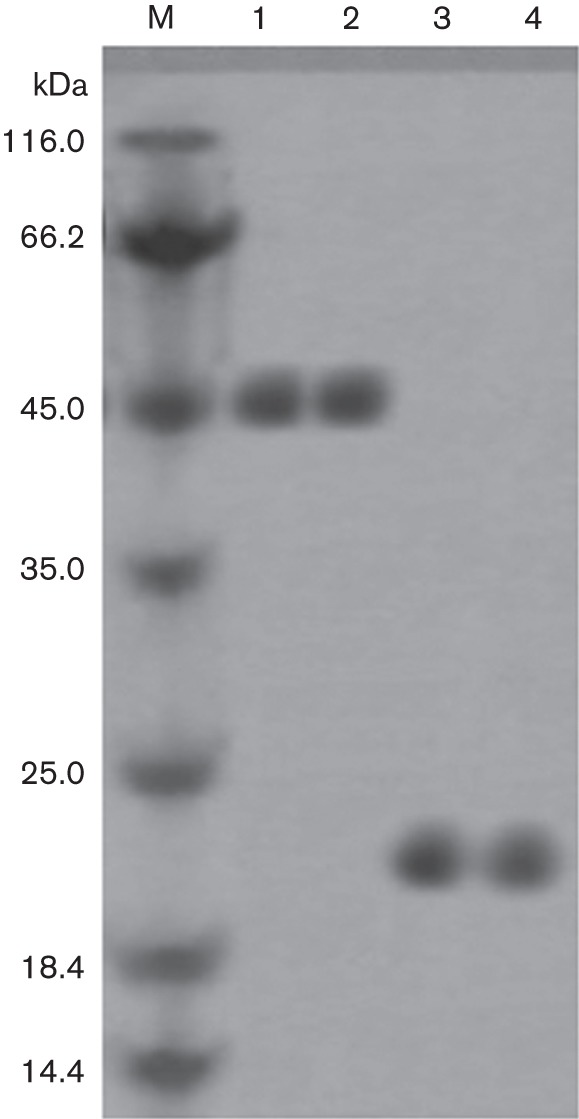

After induction with IPTG (1.0 mM) at 37 °C for 4 h, E. coli BL21(DE3) harbouring pET32a-Omp25 or pET32a exhibited a high level of expression (data not shown). The recombinant Omp25 protein was purified using a Ni-NTA affinity column. The 32A protein (20.4 kDa) expressed by pET32a empty vector was also purified as described above. Two clear target bands of approximately 46 kDa and 20 kDa were visible (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Purification of recombinant Omp25 and 32A proteins. Purified recombinant Omp25 (lanes 1–2) and 32A (lanes 3–4) proteins were detected by SDS-PAGE. M, molecular mass marker.

Phage display screening

In order to identify peptides that specifically bind to Omp25, four rounds of biopanning were performed using a random cyclic 7-mer peptide library. A gradual increase in enriched phage from 5.5×104 to 2×108 p.f.u. was monitored after each round of panning for the antigen (Table 1). Forty-two phage clones were randomly picked from the fourth round output phages and were subjected to sequencing and more analysis.

Table 1. Phage display titrating result and recovery rate of phages bound to Omp25 protein.

| Round | ||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | |

| Input phage (p.f.u.) | 2×1011 | 2×1011 | 2×1011 | 2×1011 |

| Output phage (p.f.u.) | 5.5×104 | 8×105 | 9×107 | 2×108 |

| Recovery rate | 2.75×10−7 | 4×10−6 | 4.5×10−4 | 1×10−3 |

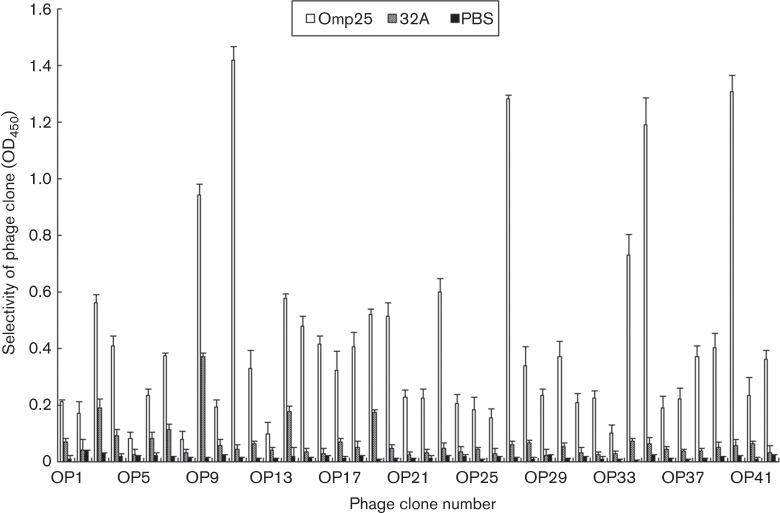

In vitro confirmation of binding

In order to confirm the binding ability of selected phage clones to Omp25, 42 independent phage clones, which were randomly picked after the fourth in vitro panning, were tested by ELISA, and 32A protein and PBS were used as a control. Phage clones OP11, OP27, OP35 and OP40 appeared to bind better than the other clones (Fig. 2). When the sequences of these phage clones were analysed by DNA sequencing, it was shown that OP11, OP27, OP35 and OP40 contained the peptide sequences TTSLKTF, STPSSQT, MSPSSNT and SLTTSSN (Table 2), respectively, and they had a similarity of 47.22 % to each other when analysed using the software dnaman with default parameters and the clustal w algorithm for multiple sequence alignment. Moreover, the affinity constants (Kaff) of the different peptides were measured (Table 3), and were consistent with the results of ELISA.

Fig. 2.

Evaluation of the binding selectivity of 42 phage clones by ELISA. PBS and 32A protein were used as control. OD450 was obtained after blocking of the reaction. The selectivity of every phage clone was calculated using the formula described previously (Du et al., 2006). Data represent means ±SD of three independent experiments with similar results.

Table 2. Alignment of selective peptide sequences.

| Phage clone | Amino acid sequence | Frequency* |

| OP11 | TTSLKTF | 1 |

| OP27 | STPSSQT | 1 |

| OP35 | MSPSSNT | 1 |

| OP40 | SLTTSSN | 1 |

Number of times this particular clone was obtained from a random selection of clones sequenced. Bold letters represent similar amino acids when compared using the DNAMAN software.

Table 3. Affinity constants (Kaff) of the selected peptides.

| Peptide | Kaff constant |

| OP11 | 7.05×10−9 |

| OP27 | 5.98×10−9 |

| OP35 | 4.93×10−9 |

| OP40 | 6.42×10−9 |

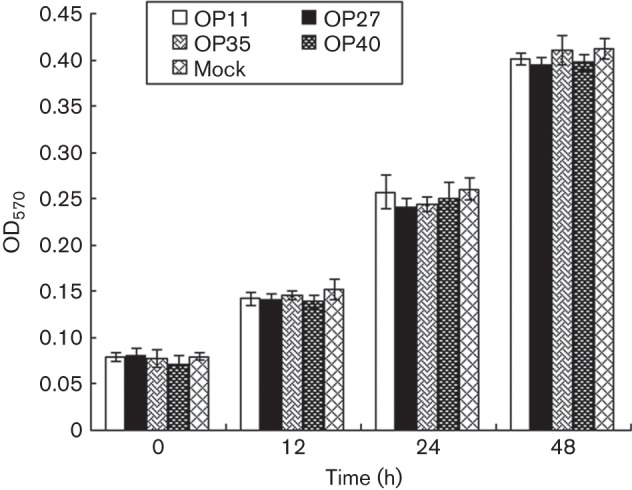

Effects of peptides on the growth of RAW264.7 macrophages

We next investigated whether the TTSLKTF, STPSSQT, SLTTSSN and MSPSSNT peptides affected the growth of RAW264.7 macrophages. The cell viability of RAW264.7 macrophages incubated with peptides (20 µM) was analysed by MTT assay at 0, 12, 24 and 48 h. There was no loss of viability of the peptide-treated macrophages compared with that of control cells (P>0.05; Fig. 3). These results suggested that these peptides do not affect the survival of RAW264.7 macrophages.

Fig. 3.

The effect of peptides (20 µM) on viability of RAW264.7 macrophages analysed by MTT assay. Cell viability was determined by measuring OD570. Data represent means ±SD of three independent experiments with similar results.

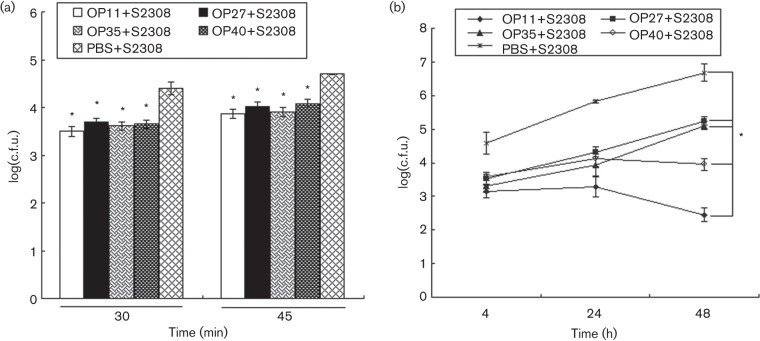

Inhibition of S2308 infection by peptides in RAW264.7 macrophages

The mixtures of S2308 and peptides were incubated with macrophages to test whether the selected peptides inhibited S2308 internalization and intracellular growth. At 30 min post-infection, a significant (P<0.01) reduction in S2308 internalization was observed inside macrophages treated with OP11 (87.41 %), OP27 (80.05 %), OP35 (83.78 %) and OP40 (82.22 %) with respect to that of control cells, and similar results were obtained at 45 min post-infection (Fig. 4a). In contrast, no significant differences were found in the S2308 internalization capacity of OP11-, OP27-, OP35- and OP40-treated macrophages.

Fig. 4.

Evaluation of S2308 internalization and intracellular growth inhibited by selected peptides. RAW264.7 macrophages were infected with S2308 as a control. Bacterial internalization (a) and bacterial intracellular growth (b) were determined at different infection times. Significant differences between the number of S2308 c.f.u. for peptide-treated macrophages and the controls are indicated as follows: *P<0.01. Data represent means ±SD of three independent experiments with similar results.

For the intracellular replication assay, at 4 h post-infection, a 1.43-log, 1.03-log, 1.26-log and 1.01-log decrease (P<0.01) was observed in the bacteria number of S2308 replication inside OP11-, OP27-, OP35- and OP40-treated macrophages, respectively, compared with that of control cells. At 48 h post-infection, the decreases inside the peptide-treated macrophages were even greater at 4.23-log, 1.44-log, 1.57-log and 2.73-log, respectively (P<0.01; Fig. 4b). Moreover, the number of S2308 c.f.u. inside OP11-treated macrophages was significantly reduced compared to that of OP27-, OP35- and OP40-treated macrophages at 48 h post-infection (P<0.01; Fig. 4b).

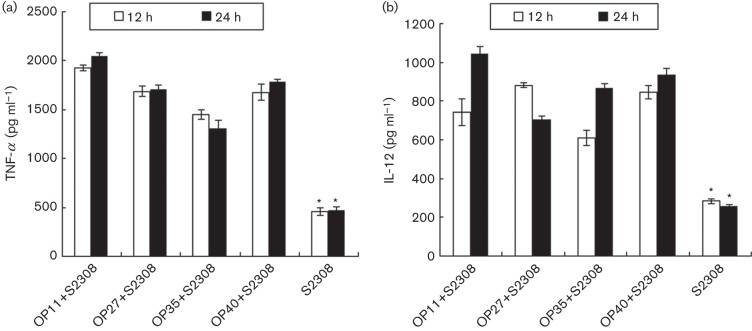

Cytokine response induced by S2308-infected peptide-treated RAW264.7 macrophages

Peptides mixed with S2308 were incubated with macrophages to assess the peptides’ abilities to induce a cytokine response on S2308-infected cells. The levels of TNF-α (Fig. 5a) and IL-12 (Fig. 5b) were assessed in supernatants of S2308-infected peptide-treated macrophages. At 12 and 24 h, all peptide- plus S2308-treated macrophages produced significantly higher levels of TNF-α and IL-12 compared with S2308-infected cells (P<0.001). In addition, OP11- and S2308-treated macrophages exhibited higher levels of TNF-α and IL-12 than those treated with the other peptides at 24 h. The results showed that OP11, OP27, OP35 and OP40 could induce the proinflammatory cytokines TNF-α and IL-12 in S2308-infected macrophages, and the activity of OP11 appeared to be greater than that of OP27, OP35 and OP40.

Fig. 5.

Analysis of TNF-α (a) and IL-12 (b) secretion from the supernatant of peptide- and S2308-treated macrophages, measured by ELISA. Significant differences of OP11- and S2308-treated macrophages from S2308-treated macrophages are indicated as follows: *P<0.001. Data represent means ±SD of three independent experiments with similar results.

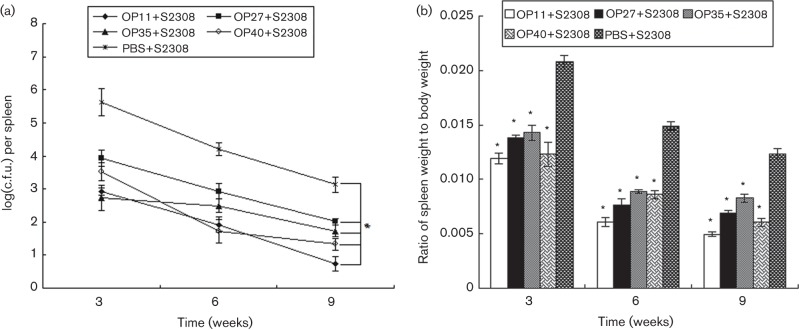

Inhibition effect of S2308 infection by peptides in mice

To further evaluate whether OP11, OP27, OP35 and OP40 peptides could inhibit S2308 infection in BALB/c mice, 1×106 c.f.u. of S2308 was separately and simultaneously injected into mice with either OP11, OP27, OP35 or OP40 peptides or PBS as a control. The number of S2308 c.f.u. was evaluated at 3, 6 and 9 weeks in the spleen of each animal. In spleen, the bacterial load was significantly reduced in mice injected with any of the peptides at all times observed compared with that of the PBS group (P<0.001), and was lowest in mice injected with OP11 peptide at 9 weeks (Fig. 6a). The ratio of spleen weight to body weight was significantly smaller in mice injected with any of the peptides than in the PBS group (P<0.001), and was smallest in mice injected with OP11 peptide, as shown by the lack of splenomegaly (Fig. 6b).

Fig. 6.

Inhibition effect of peptides on S2308 infection in mice. BALB/c mice were injected with S2308 and peptides as described in Methods. At 3, 6 and 9 weeks post-infection, the spleens were harvested and individual spleens (a) were assessed for colonization and ratio of spleen weight to body weight (b). Significant differences of the number of S2308 c.f.u. in peptide-treated mice compared with PBS-treated control mice are indicated as follows: *P<0.001. Data represent means ±SD of three independent experiments with similar results.

Discussion

Phage display has been widely used to identify specific peptides and antibodies against pathogen targets, and applied successfully to cancer research, drug discovery and infectious diseases (Huang et al., 2012). Antigens on the cell surface of pathogens are appealing targets for biologics because they provide potential binding sites for molecules to interfere with colonization and virulence (Rasko & Sperandio, 2010). Phage-displayed peptides or proteins have been investigated as drug candidates against infections caused by bacteria and viruses, including Salmonella typhi, white spot syndrome virus and Staphylococcus aureus (Wu et al., 2005; Yi et al., 2003; Yang et al., 2003).

We used the cyclic peptide phage library for several reasons (Das & Meirovitch, 2001; Maraganore et al., 1990; Priestle et al., 1993). Firstly, cyclic peptides are generally more stable and more resistant to proteolysis than linear peptides. Moreover, a ligand sequence, where the imposed constraint allows for a productive binding conformation, will bind more tightly than the same linear sequence due to improved binding entropy. Currently, the only difffference between the 12-mer and 7-mer phage library is the efficiency of phage amplification (Du et al., 2006). The positive clones from cyclic 7-mer phages could have a better binding ability than linear 12-mer phages (Luo et al., 2004). The Omp25 protein is a highly conserved protein with seven epitopes on the surface of the membrane, as analysed by dnaman software, and the antigenic regions are hydrophilic in the β-fold region. In our study, the seven amino acids of four selected peptides were also almost hydrophilic. We employed the cyclic 7-mer phage library with the Omp25 protein as the target for affinity selection and obtained a peptide ligand which inhibited bacterial adhesion to and invasion of RAW264.7 macrophages. We speculate the selected peptides may be surface receptors on the macrophages.

In this study, we used the cyclic 7-mer random Ph.D.-C7C phage-displayed peptide library screening as a way to identify small and easily synthesizable peptides that specifically bind to the Omp25 protein. After four rounds of panning, 42 clones were chosen for further characterization. First, we used ELISA to confirm specific binding of Omp25 protein in vitro (Fig. 2). The best four candidate clones, OP11, OP27, OP35 and OP40, were then selected for further research. Next, the affinity constants (Kaff) of the different peptides were measured to further confirm their binding ability (Table 3). The bound phages were picked at random for DNA sequencing. Analysis of amino acid sequences of peptide inserts from selected phage clones indicated that the overall sequence homology was limited (Table 2). The best candidate clone, OP11 peptide, inhibited the proliferation of bacteria in vitro, and when OP11 peptides were injected into mice, infection was attenuated. These experiments confirmed that OP11 peptide could protect animals from S2308 infection by reducing the pathogenic potential of the bacteria.

TNF-α is an essential cytokine required for protection against pathogens, and increases the intracellular killing of pathogens by macrophages (Chatterjee et al., 1992; Sharma et al., 2006). In Brucella-infected macrophages, Omp25 is specifically involved in the inhibition of TNF-α production, and the absence of Omp25 promoted the secretion of TNF-α (Jubier-Maurin et al., 2001). IL-12 can efficiently induce the production of IFN-γ by both resting and activated T-cells and natural killer (NK) cells, and enhances the cytolytic activity of a number of effector cells (T-cells, NK cells and macrophages) and stimulates the proliferation of activated T-cells and NK cells (Biron & Gazzinelli, 1995; Manetti et al., 1993). IL-12 plays an important role in potent T-cell-dependent protection against infection with intracellular pathogens (Sharma et al., 2006). Our results showed that peptide-treated macrophages produced significantly higher levels of TNF-α and IL-12 compared with mock-infected cells. It is possible that the peptides inhibit the function of Omp25, resulting in high-level production of TNF-α. High levels of IL-12 may be associated with attenuation of S2308 virulence. High levels of TNF-α and IL-12 give rise to cell-mediated immunity to Brucella infection. The inhibition efficiency of the candidate clone OP11 peptide was higher than that of the other clones in vitro and in vivo. The results suggest that peptide OP11 has potential for exploitation as an anti-Brucella peptide drug.

In conclusion, we have obtained peptide sequences that recognize the Omp25 protein using a phage display library. The best candidate clone, OP11 peptide, could inhibit S2308 infection in vitro and in vivo, and also elicit cellular immune responses. To our knowledge this is the first report of peptide ligands specific for the protein Omp25 of B. abortus 2308. Our study may be useful for developing new drugs against Brucella infections, including prevention and therapeutic treatment.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by grants from the National Basic Research Program of China (973 Program) (2010CB530203) and National Twelfth Five-Year Plan for Science & Technology Support Program (2013BAI05B05) and International Cooperation in Science and Technology (2013DFA32380) and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (31201863, 81360239).

References

- Azzazy H. M., Highsmith W. E., Jr (2002). Phage display technology: clinical applications and recent innovations. Clin Biochem 35, 425–445 10.1016/S0009-9120(02)00343-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bair C. L., Oppenheim A., Trostel A., Prag G., Adhya S. (2008). A phage display system designed to detect and study protein-protein interactions. Mol Microbiol 67, 719–728 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2007.06077.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beatty J. D., Beatty B. G., Vlahos W. G. (1987). Measurement of monoclonal antibody affinity by non-competitive enzyme immunoassay. J Immunol Methods 100, 173–179 10.1016/0022-1759(87)90187-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biron C. A., Gazzinelli R. T. (1995). Effects of IL-12 on immune responses to microbial infections: a key mediator in regulating disease outcome. Curr Opin Immunol 7, 485–496 10.1016/0952-7915(95)80093-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chatterjee D., Roberts A. D., Lowell K., Brennan P. J., Orme I. M. (1992). Structural basis of capacity of lipoarabinomannan to induce secretion of tumor necrosis factor. Infect Immun 60, 1249–1253 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cloeckaert A., Verger J. M., Grayon M., Grépinet O. (1995). Restriction site polymorphism of the genes encoding the major 25 kDa and 36 kDa outer-membrane proteins of Brucella. Microbiology 141, 2111–2121 10.1099/13500872-141-9-2111 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cloeckaert A., Verger J. M., Grayon M., Vizcaíno N. (1996). Molecular and immunological characterization of the major outer membrane proteins of Brucella. FEMS Microbiol Lett 145, 1–8 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1996.tb08547.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cwirla S. E., Peters E. A., Barrett R. W., Dower W. J. (1990). Peptides on phage: a vast library of peptides for identifying ligands. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 87, 6378–6382 10.1073/pnas.87.16.6378 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Das B., Meirovitch H. (2001). Optimization of solvation models for predicting the structure of surface loops in proteins. Proteins 43, 303–314 10.1002/prot.1041 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devlin J. J., Panganiban L. C., Devlin P. E. (1990). Random peptide libraries: a source of specific protein binding molecules. Science 249, 404–406 10.1126/science.2143033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Du B., Qian M., Zhou Z., Wang P., Wang L., Zhang X., Wu M., Zhang P., Mei B. (2006). In vitro panning of a targeting peptide to hepatocarcinoma from a phage display peptide library. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 342, 956–962 10.1016/j.bbrc.2006.02.050 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dubray G., Bézard G. (1980). Isolation of three Brucella abortus cell-wall antigens protective in murine experimental brucellosis. Ann Rech Vet 11, 367–373 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edmonds M. D., Cloeckaert A., Booth N. J., Fulton W. T., Hagius S. D., Walker J. V., Elzer P. H. (2001). Attenuation of a Brucella abortus mutant lacking a major 25 kDa outer membrane protein in cattle. Am J Vet Res 62, 1461–1466 10.2460/ajvr.2001.62.1461 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edmonds M. D., Cloeckaert A., Elzer P. H. (2002a). Brucella species lacking the major outer membrane protein Omp25 are attenuated in mice and protect against Brucella melitensis and Brucella ovis. Vet Microbiol 88, 205–221 10.1016/S0378-1135(02)00110-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edmonds M. D., Cloeckaert A., Hagius S. D., Samartino L. E., Fulton W. T., Walker J. V., Enright F. M., Booth N. J., Elzer P. H. (2002b). Pathogenicity and protective activity in pregnant goats of a Brucella melitensis Δomp25 deletion mutant. Res Vet Sci 72, 235–239 10.1053/rvsc.2002.0555 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elzer P. H., Hagius S. D., Davis D. S., DelVecchio V. G., Enright F. M. (2002). Characterization of the caprine model for ruminant brucellosis. Vet Microbiol 90, 425–431 10.1016/S0378-1135(02)00226-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fjell C. D., Hiss J. A., Hancock R. E., Schneider G. (2012). Designing antimicrobial peptides: form follows function. Nat Rev Drug Discov 11, 37–51 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Godfroid J., Cloeckaert A., Liautard J. P., Kohler S., Fretin D., Walravens K., Garin-Bastuji B., Letesson J. J. (2005). From the discovery of the Malta fever’s agent to the discovery of a marine mammal reservoir, brucellosis has continuously been a re-emerging zoonosis. Vet Res 36, 313–326 10.1051/vetres:2005003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamdy M. E., El-Gibaly S. M., Montasser A. M. (2002). Comparison between immune responses and resistance induced in BALB/c mice vaccinated with RB51 and Rev. 1 vaccines and challenged with Brucella melitensis bv. 3. Vet Microbiol 88, 85–94 10.1016/S0378-1135(02)00088-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang J. X., Bishop-Hurley S. L., Cooper M. A. (2012). Development of anti-infectives using phage display: biological agents against bacteria, viruses, and parasites. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 56, 4569–4582 10.1128/AAC.00567-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jubier-Maurin V., Boigegrain R. A., Cloeckaert A., Gross A., Alvarez-Martinez M. T., Terraza A., Liautard J., Köhler S., Rouot B. & other authors (2001). Major outer membrane protein Omp25 of Brucella suis is involved in inhibition of tumor necrosis factor alpha production during infection of human macrophages. Infect Immun 69, 4823–4830 10.1128/IAI.69.8.4823-4830.2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo H. B., Zheng S. G., Zhu P., Fu N. (2004). [Study on mimotopes of E. coli lipopolysaccharide 2630]. Xibao Yu Fenzi Mianyixue Zazhi 20, 682–685 (in Chinese). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manetti R., Parronchi P., Giudizi M. G., Piccinni M. P., Maggi E., Trinchieri G., Romagnani S. (1993). Natural killer cell stimulatory factor (interleukin 12 [IL-12]) induces T helper type 1 (Th1)-specific immune responses and inhibits the development of IL-4-producing Th cells. J Exp Med 177, 1199–1204 10.1084/jem.177.4.1199 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maraganore J. M., Bourdon P., Jablonski J., Ramachandran K. L., Fenton J. W., II (1990). Design and characterization of hirulogs: a novel class of bivalent peptide inhibitors of thrombin. Biochemistry 29, 7095–7101 10.1021/bi00482a021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson A. L., Dhimolea E., Reichert J. M. (2010). Development trends for human monoclonal antibody therapeutics. Nat Rev Drug Discov 9, 767–774 10.1038/nrd3229 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pande J., Szewczyk M. M., Grover A. K. (2010). Phage display: concept, innovations, applications and future. Biotechnol Adv 28, 849–858 10.1016/j.biotechadv.2010.07.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Priestle J. P., Rahuel J., Rink H., Tones M., Grütter M. G. (1993). Changes in interactions in complexes of hirudin derivatives and human α-thrombin due to different crystal forms. Protein Sci 2, 1630–1642 10.1002/pro.5560021009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rasko D. A., Sperandio V. (2010). Anti-virulence strategies to combat bacteria-mediated disease. Nat Rev Drug Discov 9, 117–128 10.1038/nrd3013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott J. K., Smith G. P. (1990). Searching for peptide ligands with an epitope library. Science 249, 386–390 10.1126/science.1696028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma A., Saha A., Bhattacharjee S., Majumdar S., Das Gupta S. K. (2006). Specific and randomly derived immunoactive peptide mimotopes of mycobacterial antigens. Clin Vaccine Immunol 13, 1143–1154 10.1128/CVI.00127-06 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith G. P. (1985). Filamentous fusion phage: novel expression vectors that display cloned antigens on the virion surface. Science 228, 1315–1317 10.1126/science.4001944 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verstreate D. R., Creasy M. T., Caveney N. T., Baldwin C. L., Blab M. W., Winter A. J. (1982). Outer membrane proteins of Brucella abortus: isolation and characterization. Infect Immun 35, 979–989 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vizcaíno N., Cloeckaert A., Zygmunt M. S., Dubray G. (1996). Cloning, nucleotide sequence, and expression of the Brucella melitensis omp31 gene coding for an immunogenic major outer membrane protein. Infect Immun 64, 3744–3751 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu H. Y., Zhang X. L., Pan Q., Wu J. (2005). Functional selection of a type IV pili-binding peptide that specifically inhibits Salmonella Typhi adhesion to/invasion of human monocytic cells. Peptides 26, 2057–2063 10.1016/j.peptides.2005.03.035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang G., Cheng H., Liu C., Xue Y., Gao Y., Liu N., Gao B., Wang D., Li S. & other authors (2003). Inhibition of Staphylococcus aureus pathogenesis in vitro and in vivo by RAP-binding peptides. Peptides 24, 1823–1828 10.1016/j.peptides.2003.09.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yi G., Qian J., Wang Z., Qi Y. (2003). A phage-displayed peptide can inhibit infection by white spot syndrome virus of shrimp. J Gen Virol 84, 2545–2553 10.1099/vir.0.19001-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]