Abstract

We sought to ascertain the rates and mechanisms of uptake of markers for regional myocardial blood flows.

Methods

The rates of exchange of potassium and thallium across capillary walls and cell membranes in isolated blood-perfused dog hearts were estimated from multiple indicator dilution curves recorded for131I-albumin, 42K and 201Tl from the coronary sinus outflow following injection into arterial inflow. Analysis involved fitting the observed dilution curves with a model composed of a capillary-interstitial fluid-cell exchange region and nonexchanging larger vessels.

Results

Capillary permeability surface products (PSc) for potassium and thallium were similar, 0.82 ± 0.33 (mean ± s.d., n = 19) and 0.87 ± 0.32 ml min−1 g−1 (n = 24) with a ratio for simultaneous pairs of 1.02 ± 0.27 (n = 19). For the myocardial cells, PSpc averaged 3.7 ± 3.1 ml min−1 g−1 (n = 19) for K+ and 9.5 ± 3.9 (n = 24) for Tl+; the ratio of potassium to thallium averaged 0.40 ± 0.19 (n = 18), thereby omitting a single high value for potassium. This high cellular influx for thallium is interpreted as due to its passage through ionic channels for both Na+ and K+.

Conclusion

The high permeabilities and large volumes of distribution make thallium and potassium among the best ionic deposition markers for regional flow. Their utility for this purpose is compromised by significant capillary barrier limitation retarding uptake; so regional flow is underestimated modestly in high-flow regions particularly.

Keywords: capillary permeability, cation transport, myocardial imaging agents, regional myocardial blood flow

The imaging of regional myocardial deposition of certain alkali metal ions, potassium, rubidium and thallium has become an important clinical tool in the assessment of myocardial ischemia. Interpretation of the images is based ordinarily on two premises:

The tracer is deposited in proportion to flow, supposedly being flow-limited in its transcapillary passage and not barrier-limited.

It is handled like potassium in the cell.

Neither of these premises has been fully examined. The transport of thallium and potassium from the bloodstream into the cells involves the traversal of the capillary endothelial barrier, the interstitial space and the cell membrane. The initial uptake into the cell is influenced by all of these events. Tancredi et al. (1) and Yipintsoi et al. (2) demonstrated that the transcapillary extraction of potassium is 40%–70%, diminishing with higher flows. Thus, if thallium and rubidium are potassium analogs, they would not be 100% extracted, and the deposition would not be directly proportional to the local regional flow, but would be less extracted in high flow regions. Second, the main determinant of a tracer retention in an organ being its intracellular retention, the kinetics of cellular permeation and intracellular volume of distribution play critical roles.

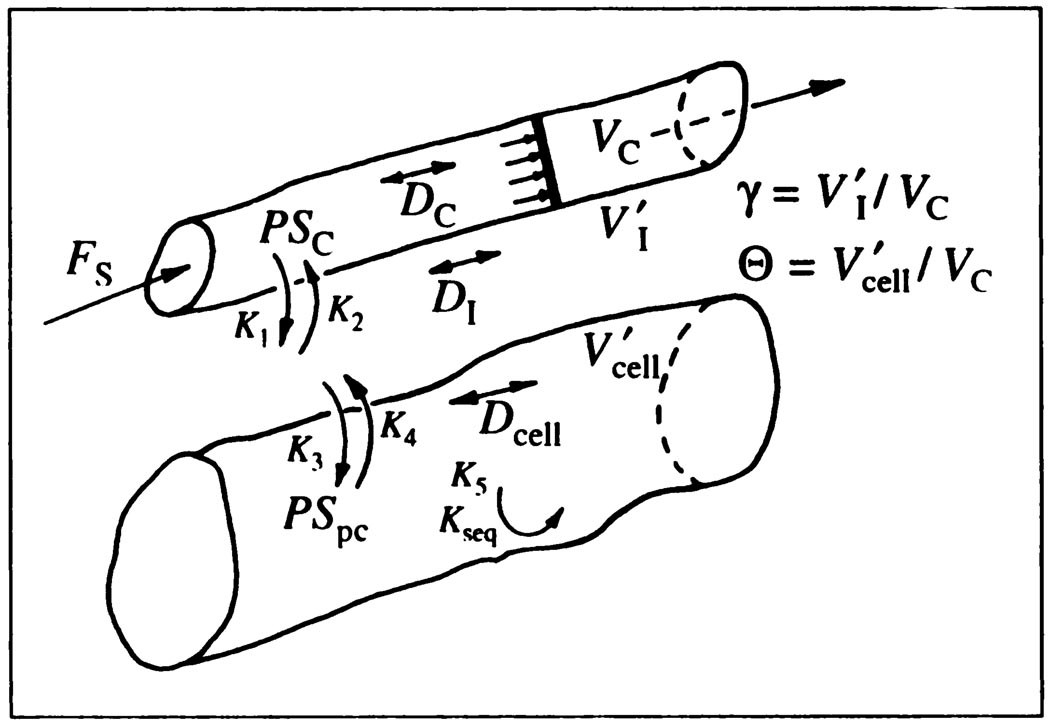

For the analyses to be undertaken, a capillary-ISF-cell model (3) similar to the RGB model of Rose, Goresky and Bach (4). RGB, was developed as an extension of the single capillary-ISF (interstial fluid model) model of Bassingthwaighte (5). Like the RGB model, it includes cellular uptake (Fig. 1). Axial diffusion acts to dissipate concentration gradients existent in the spatially distributed system, and while it is not of much importance in influencing estimates of permeabilities, it does influence the initial part of the outflow response. The model is presented and used as a differential operator. This enables its use with any input function, including experimental data, without using a convolution integration.

FIGURE 1.

Model for capillary-ISF-cell exchange in the myocardium. Flow is piston-flow. D’s are axial diffusion coefficients. PScap and PSpc are capillary and myocardial cell permeability-surface area products and the V’s are volumes of distribution in capillary, ISF, and myocardial, parenchymal cells. The K’s are the analogous rate constants, a PS divided by a volume, used by Rose et al. (4). Endothelial cell volumes, about 0.007 ml/g, are considered negligible and are not included in the model.

The purposes of this study were to estimate the transport rates of potassium and thallium from the blood into the myocardial cells, to relate these to possible mechanisms of transport and to relate the observed transport rates to the interpretation of spatial profiles of relative deposition densities, such as might be obtained in three-dimensional reconstructed images.

Values for capillary permeability-surface area products, PScap, in dog hearts had been obtained using incomplete models by Ziegler and Goresky (6) for rubidium and by Tancredi et al. (1) for potassium. The latter used the model of Renkin (7,8) and Crone (9) to calculate PScap from the initial extractions of K+ compared to albumin, and the results undoubtedly underestimated PScap for K+ to some extent. To estimate cell permeability-surface area products, PSpc, it is necessary to obtain estimates not only of PScap but also of interstitial and intracellular volumes of distribution. The interstitial volume of distribution, , varies little in blood-perfused isolated hearts in the study by Yipintsoi et al. (2), although it does expand in isolated Krebs-Henseleit perfused rabbit heart preparations. Further, estimates of K+ and Tl+ exchange across the membranes are almost insensitive to the value of . In contrast, the volume of distribution in the parenchymal cells, the myocytes. , is of great importance in governing the rate of washout after the first couple of minutes; values of are greater than those for cellular water space, about 0.55 ml g−1 in dog heart, because of either a concentrating process such as Na/K ATPase or intracellular binding, or both. (The residue function and washout technique of Zierler (10) and Tancredi et al. (1) is more sensitive to than is the outflow dilution technique.)

METHODS

The experiments were performed on isolated, Langendorff, nonworking, spontaneously beating canine hearts weighing 60–110 g and perfused with blood at 37.5°C taken from the femoral artery of anesthetized, heparinized, artificially ventilated, support dogs weighing about 30–35 kg. The hearts were perfused with oxygenated Ringer’s solution during the 30–45 sec required for transfer and were at no time without perfusion. The preparation is similar to that used by Tancredi et al. (1), so the data should be comparable. The perfusion rate was controlled with a roller pump on the inflow line. Perfusion pressure (70–120 mm Hg), perfusate temperature (controlled at 37 ± 0.5°C), coronary sinus pressure (0 ± 3 mm Hg), heart rate and heart weight (so that any weight changes over 2 g were avoided) were monitored and recorded continuously. Perfusion pressures were 80–95 mmHg. The azygos vein, venae cavae and pulmonary artery were ligated. Flow (F) from the coronary sinus, right atrium and right ventricle was via a short cannula (0.25 ml volume) passing from the right ventricle through its wall into a funnel from which the outflow drained into a rotating sampler system with sample collection periods of 0.4, 1, 2 or 4 sec. The drainage from the left ventricle, from the sum of aortic valve leakage and Thebesian vein drainage, was small and was collected via a small cannula through the thin part of the apical myocardium. Flows through the cannulae were measured, and venous samples were collected for hematocrit. At the end of each experiment, the wet weight (W) of the myocardium devoid of fatty tissue was measured. Plasma flow, FS = (1 − Hct) F/W.

The experiments were performed using the standard multiple indicator dilution method (11). After stabilizing perfusion pressure, flow, heart weight and blood temperature, samples of venous blood were removed for hematocrit and for background isotopic activities. Then, a mixture of 131I-albumin (half-life 8.1 days; 20 µCi RISA), 42KCl (half-life 12.4 hr; 30–40 µCi) and 201Tl-CI (half-life 73.5 hr, 30 µCi) dissolved in saline was injected as a bolus (total volume 0.4–0.8 ml) into the cannulated aortic inflow to the coronary arteries. The duration of the injection was approximately 0.5–1 sec. At this time, the multiple sampling device was started and coronary sinus venous blood was sampled at 1.0-sec intervals when the flow was low and at 0.4-sec intervals when the flow was high for the first 30 samples; the collection rate was set at 2- or 4-sec intervals for the second 30 samples. Data collection for the dilution curves covered from 72 sec to over 2 min. When sampling was completed, the flow was again measured. The collected blood samples were processed and weighed prior to counting in a well counter. For each curve, a measured aliquot of injectate was also counted with the blood samples and correction was made for isotopic decay occurring during the counting period.

By knowing the time of collection, t, the isotopic activity in each sample, C(t), the injected dose of each tracer, q0 and the measured plasma flow, FS, we calculated the normalized dilution curves, the pulse response for 131I labeled albumin, hR(t), and for the permeant diffusible tracers, hD(t), i.e. for 42K and 201Tl, hK(t), and hTl(t), using the general equation:

| Eq. 1 |

From hR(t) and hD(t) for each of the permeating tracers, an instantaneous fractional extraction, E(t), was calculated on the basis that the reference tracer albumin does not leave the capillary blood:

| Eq. 2 |

The usual value for E used for the calculation of PScap is the maximal plateau value Emax, which we chose as the best estimate of the average fractional extraction on the basis that it represented the extraction at approximately the mean of the regional flows to the tissues of the organ. The Renkin-Crone expression for estimating PScap is

| Eq. 3 |

The modification by Guller et al. (12), to use 1.14 Emax instead of Emax, is not appropriate here: it is to be used for tracers which are restricted to the extracellular space or enter cells slowly; the factor 1.14 served to compensate for back diffusion from interstitial space to capillary.

The diffusion coefficient at 25°C for potassium in 0.15 molar electrolyte solution is 1.84 × 10−5 cm2 s−1 (13). As illustrated by Ussing et al. (14), the effective hydrated radii of the alkali metal ions diminish with increasing atomic weight being Na 1.78, K 1.22, Rb 1.18 and Cs 1.16 Å. Thallium, with an atomic weight of 204, lacks waters of hydration because of its low charge density and has a diffusion coefficient rather close to that of potassium in spite of its larger atomic weight. The atomic radius of thallium is given as 1.99 Å, the ionic radius of Tl+ as 1.49 Å and of Tl3+ as 1.05 Å. In our studies the thallous form with 1.49 Å is the relevant one, and the activity coefficient is about 0.88 (15). The limiting equivalent conductivity of Tl+ in aqueous solution is about 74.7 ohm−1 cm−2 mol−1 compared to that for potassium of 73.5 [(13), appendix 6.1], from which we calculate a thallium diffusion coefficient of 1.87 × 10−5 cm2 s−1.

Study Model

The single capillary component of the model is basically an extension of the two-region model of Bassingthwaighte (5) for capillary-interstitial fluid exchange into a three-region model for capillary-ISF-cell exchanges thereby accounting for cellular uptake and loss, described in detail with respect to the numerical methods by Bassingthwaighte, Chan and Wang (3). With axial diffusion set to zero, this model reduces to that of Rose et al. (4). If in addition no return flux is allowed from the cell to the ISF, it reduces to that of Ziegler and Goresky (6). With the further restraint of no permeation into the cell, it reduces to that of Sangren and Sheppard (16) and Goresky et al. (17).

The equations for the three regions are parabolic partial differential equations, which are required to describe the concentration gradients with position along the length of the capillary. Regions are denoted by subscripts, cap for capillary, is for interstitial fluid, and pc for parenchymal cells in general. Radial diffusional relaxation times for intercapillary distances in the heart are short compared with the time constants for capillary exchange, so that interstitial and intracellular concentration gradients in a radial direction are taken to be negligible (5, 4, 18). See the Appendix for relevant calculations. As a result, the equations do not need to be represented in cylindrical coordinates. However, the effective axial diffusion coefficients, D, cm2 s−1, are retained. In the plasma, these represent “dispersion” coefficients due to a combination of velocity shearing, Taylor diffusion, axial molecular diffusion and mixing within plasmatic gaps between erythrocytes. The concentration inside the capillary Ccap(x, t) is given by the equation:

| Eq. 4 |

where Dcap is the effective diffusion coefficient in the axial direction in the blood, FS is the plasma or solute-containing fluid flow (FS = Fblood(1 − Hct)) ml min−1 g−1. Vcap is the effective volume of distribution for the solute in the capillary, ml g−1 of the tracer in the blood within the capillary, and is therefore usually the plasma space [in the heart about 0.07 ml g−1 × (1 − Hct)], or about 0.042 ml g−1 at Hct = 0.6. FSL/Vcap is the velocity, cm/s, in the capillary, where the implicit assumption is of a uniform velocity or plug flow. The value of Dcap can be varied to account for axial dispersion in the capillary, which may differ for permeating and nonpermeating solutes, and allow one to account for differences in axial dispersion or for Taylor diffusion effects. For the reference tracer, albumin, PScap was set to zero.

The equations for the interstitial, Cisf, and intracellular concentrations in a myocardial parenchymal cell, Cpc, lack flow terms:

| Eq. 5 |

and

| Eq. 6 |

where Gpc is a first-order consumption, ml min−1 g−1. The ratio is the first order rate constant, min−1, for intracellular sequestration or irreversible binding, and is equivalent to the kseq or k5 of Rose et al. (4). For this study, Gpc was taken to be zero for potassium and thallium, since these are not consumed and may reflux. The ratios , are obtained from the model analysis of the data. We used Vcap = 0.042 ml g−1 (19). is ordinarily much larger than the water space of about 0.55 ml g−1 since intracellular concentrations of K+ and Tl+ in the steady state are higher than in plasma.

The initial condition is that the tracer concentrations everywhere are zero at t = 0. The input function Ccap(t, x = 0) is the observed albumin dilution curve deconvoluted by the intravascular transport function. For a single capillary with zero axial dispersion (Dcap = 0) it is simply hR(t) shifted earlier by one capillary transit time, hR(t + Vcap/FS) (5,4,20). Since FS is measured and Vcap/FS is eliminated as a parameter of the solution by the integration along the length of the capillary, the only unknown parameters to be estimated are PScap, PSpc, γ, and Θ. The dispersion coefficients were fixed at fractions of the free diffusion coefficients, 0.9 in plasma and 0.25 in interstitial fluid and cells, following the observations of Safford and Bassingthwaighte (18) and Safford et al. (21). Although , could have been fixed at about 6.0, the range from 4 to 8 having little influence on the estimates of the other parameters, our data using 58CoEDTA (22), sucrose and L-glucose as extracellular markers (23) show substantial regional variations in and therefore variation in γ was allowed by leaving it as a free parameter.

The solutions to the equations were obtained numerically in the fashion described by Bassingthwaighte, Chan and Wang (3). The numerical method for the capillary-ISF-cell model gives accurate areas and mean transit times, fulfilling conservation conditions, even at high values of . The overall strategies for using the model to fit the data are those described by Kroll et al. (24). The parameter estimates for the best fit of the single capillary model to the data were obtained using manual parameter adjustment by analog-potentiometers to set the digital-valued parameters of the FORTRAN-based model under SIMCON (25). A particular virtue in using analog potentiometers for setting parameters rather than entering digital values at a keyboard is that the parameter value can remain unknown to the investigator until he looks it up in digital form after a final fit of model to data has been obtained. The coefficient of variation, CV, was used as a measure of the goodness of fit, extending over the full duration of the dilution curves (72–150 sec).

Multicapillary analysis was also used to account for the known heterogeneity of regional myocardial blood flows. The model consisted of 20 of the capillary-tissue units described above in a parallel arrangement assuming independence of the units from each other. The weighting and the flows used to represent the probability density function by 20 paths are as described by (26).

RESULTS

Twenty-four sets of indicator dilution curves were obtained in the hearts from six dogs. Four to seven tracer injections were made in each dog heart study, but failures of injection or sampling occurred in those not reported. In five instances, 42K was not available in adequate amounts and curves were not obtained.

Form of Indicator Dilution Curves

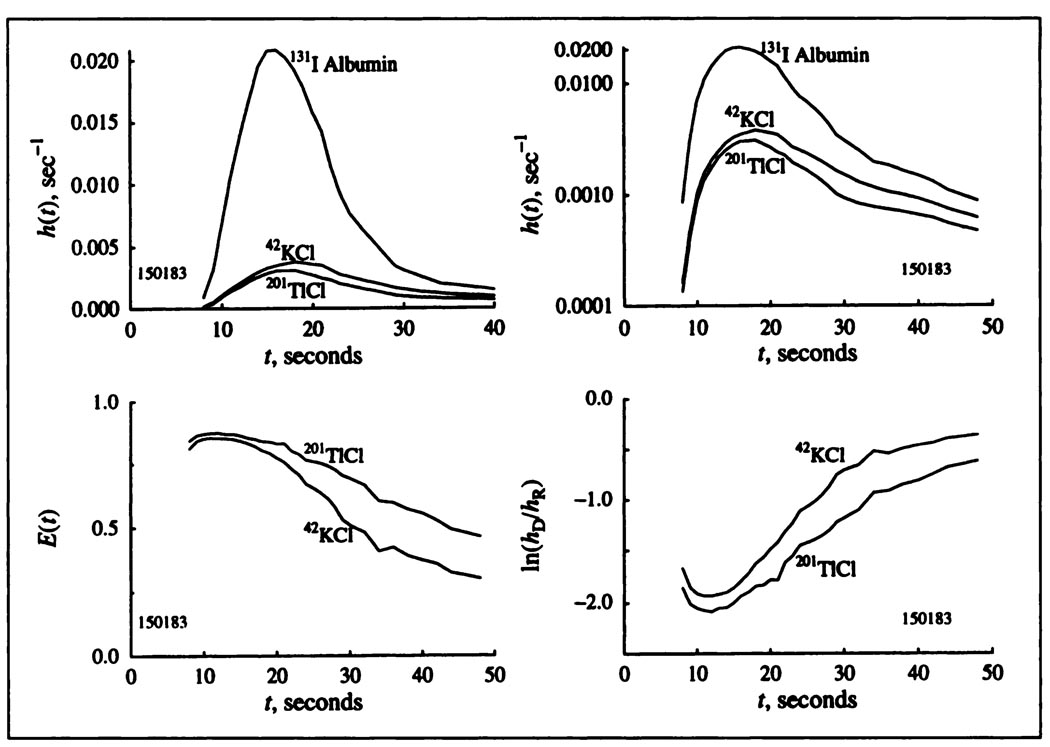

An example of recorded indicator dilution curves, h(t), is shown in Figure 2 (upper panels, linear and logarithmic scales). The first part of the dilution curves for both potassium and thallium has a shape similar to that for albumin but lower. For both there are long low tails continuing over the sampled times up to 72–200 sec, as for potassium (1), and for Tl+ (27). The residual fraction retained in the heart is about one-third of the entering dose by the end of the first minute and is slow to wash out, in accord with long retention by the muscle cells. There is a striking difference in the downslope portion following the peaks of the curves: the thallium h(t)’s are lower than the potassium curves, which means that thallium is better retained by the tissue than is potassium.

FIGURE 2.

Observed coronary sinus outflow dilution curves h(t), for potassium and thallium plotted with linear and logarithmic ordinate scaling FS = 0.67 ml min−1 g−1 Hct = 40%, perfusion pressure = 80 mmHg, heart rate = 64/min. Lower left panel: Instantaneous fractional extractions, E(t). Lower right panel: The ratios hD(t)/hR(t) plotted on a logarithmic scale.

Differences between potassium and thallium are accordingly found in the instantaneous net extraction E(t) after 15 sec (Fig. 2, left lower) and the ratios of the potassium and thallium concentration to the albumin concentration at each time point (Fig. 2, right lower). E(t) usually remains positive for about a minute at medium and low flows indicating that net extraction continues. E(t) for thallium remained positive longer than for potassium, always for the first minute. In general, not seen in Figure 2, during the first seconds the potassium E(t)’s tended to be almost flat during the upstroke and peak of h(t), but the thallium E(t)’s started a little lower and increased to a later flat peak that was usually slightly higher than for potassium. Initially flat E(t)’s suggest that there is little heterogeneity in regional myocardial blood flows, even justifying single-capillary modeling (28,29), which is the basis of our analysis. To check this, since the flows in these blood-perfused hearts are always heterogeneous (30), we used multicapillary analysis (26) to fit the data as well and obtained slightly better fits but no significant differences in parameter estimates. There was a tendency for the multicapillary analyses to give slightly higher estimates of PScap and lower estimates of PSpc than did single capillary analysis, but the overall conductance, which is 1/(1/PScap + 1/PScap), remained unchanged. The difference between potassium and thallium might also be due in part to a red cell carriage effect (31), if thallium were to exchange much more rapidly with red cells than does potassium, but we have no information on this.

Values for the maximum extraction, Emax, are given in Table 1. The average values for potassium and thallium were indistinguishable, 63% and 62%, with standard deviations of 11% and 12% (n = 19 and 24). Emax was less at higher flows. These values are lower than estimates obtained by residue detection without a reference tracer by Bergmann et al. (32). Our technique offers considerably greater precision in this estimate. Our E(t)’s are also distinctly lower than the 88% obtained by Weich et al. (33) at lower flows than ours. Their myocardial extractions fell to less than 60% when flow was increased fivefold, which is compatible with our estimates of PScap.

TABLE 1.

Parameter Values for K+ and Tl+ Exchange*

| Emax |

PScap |

PSpc |

γ |

Θ |

CV |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Experiment no. | FS | Hct | K | Tl | K | Tl | K | Tl | K | Tl | K | Tl | K | Tl |

| 090461 | 0.34 | 0.25 | 0.70 | 0.65 | 0.45 | 0.30 | 0.98 | 12.40 | 6.50 | 5.37 | 131 | 387 | 0.073 | 0.059 |

| 090462 | 0.59 | 0.25 | 0.70 | 0.57 | 0.82 | 0.48 | 2.62 | 5.73 | 7.01 | 7.01 | 153 | 312 | 0.086 | 0.039 |

| 090463 | 0.89 | 0.25 | 0.59 | 0.55 | 0.86 | 0.68 | 0.98 | 3.38 | 8.00 | 6.55 | 86 | 312 | 0.040 | 0.036 |

| 090464 | 1.20 | 0.25 | 0.52 | 0.61 | 1.02 | 1.20 | 0.57 | 4.26 | 7.42 | 6.91 | 329 | 324 | 0.030 | 0.036 |

| 090466 | 0.45 | 0.25 | 0.66 | 0.56 | 0.59 | 0.46 | 0.56 | 1.04 | 7.45 | 4.88 | 87 | 329 | 0.080 | 0.122 |

| 150183 | 0.45 | 0.40 | 0.81 | 0.85 | 1.01 | 1.05 | 1.98 | 3.99 | 5.38 | 5.38 | 69 | 63 | 0.045 | 0.034 |

| 150184 | 0.48 | 0.37 | 0.76 | 0.83 | 0.81 | 0.96 | 2.09 | 9.71 | 6.02 | 6.02 | 85 | 167 | 0.068 | 0.043 |

| 170181 | 0.84 | 0.37 | 0.67 | 0.67 | 0.92 | 0.96 | 5.32 | 11.20 | 6.28 | 5.83 | 191 | 791 | 0.187 | 0.044 |

| 170182 | 0.60 | 0.39 | 0.82 | 0.78 | 1.15 | 0.93 | 3.56 | 6.25 | 5.98 | 9.21 | 958 | 1149 | 0.051 | 0.035 |

| 170183 | 0.61 | 0.39 | 0.72 | 0.67 | 0.75 | 0.64 | 3.97 | 10.10 | 5.91 | 5.97 | 314 | 484 | 0.196 | 0.136 |

| 170271 | 0.61 | 0.28 | 0.65 | 0.77 | 0.66 | 0.93 | 5.96 | 12.20 | 5.01 | 4.96 | 389 | 392 | 0.110 | 0.117 |

| 170272 | 0.61 | 0.28 | 0.65 | 0.75 | 0.63 | 0.85 | 6.08 | 10.10 | 5.02 | 5.00 | 299 | 564 | 0.082 | 0.125 |

| 170274 | 1.22 | 0.24 | 0.55 | 0.62 | 0.97 | 1.21 | 5.84 | 12.20 | 6.59 | 4.27 | 114 | 565 | 0.122 | 0.081 |

| 170275 | 2.04 | 0.21 | 0.42 | 0.49 | 1.28 | 1.45 | 2.64 | 14.00 | 5.99 | 5.69 | 467 | 341 | 0.097 | 0.080 |

| 170276 | 2.09 | 0.21 | 0.51 | 0.53 | 1.57 | 1.61 | 13.80 | 11.90 | 5.08 | 5.08 | 297 | 483 | 0.178 | 0.124 |

| 200174 | 0.50 | 0.25 | 0.51 | 0.60 | 0.37 | 0.47 | 5.43 | 11.90 | 5.74 | 5.24 | 354 | 524 | 0.053 | 0.156 |

| 200175 | 0.99 | 0.26 | 0.58 | 0.86 | 11.80 | 5.41 | 427 | 0.148 | ||||||

| 200176 | 1.04 | 0.28 | 0.48 | 0.61 | 12.90 | 6.81 | 690 | 0.090 | ||||||

| 281062 | 0.66 | 0.37 | 0.56 | 0.51 | 11.50 | 5.71 | 479 | 0.144 | ||||||

| 281063 | 0.66 | 0.37 | 0.61 | 0.71 | 0.76 | 1.02 | 1.98 | 2.86 | 7.88 | 4.14 | 717 | 794 | 0.140 | 0.134 |

| 281064 | 1.15 | 0.43 | 0.42 | 0.59 | 12.40 | 5.68 | 523 | 0.105 | ||||||

| 281065 | 1.18 | 0.38 | 0.54 | 0.58 | 1.27 | 1.06 | 1.57 | 12.80 | 4.69 | 5.59 | 735 | 485 | 0.047 | 0.101 |

| 281066 | 1.59 | 0.35 | 0.42 | 0.82 | 13.30 | 6.92 | 917 | 0.096 | ||||||

| 281067 | 1.43 | 0.35 | 0.46 | 0.60 | 1.06 | 1.30 | 1.86 | 11.70 | 6.92 | 4.31 | 34 | 193 | 0.055 | 0.146 |

| Mean | 0.63 | 0.62 | 0.89 | 0.87 | 3.57 | 9.57 | 6.26 | 5.75 | 306 | 487 | 0.092 | 0.093 | ||

| s.d. | 0.11 | 0.12 | 029 | 0.33 | 3.04 | 3.84 | 0.97 | 1.08 | 251 | 241 | 0.050 | 0.042 | ||

| N | 19 | 24 | 19 | 24 | 19 | 24 | 19 | 24 | 19 | 24 | 19 | 24 | ||

Units for FS, PScap, and PSpc are in ml min−1 g−1; others are dimensionless. γ = Visf/Vcap. Θ = Vpc/Vcap. Based on Vcap = 0.042 ml g−1 a γ = 6.0 is equivalent to Visf of 0.25 ml g−1 and Θ = 400 is equivalent to . In five studies, 42K-CI was not available.

Plots of the logarithms of the ratios of concentrations of permeating to reference tracer, CD(t)/CR(t), or hD(t)/hR(t) have the advantage of displaying the data over long times. If E(t) were completely flat then the ratio CK/Calb would also be constant, as is evident from E(t) = 1 − hD(t)/hR(t). In the special situation where there is little or no return from the extravascular region into the outflowing blood, implicit in Equation 3, the ratio hK(t)/hR(t) can be interpreted directly:

| Eq. 7 |

(It is the initial value of this log ratio plot that Martin and Yudilevich (34) used for obtaining the estimates of PScap. This was an empirical attempt to account for return flux from the ISF to capillary in the presence of a barrier limitation.)

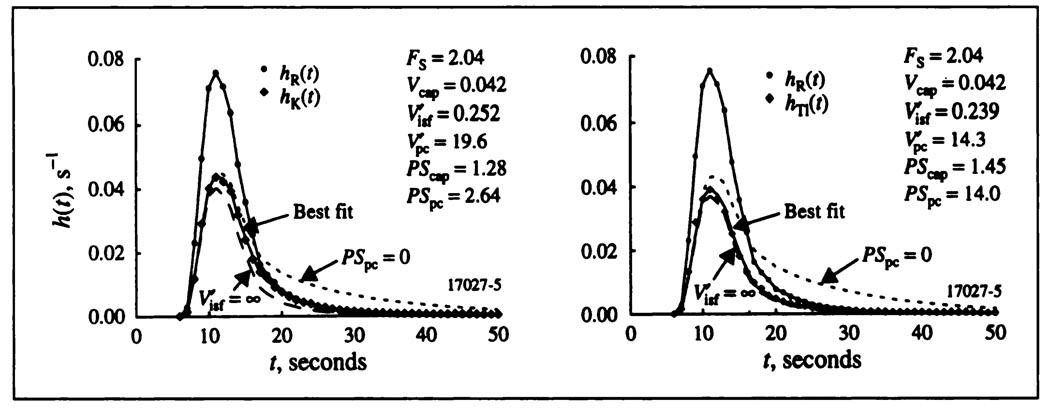

Estimation of Parameters Governing the Exchange

Best fits for a typical pair of potassium and thallium curves are shown in Figure 3. The capillary permeability surface area products, PScap, for potassium and thallium were similar. The dramatic difference is that the thallium PSpc’s are higher than those for potassium.

FIGURE 3.

Coronary sinus outflow dilution curves for albumin, potassium (left) and thallium (right), all obtained simultaneously in an isolated supported blood perfused dog heart. The potassium and thallium curves were fitted with a mass conservative single capillary-ISF-cell model. Parameters obtained for the best fits of the model to the data are given in the figure. Short dashes represent the curve for zero cellular uptake, PSpc = 0. Long dashes, labeled , represent the case where the cellular uptake is infinitely rapid with no return flux from ISF to capillary, which would be expected if the Crone-Renkin expression, Equation 1a, were applicable to the data.

Estimates of PScap from model fitting can be compared to estimates obtained with Equation 3, the Crone-Renkin equation based on the absence of a return flux, “backdiffusion” from ISF to plasma. The hypothetical case is shown in Figure 3 by the dashed lines, . Making the infinitely large means that there is no return flux from the ISF to the capillary, so that the dashed line has exactly the same shape as hR(t) but is scaled by 1 − e−PScap/F, one minus the fraction escaping. The difference between the curve for for thallium and the best fitting curve for thallium is very small, but is much larger for potassium. The rapid cellular uptake of thallium reduces its return flux. The Crone-Renkin expression, Equation 3, therefore gives an estimate of PScap for thallium quite close to that from the model, whereas it underestimates PScap for potassium. The observed values of maximal extraction, Emax, are given in the Table 1. The ratios of the estimates of the PScap for thallium by Equation 3 to that for the single-capillary model were 0.99 ± 0.10 (s.d., n = 24) and for potassium 0.90 ± 0.09 (s.d., n = 19); that is, the Crone-Renkin expression underestimated PScap compared to the single capillary model by 1% for thallium and 10% for potassium. Thus, the underestimation of PScap by Equation 3 is not great for indicators with large PSpc and cellular retention. This is in contrast to the use of PScap for sodium, where the rate of entry into cells is low and for which the equation was modified to PScap = −FS loge(1 − 1.14Emax) to correct for backdiffusion (12).

The other hypothetical case shown in Figure 3 is for no cellular uptake, PSpc = 0: the return flux from the ISF to the capillary is greater, and the area of the curve is 1.0. This is a reduction of the capillary-ISF-cell model to the capillary-ISF model with axial diffusion (5) or without (16, 17). If data prior to 15 or 20 sec were fitted with these reduced models, the estimates of PScap would be higher, particularly for thallium. However, to account for some backdiffusion yet provide long retention, one must use a model with cellular uptake.

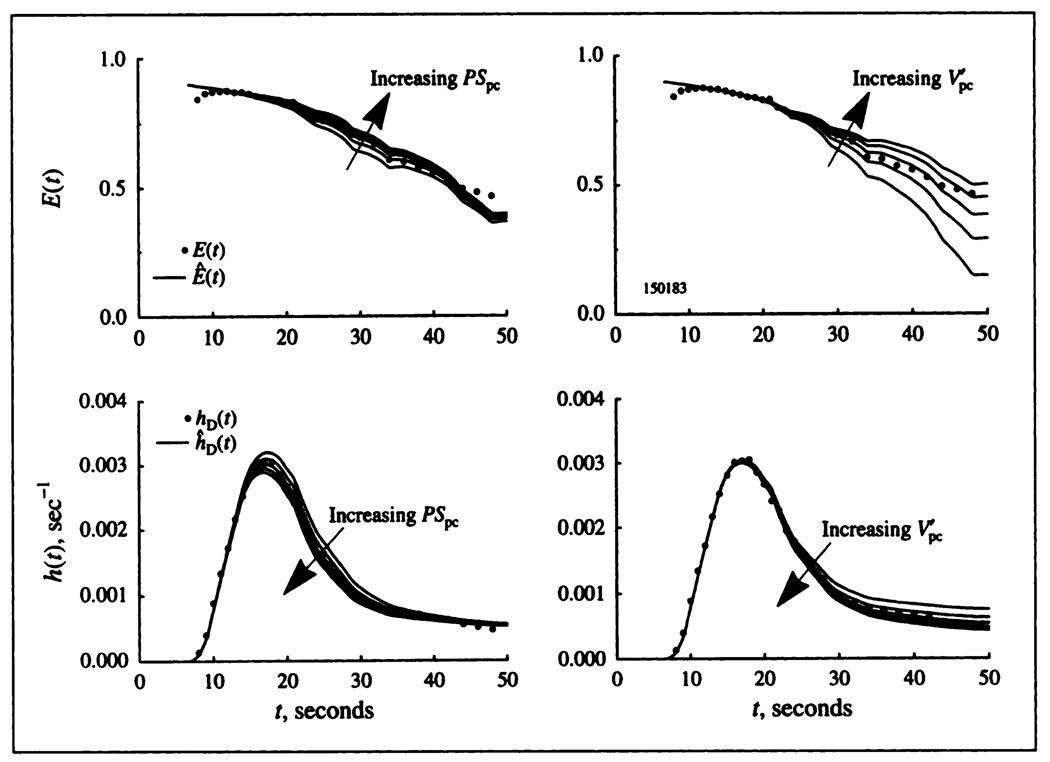

Distinguishability of the Parameters

The fitting of the model to the data gives parameter estimates that are well constrained. (Fits are “best”, not “unique.” The word unique is inappropriate since the definition of the “best” fit is dependent upon the method of calculating the difference between model solution and experimental data: linear least squares, logarithmic, etc. However, there is only one region of parameter space that gives “good” fits, and we do not experience getting trapped in local minima.) To estimate parameters by fitting the model to the data, the influences of the parameters on the shapes of the model solutions must differ from one another. Increases in PScap influence the upslope and peak of hTl(t), causing a reduction in the height of the throughput (nonextracted) fraction of the tracer. The corollary is that the same reduction of PScap leads to a heightening of the tail of the curve since the total area must still be unity. The left panel of Figure 4 shows that the influence of PSpc begins later and influences the peak height but mainly the early downslope. The right panel of Figure 4 shows that the influence of begins still later, has less influence than PSpc on the early part of the downslope and has its most marked influence late on the curve. Thus, the influences of PScap, PSpc, and are readily distinguishable. The influence of (not diagramed) is small because of the high rate of cellular uptake. was determined more accurately from the potassium curves where the cell uptake rate was lower.

FIGURE 4.

Influences of PSpc, and on the shapes of hD(t) and E(t) for a thallium dilution curve obtained from a blood-perfused dog heart. For all panels, FS = 0.45, Vcap = 0.042, , and PScap = 1.05. Left panels: and PSpc varies from 2.99 to 4.99 in steps of 0.5. Influence of PSpc is negligible in the first seconds of the upslope; it is maximal between the 20th and 30th sec and then diminishes. The best fit is with PSpc = 3.99 ml min−1 g−1. Higher values of PSpc, at 4.45 and 4.99 ml min−1 g−1 lower hD(t) and raise E(t); lowering PSpc to 3.49 and 2.99 ml min−1 g−1 produces the opposite effect, but more strongly, indicating the nonlinearity of the fitting problem. Right panels: PSpc = 3.99 and varies from 1.63 to 3.63in steps of 0.5. Increasing reduces the return flux from cell to ISF to venous outflow, lowering hD(t) and raising E(t) at these later times.

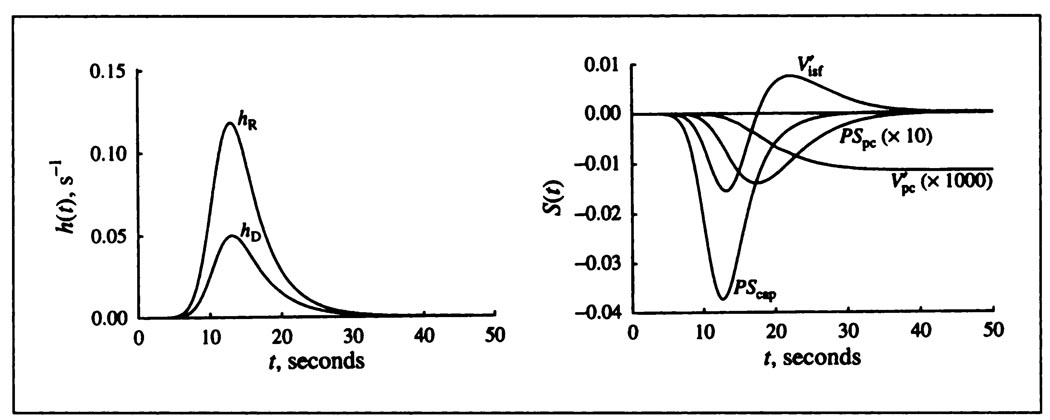

The distinguishability of parameters can be defined quantitatively by the use of sensitivity functions, such as those illustrated in Figure 5, which give at each time point a measure of the relative influences of each parameter on the shape of the model solution, hD(t). They are defined Sj(t) = ∂ĥD(t)/∂pj, where ĥD(t) is the model solution and pj is the value of the jth parameter of the model: Sj(t) describes, as a function of time, the magnitude and direction, up or down, of the influence on ĥD(t) of a small change in the value of the parameter. The sensitivity functions all have differing shapes. Opposite signs of two sensitivity functions, e.g., those of PScap and at t = 22 sec in the figure, mean that these two have opposing influences on hD(t). Sharp peaks in sensitivity functions indicate that higher data sampling rates are required at early times. The sensitivity functions are used in parameter adjustment, optimizing the fit of the model solution to the data (36). Figure 5 demonstrates that the free parameters have distinctly different sensitivity curves and that they can be estimated from data having sufficient accuracy and frequency of sampling.

FIGURE 5.

Solutions (left) and sensitivity functions (right) for the blood-tissue exchange model. Left panel: Impulse responses for a system consisting of arteries, veins and a capillary-tissue unit series. Input is a lagged normal density function with mean transit time 12 sec, relative dispersion 0.37 and skewness 1.4 (35). For the intravascular reference hR(t), the capillary mean transit time was 2.52 sec. The curve hD(t) is for the permeating tracer. The flow FS was 1.0 ml min−1 g−1: PScap and PSpc are 1 and 4 ml min−1 g−1, are 0.2 and 20 ml g−1. Right panel: Sensitivity functions for each of the governing transport parameters. The times of maximal influence are seen to be ordered in accordance with the sequence of solute transport from blood into the cells. For display, the S(t) for PSpc is scaled up ten times compared to the ordinate scaling and by a thousand times. While sensitivity to is less than that for the other parameters, it is almost the sole influence on the height of the tail.

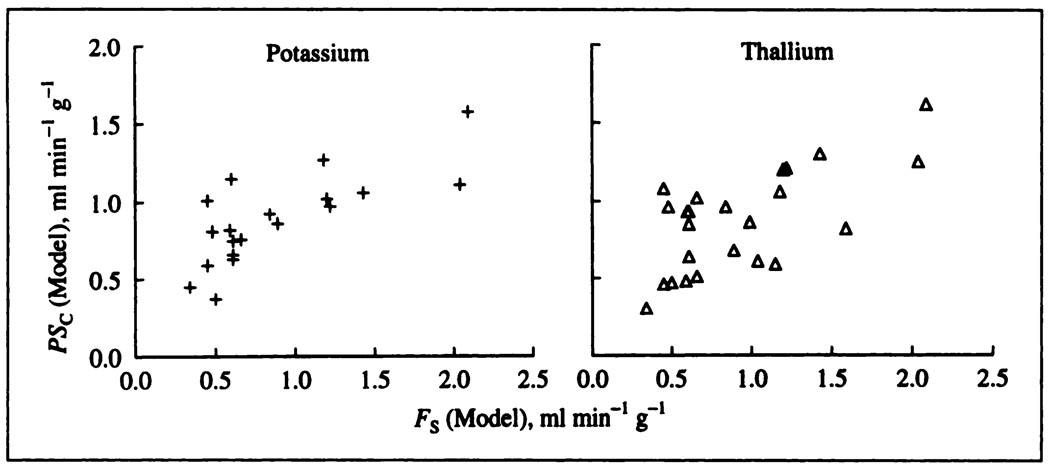

Capillary Permeability-Surface Area Products

Estimates of PScap obtained by fitting with the single capillary model are listed in Table 1 and plotted in the lower panels of Figure 6 against the plasma flow, the flow of solute-containing mother fluid, FS. For both K+ and Tl+, there is a modest increase in PScap with higher flows, presumably due to some recruitment of surface area at higher flows.

FIGURE 6.

The PScap’s for potassium (crosses) and thallium (triangles) both increase with higher flows in these blood-perfused dog hearts.

The ratios of potassium to thallium PScap’s averaged 1.02 ± 0.27 (s.d., n = 19) and were unaffected by the flow, but there is much scatter. (This s.d. of 27%, although large, is less than twice the minimal error in using the Fick technique for measuring cardiac output, about 15%. These experiments were not designed to test repeatability, so one would expect to improve on this variation if one did repeated observations.) The ratio of the free diffusion coefficients is 1.015. The similarity of the ratios of PScap’s to the free diffusion coefficients does suggest, despite the scatter, that the primary route of transport is through the interendothelial clefts, basically aqueous channels. It also makes it unlikely that uptake into red cells or endothelial cells is consequential, since the uptake rates would have to be exactly the same for both K+ and Tl+ to give this result, which seems improbable. There is no inference here that these molecules are small compared to the channels, although they surely are, whether these be through a fibre matrix within intercellular clefts (37) or through simpler pores, but only that steric factors would be the same for both.

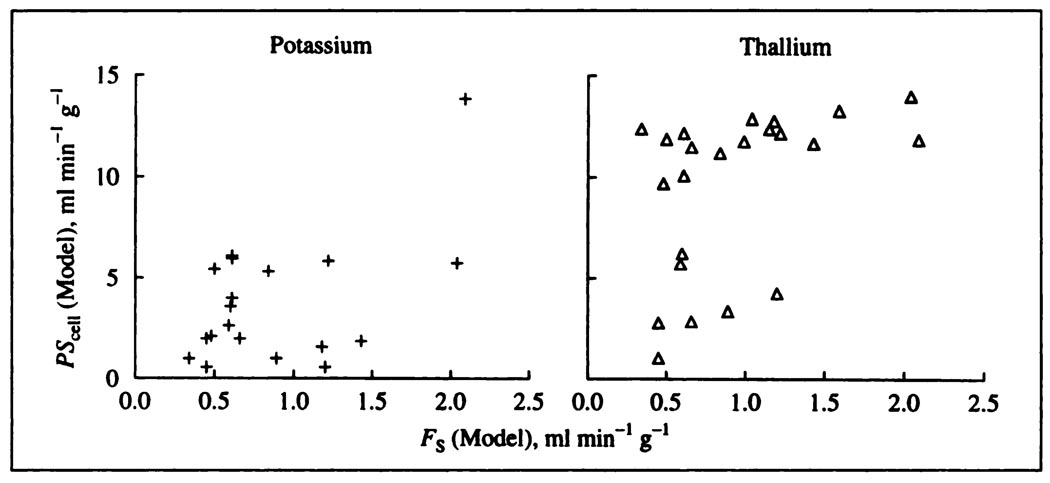

Estimates of Cellular Uptake Rates

Figure 7 shows the estimates of PSpc for potassium and thallium. While PSpc’s cannot be so accurately estimated as PScap’s, it is clear that sarcolemmal PSpc for both tracers is significantly higher than for PScap. For neither potassium nor thallium does there appear to be an effect of the flow on PSpc, which suggests that an increase in flow does not increase the accessibility of the cells to intravascular tracer. The same cellular membrane surface area was presumably available over the whole range of flows, independent of whether or not all of the capillaries were perfused at lower flows. This is reasonable since, in hexagonal arrays of capillaries and cells with a capillary/cell rate of unity, absence of flow in two capillaries leaves four others to supply the cell. The large degree of scatter could easily mask a subtle influence. The ratios of potassium to thallium PSpc’s averaged 0.44 ± 0.25 (n = 19); with the extreme value in experiment 170276 omitted, this ratio was 0.40 ± 0.19 (n = 18).

FIGURE 7.

Sarcolemmal permeability-surface area products for potassium (crosses) and thallium (triangles) in the blood-perfused dog heart Estimates were obtained via the single-capillary distributed convention-permeation model. The values of PSpc for Tl+ are considerably higher than for K+, but neither appear to be influenced by mean coronary blood flow.

DISCUSSION

Particular features of interest in these data are the similarity in rates of transport for thallium and potassium across the capillary barrier and the much higher rate of cellular uptake for thallium than for potassium at the parenchymal cell. Both capillary and sarcolemmal barriers impede the delivery of the tracers into the intracellular sink, a point which bears directly on the use of thallium and of the potassium analog rubidium as markers for regional myocardial blood flow by tracer imaging. The general observation that initial uptake of thallium exceeds that of potassium was made by L’Abbate et al. (38); here we offer high resolution observations that allow deeper explanation.

The similarity of PScap’s for the two tracers suggests that the rate of escape from the capillary is primarily through passive diffusive transport via aqueous channels between endothelial cells, and not across the endothelial cell membranes. The main argument is that the ratios of PScap’s are similar to the ratios of the free diffusion coefficients. Since the surface area of endothelial cells is about 104 times that of the aqueous channels, it seems safe to conclude that there is insignificant entry of K+ and Tl+ into the endothelial cells during the time of a single capillary traversal since, if there were endothelial uptake, it would likely be, as for the parenchymal cell, much greater for thallium. Support for this conclusion can also be taken from observations in other studies of the PScap’s for other small molecules in the blood-perfused dog heart. The estimates obtained by Alvarez and Yudilevich (39) on a set of small hydrophilic molecules including Na+ and Rb+, and by Durán and Yudilevich (40) on sucrose and sodium, in preparations similar to ours, are compatible with our estimates on PScap(K+) and PScap(Tl+). Comparison with previous data from our own laboratory on Na+ permeability in the same experimental preparation is also supportive; the estimates of Guller et al. (12) for PScap(Na+) averaged 1.0 ml min−1 g−1 compared to the averages for K+ and Tl+ of 0.82 and 0.87 ml min−1 g−1 obtained in this study.

The data do not exclude another possibility, however unlikely: the combination of a higher PScap for thallium than for potassium combined with a red cell carriage effect, also higher for thallium. The entry of the tracer into red cells renders it less available to traverse the capillary membrane (31,41) This idea is compatible with the forms of those curves which had a higher earlier peak for 201Tl than for 42K and a delayed rise in E(t) so that Emax for 20Tl occurred later than for 42K. This would make less thallium free to leave the capillary so that its capillary permeability PScap might be underestimated. Our analysis did not include consideration of entry into red cells, and since the effect could not have been large in any case, this minor question has been left open.

The higher values of myocyte sarcolemmal permeability PSpc for 201Tl than for 42K might deserve comment. Could 201Tl have a higher affinity for transport by the Na-K ATPase or through the ionic channels than does potassium? These data appear to be the first direct evidence in the heart that thallium is taken up more readily than potassium, but the relative rates are in accordance with the findings of Hille (42) who showed that permeability to thallium was 3.8 times that of potassium through the tetrodotoxin-sensitive Na+ channels and was in fact 0.33 times that for Na+ itself in myelinated nerve. In Hille’s experiments, the K+ channel was blocked by tetraethylammonium bromide so that these channels were not available for the carriage of ionic currents; in the presence also of TTX, the currents diminished to zero. In our beating heart preparation, the Na channels were certainly activated and clearly can account for much thallium transport if the analogy to the nerve applies, but it also seems probable that thallium might be transported via the potassium channels. We do not know of studies of thallium currents in TTX-blocked nerves or muscles, but the experiments can certainly be done.

Transport by the Na-K ATPase ordinarily occurs with slower unidirectional rates of flux than does transport via ionic channels. However, Hougen and Smith (43) and Hougen et al. (44) showed that ouabain inhibited the uptake of rubidium by in vivo dog heart during controlled infusions giving a ouabain concentration in the plasma in steady state of about 10−8 M, and showed about a 90% inhibition of Rb+ uptake by 10−3 M ouabain. On the other hand, Winkler and Schaper (45) found that intracoronary infusion of ouabain for 20 min had at most only a minor effect on the transcapillary extraction of thallium, and a somewhat larger effect on both Na+ and K+; sodium uptake was enhanced and potassium uptake diminished. Judging by these observations, we would think it likely that thallium is transported mainly by the ionic channels for Na+ and perhaps for K+ as well. The latter possibility is analogous to a Ca2+/Sr2+ situation: strontium conductance through the channel for the “slow inward current” in ventricular muscle is greater than for the natural ion calcium. Further experiments need to be performed to distinguish between these various possible mechanisms for thallium conductance across the sarcolemma. The effort may well be merited, since information on mechanisms of transport may be elucidated, and since more information on the effects of various pathophysiological states on thallium uptake in the heart is needed to support its clinical use as an index of myocardial blood flow. An alternate transport route would be any channel, such as a gramicidin channel through which water and a cation can move. Dani and Levitt, however, found that thallium bound more tightly to the gramicidin channel than did potassium, slowing water permeability much more than did the same concentration of potassium (46) Accordingly, they calculated that the minimum diffusion coefficient for Tl in the pore was only 1.4 × 10−7 cm2/sec compared to 8.4 × 10−7 cm2/sec for potassium (46) From our experiments, however, thallium permeability is higher than potassium, indicating that the permeability is not through this type of channel. Rather, our results are closer to those of Reuter and Stevens (47): neurons of land snails showed Tl+ permeability to be about 1.3 times that for K+, again leading us to conclude that the transport occurs through the normal potassium channel.

A further complicating possibility is raised by more recent studies by Winkler and Schaper (48). The myocardial content of rubidium and thallium were observed during perfusion with constant inflow levels of both tracers; adding oubain to the perfusate caused a sudden loss of a large fraction of the 201Tl but only a small and slow loss of 86Rb. The implication is that a substantial fraction of the thallium is displaced from an extracellular binding site, perhaps even the NaKATPase. Krivokapich et al. (49) observed that anoxia caused cessation of 201Tl uptake (or even some loss) during constant 201Tl perfusion in isolated rabbit septa and also during tracer washout resulted in a surge in the effluent 201Tl concentration. This suggests that thallium retention is energy-dependent, and one might speculate that the thallium binding to the NaKATPase is energy-dependent.

From our estimates of PScap, , PSpc, and for thallium, one may predict the results of other experiments. The low values of PScap and PSpc provide an explanation for the observations of incomplete extraction in the heart (32, 33, 50) Similarly Budinger et al. (51) have shown a strong decrease in rubidium extraction with higher flows.

When extraction is impeded by barriers, one would expect a curvilinear relationship between regional deposition of Tl+ and regional blood flows such as was shown by Renkin (7,8); extraction and retention diminished at higher flows. This is clearly observable with rubidium and potassium, and it is therefore interesting that thallium, the one entering parenchymal cells the most readily, has been reported by Nielsen et al. (52) and Pohost et al. [(53, their Fig. 2] to give a deposition-flow relationship which curves only mildly above flows of 2 ml min−1 g−1. The slope of their data is not known since Tl+ deposition is presented as absolute activity per gram of tissue rather than as fraction of dose injected.

Four factors appear to be contributing to this near-linearity.

Moderate scatter (regression coefficients of 0.98) necessarily masks curvature, and the scatter is higher at higher flows.

The data were acquired about 4 min after Tl+ injection into left atrium and after 5 min of exercise in dogs with circumflex coronary artery occlusion. This means that the physiological conditions differ in the high-flow and low-flow regions and opens the possibility that these differing regional conditions, such as potassium loss in the ischemic regions reducing the size of the sink for Tl+, give rise to a near linear relationship by a combination of opposing factors.

All their curves show evidence of the effects of washout combined with recirculation; positive intercepts on the thallium axis by 6%–10% of the mean show Tl+ deposition in low-flow regions in excess of microsphere deposition. The excess, as a ratio, appears to be a factor of 2–5 times but for some data points is higher, there being substantial Tl+ in a sample with almost no microspheres. This could occur with vasodilation and collateral flow occurring during the later minutes when recirculation is occurring. Another possibility is that capillary collaterals allow Tl+ but not microspheres to penetrate an ischemic region. Recirculation, washing Tl+ out of high-flow regions and depositing it in low-flow regions, tends to lower the slope and raise the intercept; because of the absence of calibration of Tl+ deposition, the fractional washout is not evident from their data. Definitive experiments should be designed to test these various possibilities individually. Whether this nonzero intercept is caused by capillary collateral flow or by recirculation, the observation poses a conundrum: if these were the only factors causing deviation from linearity, the Tl+ versus micro-sphere curve would be concave upward not downward. The obvious factor for bringing down the high-flow end of the curve is washout, which is greater with higher flow (1,50,53).

The near-linearity may result from an increase in the capillary PScap in the higher flow regions. As in our Figure 6, PScap for K+ and Tl+ at high flow is somewhat higher than it is at low flows but does not go up in proportion to flow. Observations of the PScap’s for other hydrophilic solutes in the heart (12,29,40) also suggest recruitment, as also explored by Cousineau et al. (54).

Larger microspheres tend to be deposited preferentially in high flow regions compared to smaller spheres (30); this means that in low flow regions there may be deposition of a larger fraction plasma label or a smaller microsphere than of larger micro-spheres. This may be part of the explanation for the positive intercepts on graphs of Tl+ deposition versus microsphere deposition (53) or ratios of Tl+ to microspheres exceeding unity in low flow regions.

The retention of Tl+ in the tissue is governed by the intratissue volume of distribution and the conductance for blood-tissue exchange. When flow is infinitely high, the relevant overall conductance, PST, is for the capillary and cell membranes in series 1, and 1/PST = 1/PScap + l/PSpc. By using the average values from Table 1, PST ≃ 0.8 ml min−l g−l. When the flow, FS, is not infinitely high relative to PST, then its slowness also retards the washout so that the overall clearance is 1/(1/PST + 1/FS). The relevant volume of distribution is approximately , which is about 12.5 ml g−l. The time constant for washout, τwash, is therefore

| Eq. 8 |

From average values, τwash ≃ 30 min; the half-time for washout would be 0.69 τwash or about 20 min. This estimate is what would be expected in comparison with the rates of potassium washout observed at early times by Tancredi et al. (1) in similarly perfused dog hearts and by Bergmann et al. (32) for Tl+. However, these estimates are faster than are observed over longer times (1, 55, 56) Marshall et al. (27) found thallium washout from isolated rabbit hearts to fall to half the initial rates; the rate depended more on flow than did the rate of washout of 99mTc-MIBI. (Selective intracoronary injection is the only valid means of tracer introduction for consideration of washout. When there is recirculation of tracer, its re-uptake slows the net rate of washout. With intravenous injection, whole-body recirculation dominates so that myocardial washout simply follows plasma washout and gives no information about the heart per se.) Likewise, Leppo and Meerdink (57, 58) had shown that Tl+ uptake was higher than that for M1BI and that PSpc for Tl+ was higher than PScap; they did not have a comparison with potassium or rubidium. These data are therefore compatible with findings by Maublant et al. (59) in cultured myocardial cells that Tl+ uptake and loss were both faster than those for 99mTc-MIBI.

A further factor retarding washout is partial flow limitation; this becomes significant when PScap is high enough to allow the effluent capillary concentration to approach the interstitial concentration as it will be when PScap/FS is greater than unity. This is likely to explain the data of Marshall et al. (27): the initial washout is from ISF, the later washout is from the cells.

However, because PScap and, to a lesser degree, PSpc, are well determined from the outflow dilution curves in the first half minute or so, inaccuracy in the estimation of is the major remaining source of error. It is this estimate which is most improved by the use of the residue function analysis, such as obtained by external detection or long washout without recirculation. Our experiments provide data for only the first couple of minutes; the residue function R(t) can be calculated quite accurately from the outflow dilution curves using the formula, , but data collected by external detection over a few hour period would be much more definitive, given that recirculation is negligible or accounted for. As an example, three of the 3–4-hr long washout curves of Tancredi et al. (1), whose preparation was the same as used here, were analyzed using this model; the three were experiments 27089, 13039 and 25044 shown in Figure 4 and Table 2 of their paper. The curves were fitted by the model quite precisely, and gave estimates of the fractional washout rate within 10% of those reported earlier. The cellular volumes of distribution were apparently higher than in the present series, estimates of Θ being 436, 1091 and 354, compared to our current average of 306 (Table 1). This comparison suggests that our present analysis of the outflow dilution curves tends to underestimate the intracellular volumes of distribution; heterogeneities in flows (30, 60–62) and in would both give a tendency in this direction. Although there is good reason for accounting for flow heterogeneities in the model analysis (26), especially with either very low or very high extractions, at the intermediate levels found here for K+ and Tl+, the parameters are estimated in an almost unbiased fashion with the single capillary model.

CONCLUSION

This study has focused on the assessment of the degree of barrier limitation at the capillary wall and cell membranes in dog myocardium to cellular uptake and deposition of cationic solutes that have large intracellular volumes of distribution. The concepts apply to the deposition of other markers such as sestamibi. Markers that permeate the barriers more slowly than potassium and thallium will be of limited use as flow markers since their single-pass extraction is lower and recirculation greater.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We appreciate the help of Drs. Richard Kern, G.A. Holloway, D. Williams and E. Bouskela in the early experiments, and of J. Eric Lawson and Geraldine Crooker in the preparation of the manuscript. This research was supported by National Institutes of Health grants HL50238 and RR1243.

APPENDIX

NEGLECT OF RADIAL CONCENTRATION GRADIENTS

The modeling is based on the stated assumption that radial concentration gradients are negligible in capillary, interstitium and cell. This is basically a statement that the times required for equilibration between compartments are long compared to times for diffusional flattening of radial concentration profiles within regions.

The time for exchange to bring the concentration in a radially mixed region to 90% of the way toward the final equilibrium concentration with an adjoining region held at constant concentration is

| Eq. Al |

where the time constant of the process is V′/PS and V′ and PS are the volume and the barrier permeability-surface area product. [1 − exp (−2.303) = 90%.]

The time for diffusional equilibration to bring the center of a cylinder to within 10% of the concentration at the external surface is

| Eq. A2 |

taken for example from Figure 5.3 of Crank (63), where D is a diffusion coefficient, t is time and R is cylinder radius. A modification for a region bounded by concentric cylinders with inner and outer radii Ro and Ri is

| Eq. A3 |

Within the capillary itself the ratio of the time for the transmural exchange process to bring about capillary-ISF equilibration to that required for intraluminal diffusional relaxation of gradients is (2.3 Vcap/PScap/ = 2.3 D/PRcap = (2.3 × 2.35 × 10−5 cm2 s−1)/(0.33 × 10−4 × 2.5 × 10−4 cm2 s−1) 6500, where the effective D in plasma is 0.94 (310/298) × (η310/η298) × 1.84 × 10−5 = 2.35 cm2/sec, considering 0.94 to be the nonprotein fraction of plasma available for solute diffusion, (310/298) to be the temperature correction factor and (η310/η298) to be the viscosity correction factor, 0.89/0.68, the ratio of water viscosities at 25°C and 37°C. Rcap is capillary radius, 2.5 × 10−4 cm; Scap is surface area, 500 cm2 g−1 (19); and P is permeability calculated from PScap = 1 ml min−1 g−1, which is about the mean value found for K+ and Tl+ in this study (from Table 1). Since 2.3D/PRcap ≫ 1000, the diffusional process is more than 1000 times faster than the permeation process, and it is apparent that radial intracapillary gradients must be negligible locally.

Another way of framing the question of the importance of radial gradients within the capillary is to calculate the ratio of capillary transit time, Vcap/FS, to the same radial diffusional relaxation time, i.e., (Vcap/FS)/ = (0.035 ml g−1/0.0166 ml g−1 s−1)/[(2.5 × 10−4)2/(2 × 2.35 × 10−5)] = 1600. This is a radial Peclet number; the value of over 1000 means that local radial equilibration is 1000 times more rapid than axial transit and that radial intracapillary gradients can again be considered negligible. These ideas and conclusions are confirmed by the mathematical solutions to the convection-diffusion equations provided by Pollock and Blum (64) and Aroesty and Gross (65).

In the interstitial space, the diffusional equilibration still proceeds relatively rapidly compared to exchange. Taking a maximally large half-intercapillary distance of 10 µ and D = 25% of the free diffusion coefficient (18,21) t(90%) = (10 µ)2/(2 × 0.25 × 2.35 × 10−5 cm2 s−1) = 0.1 sec. Considering a more normal value of 17 µ, rather than 20 µ, between capillary centers, and that most of the myocyte sarcolemma lies within 3 µ of the capillary basement membrane, t(90%) for diffusion in ISF must really be closer to (3/10)2 × 0.1 s = 0.01 sec. The t(90%) for exchange of capillary with ISF (using = 0.15 ml g−1 and an overly high value of PScap of 2 ml min−1 g−1) is 2.3 × 60 × 0.15/2 = 10 sec; this means that in the worst case the exchange process is 100–1000 times slower than is diffusional dissipation of the intraregional concentration gradients.

Within the cells the same result occurs and allows the neglect of radial gradients in Equation 4, 5 and 6. By using D = 25% of 2.35 × 10−5 cm2 s−1, R = 6 µ, PSpc = 5 ml min−1 g−1 and the anatomic volume = 0.7 ml g−1, the t (90%) for diffusion is about 20 msec and the ratio of exchange time-to-diffusion time is

| Eq. A4 |

With diffusion 600 times as rapid as exchange, one can extrapolate to say that even in cells several times as large as these, one can safely neglect any gradients due to slow intracellular diffusion. Gonzalez-Fernandez and Atta (66) considered O2 diffusion with intracellular consumption. The combination results in radial gradients in the steady-state, a different case from the present circumstance; even there, however, they estimated that azimuthal gradients due to inequality of distances from capillaries could be safely neglected.

REFERENCES

- 1.Tancredi RG, Yipintsoi T, Bassingthwaighte JB. Capillary and cell wall permeability to potassium in isolated dog hearts. Am J Physiol. 1975;229:537–544. doi: 10.1152/ajplegacy.1975.229.3.537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yipintsoi T, Tancredi R, Richmond D, Bassingthwaighte JB. Myocardial extractions of sucrose, glucose, and potassium. In: Crone C, Lassen NA, editors. Capillary permeability (Alfred Benzon Symp. II) Copenhagen: Munksgaard; 1970. pp. 153–156. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bassingthwaighte JB, Chan IS, Wang CY. Computationally efficient algorithms for capillary convection-permeation-diffusion models for blood-tissue exchange. Ann Biomed Eng. 1992;20:687–725. doi: 10.1007/BF02368613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rose CP, Goresky CA, Bach GG. The capillary and sarcolemmal barriers in the heart: An exploration of labeled water permeability. Circ Res. 1977;41:515–533. doi: 10.1161/01.res.41.4.515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bassingthwaighte JB. A concurrent flow model for extraction during transcapillary passage. Circ Res. 1974;35:483–503. doi: 10.1161/01.res.35.3.483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ziegler WH, Goresky CA. Kinetics of rubidium uptake in the working left ventricle of the dog. Circ Res. 1971;29:208–220. doi: 10.1161/01.res.29.2.208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Renkin EM. Transport of potassium-42 from blood to tissue in isolated mammalian skeletal muscles. Am J Physiol. 1959;197:1205–1210. doi: 10.1152/ajplegacy.1959.197.6.1205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Renkin EM. Exchangeability of tissue potassium in skeletal muscle. Am J Physiol. 1959;197:1211–1215. doi: 10.1152/ajplegacy.1959.197.6.1211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Crone C. The permeability of capillaries in various organs as determined by the use of the “indicator diffusion’ method. Acta Physiol Scand. 1963;58:292–305. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-1716.1963.tb02652.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zierler KL. Equations for measuring blood flow by external monitoring of radioisotopes. Circ Res. 1965;16:309–321. doi: 10.1161/01.res.16.4.309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chinard FP, Vosburgh GJ, Enns T. Transcapillary exchange of water and of other substances in certain organs of the dog. Am J Physiol. 1955;183:221–234. doi: 10.1152/ajplegacy.1955.183.2.221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Guller B, Yipintsoi T, Orvis AL, Bassingthwaighte JB. Myocardial sodium extraction at varied coronary flows in the dog: Estimation of capillary permeability by residue and outflow detection. Circ Res. 1975;37:359–378. doi: 10.1161/01.res.37.3.359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Robinson RA, Stokes RH. Electrolyte solutions. 2nd ed. London: Butterworths; 1959. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ussing HH, Kruhoffer P, Thaysen JH, Thorn NA. Handbook of experimental pharmacology: the alkali metal ions in biology. Berlin: Springer-Verlag; 1960. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Korenman IM. Analytical chemistry of thallium. Ann Arbor: Humphrey Science Publ.; 1969. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sangren WC, Sheppard CW. A mathematical derivation of the exchange of a labeled substance between a liquid flowing in a vessel and an external compartment. Bull Math Biophys. 1953;15:387–394. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Goresky CA, Ziegler WH, Bach GG. Capillary exchange modeling: barrier-limited and flow-limited distribution. Circ Res. 1970;27:739–764. doi: 10.1161/01.res.27.5.739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Safford RE, Bassingthwaighte JB. Calcium diffusion in transient and steady states in muscle. Biophys J. 1977;20:113–136. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(77)85539-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bassingthwaighte JB, Yipintsoi T, Harvey RB. Microvasculature of the dog left ventricular myocardium. Microvasc Res. 1974;7:229–249. doi: 10.1016/0026-2862(74)90008-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Overholser KA, Harris TR. Effects of hyaluronidase and protamine on resistance and transport after coronary flow reduction in heparinized dogs. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1981;217:62–69. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Safford RE, Bassingthwaighte EA, Bassingthwaighte JB. Diffusion of water in cat ventricular myocardium. J Gen Physiol. 1978;72:513–538. doi: 10.1085/jgp.72.4.513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bridge JHB, Bersohn MM, Gonzalez F, Bassingthwaighte JB. Synthesis and use of radiocobaltic EDTA as an extracellular marker in rabbit heart. Am J Physiol. 1982;242(Heart Circ Physiol 11):H671–H676. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1982.242.4.H671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gonzalez F, Bassingthwaighte JB. Heterogeneities in regional volumes of distribution and flows in the rabbit heart. Am J Phvsiol. 1990;258(Heart Circ Physiol 27):H1012–H1024. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1990.258.4.H1012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kroll K, Bukowski TR, Schwartz LM, Knoepfler D, Bassingthwaighte JB. Capillary endothelial transport of uric acid in the guinea pig heart. Am J Physiol. 1992;262(Heart Circ Physiol 31):H420–H431. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1992.262.2.H420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Knopp TJ, Anderson DU, Bassingthwaighte JB. SIMCON—simulation control to optimize man-machine interaction. Simulation. 1970;14:81–86. doi: 10.1177/003754977001400205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.King RB, Raymond GM, Bassingthwaighte JB. Modeling blood flow heterogeneity. Ann Biomed Eng. 1996;24:352–372. doi: 10.1007/BF02660885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Marshall RC, Leidholdt EM, Jr, Zhang DY, Barnett CA. Technetium-99m-hexakis 2-methoxy-2-isobutyl isonitrile and thallium-201 extraction, washout and retention at varying coronary flow rates in rabbit heart. Circulation. 1990;82:998–1007. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.82.3.998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rose CP, Goresky CA. Vasomotor control of capillary transit time heterogeneity in the canine coronary circulation. Circ Res. 1976;39:541–554. doi: 10.1161/01.res.39.4.541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Harris TR, Overholser KA, Stiles RG. Concurrent increases in resistance and transport after coronary obstruction in dogs. Am J Physiol. 1981;240(Heart Circ Physiol 9):H262–H273. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1981.240.2.H262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yipintsoi T, Dobbs WA, Jr, Scanlon PD, Knopp TJ, Bassingthwaighte JB. Regional distribution of diffusible tracers and carbonized microspheres in the left ventricle of isolated dog hearts. Circ Res. 1973;33:573–587. doi: 10.1161/01.res.33.5.573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Goresky CA, Bach GG, Nadeau BE. Red cell carriage of label: its limiting effect on the exchange of materials in the liver. Circ Res. 1975;36:328–351. doi: 10.1161/01.res.36.2.328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bergmann SR, Hack SN, Sobel BE. “Redistribution” of myocardial thallium-201 without reperfusion: Implications regarding absolute quantification of perfusion. Am J Cardiol. 1982;49:1691–1698. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(82)90247-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Weich HF, Strauss HW, Pitt B. The extraction of thallium-201 by the myocardium. Circulation. 1977;56:188–191. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.56.2.188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Martin P, Yudilevich DL. A theory for the quantification of transcapillary exchange by tracer-dilution curves. Am J Physiol. 1964;207:162–168. doi: 10.1152/ajplegacy.1964.207.1.162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bassingthwaighte JB, Ackerman FH, Wood EH. Applications of the lagged normal density curve as a model for arterial dilution curves. Circ Res. 1966;18:398–415. doi: 10.1161/01.res.18.4.398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chan IS, Goldstein AA, Bassingthwaite JB. SENSOP: a derivative-free solver for nonlinear least squares with sensitivity scaling. Ann Biomed Eng. 1993;21:621–631. doi: 10.1007/BF02368642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Curry FE, Michel CC. A fiber matrix model of capillary permeability. Microvasc Res. 1980;20:96–99. doi: 10.1016/0026-2862(80)90024-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.L’Abbate A, Biagini A, Michelassi C, Maseri A. Myocardial kinetics of thallium and potassium in man. Circulation. 1979;60:776–785. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.60.4.776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Alvarez OA, Yudilevich DL. Heart capillary permeability to lipid-insoluble molecules. J Physiol. 1969;202:45–58. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1969.sp008794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Durán WN, Yudilevich DL. Estimate of capillary permeability coefficients of canine heart to sodium and glucose. Microvasc Res. 1978;15:195–205. doi: 10.1016/0026-2862(78)90018-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Roselli RJ, Harris TR. A four-phase model of capillary tracer exchange. Ann Biomed Eng. 1979;7:203–238. doi: 10.1007/BF02364115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hille B. The permeability of the sodium channel to metal cations in myelinated nerve. J Gen Physiol. 1972;59:637–658. doi: 10.1085/jgp.59.6.637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hougen TJ, Smith TW. Inhibition of myocardial monovalent cation active transport by subtoxic doses of ouabain in the dog. Circ Res. 1978;42:856–863. doi: 10.1161/01.res.42.6.856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hougen TJ, Lloyd BL, Smith TW. Effects of inotropic and arrhythmogenic digoxin doses and of digoxin-specific antibody on myocardial monovalent cation transport in the dog. Circ Res. 1979;44:23–31. doi: 10.1161/01.res.44.1.23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Winkler B, Schaper W. Tracer kinetics of thallium, a radionuclide used for cardiac imaging. In: Schaper W, editor. The pathophysiology of myocardial perfusion. Amsterdam: Elsevier/North Holland; 1979. pp. 102–112. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Dani JA, Levitt DG. Water transport and ion-water interaction in the gramicidin channel. Biophys J. 1981;35:501–508. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(81)84805-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Reuter H, Stevens CF. Ion conductance and ion selectivity of potassium channels in snail neurones. J Membrane Biol. 1980;57:103–118. doi: 10.1007/BF01868997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Winkler B, Schaper W. The role of radionuclides for cardiac research. In: Pabst HW, Adam WE, Ell P, Hör G, Kriegel H, editors. Handbook of nuclear medicine. Vol. 2. Heart. Stuttgart, New York: Gustav Fischer; 1992. pp. 390–407. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Krivokapich J, Watanabe CR, Shine KI. Effects of anoxia and ischemia on thallium exchange in rabbit myocardium. Am J Physiol. 1985;249:H620–H628. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1985.249.3.H620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Grunwald AM, Watson DD, Holzgrefe HH, Jr, Irving JF, Beller GA. Myocardial thallium-201 kinetics in normal and ischemic myocardium. Circulation. 1981;64:610–618. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.64.3.610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Budinger TF, Yano Y, Huesman RH, et al. Positron emission tomography of the heart. Physiologist. 1983;26:31–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Nielsen AP, Morris KG, Murdock R, Bruno FP, Cobb FR. Linear relationship between the distribution of thallium-201 and blood flow in ischemic and nonischemic myocardium during exercise. Circulation. 1980;61:797–801. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.61.4.797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Pohost GM, Okada RD, O’Keefe DD, et al. Thallium redistribution in dogs with severe coronary artery stenosis of fixed caliber. Circ Res. 1981;48:439–446. doi: 10.1161/01.res.48.3.439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Cousineau DF, Goresky CA, Rose CP, Simard A, Schwab AJ. Effects of flow, perfusion pressure, and oxygen consumption on cardiac capillary exchange. J Appl Physiol. 1995;78:1350–1359. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1995.78.4.1350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Okada RD, Leppo JA, Strauss HW, Boucher CA, Pohost GM. Mechanisms and time course for the disappearance of thallium-201 defects at rest in dogs. Am J Cardiol. 1982;49:699–706. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(82)91949-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Okada RD, Jacobs ML, Daggett WM, et al. Thallium-201 kinetics in nonischemic canine myocardium. Circulation. 1982;65:70–77. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.65.1.70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Leppo JA, Meerdink DJ. A comparison of the myocardial uptake of a technetium-labeled isonitrile analog and thallium. Circ Res. 1989;65:632–639. doi: 10.1161/01.res.65.3.632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Leppo JA, Meerdink DJ. Comparative myocardial extraction of two technetium-labeled BATO derivatives (SQ30217, SQ32014) and thallium. J Nucl Med. 1990;31:67–74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Maublant JC, Gachon P, Moins N. Hexakis (2-methoxy isobutylisonitrile) technetium-99m and thallium-201-chloride: uptake and release in cultured myocardial cells. J Nucl Med. 1988;29:48–54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Marcus ML, Kerber RE, Erhardt JC, Falsetti HL, Davis DM, Abboud FM. Spatial and temporal heterogeneity of left ventricular perfusion in awake dogs. Am Heart J. 1977;94:748–754. doi: 10.1016/s0002-8703(77)80216-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.King RB, Bassingthwaighte JB, Hales JRS, Rowell LB. Stability of heterogeneity of myocardial blood flow in normal awake baboons. Circ Res. 1985;57:285–295. doi: 10.1161/01.res.57.2.285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Bassingthwaighte JB, Malone MA, Moffett TC, et al. Molecular and particulate depositions for regional myocardial flows in sheep. Circ Res. 1990;66:1328–1344. doi: 10.1161/01.res.66.5.1328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Crank J. The mathematics of diffusion. Oxford: Clarendon Press; 1956. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Pollock F, Blum JJ. On the distribution of a permeable solute during Poiseuille flow in capillary tubes. Biophys J. 1966;6:19–29. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(66)86637-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Aroesty J, Gross JF. Convection and diffusion in the microcirculation. Microvasc Res. 1970;2:247–267. doi: 10.1016/0026-2862(70)90016-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Gonzalez-Fernandez JM, Atta SE. Concentration of oxygen around capillaries in polygonal regions of supply. Math Biosci. 1972;13:55–69. [Google Scholar]