Summary

Mutations in the gene encoding the gap junction protein connexin26 (Cx26) are responsible for the autosomal recessive isolated deafness, DFNB1, which accounts for half of the cases of prelingual profound hereditary deafness in Caucasian populations [1–5]. To date, in vivo approaches to decipher the role of Cx26 in the inner ear have been hampered by the embryonic lethality of the Cx26 knockout mice [6]. To overcome this difficulty, we performed targeted ablation of Cx26 specifically in one of the two cellular networks that it underlies in the inner ear, namely, the epithelial network. We show that homozygous mutant mice, Cx26OtogCre, have hearing impairment, but no vestibular dysfunction. The inner ear developed normally. However, on postnatal day 14 (P14), i.e., soon after the onset of hearing, cell death appeared and eventually extended to the cochlear epithelial network and sensory hair cells. Cell death initially affected only the supporting cells of the genuine sensory cell (inner hair cell, IHC), thus suggesting that it could be triggered by the IHC response to sound stimulation. Altogether, our results demonstrate that the Cx26-containing epithelial gap junction network is essential for cochlear function and cell survival. We conclude that prevention of cell death in the sensory epithelium is essential for any attempt to restore the auditory function in DFNB1 patients.

Results and Discussion

Generation of Cx26-Deficient Mice in the Epithelial Gap Junction Network of the Inner Ear

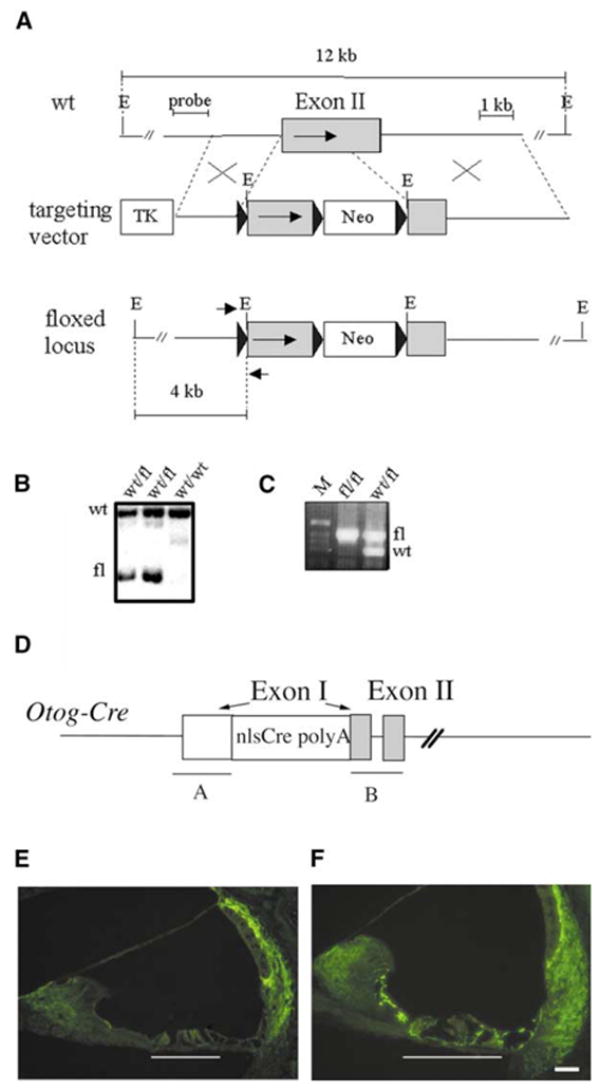

In the inner ear, gap junctions assemble into two independent cellular networks, i.e., the epithelial and connective tissue gap junction networks [7, 8] (see Figure 1). Cx26 seems to be present in all gap junctions of both networks [7, 8]. To specifically inactivate Cx26 in the epithelial gap junction network of the inner ear, which is composed of supporting cells of the sensory hair cells and flanking epithelial cells, we generated two recombinant mouse lines (Figure 2). Cx26loxP/loxP mice were obtained by homologous recombination in embryonic stem (ES) cells. In these mice, the Cx26 coding exon (exon II) and the neo selection marker are flanked by loxP sites (Figures 2A–2C). The Otog-Cre mouse line was obtained by transgenesis using a recombinant bacterial artificial chromosome (BAC) containing the Cre gene under the control of the murine Otog promoter. Otog is exclusively transcribed in the inner ear [9]. Otog expression is detected as early as embryonic day 10 (E10) in the otic vesicle and at E18 in all cells of the gap junction epithelial network [10].

Figure 1. Schematic Representation of a Transverse Section of the Cochlear Duct.

The cochlear duct is filled with a K+-rich liquid, the endolymph (in yellow), and is immersed in a Na+-rich liquid, the perilymph (in blue). The endolymphatic compartment and the intrastrial compartment are delimited by a tight junction network (red line). The organ of Corti, the cochlear sensory epithelium, lies on the basilar membrane (bm). The cochlear epithelial gap junction network appears by embryonic day 16 (E16) and comprises interdental cells (i), inner sulcus cells (is), Claudius cells (c), outer sulcus cells (os), and root cells (r) (all in pink). It also comprises supporting cells of the organ of Corti (all in blue), which include border cells (b), inner phalangeal cells (ip), inner and outer pillar cells (p), Deiters’ cells (d), and Hensen’s cells (h), but not the sensory hair cells [7, 8, 33]. The cochlear connective tissue gap junction network begins to develop at birth and comprises fibrocytes (f) of the spiral ligament (slg) and spiral limbus (sl), mesenchymal cells lining the scala vestibuli (m), and the basal and intermediate cells (but not the marginal cells) of the stria vascularis (sv) (in green) [7, 8, 34]. The stria vascularis is a bilayered epithelium, which secretes the K+ into the endolymph [35], and is responsible for the generation of the endocochlear potential [36]. rm, Reissner’s membrane; ohc, outer hair cells; ihc, inner hair cells; tm, tectorial membrane; cn, cochlear nerve; sp, spiral prominence.

Figure 2. Generation of Mice Deficient for Cx26 in the Epithelial Gap Junction Network of the Inner Ear.

(A–C) Generation of Cx26loxP/loxP mice. (A) Structure of the wild-type Cx26 allele, the gene targeting vector, and the floxed allele (from the top to the bottom). The coding region of Cx26 exon II is marked by an arrow. Black triangles represent the loxP sites. The probe used for the Southern blot analysis and the EcoRI (E) restriction fragments detected with this probe (12 kb and 4 kb) are indicated. Small arrows mark the positions of the PCR primers, Cx26R and Cx26F, used for genotyping. TK, thymidine kinase selection cassette; Neo, neomycin-resistance selection cassette. (B) Southern blot analysis of properly targeted ES cell clones. Wild-type (wt) and mutated (fl) restriction fragments are indicated. (C) Genotyping of mice by PCR amplification. M, DNA size ladder.

(D) Structure of the Otog-Cre transgene. Cre was inserted into a BAC containing Otog by homologous recombination. polyA, bovine growth hormone polyadenylation signal; nls, nuclear localization signal. The white box represents the 5′-untranslated region of Otog exon 1 (left arrow). Gray boxes represent the coding sequences of Otog exons 1 (right arrow) and 2. “A” and “B” indicate the sequences used for homologous recombination in the original BAC.

(E and F) Immunohistofluorescence analysis of Cx26 distribution at P15 on transverse sections of the cochlear duct. White lines indicate the position of the organ of Corti. (E) Cx26OtogCre mice. (F) Cx26loxP/loxP mice. In Cx26OtogCre mice, Cx26 is no longer expressed in the supporting cells of the organ of Corti or in the flanking epithelial cells. In contrast, Cx26 is still expressed by the fibrocytes of the spiral limbus and spiral ligament, as well as by the basal and intermediate cells of the stria vascularis. The scale bars in (E) and (F) represent 40 μm.

Cx26loxP/loxP and Otog-Cre mice were both viable and had no hearing loss, and the distribution of Cx26 in the inner ear was identical to that of wild-type mice (see Figure 2F). Otog-Cre mice were crossed with Cx26loxP/loxP mice. In Cx26loxP/loxPOtogCre (abbreviated Cx26OtogCre) double transgenic mice, from birth onward, Cx26 was detected neither in the sensory epithelium nor in adjacent epithelial cells of the cochlea (see Figure 2E) and the vestibular end organs (data not shown). In contrast, Cx26 labeling in the fibrocytes and the stria vascularis basal cell layer was similar to that of wild-type mice (Figures 2E and 2F). No modification in the expression pattern of connexin30 (Cx30), another gap junction protein that normally colocalizes with Cx26 in the inner ear [11], could be detected in Cx26OtogCre mice (data not shown).

Phenotypic Analysis of Cx26OtogCre Mice

We examined inner ear function, i.e., balance and audition of 3- to 12-week-old mice: Cx26OtogCre (n = 41), heterozygous (Cx26loxP/+OtogCre) (n = 17), and control (Cx26loxP/loxP) mice (n = 52). In Cx26OtogCre mice, vestibular tests failed to reveal any balance dysfunction. To test audition, auditory brainstem responses (ABR) were recorded from the two ears upon a broad-band click stimulus covering sound frequencies from 2 to 20 kHz and pure tone pips at 8, 16, and 32 kHz (see Figure S1 in the Supplementary Material available with this article online). Similar hearing thresholds were measured in heterozygous and control mice. In contrast, Cx26OtogCre mice showed a significant hearing loss, compared to heterozygous and control mice, for all frequencies tested (p < 0.0001) (see Figure S1); it ranged from 30 dB to more than 70 dB, with an average of 30 dB at 8 kHz, 31 dB at 16 kHz, and 36 dB at 32 kHz. Only 4 inner ears out of 41 had a hearing threshold > 100 dB sound pressure level (SPL). Analysis of mutant mice individually showed that the hearing loss was more pronounced at 32 kHz than at 8 kHz (p < 0.0001) (see Figure S1). These results thus establish that the Cx26 in the epithelial gap junction network has a crucial role for the auditory function.

Histological Analysis of Cx26OtogCre Cochlea

Histological analysis of the inner ear showed that, up to P14, the Cx26OtogCre cochlea was indistinguishable from that of control and heterozygous mice (Figures 3A and 3B), thus indicating that Cx26-containing epithelial gap junctions are dispensable up to the late maturation of the organ of Corti. In contrast, from P15–P16 onward, the organ of Corti tended to collapse (Figure 3D), and many epithelial cells had an altered shape (Figure 3D). A collapse of the tunnel of Corti (between pillar cells) was also observed (data not shown). Several cells, i.e., the supporting cells of OHCs and OHCs themselves (mainly from the two most internal of their three rows) were damaged or lost (Figures 3D, 4B, and 4C). The OHCs are considered to be the cochlear amplifier of the sound stimulus (reviewed in [12]). Electron microscopy analysis of the organ of Corti showed that the reticular lamina, i.e., a thick net-like plate at the apical surface of the sensory epithelium formed by the tight junctions between the hair cells and their supporting cells, was disrupted (Figures 4B and 4C). The damage of the reticular lamina is likely due to the degeneration of hair cell-supporting cells in addition to the death of OHCs. Indeed, when only OHCs died, as is often observed after aminoglycoside treatment or noise trauma, their supporting cells were able to preserve the integrity of the reticular lamina [13, 14]. At P60, some interdental cells of the spiral limbus were also missing (data not shown). In contrast, with the exception of profoundly deaf mice, the IHCs were preserved in adult mutants. However, ultrastructural analysis revealed two anomalies in the IHC synaptic area. First, several synaptic ribbons, instead of the usual single one, were frequently observed at the active zone (Figure S2A). Second, direct efferent synapses were present on these cells (Figure S2B). Both features are found in normal immature IHCs [15, 16]. Whether these anomalies are related to an interruption of development of afferent synapses or reflect an adaptative process to the damage of the organ of Corti remains to be clarified. Finally, in contrast to these alterations of the organ of Corti, the sensory epithelia of the vestibular end organs, which were analyzed up to P60, were morphologically normal (data not shown).

Figure 3. Histological Analysis of the Cochlear Structure in Cx26OtogCre Mice.

(A–D) Longitudinal sections of the cochlea and details of the organ of Corti in two Cx26OtogCre homozygous mutants at (A and B) P12 and at (C and D) P33. The structure of the organ of Corti at P12 is normal. The number and shape of the cells are normal. The arrows show the three rows of OHCs and Deiters’ cells. The arrowhead indicates the IHC. (D) In contrast, the organ of Corti of a Cx26OtogCre mutant at P33 (auditory threshold value: 75 dB at 8 kHz and 16 kHz, and 85 dB at 32 kHz) shows signs of degeneration: arrows indicate the normal emplacement of the three rows of OHCs and Deiters’ cells in which some cells of both types are now missing compared to P12. The IHC is conserved in this mutant (arrowhead). (C) The Reissner’s membrane remains well positioned. The scale bars in (A) and (C) represent 200 μm, and the scale bars in (B) and (D) represent 20 μm.

Figure 4. Electron Microscopy of the Organ of Corti in Cx26OtogCre Cochlea.

(A–C) Transmission electron microscopy at P30. (A) OHC in a heterozygous mouse with normal tight junctions on both sides of the cell. Note the presence of the dense cuticular plate at the base of the stereocilia. (B and C) Degenerated OHCs and Deiters’ cells (D) in a Cx26OtogCre cochlea. Note the vacuolization of the cytoplasm and the absence of a cuticular plate and stereocilia in the OHC in (B) and in the left OHC in (C). (B and C) The processes of Deiters’ cells are damaged and no longer stick to the OHCs, thus resulting in the disruption of the reticular lamina at several emplacements indicated by arrows. P, outer pillar cell. The scale bars represent 2.3 μm in (A), 1.25 μm in (B), and 0.8 μm in (C).

Endocochlear Potential and Endolymphatic Potassium Concentration Measurements

The endocochlear potential (EP), which represents the transepithelial electric potential difference between the endolymphatic and perilymphatic compartments of the cochlea, has a major contribution to the remarkable sensitivity of the auditory sensory cells. The EP is generated in the stria vascularis. It develops from P5 to P6 and reaches adult values by P17–P18 [17]. Maintenance of both the EP and the high endolymphatic K+ concentration depends on the integrity of the reticular lamina, which prevents ionic exchanges between endolymph and perilymph. EP values at P12–P13, i.e., before any damage occurs to the organ of Corti, were similar in homozygous mutants (56 ± 12 mV) and control (58 ± 12 mV) mice (Figure S3). These data thus show that the Cx26-containing epithelial gap junction network is not necessary for the development of the EP, at least up to P14. In contrast, adult Cx26OtogCre mice had a significantly decreased EP (38 ± 14 mV) compared to control mice (110 ± 12 mV) (p < 0.001). The endolymphatic K+ concentration was also significantly lower in adult mutant mice (85 ± 21 mM) compared to control mice (153 ± 7 mM) (p < 0.001). The decrease of these two parameters, since they are concomitant to the appearance of morphological anomalies in the organ of Corti (from P15 to P16), likely results from the disruption of the reticular lamina. Consistently, no collapse of the Reissner’s membrane was observed in the mutants (see Figure 3C). Finally, although Cx26OtogCre adult mice still possess sensory cells, no negative EP was recorded under anoxia, thus substantiating the loss of integrity of the reticular lamina (data not shown) [18].

Detection of Cell Death in the Cx26OtogCre Cochlea

To monitor the process of cell death within the cochlea, we performed TUNEL experiments during postnatal development of the Cx26OtogCre. Labeled cells were counted and identified, i.e., hair cells versus supporting cells, using a myosin VIIA antibody that exclusively labels the hair cells [19, 20] (Figure 5 and Table S1 in the Supplementary Material). The first difference between Cx26OtogCre and control or heterozygous mice was seen at P14 (Table S1). From this stage onward, no cell death was detected in the cochlear neuroepithelium of both control and heterozygous mice (Table S1). By contrast, in Cx26OtogCre mice, the two supporting cells flanking the IHC, namely, the border cell and the inner phalangeal cell, displayed TUNEL labeling (Figure 5A). No other cells were labeled at this stage. From P16 onward, the labeling extended to other cell types in the organ of Corti, i.e., to OHCs and their supporting cells (Deiters’ and Hensen’s cells) (Figures 5B and 5C and Table S1), as well as to the Claudius cells and outer sulcus cells. At P30, TUNEL labeling was limited to OHCs (Table S1). At P60, some interdental cells were labeled (Figure 5D). Cell death was not detected, at any stage, either in the neurons of the cochlear ganglion that mainly innervate the IHCs, in the fibrocytes of the spiral limbus and spiral ligament, or in the stria vascularis. Finally, using immunofluorescent detection of activated caspase 3 on tissue sections, we identified apoptosis as the mechanism underlying the cell death observed in Cx26OtogCre mice (Figure 5B).

Figure 5. Detection of Dying Cells by TUNEL and Activated Caspase 3 Immunodetection in Cx26OtogCre Cochlea.

(A–D) Four sections of the organ of Corti in Cx26OtogCre mice at P14, P16, P30, and P60. Myosin VIIA immunofluorescent staining of the hair cells (in red) was performed prior to the TUNEL reaction (in green). White arrows indicate dying cells, namely, an IHC-supporting cell (border cell) in (A), an OHC-supporting cell in (B), an OHC in (C), and an interdental cell in (D). Note the normal structure of the organ of Corti at P14 compared to P16. The picture framed in (B) shows the immunofluorescent detection of the activated form of caspase 3 in a Cx26OtogCre section of the organ of Corti at P17. Punctiform labeling is detected in the three rows of Deiters’ cells. The arrowheads indicate the hair cell emplacements. The scale bars represent 10 μm in (A)–(C) and 40 μm in (D).

Cell death of the IHC-supporting cells is thus the first detectable anomaly in the Cx26OtogCre mice. It occurs at P14, at the onset of hearing, while the endolymphatic potential rises. This strongly suggests that the activity of IHCs triggers the death of the IHC-supporting cells. Upon sound stimulation, the IHC releases K+ and the neurotransmitter glutamate [21] into the perilymph that bathes its basolateral membrane. It has been proposed that K+ could be taken up by the supporting cells flanking the hair cells and then funneled through the epithelial gap junction system [22–24] (see Figure 1). In the context of this hypothesis, we propose that a local, but significant, increase of the extracellular K+ concentration could occur as a result of the absence of Cx26. Elevation of the extracellular K+ concentration is expected to have a direct influence on the functioning of the glutamate transporter GLAST, which is highly expressed in the IHC-supporting cells and plays a key role in the removal of glutamate from the extracellular fluid [25, 26]. In such an environment, this transporter could function in a reverse mode [27], leading to an extracellular accumulation of glutamate, which has been reported to have an inhibitory effect on the synthesis of the antioxidant glutathione [28–30]. Local extracellular accumulation of K+ ions could therefore result in the death of the IHC-supporting cells by oxidative stress.

In conclusion, our results demonstrate that Cx26-containing epithelial gap junctions are not required for the functioning of the vestibular apparatus. In contrast, they are necessary for cochlear functioning. The deafness observed in mutant mice is related to the cell death within the organ of Corti, which starts at P14, i.e., soon after the onset of hearing. Among the histopathological anomalies observed, two are expected to contribute to the 30–36 dB hearing loss generally observed in mutant mice, namely, the frequent loss of OHCs and the low EP. Indeed, OHC plays a crucial role in the exquisite sensitivity of the cochlea [31]. Besides, low EP should decrease the driving force for K+ influx through hair cell transducer channels [32]. Finally, our results suggest that the first requirement for restoring the auditory function or halting the progression of hearing loss observed in some DFNB1-affected patients is to block the apoptotic process using therapeutic strategies that can now be tested using the animal model described here.

Acknowledgments

We thank J. Levilliers, S. Cure, and S. Safieddine for critical reading of the manuscript and M. Lenoir and J.-L. Puel for helpful discussions. We are grateful to V. Guyot for technical help in transgenesis, C. Elbaz, M.-C. Simmler, and M. Huerre for technical help in histological analysis, N. Renard and F. Tribillac for help in electron microscopy, P. Roux for help in confocal microcopy, and N. Da Silva for help with statistical analysis. This work was supported by Association Française contre les Myopathies, the European Community, Fondation pour la Recherche Médicale, the National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders, the Fritz Thyssen Foundation, and Fonds der Chemischen Industrie.

Footnotes

Supplementary Material

Supplementary material including Experimental Procedures, Table S1, and Figures S1–S3 can be found at http://images.cellpress.com/supmat/supmatin.htm.

References

- 1.Kelsell DP, Dunlop J, Stevens HP, Lench NJ, Liang JN, Parry G, Mueller RF, Leigh IM. Connexin 26 mutations in hereditary non-syndromic sensorineural deafness. Nature. 1997;387:80–83. doi: 10.1038/387080a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Denoyelle F, Weil D, Maw MA, Wilcox SA, Lench NJ, Allen-Powell DR, Osborn AH, Dahl HHM, Middleton A, Houseman MJ, et al. Prelingual deafness: high prevalence of a 30delG mutation in the connexin 26 gene. Hum Mol Genet. 1997;6:2173–2177. doi: 10.1093/hmg/6.12.2173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zelante L, Gasparini P, Estivill X, Melchionda S, D’Agruma L, Govea N, Mila M, Della Monica M, Lutfi J, Shohat M, et al. Connexin26 mutations associated with the most common form of non-syndromic neurosensory autosomal recessive deafness (DFNB1) in Mediterraneans. Hum Mol Genet. 1997;6:1605–1609. doi: 10.1093/hmg/6.9.1605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rabionet R, Gasparini P, Estivill X. Molecular genetics of hearing impairment due to mutations in gap junction genes encoding β-connexins. Hum Mutat. 2000;16:190–202. doi: 10.1002/1098-1004(200009)16:3<190::AID-HUMU2>3.0.CO;2-I. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Petit C, Levilliers J, Hardelin JP. Molecular genetics of hearing loss. Annu Rev Genet. 2001;35:859–865. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genet.35.102401.091224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gabriel HD, Jung D, Butzler C, Temme A, Traub O, Winterhager E, Willecke K. Transplacental uptake of glucose is decreased in embryonic lethal connexin26-deficient mice. J Cell Biol. 1998;140:1453–1461. doi: 10.1083/jcb.140.6.1453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kikuchi T, Adams LC, Paul DL, Kimura RS. Gap junction systems in the rat vestibular labyrinth: immunohistochemical and ultrastructural analysis. Acta Otolaryngol. 1994;114:520–528. doi: 10.3109/00016489409126097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kikuchi T, Kimura RS, Paul DL, Adams JC. Gap junctions in the rat cochlea: immunohistochemical and ultrastructural analysis. Anat Embryol. 1995;191:101–118. doi: 10.1007/BF00186783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cohen-Salmon M, El-Amraoui A, Leibovici M, Petit C. Otogelin: a glycoprotein specific to the acellular membranes of the inner ear. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:14450–14455. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.26.14450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.El-Amraoui A, Cohen-Salmon M, Petit C, Simmler MC. Spatiotemporal expression of otogelin in the developing and adult mouse inner ear. Hear Res. 2001;158:151–159. doi: 10.1016/s0378-5955(01)00312-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lautermann J, ten Cate WJ, Altenhoff P, Grummer R, Traub O, Frank H, Jahnke K, Winterhager E. Expression of the gap-junction connexins 26 and 30 in the rat cochlea. Cell Tissue Res. 1998;294:415–420. doi: 10.1007/s004410051192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dallos P. The active cochlea. J Neurosci. 1992;12:4575–4585. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.12-12-04575.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Forge A. Outer hair cell loss and supporting cell expansion following chronic gentamicin treatment. Hear Res. 1985;19:171–182. doi: 10.1016/0378-5955(85)90121-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Leonova EV, Raphael Y. Organization of cell junctions and cytoskeleton in the reticular lamina in normal and ototoxically damaged organ of Corti. Hear Res. 1997;113:14–28. doi: 10.1016/s0378-5955(97)00130-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pujol R, Carlier E, Lenoir M. Ontogenetic approach to inner and outer hair cells functions. Hear Res. 1980;2:423–430. doi: 10.1016/0378-5955(80)90078-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Glowatzki E, Fuchs PA. Cholinergic synaptic inhibition of inner hair cells in the neonatal mammalian cochlea. Science. 2000;288:2366–2368. doi: 10.1126/science.288.5475.2366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sadanaga M, Morimitsu T. Development of endocochlear potential and its negative component in mouse cochlea. Hear Res. 1995;89:155–161. doi: 10.1016/0378-5955(95)00133-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Komune S, Ide M, Nakano T, Morimitsu T. Effects of kanamycin sulfate on cochlear potentials and potassium ion permeability through the cochlear partitions. ORL J Otorhinolaryngol Relat Spec. 1987;49:9–16. doi: 10.1159/000275900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.El-Amraoui A, Sahly I, Picaud S, Sahel J, Abitbol M, Petit C. Human Usher IB/mouse shaker-1; the retinal phenotype discrepancy explained by the presence/absence of myosin VIIA in the photoreceptor cells. Hum Mol Genet. 1996;5:1171–1178. doi: 10.1093/hmg/5.8.1171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hasson T, Gillespie PG, Garcia JA, MacDonald RB, Zhao Y, Yee AG, Mooseker MS, Corey DP. Unconventional myosins in inner-ear sensory epithelia. J Cell Biol. 1997;137:1287–1307. doi: 10.1083/jcb.137.6.1287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Eybalin M. Neurotransmitters and neuromodulators of the mammalian cochlea. Physiol Rev. 1993;73:309–373. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1993.73.2.309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Oesterle EC, Dallos P. Intracellular recordings from supporting cells in the guinea pig cochlea: DC potentials. J Neurophysiol. 1990;64:617–636. doi: 10.1152/jn.1990.64.2.617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Santos-Sacchi J, Huang GJ, Wu M. Mapping the distribution of outer hair cell voltage-dependent conductances by electrical amputation. Biophys J. 1997;73:1424–1429. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(97)78174-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Spicer SS, Schulte BA. Evidence for a medial K+ recycling pathway from inner hair cells. Hear Res. 1998;118:1–12. doi: 10.1016/s0378-5955(98)00006-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Furness DN, Lehre KP. Immunocytochemical localization of a high-affinity glutamate-aspartate transporter, GLAST, in the rat and guinea pig cochlea. Eur J Neurosci. 1997;9:1961–1969. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.1997.tb00763.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hakuba N, Koga K, Gyo K, Usami S-i, Tanaka K. Exacerbation of noise-induced hearing loss in mice lacking the glutamate transporter GLAST. J Neurosci. 2000;20:8750–8753. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-23-08750.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Szatkowski M, Barbour B, Attwell D. Non-vesicular release of glutamate from glial cells by reversed electrogenic glutamate uptake. Nature. 1990;348:443–446. doi: 10.1038/348443a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Murphy TH, Miyamoto M, Sastre A, Schnaar RL, Coyle JT. Glutamate toxicity in a neuronal cell line involves inhibition of cystine transport leading to oxidative stress. Neuron. 1989;2:1547–1558. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(89)90043-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tan S, Wood M, Maher P. Oxidative stress induces a form of programmed cell death with characteristics of both apoptosis and necrosis in neuronal cells. J Neurochem. 1998;71:95–105. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1998.71010095.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tan S, Sagara Y, Liu Y, Maher P, Schubert D. The regulation of reactive oxygen species production during programmed cell death. J Cell Biol. 1998;141:1423–1432. doi: 10.1083/jcb.141.6.1423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ryan A, Dallos P. Effect of absence of cochlear outer hair cells on behavioral auditory threshold. Nature. 1975;253:44–45. doi: 10.1038/253044a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dallos P. Overview: cochlear neurobiology. In: Fay RF, Popper AN, editors. The Cochlea. New York: Springer; 1996. pp. 1–43. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Frenz CM, Van De Water T. Immunolocalization of connexin26 in the developing mouse cochlea. Brain Res Rev. 2000;32:172–180. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0173(99)00078-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Xia AP, Kikuchi T, Hozawa K, Katori Y, Takasaka T. Expression of connexin26 and Na,K-ATPase in the developing mouse cochlear lateral wall: functional implications. Brain Res. 1999;846:106–111. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(99)01996-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wangemann P, Liu J, Marcus DC. Ion transport mechanisms responsible for K+ secretion and the transepithelial voltage across marginal cells of stria vascularis in vitro. Hear Res. 1995;84:19–29. doi: 10.1016/0378-5955(95)00009-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tasaki I, Spyropoulos CS. Stria vascularis as source of endocochlear potential. J Neurophysiol. 1959;22:149–155. doi: 10.1152/jn.1959.22.2.149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]