Abstract

Background:

Obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) may increase the risk of respiratory complications and acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) among surgical patients. OSA is more prevalent among obese individuals; obesity can predispose to ARDS.

Hypothesis:

It is unclear whether OSA independently contributes towards the risk of ARDS among hospitalized patients.

Methods:

This is a pre-planned retrospective subgroup analysis of the prospectively identified cohort of 5,584 patients across 22 hospitals with at least one risk factor for ARDS at the time of hospitalization from a trial by the US Critical Illness and Injury Trials Group designed to validate the Lung Injury Prediction Score. A total of 252 patients (4.5%) had a diagnosis of OSA at the time of hospitalization; of those, 66% were obese. Following multivariate adjustment in the logistic regression model, there was no significant relationship between OSA and development of ARDS (OR = 0.65, 95%CI = 0.32-1.22). However, body mass index (BMI) was associated with subsequent ARDS development (OR = 1.02, 95%CI = 1.00-1.04, p = 0.03). Neither OSA nor BMI affected mechanical ventilation requirement or mortality.

Conclusions:

Prior diagnosis of OSA did not independently affect development of ARDS among patients with at least one predisposing condition, nor the need for mechanical ventilation or hospital mortality. Obesity appeared to independently increase the risk of ARDS.

Citation:

Karnatovskaia LV, Lee AS, Bender SP, Talmor D, Festic E. Obstructive sleep apnea, obesity, and the development of acute respiratory distress syndrome. J Clin Sleep Med 2014;10(6):657-662.

Keywords: obstructive sleep apnea, obesity, acute respiratory distress syndrome

Acute respiratory distress syndrome remains a common cause of respiratory failure in intensive care units (ICU) with estimated mortality rate of over 40%.1,2 Given limited treatment options once the condition develops, the investigative paradigm is shifting towards identifying potential predis-posing conditions and implementation of secondary prevention strategies.3 While increased body mass index (BMI) may represent a predisposing factor for ARDS development,4 it is still unclear whether the closely associated condition, obstructive sleep apnea (OSA), independently contributes towards the risk of ARDS.

OSA is a growing health concern with prevalence estimates ranging between 3% to 24% in the general population.5,6 Similar rate of about 25% has been reported in surgical patients.7 OSA has been associated with an increased risk for the development of ARDS among patients undergoing surgery. In the largest review, of over 6,000,000 cases of orthopedic and general surgery procedures, 2.5% and 1.4% of patients had a diagnosis of OSA, respectively. The authors found that OSA was associated with a higher odds ratio (OR) of developing ARDS: 2.39 for orthopedic and 1.58 for general surgery cases.8 A recent meta-analysis of thirteen trials reported a significant association of OSA and development of acute respiratory failure in surgical patients.9 OSA was found to be an independent risk factor for post-obstructive pulmonary edema in patients requiring tracheostomy.10 Patients with OSA requiring surgery have been shown to have a higher rate of pulmonary complications11–13 with hypoxemia being most common,14–17 even following adjustment for BMI.14,17

BRIEF SUMMARY

Current Knowledge/Study Rationale: OSA and obesity are known risk factors for respiratory complications/ARDS following surgery. It is unclear whether OSA independently contributes towards the risk of ARDS among all hospitalized patients.

Study Impact: Among patients with at least one predisposing condition, diagnosis of OSA prior to hospitalization did not independently affect the risk of progression to ARDS. Obesity appeared to independently increase the risk of ARDS.

Perhaps the most challenging part in clarifying the potential role of OSA on predisposition to develop ARDS is to tease out any independent effect of obesity on ARDS as up to 94% of patients requiring bariatric surgery may have a concomitant diagnosis of sleep apnea.18 While some studies indicate that a higher BMI may confer an increased risk of ARDS,4,19 others reported a lower rate of ARDS among obese patients.20

Since the treatment of ARDS is significantly limited once the condition is established, the mission of the US Critical Illness and Injury Trials Group - Lung Injury Prevention Study (USCIITG-LIPS) investigators has been to identify modifiable risks for ARDS and potential strategies to prevent its occurrence. Given the high prevalence of OSA in general population, we aimed to better define the association between OSA and ARDS. To date, there have not been any studies specifically examining the effect of OSA diagnosis on the subsequent development of ARDS among patients at risk. Additionally, we aimed to better define the interrelationship between OSA, obesity, and ARDS. To explore this, we performed a secondary analysis of a large prospective cohort of patients requiring hospitalization to estimate the risk of pre-hospital diagnosis of OSA, as well as obesity, on the development of ARDS.

METHODS

The USCIITG investigated 5,584 patients admitted to 22 hospitals in order to evaluate the Lung Injury Prediction Score (LIPS).3 With the exception of three centers, all data was collected prospectively. The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board at each participating location. The current study is a pre-planned subgroup analysis of the prospectively identified LIPS cohort and was approved by the LIPS ancillary committee.

Study Population

Details of the study population have been previously described.3 Inclusion criteria were adult patients (> 18 years) who had at least one major risk factor for ARDS including sepsis, shock, pancreatitis, pneumonia, aspiration, high-risk trauma, or major cardiac and lung surgery. Exclusion criteria were acute lung injury (ALI) at the time of admission, transfer from an outside hospital, death in the emergency department, comfort or hospice care, or hospital readmission during the study period.3

Predictor Variables

The primary exposure of interest was a diagnosis of OSA documented in the medical record on admission, obtained from the “history and physical” form or directly from the patient or family members. The secondary pertinent exposure, BMI, was calculated based on admission height and weight. We stratified BMI into the following categories, as previously reported:4 underweight (BMI < 18.5 kg/m2), normal (BMI 18.5-24.9), overweight (BMI 25-29.9), obese (BMI 30-39.9), and severely obese (BMI > 40).

Information on severity of OSA and compliance with therapy was not collected. Demographic and clinical information were obtained at the time of hospital admission or preoperatively at the time of surgery. These data were used to calculate the LIPS score as a measure of the baseline risk of developing ARDS, and the Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation (APACHE) II score as a measure of disease severity.3

Outcome Variables

The main outcome was the development of ARDS during the hospitalization. At the time of data collection, the presence of ALI/ARDS was determined by the Standard American-European consensus conference criteria: development of acute, bilateral pulmonary infiltrates and hypoxemia (PaO2/FiO2 < 300 – ALI, PaO2/FiO2 < 200 – ARDS) in the absence of clinical signs of left atrial hypertension.21 However, since recent Berlin definition22 removed the term ALI and reclassified hypoxemia in the range of PaO2/FiO2 < 300 as ARDS, we use that term in reporting our results. Secondary outcomes included the need for invasive mechanical ventilation and mortality. Patients were followed for the duration of their hospital stay, up to 90 days.3

Statistical Analyses

Patients were separated into two groups on the basis of whether they had documented diagnosis of OSA at the time of hospital admission or not. We first performed univariate analysis to compare demographics, comorbidities, and medications between two groups. Each of the systematically collected clinical variables obtained in the LIPS database was compared between those with diagnosis of OSA and the rest of the cohort. We then determined the (unadjusted) OR of developing ARDS for patients with history of OSA compared to others. Contingency variables were compared using Fisher exact test, and the distribution of continuous variables was assessed with the t-test; ANOVA was used for multiple comparisons. We also performed univariate analysis examining each of the BMI categories and their respective unadjusted associations to ARDS.

Multivariate analyses using a logistic regression model were performed to determine the adjusted OR of developing ARDS. Similar analyses were repeated to evaluate the two exploratory secondary outcome variables. Covariates included the LIPS and the APACHE II scores, BMI, OSA, age, smoking status, alcohol use, cardiac surgery, brain injury, congestive heart failure NYHA stage IV, diabetes, pneumonia, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, asthma, gastroesophageal reflux disease, aspiration, use of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor/ angiotensin receptor blockers, statins, and inhaled steroids. The BMI variable was used in the initial logistic regression model as continuous variable and in the subsequent model we used four dummy variables per previously reported BMI cutoffs.

Risk assessments are reported as OR with 95% confidence intervals (CI). A p-value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant. All analyses were performed using JMP Pro 10.0.2 statistical software (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC).

RESULTS

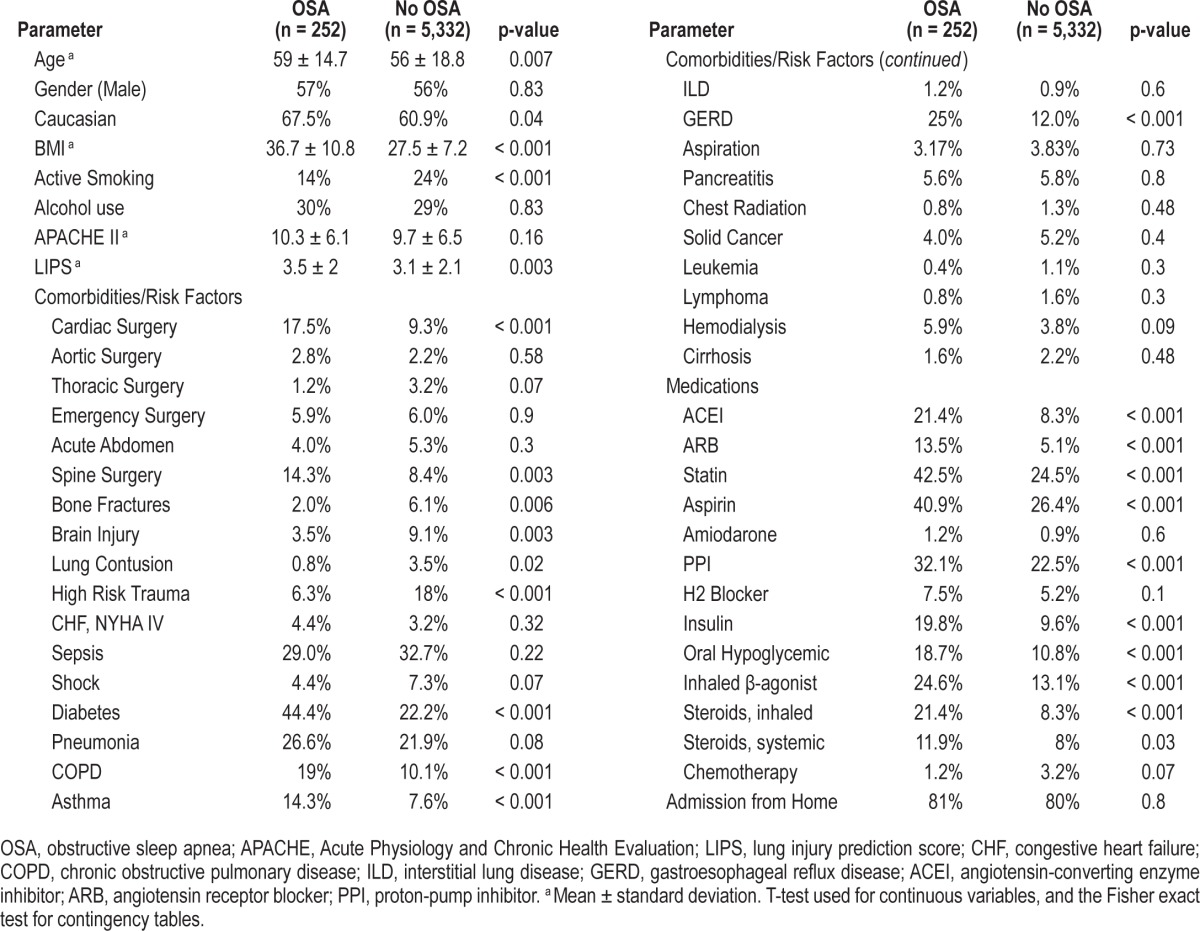

As previously described, 5,584 patients were enrolled into the LIPS study between March and August of 2009.3 The median age of the entire cohort was 57 years, and the majority was Caucasian and male. Of those patients, 252 (4.7%) had documented diagnosis of OSA at the time of hospitalization. Incidence of ARDS was 7.5% and 6.7 % (p = 0.61) for patients with and without a diagnosis of OSA, respectively. Univariate analysis showed that patients with OSA were more likely to be older, Caucasian, undergo cardiac and brain surgery, have diabetes, chronic pulmonary disease, and reflux. Those patients were also more likely to be on aspirin, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor, angiotensin receptor blocker, statin, proton pump inhibitor, hypoglycemic medication, and inhaled steroids. They had higher LIPS score and BMI and abused tobacco less frequently (Table 1). No baseline differences in APACHE II scores were present. Notably, 66% of OSA patients were obese (BMI > 30) compared to only 28% of those without the diagnosis of OSA (p < 0.001).

Table 1.

Group characteristics

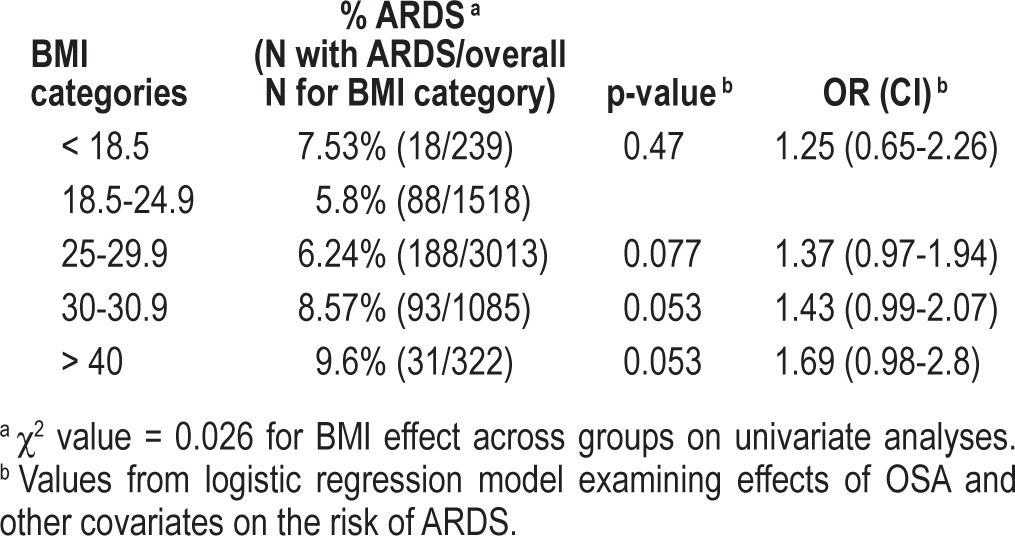

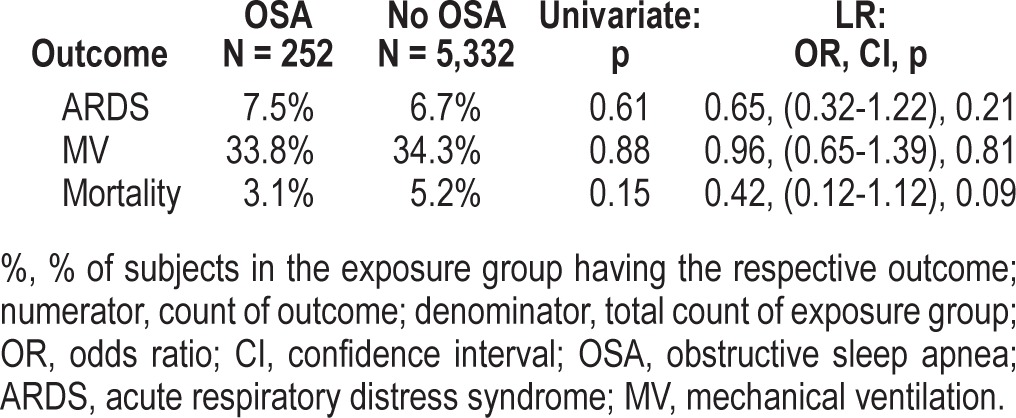

We included the following variables in the logistic regression model based on abovementioned statistically significant group differences and clinical importance: age, Caucasian, active smoking, alcohol use, LIPS, APACHE 2, cardiac surgery, brain injury, congestive heart failure New York Heart Association class IV, diabetes mellitus, pneumonia, aspiration, chronic obstructive lung disease, asthma, reflux, statin, aspirin, inhaled steroid use, sleep apnea, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor, angiotensin receptor blocker, BMI. Following multivariate adjustment in the logistic regression model, there was no observed significant association between OSA and development of ARDS (OR = 0.65, 95% CI = 0.32-1.22). However, there appeared to be significant association of BMI (as a continuous variable) with subsequent ARDS development, with an OR of 1.02 (95% CI = 1.00-1.04, p = 0.03) per single unit increase in BMI (1 kg/m2), which translates into estimated overall increase in risk of 22% for an increase in BMI by 10 units. However, when we stratified patients who developed ARDS into categories of BMI, greater BMI was associated with even greater risk of ARDS (Table 2). With regards to secondary outcomes, there were no significant differences in requirement for mechanical ventilation or an effect on mortality based on prior diagnosis of OSA (Table 3); there was also no significant association with BMI.

Table 2.

Relationship between BMI and ARDS across BMI categories in the logistic regression model

Table 3.

OSA and the risk for respiratory complications and death in the entire cohort and following adjustment by logistic regression

DISCUSSION

This is the first study to specifically evaluate the role of OSA in the development of ARDS among at-risk patients in a prospectively collected cohort. Initial unadjusted analysis revealed no difference in incidence of ARDS for patients with OSA compared to controls; however, obesity portended a greater risk. Following multivariate adjustment in logistic regression, there was no significant difference in incidence of ARDS between those with and without OSA diagnosis, nor was there a difference in the need for mechanical ventilation or mortality. Overall, higher BMI was associated with an increased risk of ARDS in the logistic regression model.

It is not surprising that we found a significant association between BMI and ARDS, as increased risk has been demonstrated previously.4,19 However, we could not replicate in our study previously reported risk of ARDS among patients with OSA. Given prevalence of obesity among patients with OSA, lack of a statistical association may be confounded by the rate of underdiagnosis of OSA in hospital and general population. Among surgical patients, of the 661 individuals who screened high risk for OSA, 81% did not have a prior diagnosis in one study.7 Others demonstrated that known OSA diagnosis was missed by surgeons and anesthesiologists in 58% and 15% of cases, respectively; when the remaining patients were administered polysomnography prior to surgery, 37.7% were found to have moderate to severe OSA.23 For the general population, current prevalence estimates of moderate to severe sleep disordered breathing are 10% among 30- to 49-year-old men; 17% among 50- to 70-year-old men; 3% among 30- to 49-year-old women; and 9% among 50- to 70-year-old women.24,25 Therefore, given average age (57) in our study population, the reported rate of diagnosed OSA of 4.7% in our cohort most likely underestimates the actual prevalence of OSA in those patients. Association between OSA and ARDS may have been further weakened by OSA treatment patients may have been receiving prior to admission.

Sixty-six percent rate of obesity in OSA patients in our study is consistent with recent reports.26 In examining why obese patients may have had higher incidence of ARDS, we reviewed ventilator data and found no significant differences in delivered tidal volumes, peak, and plateau pressures between patients with BMI greater and less than 30. We were not able to retrospectively report data on transpulmonary pressures as this was not routinely done at all participating centers. It is possible that insufficient PEEP relative to transpulmonary pressure in obese individuals may have contributed to atelectrauma. With regards to rates of pneumonia as a potential contributor, documented incidence of pneumonia was lower in patients with BMI > 30 compared to controls, so pneumonia could also not explain increased incidence of ARDS in obese subjects. Moreover, we have not found any difference in the rate of aspiration between the two groups. Interestingly, a higher prevalence of obese subjects with diabetes in the OSA group did not translate into an expected reduction in lung injury as previously described.27 Therefore, other mechanisms may have played a role in observed findings.

Obese patients may experience such alterations in pulmonary mechanics as airflow obstruction, decreased lung volumes, and impaired gas exchange, all of which may predispose them to develop ARDS.28 Additionally, adipose tissue is an active endocrine organ secreting bioactive molecules called adipokines. Obesity is characterized by an overproduction of proinflammatory adipokines (leptin, resistin) and a lower production of anti-inflammatory adipokines (adiponectin).29 Additionally, obesity is associated with an increase in formation of reactive oxygen species (ROS).30 However, since many of those with OSA are not obese,31 mechanisms of OSA effect on propensity to develop ARDS may be both interdependent and independent of those described in obesity.

OSA also represents a pro-inflammatory state with increased levels of IL-6 and IL-832; higher IL-8 levels are associated with increased risk of development of acute lung injury.33 Others observed an increase in KL-6 levels in patients with more severe OSA.34,35 Elevation of KL-6 has previously been reported in patients with lung injury and found to predict poorer outcomes.36–38 Additionally, OSA with its intermittent hypoxia and reoxygenation is thought to represent a state akin to chronic ischemia-reperfusion with increased ROS formation during restoration of oxygenation29; pro-inflammatory cytokine profile observed in OSA has been consistent with response to oxidative stress.39 OSA is also characterized by increased leptin levels with correlation found not only for BMI but also for apneahypopnea index and reduced adiponectin levels.40–42

Overall, it appears that there is a significant overlap between effects of obesity and OSA; and short of a prospective trial thoroughly screening for OSA on admission and then examining ARDS incidence across body weight categories and OSA severity while taking into account other confounding factors, it would be difficult to separate relative contributions of each.

Our study has several important limitations. Although a secondary analysis, it was pre-planned at the time of conception of the LIPS investigation. OSA was most likely underdiagnosed in our study population, as we relied only upon the information available at the time of hospital admission, thereby limiting potential inferences of its effect on studied outcomes. Additionally, we did not have data on OSA severity and compliance with CPAP therapy and therefore cannot separate the effect of treated and untreated OSA. This is important because CPAP therapy could negate the potential risk inherent in OSA and protect against ARDS. For those reasons and given a preponderance of obese OSA individuals in our cohort we separately examined the effect of BMI on ARDS and assessed the role of different BMI categories. Nonetheless, this study adds to the limited body of research into the role of OSA on the likelihood of developing ARDS. The strengths of the study include its multi-centered design and a large number of patients at risk for ARDS. Additionally, all patients in the cohort were systematically characterized as having or not having OSA specifically at admission, and followed subsequently for the development of ARDS. Given the potential overlap in mechanisms of lung effects with obesity, our study emphasizes the need to improve OSA screening in future ARDS prevention trials because in order to truly define the role of OSA, one needs to ensure that it is adequately ascertained as well as characterized (severity, compliance) among study participants.

CONCLUSIONS

Prior diagnosis of OSA did not affect development of ARDS among patients with at least one predisposing condition, nor did it affect the need for mechanical ventilation or hospital mortality. However, obesity appeared to independently increase the risk of ARDS.

DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

This was not an industry supported study. The study was supported in part by: KL2 RR024151 and the Mayo Clinic Critical Care Research Committee. The authors have indicated no financial conflicts of interest.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

USCIITG LIPS1 participating centers and corresponding investigators

Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minnesota: Adil Ahmed MD; Ognjen Gajic MD; Michael Malinchoc MS; Daryl J Kor MD; Bekele Afessa MD; Rodrigo Cartin-Ceba MD; Departments of Internal Medicine, Pulmonary and Critical Care Medicine, Health Sciences Research, and Anesthesiology

University of Missouri, Columbia: Ousama Dabbagh MD, MSPH, Associate Professor of clinical medicine; Nivedita Nagam MD; Shilpa Patel MD; Ammar Karo and Brian Hess

University of Michigan, Ann Arbor: Pauline K. Park, MD, FACS, FCCS, Co-Director, Surgical Intensive Care Unit, Associate Professor, Surgery; Julie Harris, Clinical Research Coordinator; Lena Napolitano MD; Krishnan Raghavendran MBBS; Robert C. Hyzy MD; James Blum MD; Christy Dean

University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center in Dallas, Texas: Adebola Adesanya MD; Srikanth Hosur MD; Victor Enoh MD; Department of Anesthesiology, Division of Critical Care Medicine

University of Medicine and Dentistry of New Jersey: Steven Y. Chang PhD, MD, Assistant Professor, MICU Director, Pulmonary and Critical Care Medicine; Amee Patrawalla MD, MPH; Marie Elie MD

Brigham and Women's Hospital: Peter C. Hou MD; Jonathan M. Barry BA; Ian Shempp BS; Atul Malhotra MD; Gyorgy Frendl MD, PhD; Departments of Emergency Medicine, Surgery, Internal Medicine and Anesthesiology Perioperative and Pain Medicine, Division of Burn, Trauma, and Surgical Critical Care

Wright State University Boonshoft School of Medicine & Miami Valley Hospital: Harry Anderson III MD, Professor of Surgery; Kathryn Tchorz MD, Associate Professor of Surgery; Mary C. McCarthy MD, Professor of Surgery; David Uddin PhD, DABCC, CIP, Director of Research

Wake Forest University Health Sciences, Winston-Salem, NC: James Jason Hoth MD, Assistant Professor of Surgery; Barbara Yoza PhD, Study Coordinator

University of Pennsylvania: Mark Mikkelsen MD, MSCE, Assistant Professor of Medicine, Pulmonary, Allergy and Critical Care Division; Jason D. Christie MD; David F. Gaieski MD; Paul Lanken MD; Nuala Meyer MD; Chirag Shah MD Temple University School of Medicine: Nina T. Gentile MD, Associate Professor and Director, Clinical Research; Karen Stevenson MD; Brent Freeman BS, Research Coordinator; Sujatha Srinivasan MD; Department of Emergency Medicine

Mount Sinai School of Medicine: Michelle Ng Gong MD, MS, Assistant Professor, Pulmonary, Critical Care and Sleep Medicine, Department of Medicine

Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Boston, Massachusetts: Daniel Talmor MD, Director of Anesthesia and Critical Care, Associate Professor of Anesthesia, Harvard Medical School; Stephen Patrick Bender MD; Mauricio Garcia MD

Massachusetts General Hospital Harvard Medical School: Ednan Bajwa MD, MPH, Instructor in Medicine; Atul Malhotra MD, Assistant Professor; Boyd Taylor Thompson MD, Associate Professor; David C. Christiani MD, MPH, Professor

University of Washington, Harborview: Timothy R. Watkins MD, Acting Instructor, Department of Medicine, Division of Pulmonary and Critical Care Medicine; Steven Deem MD; Miriam Treggiari MD, MPH

Mayo Clinic Jacksonville: Emir Festic MD; Augustine Lee MD; John Daniels MD Akdeniz University, Antalyia, Turkey: Melike Cengiz MD, PhD; Murat Yilmaz MD Uludag University, Bursa, Turkey: Remzi Iscimen MD Bridgeport Hospital Yale New Haven Health: David Kaufman MD, Section Chief, Pulmonary, Critical Care & Sleep Medicine, Medical Director, Respiratory Therapy

Emory University: Annette Esper MD; Greg Martin MD University of Illinois at Chicago: Ruxana Sadikot MD, MRCP University of Colorado: Ivor Douglas MD Johns Hopkins University: Jonathan Sevransky MD, MHS, Assistant Professor of Medicine, Medical Director, JHBMC MICU

The authors acknowledge the help and support of Rob Taylor (Vanderbilt University, Nashville, TX) and Joseph J Wick (Mayo Clinic) for the availability and maintenance of REDcap database.

REFERENCES

- 1.Pierrakos C, Vincent JL. The changing pattern of acute respiratory distress syndrome over time: a comparison of two periods. Eur Respir J. 2012;40:589–95. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00130511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Villar J, Blanco J, Añón JM, et al. ALIEN Network. The ALIEN study: incidence and outcome of acute respiratory distress syndrome in the era of lung protective ventilation. Intensive Care Med. 2011;37:1932–41. doi: 10.1007/s00134-011-2380-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gajic O, Dabbagh O, Park PK, et al. U.S. Critical Illness and Injury Trials Group. Lung Injury Prevention Study Investigators (USCIITG-LIPS). Early identification of patients at risk of acute lung injury: evaluation of lung injury prediction score in a multicenter cohort study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2011;183:462–70. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201004-0549OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gong MN, Bajwa EK, Thompson BT, Christiani DC. Body mass index is associated with the development of acute respiratory distress syndrome. Thorax. 2010;65:44–50. doi: 10.1136/thx.2009.117572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Punjabi NM. The epidemiology of adult obstructive sleep apnea. Proc Am Thorac Soc. 2008;5:136–43. doi: 10.1513/pats.200709-155MG. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Young T, Palta M, Dempsey J, Skatrud J, Weber S, Badr S. The occurrence of sleep-disordered breathing among middle-aged adults. N Engl J Med. 1993;328:1230–5. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199304293281704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Finkel KJ, Searleman AC, Tymkew H, et al. Prevalence of undiagnosed obstructive sleep apnea among adult surgical patients in an academic medical center. Sleep Med. 2009;10:753–8. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2008.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Memtsoudis S, Liu SS, Ma Y, Chiu YL, Walz JM, Gaber-Baylis LK, Mazumdar M. Perioperative pulmonary outcomes in patients with sleep apnea after noncardiac surgery. Anesth Analg. 2011;112:113–21. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0b013e3182009abf. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kaw R, Chung F, Pasupuleti V, Mehta J, Gay PC, Hernandez AV. Meta-analysis of the association between obstructive sleep apnoea and postoperative outcome. Br J Anaesth. 2012;109:897–906. doi: 10.1093/bja/aes308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Burke AJ, Duke SG, Clyne S, Khoury SA, Chiles C, Matthews BL. Incidence of pulmonary edema after tracheotomy for obstructive sleep apnea. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2001;125:319–23. doi: 10.1067/mhn.2001.117713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hwang D, Shakir N, Limann B, et al. Association of sleep-disordered breathing with postoperative complications. Chest. 2008;133:1128–34. doi: 10.1378/chest.07-1488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gali B, Whalen FX, Schroeder DR, Gay PC, Plevak DJ. Identification of patients at risk for postoperative respiratory complications using a preoperative obstructive sleep apnea screening tool and postanesthesia care assessment. Anesthesiology. 2009;110:869–77. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e31819b5d70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Weingarten TN, Flores SA, McKenzie JA, et al. Obstructive sleep apnoea and perioperative complications in bariatric patients. Br J Anaesth. 2011;106:131–39. doi: 10.1093/bja/aeq290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kaw R, Pasupuleti V, Walker E, Ramaswamy A, Foldvary-Schafer N. Postoperative complications in patients with obstructive sleep apnea. Chest. 2012;141:436–41. doi: 10.1378/chest.11-0283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Liu SS, Chisholm MF, Ngeow J, John RS, Shaw P, Ma Y, Memtsoudis SG. Postoperative hypoxemia in orthopedic patients with obstructive sleep apnea. HSS J. 2011;7:2–8. doi: 10.1007/s11420-010-9165-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Liao P, Yegneswaran B, Vairavanathan S, Zilberman P, Chung F. Postoperative complications in patients with obstructive sleep apnea: a retrospective matched cohort study. Can J Anaesth. 2009;56:819–28. doi: 10.1007/s12630-009-9190-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Blake DW, Chia PH, Donnan G, Williams DL. Preoperative assessment for obstructive sleep apnoea and the prediction of postoperative respiratory obstruction and hypoxaemia. Anaesth Intensive Care. 2008;36:379–84. doi: 10.1177/0310057X0803600309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lopes Neto JM, Brandão LO, Loli A, Leite CV, Weber SA. Evaluation of obstructive sleep apnea in obese patients scheduled for bariactric surgery. Acta Cir Bras. 2013;28:317–22. doi: 10.1590/s0102-86502013000400012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fuller BM, Mohr NM, Dettmer M, et al. Mechanical ventilation and acute lung injury in emergency department patients with severe sepsis and septic shock: an observational study. Acad Emerg Med. 2013;20:659–69. doi: 10.1111/acem.12167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Memtsoudis SG, Bombardieri AM, Ma Y, Walz JM, Chiu YL, Mazumdar M. Mortality of patients with respiratory insufficiency and adult respiratory distress syndrome after surgery: the obesity paradox. J Intensive Care Med. 2012;27:306–11. doi: 10.1177/0885066611411410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bernard GR, Artigas A, Brigham KL, et al. The American-European Consensus Conference on ARDS. Definitions, mechanisms, relevant outcomes, and clinical trial coordination. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1994;149:818–24. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.149.3.7509706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.ARDS Definition Task Force. Ranieri VM, Rubenfeld GD, Thompson BT, et al. Acute respiratory distress syndrome: the Berlin Definition. JAMA. 2012;307:2526–33. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.5669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Liao P, Kobah S, Wijeysundera DN, Shapiro C, Chung F. Proportion of surgical patients with undiagnosed obstructive sleep apnoea. Br J Anaesth. 2013;110:629–36. doi: 10.1093/bja/aes465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Simpson L, Hillman DR, Cooper MN, et al. High prevalence of undiagnosed obstructive sleep apnoea in the general population and methods for screening for representative controls. Sleep Breath. 2012;17:967–73. doi: 10.1007/s11325-012-0785-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Peppard PE, Young T, Barnet JH, Palta M, Hagen EW, Hla KM. Increased prevalence of sleep-disordered breathing in adults. Am J Epidemiol. 2013;177:1006–14. doi: 10.1093/aje/kws342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tuomilehto H, Seppä J, Uusitupa M. Obesity and obstructive sleep apnea--clinical significance of weight loss. Sleep Med Rev. 2013;17:321–9. doi: 10.1016/j.smrv.2012.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bellmeyer A, Martino JM, Chandel NS, Scott Budinger GR, Dean DA, Mutlu GM. Leptin resistance protects mice from hyperoxia-induced acute lung injury. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2007;175:587–94. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200603-312OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hibbert K, Rice M, Malhotra A. Obesity and ARDS. Chest. 2012;142:785–90. doi: 10.1378/chest.12-0117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Arnardottir ES, Mackiewicz M, Gislason T, Teff KL, Pack AI. Molecular signatures of obstructive sleep apnea in adults: a review and perspective. Sleep. 2009;32:447–70. doi: 10.1093/sleep/32.4.447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Keaney JF, Jr, Larson MG, Vasan RS, et al. Framingham Study. Obesity and systemic oxidative stress: clinical correlates of oxidative stress in the Framingham Study. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2003;23:434–9. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000058402.34138.11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lettieri CJ, Eliasson AH, Andrada T, Khramtsov A, Raphaelson M, Kristo DA. Obstructive sleep apnea syndrome: are we missing an at-risk population? J Clin Sleep Med. 2005;1:381–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Testelmans D, Tamisier R, Barone-Rochette G, Baguet JP, Roux-Lombard P, Pépin JL, Lévy P. Profile of circulating cytokines: Impact of OSA, obesity and acute cardiovascular events. Cytokine. 2013;62:210–6. doi: 10.1016/j.cyto.2013.02.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Agrawal A, Matthay MA, Kangelaris KN, et al. Plasma angiopoietin-2 predicts the onset of acute lung injury in critically ill patients. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2013;187:736–42. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201208-1460OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Aihara K, Oga T, Harada Y, et al. Comparison of biomarkers of subclinical lung injury in obstructive sleep apnea. Respir Med. 2011;105:939–45. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2011.02.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lederer DJ, Jelic S, Basner RC, Ishizaka A, Bhattacharya J. Circulating KL-6, a biomarker of lung injury, in obstructive sleep apnoea. Eur Respir J. 2009;33:793–6. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00150708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kondo T, Hattori N, Ishikawa N, et al. KL-6 concentration in pulmonary epithelial lining fluid is a useful prognostic indicator in patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome. Respir Res. 2011;12:32. doi: 10.1186/1465-9921-12-32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Determann RM, Royakkers AA, Haitsma JJ, Zhang H, Slutsky AS, Ranieri VM, Schultz MJ. Plasma levels of surfactant protein D and KL-6 for evaluation of lung injury in critically ill mechanically ventilated patients. BMC Pulm Med. 2010;10:6. doi: 10.1186/1471-2466-10-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sato H, Callister ME, Mumby S, Quinlan GJ, Welsh KI, duBois RM, Evans TW. KL-6 levels are elevated in plasma from patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome. Eur Respir J. 2004;23:142–5. doi: 10.1183/09031936.03.00070303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kimoff RJ, Hamid Q, Divangahi M, et al. Increased upper airway cytokines and oxidative stress in severe obstructive sleep apnoea. Eur Respir J. 2011;38:89–97. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00048610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zirlik S, Hauck T, Fuchs FS, Neurath MF, Konturek PC, Harsch IA. Leptin, obestatin and apelin levels in patients with obstructive sleep apnoea syndrome. Med Sci Monit. 2011;17:CR159–64. doi: 10.12659/MSM.881450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kelly A, Dougherty S, Cucchiara A, Marcus CL, Brooks LJ. Catecholamines, adiponectin, and insulin resistance as measured by HOMA in children with obstructive sleep apnea. Sleep. 2010;33:1185–91. doi: 10.1093/sleep/33.9.1185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kim J, Lee CH, Park CS, Kim BG, Kim SW, Cho JH. Plasma levels of MCP-1 and adiponectin in obstructive sleep apnea syndrome. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2010;136:896–9. doi: 10.1001/archoto.2010.142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]