Abstract

Background

Vancouver’s Downtown Eastside is home to Canada’s largest street-based drug scene and only supervised injection facility (Insite). High levels of violence among men and women have been documented in this neighbourhood. This study was undertaken to explore the role of violence in shaping the socio-spatial relations of women and ‘marginal men’ (i.e., those occupying subordinate positions within the drug scene) in the Downtown Eastside, including access to Insite.

Methods

Semi-structured qualitative interviews were conducted with 23 people who inject drugs (PWID) recruited through the Vancouver Area Network of Drug Users, a local drug user organization. Interviews included a mapping exercise. Interview transcripts and maps were analyzed thematically, with an emphasis on how gendered violence shaped participants’ spatial practices.

Results

Hegemonic forms of masculinity operating within the Downtown Eastside framed the everyday violence experienced by women and marginal men. This violence shaped the spatial practices of women and marginal men, in that they avoided drug scene milieus where they had experienced violence or that they perceived to be dangerous. Some men linked their spatial restrictions to the perceived 'dope quality' of neighbourhood drug dealers to maintain claims to dominant masculinities while enacting spatial strategies to promote safety. Environmental supports provided by health and social care agencies were critical in enabling women and marginal men to negotiate place and survival within the context of drug scene violence. Access to Insite did not motivate participants to enter into “dangerous” drug scene milieus but they did venture into these areas if necessary to obtain drugs or generate income.

Conclusion

Gendered violence is critical in restricting the geographies of men and marginal men within the street-based drug scene. There is a need to scale up existing environmental interventions, including supervised injection services, to minimize violence and potential drug-related risks among these highly-vulnerable PWID.

Keywords: Injection drug use, gender, violence, masculinity, supervised injection facilities, qualitative, social geography

INTRODUCTION

Street-based drug scenes are key risk environments for injection drug-using populations (Rhodes, 2009). These are typically defined as geographically-bound areas within urban centers characterized by high concentrations of people who use drugs and street-based drug dealing (Hough & Natarajan, 2000). Street-based drug scenes encompass multiple overlapping drug scene milieus that include but are not limited to public injection settings (Rhodes et al., 2007; Small et al., 2007), shooting galleries (Ouellet et al., 1991), homeless encampments (Bourgois & Schonberg, 2009), and sex work strolls (Shannon et al., 2008a). Exposure to these settings has been identified as a risk factor for violence (El-Bassel et al., 2005; Klein & Levy, 2003). Accordingly, people who inject drugs (PWID) are significantly more likely to experience violence than the general population (Chermack & Blow, 2002; Finlinson et al., 2003), with one recent epidemiological study finding that 70% and 66% of male and female PWID, respectively, experienced violence over a five-year period (Marshall et al., 2008).

A considerable body of evidence highlights how violence within street-based drug scenes operates at the ‘structural’ (Farmer, 2005), ‘everyday’ (Scheper-Hughes, 1992), and ‘symbolic’ levels (Bourdieu & Wacquant, 1992). Structural violence is produced by social arrangements within society determined by large-scale forces (e.g., racism, sexism) that inflict injury upon vulnerable populations (Farmer, 2005). Everyday violence refers to the normalization of violence that is rendered invisible due to its pervasiveness (Scheper-Hughes, 1992), and is often embedded within gendered power relations (Bourgois, Prince & Moss, 2004). Finally, symbolic violence is the product of social forces that lead vulnerable groups to misrecognize their subordination as the natural order of things and often blame themselves for the suffering experienced due to their social position (Bourdieu & Wacquant, 1992).

Epidemiological data underscore how intersecting structural inequities that impact upon street-based drug scenes, including homelessness (Duff et al., 2011; Shannon et al., 2009) and drug and sex work law enforcement (Kerr et al. 2005; Shannon et al., 2008a), increase exposure to violence. Ethnographic and qualitative studies further underscore how social norms operating within drug scenes perpetuate everyday violence (Bourgois et al., 2004; Epele, 2002; Shannon et al., 2008b). Previous research has described how the subordination of women within street-based drug scenes is expressed through violence, particularly that directed from ‘boyfriends’ (i.e., men who control the resources women generate through exchanging sex) and sex work clients (Bourgois et al., 2004; Bungay et al., 2010). Furthermore, the tendency among PWID to identify women’s subordination as natural underscores the symbolic dimensions of drug scene violence (Bourgois et al., 2004).

Violence among PWID is an urgent public health concern given its direct impacts and association with drug-related harm. Previous studies have primarily concentrated on drug-using women (Braitstein et al., 2003; El-Bassel et al., 2005; Vlahov et al., 1998), linking violence to elevated rates of syringe-sharing (Braitstein et al., 2003), inconsistent condom use (El-Bassel et al., 2005), and accidental overdose (Braitstein et al., 2003). Furthermore, violence or the threat of violence in settings where drug-using women exchange sex have been found to undermine their ability to negotiate safer sex work transactions (Shannon et al., 2008b).

Although male PWID are also likely to experience drug scene violence, comparatively less attention has been paid to the associated risks and consequences outside of studies linking experiences of violence among male PWID with an increased likelihood of depression (Curry et al., 2008), and death due to homicide (Clausen et al., 2009). The limited attention to violence among drug-using men reflects an emphasis on gender-based violence in the drug use literature, which is viewed primarily as violence perpetrated against women by men (Marshall et al., 2008). Epidemiological studies of drug scene violence have tended to concentrate on biological sex or define gender as a binary, and have emphasized women’s vulnerability to inter-partner violence or violence in the context of sex work (El-Bassel et al., 2005; Shannon et al., 2009). Whereas several ethnographic and qualitative studies have linked violence against women within drug scenes to gendered power relations, and examined how it is produced by gender norms that subordinate women (Bourgois et al., 2004; Bungay et al., 2010; Shannon et al., 2008b), they have not considered the role of a wider range of ‘gender positions’ in shaping violence.

An alternative view may consider how gendered violence is produced by hegemonic forms of masculinity that operate within street-based drug scenes, which render women and ‘marginal men’ vulnerable to violence due to their marginal positions within gendered hierarchies. Hegemonic masculinity may be understood to be a set of practices occurring within any particular context, in this case the street-based drug scene, through which some men subordinate or control women and ‘marginal’ masculinities (Connell & Messerschmidt, 2005). Violence toward those occupying marginal positions within gendered hierarchies is one of the ‘practices’ through which hegemonic masculinity is expressed and reinforced (Stoudt, 2006).

Although limited, evidence suggests that the structure of street-based drug economies reflects and reinforces gendered hierarchies, in that men occupying more prominent roles (e.g., drug dealers) subordinate women and marginal men. While some women occupy roles within drug economies that allow them greater claims to agency (Maher, 1997; Shannon et al., 2008b), women are nonetheless largely confined to marginal positions (Maher & Hudson, 2007). Moreover, the marginal positions of some men are often determined by the lower status accorded to their income-generating strategies within the street-based economies (e.g., panhandling, recycling) (Bourgois & Schonberg, 2009). Following Connell and Messerschmidt (2005), we extend this view of marginal men within the context of street-based drug scenes to include men who do not—or cannot—occupy dominant roles due to age, disability, health status, social isolation (e.g., limited social ties within the drug scene), and specific drug use practices (e.g., requiring help injecting). While recognizing that women and marginal men’s experiences of violence are complex and unique, evidence from other settings suggest that dominant forms of masculinity increase vulnerabilities to violence and adverse health outcomes among women (Jewkes & Morrell, 2012) and marginal men (Canetto & Cleary, 2012; Courtenay, 2000), but this has been underexplored as a driver of violence within the context of drug scenes.

The Downtown Eastside (DTES) neighbourhood in Vancouver, British Columbia is the site of Canada’s largest street-based drug scene (Strathdee et al., 1997; Wood & Kerr, 2006), with an estimated 5,000 PWID living in this approximately ten-block area (Wood & Kerr, 2006). This neighbourhood has been shaped by the interplay between entrenched poverty, homelessness, and drug use (Wood & Kerr, 2006). Whereas numerous environmental supports are available to PWID in this neighbourhood, including North America’s only sanctioned supervised injection facility (Insite) and safer sex work environments (Krusi et al., 2012), research has documented the significant impact that violence has on neighbourhood PWID (Lazarus et al., 2011; Marshall et al., 2008; Shannon et al., 2008b). Notably, in a social mapping study among drug-using women who exchange sex, Shannon and colleagues (2008a) found that women commonly avoided main streets and core areas of the DTES with high concentrations of health services due to violence and police harassment.

However, there remains a need to explore how injection drug-using women and marginal men’s understandings and experiences of place and gendered violence shape their spatial practices—that is, how they actively negotiate space in the context of their everyday lives (de Certeau, 1984). Furthermore, studies into how gendered hierarchies frame the violence experienced by women and men who inject drugs, and the consequences of this violence, are needed. We undertook this study to explore the spatial practices of women and marginal men who inject drugs in the DTES, and how these are shaped by gendered violence. We were particularly concerned with how their spatial practices impacted their access to health and harm reduction services, including Insite.

METHODS

This study is based upon qualitative interviews and mapping exercises conducted with PWID in the DTES between September and December 2011. This research was undertaken in partnership with the Vancouver Area Network of Drug Users (VANDU), with whom members of our research team have collaborated for more than a decade. Two research team members (McNeil & Small) conducted semi-structured interviews with twenty-three PWID who regularly accessed VANDU. We aimed to oversample women relative to their representation within the local drug scene to facilitate the study of gendered patterns of risk and harm. We also prioritized the recruitment of participants whose specific injecting practices (e.g., requiring help injecting), income-generating strategies (e.g., sex work), health status or disability, or social isolation potentially increased vulnerability to harm, including violence. Seven participants were recruited by referral from VANDU staff, while the remaining participants were recruited within the context of a larger ethnographic project based at VANDU. The majority of interviews (n=20) were conducted at a storefront research office in the DTES, and the remaining interviews (n=3) were conducted in an office at VANDU. Participants provided written informed consent prior to their interviews and received an honorarium ($20 CAD) following its completion. Interviews were audio recorded and averaged approximately 45 minutes in length. Interviews were transcribed verbatim and reviewed for accuracy by the lead author. Ethical approval for this study was obtained from the Providence Healthcare / University of British Columbia institutional research ethics board.

We used an interview topic guide to facilitate discussion regarding how participants experienced place in the DTES, and how these experiences shaped their access to Insite. Given that local epidemiological data indicated that men and women who inject drugs experience high levels of violence, we were particularly concerned with how the social geographies of our participants were shaped by violence and perceptions of safety, and included questions focusing on gendered and spatial dimensions of violence. Interviews were accompanied by a qualitative mapping exercise that sought to link diverse experiences (including violence) to specific locations in the neighbourhood. During the interview, participants and interviewers made notes on neighbourhood maps to link diverse experiences and activities to specific locations. Participants were also asked to highlight areas that they perceived as safe or unsafe, including any areas in the neighbourhood that they avoided.

Interview transcripts and maps were imported into NVivo (v. 9) to facilitate data management and coding. We used a multi-step process to analyze our data. We first analyzed maps to identify patterns in the socio-spatial practices of our participants. We reviewed each map individually while keeping detailed analytic notes, and then compared and contrasted these notes to identify spatial patterns. We noted that women and men had similar spatial patterns (e.g., avoided particular areas). We then developed a coding framework based on these socio-spatial patterns and a priori categories extracted from the interview guide (e.g., understandings and experiences of violence, perceptions of the neighbourhood, reasons for avoiding particular areas), and used this to code the interview transcripts. We then linked interview data to the mapping data to develop thematic descriptions of these socio-spatial patterns. We noted that participants’ socio-spatial patterns were distinctly gendered, in that, while violence produced similar spatial patterns among women and marginal men, these were understood and positioned differently. We adjusted our coding framework to account for these similarities and differences, and then recoded the data to establish the final categories. Finally, we drew upon concepts of everyday, structural, and symbolic violence, and hegemonic masculinity, to situate the spatial practices of our participants within their gendered social and structural contexts. We then presented our final themes (i.e., contextualizing gendered violence and masculinity in the DTES; gendered violence and geographical restrictions; locating survival in the street-based drug scene; and, crossing boundaries) to the VANDU Board of Directors to solicit their feedback and ensure the reliability of our themes.

RESULTS

Sample Characteristics

The twenty-three individuals participating in semi-structured interviews included eleven women and twelve men. All of the men interviewed were identified as ‘marginal men’ insofar as they reported characteristics that diminished their status within the drug scene, including but not limited to: physical disabilities (n=4); requiring help injecting (n=4); sleeping outside (n=3); and, social isolation (n=5). Participants averaged approximately 40 years of age (range 27–59 years), and eight self-identified as a member of a visible minority (Aboriginal ancestry, African-Canadian, or Indo-Canadian). Most participants (n=20) indicated that they used drugs daily, with crack cocaine (n=20), heroin (n=12), hydromorphone (n=8), and cocaine (n=6) identified as the most commonly used drugs. All participants had lived in the DTES within the past five years, and nineteen currently lived there. Nearly half of our participants were staying in emergency shelters (n=8) or sleeping outside (n=3), while the remaining participants reported that they lived in single room occupancy hotels (n=6) or apartments (n=6). Nearly all participants received income primarily from social assistance payments (n=22), and most of the women (n=8) reported regularly exchanging sex.

Place, violence, and masculinity in the Downtown Eastside

Central to participant narratives of place in the DTES were gendered experiences of drug scene violence. Nearly all women and marginal men specified locations where they had been “threatened” or “attacked”, while those remaining spoke of locations where they had witnessed violence. Our findings demonstrate how the street-based drug scene was structured by a hegemonic form of masculinity predicated on violence and the subordination of women and marginal men. Women and marginal men were deemed to occupy lesser positions than ‘dominant men’ (i.e., drug dealers, “boyfriends”, violent drug users, and other men occupying central positions of power within the street-based drug economy) within the gendered power hierarchy in the street-based drug scene. Participants indicated that women and marginal men had limited ability to protect themselves from violence and exploitation, and indicated that this increased their vulnerability to violence and marked them as the targets of predatory dominant men when entering drug scene milieus. One woman in her late fifties remarked:

One guy’s in a wheelchair and he’s paralyzed on one side. He’s been a heroin addict for thirty years and he had a stroke…Every time he used to go to the alley, he’d get ripped off, beaten up, lose everything. [Female, 59 years old]

Women commonly spoke of the additional risks of violent sexual assault. For example, one woman in her late twenties who engaged daily in outdoor sex work noted:

I’ll smoke [crack cocaine] in the alley and I hate it…It’s scary. Anybody could walk up behind you with something and beat you and try to rob you ‘cause they want your drugs. It’s just scary…I’ve been raped [in an alleyway].

Gendered violence was understood to be a natural consequence of drug scene involvement, and thus operated as a form of symbolic violence. Many participants expressed that this normalized, gendered violence was most evident in the expectation that dominant men would seek to control the money and drugs or labour (e.g., contexts in which they exchanged sex) of women and marginal men. For example, as one older man noted during his interview:

The girls make the money [through involvement in sex work]. Guys know they got the money. The guys don’t make money, and that way they have to beg, borrow or steal in between cheques…So, of course they [women] are going to be manipulated…These guys, you know, [are] muscling them or doing anything to get what they’ve got [i.e., drugs or money].

Gendered violence and geographical restrictions

Our findings demonstrated that how women and marginal men positioned their geographical restrictions varied. Whereas women and some marginal men explicitly linked their spatial restrictions to violence, other men sought to position their spatial practices in a manner that resisted marginalized identities.

“Just not safe outside” – Avoiding ‘dangerous’ areas

While the everyday violence experienced by women and marginal men fuelled their perception that the neighbourhood was unsafe, their lack of access to private space, together with the realities of drug dependency and poverty, promoted immersion within the street-based drug scene. This intersection of structural and everyday violence increased their risk of violence by increasing their exposure to drug scene milieus. Accordingly, participants spoke of how they enacted spatial strategies to maintain their safety within the context of everyday violence. Mapping data further demonstrated that most of the areas in the neighbourhood where women and marginal men experienced drug scene violence were concentrated in high traffic drug market locations (e.g., areas along Hastings Street and west of Main Street, Oppenheimer Park) and secluded areas (e.g., alleyways). These participants indicated that they actively avoided these “dangerous” areas to limit their exposure to aggressive and violent men. While specific geographical restrictions varied among these participants in accordance with their individual experiences and perceptions of violence, their spatial strategies may be understood to be an adaptive response to the hegemonic form of masculinity operating within the street-based drug scene.

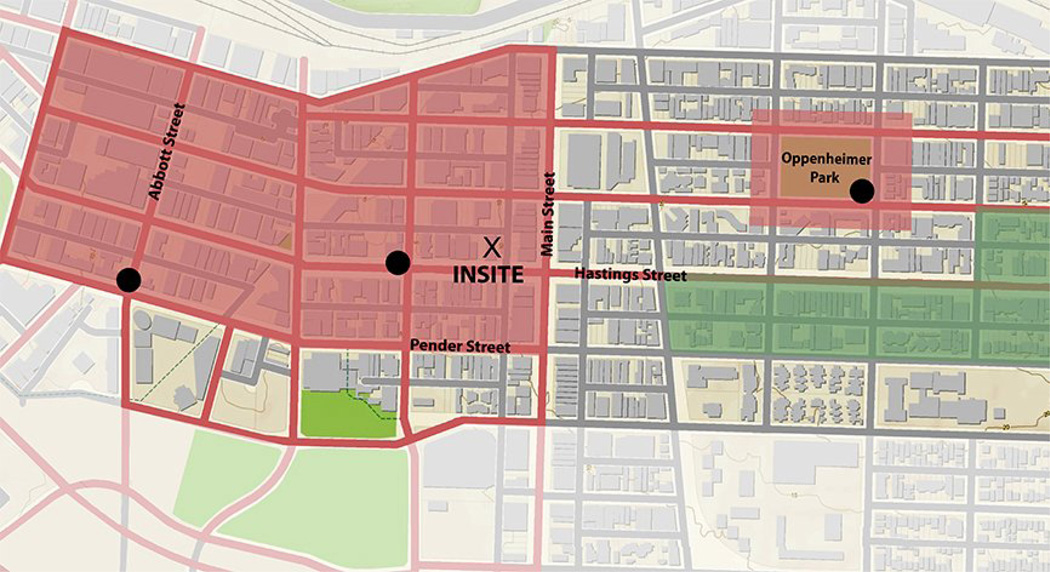

Importantly, this strategy had the effect of severely limiting the scope of the spatial practices of women and marginal men who had frequently experienced violence, as well as those who viewed themselves as especially vulnerable to violence due to their gender or disability. For example, “Ellen” was a woman in her early forties who had lived in the DTES for twenty years, having been originally drawn to the neighbourhood by the easy availability of heroin (n.b., pseudonyms are identified by pseudonyms randomly-generated through a web-based program). She had cycled between emergency shelters and single room occupancy hotels depending on her access to income (sex work), intensity of her substance use patterns, and on-again, off-again relationship with her “boyfriend”. Ellen had recently begun injecting crystal methamphetamine (in addition to heroin) and the subsequent intensification of her substance use patterns precipitated eviction from her single room occupancy hotel. Ellen discussed how her subsequent immersion in the street-based drug scene led to a violent assault by a male drug user and caused her to restrict the geographical scope of her activities to avoid specific areas and, generally, men.

I had no place to go, right, so I was either at the [emergency shelter] or [dropin centre]. Just walking around’s not safe. People approach you, men approach you. [It is] just not safe outside if you’re a girl… I had my armed chopped [by a man] with a machete. [Participant shows interviewer scarring] I kind of got scared…At that point in time, I was really nervous of guys. […] I try to avoid Oppenheimer [Park] and I try to avoid [the] Abbott and Pender [intersection]. I don’t like it there. That’s where my accident [i.e., machete attack] happened and Oppenheimer’s just scary.

The map generated by Ellen underscored the extent to which experiences of violence constrained her movements within the DTES (Figure 1). In addition to the abovementioned geographical restrictions, Ellen indicated that she generally avoided drug scene milieus west of Main Street where she had previously experienced violence. Similarly, our data demonstrated that intersecting inequities (e.g., poverty, homelessness) promoted participant immersion within the male-dominated drug scene, while at the same time producing gendered violence that led them to restrict the scope of their spatial practices. This had the effect of leading some women and marginal men to confine their movements to small areas that in some cases encompassed a few short blocks.

Figure 1.

Map of Ellen’s spatial practices

“I want the best dope” – Resisting marginalized masculinities

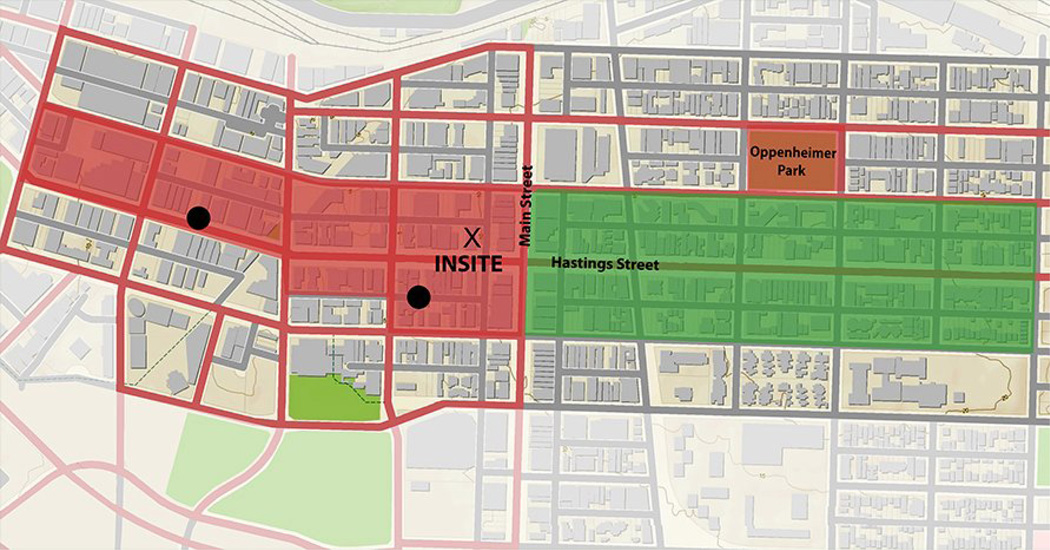

Despite their low status within the street-based drug scene and frequent experiences of violence, some men actively resisted marginalized masculinities by expressing that they would go anywhere in the neighbourhood. Nonetheless, mapping data revealed that these men tended to avoid high intensity drug market locations characterized by violence (e.g., alleyways, drug dealing locations). These men attributed their geographical restrictions to the perceived quality of drugs (particularly heroin) sold by dealers in these areas. These men had limited or precarious sources of income (e.g., social assistance, recycling), and articulated how the need to maximize their drug purchases, together with the desire for intense intoxication, led them to seek out highly potent drugs and reliable dealers. While the local street-based drug market is most established along Hastings Street and west of Main Street, these men characterized the drugs sold in this area as “shitty” (i.e., having inconsistent potency), and several reported that they had previously been “bunked” (i.e., sold counterfeit drugs) by dealers in that area. These men emphasized how the inferior quality of the drugs sold in these high intensity drug market locations left them with little reason to visit these areas.

Our analysis of participant accounts and maps suggests that these concerns about “dope quality” served to allow these men to maintain claims to dominant forms of masculinity while enacting spatial strategies (i.e., avoiding violent drug market locations) that limited their exposure to violence. Even as men attributed their geographical restrictions to poor dope quality, their narratives of these drug scene milieus emphasized drug scene violence at the hands of violent men, and many feared further violence. For example, “Alex” was a thirty-something homeless male PWID who had recently moved to Vancouver from Eastern Canada after hearing stories of the drug availability and quality in the DTES. He had been living in an emergency shelter for several months, and the intensity of his drug use patterns led him to quickly gain familiarity with the street-based drug scene. Alex indicated that drug dealers in several high intensity drug market locations sold “shitty dope”, and that he avoided those areas.

[Around the] bottle depot [located one block west of Insite], there is always a crowd of people [selling drugs]. There’s about five – I don’t know how many dealers. The dope is not that good. As a junkie, I want the best dope I can get for my money.

However, interview and mapping data suggest that Alex was primarily motivated by the need to avoid violence in these drug scene milieus. Notably, Alex had experienced violent assault at the hands of drug dealers and male drug users in areas that he avoided and perceived to be unsafe (Figure 2). For example:

Two guys came to me…They punch me in the face and I’m laying down, and there’s two pretty big guys and one says, “This is a fucking controlled block.” And pow! I get another one [punch] in the face. [It] pretty much knocked me out. They showed me their tattoos and I’m pretty sure they’re bikers because we don’t buy from the [high intensity drug market location]…They want us to buy their dope. …Now, I’m a little scared of people that might want to rob me, that want to, like, fucking punch me out. I’m a tough man. I can fight too but I lost a lot of weight.

Figure 2.

Map of Alex’s spatial practices

Locating survival within the street-based drug scene

Whereas gendered violence restricted the spaces occupied by women and marginal men, their accounts illustrated how they leveraged social resources to negotiate survival in the DTES. Several low-threshold housing programs (e.g., shelters, women-only housing), health care services (e.g., clinics, case management), and peerrun organizations (e.g., VANDU) operating east of Main Street figured prominently in participant accounts. Women and marginal men expressed that these were places where they could escape drug scene violence, with women emphasizing the importance of women-only spaces. The availability of these spaces was especially important among homeless or unstably housed women and marginal men who otherwise lacked access to spaces in which they could escape drug scene violence. For example, “James”, a homeless male PWID, spoke of how he spent as much time as possible at a drop-in program:

There’s like 40 crack dealers down by the bottle depot.I feel way safer [at the drop-in program] because [there is] none of that action [i.e., drug scene violence]…I was there [drop-in program] at 10 o’clock this morning and I’ve been in there since…I think they should be open 24 hours.

Many woman and marginal men contrasted the areas immediately surrounding these facilities with other drug scene milieus, and emphasized how the former were safer because of the additional environmental supports provided by these facilities, including regulated indoor environments.

Our analysis of participant accounts and maps further demonstrated that the availability of these environmental supports was critical in enabling women and marginal men to survive (e.g., obtaining food and shelter) or generate the income necessary to support continued drug use (e.g., sex work, stipended volunteer work). Many marginal men had limited involvement in the street-based economy, and their limited access to money meant that they were dependent upon these programs to obtain material resources, medical care, and social support that allowed them to survive within the context of entrenched poverty. Nearly all of the women that we interviewed engaged in sex work, and leveraged these organizations to increase their safety while working. Some women indicated that they worked primarily in close proximity to these organizations to limit their exposure to more dangerous drug scene milieus. Several women were also living in women-only housing programs that function as safer sex work environments (n.b., these programs have been described in detail elsewhere; see Krusi et al., 2012), and the availability of these supports was crucial in establishing a space for them.

Crossing boundaries – The need to enter drug scene milieus

Among women and marginal men, there was a stark contrast between dangerous drug scene milieus characterized by male perpetrated violence and safer areas located within their geographies of survival. These areas were separated by clearly defined boundaries that were only crossed under extreme duress, primarily when unable to obtain drugs from usual sources or as necessary for income-related reasons (e.g., cashing social assistance cheques). Participants described themselves as “stressed” when they were compelled to venture into these dangerous drug scene milieus, and emphasized how these border crossings increased their vulnerability to male perpetrated violence. For example, “David”, who was in is late forties, was in a motorized wheelchair due to a stroke, and had frequently been “ripped off” by men in the DTES. While David regularly exchanged prescribed oxycodone for hydromorphone with his longstanding dealer, he was sometimes unable to obtain his preferred drug in this way. The potential for opiate withdrawal led him to incur considerable risk by venturing into dangerous drug scene milieus where he had experienced violence.

Once I get down to that area [i.e., high traffic area in drug scene where prescription drugs are sold], I have to watch for people watching to see what I got…The only reason I’m there is if my regular connection [drug dealer] doesn’t have pills, and I’m forced to go down there to look for pills…Security is one of the reasons [for avoiding this area]…You just never know if they’re going to follow you and jump you.

Mary, a twenty-something Aboriginal woman who had been entrenched in the street-based drug scene since her early teens, was frequent the target of predatory men seeking control over the resources that she generated through sex work. Mary worked primarily in the area immediately surrounding her single room occupancy hotel, which functioned as a safer sex work environment (see Krusi et al., 2012), and spoke negatively of “ruthless” drug scene milieus west of Main Street. Nonetheless, there were income-related reasons why she had to occasionally cross this boundary.

Everybody’s so fucking ruthless and cold down there [i.e., west of Main Street]. […] They’ll fucking stab you if they wanted something you have…They try their hardest to fucking bring you down ‘cause they don’t want to see you doing better than them. […] If I go past Main [Street], it’s like, “Ho, where’s my fucking money?” or “give me that!” Down there it’s all negativity and violence and money and bullshit. I don’t want [that], don’t need [that]…I don’t go past Main [Street unless] it’s for something that, like, I have to have to. Then, I will. Like, on Mondays, I go to the cheque cashing place on Main… [That is] the only time I go on that side of Main. Other than that, I don’t even bother.

As these cases demonstrate, within the situated rationality of women and marginal men, there were instances when it was necessary to cross boundaries and enter potentially violent drug scene milieus. Notably, none of our participants cited accessing harm reduction services as a motivation for crossing these thresholds, despite the fact that the area immediately surrounding Insite was the most commonly avoided area. It was striking that most of our participants indicated that they rarely injected at Insite because they avoided the area and approximately one third had never injected at Insite, underscoring how gendered drug scene violence was critical in constraining access to these services. For example, “Alice”, a homeless woman in her late twenties engaged in sex work, had recently been attacked on the same block as Insite. Whereas she avoided the area surrounding Insite because it was perceived to be dangerous, her need to inject pushed her into other unsafe drug scene milieus.

I feel very, very unsafe down by the injection site [Insite]… I don’t go past Main [Street] anymore…There’s some very dangerous dealers down there…That’s where I was robbed and beaten badly…This guy robbed me and beat me up. I don’t go there at all [now]. […] If I have to use, I’ll use anywhere. I go into the alleys and I feel less safe [there].

DISCUSSION

In summary, we found that hegemonic forms of masculinity operating within the DTES perpetuated gendered violence toward women and marginal men, who restricted the geographic scope of their activities to avoid drug scene milieus where they had experienced violence. While some men attributed their geographical restrictions to the need to acquire high-quality drugs, their emphasis on drug scene violence suggested that this allowed them to maintain claims to dominant forms of masculinity while enacting spatial strategies necessary to their safety. Environmental supports provided by health and social care agencies were critical in enabling women and marginal men to negotiate survival within the context of gendered violence. Whereas access to harm reduction services, including Insite, was insufficient to motivate our women and marginal men to enter into “dangerous” drug scene milieus, they ventured into these areas when necessary to obtain drugs or for income-related reasons.

Our findings point to the central role of hegemonic masculinity in subordinating marginalized men, and thus shaping how they negotiate safety and survival within a street-based drug scene. Hegemonic masculinity operated at the symbolic level, in that marginal men seemingly accepted that their lower status within the drug scene rendered them vulnerable to violence. Marginal men’s narratives of place in this neighbourhood were interwoven with experiences of violence that profoundly impacted their spatial practices, which were linked to the need to maintain safety from the violence of dominant men within the street-based drug scene. Whereas the hegemonic form of masculinity within the street-based drug scene was tied to the street-based drug economy, men identified violence as its defining characteristic. While the concept of hegemonic masculinity has increasingly been employed to understand men’s health (Canetto & Cleary, 2012; Cleary, 2012) and risk-taking (Peralta, 2007), it has received only limited attention in drug use research, where it has focused primarily on the roles occupied within street drug economies (Bourgois, 2003; Hutton, 2005) and specific injection practices (Bourgois & Schonberg, 2009; Nasir & Rosenthal, 2009).

Our findings expand upon the literature by underscoring how the tendency within the drug use research to homogenize male populations overlooks the extent to which men’s experiences may be defined by their masculine subject positions. Our study demonstrates that greater attention to masculinities is warranted given their considerable potential to explain variations in the distribution of drug-related harm among men. Ethnographic and qualitative research that examines gendered power hierarchies within street-based drug scenes is likely to prove important in typologizing masculinities, and informing more nuanced epidemiological analyses. Together, these approaches have the potential to advance theoretical understandings of the gendered contexts of drug-related harm and inform targeted interventions to meet the better needs of vulnerable men.

Whereas previous research has emphasized the role of street policing in displacing women within drug scenes (Cooper et al., 2005; Shannon et al., 2008b), our findings expand upon emerging evidence linking drug scene violence to women’s displacement from drug scene milieus (Shannon et al., 2008a). Importantly, although drug and sex work laws produce structural violence within street-based drug scenes, the lack of discussion of street policing in women’s narratives likely reflects recent shifts away from the strict enforcement of these laws in the DTES (Deering et al., 2012; Small et al., 2012). Furthermore, these women lacked involvement in activities other than sex work (e.g., drug selling) that might have drawn the attention of police. Conversely, consistent with the broader literature linking gendered power relations and how women negotiate urban geographies (Mehta, 1999; Pain, 1997; Valentine, 1989), we found that the dominant form of masculinity that structured gendered power relations in DTES and normalized violence toward women. Specifically, our findings highlight how gendered violence dictated women’s spatial practices, and thus excluded them from drug scene milieus. While it is critical that future examinations of women’s geographies within street-based drug scenes locate these within the context of gendered violence, it is equally important that such research consider how environmental interventions can be mobilized to mitigate violence by providing increased supports and opportunities to achieve safety.

Women and marginal men were able to negotiate survival by leveraging social resources available in the neighbourhood. These organizations provided women and marginal men with spaces that they could occupy with limited risk of violence, and thus engage in a wide range of activities critical to their survival. Whereas recent evidence underscores the critical role of targeted environmental supports, including safer sex work environments (Krusi et al., 2012) and women-only housing (Lazarus et al., 2011), in mitigating the deleterious impacts of gendered violence within street-based drug scenes, our research underscores the importance of considering the overall coverage of environmental supports. Scaling up interventions (e.g., targeted housing and drop-in programs) is likely necessary to ensure optimum coverage and better promote safety among women and marginal men.

Our findings demonstrate how violence constrained access to supervised injection services among women and marginal men. Although previous research has found Insite to be a ‘refuge’ from violence for women (Fairbairn et al., 2008), we found that some women and men are unable to even access the facility due to the perceived threat of violence in the surrounding area. Whereas Insite may be able to take direct steps to minimize violence in its immediate vicinity by providing additional environmental supports, including anti-violence prevention programming in street-based settings, these are unlikely to be enough to ensure access to supervised injection services among those who nonetheless continue to view the area as unsafe. Our findings suggest that greater diversity of supervised injection facilities may be needed to ensure appropriate harm reduction coverage. Despite growing calls to expand these services in Vancouver, and increased awareness of the limitations of the current centralization of supervised injection services (Marshall et al., 2011; Petrar et al., 2007), there remains a need to scale up these services in the DTES and elsewhere in Vancouver with established drug scenes. Situating supervised injection services within the existing geographies of survival of women and marginal men (e.g., integrating services into shelters, supportive housing) or implementing mobile safer injecting services may improve their responsiveness to the social geographies of highly-vulnerable PWID.

Finally, our findings demonstrate the need for policy reforms to maximize the impact of targeted environmental interventions, and to create an environment in which highly-marginalized PWID can minimize their exposure to violence. The extent to which immersion in the street-based drug scene was driven by homelessness and housing instability underscores the need to increase investment in safe, affordable housing. Despite recent efforts in the local context to increase the availability of social housing, the demand far exceeds the supply, and a more comprehensive approach that involves all levels of government is needed. Furthermore, our findings lend support to continuing calls for legislative reforms to enable those engaged in sex work to negotiate safety (Krusi et al., 2012). Consistent with previous research (Krusi et al., 2012), our findings demonstrate that the availability of safer sex work environments was critical in improving women’s safety, and policy reforms to enable those engaged in sex work to access regulated and safe indoor environments are needed.

There are several limitations to this study. First, findings reflect the experiences of our participants, and cannot be considered to be representative of all drug users in the DTES. It is possible that those recruited in other locales in this neighbourhood would have different spatial practices. Second, because recruitment and data collection were undertaken in connection with VANDU, our insights may be limited to the perspectives of their members and reflect the organization’s commitment to drug user activism. Third, we have likely underrepresented the perspectives of some PWID (e.g., those occupying different roles within the drug scene or with different individual characteristics). Notably, all but one of our participants self-identified as “straight” and our findings do not reflect the perspectives of lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer PWID. Further research is needed to disentangle the relationship between gendered violence and sexuality in drug scenes. Fourth, given that we relied upon self-reported data, it is possible that participants overstated or understated their experiences of violence. Fifth, given our focus on gendered violence, we may have overlooked other factors (e.g., drug debts) that perpetuated violence within the neighbourhood, and further research is needed that examines these dimensions. Finally, our research was undertaken in a neighbourhood that is distinct in many ways (e.g., large street-based drug scene and comprehensive harm reduction services), and the social geographies that we described may differ greatly from those in other street-based drug scenes.

Despite these limitations, our study demonstrates the critical role of gendered violence in restricting the geographies of both women and marginal men within the DTES, and underscores the need for environmental interventions that mitigate associated harms. Our findings indicate that there is an immediate need to scale up existing environmental supports and implement further targeted interventions to minimize violence among these highly-vulnerable PWID. Incorporating harm reduction services, including supervised injection services, into these interventions will be critical in promoting risk reduction.

Acknowledgements

We thank VANDU and study participants for their contribution to the research. We also thank current and present staff at the British Columbia Centre for Excellence in HIV/AIDS for their research and administrative support. The study was supported by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (MOP–81171) and the US National Institutes of Health (R01DA033147). Ryan McNeil is supported by the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council and Michael Smith Foundation for Health Research. Will Small and Thomas Kerr are supported by the Michael Smith Foundation for Health Research. Kate Shannon is supported by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research and Michael Smith Foundation for Health Research.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors report no conflicts of interest.

References

- Benoit C, Carroll D, Chaudhry M. In search of a healing place: Aboriginal women in Vancouver's Downtown Eastside. Social Science & Medicine. 2003;56(4):821–833. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(02)00081-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bourdieu P, Wacquant L. An invitation to reflexive sociology. Chicago: University of Chicago Press; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Bourgois P. In search of respect: Selling crack in el barrio. 2nd ed. Cambridge; New York: Cambridge University Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Bourgois P, Prince B, Moss A. The everyday violence of hepatitis C among young women who inject drugs in San Francisco. Human Organization. 2004;63(3):253–264. doi: 10.17730/humo.63.3.h1phxbhrb7m4mlv0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bourgois P, Schonberg J. Righteous dopefiend. Berkeley: University of California Press; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Braitstein P, Li K, Tyndall M, Spittal P, O'Shaughnessy MV, Schilder A, et al. Sexual violence among a cohort of injection drug users. Social Science & Medicine (1982) 2003;57(3):561–569. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(02)00403-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bungay V, Johnson JL, Varcoe C, Boyd S. Women's health and use of crack cocaine in context: Structural and ‘everyday’ violence. International Journal of Drug Policy. 2010;21(4):321–329. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2009.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canetto SS, Cleary A. Men, masculinities and suicidal behavior. Social Science & Medicine. 2012;74(4):461–465. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chermack ST, Blow FC. Violence among individuals in substance abuse treatment: The role of alcohol and cocaine consumption. Drug & Alcohol Dependence. 2002;66(1):29–37. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(01)00180-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clausen T, Waal H, Thoresen M, Gossop M. Mortality among opiate users: Opioid maintenance therapy, age and causes of death. Addiction. 2009;104(8):1356–1362. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2009.02570.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cleary A. Suicidal action, emotional expression, and the performance of masculinities. Social Science & Medicine. 2012;74(4):498–505. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Connell RW, Messerschmidt JW. Hegemonic masculinity: Rethinking the concept. Gender & Society. 2005;19(6):829–859. [Google Scholar]

- Cooper H, Moore L, Gruskin S, Krieger N. The impact of a police drug crackdown on drug injectors' ability to practice harm reduction: A qualitative study. Social Science & Medicine. 2005;61(3):673–684. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2004.12.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Courtenay WH. Constructions of masculinity and their influence on men's well-being: A theory of gender and health. Social Science & Medicine. 2000;50(10):1385–1401. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(99)00390-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curry A, Latkin C, Davey-Rothwell M. Pathways to depression: The impact of neighborhood violent crime on inner-city residents in Baltimore, Maryland, USA. Social Science & Medicine. 2008;67(1):23–30. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2008.03.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Certeau M. The Practice of Everyday Life. Berkely; Los Angeles: University of California Press; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Deering KN, Chettiar J, Chan K, Taylor M, Montaner JSG, Shannon K. Sex work and the public health impacts of the 2010 Olympic Games. Sexually Transmitted Infectious. 2012;88(4):301–303. doi: 10.1136/sextrans-2011-050235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duff P, Deering KN, Gibson K, Tyndall M, Shannon K. Homelessness among a cohort of women in street-based sex work: The need for safer environment interventions. BMC Public Health. 2011;11:643. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-11-643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Bassel N, Gilbert L, Wu E, Go H, Hill J. HIV and intimate partner violence among methadone-maintained women in New York City. Social Science & Medicine. 2005;61(1):171–183. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2004.11.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epele ME. Gender, violence and HIV: Women's survival in the streets. Culture, Medicine and Psychiatry. 2002;26(1):33–54. doi: 10.1023/a:1015237130328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fairbairn N, Small W, Shannon K, Wood E, Kerr T. Seeking refuge from violence in street-based drug scenes: Women's experiences in North America's first supervised injection facility. Social Science & Medicine. 2008;67(5):817–823. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2008.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farmer P. Pathologies of power: Health, human rights, and the new war on the poor. Berkeley: University of California Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Finlinson HA, Robles RR, Colón HM, Soto López M, del Carmen Negron M, Oliver-Vélez D, et al. Puerto Rican drug users experiences of physical and sexual abuse: Comparisons based on sexual identities. Journal of Sex Research. 2003;40(3):277–285. doi: 10.1080/00224490309552192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hough M, Natarajan M. Introduction: Illegal drug markets, research and policy. In: Hough M, Natarajan M, editors. Illegal drug markets: From research to policy. Monsey, NJ: Criminal Justice Press; 2000. pp. 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Hutton F. Risky business: Gender, drug dealing and risk. Addiction Research & Theory. 2005;13(6):545–554. [Google Scholar]

- Jewkes R, Morrell R. Sexuality and the limits of agency among South African teenage women: Theorising femininities and their connection to HIV risk practices. Social Science & Medicine. 2012;74(11):1729–1737. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.05.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerr T, Small W, Wood E. The public health and social impacts of drug market enforcement: A review of the evidence. International Journal of Drug Policy. 2005;16(4):210–220. [Google Scholar]

- Klein H, Levy JA. Shooting gallery users and HIV risk. Journal of Drug Issues. 2003;33(3):751–768. [Google Scholar]

- Krusi A, Chettiar J, Ridgway A, Abbott J, Strathdee SA, Shannon K. Negotiating safety and sexual risk reduction with clients in unsanctioned safer indoor sex work environments: A qualitative study. American Journal of Public Health. 2012;102(6):1154–1159. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2011.300638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lazarus L, Chettiar J, Deering K, Nabess R, Shannon K. Risky health environments: Women sex workers’ struggles to find safe, secure and non-exploitative housing in Canada’s poorest postal code. Social Science & Medicine. 2011;73(11):1600–1607. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.09.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maher L. Sexed work: Gender, race, and resistance in a Brooklyn drug market. Oxford; New York: Clarendon Press; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Maher L, Hudson SL. Women in the drug economy: A meta-synthesis of the qualitative literature. Journal of Drug Issues. 2007;37(4):805–826. [Google Scholar]

- Marshall BD, Milloy MJ, Wood E, Montaner JS, Kerr T. Reduction in overdose mortality after the opening of North America's first medically supervised safer injecting facility: A retrospective population-based study. Lancet. 2011;377(9775):1429–1437. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)62353-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marshall BDL, Fairbairn N, Li K, Wood E, Kerr T. Physical violence among a prospective cohort of injection drug users: A gender-focused approach. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2008;97(3):237–246. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2008.03.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mehta A. Embodied discourse: On gender and fear of violence. Gender, Place & Culture: A Journal of Feminist Geography. 1999;6(1):67–84. [Google Scholar]

- Nasir S, Rosenthal D. The social context of initiation into injecting drug sin the slums of Makassar, Indonesia. International Journal of Drug Policy. 2009;20(3):237–243. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2008.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ouellet LJ, Jimenez AD, Johnson WA, Wiebel WW. Shooting galleries and HIV disease: Variations in places for injecting illicit drugs. Crime & Delinquency. 1991;37(1):64–85. [Google Scholar]

- Pain RH. Social geographies of women's fear of crime. Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers. 1997;22(2):231–244. [Google Scholar]

- Peralta R. College alcohol use and the embodiment of hegemonic masculinity among European American men. Sex Roles. 2007;56:741–756. [Google Scholar]

- Petrar S, Kerr T, Tyndall MW, Zhang R, Montaner JSG, Wood E. Injection drug users' perceptions regarding use of a medically supervised safer injecting facility. Addictive Behaviors. 2007;32(5):1088–1093. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2006.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhodes T, Watts L, Davies S, Martin A, Smith J, Clark D, et al. Risk, shame and the public injector: A qualitative study of drug injecting in south wales. Social Science & Medicine. 2007;65(3):572–585. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2007.03.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhodes T. Risk environments and drug harms: A social science for harm reduction approach. International Journal of Drug Policy. 2009;20(3):193–201. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2008.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheper-Hughes N. Death without weeping: The violence of everyday life in Brazil. Berkeley: University of California Press; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Shannon K, Kerr T, Strathdee SA, Shoveller J, Montaner JS, Tyndall MW. Prevalence and structural correlates of gender based violence among a prospective cohort of female sex workers. BMJ. 2009;339:b2939. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b2939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shannon K, Rusch M, Shoveller J, Alexson D, Gibson K, Tyndall MW. Mapping violence and policing as an environmental-structural barrier to health service and syringe availability among substance-using women in street-level sex work. International Journal of Drug Policy. 2008a;19(2):140–147. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2007.11.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shannon K, Kerr T, Allinott S, Chettiar J, Shoveller J, Tyndall MW. Social and structural violence and power relations in mitigating HIV risk of drug-using women in survival sex work. Social Science & Medicine. 2008b;66(4):911–921. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2007.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Small W, Krusi A, Wood E, Montaner J, Kerr T. Street-level policing in the downtown eastside of Vancouver, Canada, during the 2010 Winter Olympics. International Journal of Drug Policy. 2012;23(2):128–133. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2011.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Small W, Rhodes T, Wood E, Kerr T. Public injection settings in Vancouver: Physical environment, social context and risk. International Journal of Drug Policy. 2007;18(1):27–36. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2006.11.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stoudt BG. “You’re either in or you’re out”: School violence, peer discipline, and the (re)production of hegemonic masculinity. Men and Masculinities. 2006;8(3):273–287. [Google Scholar]

- Strathdee SA, Patrick DM, Currie SL, Cornelisse PGA, Rekart ML, Montaner JSG, et al. Needle exchange is not enough: Lessons from the Vancouver injecting drug use study. AIDS. 1997;11(8):F59–F65. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199708000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valentine G. The geography of women's fear. Area. 1989;21(4):385–390. [Google Scholar]

- Vlahov D, Wientge D, Moore J, Flynn C, Schuman P, Schoenbaum EE. Violence among women with or at risk for HIV infection. AIDS & Behavior. 1998;2(1):53–60. [Google Scholar]

- Wood E, Kerr T. What do you do when you hit rock bottom? Responding to drugs in the City of Vancouver. International Journal of Drug Policy. 2006;17(2):55–60. [Google Scholar]