Most Americans are familiar with seeing prescription drugs advertised on television, but few realize how direct-to-consumer (DTC) advertising has become so widespread. In 1997, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration relaxed its interpretation of the agency’s advertising regulations, which made it more feasible for manufacturers to broadcast prescription drug advertisements legally.1 Nearly two decades later, researchers are still seeking answers to critical questions about the impact of this policy change on the public health.

FDA Statutes and Regulation of Direct-to-consumer Advertising

Under FDA law, prescription drug advertisements must not be “false or misleading” and must also include information in “brief summary” about a drug’s side effects, contraindications, and effectiveness.1 For broadcast advertisements, which have more inherent limitations than written advertisements in communicating information, the FDA regulations allow the brief summary requirement to be satisfied through “adequate provision” of the approved prescription drug labeling to consumers, as long as information about the drug’s major risks are included in the advertisement.1

Few DTC ads were broadcast for prescription drugs in the 1980’s under this regulatory standard because of the difficulty in providing the drug labeling to consumers.2 Dr. David Kessler, who was FDA Commissioner between 1990 and 1997, opposed changing the agency’s policy to allow for more DTC ads.3 After Dr. Kessler departed the agency in January 1997, FDA leadership supported such a change in the form of a “draft guidance” issued just 6 months later.1 By clarifying the ways that companies could adequately provide the approved drug labeling to consumers, such as through website addresses highlighted in the broadcast advertisement, the guidance made it easier for manufacturers to legally broadcast these advertisements.1 This simple pronouncement has resulted in a major change in the marketing and promotion of prescription drugs.

DTC broadcast advertisements surged quickly in the marketplace shortly after the policy announcement. According to one estimate, televised advertisements peaked at 3.3 billion dollars in spending in 2006,4 but declined to 2.4 billion in 2010 during the recession.5 DTC advertisements comprised approximately 13% of total promotional spending in 2012, including print advertisements, detailing, and drug samples.5 DTC advertising has been highly concentrated within a small number of products, with many having relatively broad indications for use.4

DTC advertising for prescription drugs is legal only in the United States and New Zealand, and remains a lightning rod for controversy, with both vocal advocates and opponents.6 Studies have found that DTC advertising is associated with increases in prescription drug sales.7 Critics emphasize that consumers do not have sufficient medical knowledge to assess these advertising messages and that commercially-motivated messages lead to inappropriate prescribing by physicians, who face increasingly strong patient demands for medicines.4 Supporters, though, believe this advertising can empower consumers for their medical care and increase treatment for diseases.4

Assessments of Impact of Direct-to-consumer Advertising

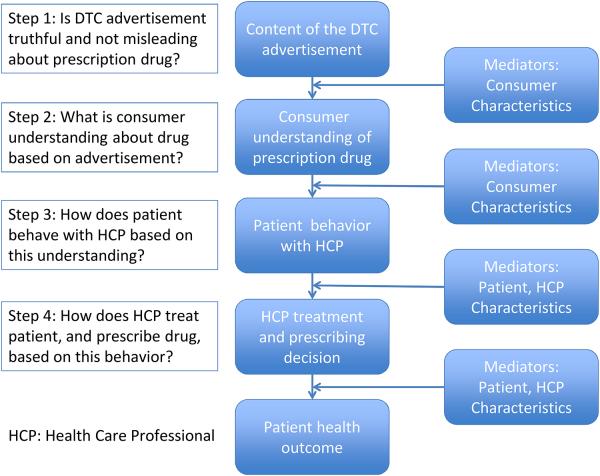

To assess DTC advertising’s effect on patients and health care professionals, it is important to consider the multiple steps between the viewing of an advertisement and patient outcomes (Figure 1). This pathway begins with the advertisement’s content. FDA is responsible for ensuring this content is not false or misleading, but advertisements are generally not submitted to FDA for pre-approval.8 FDA’s oversight responsibilities are overwhelming given the numerous DTC advertisements introduced in the marketplace each year. In addition, even advertisements that are technically truthful can still potentially mislead consumers regarding important drug information.8,9

Figure 1.

Steps Between Direct-to-consumer Advertisement Exposure and Patient Outcomes.

The second step is how consumers interpret and understand this advertisement content. FDA surveys of physicians and consumers have suggested that DTC advertisements have increased patient awareness of available treatments, but also confused patients about a drug’s relative risks and benefits.10 FDA is currently updating this survey evidence, and more recently completed FDA studies have identified factors, such as quantitative information, that can improve consumer understanding of a drug’s risks and benefits.11

The third step is how consumers act based on their understanding of the advertising content, particularly when interacting with their health care professional. FDA surveys have found that DTC advertisements have helped patients ask thoughtful questions during physician visits11 but other evidence is mixed about whether this advertising improves patient-physician interactions.6 In addition, other surveys have indicated that DTC advertising results in numerous patients seeking specific prescription drug treatments, many of which are inappropriate for their condition.6

The fourth step is how the health care professional treats the patient based on this interaction, and whether the professional prescribes advertised medication that may be discussed. Some evidence suggests that physicians may feel pressure to prescribe prescription drugs in response to direct patient requests11, and surveys have indicated changes in physician prescribing based on these requests.6 Only one experimental study (a community based randomized trial) has been conducted to rigorously assess the impact of patient medication requests on clinical practice; the investigators found that patient requests for antidepressants based on DTC advertisement had a profound effect on physician prescribing, suggesting that such ads may have competing effects on quality by decreasing underuse while simultaneously promoting overuse.12 The role of patient and provider characteristics must also be considered in evaluating the pathway of events depicted in Figure 1. For example, patient’s attitudes toward DTC advertising may influence the likelihood of patients’ medication requests and physicians’ prescribing decisions.13

New Experimental Study on Patient Requests for Prescription Drugs

The study by McKinlay and colleagues provides important information regarding how patient requests may impact provider practice. The authors used a factorial experimental design by randomizing 192 primary care physicians from 6 states to clinical scenarios depicting patients with symptoms of sciatica or chronic osteoarthritis. Each scenario had two patient versions - either an active request for a specific medication or passive request for pain relief. One in five physicians reported they would prescribe oxycodone for the sciatica patient requesting the drug, as compared to just 1% of physicians viewing the same clinical scenario with a patient who made a passive request for pain relief. More than half (53%) of physicians reported they would prescribe Celebrex to those patients with diagnosed osteoarthritis requesting the drug, while only one in four reported they would prescribe the drug for patients making a passive request for pain relief. These differences are not just statistically significant, but clinically significant as well. No patient or provider characteristics that the authors examined affected physicians’ willingness to prescribe medication, although certain practice characteristics did influence this tendency (e.g., physicians with income dependent on measures of care were more likely to recommend use of a prescription treatment).

These findings are important because the study addresses a non-trivial gap in our knowledge of how patient-physician interactions impact prescribing decisions, and the use of an experimental design allowed for estimations of the effect of patient requests unconfounded by patient, physician or practice characteristics. The study builds on prior research by showing that patient medication requests can increase prescribing for specific drugs. While the authors acknowledge that the use of oxycodone or celecoxib in these scenarios was “clinically plausible”, in both cases there were a variety of arguably safer or more cost-effective alternative pharmacologic and non-pharmacologic treatment options that might have been pursued. This effect of patients’ request was particular noteworthy in the case of oxycodone, given an epidemic of opioid-related morbidity and mortality in the United States.14

The study has important limitations, such as the purposive recruitment of physicians, which limits generalizability, and the lack of sequence randomization for the scenarios, which raises concerns that physician responses might have been affected by the patient order. Also, despite the thorough approach in developing the video presentations, and some evidence suggesting the clinical fidelity of hypothetical vignettes15, it remains unclear how the physicians sampled would have reacted with actual patients. It might also have been helpful for the authors to have tested other scenarios where the requested drug would have been the most appropriate treatment option – to evaluate the degree to which such requests can contribute to better prescribing decisions. Despite these issues, the study provides important knowledge about how patient medication requests can shape physician prescribing.

Next Steps for DTC Advertising Research and Regulation

McKinlay et. al’s research must be used to inform regulatory policy. William Schultz, then FDA Deputy Commissioner for Policy, made clear at a 1995 public meeting about DTC advertising that in the United States “there is a presumption that is in favor of the free flow of information” and that “any agency that is trying to stop that has a burden to carry to explain why and what the interests are.”16 Under this view of the agency’s regulatory burden, FDA justified the 1997 policy by emphasizing the lack of evidence about DTC advertising’s negative effects, rather than identifying any scientific evidence showing positive effects.17 This presumed burden on FDA to show negative effects from DTC advertising, grounded in constitutional principles for commercial free speech, is starkly contrasted to each manufacturer’s burden to demonstrate a prescription drug’s safety and effectiveness through well-controlled clinical trials.

Despite the best efforts of academic and FDA researchers to investigate these questions in the face of serious budget constraints, we have very little experimental evidence today that assesses the effect of current DTC marketing on patient and prescribing behavior, particularly health outcomes. The authors’ helpful investigation is a critical step in this process, but more research is needed.

Pharmaceutical manufacturers must also assume more responsibility for the public health outcomes from their advertisements. In fact, FDA has asked drug companies to make their research about the effect of DTC advertising on public health available in the public domain1, but companies have not heeded this request. It seems only fair that if manufacturers can profit from DTC advertising, they should also share the results of the studies upon which they rely to justify these marketing campaigns as part of their business model. Only through these steps can we understand more clearly the myriad effects from DTC advertising, which in turn can help to optimize regulatory oversight for public health protection.

Acknowledgments

Support

Dr. Alexander is supported by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (RO1 HS0189960) and the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute (R01 HL107345). Mr. Fain is supported as a Sommer Scholar at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health. The funding sources had no role in the design and conduct of the study, analysis, or interpretation of the data and preparation or final approval of the manuscript prior to publication.

Footnotes

Disclosures

Mr. Fain worked in the Office of Chief Counsel at the U.S. Food and Drug Administration from 1995 until 2010.Dr. Alexander is an ad hoc member of the FDA’s Drug Safety and Risk Management Advisory Committee, serves as a paid consultant to IMS Health and serves on an IMS Health scientific advisory board. This arrangement has been reviewed and approved by Johns Hopkins University in accordance with its conflict of interest policies.

References

- 1.US Food and Drug Administration Draft Guidance for Industry: Consumer-Directed Broadcast Advertisements. 1997 Aug 12; Notice of Availability. Available at http://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/FR-1997-08-12/pdf/97-21291.pdf. Accessed February 8, 2014.

- 2.U.S. Food and Drug Administration Notice of public hearing; request for comments. 1995 Aug 16; Available at http://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/FR-1995-08-16/pdf/95-20314.pdf. Accessed on February 8, 2014.

- 3.The New York Times Stuart Eliot. The media business: advertising; a seminar examines the plethora of prescription drug pitches since regulations were loosened. 1998 Jun 15; Available at http://www.nytimes.com/1998/06/15/business/media-business-advertising-seminar-examines-plethora-prescription-drug-pitches.html. Accessed February 8, 2014.

- 4.Kornfield R, Donohue J, Berndt ER, Alexander GC. Promotion of prescription drugs to consumers and providers, 2001-2010. PLOS One. 2013;8(3):e55504. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0055504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.The Pew Charitable Trusts Persuading the Prescribers: Pharmaceutical Industry Marketing and its Influence on Physicians and Patients. 2013 Nov 11; Available at http://www.pewhealth.org/other-resource/persuading-the-prescribers-pharmaceutical-industry-marketing-and-its-influence-on-physicians-and-patients-85899439814. Accessed February 8, 2014.

- 6.Frosch DL, Grande D, Tarn DM, Kravitz RL. A decade of controversy: balancing policy with evidence in the regulation of prescription drug advertising. Am J Public Health. 2010;100(1):24–32. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2008.153767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gilbody S, Wilson P, Watt I. Benefits and harms of direct to consumer advertising: a systematic review. Qual Saf Health Care. 2005;14:246–250. doi: 10.1136/qshc.2004.012781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Frosch DL, Krueger PM, Hornik RC, Cronbolm PF, Barg FK. Creating demand for prescription drugs: a content analysis of television direct-to-consumer advertising. Ann Fam Med. 2007;5(1):6–13. doi: 10.1370/afm.611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Faerber AE, Kreling DH. Content Analysis of False and Misleading Claims in Television Advertising for Prescription and Nonprescription Drugs. J Gen Intern Med. 2013;29(1):110–118. doi: 10.1007/s11606-013-2604-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.US Food and Drug Administration The Impact of Direct-to-Consumer Advertising. 2014 Feb 8; Available at http://www.fda.gov/Drugs/ResourcesForYou/Consumers/ucm143562.htm. Accessed.

- 11.US Food and Drug Administration Office of Prescription Drug Promotion (OPDP) Research. 2014 Feb 8; Available at http://www.fda.gov/AboutFDA/CentersOffices/OfficeofMedicalProductsandTobacco/CDER/ucm090276.htm. Accessed.

- 12.Kravitz RL, Epstein R, Feldman MD, Franz CE, Azari R, Wilkes MS, Hinton L, Franks P. Influence of patients’ requests for directly advertised antidepressants: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2005;293(16):1995–2002. doi: 10.1001/jama.293.16.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Herzenstein M, Misra S, Posavac SS. How consumers’ attitudes toward direct-to-consumer advertising of prescription drugs influence ad effectiveness, and consumer and physician behavior. Marketing Letters. 2004;15(4):201–212. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Alexander GC, Kruszewski SP, Webster DW. Rethinking Opioid Prescribing to Protect Patient Safety and Public Health. JAMA. 2012;308:1865–1866. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.14282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Peabody JW, Luck J, Glassman P, Dresselhaus TR, Lee M. Comparison of Vignettes, Standardized Patients, and Chart Abstraction: A Prospective Validation Study of 3 Methods for Measuring Quality. JAMA. 2000;283:1715–1722. doi: 10.1001/jama.283.13.1715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.US Food and Drug Administration Transcript of Direct-to-Consumer Promotion Public Hearing–Introduction. 1995 Oct 18; Available at http://www.fda.gov/aboutfda/centersoffices/officeofmedicalproductsandtobacco/cder/ucm092224.htm. Accessed February 8, 2014.

- 17.US Food and Drug Administration Guidance for Industry. Consumer-Directed Broadcast Advertisements. Questions and Answers. 1999 Aug; Available at http://www.fda.gov/downloads/Drugs/GuidanceComplianceRegulatoryInformation/Guidances/ucm122825.pdf. Accessed February 8, 2014.