Abstract

Angiotensin (Ang)-(1-7), an endogenous ligand for the G protein-coupled receptor Mas, exerts both vasodilatory and insulin sensitizing effects. In skeletal muscle relaxation of pre-capillary arterioles recruits microvasculature and increases the endothelial surface area available for nutrient and hormone exchanges.

To assess whether Ang-(1-7) recruits microvasculature and enhances insulin action in muscle, overnight-fasted adult rats received an intravenous infusion of Ang-(1-7) (0, 10 or 100 ng/kg/min) for 150 min with or without a simultaneous infusion of the Mas inhibitor A-779 and a superimposition of a euglycemic insulin clamp (3 mU/kg/min) from 30 to 150 min. Hindlimb muscle microvascular blood volume (MBV), microvascular flow velocity (MFV) and microvascular blood flow (MBF) were determined. Myographic changes in tension were measured on pre-constricted distal saphenous artery.

Ang-(1-7) dose-dependently relaxed the saphenous artery (p<0.05) ex vivo. This effect was potentiated by insulin (p<0.01) and abolished by either endothelium denudement or Mas inhibition. Systemic infusion of Ang-(1-7) rapidly increased muscle MBV and MBF (p<0.05, each) without altering MFV. Insulin infusion alone increased muscle MBV by 60–70% (p<0.05). Adding insulin to the Ang-(1-7) infusion further increased muscle MBV and MBF (~2.5 fold, p<0.01). These were associated with a significant increase in insulin-mediated glucose disposal and muscle Akt and ERK1/2 phosphorylation. A-779 pre-treatment blunted Ang-(1-7)’s microvascular and insulin-sensitizing effects.

We conclude that Ang-(1-7) by activating Mas recruits muscle microvasculature and enhances insulin’s metabolic action. These effects may contribute to the cardiovascular protective responses associated with Mas activation and explain Ang-(1-7)’s insulin sensitizing action.

Keywords: Angiotensin, muscle, microvasculature, endothelial cell, insulin action

INTRODUCTION

Muscle accounts for 70–80% of insulin-stimulated whole body glucose disposal during insulin infusion. A rate-limiting step in muscle insulin action is the delivery of insulin to the muscle interstitium which contributes up to 40% of insulin’s metabolic action 1. This process is critically regulated by the skeletal muscle microvasculature which not only regulates the delivery of nutrients and insulin to the muscle microcirculation but also provides the endothelial surface area for their exchanges between plasma and muscle interstitium 2–4. Insulin also actively regulates its own delivery in muscle by increasing muscle microvascular blood volume (MBV) and stimulating its own trans-endothelial transport 4.

The renin-angiotensin system (RAS) critically regulates vascular tone, tissue perfusion and water balance. Angiotensin (Ang) II, the main RAS component, exerts a potent vasoconstrictive action via its type 1 receptors (AT1R) but also a vasodilatory effect via its type 2 receptors (AT2R) 5, 6. In addition, the RAS actively regulates insulin action 7–9. Prior evidence mainly focused on the antagonistic action of Ang II on insulin action via AT1R-mediated NADPH oxidase/oxidative stress pathway 10, 11 and we have recently demonstrated that Ang II also regulates insulin action via its effects on muscle microvascular perfusion. While basal AT1R activity restricts muscle microvascular perfusion and decreases muscle insulin delivery and action, AT2R activation potently recruits muscle microvasculature and rescues insulin action during systemic lipid infusion via increased insulin delivery in rodents 12–14. In mildly hypertensive humans acute AT1R blockade with irbesartan increases insulin-induced skin microvascular perfusion 15. Interestingly in healthy humans Ang II has been shown to enhance insulin-stimulated whole body glucose disposal but impair insulin-induced skin capillary recruitment 16.

In addition to AT2R, an important RAS pathway poised to oppose AT1R is the Ang-(1-7) – Ang converting enzyme-2 (ACE-2) – Mas receptor (Mas) hormonal cascade. Ang-(1-7) is a heptapeptide generated primarily from Ang II by the actions of ACE-2. Similar to Ang II’s action on the AT2R, Ang-(1-7) exerts potent vasodilatory actions on conduit arteries and microvessels via a nitric oxide (NO)-dependent mechanism 17, 18. Recent evidence suggests that in addition to its vasodilatory action Ang-(1-7) also reduces Ang II- or fructose-induced insulin resistance 19–21. Transgenic rats that express an Ang-(1-7)-releasing fusion protein have elevated circulating Ang-(1-7) levels with improved glucose tolerance and insulin-stimulated glucose uptake 22. This action does not appear to be mediated via either AT1R or AT2R. Rather, Ang-(1-7) acts on a unique G-protein coupled receptor Mas 23, 24 which is encoded by the Mas proto-oncogene and expressed constitutively in endothelial cells 25. Murine Mas-deficient aortae lose their Ang-(1-7)-induced relaxation response 23. Similarly, Ang-(1-7)-mediated relaxation of wild-type mesenteric arteries is equally impaired in both wild-type arteries pretreated with Mas inhibitor A-779 and arteries isolated from Mas-deficient mice 26. However, the mechanisms underlying Ang-(1-7)’s insulin sensitization remain unknown.

Given the critical role that microvasculature plays in regulating muscle insulin action and that Ang-(1-7) has been demonstrated to exert both vasodilatory and insulin-sensitizing actions, it is possible that Ang-(1-7) exerts its insulin sensitizing action via regulating muscle microvascular endothelial surface area. This was examined in the current study and our results indicate that Ang-(1-7) potently recruits muscle microvasculature and increases insulin-stimulated whole body glucose disposal via a Mas-dependent mechanism.

METHODS

Animal Preparations and Experimental Protocols

Overnight-fasted adult male Sprague-Dawley rats (Charles River Laboratories, Wilmington, MA) weighing 250–380 g were studied under one of the 3 protocols (Figure 1). Prior to the study rats were fed standard laboratory chow and water ad libitum and housed at 22 ± 2°C on a 12 hr light-dark cycle. Rats were anesthetized with pentobarbital sodium (50 mg/kg i.p.; Abbott Laboratories, North Chicago, IL), placed in a supine position on a heating pad to ensure euthermia and intubated to maintain a patent airway. The carotid artery and the jugular vein were cannulated with polyethylene tubing (PE-50, Fisher Scientific, Newark, DE) for arterial blood pressure monitoring, arterial blood sampling and various infusions.

Figure 1.

Experimental protocols. Protocol 1 examines Ang-(1-7)’s effects on muscle microvasculature. Protocol 2 studies whether Ang-(1-7) alters insulin’s microvascular and metabolic actions. Protocol 3 determines whether Mas mediates Ang-(1-7)’s microvascular actions.

After a 30 min baseline period to ensure hemodynamic stability and a stable level of anesthesia, baseline microvascular parameters, including MBV, microvascular flow velocity (MFV) and microvascular blood flow (MBF), were determined on the proximal adductor muscle group (adductor magnus and semimembranosus) of the right hindlimb using contrast-enhanced ultrasound (CEU) and microbubble (Definity, Lantheus Medical Imaging) as the contrast agent, as previously described 27, 28. Rats then received a continuous intravenous infusion of Ang-(1-7) (0, 10 or 100 ng/kg/min) for 150 min (−30 – 120 min) without (Protocol 1) or with (Protocol 2) a hyperinsulinemic euglycemic clamp (3 mU/kg/min) superimposed on the last 120 min (0 – 120 min) (Figure 1). Additional rats were studied in the same fashion as Protocol 2 except all rats received a continuous infusion of A-779 (10 nmol/kg/min), a specific Mas inhibitor 29, which began 30 min prior to starting the Ang-(1-7) infusion (−60 – 120 min) (Protocol 3).

Microvascular parameters were determined at time points indicated in Figure 1 using CEU. Throughout the study, mean arterial blood pressure (MAP) was monitored via a sensor connected to the arterial catheter (Harvard Apparatus, Holliston, MA and ADInstruments, Inc., Colorado Springs, CO). Pentobarbital sodium was infused at a variable rate to maintain steady levels of anesthesia and blood pressure throughout the study. During the insulin clamp, arterial blood glucose was determined every 10 min using an Accu-Chek Advantage glucometer (Roche Diagnostics, Indianapolis, IN), and 30% dextrose was infused at a variable rate to maintain blood glucose within 10% of basal. At the end of each study the rat was sacrificed by a pentobarbital overdose and the gastrocnemius muscle was freeze-clamped in liquid nitrogen for later measurement of protein kinase B (Akt) and extracellular signal-regulated kinases 1/2 (ERK1/2) phosphorylation using Western blot analysis.

The study conforms to the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals published by the National Institutes of Health (publication No. 85-23, revised 1996). The study protocols were approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee of the University of Virginia.

Determination of protein phosphorylation

Muscle Akt and ERK1/2 phosphorylation was determined by Western blot analysis as described previously 13, 30–32. Primary antibodies against phospho-Akt (Ser473), total Akt, phospho-ERK (Thr202/Tyr204) and total ERK1/2 were obtained from Cell Signaling Technology (Beverly, MA). All blots were developed using enhanced chemiluminescence (GE Healthcare Bio-Sciences Corp, Piscataway, NJ). Autoradiographic films were scanned densitometrically and quantified using ImageQuant 3.3 software. Both the total and phosphospecific densities were quantified and the ratios of phosphospecific to total protein density calculated.

Assessment of Ang-(1-7)’s vasorelaxant effect on pre-constricted small arteries

The distal saphenous artery (≤ 250 μm) was dissected, cleaned of adhering connective tissues and cut into segments of ~2 mm in length. Each segment was mounted in a Multi Myograph System (Danish Myo Technology, Aarhus, Denmark). The organ chamber was filled with 6 mL physiological salt solution buffer (NaCl 130 mM, KCl 4.7 mM, CaCl2 1.6 mM, MgSO4 1.17 mM, KH2PO4 1.18 mM, NaHCO3 14.9 mM, EDTA 0.026 mM, glucose 5.5 mM; pH 7.4), which was constantly bubbled with 95% O2 – 5% CO2 and maintained at 37°C. Each ring was stretched initially to 5 mN and then allowed to stabilize at baseline tone. In some arteries, the endothelium was mechanically removed by rubbing the luminal surface of the ring with human hair. Functional removal of the endothelium was verified by the lack of relaxation response to acetylcholine. After pre-constriction of the arterial ring with 2 μM phenylephrine, Ang-(1-7) and/or insulin at various concentrations were added into the chamber. For the Mas inhibitor study, pre-constricted arterial rings were incubated with A-779 (20 μM) for 30 min before Ang-(1-7) was added. Changes in arterial tone were recorded.

Statistical Analysis

All data are presented as mean ± SEM. Statistical analyses were performed with SigmaStat 11.0 software (Systat Software, Inc), using either Student’s t-test or ANOVA with post-hoc analysis as appropriate. A p-value of < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Ang-(1-7) induces arterial relaxation via Mas in endothelium

Prior evidence has strongly suggested a direct vasodilatory action of Ang-(1-7) on microvessels, likely via a Mas-mediated, NO-dependent pathway 18, 33. Likewise, insulin also exerts potent vasodilatory action via increased NO production 34, 35. As such, we first examined whether Ang-(1-7) and insulin could potentiate each other’s vasodilatory actions in vitro (Figure 2). Using phenylephrine pre-constricted distal saphenous arteries, we found that Ang-(1-7) and insulin each induced dose-dependent vasorelaxation (p<0.05). Interestingly, insulin at high physiologic concentrations (1 nM) did not induce significant vasorelaxation but it markedly potentiated Ang-(1-7)’s vasodilatory effect (by up to 40%, p<0.01). Both endothelium denudement and pre-treatment with Mas inhibitor A-779 completely abolished Ang-(1-7)-induced vasorelaxation.

Figure 2.

Ang-(1-7) induces vasodilation via endothelium- and Mas-dependent mechanisms. Rat distal saphenous artery was isolated, pre-constricted with phenylephrine, and then incubated with various concentrations of Ang-(1-7) and/or insulin. A and B: Effect of Ang-(1-7) on intact or endothelium denuded arterial rings. n=6, * p<0.05. C and D: Effect of insulin. n=6, * p<0.05 vs. control. E and F: Effect of Ang-(1-7) in the presence of insulin (1 nM). n=6, #p<0.01 vs. control. G and H: Effect of Mas inhibition on Ang-(1-7)-induced vasodilation. n=6, * p<0.05. B, D, F and H: representative myographic tracings.

Ang-(1-7) recruits skeletal muscle microvasculature

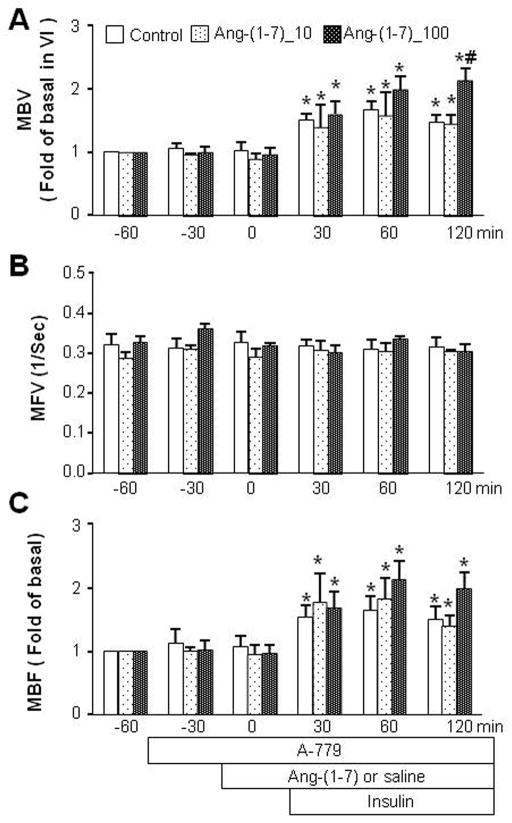

To examine the effect of Ang-(1-7) on the pre-capillary arterioles which control muscle microvascular perfusion 4, 36, we next used CEU to measure three important indices of the muscle microcirculation i.e. MBV, MFV and MBF before and during a continuous infusion of Ang-(1-7) at various concentrations. As shown in Figure 3, Ang-(1-7) dose-dependently increased muscle microvascular recruitment by increasing MBV within the first 30 min and this effect lasted for the entire 150 min infusion period while MFV was not affected. The increase of MBV led to a maximum increase in muscle MBF (by ~80%, p<0.05). Neither MAP nor blood glucose levels changed during Ang-(1-7) infusion (Tables 1 and 2).

Figure 3.

Effects of Ang-(1-7) on muscle microvascular recruitment. Each rat received a continuous intravenous infusion of Ang-(1-7) or saline (Control) for 150 min (−30 – 120 min). Ang-(1-7)_10: Ang-(1-7) at 10 ng/kg/min. Ang-(1-7)_100: Ang-(1-7) at 100 ng/kg/min. A: MBV; B: MFV; C: MBF. n=5 each. * p<0.05 vs control.

Table 1.

Blood glucose levels (mg/dL).

| Treatment | −60 min | −30 min | 0 min | 30 min | 60 min | 90 min | 120 min |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Protocol 1 | |||||||

| Control | n/a | 109±4.18 | 109±3.77 | 109±5.15 | 108±6.73 | 109±5.43 | 106±6.66 |

| Ang-(1-7)_10 | n/a | 112±4.22 | 110±5.45 | 110±6.26 | 108±4.95 | 109±5.32 | 108±5.86 |

| Ang-(1-7)_100 | n/a | 114±4.22 | 114±5.45 | 113±6.26 | 113±4.95 | 111±5.32 | 110±5.86 |

| Protocol 2 | |||||||

| Control | n/a | 112±1.94 | 110±1.66 | 109±2.8 | 108±2.57 | 111±2.74 | 110±2.23 |

| Ang-(1-7)_10 | n/a | 113±1.41 | 111±1.92 | 110±2.43 | 110±2.3 | 109±2.71 | 110±1.73 |

| Ang-(1-7)_100 | n/a | 111±2.07 | 110±2.53 | 105±2.4 | 107±2.54 | 108±2.6 | 109±3.11 |

| Protocol 3 | |||||||

| Control | 105±1.69 | 106±1.82 | 106±2.09 | 97±2.16 | 104±2.13 | 108±2.21 | 108±2.93 |

| Ang-(1-7)_10 | 108±3.7 | 109±3.84 | 110±4.28 | 105±3.7 | 103±5.36 | 109±3.2 | 110±3.76 |

| Ang-(1-7)_100 | 105±2.72 | 106±2.91 | 105±3.2 | 99±3.63 | 102±3.58 | 101±3.35 | 109±3.99 |

Ang-(1-7)_10: Ang-(1-7) at 10 ng/kg/min. Ang-(1-7)_100: Ang-(1-7) at 100 ng/kg/min.

Table 2.

Mean arterial pressure (mmHg).

| Treatment | −60 min | −30 min | 0 min | 30 min | 60 min | 90 min | 120 min |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Protocol 1 | |||||||

| Control | n/a | 120±5.07 | 120±6.11 | 121±2.49 | 116±4.76 | 119±6.43 | 120±5.22 |

| Ang-(1-7)_10 | n/a | 116±8.71 | 117±5.15 | 116±4.72 | 115±2.17 | 112±7.3 | 112±13.54 |

| Ang-(1-7)_100 | n/a | 121±8.71 | 120±5.15 | 117±4.72 | 120±2.17 | 116±7.3 | 113±13.54 |

| Protocol 2 | |||||||

| Control | n/a | 116±2.59 | 112±3.33 | 112±2.21 | 119±1.88 | 107±3.14 | 112±2.85 |

| Ang-(1-7)_10 | n/a | 111±3.28 | 112±0.94 | 107±2.93 | 106±1.76 | 109±1.73 | 108±2.66 |

| Ang-(1-7)_100 | n/a | 114±4.56 | 114±1.16 | 110±2.75 | 108±1.95 | 111±1.88 | 113±2.92 |

| Protocol 3 | |||||||

| Control | 113±2.47 | 112±2.47 | 113±2.3 | 116±2.88 | 115±1.31 | 115±3.35 | 112±2.76 |

| Ang-(1-7)_10 | 113±8.93 | 113±7.57 | 109±7.67 | 113±7.67 | 109±7.66 | 108±3.7 | 107±4.42 |

| Ang-(1-7)_100 | 124±1.96 | 121±1.74 | 119±3.71 | 119±3.75 | 117±1.96 | 119±4.29 | 115±1.52 |

Ang-(1-7)_10: Ang-(1-7) at 10 ng/kg/min. Ang-(1-7)_100: Ang-(1-7) at 100 ng/kg/min.

Ang-(1-7) enhances insulin’s vascular and metabolic actions

Knowing that Ang-(1-7) could indeed recruit muscle microvasculature and we and others have previously demonstrated that microvascular recruitment regulates insulin delivery and action in muscle 1,4, we next examined whether Ang-(1-7) could modulate insulin’s microvascular and metabolic actions in vivo. Similar to prior reports, insulin infusion alone increased both muscle MBV and MBF by ~60–70% (p<0.05) without affecting MFV (Figure 4). Administration of Ang-(1-7) prior to the initiation of insulin infusion recruited significantly more microvasculature than insulin alone. This was associated with ~30% increase (p<0.05) in insulin-mediated whole body glucose disposal (Figure 5). Neither MAP nor blood glucose levels changed during the entire procedure (Tables 1 and 2).

Figure 4.

Effects of Ang-(1-7) on muscle microvascular recruitment during insulin clamp. Each rat received a continuous intravenous infusion of Ang-(1-7) or saline (Control) for 150 min (−30 – 120 min) with an insulin clamp (3 mU/kg/min) superimposed on the last 120 min. Ang-(1-7)_10: Ang-(1-7) at 10 ng/kg/min. Ang-(1-7)_100: Ang-(1-7) at 100 ng/kg/min. A: MBV; B: MFV; C: MBF. n=5 each. * p<0.05 vs baseline (−30 min). # p<0.01 vs insulin alone.

Figure 5.

Ang-(1-7) dose-dependently augments insulin-stimulated whole body glucose disposal. Each rat received a continuous intravenous infusion of Ang-(1-7) or saline (Control) for 150 min with an insulin clamp (3 mU/kg/min) superimposed on the last 120 min. Ang-(1-7)_10: Ang-(1-7) at 10 ng/kg/min. Ang-(1-7)_100: Ang-(1-7) at 100 ng/kg/min. A: Time course of glucose infusion rate (GIR) during insulin clamp; B: GIR area under the curve during insulin clamp. n=5 each. * p<0.05 vs control.

Ang-(1-7)’s in vivo effects are Mas-dependent

Ang-(1-7) is an endogenous ligand for the G protein-coupled receptor Mas and our ex vivo myographic studies showed that Ang-(1-7)’s vasodilatory effect is indeed Mas dependent. We therefore tested whether Ang-(1-7)’s in vivo effects on the muscle microvasculature and insulin’s metabolic action are also mediated by Mas. As shown in Figure 6, inhibition of Mas with its specific antagonist A-779 abolished Ang-(1-7)-induced microvascular recruitment without affecting insulin-mediated increase in muscle MBV, evidenced by a lack of increase in MBV and MBF 30 min after Ang-(1-7) infusion (time 0 min) but a significant increase in MBV and MBF 30 min after beginning the insulin infusion (time 30 to 150 min). Interestingly, there is a tendency for Ang-(1-7), at 100 ng/kg/min, to synergize with insulin after 30 min to increase MBV and MBF, despite the presence of A-779 (p<0.05 at 120 min for MBV). These were coupled with a loss of the previously seen Ang-(1-7) enhancement of insulin-mediated glucose disposal (Figure 7). Neither MAP nor blood glucose levels changed during the entire procedure (Tables 1 and 2).

Figure 6.

Effects of Mas inhibition on Ang-(1-7) and insulin’s microvascular actions. Each rat received a continuous intravenous infusion of A-779 (10 nmol/kg/min) 30 min before Ang-(1-7) or saline infusion and 60 min before insulin clamp (3 mU/kg/min). Ang-(1-7)_10: Ang-(1-7) at 10 ng/kg/min. Ang-(1-7)_100: Ang-(1-7) at 100 ng/kg/min. A: MBV; B: MFV; C: MBF. n=5 each. * p<0.05 vs baseline (−60 min), # p<0.05 vs insulin alone.

Figure 7.

Mas inhibition abolishes Ang-(1-7)-mediated enhancement in insulin’s metabolic action. Each rat received a continuous intravenous infusion of A-779 (10 nmol/kg/min) 30 min before Ang-(1-7) or saline infusion and 60 min before insulin clamp (3 mU/kg/min). Ang-(1-7)_10: Ang-(1-7) at 10 ng/kg/min. Ang-(1-7)_100: Ang-(1-7) at 100 ng/kg/min. A: Time course of glucose infusion rate (GIR) during insulin clamp; B: GIR area under the curve during insulin clamp. n=5 each.

Effects of Ang-(1-7) on muscle Akt and ERK1/2 phosphorylation

Since Ang-(1-7) increased insulin’s metabolic action via a Mas-dependent signaling pathway, we measured the phosphorylation of muscle Akt and ERK1/2, two key signal intermediates in the insulin signaling pathways, in rats studied under all 3 protocols. As shown in Figure 8, insulin infusion significantly increased muscle Akt and ERK1/2 phosphorylation. While Ang-(1-7) infusion alone did not affect either Akt or ERK1/2 phosphorylation, it did further enhance insulin-mediated phosphorylation of these two proteins in a dose dependent fashion. A-779 pre-treatment completely abolished Ang-(1-7)’s effect without affecting insulin’s actions on either Akt or ERK1/2 phosphorylation.

Figure 8.

Effect of Ang-(1-7) on muscle Akt and ERK1/2 phosphorylation. A: Akt phosphorylation. B: ERK1/2 phosphorylation. n=4 each. * p<0.05 vs baseline [no insulin or A-779], # p<0.05 vs insulin alone.

DISCUSSION

In the current study we provide experimental evidence using both ex vivo arterial myographic and in vivo animal study approaches that Ang-(1-7) potently recruits muscle microvasculature and enhances insulin’s metabolic action and these actions are mediated by Mas in the endothelium.

Prior studies have confirmed that Ang-(1-7) exerts a potent vasodilatory action in various arterial beds 17, 18, 23, 37, 38. Ang-(1-7) counteracts the vasoconstrictor actions of Ang II and lowers blood pressure in transgenic (mRen2)27 hypertensive rats 39 and in spontaneously hypertensive rats 40. However, in the current study we did not observe a significant change in the mean arterial blood pressure during Ang-(1-7) infusion, likely secondary to the fact that our animals were not hypertensive and/or that the RAS was not up-regulated. Indeed, even chronic infusion of Ang-(1-7) failed to produce a significant change in blood pressure in the presence of high dietary salt intake and in normal rats. Ang-(1-7) likely is more important in the regulation of regional as opposed to systemic vascular resistance. Acute infusion of Ang-(1-7) leads to a significant change in regional blood flow distribution with a decrease in total peripheral resistance in Wistar rats 41. Similarly, expression of an Ang-(1-7)-producing fusion protein in rats elevates plasma Ang-(1-7) levels and reduces total peripheral resistance, which is associated with increased stroke volume and cardiac index 42. Although we did not assess cardiac parameters and peripheral vascular resistance, our findings that Ang-(1-7) significantly increased microvascular recruitment suggests that Ang-(1-7) is able to vasodilate muscle pre-capillary arterioles which control microvascular perfusion and are major contributors to total peripheral resistance.

The increased muscle microvascular recruitment seen with Ang-(1-7) infusion provides a physiological explanation for numerous study findings that Ang-(1-7) administration improves insulin sensitivity and action, as muscle microvasculature plays a critical role in the regulation of muscle insulin action by providing the endothelial exchange surface area and actively regulating insulin delivery to the muscle interstitium. Indeed, it is the insulin concentrations in the muscle interstitium, not in plasma, that best correlate with insulin’s muscle metabolic action and whole body glucose disposal 43. A recent study demonstrates that in rats Ang-(1-7) by itself does not promote glucose transport but significantly increases insulin-stimulated glucose disposal 44. This lends further support to our study findings. We and others have previously demonstrated that factors that are able to recruit microvasculature, such as low intensity exercise 27,28, AT1R blockade 13,14, adiponectin 45, ranolazine 32, and GLP-1 46, all significantly increase muscle insulin delivery and action. That Ang-(1-7)-induced microvascular recruitment is associated with increased whole body glucose disposal and muscle Akt and ERK1/2 phosphorylation during insulin clamp is certainly consistent with increased muscle delivery and action of insulin.

Our observations that the combination of Ang-(1-7) and insulin (1 nM) exerted an enhanced vasodilatory action compared to Ang-(1-7) or insulin alone ex vivo and that the MBV increase in vivo was also greater with combined insulin plus Ang-(1-7) infusion compared to either agent alone, suggest that Ang-(1-7) and insulin exert additive or synergistic vasodilatory actions on the pre-capillary arterioles. This is not surprising as insulin 34, 35 and Ang-(1-7) 17, 18 each engenders vasorelaxation via a NO-dependent pathway and high NO production, as seen in the case of GLP-1 and losartan, can increase MBV by 2–3-fold 13, 14, 46.

Though prior studies have reported that Ang-(1-7) stimulated muscle Akt phosphorylation and this was completely inhibited by the co-administration of Mas inhibitor A-779 47, 48, Ang-(1-7) alone did not increase muscle Akt phosphorylation in the current study. This discrepancy likely resulted from the difference in timing of muscle sample collection for Akt phosphorylation analysis (5 min in prior reports vs. 150 min in the current study). Similarly, Ang-(1-7) did not alter ERK1/2 phosphorylation. It is certainly possible that Ang-(1-7) could acutely phosphorylate muscle Akt and ERK1/2 but this effect is not sustained. The lack of Ang-(1-7) enhancement of insulin-mediated Akt and ERK1/2 phosphorylation during A-779 infusion is consistent with the findings that Mas inhibition blunts Ang-(1-7)-mediated microvascular recruitment and enhancement in insulin-stimulated whole body glucose disposal. Thus, our study results strongly suggest that Ang-(1-7) recruits muscle microvasculature and increases microvascular endothelial surface area which lead to increased muscle delivery thus interstitial concentrations and action of insulin. Though the Western blot results should be interpreted with caution as we did not separate myocytes from other cell types such as endothelial cells, vascular smooth muscle cells, and fibroblasts, our results most likely reflect the findings in myocytes given its dominance in number in muscle.

Although expression of Mas in endothelial cells is well-documented and Mas has been repeatedly shown to mediate Ang-(1-7)’s vasodilatory actions, several studies have suggested that Ang-(1-7) may exert vasorelaxation via AT2R activation 49, 50 or by antagonizing AT1R 51, 52. While we have previously reported that basal AT1R tone restricts and basal AT2R activity enhances muscle MBV 12, it is unlikely that Ang-(1-7) acted directly on the AT1R to exert its biological effects in our study due to its extremely low affinity for AT1R 53. It remains possible that Ang-(1-7) regulates AT1R function via Mas which is a physiological antagonist of AT1R 54. Our finding that pre-treatment with Mas antagonist A-779 blocks both Ang-(1-7)’s vasodilatory actions on isolated arterioles ex vivo and precapillary arterioles in vivo confirms that Mas plays a key role in this process. However, our observations that Mas inhibition completely abolished the Ang-(1-7)-mediated increase in MBV and its potentiation on insulin’s microvascular action at 10 but not at 100 ng/kg/min are somewhat puzzling. This may reflect that microvessels undergo a non-specific loss of tension mediated by NO 18 or non-Mas-mediated effects of Ang-(1-7) at high concentrations. Indeed, Ang-(1-7) is capable of binding to AT2R directly though at much lower affinity than Ang II 53. Further study is warranted.

Perspectives.

Muscle microvasculature plays a critical role in the regulation of muscle delivery of nutrients and hormones including insulin by providing endothelial exchange surface area. Ang-(1-7) has been shown to cause arterial dilation and increase insulin sensitivity. Our current results demonstrate that acute administration of Ang-(1-7) potently recruits muscle microvasculature via its receptor Mas in the endothelium which expands the microvascular exchange surface area and thus enhances insulin’s metabolic action in muscle. These effects may contribute to the cardiovascular protective responses associated with Mas activation and explain the insulin sensitizing action of Ang-(1-7).

Novelty and Significance.

What Is New?

Ang-(1-7) potently recruits microvasculature to increase endothelial exchange surface area in muscle.

Ang-(1-7) and insulin exerts additive/synergistic actions on the pre-capillary arterioles.

Ang-(1-7) enhances insulin’s metabolic actions in muscle.

Mas inhibition abolishes Ang-(1-7)’s microvascular and insulin-sensitizing effects.

What Is Relevant?

Mas plays a pivotal role in Ang-(1-7)-mediated microvascular recruitment and insulin sensitization.

This may contribute to the cardiovascular protective responses associated with Mas activation and explain Ang-(1-7)’s insulin sensitizing action.

Summary

Ang-(1-7) by activating Mas recruits muscle microvasculature and enhances insulin’s metabolic action.

Acknowledgments

SOURCES OF FUNDING:

This work was supported by American Diabetes Association grant 1-11-CR-30 and National Institutes of Health grant R01HL094722 (to Z.L.). Z.F. was supported by a T32 training grant to the University of Virginia (1-T32-DK07646).

Footnotes

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTION:

Zhuo Fu, Lina Zhzo, Kevin Aylor and Zhenqi Liu researched data. Robert Carey and Eugene Barrett contributed to discussion. Zhuo Fu and Zhenqi Liu wrote the manuscript.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST/DISCLOSURE:

We declare no conflict of interest in this study.

References

- 1.Vincent MA, Clerk LH, Lindner JR, Klibanov AL, Clark MG, Rattigan S, Barrett EJ. Microvascular recruitment is an early insulin effect that regulates skeletal muscle glucose uptake in vivo. Diabetes. 2004;53:1418–1423. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.53.6.1418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barrett EJ, Wang H, Upchurch CT, Liu Z. Insulin regulates its own delivery to skeletal muscle by feed-forward actions on the vasculature. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2011;301:E252–263. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00186.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Clark MG, Wallis MG, Barrett EJ, Vincent MA, Richards SM, Clerk LH, Rattigan S. Blood flow and muscle metabolism: A focus on insulin action. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2003;284:E241–258. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00408.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Barrett EJ, Eggleston EM, Inyard AC, Wang H, Li G, Chai W, Liu Z. The vascular actions of insulin control its delivery to muscle and regulate the rate-limiting step in skeletal muscle insulin action. Diabetologia. 2009;52:752–764. doi: 10.1007/s00125-009-1313-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Carey RM, Siragy HM. Newly recognized components of the renin-angiotensin system: Potential roles in cardiovascular and renal regulation. Endocr Rev. 2003;24:261–271. doi: 10.1210/er.2003-0001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ko SH, Cao W, Liu Z. Hypertension management and microvascular insulin resistance in diabetes. Curr Hypertens Rep. 2010;12:243–251. doi: 10.1007/s11906-010-0114-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Liu Z. The renin-angiotensin system and insulin resistance. Curr Diab Rep. 2007;7:34–42. doi: 10.1007/s11892-007-0007-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Andreozzi F, Laratta E, Sciacqua A, Perticone F, Sesti G. Angiotensin II impairs the insulin signaling pathway promoting production of nitric oxide by inducing phosphorylation of insulin receptor substrate-1 on ser312 and ser616 in human umbilical vein endothelial cells. Circ Res. 2004;94:1211–1218. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000126501.34994.96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Velloso LA, Folli F, Sun XJ, White MF, Saad MJ, Kahn CR. Cross-talk between the insulin and angiotensin signaling systems. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:12490–12495. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.22.12490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wei Y, Sowers JR, Nistala R, Gong H, Uptergrove GM, Clark SE, Morris EM, Szary N, Manrique C, Stump CS. Angiotensin II-induced nadph oxidase activation impairs insulin signaling in skeletal muscle cells. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:35137–35146. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M601320200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wei Y, Sowers JR, Clark SE, Li W, Ferrario CM, Stump CS. Angiotensin II-induced skeletal muscle insulin resistance mediated by nf-kappab activation via nadph oxidase. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2008;294:E345–351. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00456.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chai W, Wang W, Liu J, Barrett EJ, Carey RM, Cao W, Liu Z. Angiotensin II type 1 and type 2 receptors regulate basal skeletal muscle microvascular volume and glucose use. Hypertension. 2010;55:523–530. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.109.145409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chai W, Wang W, Dong Z, Cao W, Liu Z. Angiotensin II receptors modulate muscle microvascular and metabolic responses to insulin in vivo. Diabetes. 2011;60:2939–2946. doi: 10.2337/db10-1691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wang N, Chai W, Zhao L, Tao L, Cao W, Liu Z. Losartan increases muscle insulin delivery and rescues insulin’s metabolic action during lipid infusion via microvascular recruitment. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2013;304:E538–545. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00537.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jonk AM, Houben AJ, Schaper NC, de Leeuw PW, Serne EH, Smulders YM, Stehouwer CD. Acute angiotensin II receptor blockade improves insulin-induced microvascular function in hypertensive individuals. Microvasc Res. 2011;82:77–83. doi: 10.1016/j.mvr.2011.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jonk AM, Houben AJ, Schaper NC, de Leeuw PW, Serne EH, Smulders YM, Stehouwer CD. Angiotensin II enhances insulin-stimulated whole-body glucose disposal but impairs insulin-induced capillary recruitment in healthy volunteers. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2010;95:3901–3908. doi: 10.1210/jc.2009-2587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Brosnihan KB, Li P, Tallant EA, Ferrario CM. Angiotensin-(1-7): A novel vasodilator of the coronary circulation. Biol Res. 1998;31:227–234. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Peiro C, Vallejo S, Gembardt F, Palacios E, Novella S, Azcutia V, Rodriguez-Manas L, Hermenegildo C, Sanchez-Ferrer CF, Walther T. Complete blockade of the vasorelaxant effects of angiotensin-(1-7) and bradykinin in murine microvessels by antagonists of the receptor Mas. J Physiol. 2013;591:2275–2285. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2013.251413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Prasannarong M, Santos FR, Henriksen EJ. Ang-(1-7) reduces ang II-induced insulin resistance by enhancing akt phosphorylation via a mas receptor-dependent mechanism in rat skeletal muscle. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2012;426:369–373. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2012.08.093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Giani JF, Mayer MA, Munoz MC, Silberman EA, Hocht C, Taira CA, Gironacci MM, Turyn D, Dominici FP. Chronic infusion of angiotensin-(1-7) improves insulin resistance and hypertension induced by a high-fructose diet in rats. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2009;296:E262–271. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.90678.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Marcus Y, Shefer G, Sasson K, Kohen F, Limor R, Pappo O, Nevo N, Biton I, Bach M, Berkutzki T, Fridkin M, Benayahu D, Shechter Y, Stern N. Angiotensin 1-7 as means to prevent the metabolic syndrome: lessons from the fructose-fed rat model. Diabetes. 2013;62:1121–1130. doi: 10.2337/db12-0792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Santos SH, Braga JF, Mario EG, Porto LC, da Rodrigues-Machado MG, Murari A, Botion LM, Alenina N, Bader M, Santos RA. Improved lipid and glucose metabolism in transgenic rats with increased circulating angiotensin-(1-7) Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2010;30:953–961. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.109.200493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Santos RA, Simoes e Silva AC, Maric C, Silva DM, Machado RP, de Buhr I, Heringer-Walther S, Pinheiro SV, Lopes MT, Bader M, Mendes EP, Lemos VS, Campagnole-Santos MJ, Schultheiss HP, Speth R, Walther T. Angiotensin-(1-7) is an endogenous ligand for the g protein-coupled receptor mas. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:8258–8263. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1432869100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gironacci MM, Adamo HP, Corradi G, Santos RA, Ortiz P, Carretero OA. Angiotensin (1-7) induces mas receptor internalization. Hypertension. 2011;58:176–181. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.111.173344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sampaio WO, Souza dos Santos RA, Faria-Silva R, da Mata Machado LT, Schiffrin EL, Touyz RM. Angiotensin-(1-7) through receptor mas mediates endothelial nitric oxide synthase activation via akt-dependent pathways. Hypertension. 2007;49:185–192. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000251865.35728.2f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Peiro C, Vallejo S, Gembardt F, Azcutia V, Heringer-Walther S, Rodriguez-Manas L, Schultheiss HP, Sanchez-Ferrer CF, Walther T. Endothelial dysfunction through genetic deletion or inhibition of the g protein-coupled receptor mas: A new target to improve endothelial function. J Hypertens. 2007;25:2421–2425. doi: 10.1097/HJH.0b013e3282f0143c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Inyard AC, Chong DG, Klibanov AL, Barrett EJ. Muscle contraction, but not insulin, increases microvascular blood volume in the presence of free fatty acid-induced insulin resistance. Diabetes. 2009;58:2457–2463. doi: 10.2337/db08-1077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Inyard AC, Clerk LH, Vincent MA, Barrett EJ. Contraction stimulates nitric oxide independent microvascular recruitment and increases muscle insulin uptake. Diabetes. 2007;56:2194–2200. doi: 10.2337/db07-0020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kucharewicz I, Pawlak R, Matys T, Pawlak D, Buczko W. Antithrombotic effect of captopril and losartan is mediated by angiotensin-(1-7) Hypertension. 2002;40:774–779. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.0000035396.27909.40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Li G, Barrett EJ, Wang H, Chai W, Liu Z. Insulin at physiological concentrations selectively activates insulin but not insulin-like growth factor I (IGF-I) or insulin/IGF-I hybrid receptors in endothelial cells. Endocrinology. 2005;146:4690–4696. doi: 10.1210/en.2005-0505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Li G, Barrett EJ, Barrett MO, Cao W, Liu Z. Tumor necrosis factor-α induces insulin resistance in endothelial cells via a p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase-dependent pathway. Endocrinology. 2007;148:3356–3363. doi: 10.1210/en.2006-1441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fu Z, Zhao L, Chai W, Dong Z, Cao W, Liu Z. Ranolazine recruits muscle microvasculature and enhances insulin action in rats. J Physiol. 2013;591:5235–5249. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2013.257246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Heitsch H, Brovkovych S, Malinski T, Wiemer G. Angiotensin-(1-7)-stimulated nitric oxide and superoxide release from endothelial cells. Hypertension. 2001;37:72–76. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.37.1.72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Steinberg HO, Brechtel G, Johnson A, Fineberg N, Baron AD. Insulin-mediated skeletal muscle vasodilation is nitric oxide dependent. A novel action of insulin to increase nitric oxide release. J Clin Invest. 1994;94:1172–1179. doi: 10.1172/JCI117433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Scherrer U, Randin D, Vollenweider P, Vollenweider L, Nicod P. Nitric oxide release accounts for insulin’s vascular effects in humans. J Clin Invest. 1994;94:2511–2515. doi: 10.1172/JCI117621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Liu Z, Ko SH, Chai W, Cao W. Regulation of muscle microcirculation in health and diabetes. Diabetes Metab J. 2012;36:83–89. doi: 10.4093/dmj.2012.36.2.83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ren Y, Garvin JL, Carretero OA. Vasodilator action of angiotensin-(1-7) on isolated rabbit afferent arterioles. Hypertension. 2002;39:799–802. doi: 10.1161/hy0302.104673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.van Twist DJ, Houben AJ, de Haan MW, Mostard GJ, Kroon AA, de Leeuw PW. Angiotensin-(1-7)-induced renal vasodilation in hypertensive humans is attenuated by low sodium intake and angiotensin II co-infusion. Hypertension. 2013;62:789–793. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.113.01814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Garcia-Espinosa MA, Shaltout HA, Gallagher PE, Chappell MC, Diz DI. In vivo expression of angiotensin-(1-7) lowers blood pressure and improves baroreflex function in transgenic (mren2)27 rats. Journal of cardiovascular pharmacology. 2012;60:150–157. doi: 10.1097/FJC.0b013e3182588b32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Benter IF, Ferrario CM, Morris M, Diz DI. Antihypertensive actions of angiotensin-(1-7) in spontaneously hypertensive rats. Am J Physiol. 1995;269:H313–319. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1995.269.1.H313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sampaio WO, Nascimento AA, Santos RA. Systemic and regional hemodynamic effects of angiotensin-(1-7) in rats. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2003;284:H1985–1994. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01145.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Botelho-Santos GA, Sampaio WO, Reudelhuber TL, Bader M, Campagnole-Santos MJ, Souza dos Santos RA. Expression of an angiotensin-(1-7)-producing fusion protein in rats induced marked changes in regional vascular resistance. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2007;292:H2485–2490. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01245.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Castillo C, Bogardus C, Bergman R, Thuillez P, Lillioja S. Interstitial insulin concentrations determine glucose uptake rates but not insulin resistance in lean and obese men. J Clin Invest. 1994;93:10–16. doi: 10.1172/JCI116932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Echeverria-Rodriguez O, Del Valle-Mondragon L, Hong E. Angiotensin 1-7 improves insulin sensitivity by increasing skeletal muscle glucose uptake in vivo. Peptides. 2014;51:26–30. doi: 10.1016/j.peptides.2013.10.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zhao L, Chai W, Fu Z, Dong Z, Aylor KW, Barrett EJ, Cao W, Liu Z. Globular adiponectin enhances muscle insulin action via microvascular recruitment and increased insulin delivery. Circ Res. 2013;112:1263–1271. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.111.300388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Chai W, Dong Z, Wang N, Wang W, Tao L, Cao W, Liu Z. Glucagon-like peptide 1 recruits microvasculature and increases glucose use in muscle via a nitric oxide-dependent mechanism. Diabetes. 2012;61:888–896. doi: 10.2337/db11-1073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Munoz MC, Giani JF, Dominici FP. Angiotensin-(1-7) stimulates the phosphorylation of akt in rat extracardiac tissues in vivo via receptor mas. Regul Pept. 2010;161:1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.regpep.2010.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Giani JF, Gironacci MM, Munoz MC, Pena C, Turyn D, Dominici FP. Angiotensin-(1-7) stimulates the phosphorylation of jak2, irs-1 and akt in rat heart in vivo: Role of the AT1 and mas receptors. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2007;293:H1154–1163. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01395.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bosnyak S, Widdop RE, Denton KM, Jones ES. Differential mechanisms of ang (1-7)-mediated vasodepressor effect in adult and aged candesartan-treated rats. Int J Hypertens. 2012;2012:192567. doi: 10.1155/2012/192567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Walters PE, Gaspari TA, Widdop RE. Angiotensin-(1-7) acts as a vasodepressor agent via angiotensin II type 2 receptors in conscious rats. Hypertension. 2005;45:960–966. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000160325.59323.b8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Dilauro M, Burns KD. Angiotensin-(1-7) and its effects in the kidney. Scientific WorldJournal. 2009;9:522–535. doi: 10.1100/tsw.2009.70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Katovich MJ, Grobe JL, Raizada MK. Angiotensin-(1-7) as an antihypertensive, antifibrotic target. Curr Hypertens Rep. 2008;10:227–232. doi: 10.1007/s11906-008-0043-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Bosnyak S, Jones ES, Christopoulos A, Aguilar MI, Thomas WG, Widdop RE. Relative affinity of angiotensin peptides and novel ligands at at1 and at2 receptors. Clin Sci (Lond) 2011;121:297–303. doi: 10.1042/CS20110036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kostenis E, Milligan G, Christopoulos A, Sanchez-Ferrer CF, Heringer-Walther S, Sexton PM, Gembardt F, Kellett E, Martini L, Vanderheyden P, Schultheiss HP, Walther T. G-protein-coupled receptor mas is a physiological antagonist of the angiotensin II type 1 receptor. Circulation. 2005;111:1806–1813. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000160867.23556.7D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]