Abstract

Based on a recent hypothesis, “Five same genomes of endosperm are essential for its development in Lilium”, it is expected that allotriploid lily (OTO) can be hybridized with diploid Oriental lily (OO) for introgression breeding in Lilium L.. To test the hypothesis, OTO lilies, ‘Belladonna’, ‘Candy Club’ and ‘Travatore’, were used as the maternal parents and crossed with two diploid OO cultivars, ‘Siberia’ and ‘Sorbonne’, and the species L. regale Wilson (TT). Results showed that capsules of all OTO × OO hybridizations developed well and 0.8~3.3 viable seedlings per ovary were obtained through normal pollination and embryo rescue; however, all OTO × TT crosses failed. Genomic in situ hybridization showed that the progenies of the OTO × OO hybridizations were aneuploid and a variable number of T-genome chromosomes were introduced into the progenies through the allotriploid lilies. The present results not only demonstrate that allotriploid OTO lilies, although male sterile, can be used as maternal parents to produce aneuploid progenies, but also strongly support the new hypothesis in lily breeding.

Keywords: aneuploid, endosperm genome composition, five-same-genomes, Fritillaria-type embryo sac, Lilium

Introduction

Lily (Lilium L.) is an important bulb flower worldwide. Most lily cultivars originating from intra-sectional hybridizations of the genus Lilium are classified into four groups: Asiatic (A), Longiflorum (L), Oriental (O) and Trumpet (T) (Van Tuyl et al. 2000). Hybridizations within each group are usually straightforward and their F1 hybrids are fertile, however, those between different groups need cut-style pollination and embryo rescue, and such distant F1 hybrids are highly sterile (McRae 1998, Van Tuyl et al. 1988, 1991, 2002a, 2002b, Zhou et al. 2008b). Notwithstanding, these distant F1 hybrids can spontaneously or artificially produce 2n-gametes and result in sexual polyploidization (Barba-Gonzalez et al. 2004, 2005a, 2005b, 2006, Khan et al. 2009, Lim et al. 2000, Zhou 2007, Zhou et al. 2008a). With the polyploidy advantages and the variation caused by intergenomic recombination of 2n-gametes, many new cultivars have been directly selected from such allotriploid BC1 progenies by lily breeders (Zhang et al. 2012, Zhou et al. 2008a). OTO, which has two sets of O-chromosomes and one set of T-chromosomes, is one of the most promising allotriploid lilies because of the large flowers, strong stems and fragrance.

It is well known that most Polygonum-type triploid plants, such as triploid watermelon and banana, are sterile and seedless, so are usually not the ideal source for further introgression breeding (Brandham 1982). In contrast, the triploid lilies (2n = 3x = 36), both autotriploid (AAA) and allotriploid (AOA, LAA, LLO), can be used as maternal parents to hybridize with appropriate diploid (2n = 2x = 24) or tetraploid lilies (2n = 4x = 48), although they are also male sterile due to abnormal meiosis (Barba-Gonzalez et al. 2006, Chung et al. 2013, Khan et al. 2009, Lim et al. 2003, Natenapit et al. 2010, Xie et al. 2010, Zhou 2007, Zhou et al. 2011, 2012). The basis for this is the difference in the embryo sac formation between Polygonum-type and Fritillaria-type plants. From normal megasporogenesis of the Fritillaria-type embryo sac, Zhou (2007) deduced that triploid lilies produce aneuploid eggs and hexaploid central cells (secondary nuclei). Based on the crossability of these 3x × 2x/4x interploid hybridizations, the “Five same genomes of endosperm are essential for its development in Lilium” (“five-same-genomes”) hypothesis was proposed, to explain the success or failure of 3x × 2x/4x crosses in Lilium (Zhou et al. 2012) (see detail in discussion). Based on this hypothesis, we expected that OTO × OO crosses could be used in lily introgression breeding. However, very few cases regarding OTO lilies as the maternal parent have been reported (Chung et al. 2013, Zhou et al. 2012). In order to confirm whether the new theory applies to OTO × OO crosses, which would offer a new source for lily introgression breeding, we carried out controlled hybridizations between OTO and other diploid lilies, and analyzed their progenies using genomic in situ hybridization (GISH). We conclude with a discussion of the significance of allotriploids in lily introgression breeding.

Materials and Methods

Plant materials

Three OT cultivars (2n = 3x = 36) (‘Belladonna’, ‘Candy Club’ and ‘Travatore’) and two Oriental cultivars (2n = 2x = 24) (‘Siberia’ and ‘Sorbonne’) were supplied by Hongyue Flower Company, Hangzhou, China. One species, L. regale Wilson (2n = 2x = 24), was donated by Drs. Jisen Shi and Mengli Xi, Nanjing Forestry University, Nangjing, China. Since ‘Belladonna’, ‘Candy Club’ and ‘Travatore’ are allotriploid, with two sets of O-chromosomes and one set of T-chromosomes (Zhang et al. 2012), they were coded as OTOb, OTOc and OTOt, respectively. Similarly, the diploid Oriental cultivars ‘Siberia’ and ‘Sorbonne’ are represented by OOsi and OOso, and L. regale, the main origin of Trumpet lilies, by TT r. The OTO cultivars were used as the maternal donor and other diploid lilies as the paternal donor in the controlled hybridizations, and the crosses numbered 100513, 100539, etc. (Table 1).

Table 1.

Results of OTO × OO and OTO × TT hybridizations in Lilium

| Code | Maternal ♀ | Paternal ♂ | Flowers No. | Pollinating method | Capsules No. | Embryo sac No. | Embryo No. | Seedlings No. | Seedlings per capsule |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 100513 | OTOb | OOso | 19 | Normal | 18 | 115 | 4 | 31 | 1.6 |

| 100539 | OTOc | OOso | 14 | Normal | 13 | 78 | 4 | 11 | 0.8 |

| 100534 | OTOt | OOso | 8 | Normal | 7 | 31 | 0 | 7 | 0.9 |

| 100558 | OTOc | OOsi | 10 | Normal | 9 | 69 | 12 | 33 | 3.3 |

| 100512 | OTOb | TTr | 6 | Normal | 6 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 0.0 |

| 100531 | OTOc | TTr | 5 | Normal | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.0 |

| 100519 | OTOt | TTr | 5 | Normal | 5 | 7 | 0 | 0 | 0.0 |

Pollination and embryo rescue

At the end of September 2010, the cultivars were grown under natural light in a plastic greenhouse in Zhejiang University. When the temperature inside the greenhouse dropped to 18°C during winter, the automatic heating system was turned on. The flowering period was from the end of December 2010 to the beginning of January 2011. Pollination and embryo rescue were according to Zhou et al. (2013). Anthers were removed prior to anthesis. After pollination, styles were wrapped with aluminum foil. The soft or yellow fruits were cut off for in vitro embryo rescue in a laminar air flow cabinet because the seeds did not develop as well as normal seeds. Each was sterilized using 80% ethanol (Sinopharm Chemical Reagent Co. Ltd., Shanghai, China) for 3–5 seconds. The seed coats were carefully removed, and the embryo sacs or embryos put on a medium (pH = 5.8) containing 2.2 g·L−1 MS (Duchefa Biochemie, Haarlem, The Netherlands), 60 g·L−1 sucrose and 4 g·L−1 gelrite (Duchefa Biochemie). They were then germinated in a dark chamber at 25°C for 40–60 d, transferred to a medium (pH = 5.8) containing 2.2 g·L−1 MS, 50 g·L−1 sucrose and 4 g·L−1 gelrite (Duchefa Biochemie) at 25°C, and kept at 2500 lux light intensity for 12 hours per day for about 10 weeks.

Chromosome preparation

The protocol was according to Zhou et al. (2013). When lily roots of in vitro plantlets were approximately 1 cm long, they were cut off and pretreated with 0.7 mM cycloheximide (Amresco, Solon, OH), at room temperature for 4 h, and then fixed in ethanol: acetic acid (Sinopharm Chemical Reagent Co.) (3 : 1) overnight. Root tips were then softened with a 1% (w/v) cellulase RS (Duchefa Biochemie) and 1% (w/v) pectinase Y23 (Duthefa Biochemie) mix at 37°C for 1 h. The meristem was mixed with a drop of 45% acetic acid on a glass slide, covered with a glass cover slip and squashed. Each slide was examined under a phase contrast microscope (BH-2; Olympus, Tokyo, Japan) for in situ hybridization.

Genomic in situ hybridization (GISH)

The method was according to Zhou et al. (2013) with minor modifications. Genomic DNA of Oriental ‘Sorbonne’ and L. regale was isolated using the CTAB method (Rogers and Bendich 1988), and labeled with biotin-16-dUTP as the probe, according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Biotin- Nick translation Mix 11745824910; Roche, Mannheim, Germany). The hybridization mix (40 μL) contained 50% deionized formamide, 10% dextran sulfate, 2× SSC (0.3 M NaCl plus 30 mM sodium citrate, pH 7.0), 0.25% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS), 25–50 ng probe DNA and 2 μg herring sperm DNA (D3159, Sigma-Aldrich). Signal was detected with Streptavidin-CY3 (Invitrogen, Camarillo, CA) and Biotinylated anti-Streptavidin (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA). After counterstaining with DAPI (Roche), the slides were observed under a fluorescence microscope (BH41; Olympus). Images were taken with an attached CCD (Micropublisher 3.3 RTV; QImaging, Surrey, Canada) driven by Image-Pro® (Media Cybernetics, Rockville, MD).

Results

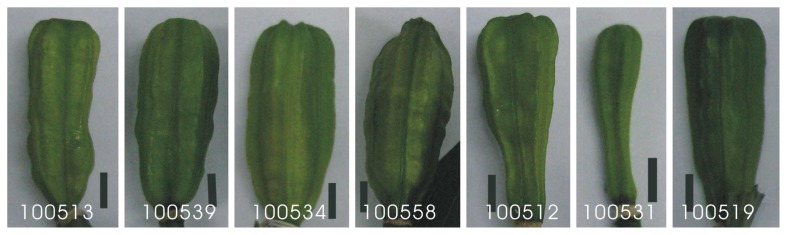

The main results of the 3x × 2x hybridizations are shown in Fig. 1 and Table 1. Capsules of OTO × OO combinations were usually more developed and larger than those of OTO × TT. All the OTO × OO combinations were successful. For example, for 100513 (Table 1), 19 flowers of OTOb were pollinated with OOso, 18 capsules were harvested for embryo rescue, and 119 well-developed seeds (including 115 embryo sacs and four embryos) were rescued. A final 31 seedlings were obtained. On average, 100513 produced 1.6 seedlings per ovary. Table 1 also shows that 100539, 100534, and 100558 produced 0.8, 0.9, and 3.3 seedlings per capsule respectively. In total, 82 seedlings were obtained from the OTO × OO combinations, while none from any OTO × TT combinations, indicating that OTO × OO hybridizations were more successful than OTO × TT combinations.

Fig. 1.

Representative fruits of OTO × OO and OTO × TT hybridizations, at harvesting stage for embryo rescue, indicate that the fruits of OTO × OO generally developed better than those of OTO × TT. 100513 = OTO‘Belladonna’ × OO‘Sorbonne’; 100539 = OTO‘Candy Club’ × OO‘Sorbonne’; 100534 = OTO‘Travatore’ × OO‘Sorbonne’; 100558 = OTO‘Candy Club’ × OO‘Siberia’; 100512 = OTO‘Belladonna’ × TT‘L. regale’; 100531 = OTO‘Candy Club’ × TT‘L. regale’; 100519 = OTO‘Travatore’ × TT‘L. regale’. Bar = 1 cm.

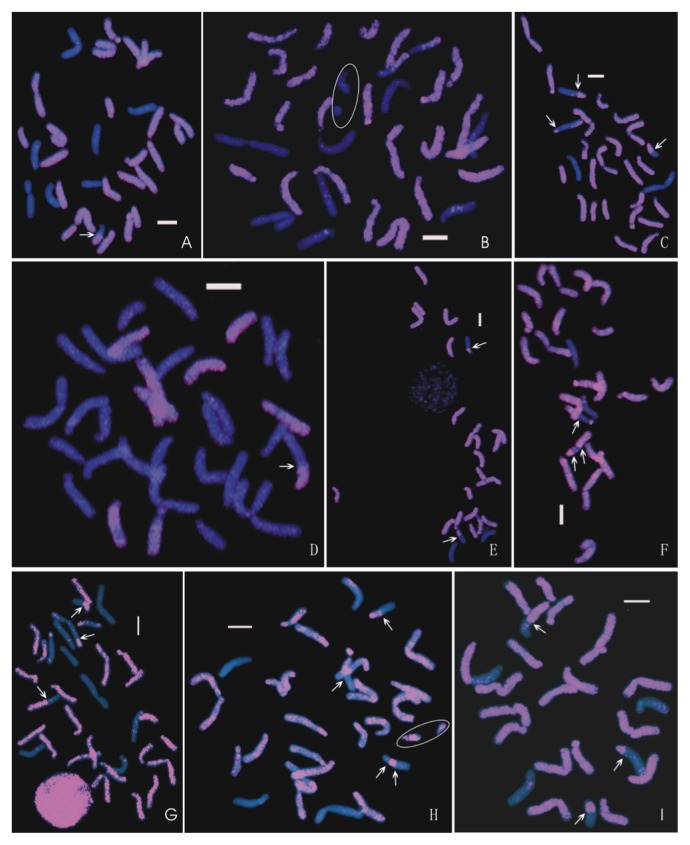

Nine seedlings were analyzed using GISH (Fig. 2). Seedling 100513-1 (Table 2) had 32 chromosomes in total: 24 O-chromosomes (Och), seven T-chromosomes (Tch), and one recombinant chromosome (O/Tch). Since 12 of these 32 chromosomes were contributed by pollen (Pollench), the other 20 chromosomes were contributed by egg (Eggch). It is evident that all of them were aneuploid with 25 to 33 chromosomes, indicating that they are the result of haploid sperm fusing with aneuploid eggs produced by the OTO maternal parents (Table 2). Except for 100539-4, the other eight seedlings contained between one and three recombinant chromosomes, suggesting that allotriploid OTO lilies are a good source for lily introgression breeding.

Fig. 2.

Genomic in situ hybridization (GISH) on the metaphase chromosomes of the nine progenies of OTO × OO hybridizations, demonstrating the chromosomal variation caused by the triploid OTO lilies. In D, T-genome DNA was labeled with biotin and used as probe so the T-chromosomes are pink and O-chromosomes are blue. In all other images, the O-genome DNA was labeled with biotin and used as probe, so the O-chromosomes are pink and the T-chromosomes blue. Arrows indicate the recombination point. The chromosomes marked with an ellipse in images B and H were damaged and part of them is lacking. Bar = 10 μm. (A) 100513-3 (2n = 24O + 7T + 1O/T); (B) 100539-4 (2n = 24O + 9T); (C) 100558-1 (2n = 22O + 2T + 3O/T); (D) 100558-5 (2n = 23O + 8T + 1O/T); (E) 100558-11 (2n = 21O + 2T + 2O/T); (F) 100558-13 (2n = 21O + 2T + 2O/T); (G) 100558-14 (2n = 21O + 9T + 3O/T); (H) 100558-20 (2n = 22O + 4T + 3O/T); (I) 100558-23 (2n = 21O + 3T + 3O/T).

Table 2.

The chromosome number of one seedling of 100513, one of 100539, and seven of 100558, illustrating variation in their total chromosomes (Chromosome no.), Oriental chromosomes (Och), Trumpet chromosomes (Tch) and recombinant chromosomes (O/Tch), and chromosome numbers contributed by pollen (Pollench) and egg (Eggch)

| Code | Chromosome no. | Och (no.) | Tch (no.) | O/Tch (no.) | Pollench (no.) | Eggch (no.) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 100513-3 | 32 | 24 | 7 | 1 | 12 | 20 |

| 100539-4 | 33 | 24 | 9 | 0 | 12 | 21 |

| 100558-1 | 27 | 22 | 2 | 3 | 12 | 15 |

| 100558-5 | 33 | 23 | 8 | 1 | 12 | 21 |

| 100558-11 | 25 | 21 | 2 | 2 | 12 | 13 |

| 100558-13 | 25 | 21 | 2 | 2 | 12 | 13 |

| 100558-14 | 33 | 21 | 9 | 3 | 12 | 21 |

| 100558-20 | 29 | 22 | 4 | 3 | 12 | 17 |

| 100558-23 | 27 | 21 | 3 | 3 | 12 | 15 |

Discussion

The present results show that, while OTO × OO hybridizations are successful, OTO × TT are not. This is expected from the “five-same-genomes” hypothesis and so strongly supports the hypothesis. As for the variation of different OTO × OO combinations, it is reasonable that genetic differences between cultivars are the main factor causing it.

The present results coincide to a large extent with those reported for other types of triploid lilies, which usually demonstrate limited female fertility and produce aneuploid progenies (Barba-Gonzalez et al. 2006, Chung et al. 2013, Khan et al. 2009, Lim et al. 2003, Xie et al. 2010, Zhou et al. 2011, 2012). They differ from Polygonum-type triploid plants which are sterile and seedless, or produce a small number of euploid progenies through 3x × 2x/4x interploid hybridizations (Brandham 1982, Carputo and Barone 2005, Ramsey and Schemske 1998, 2002). The reason for the difference has been well explained by analyzing the difference between Fritillaria-type embryo sacs of Lilium and the Polygonum-type embryo sacs of most other plants (Zhou et al. 2011). From diploid normal megasporogenesis, it has been deduced that megasporogenesis in triploid Polygonum-type plants results in embryo sacs that contain aneuploid eggs and aneuploid central cells, while embryo sacs in Fritillaria-type triploid plants contain aneuploid eggs and euploid (6x) central cells (Zhou 2007). After double fertilization in 3x × 2x/4x crosses, survival of Lilium aneuploid embryos is due to the euploid endosperm, while only a small number of euploid progenies are obtained in triploid Polygonum-type plants (Zhou et al. 2011).

The key factor in determining success or failure of hybridization is the compatibility of the parents. In the present research, OTO × OO crosses were often successful while all OTO × TT combinations failed, indicating that OTO and OO are compatible. The result can be well explained by the recent “five-same-genomes” hypothesis (Zhou et al. 2012). Because the amount of nuclear DNA in Lilium central cells is invariably twice that of somatic cells (Zhou 2007), the endosperm genome composition of any lily hybridization can be identified (Table 3). For example, an allotriploid lily (OTO) produces central cells containing four Oriental (O) genomes and two Trumpet (T) genomes, i.e., 4O + 2T, while a diploid OO lily generates pollen grains containing one Oriental genome, so the endosperm genome composition of OTO × OO hybridizations is 5O + 2T. From Table 3, it can be concluded that the endosperm of hybridizations develop well, and the hybridizations are relatively successful, when they contain 5 or more same genomes (+); otherwise, the hybridizations are not likely to be successful (−) (Zhou et al. 2012). In the present research, the endosperm of OTO × OO progeny contains 5 O-genomes and 2 T-genomes, hence the endosperm develops well and hybridizations are more successful. In contrast, the endosperm of OTO × TT crosses contains 4 O-genomes and 3 T-genomes, and hybridizations fail. These results give major support to the recent hypothesis.

Table 3.

Relationship between the endosperm genome composition and crossability in lily hybridizations

| Hybridizaitons | Central cell | Sperm | Endosperm | Crossability | References | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| Maternal (♀) | Paternal (♂) | |||||

| AA | AA | 4A | A | 5A | +++ | McRae 1998 |

| OTO | OO | 4O + 2T | O | 5O + 2T | + | This research |

| LAA | AA | 4A + 2L | A | 5A + 2L | + | Lim et al. 2003 |

| LAA | AAAA | 4A + 2L | 2A | 6A + 2L | ++ | Zhou et al. 2012 |

| LAA | LALA | 4A + 2L | L + A | 5A + 3L | + | Lim et al. 2003 |

| AOA | AA | 4A + 2O | A | 5A + 2O | + | Barba-Gonzalez et al. 2006 |

| AOA | OAOA | 4A + 2O | O + A | 5A + 3O | + | Barba-Gonzalez et al. 2006 |

| LLO | LLTT | 4L + 2O | L + T | 5L + 2O + T | + | Xie et al. 2010 |

| AAA | AA | 6A | A | 7A | + | Zhou et al. 2011 |

| AAA | AAAA | 6A | 2A | 8A | ++ | Zhou et al. 2011 |

| OTO | TT | 4O + 2T | T | 4O + 3T | − | This research |

| LAA | LL | 4A + 2L | L | 4A + 3L | − | Zhou et al. 2012 |

| LAA | OO | 4A + 2L | O | 4A + 2L + O | − | Zhou et al. 2012 |

The successful (+) hybridizations produce endosperms with 5 or more same genomes while the unsuccessful (−) hybridizations produce endosperm with less than 5 same genomes. The more plus (+) symbols, the more successful the hybridization.

Other mechanisms for explaining success or failure of plant hybridizations have been described. A 2 : 1 ratio of maternal : paternal genomes of the endosperm itself was proposed by Nishiyama and Inomata (1966). Unfortunately, it cannot explain the success of 2x × 4x and 4x × 2x hybridizations in many plants. EBN (endosperm balance number) has been proposed as a basis for explaining hybridizations between Solanum species (Johnston et al. 1980, Johnston and Hanneman 1982) and other species (Carputo et al. 1999, Carputo and Barone 2005). The difficulty of the EBN hypothesis is that the value of any parent EBN has to be assigned by hybridizations with a standard species. These hypotheses do not conflict with that of the ‘five-same-genomes’ because the 2 : 1 ratio and the EBN are applied to Polygonum-type plants while ‘five-same-genomes’ is applicable to Fritillaria-type plants. All the mechanisms demonstrate that endosperm genomic constitution is essential for success or failure of hybridizations in angiosperms.

Modern lily intra-sectional cultivars are usually diploid and most inter-sectional cultivars are triploid (Li et al. 2011, Zhang et al. 2012). Few commercial cultivars are aneuploid (Zhou et al. 2008a), although triploid lilies can be used as the maternal line to hybridize with appropriate males to produce aneuploid progenies. The reason for this is unclear, but it is known that aneuploidy is quite common in Hyacinth cultivars (Rees 1972). Aneuploidy causes considerable variation in morphological and biological traits, thus increasing the diversity for cultivar development. Lily is also easily propagated by micropropagation and bulb scaling, making it possible to multiply promising aneuploid lines. We do not consider that allotriploidy is a bottleneck in lily introgression breeding, and believe that aneuploids will become an important part of new lily cultivar development in the near future.

Acknowledgements

We thank the National Natural Science Foundation of China (31071821) and project 863 (2011AA100208) for financial support, Dr. Shirley Burgess for English correction and Drs. Jisen Shi and Mengli Xi for supplying L. regale.

Literature Cited

- Barba-Gonzalez, R., Lokker, A.C., Lim, K.B., Ramanna, M.S. and Van Tuyl, J.M. (2004) Use of 2n gametes for the production of sexual polyploids from sterile Oriental × Asiatic hybrids of lilies (Lilium). Theor. Appl. Genet. 109: 1125–1132 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barba-Gonzalez, R., Lim, K.B., Ramanna, M.S. and Van Tuyl, J.M. (2005a) Occurrence of 2n gametes in the F1 hybrids of Oriental × Asiatic lilies (Lilium): Relevance to intergenomic recombination and backcrossing. Euphytica 143: 67–73 [Google Scholar]

- Barba-Gonzalez, R., Ramanna, M.S., Visser, R.G.F. and Van Tuyl, J.M. (2005b) Intergenomic recombination in F1 lily hybrids (Lilium) and its significance for genetic variation in the BC1 progenies as revealed by GISH and FISH. Genome 48: 884–894 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barba-Gonzalez, R., Van Silfhout, R.A.A., Visser, R.G.F., Ramanna, M.S. and Van Tuyl, J.M. (2006) Progenies of allotriploids of Oriental × Asiatic lilies (Lilium) examined by GISH analysis. Euphytica 151: 243–250 [Google Scholar]

- Brandham, P.E. (1982) Inter-embryo competition in the progeny of autotriploid Aloineae (Liliaceae). Genetica 59: 29–42 [Google Scholar]

- Carputo, D., Monti, L., Werner, J.E. and Frusciante, L. (1999) Uses and usefulness of endosperm balance number. Theor. Appl. Genet. 98: 478–484 [Google Scholar]

- Carputo, D. and Barone, A. (2005) Ploidy level manipulations in potato through sexual hybridization. Ann. Appl. Biol. 146: 71–79 [Google Scholar]

- Chung, M.Y., Chung, J.D., Ramanna, M.S., Van Tuyl, J.M. and Lim, K.B. (2013) Production of polyploids and unreduced gametes in Lilium auratum × L. henryi hybrid. Intl. J. Biol. Sci. 9: 693–701 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnston, S.A., Den Nijs, T.M., Peloquin, S.J. and Hanneman, R.E.Jr. (1980) The significance of genic balance to endosperm development in interspecific crosses. Theor. Appl. Genet. 57: 5–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnston, S.A. and Hanneman, R.E.Jr. (1982) Manipulations of Endosperm Balance Number overcome crossing barriers between diploid species. Science 217: 446–448 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khan, N., Zhou, S., Ramanna, M.S., Arens, P., Herrera, J., Visser, R.G.F. and Van Tuyl, J.M. (2009) Potential for analytic breeding in allopolyploids: an illustration from Longiforum × Asiatic hybrid lilies (Lilium). Euphytica 166: 399–409 [Google Scholar]

- Li, K., Zhou, G., Ren, G., Zhang, X., Guo, F. and Zhou, S. (2011) Observation on ploidy levels of lily cultivars. Acta Hort. Sinica 38: 970–976 [Google Scholar]

- Lim, K.B., Chung, J.D., Van Kronenburg, B.C.E., Ramanna, M.S., De Jong, J.H. and Van Tuyl, J.M. (2000) Introgression of Lilium rubellum Baker chromosomes into L. Longiflorum Thunb.: a genome painting study of the F1 hybrid, BC1 and BC2 progenies. Chromosome Res. 8: 119–125 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim, K.B., Ramanna, M.S., Jacobsen, E. and Van Tuyl, J.M. (2003) Evaluation of BC2 progenies derived from 3x × 2x and 3x × 4x crosses of Lilium hybrids: A GISH analysis. Theor. Appl. Genet. 106: 568–574 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McRae, E.A. (1998) Lilies: A guide for growers and collectors. Timber Press, Portland, OR, USA [Google Scholar]

- Natenapit, J., Taketa, S., Narumi, T. and Fukai, S. (2010) Crossing of the allotriploid LLO hybrid and Asiatic lilies (Lilium). Hort. Environ. Biotechnol. 51: 426–430 [Google Scholar]

- Nishiyama, I. and Inomata, N. (1966) Embryological studies on cross-incompatibility between 2x and 4x in Brassica. Jpn. J. Genet. 41: 27–42 [Google Scholar]

- Ramsey, J. and Schemske, D.W. (1998) Pathways, mechanisms, and rates of polyploidy formation in flowering plants. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Systematics 29: 467–501 [Google Scholar]

- Ramsey, J. and Schemske, D.W. (2002) Neopolyploidy in flowering plants. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Systematics 33: 589–639 [Google Scholar]

- Rees, A.R. (1972) The Growth of Bulbs. Academic Press, London, UK [Google Scholar]

- Rogers, S.O. and Bendich, A.J. (1988) Extraction of DNA from plant tissues. In: Gelvin, S.B. and Schilperoort, R.A. (eds.) Plant Molecular Biology Manual, Kluwer Academic Publishers, Dordrecht, The Netherland, pp. 1–11 [Google Scholar]

- Van Tuyl, J.M., Keijzer, C.J., Wilms, H.J. and Kwakkenbos, A.A.M. (1988) Interspecific hybridization between Lilium longiflorum and the white Asiatic hybrid ‘Mont Blanc’. Lily Yearbook North Am. Lily Soc. 41: 103–111 [Google Scholar]

- Van Tuyl, J.M., Van Diën, M.P., Van Creij, M.G.M., Van Kleinwee, T.C.M., Franken, J. and Bino, R.J. (1991) Application of in vitro pollination, ovary culture, ovule culture and embryo rescue for overcoming incongruity barriers in interspecific Lilium crosses. Plant Sci. 74: 115–126 [Google Scholar]

- Van Tuyl, J.M., Van Dijken, A., Chi, H.S., Lim, K.B., Villemoes, S. and Van Kronenburg, B.C.E. (2000) Breakthroughs in interspecific hybridization of lily. Acta Hort. 508: 83–90 [Google Scholar]

- Van Tuyl, J.M., Maas, I.W.G.M. and Lim, K.B. (2002a) Introgression in interspecific hybrids of lily. Acta Hort. 570: 213–218 [Google Scholar]

- Van Tuyl, J.M., Lim, K.B. and Ramanna, M.S. (2002b) Interspecific hybridization and introgression. In: Vainstein, A. (ed.) Breeding for ornamentals: Classical and Molecular Approaches, Kluwer Academic Publishers, Dordrecht, The Netherland, pp. 85–103 [Google Scholar]

- Xie, S., Ramanna, M.S. and Van Tuyl, J.M. (2010) Simultaneous identification of three different genomes in Lilium hybrids through multicolour GISH. Acta Hort. 855: 299–303 [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, X., Ren, G., Li, K., Zhou, G. and Zhou, S. (2012) Genomic variation of new cultivars selected from distant hybridization in Lilium. Plant Breed. 131: 227–230 [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, S. (2007) Intergenomic recombination and introgression breeding in Longiflorum × Asiatic lilies (Lilium). PhD Diss., Wageningen Univ., Wageningen, The Netherlands [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, S., Ramanna, M.S., Visser, R.G.F. and Van Tuyl, J.M. (2008a) Genome composition of triploid lily cultivars derived from sexual polyploidization of Longiflorum × Asiatic hybrids (Lilium). Euphytica 160: 207–215 [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, S., Ramanna, M.S., Visser, R.G.F. and Van Tuyl, J.M. (2008b) Analysis of the meiosis in the F1 hybrids of Longiflorum × Asiatic (LA) of lilies (Lilium) using genomic in situ hybridization. J. Genet. Genomics 35: 687–695 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, S., Zhou, G. and Li, K. (2011) Euploid endosperm of triploid × diploid/tetraploid crosses results in aneuploid embryo survival in Lilium. HortScience 46: 558–562 [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, S., Li, K. and Zhou, G. (2012) Analysis of endosperm development of allotriploid × diploid/tetraploid crosses in Lilium. Euphytica 184: 401–412 [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, S., Tan, X., Fang, L., Jian, J., Xu, P. and Yuan, G. (2013) Study of the female fertility of an odd-tetraploid of Lilium and its potential breeding significance. J. Am. Soc. Hort. Sci. 138: 114–119 [Google Scholar]