Abstract

Posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and alcohol dependence (AD) frequently co-occur, although results of both cross-sectional and longitudinal studies evaluating the nature of their relationship have been mixed. There has been varied support for competing models explaining how these conditions influence one another. To assess both the self-medication and mutual maintenance models, as well as examine the potential moderating role of drinking motives, the current study used Generalized Estimating Equations to evaluate daily associations for an average of 7.3 days between PTSD symptoms and alcohol use in a mixed-gender sample of individuals who met criteria for both PTSD and AD. Results generally supported a self-medication model with elevated PTSD symptoms predictive of greater alcohol use on that same day and on the following day. Contrary to a mutual maintenance model prediction, drinking did not predict next-day PTSD symptoms. Results also indicated that both coping and enhancement drinking motives were significant moderators of the PTSD and drinking relationships, suggesting that these relationships may be more or less salient depending on an individual’s particular drinking motivations. For example, among those higher on coping drinking motives, a 1-unit increase in PTSD symptom severity was associated with a 37% increase in amount of alcohol consumed the same day, while among those low on coping drinking motives, a 1-unit PTSD increase was associated with only a 10% increase in alcohol consumption. We discuss implications of these findings for the larger literature on the associations between PTSD and alcohol use as well as for clinical interventions.

Keywords: PTSD, alcohol use, drinking motives, daily monitoring

Alcohol use disorders (AUD) are among the most common psychiatric problems in the U.S., with lifetime prevalence estimates ranging from 13.2% to 17.8% for alcohol abuse and from 5.4% to 12.5% for alcohol dependence (DSM-IV AD; Hasin, Stinson, Ogburn, & Grant, 2007; Kessler, Berglund, Demler, Merikangas, & Walters, 2005). Worldwide, alcohol use is associated with tremendous societal costs with an estimated 3.8% of all global deaths attributable to alcohol consumption (Rehm, Mathers, Popova, Thavorncharoensap, Teerawattananon, & Patra, 2009). In addition, relative to those without an AUD, individuals with a current AUD are more likely to meet diagnostic criteria for PTSD (Kessler, Crum, Warner, Nelson, Schulenberg, & Anthony, 1997; note: DSM-III-R was used in this study). The U.S. National Comorbidity Study found that compared with those without AD, men and women with a lifetime diagnosis of AD had 3.2 and 3.6 times the risk of also having a lifetime diagnosis of PTSD, respectively (Kessler et al., 1997).

Theoretical Explanations of Co-Occurring PTSD and AUD

Four main ideas have been put forth to explain the relationship between PTSD and substance use disorders (SUDs). These include 1) the negative reinforcement or self-medication model (Baker, Piper, Fiore, McCarthy, & Majeskie, 2004; Khantzian, 2003), which maintains that the substance is consumed to quell symptom-related distress and the associated relief reinforces continued substance use eventually leading to SUDs; 2) the mutual maintenance model, which purports that there is a reflexive relationship between the two conditions, such that PTSD symptoms lead to drinking or drug use and in turn, that substance use exacerbates, or at least maintains, PTSD symptoms (Kaysen, Atkins, Moore, Lindgren, Dillworth, & Simpson, 2011; McFarlane et al., 2009); 3) the lifestyle risk model, which posits that substance use leads to greater incidence of trauma exposure, and thus, PTSD (Begle et al., 2011; McFarlane et al., 2009); and 4) a common factors explanation, which suggests that both disorders are driven by a third variable, such as shared genetic variance (Sartor et al., 2011) or personality factors (Ferrier-Auerbach Kehle, Erbes, Arbisi, Thuras, & Poulsny, 2009; Haller & Chassin, 2012; Miller, Vogt, Mozley, Kaloupek, & Keane, 2006).

Numerous attempts have been made to evaluate the explanatory strengths of these models using various study designs. These include cross-sectional and longitudinal epidemiological and community-based studies (Begle et al., 2011; Cerda, Tracy, & Galea, 2011; Kaysen et al., 2011; Leeise, Pagura, Sareen, & Bolton, 2010; Wolitzky-Taylor, Bobova, Zinbarg, Mineka, & Craske, 2012) and treatment outcome studies involving individuals with PTSD and AUD (Hien et al., 2010). Other approaches have included experimental psychopathology laboratory studies involving craving induction (Coffey, Schumacher, Stasiewicz, Henslee, Baillie, & Landy, 2010), and micro-longitudinal studies that attempt to capture the day-to-day interplay between symptoms and alcohol use or craving (Cleveland & Harris, 2010; Oslin, Cary, Slaymaker, Colleran, & Blow, 2009; Kaysen et al., in press; Simpson, Stappenbeck, Varra, Moore, & Kaysen, 2012). Results from these studies are mixed with support having been found for all four models: self-medication (Begle et al., 2011; Cerda et al., 2011; Leeise et al., 2010; Marshall, Prescott, Liberzon, Tamburrino, Calabrese, & Galea, 2012; Ouimette, Read, Wade, & Tirone, 2010; Wolitzky-Taylor et al, 2012), mutual maintenance (Hruska, Fallon, Spoonster, Sledjeski, & Delahanty, 2011; Kaysen, Simpson, Dillworth, Gunter, Larimer, & Resick, 2006), life-style risk (Begle et al., 2011; McFarlane et al., 2009), and common factors (Ferrier-Auerbach et al., 2009; Miller et al., 2006; Sartor et al., 2011).

Although it would be ideal to thoroughly evaluate these four models in one study, methodological challenges make that a difficult endeavor. It is most common, therefore, to evaluate only one model at a time, though two longitudinal studies of adolescents have evaluated both the self-medication and life-style risk models (Begle et al., 2011; Wolitzky-Taylor et al., 2012) as have two studies involving adult women (Najdowski & Ullman, 2009; Testa, Livingson, & Hoffman, 2007; Testa, VanZile-Tamsen, & Livingston, 2007; note: the two Testa articles are based on the same sample). To our knowledge, however, the self-medication model and the mutual maintenance models have not been examined simultaneously in prospective studies. Establishing the relative strength of these two models, particularly once both disorders are established, is important because the treatment implications for each are different. For example, a clinician’s approach would likely vary if PTSD symptom severity was associated with future drinking (i.e., self-medication), as opposed to if the drinking itself was also responsible for an increase or maintenance of PTSD symptoms (i.e., mutual maintenance).

Methodological Considerations

Browne, Stout, and Gannon-Rowley (1998) surveyed individuals in SUD treatment with comorbid PTSD and found that most participants believed that elevated PTSD symptoms led to more drinking, which would be consistent with the self-medication model. These individuals also reported that increased drinking did not lead to increased PTSD, which is inconsistent with the mutual maintenance model. However, traditional retrospective symptom and behavior assessments (e.g., Leesie et al., 2010; Ouimette et al., 2010) are subject to bias and cannot capture the interplay between alcohol use and PTSD as they unfold temporally from day-to-day. In light of their advantages over traditional retrospective methods (Leigh, 2000), daily monitoring protocols are being applied to studies of the relationship between alcohol use and other phenomena such as anxiety, negative affect, motives for drinking, and coping (Armelli, Conner, Cullum, & Tennen, 2010). This type of fine-grained evaluation of alcohol use and PTSD would allow for a more nuanced examination of these symptoms, and thus a better understanding of how best to target treatment interventions.

The extant research on daily associations between alcohol and PTSD, however, is limited. Possemato and her colleagues (2012) collected daily data on substance use and PTSD symptoms and have reported on compliance and reactivity but not yet on associations between these phenomena. In a daily diary study of PTSD symptoms and alcohol use in young college women, on days women experienced more PTSD symptoms they were more likely to drink and experience cravings (Kaysen et al, in press). A daily monitoring study of individuals entering outpatient treatment for AD found that greater PTSD severity on a given day was associated with greater alcohol craving that same day (Simpson et al., 2012), but drinking was not evaluated.

One of the key questions when evaluating either the self-medication or the mutual maintenance model is the time lag in which to examine the temporal relationship between PTSD symptomatology and alcohol use. Although the ideal time lag is not currently known, from a clinical perspective, if someone has had a PTSD exacerbation we might expect to see the strongest association between PTSD symptoms and drinking within that same day. Additionally, a one-day lag would allow for the examination of potential carry-over of one’s PTSD symptoms from one day to the next (e.g., the individual still feels so shaky and unsettled from the previous day’s PTSD exacerbation that they drink to cope). Similarly, a one-day lag would allow one to evaluate whether more drinking on a given day leads to worse PTSD symptoms the next day, perhaps related to withdrawal and other physical alcohol effects (e.g., increased irritability, hypervigilance, poor sleep quality) or greater social or intra-personal consequences (e.g., greater detachment from others, feelings of guilt or shame).

The Moderating Influence of Drinking Motives

In addition to the outstanding questions regarding how best to evaluate the relationship between PTSD symptoms and drinking behaviors, it is unknown whether the drinking motives reported by individuals with comorbid PTSD and AD influence the relationship between these phenomena. In the larger alcohol literature, motivational models of alcohol use have been helpful in improving our understanding of the reasons individuals may choose to drink alcohol (Cooper, 1994). If the self-medication model is robust and the best explanation for the relationship between PTSD and drinking, we would expect that a large majority of those with comorbid PTSD and AD would be primarily motivated to drink to cope with negative affect, especially if they perceive that alcohol is an effective means of managing distress. There is a consistent body of literature demonstrating that those with comorbid PTSD and AUD report being motivated to drink to cope with negative affect (Dixon, Leen-Feldner, Ham, Feldner, & Lewis, 2009; Grayson, & Nolen-Hoeksema, 2005; Kaysen, Dillworth, Simpson, Waldrop, Larimer, & Resick, 2007; Miranda, Meyerson, Long, Marx, & Simpson, 2002; Nugent, Lally, Brown, Knopik, & McGeary, 2012; Simpson, 2003; Ullman, Filipas, Townsend, & Starzynski, 2005). However, the extant literature on drinking motives among those with comorbid PTSD and AUD also suggests that enhancement drinking motives (e.g., drinking to increase positive affect) may be salient for this group (Grayson, & Nolen-Hoeksema, 2005; Miranda et al., 2002; Nugent et al., 2012; Simpson, 2003; Ullman et al., 2005), and this may have clinical and conceptual implications for our understanding of the relationship between PTSD and AUD.

Social drinking motives, or drinking to achieve positive social rewards (Cooper, 1994), represent another set of reasons for drinking that could have important clinical and conceptual implications. In light of the relatively high rate of social avoidance behavior found among those with PTSD (Hofmann, Litz, & Weathers, 2003), it is possible that those with comorbid PTSD and AUD drink in order to make social gatherings more enjoyable and to be more sociable. Indeed, among a sample of binge drinkers living with HIV, PTSD severity was associated with social drinking motives as well as with coping and enhancement drinking motives (Nugent et al., 2012). The fourth commonly assessed drinking motive, conformity (e.g., drinking to fit in with others), has not been evaluated in the context of the relationship between alcohol use and PTSD symptomatology to the authors’ knowledge.

The inclusion of information on drinking motives in models evaluating the daily relationships between PTSD symptoms and alcohol consumption may clarify why the self-medication and mutual maintenance findings, in particular, have been so mixed. The evaluation of drinking motives may also help identify for whom each of these models are most relevant or may suggest ways that the existing models need to be refined so that they are more accurate and have better clinical applicability.

Present Study

The present study utilized data from the initial pre-treatment daily monitoring period involving a sample of individuals with comorbid PTSD and AD participating in a larger experimental treatment study evaluating mechanisms of behavior change. We evaluated both the self-medication and mutual maintenance models. In this sample of individuals with established comorbid PTSD and AD, it was not possible to evaluate the lifestyle risk hypothesis. Additionally, although it would have been possible to explore the third variable hypothesis in this sample by evaluating whether personality factors or family history of PTSD or alcohol use disorders moderated the relationship between PTSD and alcohol use, such data were not available and outside of the scope of the original study.

To assess the self-medication model we examined whether overall PTSD symptom severity was predictive of alcohol consumption, testing both same-day and next-day associations. We hypothesized that PTSD symptom severity would be associated with both same-day and next-day alcohol consumption. To examine the mutual maintenance model, we examined whether alcohol consumption was predictive of both same-day and next-day PTSD symptomatology. We also hypothesized that amount of alcohol use would be associated with same-day and next-day PTSD symptom severity.

Because drinking motives may influence the self-medication relationship between PTSD symptoms and drinking behavior, we evaluated the moderating roles of participants’ baseline coping, enhancement, social, and conformity drinking motives on the relationship between PTSD symptoms and same-day and next-day drinking. We expected that coping and enhancement drinking motives would moderate the relationship between PTSD symptomatology and drinking. We did not anticipate that social or conformity motives would moderate the PTSD and drinking relationship. Drinking motives were not expected to moderate the relationship between alcohol consumption and next-day PTSD symptoms (e.g., drinking to cope is unlikely to influence PTSD severity experienced the day after drinking); thus, this was not evaluated.

Methods

Participants

Ninety-two participants met inclusion/exclusion criteria for the study. The final sample included here consisted of those who provided at least 50% of the daily monitoring data. Three potential participants were excluded because they did not complete any monitoring days, and an additional three potential participants were excluded for having less than 50% of observations available of their total number of monitoring days (see Table 1 for participant characteristics). The final study sample was composed of 86 (49% female) civilians (n = 64; 74%) and veterans (n = 22; 26%) with comorbid PTSD and AD who indicated a desire to decrease alcohol use as part of a larger study registered through ClinicalTrials.gov (protocol #: NCT00760994).

Table 1.

Participant Characteristics

| Characteristics | Mean (SD) or N (%) |

|---|---|

| Female | 42 (49.0) |

| Age(M ± SD) | 44.7 (11.0) |

| Ethnicity/Race | |

| Caucasian | 34 (39.5) |

| African American | 37 (43.0) |

| Hispanic/Latino | 4 (4.7) |

| Native American | 4 (4.7) |

| Asian American | 1 (1.2) |

| Other or missing | 6 (7.0) |

| Marital Status | |

| Married or partnered | 11 (13.1) |

| Divorced or separated | 32 (36.9) |

| Never married | 36 (42.0) |

| Widowed or other | 7 (8.4) |

| Housing Stats | |

| Living in own home | 53 (61.6) |

| Homeless | 20 (23.3) |

| Other | 13 (15.1) |

| Educational Attainment | |

| Did not graduate HS | 19 (22.1) |

| Graduated HS | 13 (15.1) |

| At least some college | 54 (62.8) |

| Employment Status | |

| Employed at least part-time | 11 (12.8) |

| Unemployed | 27 (31.4) |

| Student | 9 (10.5) |

| Disabled/Retired/Other | 39 (45.3) |

| Treatment History | |

| Inpatient substance abuse | 42 (48.8) |

| Inpatient mental health | 23 (26.7) |

| Medication management | 51 (59.1) |

| Outpatient therapy | 50 (68.6) |

Inclusion criteria were: 1) age ≥ 18 years; 2) current diagnosis of AD as defined by the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition (DSM-IV; American Psychiatric Association [APA], 1994) with alcohol use in the last two weeks; 3) current DSM-IV diagnosis of PTSD; 4) capacity to provide informed consent, and 5) telephone access. In addition, individuals were excluded with 1) a history of delirium tremens or seizures; 2) opiate use or chronic treatment with any opioid-containing medications during the previous month; 3) antabuse or naltrexone treatment (because of the pharmacological impact of these medications on alcohol cravings and use); 4) symptoms of alcohol withdrawal at initial consent; 5) acute suicidality/homicidality with intent/plan, or 6) psychosis.

Procedures

Baseline assessment

Participants learned of this study through community newspaper advertisements and flyers and were directed to contact the research coordinator. After written informed consent and initial screening for inclusion criteria, participants completed an initial baseline assessment consisting of an interview and self-report measures. Participants were also instructed in procedures for telephone daily Interactive Voice Response (IVR) and the accompanying pager system. For completing the baseline assessment, participants were compensated $30. Study procedures were approved by the [masked institution] Human Subjects Division Internal Review Board.

Daily monitoring assessment

Following the baseline assessment, participants completed daily assessments of alcohol use and distress regarding the previous day. IVR compliance was automatically tracked by the IVR system created and maintained by Database Systems Corp. Participants who failed to call were contacted within two working days to collect the data verbally. Thus, there could have been up to 4 days between the target day and actual data collection if calls were missed on Thursdays; 10% of calls were collected verbally. Participants were compensated $1 for every day of completed daily monitoring, with an additional $10 for completing 7 consecutive days of monitoring or $7 for 6 days of monitoring. The daily monitoring assessments completed during the interval between the baseline assessment and randomization to a brief behavioral intervention are the focus of the current study. The interval between baseline and receipt of the intervention was targeted to be 7 days long but varied in length from 6 to 20 days.

Measures

Screening assessment

Alcohol-related medical history and safety

Exclusion criteria were assessed using a structured interview. Suicidality was assessed with the suicide section of the Hamilton Depression Inventory (HAM-D; Hamilton, 1960).

Mental health diagnoses

The “Substance Use Disorder” and “Psychotic and Associated Symptoms” sections of the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders (SCID-1; First, Gibbon, Spitzer, & Williams, 1995) were administered to assess diagnosis of alcohol dependence, opioid abuse or dependence, schizophrenia, schizoaffective, or schizophreniform disorder. The SCID-1 is a widely used structured interview that assesses psychiatric history with good psychometric properties. To assess for past-month PTSD diagnostic status, we administered the PTSD Symptom Scale-Interview Version (PSS-I; Foa, Riggs, Danu, & Rothbaum, 1993). The PSS-I is a 17-item semi-structured interview with good internal consistency, item-total correlations, and concurrent and convergent validity (Foa et al., 1993).

Substance use

The Form-42 was adapted from the Form-90 (Miller & Del Boca, 1994) to assess alcohol use and treatment for 6-weeks prior to baseline. It was used to characterize the sample and ensure that participants had used alcohol in the previous two weeks.

Baseline assessment

PTSD symptoms

PTSD symptoms were assessed with the PTSD Checklist-Civilian Version (PCL-C; Weathers & Ford, 1996), a 17-item questionnaire assessing DSM-IV symptoms of PTSD. Participants rated how much they were bothered in the past month by each symptom on 5-point scales ranging from “not at all” to “extremely.” The PCL-C had good internal reliability in the current sample (α = 0.88).

Drinking motives

Drinking motives were assesssed with the Drinking Motives Questionnaire – Revised (DMQ-R; Cooper, 1994; Cooper, Frone, Russell, & Mudar, 1995). The DMQ-R consists of 20 items assessing four distinct drinking motives for alcohol use identified in Cooper’s (1994) model. The average score of the following 5-item subscales was used for the current study: coping (drinking to alleviate negative emotions), enhancement (drinking to achieve a pleasant feeling and for alcohol effects; i.e., “to get high,” “like the feeling”), social (e.g., drink to obtain social rewards), and conformity (e.g., drink to avoid social consequences). The DMQ-R demonstrated adequate internal reliability for the subscales in the current sample (α's coping: 0.78, enhancement: 0.72, social: 0.90, conformity: 0.88).

Daily IVR telephone monitoring assessment

Alcohol use

Participants indicated the number of standard drinks of beer, wine, and liquor consumed, each queried separately. Number of standard drinks for each beverage type was added together for total drinks per day.

PTSD symptoms

Twelve items were adapted from the PCL-C. Items were chosen to include those that typically loaded most strongly in factor analytic studies of PTSD (e.g., King, Leskin, King, & Weathers, 1998; Krause, Kaltman, Goodman, & Dutton, 2007; Palmieri, Weathers, Difede, & King, 2007), and were likely to vary daily. Items included three re-experiencing symptoms, two avoidance symptoms, three emotional numbing symptoms, and four hyperarousal symptoms. Participants indicated how bothered they were during the previous day by each symptom on 9-point scales ranging from 0 = not at all to 8 = all the time. Items were averaged to create an overall daily severity score. The internal reliability was examined for the current sample using within person averages of the daily responses to each item (α = .94).

Data Analytic Approach

Generalized estimating equations (GEE; Hardin & Hilbe, 2003) were used to analyze multilevel models given the nested nature of the data (i.e., daily reports of alcohol consumption and PTSD symptoms were nested within individual). Although GEE models allow missing data to be included in the analyses, there was relatively little missing data (i.e., only 4.7% of the possible days were missing). If a participant provided data on a given day, less than 1% of the possible responses were missing. Because of this low percentage of missing data, and that missing days may have been due to variables included in the model (e.g., alcohol use, PTSD symptoms), the maximum likelihood estimation procedures used were likely sufficient to handle potential problems related to missing data (Allison, 2009). A normal distribution with an identity link function was used for models predicting PTSD symptoms. Alcohol use is a positively skewed count variable (i.e., number of drinks per day); therefore, models predicting alcohol use were estimated using a negative binomial distribution with a log link function. GEEs with a negative binomial distribution provide incidence rate ratios (IRRs), which serve as a standardized effect size. IRRs reflect the percentage increase in the rate of drinking as a function of PTSD symptoms, while holding all other variables in the model constant.

Four separate GEE models were run to examine the influence of PTSD symptoms on alcohol use: 1) overall PTSD symptom severity predicting alcohol use on the same day; 2) overall PTSD symptom severity predicting alcohol use on the next day; 3) drinking motives as moderators of the same-day association between PTSD symptom severity and alcohol; and 4) drinking motives as moderators of the association between PTSD symptom severity and next-day alcohol use. Next, two GEE model were conducted to examine the influence of alcohol use on same-day and next-day PTSD overall symptom severity.

In all models, we included either the person-mean centered alcohol use or PTSD symptom severity variable, a variable for gender (0 = male and 1 = female), an indicator variable for weekend versus weekday (0 = weekday and 1 = weekend), and a person-mean centered monitoring day variable to test and control for changes in alcohol use or PTSD symptoms associated with potential measurement reactivity throughout the assessment period. We next examined whether other potential covariates were associated with drinking or PTSD for inclusion in the models, such as race/ethnicity, age, marital status, and employment status. Race/ethnicity, age, and employment status were not significantly associated with drinking; however, single participants drank more than married participants (b = −1.07, p < .001). Race/ethnicity, age, and marital status were not significantly associated with PTSD symptom severity, however, participants who were unemployed reported greater PTSD symptoms than those who were employed (b = −0.91, p < .05). Therefore, we included a variable to control for marital status (0 = currently single and 1 = currently married) in models predicting alcohol consumption and employment status (0 = unemployed and 1 = employed) in models predicting PTSD symptom severity. All between persons variables (the four drinking motives) were centered at the grand mean. Analyses were conducted in Stata 11.2 (StataCorp, 2009).

Results

Preliminary Analyses

Differences on demographic and key baseline variables between those included versus excluded from the analyses were examined. Chi-square analyses revealed no significant differences between the two groups on gender or race/ethnicity, p’s > .22. Univariate ANOVAs revealed no significant differences on baseline alcohol use and PTSD symptom severity between those included versus excluded from analyses, p’s > .58.

Participants were excluded from analyses if they provided data for less than 50% of their possible monitoring days. Of the remaining participants (n = 86), the individualized monitoring periods ranged from a possible 4 to 16 (M = 7.3; SD = 2.6) days. There were a possible 659 days for the daily monitoring period, and data were provided for 628 (95.3%) of those days. The majority of the sample (n = 67; 77.9%) provided data for all possible days of their monitoring period, whereas 16.3% (n = 14) missed one day, 2.3% (n = 3) missed two days, and 3.5% (n = 3) missed 3 or more days.

Means and standard deviations for baseline PTSD symptoms and alcohol consumption, as well as aggregate information from the daily monitoring period and bivariate correlations among study variables, are presented in Table 2. Participants consumed on average 4.0 (SD = 6.5) drinks per day overall and an average of 7.1 (SD = 7.3) drinks per drinking day. Additionally, participants’ reports of baseline levels of PTSD severity (i.e., PCL-C scores) were significantly correlated with daily reports of PTSD symptoms (r = .56, p < .001), as were baseline and daily reports of alcohol consumption (r = .38, p < .001).

Table 2.

Means, Standard Deviations, and Bivariate Correlations for all Study Variables

| Range | Mean | SD | 1. | 2. | 3. | 4. | 5. | 6. | 7. | 8. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Baseline PCL total score | 25 – 77 | 56.1 | 12.1 | -- | |||||||

| 2. Baseline Form-42 average drinks per day |

0 – 28 | 6.8 | 5.6 | .30*** | -- | ||||||

| 3. IVR average number of drinks per day |

0 – 54 | 4.0 | 6.5 | .13*** | .38*** | -- | |||||

| 4. IVR average of all PTSD symptoms per day |

0 – 8 | 3.7 | 1.8 | .21*** | .16*** | .20*** | -- | ||||

| Drinking motives | |||||||||||

| 5. Coping | 0 – 5 | 3.4 | 1.0 | .34*** | .29*** | .16*** | .20*** | -- | |||

| 6. Enhancement | 0 – 5 | 3.2 | 1.0 | .39*** | .30*** | .16*** | .11** | .42*** | -- | ||

| 7. Social | 0 – 5 | 2.8 | 1.4 | .09*** | .25*** | .01 | .24*** | .37*** | .38*** | -- | |

| 8. Conformity | 0 – 5 | 1.4 | 1.1 | .28*** | .23*** | .01 | .24*** | .47*** | .38*** | .60*** | -- |

Note. SD = standard deviation;

PCL = PTSD Checklist;

PTSD = posttraumatic stress disorder.

Examining the Self-Medication Hypothesis

First, we conducted GEE models to examine whether PTSD symptom severity was associated with same-day (Model 1, Table 3) and next-day (Model 2, Table 3) drinking. In Model 1, a 1-unit increase in PTSD symptom severity was associated with a 20% increased rate of alcohol use on the same day. In Model 2, we also found that a 1-unit increase in PTSD symptom severity was associated with a 7% increase in alcohol use on the next day. Additionally, alcohol use was higher among men, differed as a function of weekend versus weekday, and was lower among those who were married compared to currently single participants.

Table 3.

Overall PTSD Symptom Severity Predicting Same-Day and Next-Day Number of Drinks

| Model 1 | Model 2 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Same-Day Alcohol Use | Next-Day Alcohol Use | |||

|

| ||||

| Variable | b | IRR [95% C.I.] | b | IRR [95% C.I.] |

| Female gender | −0.70*** | 0.50 [0.38, 0.65] | −0.80*** | 0.45 [0.34, 0.59] |

| Married | −1.05*** | 0.35 [0.22, 0.54] | −0 78*** | 0.46 [0.29, 0.72] |

| Monitoring day | 0.04 | 1.04 [0.99, 1.08] | −0.01 | 0.99 [0.95, 1.05] |

| Weekend | 0.26** | 1.29 [1.07, 1.57] | 0.26* | 1.30 [1.05, 1.60] |

| Overall PTSD severity | 0.19*** | 1.20 [1.13, 1.28] | 0.08* | 1.08 [1.01, 1.16] |

Note. IRR = incidence rate ratio; C.I. = confidence interval; monitoring day (range 1-16). PTSD = posttraumatic stress disorder.

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .001.

Examining the Mutual Maintenance Hypothesis

Two GEE models were conducted to examine whether drinking predicted same-day (Model 3, Table 4) and next-day (Model 3, Table 4) PTSD symptoms. In Model 3, greater drinking was associated with more PTSD symptoms that same day. Holding all other variables in the model constant, a 1-unit increase in the number of standard drinks was associated with a relative increase in PTSD symptoms of .02 units. However, drinking was not associated with next-day PTSD symptoms (Model 4, Table 4). Gender, monitoring day, and weekend versus weekday were not significantly associated with either same-day or next-day PTSD symptoms.

Table 4.

Daily Drinking Predicting Next-Day Overall PTSD Symptom Severity

| Model 3 | Model 4 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Same-Day PTSD | Next-Day PTSD | |||

|

| ||||

| Variable | b | 95% C.I. | b | 95% C.I. |

| Female gender | −0.26 | −0.81,0.29 | −0.49 | −1.10,0.11 |

| Employed | −0.86* | −1.67, −0.03 | −0.81 | −1.72, 0.10 |

| Monitoring day | −0.06 | −0.12, 0.01 | −0.05 | −0.13, 0.03 |

| Weekend | −0.11 | −0.31, 0.10 | −0.01 | −0.23, 0.20 |

| Daily drinking | 0.02* | 0.01, 0.04 | 0.01 | −0.01, 0.03 |

Note. C.I. = confidence interval; monitoring day (range 1-16). PTSD = posttraumatic stress disorder.

p < .05.

** p < .01. *** p < .001.

The Moderating Effects of Drinking Motives

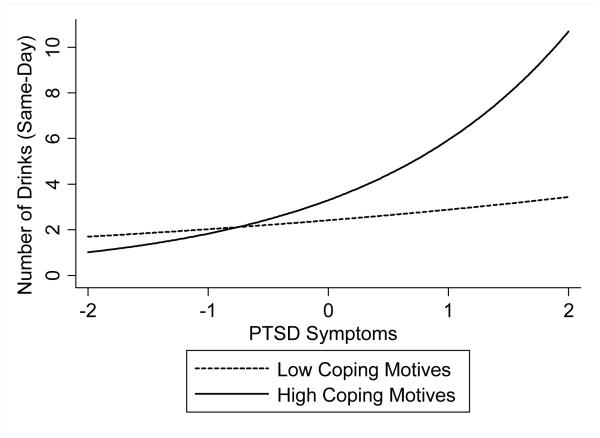

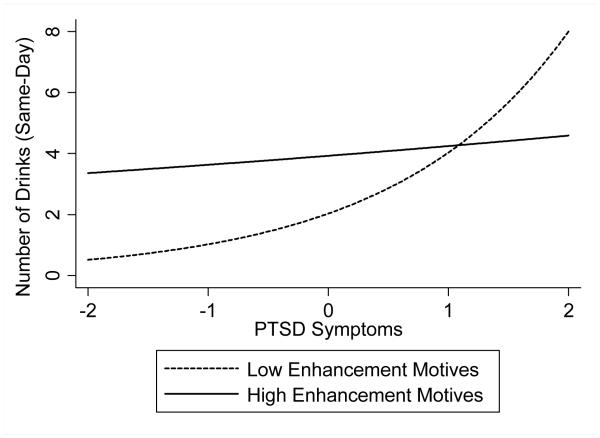

Next, GEE models were used to examine drinking motives as moderators of the association between PTSD and both same-day (Model 5, Table 5) and next-day (Model 6, Table 5) alcohol consumption in which all drinking motives were included in the same model. As shown in Model 5, there were significant interactions between PTSD symptom severity and both coping motives and enhancement motives in predicting same-day drinking; social motives and conformity motives did not significantly interact with PTSD severity in predicting same-day drinking. With regard to coping motives, the results indicated that as PTSD symptoms increased, drinking increased at a greater rate among those with higher coping motives than those with lower coping motives (Figure 1). Specifically, for every 1-unit increase in PTSD symptom severity, same-day drinking increased by a rate of 37% for those high in coping motives (i.e., 1 standard deviation above the mean) and only 10% for those low in coping motives (i.e., 1 standard deviation below the mean). For individuals with high enhancement motives (i.e., 1 standard deviation above the mean), drinking was steady, only increasing at a rate of 4% for every 1-unit increase in PTSD symptom severity. Whereas among those with low enhancement motives (i.e., 1 standard deviation below the mean), alcohol consumption increased by a rate of 45% as PTSD symptom severity increased by 1-unit (Figure 2). There were no significant interactions between PTSD symptom severity and any of the drinking motives predicting next-day alcohol use (Model 6). Please see Footnote1 for results of the alternate analytic strategy of treating the moderating effects of each drinking motive in separate models.

Table 5.

Examining Drinking Motives as Moderators of PTSD Symptom Severity on Same-Day and Next-Day Number of Drinks

| Model 5 | Model 6 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Same-Day Alcohol Use | Next-Day Alcohol Use | |||

| Variable | b | IRR [95% CI] | b | IRR [95% CI] |

| Female gender | −0.69*** | 0.50 [0.37, 0.68] | −0.72*** | 0.48 [0.35, 0.67] |

| Married | −1.09*** | 0.34 [0.21, 0.54] | −0.82** | 0.44 [0.27, 0.72] |

| Monitoring day | 0.02 | 1.02 [0.97, 1.07] | −0.01 | 0.99 [0.93, 1.05] |

| Weekend | 0.25* | 1.29 [1.05, 1.57] | 0.19 | 1.21 [0.97, 1.50] |

| Overall PTSD severity | 0.21*** | 1.23 [1.14, 1.32] | 0.07 | 1.07 [0.98, 1.16] |

| Coping motives | −0.25 | 0.78 [0.52, 1.18] | 0.32 | 1.38 [0.87, 2.19] |

| Enhancement motives | 0.93*** | 2.53 [1.69, 3.79] | 0.38 | 1.46 [0.95, 2.26] |

| Social motives | −0.21 | 0.81 [0.61, 1.08] | −0.03 | 0.97 [0.71, 1.33] |

| Conformity motives | −0.18 | 0.84 [0.57, 1.23] | −0.33 | 0.72 [0.47, 1.09] |

| PTSD × coping | 0.11* | 1.12 [1.02, 1.23] | 0.01 | 1.01 [0.90, 1.12] |

| PTSD × enhancement | −0.16*** | 0.85 [0.78, 0.92] | −0.04 | 0.96 [0.88, 1.05] |

| PTSD × social | 0.05 | 1.05 [0.99, 1.11] | 0.00 | 1.00 [0.94, 1.07] |

| PTSD × conformity | 0.01 | 1.01 [0.93, 1.10] | 0.05 | 1.05 [0.96, 1.15] |

Note. IRR = incidence rate ratio; C.I. = confidence interval; monitoring day (range 1-16). PTSD = posttraumatic stress disorder.

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .001.

Figure 1.

The interaction between daily PTSD symptoms and coping drinking motives predicts the number of standard drinks consumed on the same day. For illustrative purposes, estimates are shown for men on a weekend (i.e., when drinking was likely to be heavy).

Figure 2.

The interaction between daily PTSD symptoms and enhancement drinking motives predicts the number of standard drinks consumed on the same day. For illustrative purposes, estimates are shown for men on a weekend (i.e., when drinking was likely to be heavy).

Discussion

This paper is the first to evaluate the self-medication and the mutual maintenance models using daily measures of PTSD symptoms and drinking behavior in a clinical sample with comorbid PTSD and AD. Thus, our prospective daily monitoring methodological approach augments previous research, providing a more nuanced evaluation of the relationship between PTSD symptoms and alcohol consumption in close to real time. Using a daily monitoring protocol, we found that on days with higher PTSD symptoms relative to one’s average level, treatment seeking individuals with comorbid PTSD and AD also drank more that day and the next day. Specifically, for every 1-unit increase in PTSD symptom severity there was a corresponding 20% increase in drinking the same day and a 7% increase the following day. These findings indicate that even modest increases in PTSD symptom severity relative to one’s average are associated with large increases in drinking the same day and smaller, but still substantial increases in drinking the next day. It is interesting to note that although this pattern of results is generally in keeping with the hypothesized self-medication model, there does seem to be lingering effects of PTSD on next day drinking, suggesting that the same-day drinking may not have entirely mitigated that day’s PTSD symptom exacerbation. In other words, if alcohol consumption is indeed increased in an attempt to self-medicate PTSD symptomatology, these results would suggest that it is not entirely successful since elevated drinking associated with the previous day’s PTSD exacerbation is apparent the next day. Future research that includes assessment of the perceived success of symptom mitigation by drinking could help tease out this issue.

We also found some support for the mutual maintenance model in that the amount of alcohol consumed on a given day was modestly associated with same-day PTSD symptom severity, though drinking did not predict next-day PTSD symptom severity. These results are not as robust as those we found in support of the self-medication model. They suggest that factors other than alcohol consumption are stronger determinants of variation in PTSD symptom severity day-to-day and that drinking does not serve a strong role in maintaining PTSD symptomatology. Consistent with this finding, early work by Brown and colleagues (1998) found that individuals with comorbid PTSD and AD were of the opinion that increases in their PTSD symptoms led to increases in their drinking, but that their drinking did not increase their PTSD and instead, mitigated it. In contrast, Kaysen and colleagues (2006) found that while women with recent trauma exposure who were problem drinkers prior to the trauma reported lower PTSD symptom severity initially than did moderate drinkers and abstainers, these women failed to recover at the same rate as non-heavy drinkers and remained more symptomatic with regard to their PTSD. It is possible that in the immediate aftermath of trauma, heavy drinking interferes with natural recovery, thereby helping to maintain elevated PTSD symptomatology that might otherwise resolve. Over time the relationship between the two phenomena may shift such that once both disorders are established, PTSD may be more likely to drive drinking than vice versa.

An additional observation that, although not surprising, is worth noting is that PTSD and drinking had different significant covariates. Alcohol consumption was found to be significantly associated with male gender, weekend versus weekday use, and currently being single. In contrast, gender and day of the week were not associated with PTSD symptom severity while those who were unemployed reported greater daily PTSD symptom severity. These differences underscore the extent to which the two symptom processes are likely complexly determined and that each may have unique determinants and constraints.

Drinking Motives’ Influence on the Relationship between PTSD and Drinking

This is also the first study to examine whether drinking motives moderate the day-to-day relationship between PTSD symptoms and drinking behavior. An initial observation is that both enhancement and coping motives were highly endorsed, suggesting that even in this comorbid sample, drinking motives other than coping are salient and may be important to address clinically and conceptually. When considered simultaneously in the same model, both coping and enhancement drinking motives were significant moderators of the same-day PTSD and drinking relationship, suggesting that PTSD/alcohol relationships may be more or less salient depending on individual motivations for drinking. For those higher on coping drinking motives, a 1-unit increase in PTSD symptom severity was associated with a 37% increase in amount of alcohol consumed while among those low on coping drinking motives, a 1-unit PTSD increase was only associated with a 10% increase in alcohol consumption. It is noteworthy that even among individuals dually diagnosed with PTSD and AD, relative changes in PTSD symptom severity do not appear to function as an especially strong drinking cue for those who are not motivated to cope with negative affect by drinking alcohol. Future studies in this area should include assessment of perceived effects of drinking on symptom mitigation to extend the current findings on motives for drinking and better explain individual differences in both drinking motives and drinking behavior. In addition, in light of previous research that has found that those high on coping drinking motives are likely to report greater incidence of harmful consequences of drinking (Goldstein, Flett, & Wekerle, 2010; Read, Wood, Kahler, Maddock, & Palfai, 2003; Yusko, Buckman, White, & Pandina, 2008), future research should evaluate whether this is the case among those with comorbid PTSD/AD as there may be a subset of people in this group who are especially vulnerable and in need of particularly careful clinical monitoring.

We also found that among individuals with high enhancement motives (i.e., after partialing out common variance from the other drinking motives), drinking was steady regardless of PTSD symptom severity that day, whereas among those with low enhancement motives, alcohol consumption increased as PTSD symptoms increased from one’s average level. For those high on enhancement drinking motives, a 1-unit increase in PTSD severity was associated with only a 4% increase in alcohol consumption, while for those low on enhancement drinking motives, a 1-unit increase in PTSD was associated with a 45% increase in same day drinking. Thus, among individuals with both PTSD and AD, individuals high on enhancement motives did not appear to drink in response to their PTSD symptom severity. These individuals drank similar amounts of alcohol regardless of their PTSD symptom levels and thus did not appear to self-medicate PTSD symptoms with alcohol. We did not find an effect for social or conformity models, which lends credence to the specificity of coping and enhancement motives in relation to the PTSD and drinking relationships. In addition, we did not find that any drinking motives moderated the relationship between PTSD and next-day drinking. This may be due to the fact that there was a relatively modest relationship between PTSD and next-day drinking, so the ability of drinking motives to explain any appreciable variance in this relationship was diminished.

An important limitation to acknowledge was the relatively brief monitoring period, which impacted our ability to evaluate different lagged associations between these variables. Using daily data collected over a longer period of time, it would be interesting to evaluate whether there is a cumulative effect of PTSD on drinking such that sustained PTSD elevations lead to greater drinking at the end of some interval (e.g., after five weekdays), and whether such a pattern is especially germane for different subsets of individuals (e.g., employed vs. unemployed). Additionally, multiple assessment intervals within days might be even more useful in evaluating how PTSD and drinking are temporally related. Because we did not assess PTSD symptoms and drinking multiple times within each day, we cannot say with any certainty that PTSD symptom severity is causally related to amount of drinking within the same day. Thus, future studies would benefit from a longer assessment period that involves multiple within-day measurements.

Although the ideal time lag to evaluate the relationship between PTSD and alcohol use is not currently known, important information may still be gleaned from the single day lag examined in this study. From a clinical perspective, as is consistent with the present results, if someone has had a PTSD exacerbation we might expect to see the strongest association between PTSD symptoms and drinking within that same day, but there could be carry over from one day to the next regarding their drinking. Such a scenario has significant clinical implications in that not only do vulnerable clients need to have coping strategies for dealing with PTSD exacerbations without drinking on the same day, but the use of proactive coping strategies may be critical to sustain abstinence the next day. Similarly, although we did not find support for the mutual maintenance model in the one-day lag model, a plausible rationale for testing it with this lag is that it is reasonable to think that more drinking on a given day could exacerbate PTSD symptoms the next day, perhaps related to withdrawal and other physical alcohol effects associated with heavy drinking (e.g., increased irritability, poor sleep quality) or greater social or intra-personal consequences (e.g., detachment from others, feeling guilt or shame).

The current study has several other limitations, including the clinical severity of the sample, both in terms of PTSD chronicity and alcohol diagnostic severity. Moreover, this sample was seeking treatment and expressed interest in reducing or quitting drinking. Although these findings may inform us about how PTSD and drinking influence each other in close to real time for those with concurrent PTSD/AD, they do not tell us about the establishment of problem drinking in response to trauma exposure and initial PTSD symptoms. Our results also may not generalize to those experiencing lower degrees of difficulty or to those not seeking to change their drinking. We also did not assess personality factors such as impulsivity or neuroticism at baseline (Miller et al., 2006), and therefore cannot speak to whether either or both PTSD or drinking behavior might be better explained by a “third variable.” In addition, we did not assess all PTSD symptoms each day, which could have missed symptoms that make a significant difference in understanding drinking at the daily level. We did attempt to exclude only symptoms that seemed unlikely to vary at the daily level (e.g., foreshortened sense of the future) but there are insufficient daily level studies of PTSD symptoms available to know more definitively which ones are unlikely to vary from day to day.

It is also possible that reporting on PTSD symptoms for the previous day rather than at a given moment in time as might be captured in an ecological momentary assessment (EMA) protocol may have introduced self-report bias. However, the field routinely takes at face value patients’ reports of their PTSD symptoms over month long intervals, and we are unaware of research investigating the correspondence between daily monitoring and EMA protocols for PTSD symptoms. A recent study has found very good correspondence between daily diary and retrospective recall for PTSD symptoms (Naragon-Gainey, Simpson, Moore, Varra, & Kaysen, 2012). Although we cannot be certain that reporting on one’s PTSD symptoms for the previous day yields accurate information, we have no reason to expect that it would be any less accurate than what is typically obtained in standard PTSD assessments. Also, it is possible that obtaining ratings of symptoms from the day before could be more accurate than attempting to obtain ratings in the moment (i.e., EMA sampling) given the nature of PTSD (e.g., people are unlikely to be able to provide ratings while experiencing flashbacks or related dissociative symptoms or to rate their avoidance accurately because rating it in the moment would necessarily change it).

It is also important to acknowledge that repeated retrospective data collection of PTSD symptoms and drinking behavior may introduce some bias. It is possible that participants could have attributed their drinking behavior to their elevated PTSD symptom scores and then responded in a manner consistent with this belief. This concern would be mitigated, although not completely eliminated, by collecting data multiple times a day. Unfortunately there is likely not a way to obtain completely bias free reports of these types of behaviors because even if the respondents do not initially think there is a relationship between two (or more) phenomenon, simply being asked about them repeatedly could introduce bias through demand characteristics.

Despite these limitations, there are several clinical implications of the study’s findings. Results indicate that self-medication of PTSD symptoms may be a factor associated with the day-to-day maintenance of problematic drinking among individuals who meet diagnostic criteria for both disorders, and particularly for those high on coping drinking motives and those low on enhancement drinking motives. Clinicians could profitably work with clients to develop alternative means of coping with PTSD symptoms without resorting to drinking. Use of skills such as distress tolerance and mindfulness may be particularly helpful in addressing these symptoms for clients with comorbid AD. When using cognitive interventions to treat drinking or PTSD symptoms, directly addressing cognitive distortions regarding the utility of alcohol to enhance positive affect or decrease negative emotional experiences may be helpful as well. It may also be useful to work with clients high on enhancement drinking motives to generate alternative strategies that do not involve drinking to enhance positive emotional states.

In conclusion, the current study examined daily associations between PTSD symptoms and alcohol use in a sample of men and women with comorbid PTSD and AD. Results indicated some support for the mutual maintenance model in that drinking was modestly associated with same day PTSD symptom severity, though not with next day symptom severity. Stronger support was found for the self-medication model in that greater PTSD symptom severity from one’s average level were positively associated with greater same-day drinking and with next-day drinking. These associations were moderated by drinking motives: after controlling for the effects of the other drinking motives, greater coping motives were associated with greater alcohol use in response to relative increases in PTSD symptoms on the same day compared to lower coping motives. Moreover, after controlling for the effects of the other drinking motives, higher enhancement motives were associated with steady alcohol use regardless of PTSD symptom severity, while lower enhancement motives were associated with greater alcohol use on days when greater PTSD symptoms were reported. Taken together, these findings provide further support for the self-medication model, but they also highlight the potential contribution of drinking motives in developing a more nuanced conceptualization of self-medication, which could be especially useful in tailoring individual intervention strategies. Future research that examines the interplay between PTSD symptoms and drinking behavior, and other potential moderators of this relationship (e.g., order of onset of the two disorders, family history of AUD, trauma cognitions, personality factors, perceived effects of alcohol) using innovative methodologies, will further our understanding of how PTSD and AD manifest together and influence one another.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported in part by a grant from NIH/NIAAA #1 R21 AA 17130-01 and by resources from the VA Puget Sound Health Care System.

Footnotes

When we entered each drinking motive into a separate model we found different results for the association between PTSD severity and same-day drinking, but not for the models predicting next-day drinking in which there were no significant moderation effects when the drinking motives were entered simultaneously or independently. When entered independently, enhancement motives significantly interacted with PTSD symptom severity to predict same-day drinking; however, the pattern of findings was slightly different. Drinking increased with relative increases in PTSD symptom severity for individuals both low and high in enhancement motives; however, those with high enhancement motives increased at a slightly lower rate. Unlike when all motives were included in the same model, coping motives did not significantly moderate the association between PTSD and same-day drinking when examined independently. And similar to the model in which all motives were entered simultaneously, social and conformity drinking motives did not independently moderate the association between PTSD symptoms and same-day drinking. Given these differences, it is important to interpret the moderation effects of coping and enhancement motives when all motives are included in the same model as occurring after partialing out the common variance shared among all drinking motives.

References

- Allison PD. Missing data. In: Millsap RE, Maydeu-Olivares A, editors. The SAGE Handbook of Quantitative Methods in Psychology. SAGE Publications Inc; Thousand Oaks, CA: 2009. pp. 72–89. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association . Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 4th Author; Washington DC: 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Armelli S, Conner TS, Cullum J, Tennen H. A longitudinal analysis of drinking motives moderating the negative affect-drinking association among college students. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2010;24:38–47. doi: 10.1037/a0017530. doi:10.1037/a0017530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker TB, Piper ME, Fiore MC, McCarthy DE, Majeskie MR. Addiction motivation reformulated: An affective processing model of negative reinforcement. Psychological Review, 2004;111:33–51. doi: 10.1037/0033-295X.111.1.33. doi:10.1037/0033-295X.111.1.33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Begle A,M, Hanson RF, Danielson CK, McCart MR, Ruggiero KJ, Amstadter AB, Kilpatrick DG. Longitudinal pathways of victimization, substance use, and delinquency: Findings from the National Survey of Adolescents. Addictive Behaviors, 2011;36:682–689. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2010.12.026. doi:10.1016/j.addbeh.2010.12.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown PJ, Stout RL, Gannon-Rowley J. Substance use disorder-PTSD comorbidity. Patients' perceptions of symptom interplay and treatment issues. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 1998;15:445–448. doi: 10.1016/s0740-5472(97)00286-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cerda M, Tracy M, Galea S. A prospective population based study of changes in alcohol use and binge drinking after a mass traumatic event. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 2011;115:1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2010.09.011. doi:10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2010.09.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cleveland H, Harris KS. The role of coping in moderating within-day associations between negative triggers and substance use cravings: A daily diary investigation. Addictive Behaviors, 2010;35:60–63. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2009.08.010. doi:10.1016/j.addbeh.2009.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coffey SF, Schumacher JA, Stasiewicz PR, Henslee AM, Baillie LE, Landy N. Craving and physiological reactivity to trauma and alcohol cues in posttraumatic stress disorder and alcohol dependence. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology. 2010;18(4):340–349. doi: 10.1037/a0019790. doi:10.1037/a0019790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper M. Motivations for alcohol use among adolescents: Development and validation of a four-factor model. Psychological Assessment, 1994;6:117–128. doi:10.1037/1040-3590.6.2.117. [Google Scholar]

- Cooper M, Frone M, Russell M, Mudar P. Drinking to regulate positive and negative emotions: A motivational model of alcohol use. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1995;69(5):990–1005. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.69.5.990. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.69.5.990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dixon LJ, Leen-Feldner EW, Ham LS, Feldner MT, Lewis SF. Alcohol use motives among traumatic event-exposed, treatment-seeking adolescents: Associations with posttraumatic stress. Addictive Behaviors, 2009;34:1065–1068. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2009.06.008. doi:10.1016/j.addbeh.2009.06.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrier-Auerbach AG, Kehle SM, Erbes CR, Arbisi PA, Thuras P, Polusny MA. Predictors of alcohol use prior to deployment in National Guard soldiers. Addictive Behaviors, 2009;34:625–631. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2009.03.027. doi:10.1016/j.addbeh.2009.03.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- First MB, Gibbon M, Spitzer RL, Williams JBW. Structured clinical interview for DSM-IV (SCID) New York State Psychiatric Institute; New York: 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Foa EB, Riggs DS, Dancu CV, Rothbaum BO. Reliability and validity of a brief instrument for assessing post-traumatic stress disorder. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 1993;6:459–473. doi:10.1002/jts.2490060405. [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein AL, Flett GL, Wekerle C. Child maltreatment, alcohol use and drinking consequences among male and female college students: An examination of drinking motives as mediators. Addictive behaviors. 2010;35(6):636–639. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2010.02.002. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2010.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grayson CE, Nolen-Hoeksema S. Motives to drink as mediators between childhood sexual assault and alcohol problems in adult women. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 2005;18:137–145. doi: 10.1002/jts.20021. doi.10.1002/jts.20021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haller M, Chassin L. The Influence of PTSD Symptoms on Alcohol and Drug Problems: Internalizing and Externalizing Pathways. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 2012;25:691–699. doi: 10.1002/jts.21751. doi:10.1002/jts.21751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton M. A rating scale for depression. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery and Psychiatry. 1960;23:56–62. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.23.1.56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardin JW, Hilbe JM. Generalized Estimating Equations. Chapman & Hall/CRC; Boca Raton, FL: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Hasin DS, Stinson FS, Ogburn E, Grant BF. Prevalence, correlates, disability, and comorbidity of DSM-IV alcohol abuse and dependence in the United States: Results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2007;64(7):830–842. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.64.7.830. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.64.7.830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hien DA, Jiang H, Campbell AN, Hu M, Miele GM, Cohen LR, Nunes EV. Do treatment improvements in PTSD severity affect substance use outcomes? A secondary analysis from a randomized clinical trial in NIDA’s Clinical Trials Network. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2010;167(1):95–101. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2009.09091261. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.2009.09091261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hofmann SG, Litz BT, Weathers FW. Social anxiety, depression, and PTSD in Vietnam veterans. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 2003;17:573–582. doi: 10.1016/s0887-6185(02)00227-x. doi: 10.1016/S0887-6185(02)00227-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hruska B, Fallon W, Spoonster E, Sledjeski EM, Delahanty DL. Alcohol Use Disorder history moderates the relationship between avoidance coping and posttraumatic stress symptoms. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 2011;25:405–414. doi: 10.1037/a0022439. doi: 10.1037/a0022439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaysen D, Atkins DC, Moore SA, Lindgren KP, Dillworth T, Simpson T. Alcohol use, problems, and the course of Posttraumatic Stress Disorder: A prospective study of female crime victims. Journal of Dual Diagnosis. 2011;7(4):262–279. doi: 10.1080/15504263.2011.620449. doi:10.1080/15504263.2011.620449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaysen D, Atkins D, Simpson T, Stappenbeck C, Blayney J, Lee CM, Larimer ME. Proximal relationships between PTSD symptoms and drinking among female college students: Results from a Daily Monitoring Study. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2013 Aug 5; doi: 10.1037/a0033588. Advance online publication. doi:10.1037/a0033588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaysen D, Dillworth TM, Simpson T, Waldrop A, Larimer ME, Resick PA. Domestic violence and alcohol use: Trauma-related symptoms and motives for drinking. Addictive Behaviors, 2007;32:1272–1283. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2006.09.007. doi:10.1016/j.addbeh.2006.09.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaysen D, Simpson T, Dillworth T, Gunter C, Larimer ME, Resick P. Alcohol problems and Posttraumatic Stress Disorder in female crime victims. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2006;19(3):399–403. doi: 10.1002/jts.20122. doi:10.1002/jts.20122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Berglund P, Demler O, Jin R, Merikangas KR, Walters EE. Lifetime prevalence and age-of-onset distributions of DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2005;62:593–602. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.6.593. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.6.593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Crum RM, Warner LA, Nelson CB, Schulenberg J, Anthony JC. Lifetime co-occurrence of DSM-III-R alcohol abuse and dependence with other psychiatric disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey. Archives of General Psychiatry, 1997;54:313–321. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1997.01830160031005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khantzian EJ. The self-medication hypothesis revisited: The dually diagnosed patient. Primary Psychiatry. 2003;10(9):47–54. [Google Scholar]

- King DW, Leskin GA, King LA, Weathers FW. Confirmatory factor analysis of the Clinician-Administered PTSD Scale: Evidence of the dimensionality of posttraumatic stress disorder. Psychological Assessment. 1998;10:90–96. doi:10.1037/1040-3590.10.2.90. [Google Scholar]

- Krause ED, Kaltman S, Goodman LA, Dutton M. Longitudinal factor structure of posttraumatic stress symptoms related to intimate partner violence. Psychological Assessment. 2007;19(2):165–175. doi: 10.1037/1040-3590.19.2.165. doi:10.1037/1040-3590.19.2.165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leeise M, Pagura J, Sareen J, Bolton JM. The use of alcohol and drugs to selfmedicate symptoms of Posttraumatic Stress Disorder. Depression and Anxiety, 2010;27:731–736. doi: 10.1002/da.20677. doi:10.1002/da.20677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leigh B. Using daily reports to measure drinking and drinking patterns. Journal of Substance Abuse. 2000;12(1-2):51–65. doi: 10.1016/s0899-3289(00)00040-7. doi:10.1016/S0899-3289(00)00040-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marshall BD, Prescott MR, Liberzon I, Tamburrino MB, Calabrese JR, Galea S. Coincident posttraumatic stress disorder and depression predict alcohol abuse during and after deployment among Army National Guard soldiers. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2012;124(3):193–199. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2011.12.027. doi:10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2011.12.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McFarlane AC, Browne D, Bryant RA, O’Donnell M, Silove D, Creamer M, Horsley K. A longitudinal analysis of alcohol consumption and the risk of posttraumatic symptoms. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2009;118:166–172. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2009.01.017. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2009.01.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller WR, Del Boca FK. Measurement of drinking behavior using the Form 90 family of instruments. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1994;12:112–118. doi: 10.15288/jsas.1994.s12.112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller MW, Vogt DS, Mozley SL, Kaloupek DG, Keane TM. PTSD and substance-related problems: The mediating roles of disconstraint and negative emotionality. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2006;115:269–279. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.115.2.369. doi:10.1037/0021-843X.115.2.369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miranda R, Meyerson LA, Long PJ, Marx BP, Simpson SM. Sexual assault and alcohol use: Exploring the self-medication hypothesis. Violence And Victims. 2002;17(2):205–217. doi: 10.1891/vivi.17.2.205.33650. doi:10.1891/vivi.17.2.205.33650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Najdowski CJ, Ullman SE. Prospective effects of sexual victimization on PTSD and problem drinking. Addictive Behaviors. 2009;34:965–968. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2009.05.004. doi:10.1016/j.addbeh.2009.05.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naragon-Gainey K, Simpson T, Moore S, Varra A, Kaysen D. The correspondence of aggregate daily PTSD symptom reports and retrospectivereport: Examining the roles of symptom instability, PTSD symptom clusters, and depression symptoms. Psychological Assessment. 2012;24(4):1041–1047. doi: 10.1037/a0028518. doi:10.1037/a0028518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nugent NR, Lally MA, Brown L, Knopik VS, McGeary JE. OPRM1 and diagnosis-related posttraumatic stress disorder in binge-drinking patients living with HIV. AIDS and Behavior. 2012;16(8):2171–2180. doi: 10.1007/s10461-011-0095-8. doi:10.1007/s10461-011-0095-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oslin DW, Cary M, Slaymaker V, Colleran C, Blow FC. Daily ratings measures of alcohol craving during an inpatient stay define subtypes of alcohol addiction that predict subsequent risk for resumption of drinking. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2009;103(3):131–136. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2009.03.009. doi:10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2009.03.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ouimette P, Read JP, Wade M, Tirone V. Modeling associations between posttraumatic stress symptoms and substance use. Addictive Behaviors. 2010;35(1):64–67. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2009.08.009. doi:10.1016/j.addbeh.2009.08.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palmieri PA, Weathers FW, Difede J, King DW. Confirmatory factor analysis of the PTSD Checklist and the Clinician-Administered PTSD Scale in disaster workers exposed to the World Trade Center ground zero. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2007;116:329–341. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.116.2.329. doi:10.1037/0021-843X.116.2.329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Possemato K, Kaier E, Wade M, Lantinga LJ, Maisto SA, Ouimette P. Assessing daily fluctuations in posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms and substance use with interactive voice response technology: Protocol compliance and reactions. Psychological Services. 2012;9(2):185–196. doi: 10.1037/a0027144. doi:10.1037/a0027144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Read JP, Wood MD, Kahler CW, Maddock JE, Palfai TP. Examining the role of drinking motives in college student alcohol use and problems. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2003;17:13–23. doi: 10.1037/0893-164x.17.1.13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rehm J, Mathers C, Popova S, Thavorncharoensap M, Teerawattananon Y, Patra J. Global burden of disease and injury and economic cost attributable to alcohol use and alcohol-use disorders. The Lancet. 2009;373(9682):2223–2233. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60746-7. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60746-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sartor CE, McCutcheon VV, Pommer NE, Nelson EC, Grant JD, Duncan AE, Heath AC. Common genetic and environmental contributions to post-traumatic stress disorder and alcohol dependence in young women. Psychological Medicine. 2011;41:1497–1505. doi: 10.1017/S0033291710002072. doi:10.1017/S0033291710002072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simpson TL. Childhood sexual abuse, PTSD, and the functional roles of alcohol use among women drinkers. Substance Use & Misuse. 2003;38:249–270. doi: 10.1081/ja-120017248. doi:10.1081/JA-120017248 1082-6084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simpson TL, Stappenbeck CA, Varra AA, Moore SA, Kaysen D. Symptoms of Posttraumatic Stress Predict Craving Among Alcohol Treatment Seekers: Results of a Daily Monitoring Study. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2012 Feb 27; doi: 10.1037/a0027169. Advance online publication. doi:10.1037/a0027169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- StataCorp . Stata Statistical Software: Release 11. StataCorp LP; College Station, TX: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Testa M, Livingson JA, Hoffman JH. Does sexual victimization predict subsequent alcohol consumption? A prospective study among a community sample of women. Addictive Behaviors. 2007;32:2926–2939. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2007.05.017. doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2007.05.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Testa M, VanZile-Tamsen C, Livingston JA. Prospective prediction of women's sexual victimization by intimate and nonintimate male perpetrators. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2007;75(1):52–60. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.75.1.52. doi:10.1037/0022-006X.75.1.52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ullman SE, Filipas HH, Townsend SM, Starzynski LL. Trauma Exposure, Posttraumatic Stress Disorder and Problem Drinking in Sexual Assault Survivors. Journal Of Studies On Alcohol. 2005;66(5):610–619. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2005.66.610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weathers F, Ford J. Psychometric properties of the PTSD checklist (PCL-C, PCL-S, PCLM, PCL-PR) In: Stamm BH, editor. Measurement of stress, trauma, and adaptation. Sidran Press; Lutherville, MD: 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Wolitzky-Taylor K, Bobova L, Zinbarg RE, Mineka S, Craske MG. Longitudinal investigation of the impact of anxiety and mood disorders in adolescence on subsequent substance use disorder onset and vice versa. Addictive Behaviors. 2012;37:982–985. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2012.03.026. doi:10.1016/j.addbeh.2012.03.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yusko DA, Buckman JF, White HR, Pandina RJ. Risk for excessive alcohol use and drinking-related problems in college student athletes. Addictive Behaviors. 2008;33(12):1546–56. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2008.07.010. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2008.07.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]