Abstract

OBJECTIVE

The purpose of this article is to describe the trends of secondary interpretations, including the total volume and format of cases.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This retrospective study involved all outside neuroradiology examinations submitted for secondary interpretation from November 2006 through December 2010. This practice utilizes consistent criteria and includes all images that cover the brain, neck, and spine. For each month, the total number of outside examinations and their format (i.e., hard-copy film, DICOM CD-ROM, or non-DICOM CD-ROM) were recorded.

RESULTS

There was no significant change in the volume of cases (1043 ± 131 cases/month; p = 0.46, two-sided Student t test). There was a significant decrease in the volume of hard-copy films submitted, with the mean number of examinations submitted per month on hard-copy film declining from 297 in 2007 to 57 in 2010 (p < 0.0001, Student t test). This decrease was mirrored by an increase in the mean number of cases submitted on CD-ROM (753 cases/month in 2007 and 1036 cases/month in 2010; p < 0.0001). Although most were submitted in DICOM format, there was almost a doubling of the volume of cases submitted on non-DICOM CD-ROM (mean number of non-DICOM CD-ROMs, nine cases/month in 2007 and 17 cases/month in 2010; p < 0.001).

CONCLUSION

There has been a significant decrease in the number of hard-copy films submitted for secondary interpretation. There has been almost a doubling of the volume of cases submitted in non-DICOM formats, which is unfortunate, given the many advantages of the internationally derived DICOM standard, including ease of archiving, standardized display, efficient review, improved interpretation, and quality of patient care.

Keywords: DICOM format, outside examination practice, secondary interpretation

The past 25 years have seen a steady transition from interpreting and archiving studies on hard-copy film to digital media. This digital transition has allowed more efficient interpretation and archiving [1, 2]. In addition to advances in computer processing and storage capabilities, this transition has also been driven by the widespread adoption of the internationally developed DICOM format [3]. DICOM provides a nonproprietary data interchange protocol, image format, and file structure that allows easier transfer of images locally from an imaging device or archive to a PACS and provides a standardized format for transfer of images to other institutions [4, 5]. Being able to efficiently gather and review a patient’s prior imaging studies can save time and health care dollars and also allows secondary interpretation, which has been shown to provide an alternative diagnosis in 7.6% of cases [6, 7].

During this transition period from hard copy to digital imaging and transfer, it is important for institutions to be able to handle outside examinations in multiple formats, including film hard copy, DICOM format on CD-ROM, and non-DICOM formats on CD-ROM. Especially in a large tertiary referral center such as ours, this need to handle multiple different formats can put a strain on personnel and space requirements and reduce productivity in a busy outside examination practice. Better understanding of these trends could help optimize resources, improve efficiencies, and produce a higher quality practice of secondary interpretation of outside examinations. This will probably become even more important with the gradual implementation of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act of 2010, including some of its desired effects such as national electronic medical records (EMRs). The purpose of this study is to document trends in the overall volume and format of outside examinations submitted for secondary interpretation.

Materials and Methods

At our tertiary care referral center, there has been a dedicated practice for secondary interpretation of outside neuroradiology examinations for over 25 years that utilizes consistent examination selection criteria. These criteria include examinations that cover the brain, face, neck, and spine and all types of modalities, including catheter angiography. The division of neuroradiology has kept detailed anonymous records on the total volume of cases submitted for secondary interpretation, as well as the examination storage format submitted. This study was performed as part of an institutional review board–exempt practice quality improvement project. This project examined the trends in volume of examinations submitted and examination format to help determine staffing needs, reading room remodeling and sizing needs, necessary light box or film changer capacity, number of electronic viewing stations and number of PCs to handle non-DICOM CD examinations.

The total number and format of all examinations submitted for secondary interpretation to the neuroradiology outside examination practice were retrospectively reviewed from November 1, 2006, through December 31, 2010. Each individual case was assigned to one of three format categories: hard-copy film, DICOM CD-ROM, or non-DICOM CD-ROM. Only examinations submitted for secondary interpretation at the request of our internal referring clinicians were included in this study. These examinations cover one or more of the following areas: the brain, face, neck, and spine. Although specific details about the modality of the examination were not recorded, these studies included the entire spectrum routinely encountered in a busy neuroradiology practice, such as MRI, CT, conventional angiography, and radiography, including myelography.

Statistical analysis was performed using a software package (JMP version 8.0, SAS Institute). Two-sided Student t tests were used where appropriate to compare trends, with a p value less than 0.05 considered statistically significant.

Results

Total Volume of Cases Submitted

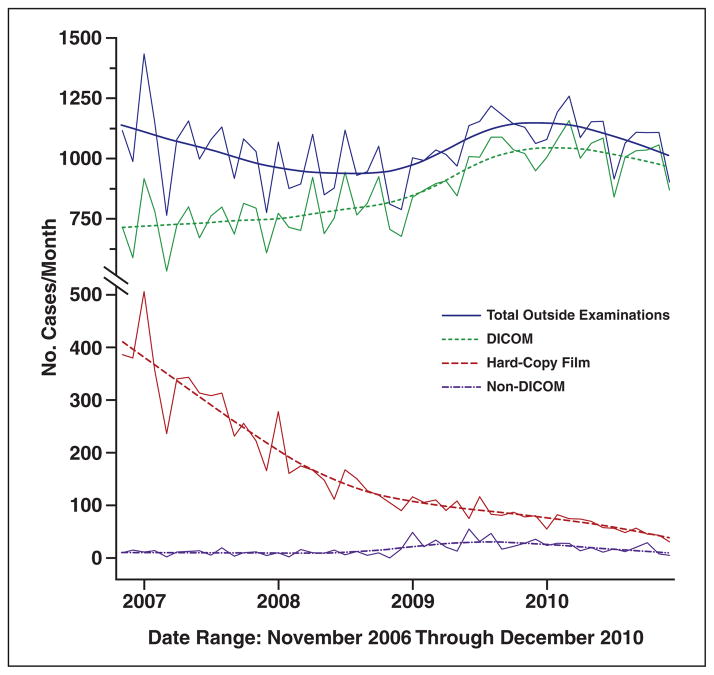

During the course of our study from November 1, 2006, through December 31, 2010, a total of 52,169 individual cases were submitted by our internal clinicians for secondary interpretation by our neuroradiology outside examination practice. Dividing the number of cases by the month in which they were submitted, a mean (± SD) of 1043 ± 131 outside examination practice cases per month was reviewed (Fig. 1). No statistically significant change in the overall volume of cases was noted during our study period (p = 0.46, two-sided Student t test).

Fig. 1.

Number of cases submitted over time divided by examination format. Graph shows stable overall number of examinations per month. There is marked decrease in number of hard-copy examinations and corresponding increase in electronically formatted CD-ROMs. Although most electronic examinations are supplied in DICOM format, there was significant increase in small percentage of non-DICOM CD-ROMs reviewed.

Transition From Hard Copy to Electronic Format via CD-ROM

As might be expected with the continued emergence of electronic examination interpretation via PACS, there was a significant decrease in the volume of hard-copy film examinations submitted for secondary interpretation. Hard-copy examinations declined from a mean of 297 cases per month in 2007 to a mean of 57 examinations per month in 2010 (p < 0.0001, two-sided Student t test). This decline in hard-copy film cases was mirrored by an increase in examinations submitted in electronic format via CD-ROM. The mean number of examinations submitted in electronic format via CD-ROM increased from 753 cases per month in 2007 to 1036 cases per month in 2010 (p < 0.0001, two-sided Student t test).

Increase in Non-DICOM CD-ROMs

Given the widespread acceptance of the DICOM format, the majority of examinations submitted electronically were submitted in the DICOM format, with a mean of 744 cases per month in 2007 and 1019 cases per month in 2010 (p < 0.0001, two-sided Student t test). That being said, without an overall increase in total case volume, there was a significant increase in the number of examinations submitted on non-DICOM CD-ROM, with the mean number of examinations submitted per month nearly doubling, from nine cases per month in 2007 to 17 cases per month in 2010 (p < 0.001 two-sided Student t test), representing an increase from 0.86% to 1.6% of total cases submitted for review.

Discussion

The benefits, in terms of both efficiency and cost, of electronic archiving and transfer of radiologic images have been clearly shown [8–10]. As a result, the past 25 years have seen a significant increase worldwide in electronic media and PACS implementation. Aided by the Integrating the Healthcare Enterprise initiative, standards for electronic communication between local and remote workstations have been strongly advocated [11]. This standardization process in radiology has been greatly aided by the introduction of the internationally developed DICOM format. However, little has been written on DICOM’s acceptance and the prevalence of its use. Our study provides some insight into this question as it pertains to the group of patients with neuroradiology examinations that are submitted for secondary interpretation at a busy tertiary care multispecialty medical center.

Although the significant reduction in hardcopy film examinations and increase in electronic format examinations will not surprise many, the trend of persistent and increasing non-DICOM format examinations may. This trend is unexplained by a change in the overall volume of examinations, because it remained relatively constant throughout our study. These non-DICOM format cases typically run via an automatic-run program to provide an imaging environment on a standard PC for viewing of the examination. However, some of these examinations may merely be JPEG screen captures of the images. Although this may be beneficial for the nonradiologist who wishes to view these cases within an office practice, the lack of DICOM formatting makes these cases very problematic to view in an efficient manner. Often the radiologist or clinician is left to view the images on a PC solely through the automatic-run programs provided by a large variety of vendors, each with unique proprietary software and image manipulation tools. In addition, this format typically does not allow side-by-side comparison of series within one examination or comparison of two different examinations or modalities. Finally, archiving of these non-DICOM cases can be difficult or impossible, which complicates referring back to these cases at a later date for treatment assessment, planning, or intervention.

Another interesting finding in our study is the static total number of cases submitted for review each month. In the current health care environment, there is increasing pressure to limit the repetition of studies performed elsewhere. In addition, there is an overall increase in the ability of institutions to share these studies electronically, limiting the effort and expense of hard-copy printing. We would have expected these two forces to increase the overall number of cases submitted for interpretation. Instead, the total number has remained stable. Although this could certainly be the result of an internal systems problem at our institution that may provide a barrier or impediment for patients bringing their outside examinations with them, we have made every attempt over the past 25 years of our outside examination practice to limit these obstacles. In fact, we have had a process in place for almost 10 years in which a patient’s radiology examination on a DICOM-compatible CD-ROM can be loaded into our DICOM-compatible institutional clinical viewer (and thereby into radiology electronic display workstations) and into EMRs from any outpatient clinical location in the Mayo Clinic Rochester campus and at selected locations within our hospital practices. Instead, we think that this more likely reflects a combination of factors, such as increasing reluctance or difficulty in patients obtaining their outside studies, increased costs incurred in copying their examinations, reduced or declined reimbursement for the reinterpretation of radiology examinations by Medicare or third-party payers, an increasing trend in radiology nationally to not interpret outside examinations unless in conjunction with a new examination performed at one’s facility, and the continued willingness by Medicare and third-party payers to reimburse for repeat radiology examinations. We expect in the future that this trend will not continue and that the overall volume of cases would increase, especially given the gradual implementation of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act of 2010, including some of its desired goals of national EMRs, reducing radiology costs, developing accountable care organizations, and affiliated care networks.

A limitation of our retrospective study is that it was confined solely to our neuroradiology outside interpretation practice. This study was designed this way intentionally because our neuroradiology outside examination practice is large, self-contained, and easily quantifiable with our current record-keeping system. Although we think that our findings could be generalized to multispecialty outside examination practices, it could be argued that the trends observed are more specific to a neuroradiology practice where certain modalities (i.e., ultrasound, PET/CT) are not represented or are underrepresented (i.e., radiography). Although we certainly acknowledge this limitation, we think that it is unlikely to significantly alter our results and conclusions. In addition, although this study focused on a large tertiary care multispecialty medical center, we think that many of the same problems are likely to exist for smaller practices. Finally, we acknowledge that the time period of this study does not allow appreciation of the entire conversion from hard-copy film cases to digital trend, but we think that it represents the most current data we have available and allows more accurate planning in the immediate future.

On the basis of our results, we have undertaken several practice changes at our institution. First, we have markedly reduced the number of hard-copy film viewers (i.e., view-boxes and film changers) within our outside examination practice. This has allowed increased efficiency by reduction in space requirement. We have not been able to entirely eliminate hard-copy viewing stations because there remains a small volume of hard-copy film. Second, we have increased the number of DICOM-compatible electronic display workstations within our practice to accommodate the trend in declining hardcopy examinations that is mirrored by an increase in DICOM formatted examinations. Unfortunately, we have also had to maintain and increase our ability to handle non-DICOM formatted examinations that cannot be viewed on our DICOM-compatible electronic display workstations. This leads to decreased efficiency of image viewing and interpretation by radiologists and clinicians, as noted previously in this article, as well as difficulty in electronic archiving of these cases for future reference and treatment assessment and planning. This trend is especially concerning given the proposed changes in healthcare reimbursement related to the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act of 2010, including accountable care organizations and affiliated care networks, the push for national EMRs, and a focus on more efficient and less redundant use of radiology imaging tests, especially high-technology digital imaging examinations (e.g., CT, MRI, ultrasound, and PET/CT).

Although from a purely technical point of view, viewing and archiving non-DICOM images may not be significantly more complex than that for DICOM images, there are several reasons why there needs to be a continued effort from the radiologic community to abandon non-DICOM images and adopt the DICOM standard. Perhaps the most significant argument for the DICOM format is from a safety standpoint. With the DICOM format, each object header contains the patient identification and examination descriptor along with the actual image, eliminating the possibility of misinterpretation resulting from mislabeling. With other non-DICOM formats, this information is not tied to the images themselves, allowing the possibility of significant error. Another argument for the DICOM format is that image resolution and quality is more reliably preserved during the transfer. Support for the full range of gray levels in medical imaging as well as appropriate compression levels is often a challenge with both JPEG file creators and viewers. In addition, from a resource point of view, non-DICOM formatted images often require a separate viewing station, which leads to increased expense for an examination that may be inferior in quality from that which was initially acquired. In fact, these same arguments have been communicated to several large regional referral centers that only provide non–DICOM-compatible examinations for their patients who visit our institution. To date, these institutions have not changed their behavior, possibly because of cost issues related to their present non-DI-COM storage methods and the added cost for converting to a DICOM system. Finally, at our institution, non-DICOM examinations cannot be stored in our DICOM-compatible institutional clinical viewer and, therefore, the EMR. This will become a problem nationally with the drive to implement EMRs, which will require standardization and, therefore, DICOM-compatible images for all specialties, including radiology.

In conclusion, we strongly recommend continuing the transition to electronic DICOM format for examination transfer between institutions. This format allows efficient transfer of images between institutions, facilitates comparison of series within a study and between different studies and modalities, and enables data storage for future comparison and thereby more efficient examination viewing and higher quality interpretations.

References

- 1.Chan L, Trambert M, Kywi A, Hartzman S. PACS in private practice: effect on profits and productivity. J Digit Imaging. 2002;15(suppl 1):131–136. doi: 10.1007/s10278-002-5019-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fleishon HB, Bhargavan M, Meghea C. Radiologists’ reading times using PACS and using films: one practice’s experience. Acad Radiol. 2006;13:453–460. doi: 10.1016/j.acra.2005.12.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lienemann B, Hodler J, Luetolf M, Pfirrmann CW. Swiss teleradiology survey: present situation and future trends. Eur Radiol. 2005;15:2157–2162. doi: 10.1007/s00330-005-2764-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bidgood WD, Jr, Horii SC, Prior FW, Van Syckle DE. Understanding and using DICOM, the data interchange standard for biomedical imaging. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 1997;4:199–212. doi: 10.1136/jamia.1997.0040199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hynes DM, Stevenson G, Nahmias C. Towards filmless and distance radiology. Lancet. 1997;350:657–660. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(97)08157-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yousem DM. Establishing an outside film reading service/dealing with turf issues: unintended consequences. J Am Coll Radiol. 2010;7:480–481. doi: 10.1016/j.jacr.2009.11.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zan E, Yousem DM, Carone M, Lewin JS. Second-opinion consultations in neuroradiology. Radiology. 2010;255:135–141. doi: 10.1148/radiol.09090831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Berlin L. Storage and release of radiographs. AJR. 1997;168:895–897. doi: 10.2214/ajr.168.4.9124135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Langlotz CP, Even-Shoshan O, Seshadri SS, et al. A methodology for the economic assessment of picture archiving and communication systems. J Digit Imaging. 1995;8:95–102. doi: 10.1007/BF03168132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Straub WH, Gur D. The hidden costs of delayed access to diagnostic imaging information: impact on PACS implementation. AJR. 1990;155:613–616. doi: 10.2214/ajr.155.3.2117364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dreyer KJ. Why IHE? RadioGraphics. 2000;20:1583–1584. doi: 10.1148/radiographics.20.6.g00no381583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]