Abstract

Building on recent European studies, we used the Survey of Income and Program Participation to provide the first analysis of fertility differences between groups of U.S. college graduates by their undergraduate field of study. We used multilevel event-history models to investigate possible institutional and selection mechanisms linking field of study to delayed fertility and childlessness. The results are consistent with those found for Europe in showing an overall difference of 10 percentage points between levels of childlessness across fields, with the lowest levels occurring for women in health and education, intermediate levels for women in science and technology, and the highest levels for women in arts and social sciences. The mediating roles of the following field characteristics were assessed: motherhood employment penalties; percentage of men; family attitudes; and marriage patterns. Childlessness was higher among women in fields with a moderate representation of men, less traditional family attitudes, and late age at first marriage.

Keywords: childlessness, delayed childbearing, education, fertility, field of study

Introduction

The fertility patterns of U.S. college graduates are increasingly distinct from those of women with lower levels of education. Whereas women of all education levels have postponed marriage, only college-educated women have delayed childbirth to the same extent as marriage (Ellwood and Jencks 2004; McLanahan 2004). The gap in age at first birth has grown, and by the end of their reproductive years, college-educated women are more likely to be childless and have fewer children overall (Rindfuss et al. 1996; Martin 2004; Musick et al. 2009). Investigators of family formation processes in the United States have tended to focus on the early childbearing of women with the lowest levels of education (e.g., Ribar 1999; Furstenberg 2003; Carlson et al. 2004; Edin and Kefalas 2005), and there has been relatively little research on the pattern of later and lower fertility that is characteristic of U.S. college graduates. The continuing increase in college enrolments among women in the U.S. and other advanced industrialized countries (Buchmann and DiPrete 2006; Bhrolchain and Beaujouan 2012) makes it important to obtain a better understanding of variation in the effects of college study on family life.

Different fields of undergraduate study lead to career trajectories that differ in their economic rewards, demands, and the relative importance of employment and family. For this reason, field of study might be expected to be an important factor in explaining fertility variation among college graduates, and research in Europe has already begun to explore this association (Lappegård 2002; Lappegård and Rønsen 2005; Hoem et al. 2006a, 2006b; Martín-García and Baizán 2006; Neyer and Hoem 2008; Van Bavel 2010). Studies there find that fertility is indeed highly stratified by field of study. Subsequent childbearing is at least as closely associated with field of study as level of education in Norway (Lappegård 2002; Lappegård and Rønsen 2005), Spain (Martín-García and Baizán 2006), and Sweden (Hoem et al. 2006a, 2006b). To our knowledge, no systematic investigation of links between field of study and fertility has been undertaken in the United States.

In the study reported in this paper, we built on recent European research with the aim of obtaining a better understanding of variation in the fertility patterns of U.S. college-educated women. The expansion of women’s educational attainment and employment in the United States and Europe has unfolded in different labour markets and has been subject to different social policies. European welfare regimes are relatively generous in their support of women’s labour force participation, with such provisions as paid family leave, subsidized child care, and part-time work (Gornick et al. 1997; Waldfogel 2001; Gornick and Meyers 2003). The United States ranks low in work-family support policies, but there may be trade-offs in greater flexibility in labour markets, gender equality in access to jobs and pay, and cheaper private-sector child care (Morgan 2005; Mandel and Semyonov 2006; Pettit and Hook 2009; Mandel and Shalev 2009a, 2009b). These trade-offs may favour college graduates (Mandel and Shalev 2009a, 2009b; Mandel 2010). Despite weak support policies, labour force attachment and fertility rates in the U.S. remain high relative to those in Europe (Brewster and Rindfuss 2000; Morgan 2003; Morgan 2005; Misra et al. 2011).

We drew on large, nationally representative samples from the 2001, 2004 and 2008 Survey of Income and Program Participation (SIPP) to provide the first analysis of fertility differences between groups of U.S. college graduates by their undergraduate field of study. We used multilevel event-history models to investigate potential mechanisms linking field of study to delayed fertility and childlessness. To explore institutional and selection processes, our models included the following indicators: motherhood employment penalties; percentage of men in the field; early marriage (as measured by the SIPP); and early attitudes about family roles (as measured by the National Longitudinal Survey of Youth 1979, (NLSY79)).

Background

How might field of study matter?

A growing line of research focuses on the potential importance of institutional accommodations in easing the competing demands of work and family on women’s time (Bianchi 2000; Joshi 2002; DiPrete et al. 2003; Morgan 2003; Rindfuss et al. 2003; Morgan and Taylor 2006). The idea is that the easier it is for women to combine motherhood and employment–rather than having to choose between them–the weaker the constraints on childbearing. Indeed, at the aggregate level, the long-held negative relationship between women’s labour force participation and completed fertility has reversed in developed countries: high rates of women’s participation in the labour force are now associated with high fertility (Brewster and Rindfuss 2000; Billari and Kohler 2004).

Conditions that reduce work-family conflict include greater flexibility and smaller penalties for time spent outside the labour force (England 1992; Glass and Camarigg 1992; Goldin and Katz 2008b). We assessed workplace accommodations by measuring the differences in labour force participation between mothers with children aged under five, and all other women, by their field of study. We postulated that fields of study leading to jobs with smaller motherhood employment penalties would impose fewer constraints on childbearing and result in earlier and higher overall fertility.

Institutional perspectives suggest causal mechanisms linking field of study and family formation pattern, but there are undoubtedly also selection processes at work. Hakim (2000) has emphasized the importance of heterogeneity in women’s lifestyle preferences–particularly the degree to which women are home or work-centred–for understanding women’s fertility decisions. She makes the following proposals: ‘home-centred’ women obtain education as a form of social capital; ‘work-centred’ women invest heavily in training geared specifically to careers; and a middle group of ‘adaptive’ women obtain education with a view to working, although investing less than the ‘work-centred’. The ‘adaptive’ group might particularly be expected to select fields of study based on their perception of the ease of balancing work and family obligations in the jobs characteristic of those fields. The extent to which women are family-centred may also be associated with individual characteristics. For example, a nurturant attitude and a preference for working with people might select women into such caring or helping professions as teaching, health, and social work (Fortin 2008; Folbre 2010). These selection processes may be reflected in the gender composition of fields and attitudes about family roles typical in them.

Any effects of field of study on fertility may be indirect, working through variation in age at marriage. Fertility remains closely associated with marriage among U.S. college graduates, with only 7 per cent of births in this group occurring outside marriage (Kennedy and Bumpass 2011). Consequently, differences in marriage rates across fields of study may be a key factor in shaping variation in childlessness. Fields of study associated with less stable career trajectories or lengthier training periods may delay marriage (Oppenheimer et al. 1997), as might fields with weaker ties to particular jobs (Hoem et al. 2006b). Further, fields of study may provide different opportunities for marriage, either promoting or inhibiting it. For example, fields in which a high proportion of students are men may shape marriage prospects via the availability of prospective partners, with more prospective partners leading to earlier marriage and, in turn, childbearing. This suggests that the percentage of men in a field may reflect more than selection into fields; it also points to potential nonlinearities in the relationship between percentage of men and childbearing.

Previous research

A handful of studies in Europe have explored the association between field of study and fertility. Hoem et al. (2006a, 2006b) found that Swedish women who studied health and teaching had lower rates of childlessness and higher overall fertility than women who studied in other fields. Similarly, studies in Austria (Neyer and Hoem 2008), Norway (Lappegård 2002; Lappegård and Rønsen 2005), and Spain (Martín-García and Baizán 2006) all found earlier and higher overall fertility among women in fields of study related to caring or helping professions. As a factor in differentiating fertility, field of study generally seems to be equally or more important than educational level. For example, among Swedish women with the equivalent of a college degree, 10 per cent of those who had graduated in health and teaching were childless, whereas the largest proportion childless amongst all other fields of study was 30 per cent, a difference of 20 percentage points. The maximum difference in childlessness across educational levels was only 5 percentage points (13 per cent among those with less than a high school education and 18 per cent among those with high tertiary education, or college degrees). In contrast, among U.S. women aged 40–44 in 2008, the difference in childlessness across educational levels was substantially higher at 9 percentage points: 15 per cent of those without a high school degree were childless, compared with 24 per cent of those with a college degree (U.S. Census Bureau 2010).

European data show that childlessness is highest among women who studied the arts and humanities, followed by those who studied the social sciences, and mid-range for women in science and technology (Lappegård 2002; Hoem et al. 2006b; Neyer and Hoem 2008). There is much concern in the U.S. over the small proportion of women in science and technology, and considerable debate over how family roles and preferences influence behaviour (Ceci and Williams 2007; Ceci et al. 2009; Sassler et al. 2011; Morgan et al. 2013). Women graduating in disciplines with large concentrations of men are generally more likely to remain childless and tend to have fewer births on average, although there are exceptions. Hoem et al. (2006b) has suggested that the relatively weak ties to future occupations in the arts and humanities (which typically offer no special job training or teaching qualifications) might explain the high rates of childlessness in these fields, despite their relatively high levels of female representation. How the fertility experiences of U.S. women in science and technology fields compare with those of European women is unknown.

Van Bavel (2010) further explored how field of study relates to fertility postponement across 21 European countries, focusing on percentage of men, family attitudes, and earnings potential as mechanisms linking field of study to fertility. Using multilevel conditional probability models with women cross-classified by country and field of study, his analysis found childbearing at earlier ages among those who had graduated in fields of study characterized by a higher representation of women and more traditional family attitudes. It also found later childbearing among women in fields of study with higher earnings potential (as indicated by the expected starting wage and the steepness of the rise in earnings with age), a finding consistent with the hypothesis that higher wages mean higher income forgone in the event of childbirth, and thus higher opportunity costs of having children. While wages were a significant factor in Van Bavel’s study of women across educational levels and countries, we expected them to play a weaker role in differentiating fertility by field of study among our sample of U.S. college graduates, for whom wages were relatively homogeneous (this was borne out by sensitivity tests that included information on wages by field of study).

In sum, evidence from Europe suggests that fertility differences by field of study are driven by a mixture of both causal and selection effects. That is, field of study appears to have a causal effect on attitudes and career prospects (and, in turn, fertility behaviour), and women appear to be selected into fields of study by their attitudes about family life. Women’s attitudes evolve with age and experience (Thornton et al. 1983; Fan and Marini 2000), and Van Bavel’s measure of family attitudes was assessed while men and women were in college, when their attitudes were possibly already shaped by the different social environments of fields of study.

We know of no general investigation of the relationship between undergraduate field of study and fertility in the U.S. The closest is work by Goldin and colleagues, which documented fertility differences among elite college graduates by advanced degree and career trajectory. Comparing three cohorts of women who had graduated from Harvard with advanced degrees, they found that family size was generally smallest for those with a doctorate, and largest for physicians (Goldin and Katz 2008b). Physicians took the shortest time off after having a child and experienced the smallest loss of earnings for time off. Goldin reported similar results from the College and Beyond data, which included graduates who entered a broader set of selective colleges in 1976 (Goldin 2006). She and Katz concluded (2008b, p.7) that ‘women in careers with the greatest predictability and the smallest financial penalty for time out have the most children’. Characteristics of careers are more directly related to the factors that could ease or exacerbate work-family conflict than fields of study. At the same time, careers are established much further into the life course, and decisions about what job to take or even whether to work may be affected by family formation. Our focus on field of study allows us to examine part of the career process that takes place well before the birth of the first child for the vast majority of college graduates.

Given the lack of research on the relationship between field of study and fertility in the U.S., how might one expect that relationship to compare with the findings for Europe? As noted above, the United States ranks low relative to Europe in work-family support policies, such as paid leave and subsidized child care, but high in labour market flexibility (e.g., Gornick and Meyers 2003; Mandel and Semyonov 2006). An unintended consequence of paid-leave policies appears to be lower wages and greater occupational segregation by gender, which disproportionately affect highly skilled women (Mandel 2010; Misra et al. 2011). The prospect of motherhood may thus be less constraining to U.S. college graduates than to their counterparts in the more developed welfare states of Western Europe. The U.S. educational system is also less rigid, lacking the strong vocational and apprenticeship programmes of many of the European systems (Goldin and Katz 2008a; Mandel and Shalev 2009). The more general approach to education and to the greater overall flexibility in job opportunities in the United States suggest that fields of study there might be less tied to specific occupational characteristics, potentially resulting in smaller differences in fertility patterns among undergraduate fields of study.

Our approach

We explored how field of study relates to fertility delay and childlessness among U.S. college-educated women, relying primarily on data from the SIPP. Our investigation of potential mechanisms linking field of study to fertility included measures of selection processes discussed in past European work, as well as indicators of institutional accommodations not examined elsewhere. Our analyses focused on college graduates because there is little educational specialization before college enrolment in the U.S. (the European studies mentioned above included women of different education levels). Data from the SIPP were available on the timing of first births to women only, precluding analysis of men’s fertility. The SIPP was well suited to our study, with samples large enough to investigate variation by field of study and also to provide detailed information on fertility, education, earnings, employment, and marriage.

We start with a descriptive background and then explore the potential factors linking field of study with family formation. We estimated discrete-time multilevel event-history models of first birth among women aged 20–48 as a function of individual-level socio-demographic variables and field-of-study-level characteristics. Most of the latter were generated from data on women aged 21–55 years in the SIPP, including motherhood employment penalties, percentage of men, and early marriage. Family-role attitudes were assessed using data from the NLSY79, a panel survey of 14–21-year-olds that began in 1979. Attitudes were observed at the first wave of data collection, before college enrolment for most, and thus largely before respondents were influenced by their experiences in particular fields. Thus we had a relatively good measure of attitudes as a selection factor into fields of study. We further explored the role of differences across fields in marriage timing (per cent married by age 26) in explaining differences in the timing of first births. Finally, we used our model results to predict how the proportion childless would change when varying field-of-study-level characteristics.

Our data and modelling approach allowed us to examine the institutional, selection, and intervening variables factors outlined earlier. These were our starting hypotheses: (1) Institutional accommodations that reduce the cost of combining motherhood with employment may weaken constraints on childbearing, implying that smaller motherhood employment penalties are positively associated with the transition to a first birth. (2) Women may select into fields of study on the basis of characteristics that also predict earlier transitions to motherhood; for example, traditional family values may lead to earlier first births and draw women to the (female-dominated) caring and helping fields. The percentage of men in a field may further reflect partner availability, potentially resulting in nonlinearities in the relationship between field of study and fertility. (3) Marriage timing may play a mediating role in the link between field of study and fertility; in particular, the proportion of women married by age 26 is likely to be associated with earlier births. These processes need not be competing; each may be occurring simultaneously, some potentially offsetting, and others reinforcing. Of course, our measures are only rough proxies; we discuss their limitations in greater detail in the discussion section.

Data and method

Survey of Income and Program Participation

The SIPP is a multi-part survey conducted in the U.S. every four months through in-person interviews with all individuals aged over 15 in the household (U.S. Census Bureau 2009). For the rounds of the survey we used, the number of households and the periods over which they were tracked were as follows: 36,700 over 36 months in 2001; 46,500 over 48 months in 2004; 52,000 households over 40 months in 2008. The primary purpose of the SIPP is to gather information about sources of household income, but information on specific topics is also collected in separate modules. We relied on the second module for retrospective fertility and marital histories. Also included in the module were details of schooling, including degrees attained, timing of degree completion, and characteristics of educational programmes. SIPP person-weights account for differential non-response and panel attrition and were applied in all descriptive analyses.

We restricted our analysis to women respondents born 1960–79 (aged 20–48 at interview) who had completed a four-year college degree by age 25 and were childless at the completion of their degree. (Characteristics of the field of study were generated from more general samples, described in greater detail below). Excluding women who did not finish their degree by age 25 resulted in a loss of about 15 per cent of the sample of women with college degrees, and excluding those who had their first child before completing their degree resulted in an additional loss of 5 per cent. These exclusions resulted in a sample of women with college degrees who were slightly more educationally advantaged than the overall population of women with college degrees, which somewhat limited the representativeness of our results, but ensured that the field of study was completed before the first birth. Pooling sample numbers from the 2001, 2004 and 2008 SIPPs yielded a total sample of 8,895 women. We transformed the dataset into a file of person-years at risk for our event-history analysis, with one record for every year of age from degree to first birth, giving a total of 79,664 person-years.

The 1960–79 birth cohort provided a large sample of women with college degrees and allowed us to follow some to the end of their fertile years. At the same time, this 20-year span represents a fairly recent snapshot of college graduates and their fertility. The oldest of them were coming of age in the late 1970s, when increases in college enrolment, labour force participation, fertility postponement, and childlessness were well under way (Bianchi 2000; Martin 2004; Goldin et al. 2006). We did not consider earlier cohorts whose experiences in school, work, and family were quite different (Goldin 2004).

National Longitudinal Survey of Youth (NLSY79)

The NLSY79 is a nationally representative panel survey that has followed nearly 13,000 men and women aged 14–21 in 1979, representing the 1958–65 birth cohort (U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics 2008). The NLSY79 includes attitudinal questions that are not in the SIPP, but the sample sizes are considerably smaller (with just 1,258 women college graduates), making it difficult to examine fertility patterns even for broad fields of study. Supplementing our main data file with data on attitudes by field of study from the NLSY79 allowed us to combine its detail with the large samples of the SIPP. We used a sample of 3,572 women who reported a college field of study by the 2008 wave. We aggregated the more detailed fields of study reported in the NLSY79 to match SIPP definitions.

Measures

Fertility

Women aged over 15 were asked the number of children ever born and the year of their first and most recent births. Lacking information on the timing of men’s fatherhood or women’s intermediate births (between the first and the most recent), our analysis was restricted to women’s first births.

Field of study

Individuals who had completed a bachelor’s degree indicated which of 18 major fields of study they had undertaken in school. We eliminated individuals in the pre-professional fields of study, whose numbers were too small to analyse separately. We included data on the remaining 17 specific fields of study in our final models to maximize variation but aggregated them into 7 broader categories to present descriptive patterns: arts and humanities; education; general studies; health sciences; private and public administration; science and technology; and social sciences (see detailed description of fields in the Appendix). These broad categories are consistent with definitions from past work (Hoem et al. 2006a, 2006b; Neyer and Hoem 2008; Van Bavel 2010). One limitation with this categorization, also pointed out in European studies, is that we were able to identify women in teaching only if they had graduated in education. It is possible that women in other fields, such as history or English, subsequently attained teaching qualifications.

Characteristics of field of study

We aggregated the data on working-age college graduates (aged 21–55) from the 2001, 2004, and 2008 SIPPs to generate all the field-of study-level variables except family-role attitudes (which we derived from the NSLY79). The ‘motherhood employment penalty’ was measured as the difference between the percentage of labour force participation of mothers with children aged under five and that of women with no children under five. Percentage of men was measured simply as the percentage of men having graduated in a given field of study, and we included the squared percentage of men in the field as well to allow for a curvilinear association between percentage of men in the field and women’s fertility. Finally, the timing of early marriage was assessed by the percentage of women married by age 26.

We derived a measure of family-role attitudes specific to field of study from NLSY79 women reporting a field of study. Relevant questions were asked in 1979 and 1982; we relied on the answers to the 1979 questions but substituted 1982 responses if missing. Respondents were asked to indicate their agreement with the following, ranging from 1 = strongly disagree, to 4 = strongly agree: a woman’s place is in the home, not the office or shop; a wife with a family has no time for outside employment; employment of wives leads to more juvenile delinquency; it is much better if the man is the achiever outside the home and the woman takes care of the home and family; men should share the work around the house with women; and women are much happier if they stay home and take care of children. We reverse-coded the item referring to men sharing work around the house, omitted individuals who failed to answer 3 or more of the 6 items, and averaged over given answers to produce an index of traditional family-role attitudes (Cronbach’s α = 0.91), with higher values corresponding to more traditional family-role attitudes. We used the standardized version of this index in the multivariate models to facilitate interpretation, so that change was measured in standard-deviation units. Because this measure came from a different survey with smaller sample sizes than the main survey, it was probably measured with more error, which may attenuate estimated effects. Women in the NLSY79 sample were also slightly older than the women in our main sample. As attitudes were becoming more progressive over this period (Thornton et al. 1983), we may have captured somewhat more traditional family-role attitudes in data from the NLSY79. Nonetheless, barring rapid differential change in attitudes across fields, our measure should capture relevant differences between fields of study. Finally, we used a larger sample of college-goers (3,572), rather than of college graduates (1,258), to estimate family-role attitudes for each field of study, so providing more stable estimates; the results were not sensitive to this slight change in definition.

Individual-level demographic controls

We generated time-invariant indicators of the respondent’s race and ethnicity: non-Hispanic White; non-Hispanic Black; and Hispanic. We also constructed a time-invariant quantitative variable for the year in which the respondent obtained her bachelor’s degree to account for cohort differences in fertility patterns.

Multilevel event-history model

We examined the timing of first birth with a discrete-time multilevel event-history model that nests individual person-years within field of study. Our baseline duration was a function of age, specified as categories to allow for flexibility in fertility patterns by age: 20–24; 25–29; 30–34; 35–39; and 40 and over. All models included time-invariant individual-level controls (race/ethnicity and year of degree) and field-of-study-level motherhood employment penalties, percentage of men, and family-role attitudes. Some models included field-of-study-level indicators of marriage timing. The model used can be written as a basic logistic function, in terms of the log odds of a first birth:

| (1) |

where pijt is the probability that individual i, in field of study j, has a first birth in person-year t; At is a vector representing the five age categories specified above; Xij is a vector representing our time-invariant individual-level controls; and Zj is a vector of field-level characteristics. These covariates are represented by fixed slopes γ1, γ2, and γ3, respectively. The element γ00 is an overall intercept term, and ν0j is a field-specific random error term with variance , intended to capture heterogeneity across fields of study unexplained by our covariates (Teachman 2011).

We generated model-based predicted probabilities to illustrate results in a more intuitive way than is possible with logits or odds ratios. Applying the estimated coefficients and sample means to a transformation of equation (1), we calculated age-specific predicted probabilities of first birth. We then multiplied these conditional probabilities together to yield the predicted probability of ever having a first birth–the complement being the probability of being childless. In this way, we can show differences in both the timing and incidence of childbearing across fields of study. Using results from full models pooled over fields of study, we altered the values of the field-of-study-level covariates to simulate variation in the proportions permanently childless. These simulations add further detail to the substantive key findings.

Results

Descriptive results

First birth timing and incidence

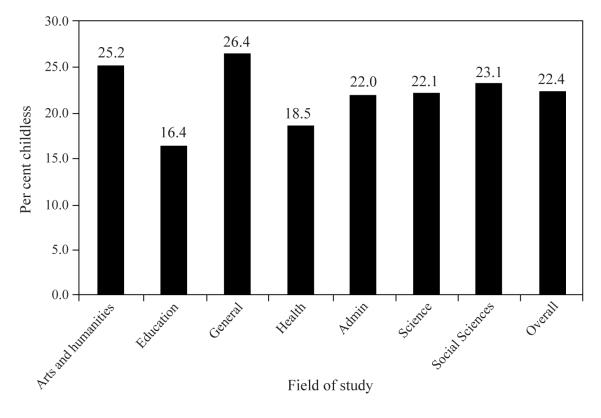

We ran field-of-study-specific discrete-time event-history models of first birth to explore differences in the timing of fertility among women using our main sample (timely college graduates born 1960–79, aged 20–48 at interview, and childless on graduating). We regressed the logit of first birth on a cubic term for age to impose some structure on our descriptive results (weighting models and including no other controls). We used model estimates as described above to generate predicted age-specific probabilities of first birth. Figure 1 shows predicted probabilities of childlessness at age 44 by field of study. The smallest predicted probabilities of childlessness occur for women in education and health, at 16.4 and 18.5 per cent, respectively. The largest probabilities occur for women in the arts and humanities (25.2) and general studies (26.4 per cent). Childlessness among women in administration (22 per cent), science and technology (22.1 per cent), and social sciences (23.1 per cent) take intermediate values. Differences are generally statistically significant across these three groupings, and overall patterns are similar to those found in Europe. The overall predicted rate of childlessness is 22.4 per cent. This estimate is reasonably close to the value of 24 per cent for the proportion childless among U.S. college graduates, as estimated from the CPS (U.S. Census Bureau 2010). The difference between the two estimates reflects differences in measurement; in our study, the probability is a period-based estimate derived by cumulating age-specific rates of first birth over the childbearing years, whilst the estimate derived from the CPS is a cohort one, based on completed fertility of women aged 40-44 in 2008. (The estimate derived in the present study therefore reflects the fertility of slightly earlier cohorts).

Figure 1.

Predicted probabilities of childlessness by field of study, derived from field-specific discrete time event-history models of first birth, U.S. graduate women born 1960–79

Note: Separate, weighted models run for each field of study. Logit of first birth regressed on cubic function of age.

Sources: 2001, 2004, and 2008 Survey of Income and Program Participation, sample of women graduates with no children at timely degree completion.

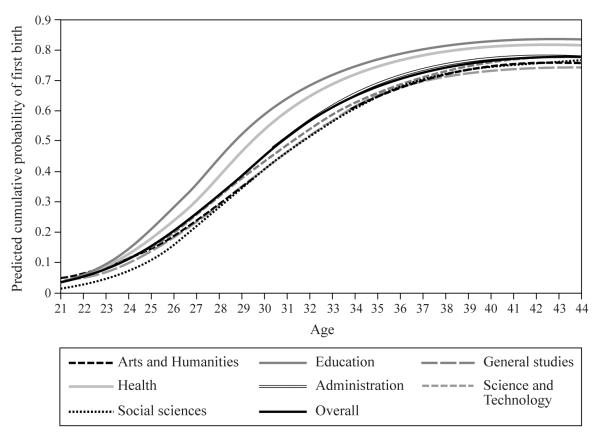

Figure 2 gives more detail on how age-specific rates of first birth cumulate to provide estimates of the eventual proportions with children, and those without them, at age 44. Women in education and health make the earliest transitions to first birth, with higher birth probabilities than other college graduates until their early 30s, when probabilities fall and attain a rate of increase similar to that of other fields of study. Still, because these women start childbearing earlier, they remain more likely than others to have had a child at each age and less likely to be childless at age 44. Women who studied science and technology and public administration appear to have low probabilities of first births early on but relatively high probabilities in their mid to late 30s, resulting in moderate levels of childlessness. Women who completed degrees in arts and humanities also have fewer births in the early years, but without any obvious ‘catch up’ later. From regression models (not reported here), we found that women in science and administration have a significantly smaller chance of having a first birth than women in education, but only for ages under 30. In contrast, women in all other fields of study have significantly smaller chances at all ages of having a first birth than women in education.

Figure 2.

Cumulative predicted probabilities of first birth for U.S. graduate women by age and field of study, derived from field-specific discrete time event-history models of first birth, U.S. graduate women born 1960–79

Note: Separate, weighted models run for each field of study. Logit of first birth regressed on cubic function of age.

Sources: 2001, 2004, and 2008 Survey of Income and Program Participation, sample of women graduates with no children at timely degree completion.

Field characteristics

Table 1 summarizes the key characteristics of the different fields of study that might account for the association between field of study and fertility: motherhood employment penalties; percentage of men; and traditional family attitudes.

Table 1.

Characteristics of fields of study of U.S. women graduates (from SIPP) and fields of study of women completing some U.S. college (from NLSY79), women born 1960–79

| Arts and humanit ies |

Educati on |

General studies |

Health sciences |

Private and public administrat ion |

Science and technol ogy |

Social sciences |

Overall | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

2001, 2004, 2008 Survey of Income and Program

Participation | ||||||||

| Motherhood employment penalty |

15.70 | 12.30 | 13.90 | 9.20 | 15.80 | 15.20 | 16.30 | 14.00 |

| Per cent men | 42.20 | 22.90 | 50.20 | 20.70 | 55.80 | 70.60 | 36.70 | 50.2 |

| Per cent of women married by 26 |

37.00 | 54.40 | 37.20 | 46.40 | 39.00 | 39.80 | 37.20 | 41.4 |

|

1979 National Longitudinal

Survey of Youth |

||||||||

| Traditional family attitudes | 1.92 | 1.98 | 1.88 | 1.98 | 1.92 | 1.86 | 1.85 | 1.92 |

| Number of Observations | ||||||||

| (NLSY) | 294 | 406 | 194 | 590 | 1200 | 534 | 354.0 | 3572 |

| Number of Observations (SIPP) | 2,586 | 3,100 | 3,166 | 1,527 | 3,555 | 2,183 | 2,103 | 18,220 |

Note: Motherhood employment penalty was calculated as the difference in labour force participation rates between women with children under the age of five and all other women in each field. Per cent men and motherhood employment penalty were calculated using 2001, 2004 and 2008 SIPP samples of college graduates aged 21–55. Attitudes from the NLSY79were measured in 1979, when individuals were 14–21 years old. 1982 attitudes were used when 1979 values were missing.

Source: 2001, 2004, and 2008 Survey of Income and Program Participation (SIPP) and the 1979 National Longitudinal Survey of Youth (NLSY79). SIPP women aged 21–55 who had obtained at least a bachelor’s degree by SIPP interview. NLSY79 women aged 14–21 in 1979 who had completed at least some college course by the 2008 interview

If those fields of study associated with higher fertility (i.e., education and health) are more accommodating of a work-family balance, we would expect to see smaller employment penalties for having young children, i.e., a smaller gap in employment between mothers with young children and other women. The data partly confirm this expectation: the penalty is smallest for health (9.2 percentage points), followed by education (12.3 percentage points). The education and health fields of study are heavily dominated by women (sixth row, Table 1), with men accounting for only 22.9 and 20.7 per cent of degrees, respectively. In contrast, the science and technology field is heavily dominated by men, who earn 70.6 per cent of such degrees. Except for the difference between education and health, all differences in percentage of men among broad fields are statistically significant. We found that the percentage of men in a given field of study correlated positively with traditional family-role attitudes characteristic of the field, with education and health (the most women-dominated fields) also scoring highest on traditional attitudes (1.98). Women in general studies, private and public administration, science and technology, and social sciences are all significantly less traditional than women on average in their family attitudes. Finally, women in education and health were more likely to be married by age 26: 54.4 and 46.4 per cent, respectively. These figures are significantly higher than the 37 to 39 per cent of women married by age 26 in all other fields, consistent with the earlier first births and lower levels of childlessness in education and health.

Multivariate results

Table 2 gives the odds ratios from our discrete-time multilevel event -history models. Odds ratios indicate how changes in a given covariate are associated with changes in the odds of having a first birth, with values above 1 indicating a positive association and those below 1 a negative association. The top panel shows covariates at the individual level, including age, degree year, and race and ethnicity. The bottom panel shows field-of-study-level characteristics for 17 specific fields (rather than the 7 broad fields used in our descriptive summary, above). Table 2 presents the results of three models: Model 1 includes only demographic information at the individual level, Model 2 includes our key field-of-study-level variables, and Model 3 adds indicators of early marriage. All models include a random effect at the field-of-study level to allow for unobserved correlations within fields of study, and the associated standard deviation (shown at the bottom of Table 2) represents heterogeneity across fields unexplained by controls.

Table 2.

Odds ratios of individual and field-of-study characteristics associated with having a first birth, from discrete-time event-history models, U.S. graduate women born 1960–79, aged 21–48

| M1: Demographics |

M2: Field characteristics |

M3: Full model | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Individual characteristics | |||

| Degree year | 0.998 (0.003) |

0.998 (0.003) |

0.998 (0.003) |

| Race (White non-Hispanic reference group) | |||

| Black, non-Hispanic | 0.957 (0.058) |

0.960 (0.058) |

0.963 (0.058) |

| Hispanic | 1.289 *** (0.105) |

1.290 *** (0.105) |

1.290 *** (0.105) |

| Age 20-24 | 0.207 *** (0.010) |

0.207 *** (0.010) |

0.207 *** (0.010) |

| Age 25-29 | 0.652 *** (0.022) |

0.652 *** (0.022) |

0.652 *** (0.022) |

| Age 30-34 (reference) | |||

| Age 35-39 | 0.648 *** (0.037) |

0.647 *** (0.037) |

0.647 *** (0.037) |

| Age 40 and over | 0.184 *** (0.026) |

0.184 *** (0.026) |

0.184 *** (0.026) |

| Field-of-study characteristics | |||

| Motherhood employment penalty | 1.000 (0.008) |

1.000 (0.006) |

|

| Per cent men | 0.974 *** (0.007) |

0.998 (0.007) |

|

| Per cent men squared | 1.000 *** (0.000) |

1.000 (0.000) |

|

| Per cent women married by age 26 | 1.020 *** (0.004) |

||

| Traditional family attitudes (from NLSY79) | 1.058 ** (0.025) |

1.042 ** (0.019) |

|

| Random effects intercepts | |||

| Field of study (standard deviation) | (0.143) | (0.078) | (0.023) |

| Wald Chi squared (df) | 1123.9 | 1142.75 | 1239.91 |

| Observations | 79,664 | 79,664 | 79,664 |

Note: Family attitudes are based on 6 questions in the 1979 National Longitudinal Survey of Youth about attitudes towards family roles. See text for description of questions. Scale runs from 1–4 with higher values indicating more traditional family-role attitudes. The measure was then standardized for ease of interpretation. A one-unit increase in the traditional family-role attitudes represents a one standard deviation increase in traditonal family-role attitudes.

p < 0.10

p <. 0.05

p < 0.01

Source: 2001, 2004 and 2008 Survey of Income and Program Participation, sample of women graduates with no children at timely degree completion, born 1960–79.

Socio-demographic variables in Model 1 operate as expected (and change little across models): the odds of a first birth are largest for women aged 30 to 34, and Hispanic graduates are 1.3 times more likely to have a first birth at any given age than non-Hispanic Whites (with the odds for Blacks being statistically insignificantly different from those for Whites). Adding characteristics of the fields of study in Model 2, we find that motherhood employment penalties are not significantly associated with the odds of having a first birth: that is, our measure of work-family inflexibility does not, contrary to our expectation, appear to constrain family formation. Model 2 shows a statistically significant association between the percentage of men in a given field of study and the odds of a first birth. The association, however, is not linear: the results for the percentage of men suggest that the concentration of men in a field of study is negatively associated with the probability of having a first birth, but that the strength of the association declines at higher concentrations. As expected, we also find a positive association between traditional family attitudes and first-birth probabilities. A one-standard-deviation increase in traditional attitudes is associated with a 6 per cent increase in the odds of a first birth.

Finally, Model 3 adds the indicator for marriage timing for each field of study, to examine the extent to which field characteristics are associated with fertility through the intervening life event of marriage. Not surprisingly, the proportion married by age 26 is positively associated with the odds of having a first birth. After accounting for the timing of marriage, the coefficient on the percentage of men in the field of study becomes statistically insignificant, and the coefficient for traditional family attitudes becomes smaller (although remaining statistically significant). These findings suggest that these mechanisms may indeed operate at least partly through differences in marriage timing; in particular, it appears that marriage is important in accounting for the association between the percentage of men in a field and fertility.

As noted, all models include a random effect at the field-of-study level to allow for unobserved heterogeneity within fields of study, and standard deviations of this term are presented at the bottom of Table 2. With no field-of-study-level controls, the standard deviation of the random intercept at the field level is 0.14. Once we add our key field-level controls in Model 2, the standard deviation falls to 0.078, indicating that field-level characteristics account for about one half of the variation across fields of study. Finally, once we include the proportion of women married by age 26, the standard deviation falls to 0.023, indicating that our field-level controls account for the vast majority of the variation in the timing of first births across fields of study. By comparison, in a model controlling for age, education, and a country-level intercept, but no field characteristics, Van Bavel (2010) reported a field-level standard deviation of 0.22, which changed little with additional field-level controls. The contrast provides some evidence of stronger field-level differences in Europe than in the U.S., but the difference may be explained by Van Bavel’s broader sample of women across education levels and countries.

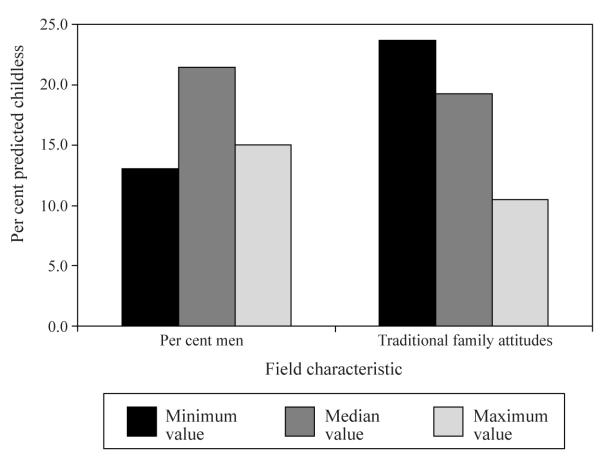

Simulations

To illustrate our findings in more intuitive terms, we ran simulations of childlessness based on Model 2 (Table 2) results, before marriage was included as an intervening variable. For each of our significant field-level variables, we predicted levels of childlessness at age 44, varying field-level characteristics at their minimum, median, and maximum values, and holding all other covariates at their mean values. Figure 3 illustrates the results of this exercise. Modelling the percentage of men as a quadratic captures the non-linear relationship between the percentage of men in a field and the timing of the first birth. There is a larger proportion of childless women in fields with the median percentage of men than in fields of study with either the minimum (health: 21 per cent men) or the maximum (engineering: 86 per cent men). The difference in childlessness between fields at the minimum and maximum values of percentage men is only 2 percentage points, while the difference between fields at the minimum and the median values is nearly 9 percentage points. There is a larger difference in proportion childless by family-role attitudes: a difference of 13 percentage points between those fields of study with the least and those with the most traditional attitudes about family roles.

Figure 3.

Predicted probability of childlessness at age 44 for women, derived from Model 2, varying key field-level characteristics, U.S. graduate women born 1960–79

Note: Estimates generated from Model 2 in Table 2. Field-level characteristics in turn set to their minimum, median, and maximum values while all other covariates held at their mean values. The minimum value for the traditional family attitudes variable reflects women with non-traditional attitudes towards family roles, so they exhibit higher levels of childlessness. This corresponds with our findings from Model 2 that suggest that higher values of the traditional family attitudes variables correspond to lower rates of childlessness.

Source: 2001, 2004, and 2008 Survey of Income and Program Participation, sample of women graduates with no children at timely degree completion.

Discussion

We set out to examine variation in the timing and occurrence of first births among U.S. college graduates by undergraduate field of study and, further, to explore mechanisms by which field of study might influence fertility. To our knowledge, this was the first study to provide an analysis of childbearing patterns by field of study in the U.S.

In initial analyses, we found significant differences in the timing and occurrence of first births across fields of study. Women who studied education and health were the earliest to have a first birth, while women in science and technology appeared to follow a pattern of delay and catch-up. The smallest proportion childless at age 44 were women in education and health, for whom the proportion was 10 percentage points smaller than for graduates in arts and humanities and general studies. The proportions childless for women in science and technology, social studies, and administration took intermediate values. These patterns are consistent with those reported in Europe (Lappegård 2002; Hoem et al. 2006b; Neyer and Hoem 2008), though we were surprised by the relatively large probabilities of first birth for women in science and technology, a field of study dominated by men, where the sex imbalance receives considerable attention and sparks much debate in the United States (e.g. Ceci and Williams 2007).

We estimated multilevel event-history models to assess the importance of field-of-study characteristics in accounting for individual-level variation in becoming a mother. We postulated that fields of study leading to jobs with smaller motherhood penalties–measured by differences in employment between women with young children and all other women–should impose fewer constraints on childbearing. These smaller penalties may reflect workplace accommodations that make it easier to combine work and family, and overall, penalties may signal to childless women information about the career costs of childbearing. We found little support for these possibilities, at least as modelled, with no significant association between motherhood employment penalties and first-birth timing.

We used the percentage of men within fields of study and traditional family-role attitudes typical of some fields as proxies for individual characteristics like nurturant attitudes, preferences for working with people, and a pro-family orientation that potentially select women both into the ‘caring’ fields and earlier motherhood. Our measure of family-role attitudes (derived from the NLSY79) was assessed early in the life course (at ages 14-21), largely before it was possible for experiences in fields of study to influence attitudes, thus providing a reasonably straightforward selection criterion. Because this measure was generated from a data source different from our main sample, it was probably measured with more error, which would have tended to attenuate estimated effects. We nevertheless found that traditional family-role attitudes were strongly associated with earlier age of first birth, with simulations showing a 13 percentage point difference in the proportions childless between the least traditional and the most traditional fields of study, ceteris paribus. Differences remained statistically significant after including controls for marriage patterns by field of study.

The percentage of men within a field of study was also significantly associated with first-birth timing, although both the pattern and interpretation of the association were somewhat more complicated. We found a curvilinear relationship: childlessness was greater in fields with intermediate percentages of men than in fields with either a small or a large percentage. The curvilinear pattern is consistent with larger probabilities of first birth among women in science and technology, a field heavily dominated by men (over 70 per cent), than among women in such fields as arts and social sciences in which the percentages of men are intermediate (about 40 per cent). Van Bavel (2010) reported a negative relationship between proportion of men and age at first birth across Europe, but no account was taken of potential nonlinearities. Exceptions to the general rule of higher fertility in more women-dominated fields have been discussed elsewhere (e.g., Hoem 2006b). We noted earlier the possibility that a large proportion of men may reflect selection processes, but may also mean greater partner availability and a marriage market that clears more quickly for women. For example, the presence of a large number of men with similar interests may result in women in science and technology marrying earlier than women in fields with smaller numbers of male graduates. Approximately 40 per cent of women in science and technology were married by age 26–larger than the proportions in arts and humanities, general studies, or social sciences. The proportion of men in a field of study could also reflect differences, not taken into account by other controls, in the association between field and subsequent career. For example, a positive association between field of study and predictable, stable career paths might explain the relatively small proportion childless among women in science and technology (despite its small proportion of women) (Hoem 2006b; Goldin and Katz 2008b).

Our results suggest that marriage timing plays an important role in mediating the link between field of study and fertility, with early marriage associated with earlier first births. Early marriage appears to account fully for the relationship between the percentage of men in a field of study and fertility: controlling for the proportion married by age 26 in Model 3 made the coefficient on the percentage of men statistically insignificant and the coefficient on family-role attitudes for fields of study fell in magnitude, although it remained statistically significant. Of course, given the very low rate of non-marital fertility among U.S. college graduates, it is not surprising that field-of-study characteristics operate substantially through marriage timing.

The United States ranks low relative to Europe in work-family support policies, such as paid leave and subsidized child care, but high in terms of flexibility of educational systems and labour markets (e.g., Gornick and Meyers 2003; Mandel and Semyonov 2006, 2009; Goldin and Katz 2008a). But despite these differences, our findings are largely in line with European studies (e.g. Hoem et al. 2006a, 2006b, Neyer and Hoem 2008, Van Bavel 2010). That is, the pattern of childlessness across fields of study is similar, although the differences between the fields of study appear to be smaller in the U.S. For example, in the U.S., the smallest estimated proportions childless were among women in education and health (16.4 and 18.5 per cent, respectively) and the largest were for women in the arts (25.2 per cent) and general studies (26.4 per cent), resulting in a difference across fields of study of 10 percentage points. By contrast, the analogous comparison in Sweden is approximately 10 per cent childless in education and health and 30 per cent in the arts and humanities, giving a difference of 20 percentage points (Hoem et al 2008b).

We have relied on informative data with relatively large samples to provide the best evidence to date on U.S. fertility differences across fields of study and on plausible explanatory mechanisms. Nevertheless, there are limitations in the data and the approach. We found some support for institutional and selection mechanisms, but causal pathways were difficult to identify. The SIPP contains limited individual-level variables relevant to fertility decisions, and unobserved factors may have confounded our estimated associations. The field-of-study measures we derived were merely proxies for factors that might explain how field of study influences fertility. For example, we used motherhood employment penalties to assess institutional features of the occupations characteristic of each particular field of study, but a more detailed examination would need to include more direct indicators, such as parental leave policy, job flexibility, and other aspects of working conditions (not measured by the SIPP). Further, field-of-study characteristics are themselves largely proxies for future career paths. It is likely that fields of study differ in the heterogeneity of occupations chosen after graduation.

Relatively little research has been devoted to the increasingly distinctive fertility of U.S. college graduates. Our findings lend support to the notion that women’s choice of field of study is based on factors that simultaneously predict earlier motherhood, namely, traditional family values. Our findings also highlight the importance of marriage timing in accounting for differences in fertility across fields of study. This analysis serves as a starting point for a better understanding of the relationship between the institutional factors that potentially constrain or facilitate family formation and the selection factors that shape women’s outlooks on work and family.

Appendix. Detailed fields of study, grouped by broad field

| Specific Field | Broad Field |

|---|---|

| Art/Architecture | Arts and humanities |

| Literature | Arts and humanities |

| Foreign language | Arts and humanities |

| Liberal arts | Arts and humanities |

| Theology | Arts and humanities |

| Education | Education |

| General studies | General studies |

| Health sciences | Health sciences |

| Business | Private and public administration |

| Communications | Private and public administration |

| Agriculture | Science and technology |

| Computers and information technology |

Science and technology |

| Engineering | Science and technology |

| Mathematics | Science and technology |

| Natural and biological sciences |

Science and technology |

| Psychology | Social sciences |

| Social sciences | Social sciences |

Fields in the first column indicate the 17 specific fields of study included in the survey questionnaire and used in our models. The second column shows into which broad field each specific field was assigned for the purpose of revealing broader patterns.

Source: 2001, 2004, and 2008 rounds of Survey of Income and Program Participation

References

- Becker Gary. A Treatise on the Family. Harvard University Press; Boston: 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Bianchi Suzanne. Maternal employment and time with children: Dramatic change or surprising continuity? Demography. 2000;37(4):401–414. doi: 10.1353/dem.2000.0001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Billari Francesco, Kohler Hans-Peter. Patterns of low and lowest-low fertility in Europe. Population Studies. 2004;58(2):161–176. doi: 10.1080/0032472042000213695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brewster Karen L., Rindfuss Ronald R. Fertility and women’s employment in industrialized countries. Annual Review of Sociology. 2000;26:271–296. [Google Scholar]

- Bhrolcháin Máire Ní, Beaujouan Éva. Fertility postponement is largely due to rising educational enrolment. Population Studies. 2012;66(3):311–327. doi: 10.1080/00324728.2012.697569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buchmann C, DiPrete TA. The growing female advantage in college completion: The role of family background and academic achievement. American Sociological Review. 2006;71(4):515–541. [Google Scholar]

- Carlson Marcia, McLanahan Sarah, England Paula. Union formation in fragile families. Demography. 2004;41(2):237–261. doi: 10.1353/dem.2004.0012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ceci Stephen J., Williams Wendy M. Striving for perspective in the Debate on Women in Science. In: Ceci SJ, Williams WM, editors. Why aren’t more Women in Science: Top Researchers Debate the Evidence. Vol. 254. American Psychological Association; Washington, DC, US: 2007. pp. 3–24. xx. [Google Scholar]

- Ceci Stephen J., Williams Wendy M., Barnett Susan M. Women’s underrepresentation in science: Sociocultural and biological considerations. Psychological Bulletin. 2009;135(2):218–261. doi: 10.1037/a0014412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diprete Thomas A., Morgan S. Philip, Engelhardt Henriette, Pacalova Hana. Do cross-national differences in the costs of children generate cross-national differences in fertility rates? Population Research and Policy Review. 2003;22(5-6):439–477. [Google Scholar]

- Edin Kathryn, Kefalas Maria. Promises I Can Keep: Why Poor Women Put Motherhood Before Marriage. University of California Press; Berkeley: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Ellwood David, Jencks Christopher. Kennedy School of Government Working Paper No. RWP04–008. Harvard University; 2004. The spread of single-parent families in the United States since 1960. [Google Scholar]

- England Paula. Comparable Worth: Theories and Evidence. Aldine de Gruyter; Hawthorne, NY: 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Fan Pi-Ling, Marini Margaret. Influences on gender-role attitudes during the transition to adulthood. Social Science Research. 2000;29(2):258–283. [Google Scholar]

- Folbre Nancy. [Viewed on 9/17/2010];Why girly jobs don’t pay, Economix. New York Times. 2010 Aug 16; 2010. http://economix.blogs.nytimes.com/2010/08/16/why-girly-jobs-dont-pay. [Google Scholar]

- Fortin Nicole M. The gender wage gap in the United States: The importance of money vs. people. Journal of Human Resources. 2008;43(4):884–918. [Google Scholar]

- Furstenberg Frank E., Jr Teenage childbearing as a public issue and private concern. Annual Review of Sociology. 2003;29(1):23–39. [Google Scholar]

- Glass Jennifer, Camarigg Valerie. Gender, parenthood, and job-family compatibility. American Journal of Sociology. 1992;98(1):131–151. [Google Scholar]

- Goldin Claudia. The long road to the fast track: Career and family. The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science. 2004;596(1):20–35. [Google Scholar]

- Goldin Claudia. The quiet revolution that transformed women’s employment, education, and family. American Economics Association Papers and Proceedings. 2006;96(2):1–21. [Google Scholar]

- Goldin Claudia, Katz Lawrence F., Kuziemko Ilyana. The homecoming of American college women: The reversal of the gender gap in college. Journal of Economic Perspectives. 2006;20(4):133–156. [Google Scholar]

- Goldin Claudia, Katz Lawrence F. The Race Between Education and Technology. Harvard University Press; Cambridge, Massachusetts: 2008a. pp. 247–284. [Google Scholar]

- Goldin Claudia, Katz Lawrence F. Transitions: Career and family life cycles of the educational elite. American Economic Review: Papers and Proceedings. 2008b;98(2):363–369. [Google Scholar]

- Gornick Janet C., Meyers Marcia K., Ross Katherin E. Supporting the employment of mothers: Policy variation across fourteen welfare states. European Social Policy. 1997;7(1):45–70. [Google Scholar]

- Gornick Janet C., Meyers Marcia K. Families that Work: Policies for Reconciling Parenthood and Employment. Russell Sage Foundation; New York: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Hakim Catherine. Work-Lifestyle Choices in the 21st Century: Preference theory. Oxford University Press; Oxford: 2000. Heterogeneous Preferences; pp. 157–193. [Google Scholar]

- Hoem Jan M., Neyer Gerda, Andersson Gunnar. Education and childlessness: The relationship between educational field, educational level, and childlessness among Swedish women born in 1955–59. Demographic Research. 2006a;14(15):331–380. [Google Scholar]

- Hoem Jan M., Neyer Gerda, Andersson Gunnar. Educational attainment and ultimate fertility among Swedish women born in 1955–59. Demographic Research. 2006b;14(16):381–404. [Google Scholar]

- Joshi Heather. Production, reproduction, and education: Women, children, and work in a British perspective. Population and Development Review. 2002;28(3):445–474. [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy Sheela, Bumpass Larry. Cohabitation and trends in the structure and stability of children’s family lives. Paper Presented at the Annual Meeting of the Population Association of America; Washington, DC. 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Lappegård Trude. Statistics Norway. Department of Social Statistics; [Viewed 9/17/2010]. 2002. Educational attainment and fertility patterns among Norwegian women. http://www.ssb.no/emner/02/02/10/doc_200218/doc_200218.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Lappegård Trude, Rønsen Marit. The multifaceted impact of education on entry into motherhood. European Journal of Population. 2005;21(1):31–49. [Google Scholar]

- Mandel Hadas. Winners and losers: The consequences of welfare state policies for gender wage inequality. European Sociological Review. 2010;28(2):241–262. [Google Scholar]

- Mandel Hadas, Semyonov Moshe. A welfare state paradox: State intervention and women’s employment opportunities in 22 countries. American Journal of Sociology. 2006;111(6):1910–1949. [Google Scholar]

- Mandel Hadas, Shalev Michael. How welfare states shape the gender pay gap: A theoretical and comparative analysis. Social Forces. 2009a;87(4):1873–1911. [Google Scholar]

- Mandel Hadas, Shalev Michael. Gender, class and varieties of capitalism. Social Politics. 2009b;16(2):161–181. [Google Scholar]

- Martin Steven P. Delayed marriage and childbearing: Implications and measurement of diverging trends in family timing. In: Neckerman Kathryn., editor. Social Inequality. Russell Sage; New York: 2004. pp. 79–119. [Google Scholar]

- Martín-García Teresa, Baízan Pau. The impact of the type of education and of educational enrollment on first births. European Sociological Review. 2006;22(3):259–275. [Google Scholar]

- McLanahan Sara. Diverging destinies: How children are faring under the second demographic transition. Demography. 2004;41(4):607–627. doi: 10.1353/dem.2004.0033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Misra Joya, Budig Michelle, Boeckmann Irene. Work-family policies and the effects of children on women’s employment and earnings. Community, Work and Family. 2011;14(2):139–157. [Google Scholar]

- Morgan Kimberly J. The ‘production’ of child care: How labour markets shape social policy and vice versa. Social Politics. 2005;12(2):243–263. [Google Scholar]

- Morgan S. Philip. Is low fertility a twenty-first century demographic crisis? Demography. 2003;40(4):589–603. doi: 10.1353/dem.2003.0037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgan S. Philip, Taylor Miles G. Low fertility at the turn of the twenty-first century. Annual Review of Sociology. 2006;32(1):375–399. doi: 10.1146/annurev.soc.31.041304.122220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgan Stephen L., Gelbgiser Dafna, Weeden Kim A. Feeding the pipeline: Gender, occupational plans, and college major selection. Social Science Research. 2013;42(4):989–1005. doi: 10.1016/j.ssresearch.2013.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Musick Kelly, England Paula, Edgington Sarah, Kangas Nicole. Education differences in intended and unintended fertility. Social Forces. 2009;88(2):543–572. doi: 10.1353/sof.0.0278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neyer Gerda, Hoem Jan M. Education and permanent childlessness: Austria vs. Sweden. In: Surkyn J, van Bavel J, Deboosere P, editors. Demographic Challenges for the 21st Century. A Tribute to the Continuing Endeavours of Prof. Dr. Em. Ron Lesthaeghe in the Field of Demography. VUB Press; Brussels: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Oppenheimer Valerie Kincade, Kalmijn Matthijs, Lim Nelson. Men’s career development and marriage timing during a period of rising inequality. Demography. 1997;34(3):311–330. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pettit Becky, Hook Jennifer L. Gendered Tradeoffs: Family, Social Policy, and Economic Inequality in Twenty-One Countries. Russell Sage Foundation; New York: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Ribar David C. The socioeconomic consequences of young women’s childbearing: Reconciling disparate evidence. Journal of Population Economics. 1999;12(4):547–565. [Google Scholar]

- Rindfuss Ronald R., Morgan S. Philip, Offutt Kate. Education and the changing age pattern of American fertility: 1963–1989. Demography. 1996;33(3):277–290. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rindfuss Ronald R., Guzzo Karen Benjamin, Morgan S. Philip. The changing institutional context of low fertility. Population Research and Policy Review. 2003;22(5-6):411–438. [Google Scholar]

- Sassler Sharon, Glass Jennifer, Levitte Yael, Michelmore Katherine. The missing women in STEM: Accounting for gender differences in entrance into STEM occupations. Annual meeting of the Population Association of America Presentation; 2011. 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Teachman Jay. Modeling repeatable events using discrete-time data: Predicting marital dissolution. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2011;73(3):525–540. [Google Scholar]

- Thornton Arland, Alwin Duane F., Camburn Donald. Causes and consequences of sex role attitudes and attitude change. American Sociological Review. 1983;48(2):211–227. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- United States Bureau of Labor Statistics . National Longitudinal Survey of Youth 1979 User’s Guide. Washington D.C.: [Viewed on 6/12/2012]. 2008. http://www.nlsinfo.org/nlsy79/docs/79html/tableofcontents.html. [Google Scholar]

- United States Census Bureau . Survey of Income and Program Participation User’s Guide Chapter 2, Revisions. Washington D.C.: [viewed on 6/12/2012]. 2009. http://www.census.gov/sipp/usrguide/ch2_nov20.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- United States Census Bureau . Fertility of American Women: 2008. Washington D.C.: [viewed on 8/22/2013]. 2010. Table 2: Completed fertility for women 40 to 44 years old by selected characteristics: June 2008. http://www.census.gov/prod/2010pubs/p20-563.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Van Bavel Jan. Choice of study discipline and the postponement of motherhood in Europe: The impact of expected earnings, gender composition, and family attitudes. Demography. 2010;47(2):439–458. doi: 10.1353/dem.0.0108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waldfogel Jane. International policies toward parental leave and child care. Future of Children. 2001;11(1):99–111. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]