Abstract

A novel technique is introduced for patterning and controllably merging two cultures of adherent cells on a microelectrode array (MEA) by separation with a removable physical barrier. The device was first demonstrated by separating two cardiomyocyte populations, which upon merging synchronized electrical activity. Next, two applications of this co-culture device are presented that demonstrate its flexibility as well as outline different metrics to analyze co-cultures. In a differential assay, the device contained two distinct cell cultures of neonatal wild-type and β-adrenergic receptor (β-AR) knockout cardiomyocytes and simultaneously exposed them with the β-AR agonist isoproterenol. The beat rate and action potential amplitude from each cell type displayed different characteristic responses in both unmerged and merged states. This technique can be used to study the role of β-receptor signaling and how the corresponding cellular response can be modulated by neighboring cells. In the second application, action potential propagation between modeled host and graft cell cultures was shown through the analysis of conduction velocity across the MEA. A co-culture of murine cardiomyocytes (host) and murine skeletal myoblasts (graft) demonstrated functional integration at the boundary, as shown by the progression of synchronous electrical activity propagating from the host into the graft cell populations. However, conduction velocity significantly decreased as the depolarization waves reached the graft region due to a mismatch of inherent cell properties that influence conduction.

Keywords: co-culture, cardiac electrophysiology, microelectrode arrays

Introduction

Biological tissues rely on complex interactions between different cell types to function. Although many tools are available to study individual cellular properties, probing the interactions between multiple cell types remains challenging because of the difficulty in maintaining a proper microenvironment while examining parameters of interest. Still, many cellular interactions have been studied with various cell types cultured together in numerous experimental systems. Utilizing microfabrication and more recently, micropatterning, investigators have achieved defined co-cultures by patterning biologically reactive molecules on the culture surface before cell plating. This has allowed the creation of stripes,1 islands,2 and other patterns of tissue for the investigation of cell–cell interactions or geometrical dependencies. The limitation of these methods was that patterning was often irreversible for the duration of an experiment. These methods of co-culture also involved a modified surface that resulted in changes to the cell–substrate interaction which may alter cell motility and function.

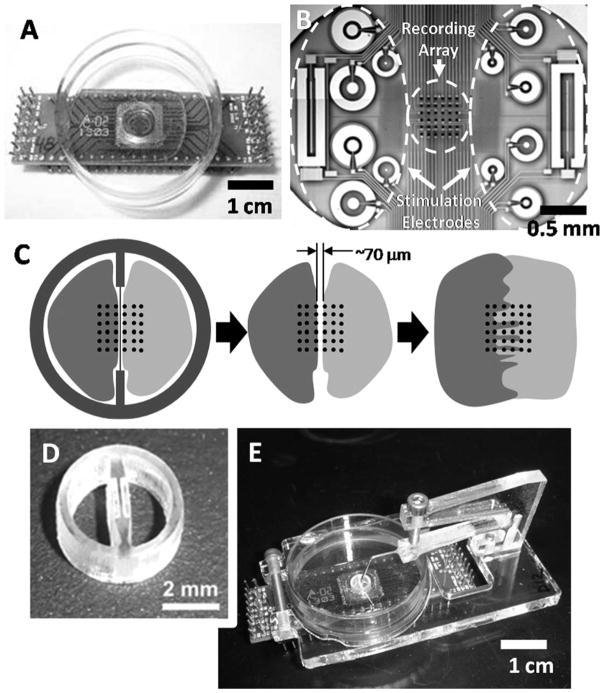

A new technique is presented for reversibly separating two populations of cells on the same surface to study electrical interactions (Figure 1). A divided surface was created using a laser-etched mold in the form of a small biocompatible ring bisected by a dividing wall. The dividing wall was only 50–100 μm thick in the culture area, achieving a narrow separation between the two cell culture chambers. The contact surface was planarized to allow isolation of two cell populations without the addition of a sealant or grease. Either of these substances may leave residue on the substrate and impede cell migration or worse impair cell function. Using acrylic as a material for this device, offered the additional advantage of being relatively low cost, yet durable enough to be reused following common sterilization techniques.

Figure 1. Co-culture apparatus.

(A) MEA designed for use with a standard 35-mm Petri dish and (B) the center well with the recording electrode array and larger auxiliary electrodes used for stimulation or additional recording electrodes over a larger area. (C) A co-culture wall divided the center recording array into 6 × 3 subarrays and allowed analysis of the boundary between cultures. (D) The reusable acrylic barrier bisects the ring and defines two chambers. (E) The ring is held face down in place with an accompanying support structure, consisting of a base clamped around the Petri dish, and an overhanging arm contacting the ring through a 20 gauge needle.

The co-culture ring defined small, isolated chambers that could be seeded with cells individually. After the cells have adhered to the surface, the co-culture ring could be removed without disturbing the specific pattern of cultures. This allowed the two cell populations to interact either indirectly, through diffusible factors, or directly by establishing cell–cell contacts over time to form a connected, heterogeneous culture.

Traditional in vitro methods such as voltage- or calcium-sensitive dyes and optical contraction assays can be applied in concert with the co-culture ring. However, combining this co-culture technique with microelectrode array (MEA) technology3 was done to provide real-time, noninvasive, and long term electrical monitoring of two distinct populations. With the barrier in place over a MEA, it was possible to culture two distinct cell populations on the same device, and following removal of the barrier, measure in real time differential responses to pharmacological stimulation. As a differential assay, neonatal cardiomyocytes from wild-type (WT) and β1,2-adrenergic receptor knockout (DKO) mice were co-cultured and stimulated with the β-AR agonist isoproterenol (ISO). Cardiomyocytes from DKO mice are not expected to respond to treatment with ISO, whereas cardiomyocytes from WT mice should show an increase in both action potential frequency and amplitude.4 Different characteristic responses were observed in DKO-WT cardiomyocyte co-cultures depending on whether they were in a separated or merged state, illustrating the relationship between role of β-AR signaling and cell coupling.

In the second application, integration between cardiomyocytes and skeletal myoblasts was demonstrated in a co-culture model for host–graft interactions. Skeletal myoblasts have been proposed as a possible candidate for cardiac cell therapy due to their autologous origin, exclusive differentiation into muscle-fiber cells, and high resistance to ischemia.5 Although transdifferentiation into cardiomyocytes does not take place,6 skeletal myoblasts have been shown to properly integrate,7 electromechanically couple,8 and even fuse9 with cardiac tissue. Specifically, C2C12 cells have been implanted into host myocardium in several animals studies,7,9 which made them an ideal candidate to demonstrate the co-culture device as a model for cell transplantation. Electrical monitoring during the merging process between cardiomyocytes and skeletal myoblasts in co-culture provided real-time analysis of propagation patterns between them, in particular highlighting the mismatch in conduction velocity between the two cell types. Illustrating this change in vitro may provide a useful understanding of a possible pro-arrhythmic potential associated with skeletal myoblasts.

Methods

Co-culture device

The co-culture device was designed with AutoCAD software (Autodesk, San Rafael, CA), and machined by etching and cutting a 2.8-mm thick cast acrylic sheet (Chemcast GP; Plastiglas de Mexico) with a CO2 laser ablation system (V-460 Laser Platform; Universal Laser Systems, Scottsdale, AZ).10 The device consisted of three parts: the ring (which is bisected by the barrier), the base, and the contact arm (Figure 1E). Following batch cutting, the rings were planarized with 1500-grit sandpaper, ultrasonically cleaned in 5% detergent, and rinsed in deionized water before use. The thickness of the wall separating cell cultures averaged 70 ± 30 μm, measured from micrographs acquired following planarization.

The contact arm was attached to the base of the device through screw holes on the underside of the arm. A 20-gauge needle bent at a 45° angle was attached to the end of the arm with epoxy and contacted the ring to apply pressure, maintain a seal, and prevent movement. The flexible arm and needle were lowered into the co-culture ring by applying pressure from the top using a finely threaded screw (0.5 mm pitch). Once the ring was in place, the needle from the overhanging arm was attached to the co-culture ring using a room temperature vulcanizing (RTV) sealant (Dow Corning, Midland, MI). To remove the ring, the top screw was removed, relieving pressure from the arm, and returning it to its original position while lifting the attached co-culture ring without lateral motion.

Cell culture

Ventricular cardiac myocytes were isolated from 1 to 2-day-old neonatal WT or DKO mice as described previously.4,11 Hearts were excised, atria were removed, and the remaining ventricles were minced and digested with collagenase type 2 (500 U/mL; Worthington Biochemical Corporation, Lakewood, NJ) in calcium and bicarbonate free Hanks solution with HEPES at 37°C with rocking. After 35 min, the tissue/enzyme solution was triturated to break up any remaining tissue and cells were filtered through a 40 μM cell strainer (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA). Cells were pre-plated to remove fibroblasts and resuspended in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s Medium (DMEM; Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA), 10% Nu Serum IV (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA), 5% certified fetal bovine serum (FBS; Hyclone, Logan, UT), 1 mM glutamine (Invitrogen), and 1× ITS media supplement (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO). Cardiomyocytes were plated onto laminin-coated (10 μg/μL; Invitrogen) dishes or MEAs at a density of 2 × 104 cells per chamber (10 μL). The cells are cultured at 37°C with 5% CO2. The barrier was removed after 4 days of culture, and the experiment was carried out the same day for studies requiring separated cultures. For studies examining merged cultures, experiments were performed one day later.

The integration model between host and graft tissue was developed using the murine atrial cardiomyocyte cell line HL-112 as the host, and C2C12 murine skeletal myoblasts as grafts. HL-1 cells were cultured in Claycomb media (Sigma-Aldrich) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Hyclone), 100 mM norepinephrine (Sigma-Aldrich), 100 U/mL penicillin-streptomycin (Invitrogen), and 4 mM L-glutamine (Invitrogen). C2C12 skeletal myoblasts were cultured in a solution containing 89% DMEM (Invitrogen), 10% FBS (Hyclone), and 1% penicillin–streptomycin (Invitrogen). HL-1 cardiomyocytes and C2C12 skeletal myoblasts were plated on the same day (Day 0) at equal densities of 3 × 104 cells per chamber. The barrier was removed the following day (Day 1).

Microelectrode array instrumentation

The MEAs each consisted of a 6 × 6 arrangement of platinum electrodes with 22 μm diameters spaced on 100 μm centers (Figure 1B), with additional larger electrodes on each side for electrical stimulation.13 Data was acquired from the MEA through 32 channels, with the four corner electrodes excluded. Petri dishes (35 mm diameter) with a 1 cm diameter through-hole were fixed to the package using biocompatible epoxy (EP42HT, Master Bond; Hackensack, NJ). Signals from the MEA were processed by a custom recording system that consisted of a 32-channel amplifier with a two-stage gain of 60 dB, 7 Hz first-order high-pass cutoff, and eighth-order low-pass cutoff at 3 kHz, as previously reported.14 Data from the amplifier board were digitized with 16-bit resolution at 10 ksps and acquired by a custom-designed visualization and extraction tool, written in Matlab™ (The MathWorks; Natick, MA).15

Analysis of merged WT-DKO co-cultures compared the average action potential amplitude and beat rate from individual electrodes during the first 30 sec (baseline) of the experiment with the average response in the last 30 sec (4.5–5 min). Conduction patterns in the host–graft model were analyzed by coordinating the local activation time (LAT), as defined as the point of maximum negative slope of an extracellular action potential, with its spatial location on the MEA. Active electrodes were then grouped together by three, and for each electrode triplet, the magnitude and direction of propagation were calculated as previously described by Bayly et al.16 The velocity of propagation in each culture was represented as a vector field, and presented in this work as the average of all triangulated vectors from the array.

Cellular co-cultures were kept at a temperature of 37°C, and compounds were added using a custom perfusion system with an integrated heater for the culture medium. The temperature of the perfused medium was measured on the MEA itself, using an integrated platinum temperature sensor and used for closed loop control to maintain the proper temperature.17

Statistics

All data is presented as the mean ± standard deviation. All comparisons were evaluated using a Student’s t-test calculated using Matlab™ (The MathWorks; Natick, MA), where significance was considered at P < 0.05.

Results

Homogenous co-culture

To validate the ability of the device to separate cultures and demonstrate integration, HL-1 cardiomyocytes were cultured on both sides of the co-culture divider (Figure 2A). Following the removal of the barrier, a defined separation was observed between cultures, and electrical activity included two asynchronous sets of action potentials (AP). Over the course of 24 h, HL-1 cardiomyocytes merged and formed a confluent culture with synchronous electrical activity (N = 5).

Figure 2.

(A) HL-1 cardiomyocytes were seeded on both sides of the barrier in a standard 35-mm Petri dish and allowed to merge. Initial cell contact was observed at 25 h. (B) The same experiment was performed on a MEA, where two asynchronous sets of electrical signal were initially observed, but synchronized after merging also 25 h after removing the barrier.

Heterogeneous co-culture

Two distinct populations of neonatal cardiomyocytes (WT and DKO) were co-cultured to measure differential responses to pharmacological stimulation (Figure 3). Separation of the cell populations was verified by microscopy and the presence of asynchronous action potentials from the two cell types on the MEA (Figure 3B). Shortly, after the barrier was removed and the two populations were still separated, the co-cultures were exposed to 10 μM ISO. The WT cells responded to ISO with an initial increase in beat rate and action potential amplitude, followed by a bursting rhythm of contractions (N = 7, Figure 4B). This response was consistently seen optically in WT cultures in the presence or absence of co-cultured DKO cells. The action potentials measured on the side of the MEA containing DKO cells were not modulated.

Figure 3.

(A) Following removal of the co-culture device, cells were divided over the surface of the MEA and exposed to 10 μM ISO. (B) A differential response between WT and DKO cultures was observed in action potential rate and amplitude as shown from two representative electrodes. WT activity displayed a bursting rhythm of contractions, whereas DKO cells did not respond due to a lack of appropriate receptors. The spaces in between WT data points indicate no activity. (C) Extracellular action potentials traces during the time indicated by the dashed boxes in (B) are shown during ISO exposure, revealing the dramatic impact of the bursting contraction behavior on the action potential amplitude.

Figure 4.

(A) The beat rate response of WT and DKO co-cultures in a heterogeneous population behaved as a single syncitium with synchronous rates of contraction across six representative electrodes. (B) WT cells responded with an increase in signal amplitude to 10 μM ISO, whereas DKO cells revealed a much smaller response that was likely due to the change of beat rate in both populations. (C) Analysis across electrodes within each region were consistent, and revealed a significant (*P < 0.05, represented as a bar between significant groups) increase in WT culture signal amplitudes due to ISO exposure. Repeated trials (N = 4) displayed similar significant increases in WT culture signal amplitudes without any bursting behavior as seen in Figure 3.

After removal of the barrier, the two cell populations began to migrate across the resultant space and form electromechanical connections. The co-culture behaved as a syncitium with a single synchronous beat rate that increased in response to ISO treatment. Addition of 10 μM ISO caused the AP amplitudes for WT cardiomyocytes to increase, whereas the AP amplitudes for DKO cardiomyocytes increased only marginally, as shown in Figure 4. In this particular example, the consistency between electrodes in heterogeneous cultures was demonstrated by analyzing individual electrodes from each side of the array, excluding two columns of electrodes where the two cell populations had merged (only three representative traces from each side are shown in Figure 4 for simplicity). Amplitudes on the WT electrodes increased 2.43 ± 0.26-fold over baseline (P < 0.05) and were significantly greater (P < 0.05) than the increase of 1.35 ± 0.19-fold over baseline from DKO electrodes (Figure 4C). Similar results were observed in repeated trials (N = 4) where on average WT cells increased in amplitude 2.40 ± 0.67-fold, whereas the DKO cells increased 1.14 ± 0.15-fold.

Host–graft interactions

A host–graft model was explored by co-culturing cardiomyocytes with skeletal myoblasts and studying the resulting conduction velocity on opposing sides of the MEA. HL-1 cardiomyocytes (host) were co-cultured with C2C12 skeletal myoblasts (graft) for one day before the barrier was removed. Within 24 h of removing the barrier, the two cell populations had physically merged on the MEA, as observed by microscopy. After the host and graft cell populations had merged, all channels displaying electrical activity were assumed to be originating from the host. This was validated by noting that the active electrodes were located on the appropriate side of the MEA. In longer term culture conditions (4 days), electrical activity was also observed on the side of the graft cells, but primarily in the vicinity of cells bordering the cardiomyocytes (N = 5; Figure 5A).

Figure 5. HL-1 cardiomyocytes (host) were co-cultured with C2C12 skeletal myoblasts (graft).

(A) A representation of the MEA displays electrodes after cultures have merged on Day 2. Electrodes displaying electrical activity on Day 2 were assumed to originate from the host, and are represented by solid circles. Additional electrodes on the graft side that previously did not display activity began exhibiting action potentials in subsequent days and are represented by triangles. (B) Activity from the highlighted electrodes are displayed for Day 4, showing a difference in amplitude between cultures, but still synchronous behavior (N = 5). (C) Conduction analysis on both sides on Day 4 indicated that electrical activity originated from the host, and experienced a significant (P < 0.05) decrease in conduction velocity on the graft side, as averaged across five beats.

The action potentials originating from the graft side of the MEA, while synchronous, had lower amplitudes than simultaneous host action potentials (Figure 5B). Analysis of conduction patterns within the sample shown in Figure 5C also demonstrated a significant decrease (P < 0.05) in the velocity of action potential propagation from 12.9 ± 2.7 mm/sec on the host side, to 2.0 ± 0.8 mm/sec on the graft side. Over all cultures (N = 5), conduction velocity through the graft decreased to only 37 ± 26% of the velocity through host tissue.

For all samples, conduction analysis indicated that action potentials originated from the host side and propagated into the graft side. This was confirmed by the addition of 10 μM ISO which should only stimulate cardiomyocytes8 because skeletal myoblasts lack the necessary β-ARs to appropriately respond. After ISO addition, all samples (N = 5) remained synchronous and beat rates increased within a range of 12–130%. The amplitudes of the APs on the host side increased as expected within a range from 3% to 30%, whereas the amplitudes of the graft APs did not change more than 3%.

Discussion

A method was demonstrated for the reversible separation of two cell populations on an MEA through a physical barrier, which upon removal allowed cell growth and migration. Planar MEAs were well matched with the co-culture barrier technique because of the ability to record electrical activity in multiple regions of the culture simultaneously and noninvasively. The capabilities of this device were demonstrated using murine HL-1 cardiomyocyte cultures, murine neonatal cardiomyocytes with different genetic compositions (WT and β1,2-AR DKO), and finally murine C2C12 skeletal myoblasts with HL-1 cardiomyocytes.

In vivo, β-ARs initiate cellular responses to sympathetic stimulation that lead to increases in the rate and strength of contraction. The effect of adrenergic stimulation on cardiomyocytes was initially examined in the co-culture device by plating cells from WT and DKO mice followed by treatment with β-AR specific agonist ISO (Figure 3). When separated from DKO cardiomyocytes, WT cardiomyocytes initially responded to β-AR agonist treatment by an increased rate and action potential amplitude in a bursting pattern, whereas the DKO cardiomyocytes exhibited no response. Within days of barrier removal, a heterogeneous monolayer of cells formed and acted as a single electrical syncitium. However, the monolayer maintained the characteristic response to pharmacologic stimulation of its constituent populations (Figures 3 and 4). Interestingly, after the cell populations integrated, WT culture action potentials did not exhibit the same bursting patterns in response to ISO seen in isolated cultures. Further explanation of this phenomenon requires further study and is currently being investigated. Nonetheless, this data demonstrated the ability of the device to perform a differential assay that began to examine how molecular signaling can be modulated through cellular interactions.

This experimental platform was also applied to study host–graft interactions by measurement of the conduction velocity. Murine HL-1 cardiomyocytes (host) and murine C2C12 skeletal myoblasts (graft) were used as a model of cardiac cell therapy. The use of MEA technology allowed the examination of the electrical interface between host and graft cells, and the limited ability of graft cells to conduct an electrical signal beyond that boundary. In this case, only the graft cells at the host boundary displayed action potentials, which typically did not extend past one or two electrode spacing lengths (100–200 μm). It has been shown that the early stage C2C12 skeletal myoblasts used in this study develop proteins for electrical connections (connexin43) and mechanical coupling (N-cadherin) within days of plating, but downregulate them as they differentiate unless they are coupled with cardiomyocytes.8 This likely explains why electrical activity was found only in graft cells close to the boundary and not further into the graft region.

The boundary between cell types over the MEA was made clear by the differences in conduction velocity. Conduction is influenced by a number of factors, including cell size, orientation, gap junction density, or ion channel configuration.18 Changes in propagation characteristics could lead to an abnormal rhythm with unknown results in vivo. Studies have already shown evidence that cell transplantation may lead to pro-arrhythmic consequences in vitro,19,20 and in vivo when autologous myoblasts were transplanted in humans.21 The observed slowing of conduction velocity from skeletal myoblast populations demonstrated the unique ability of this model to examine electrical connectivity at, and propagation through, heterogeneous tissue boundaries.

The simplicity of the device lends itself to modifications to fit other experimental platforms, culture dishes, or microscope stages, and it is further supported by its low-fabrication costs and its ability to be reused. Because the barrier technique does not require surface coating of either the ring or the substrate, the separation of cells is reversible and not limited to specific cell types. It is also of interest to use this technique toward studying the electrical characteristics of neuron innervations of cardiac tissue, and modulating these interactions through pharmacological or electrical stimulation. Without significant additional preparation or modification, the physical barrier may be capable of preventing axonal migration outside the co-culture chamber, and therefore, separating the cells in a specific and effective manner.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr. Joseph C. Wu for his generous donation of the C2C12 skeletal myoblast cell line. This work was supported in part by the California Institute for Regenerative Medicine through cooperative agreement RS1-00232-1 (GTAK), by the National Institutes of Health grant R01HL071078 (BKK), and by the National Science Foundation Graduate Student Research Fellowship (MQC).

Contributor Information

Michael Q. Chen, Dept. of Bioengineering, Stanford University, Stanford, CA 94305

R. Hollis Whittington, Dept. of Electrical Engineering, Stanford University, Stanford, CA 94305.

Peter W. Day, Dept. of Molecular and Cellular Physiology, Stanford University, Stanford, CA 94305

Brian K. Kobilka, Dept. of Molecular and Cellular Physiology, Stanford University, Stanford, CA 94305

Laurent Giovangrandi, Dept. of Electrical Engineering, Stanford University, Stanford, CA 94305.

Gregory T. A. Kovacs, Dept. of Electrical Engineering, Stanford University, Stanford, CA 94305. Dept. of Medicine, Stanford University, Stanford, CA 94305

Literature Cited

- 1.Rohr S, Scholly D, Kleber A. Patterned growth of neonatal rat heart cells in culture. Morphological and electrophysiological characterization. Circ Res. 1991;68:114–130. doi: 10.1161/01.res.68.1.114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bian W, Tung L. Structure-related initiation of reentry by rapid pacing in monolayers of cardiac cells. Circ Res. 2006;98:e29–e38. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000209770.72203.01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Whittington RH, Giovangrandi L, Kovacs GTA. A closed-loop electrical stimulation system for cardiac cell cultures. IEEE Trans Biomed Eng. 2005;52:1261–1270. doi: 10.1109/TBME.2005.847539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Devic E, Xiang Y, Gould D, Kobilka B. Beta-adrenergic receptor subtype-specific signaling in cardiac myocytes from beta 1 and beta 2 adrenoceptor knockout mice. Mol Pharmacol. 2001;60:577–583. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Menasché P, Hagège AA, Scorsin M, Pouzet B, Desnos M, Duboc D, Schwartz K, Vilquin J-T, Marolleau J-P. Myoblast transplation for heart failure. Lancet. 2001;357:279–280. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)03617-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Reinecke H, Poppa V, Murry CE. Skeletal muscle stem cells do not transdifferentiate into cardiomyocytes after cardiac grafting. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2002;34:241–249. doi: 10.1006/jmcc.2001.1507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Koh GY, Klug MG, Soonpaa MH, Field LJ. Differentiation and long-term survival of C2C12 myoblast grafts in heart. J Clin Invest. 1993;92:1548–1554. doi: 10.1172/JCI116734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Reinecke H, MacDonald GH, Hauschka SD, Murry CE. Electromechanical coupling between skeletal and cardiac muscle: implications for infarct repair. J Cell Biol. 2000;149:731–740. doi: 10.1083/jcb.149.3.731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Reinecke H, Minami E, Poppa V, Murry CE. Evidence for fusion between cardiac and skeletal muscle cells. Circ Res. 2004;94:e56–e60. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000125294.04612.81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chen MQ, Yu J, Whittington RH, Wu JC, Kovacs GTA, Giovangrandi L. Modeling conduction in host-graft interactions between stem cell grafts and cardiomyocytes. IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Conference; Minneapolis: IEEE; 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Devic E, Xiang Y, Gould D, Kobilka B. Beta-adrenergic receptor subtype-specific signaling in cardiac myocytes from beta(1) and beta(2) adrenoceptor knockout mice. Mol Pharmacol. 2001;60:577–583. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Claycomb WC, Nicholas A, Lanson J, Stallworth BS, Egeland DB, Delcarpio JB, Bahinski A, Nickolas J, Izzo J. HL-1 cells: a cardiac muscle cell line that contracts and retains phenotype characteristics of the adult cardiomyocyte. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:2979–2984. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.6.2979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chen MQ, Xie X, Wilson KD, Sun N, Wu JC, Giovangrandi L, Kovacs GTA. Current-controlled electrical point-source stimulation of embryonic stem cells. Cell Mol Bioeng. 2009;2:625–635. doi: 10.1007/s12195-009-0096-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gilchrist KH, Barker VN, Fletcher LE, DeBusschere BD, Ghanouni P, Giovangrandi L, Kovacs GTA. General purpose, field portable cell-based biosensor platform. Biosens Bioelectron. 2001;16:557–564. doi: 10.1016/s0956-5663(01)00169-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Whittington RH, Chen MQ, Giovangrandi L, Kovacs GTA. Temporal resolution of stimulation threshold: a tool for electrophysiologic analysis. IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Conference; New York City: IEEE; 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bayly PV, KenKnight BH, Rogers JM, Hillsley RE, Ideker RE, Smith WM. Estimation of conduction velocity vector fields from epicardial mapping data. IEEE Trans Biomed Eng. 1998;45:563–571. doi: 10.1109/10.668746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Whittington RH, Kovacs GTA. A discrete-time control algorithm applied to closed-loop pacing of HL-1 cardiomyocytes. IEEE Trans Biomed Eng. 2008;55:21–30. doi: 10.1109/TBME.2007.910641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kleber AG, Rudy Y. Basic mechanisms of cardiac impulse propagation and associated arrhythmias. Physiol Rev. 2004;84:431–488. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00025.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chang MG, Tung L, Sekar RB, Chang CY, Cysyk J, Dong P, Marban E, Abraham R. Proarrhythmic potential of mesenchymal stem cell transplantation revealed in an in vitro coculture model. Circulation. 2006;113:1832–1842. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.593038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Roy S, Chen MQ, Kovacs GTA, Giovangrandi L. Conduction analysis in mixed cardiomyocytes-fibroblasts cultures using microelectrode arrays. IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Conference; Minneapolis: IEEE; 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Menasche P, Hagege AA, Vilquin J-T, Desnos M, Abergel E, Pouzet B, Bel A, Sarateanu S, Scorsin M, Schwartz K, Bruneval P, Benbunan M, Marolleau J-P, Duboc D. Autologous skeletal myoblast transplantation for severe postinfarction left ventricular dysfunction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2003;41:1078–1083. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(03)00092-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]