Abstract

Background

The intravenous administration of scopolamine produces rapid antidepressant effects. Generally, failing multiple previous antidepressant trials is associated with a poor prognosis for response to future medications. This study evaluated whether treatment history predicts antidepressant response to scopolamine.

Methods

Treatment resistant patients (2 failed medication trials) (n= 31) and treatment naïve patients (no exposure to psychotropic medication) (n=31) with recurrent major depressive or bipolar disorder participated in a double-blind, placebo-controlled, crossover clinical trial. Following a placebo lead-in, participants randomly received P/S or S/P (P= 3 placebo; S= 3 scopolamine (4ug/kg) sessions 3 to 5 days apart). The Montgomery–Asberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS) was the primary outcome measure. A linear mixed model was used to examine the interaction between clinical response and treatment history, adjusting for baseline MADRS.

Results

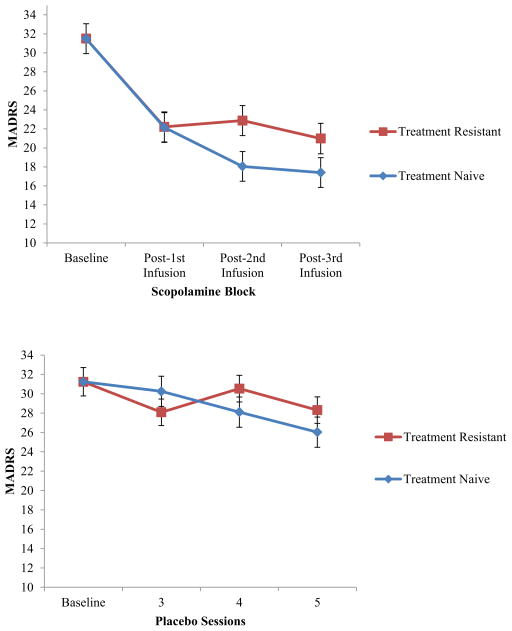

Treatment resistant and treatment naïve subjects combined responded significantly to scopolamine compared to placebo (F=15.06, p<0.001). Reduction in depressive symptoms was significant by the first post-scopolamine session (F=42.75, p< 0.001). A treatment history by scopolamine session interaction (F=3.37, p=0.04) indicated treatment naïve subjects had lower MADRS scores than treatment resistant patients; this was significant after the second scopolamine infusion (t=2.15, p=0.03).

Limitations

Post-hoc analysis. Also, we used a single regimen to administer scopolamine, and smokers were excluded from the sample, limiting generalizability.

Conclusions

Treatment naïve and treatment resistant patients showed improved clinical symptoms following scopolamine, while those who were treatment naïve showed greater improvement. Scopolamine rapidly reduces symptoms in both treatment history groups, and demonstrates sustained improvement even in treatment resistant patients.

Keywords: Treatment history, Treatment resistant, Scopolamine, Depression, Antidepressant

1. Introduction

Major depression is a severely debilitating illness that affects approximately 14.8 million American adults (Kessler et. al, 2005, US Census Bureau, 2013). Approximately 40% of patients with major depressive disorder (MDD) do not respond to the first medication trial (Sackeim, 2001). Response to a conventional antidepressant drug trial is generally not evident for 3 to 4 weeks, and multiple trials are often required to achieve treatment response, which prolongs patient discomfort and increases the risk of self-harm and harm to others (Insel and Wang, 2009). Given the need for quicker and more effective therapeutic agents, the identification of novel antidepressants that produce more rapid therapeutic effects and their predictors of response remain critical.

As a novel antidepressant, scopolamine has been shown to produce rapid and robust antidepressant effects in currently depressed unipolar (MDD) and bipolar (BD) patients (Furey and Drevets, 2006, Drevets and Furey, 2010). Scopolamine blocks cholinergic muscarinic receptors, and previous studies have shown cholinergic-muscarinic dysregulation in mood disorders (Janowsky and Overstreet, 1990). While the rate of clinical response has been relatively high (Furey and Drevets, 2006), not all patients respond to scopolamine.

The current study assessed history of treatment response as a potential predictor of response to scopolamine. Previous studies indicate failing multiple antidepressant trials is associated with a poorer prognosis for future trials (Rush et. al., 2006). For example, in the STAR*D study, third-step treatments following two traditional antidepressant trials showed modest response rates, suggesting an increased risk of failure after each subsequent failed medication trial (McGrath et. al., 2006, Nierenberg et. al., 2006). These findings indicate the identification of antidepressants that significantly reduce symptom severity in treatment resistant patients is vital to the treatment of depression. Clinical practice would also benefit from the identification of first-line antidepressants for treatment resistant depression which would significantly reduce the need for future trials.

The present analysis examined whether treatment history predicts antidepressant response to scopolamine. We hypothesized that subjects would show a significant reduction in depressive symptoms regardless of treatment history.

2. Methods

2.1 Participants

75 subjects (18–55 years of age) with Major Depressive Disorder or Bipolar Disorder were identified for inclusion in this post-hoc analysis. All recruitment and study procedures occurred at the National Institute of Mental Health, and all participants were screened in the inpatient or outpatient clinic. Eligibility was based on meeting criteria for Major Depressive Disorder or Bipolar Disorder as determined by the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition, Text Revision (DSM-IV-TR) (American Psychiatric Association, 2000). All participants were medication free for at least 2 weeks, denied current nicotine use, did not have a history of substance abuse within 5 years, or lifetime history of substance dependence, and were in a current major depressive episode without psychotic features.

Treatment history was characterized through clinician interviews which assessed medical and psychiatric history, including response to each prior medication trial. A failed medication trial was defined as a lack of therapeutic response (lifetime) after adequate duration and dosage (Fava and Davidson, 1996). Of the 75 subjects, 13 were excluded from analysis due to having a history of only one medication trial (n=7), or having a partial response to one or more previous medications (n=6). The remaining 62 subjects (MDD= 49, BP I =1, BP II = 12; mean age = 32.4, SD = 9.5) were categorized as treatment naïve if they never received medication for depression (n=31; MDD=27, BP II = 4), or as treatment resistant if they failed two or more medication trials of adequate duration (n=31; MDD=22, BP I = 1, BP II = 8). Data for 52 of the original 75 patients have been reported in previous publications (Furey and Drevets, 2006, Drevets and Furey, 2010, Furey et al., 2010).

The study was approved by the Combined Neuroscience Institutional Review Board (IRB) of the National Institutes of Health (NIH). All subjects provided written informed consent before entry into the study.

2.2 Study Design

All subjects participated in a double-blind, placebo-controlled, crossover clinical trial consisting of 7 infusion sessions and a follow up evaluation. Each session included clinician administered depression rating scales, followed by a 15 minute intravenous infusion of either placebo or scopolamine (4ug/kg). Following a placebo lead-in, participants were randomly assigned to P/S or S/P where P represents a block of 3 consecutive placebo infusion sessions, and S represents a block of 3 consecutive scopolamine infusion sessions. Each infusion was conducted 3 to 5 days apart, and a follow up evaluation was conducted approximately 3 to 5 days after the final infusion. During each session, participants completed self-report ratings, as well as clinician administered scales that included the Montgomery–Asberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS) (Khan et al., 2002) as the primary outcome measure. In cases where follow-up assessments could not be obtained after session 7, or after the final scopolamine infusion (n=4), response rate analyses were performed using the last observation carried forward (LOCF).

2.3 Statistical Analysis

Baseline MADRS was defined as the average of sessions 1 and 2 for all subjects as both ratings occurred prior to receiving drug. Baseline scores were included as a covariate in the primary analyses.

A treatment group (P or S) by session by treatment history (naïve v. resistant) factorial linear mixed model was performed on symptom severity (i.e. MADRS). Due to the crossover block design and the potential for carryover effects of receiving drug before placebo, only sessions 3 through 5 were used for drug comparisons. A first order autoregressive covariance structure with restricted maximum likelihood estimation was used. Post-hoc, Bonferroni-adjusted simple effects tests were used to characterize significant interactions identified in the overall model. Significance was defined as p< 0.05, two-tailed.

Given the potential for seeing a non-significant drug by treatment history interaction in the initial statistical model based on limited power, a treatment history by session linear mixed model was performed using only the scopolamine phases to determine whether treatment history influences the magnitude of clinical response to scopolamine specifically. A separate model included baseline as a time-point instead of as a covariate to examine changes from baseline to the first assessment post-scopolamine.

Patients were characterized as achieving (1) a full response (≥50% reduction in MADRS scores from baseline), (2) a partial response (<50% but ≥25% reduction), or (3) no response (<25% reduction), as well as achieving remission (MADRS score ≤10) by study end in addition to post-scopolamine treatment (Nierenberg and DeCecco, 2001). Chi-square tests were used to compare response and remission rates between treatment history groups.

3. Results

Demographic characteristics of the treatment history groups as well as their baseline depression severity scores (i.e. MADRS) are shown in Table 1. The treatment history groups did not differ on age (p=0.43), gender (p=0.50), baseline MADRS (p=0.26), or duration of illness (p=0.68), indicating these factors were reasonably balanced across groups.

Table 1.

Demographics, and outcome indices for patients after receiving the third infusion of scopolamine or placebo, as well as end of study remission and response rates.

| Treatment History | ||

|---|---|---|

| Treatment Naïve (n=31) | Treatment Resistant (n=31) | |

| Mean age ± SD | 31.45 ± 9.16 | 33.39 ± 9.83 |

| Gender (F) | 18 (58%) | 19 (61%) |

| Baseline MADRS ± SD | 30.55 ± 4.98 | 32.85 ± 4.39 |

| Duration of Illness (years) ± SD | 13.13 ± 10.78 | 14.13 ± 8.02 |

| Post-scopolamine | ||

| Full Response (≥50% reduction) | 13 (42%) | 10 (32%) |

| Partial Response (25%–49% reduction) | 9 (29%) | 6 (19%) |

| No Response (<25% reduction) | 9 (29%) | 15 (48%) |

| Remission (MADRS score ≤ 10) | 9 (29%) | 6 (19%) |

| Post-placebo | ||

| Full Response (≥50% reduction) | 2/14 (14%) | 0/18 (0%) |

| Partial Response (25%–49% reduction) | 3/14 (21%) | 5/18 (28%) |

| No Response (<25% reduction) | 9/14 (64%) | 13/18 (72%) |

| Remission (MADRS score ≤ 10) | 1/14 (7%) | 0/18 (0%) |

| End of study | ||

| Full Response (≥50% reduction) | 18 (58%) ** | 9 (29%) ** |

| Remission (MADRS score ≤ 10) | 13 (42%) * | 6 (19%) * |

Note: Response rates are given as number and percentage of patients. Placebo response rates include only subjects who received placebo in the first block.

trend level p< 0.10

significant p< 0.05

Consistent with previous findings (Furey and Drevets, 2006, Drevets and Furey, 2010), we found that patients responded significantly better to scopolamine compared to placebo (Drug main effect, F=15.06, df= 64.66, p<0.001). There was a non-significant interaction between drug and treatment history (F=0.80, df= 1,65, p=0.37), suggesting both treatment naïve and treatment resistant subjects have a similar response to scopolamine relative to placebo.

Examining scopolamine alone with all available data, a significant session by treatment history interaction (F=3.37, df= 2,117, p=0.04) indicated that treatment naïve subjects had lower MADRS scores over time than those who were treatment resistant; this was significant at the second post-scopolamine session (t=2.15, df= 104, p=0.03). The reduction in symptoms after the first scopolamine infusion was evident in both treatment groups, and the magnitude of response did not differ between groups at this time point (t=.03, df= 105, p= 0.98). Between the first and second scopolamine session assessments, the treatment naïve patients continued to improve (t= 3.17, p= 0.006), while treatment resistant patients did not show additional improvement (t= 0.51, p= 1.0). Although the treatment resistant subjects do not continue to improve after subsequent infusions, they show a sustained reduction of symptoms over time, thus demonstrating efficacy for both populations.

With baseline as a time point instead of as a covariate, reduction in depressive symptoms was significant by the first post-scopolamine session (F=42.75, df= 3,173, p<0.001) indicating the effect of scopolamine occurs rapidly within 3 to 5 days of administration.

By the last scopolamine infusion, 13 of 31 (42%) treatment naïve subjects achieved full response (Table 1), and 9 (29%) achieved complete remission of symptoms. In addition, 10 of 31 (32%) treatment resistant subjects experienced full response post-scopolamine, and 6 (19%) achieved remission of symptoms. The difference in remission rates between treatment history groups by the final scopolamine infusion was non-significant (p= 0.55). However, by study end, 18 of 31 (58%) treatment naïve subjects and 9 of 31 (29%) treatment resistant achieved full response, and this difference was significant (p= 0.04). In addition, 13 of 31 (42%) treatment naïve subjects and 6 of 31 (19%) treatment resistant subjects achieved remission. The difference in remission rates by study end approached significance (p= 0.09). No other comparisons approached significance (p> 0.10). Of those subjects who received placebo in the first block (n=32), 2 treatment naïve subjects achieved full response post-placebo. Additionally, between session 1 and 2 baseline assessments, 3 treatment naïve subjects had a partial response following the placebo lead-in. However, no subjects in either treatment group show a full response, and the mean for treatment naïve subjects at session 1 (30.84 ± 5.2) and session 2 (30.26 ± 6.1) does not significantly differ (p=0.56).

4. Discussion

The results of this study show that both treatment naïve and treatment resistant patients improve following a single scopolamine infusion. This improvement in depression severity occurred 3 to 5 days after the first intravenous infusion, illustrating scopolamine’s rapid and robust effects. The reduction in symptom severity continued for the treatment naïve group after the second infusion, whereas the treatment resistant patients showed no additional improvement.

The finding that treatment resistant patients show a significant improvement after a single dose of scopolamine is particularly noteworthy as patients who are treatment resistant often do not respond to subsequent medication trials. While there was no additional improvement across subsequent infusions, this reduction in symptoms was sustained over the course of additional sessions. Patients who are naïve to pharmacological treatment also show a substantial reduction in depressive symptoms after a single dose of scopolamine, thus experiencing improvement within 3 to 5 days of administration as opposed to the 4 to 5 weeks seen with traditional antidepressants.

Although both treatment history groups respond significantly to scopolamine, the magnitude of response is greater for the treatment naïve patients. One possible explanation for this difference is the level of medication needed to reach therapeutic effects. For treatment resistant patients, higher doses may be necessary to achieve the same effects due to possible altered receptor sensitivity (Maes et al., 1997). Further research is needed to determine if higher doses will aid in further reduction of symptoms for this population.

Our results have some limitations that should be acknowledged. The subject population was restricted to non-smokers due to the potential for interaction between nicotinic and muscarinic receptors, both of which are receptor systems in the cholinergic system. Therefore, the generalizability to smokers may be limited as this population was not assessed. Other limitations include possible un-blinding of subjects due to the presence of side effects, the lack of a formal instrument to assess adequacy of past failed trials, as well as the inclusion of lifetime failed trials instead of those occurring in the current depressive episode. Also, these results were obtained using a single intravenous regimen and a total of 3 infusions, thus efficacy of other routes of administration as well as feasibility of continuous administration remain empirical questions.

In summary, scopolamine’s rapid and robust antidepressant effects demonstrate its potential to significantly reduce symptom severity in a depressed population, including patients with treatment resistant depression. While treatment naïve and treatment resistant patients show improvement following scopolamine, treatment history appears to influence the magnitude of response.

Figure 1.

MADRS scores across sessions are shown for the scopolamine (A) and placebo (B) study blocks. Mean MADRS ± SE is shown for the treatment resistant (red) and treatment naïve (blue) patient groups.

Acknowledgments

Funding: Funding for this work was supported by the Intramural Research Program at the National Institute of Mental Health, National Institutes of Health (IRP-NIMH-NIH), by a NARSAD Independent Investigator Award to CAZ, and by the Brain & Behavior Mood Disorders Research Award to CAZ.

We thank the Experimental Therapeutics and Pathophysiology Branch nursing staff for subject recruitment and evaluation, David Luckenbaugh for statistical advice, and Carlos Zarate and the 5SW and 7SE Hospital staff for medical support. This research was supported by the NIH NIMH-DIRP.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest

All other authors declare they have no conflicts of interest.

Disclosures: A patent for the use of ketamine in depression has been approved listing Dr. Carlos Zarate among the inventors; a patent for the use of scopolamine in depression is pending listing Dr. Maura Furey among the inventors. Both co-authors have assigned their rights on the patent to the U.S. government, but will share a percentage of any royalties that may be received by the government.

Contributors:

Author Maura Furey designed the study and wrote the protocol. Author Jessica Ellis and David Luckenbaugh undertook the statistical analyses, and author Jessica Ellis wrote the first draft of the manuscript. All authors contributed to and have approved the final manuscript.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, IV, Text Revision. American Psychiatric Association; Washington DC: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Drevets W, Furey M. Replication of Scopolamine’s Antidepressant Efficacy: a Randomized, Placebo-Controlled Clinical Trial. Biol Psychiatry. 2010;67:432–438. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2009.11.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fava M, Davidson K. Definition and epidemiology of treatment-resistant depression. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 1996;19:179–200. doi: 10.1016/s0193-953x(05)70283-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furey M, Drevets W. Antidepressant Efficacy of the Antimuscarinic Drug Scopolamine: A Randomized, Placebo-Controlled Clinical Trial. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2006;63:1121–1129. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.63.10.1121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furey M, Khanna A, Hoffman E, Drevets W. Scopolamine Produces Larger Antidepressant and Antianxiety Effects in Women Than in Men. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2010;35:2479–2488. doi: 10.1038/npp.2010.131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Insel T, Wang P. The STAR*D trial: Revealing the need for better treatments. Psychiatr Serv. 2009;60:1466–1467. doi: 10.1176/ps.2009.60.11.1466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janowsky D, Overstreet D. Cholinergic dysfunction in depression. Pharmacol Toxicol. 1990;66:100–111. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0773.1990.tb02077.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler R, Chiu WT, Demler O, Walters EE. Prevalence, severity, and comorbidity of twelve-month DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication (NCS-R) Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62:617–627. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.6.617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khan A, Khan SR, Shankles EB, Polissar NL. Relative sensitivity of the Montgomery-Asberg Depression Rating Scale, the Hamilton Depression rating scale and the Clinical Global Impressions rating scale in antidepressant clinical trials. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 2002;17:281–285. doi: 10.1097/00004850-200211000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maes M, Bosmans E, De Jongh R, Kenis G, Vandoolaeghe E, Neels H. Increased serum IL-6 and IL-1 receptor antagonist concentrations in major depression and treatment resistant depression. Cytokine. 1997;9:853–858. doi: 10.1006/cyto.1997.0238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGrath PJ, Stewart JW, Fava M, Trivedi MH, Wisniewski SR, Nierenberg AA, Thase ME, Davis L, Biggs MM, Shores-Wilson K, Luther JF, Niederehe G, Warden D, Rush AJ. Tranylcypromine versus Venlafaxine plus Mirtazapine following three failed antidepressant medication trials for depression: A STAR*D Report. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163:1531–1541. doi: 10.1176/ajp.2006.163.9.1531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nierenberg A, DeCecco L. Definitions of antidepressant treatment response, remission, nonresponse, partial response, and other relevant outcomes: a focus on treatment-resistant depression. J Clin Psychiatry. 2001;62:5–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nierenberg AA, Fava M, Trivedi MH, Wisniewski SR, Thase ME, McGrath PJ, Alpert JE, Warden D, Luther JF, Niederehe G, Lebowitz B, Shores-Wilson K, Rush AJ. A comparison of lithium and T3 augmentation following two failed medication treatments for depression: A STAR*D report. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163:1519–1530. doi: 10.1176/ajp.2006.163.9.1519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rush AJ, Trivedi MH, Wisniewski SR, Nierenberg AA, Stewart JW, Warden D, Niederehe G, Thase ME, Lavori PW, Lebowitz BD, McGrath PJ, Rosenbaum JF, Sackheim HA, Kupfer DJ, Luther J, Fava M. Acute and longer-term outcomes in depressed outpatients requiring one or several treatment steps: a STAR*D report. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163:1905–1917. doi: 10.1176/ajp.2006.163.11.1905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sackeim H. The definition and meaning of treatment-resistant depression. J Clin Psychiatry. 2001;62:10–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- US Census Bureau. [[Accessed 05 October 2013].];US Census Bureau [ONLINE] 2013 Available at: http://www.census.gov/popest/national/asrh/