Abstract

Advances in nanotechnology and chemical engineering have led to the development of many different drug delivery systems. These 1-100(0) nm-sized carrier materials aim to increase drug concentrations at the pathological site, while avoiding their accumulation in healthy non-target tissues, thereby improving the balance between the efficacy and the toxicity of systemic (chemo-) therapeutic interventions. An important advantage of such nanocarrier materials is the ease of incorporating both diagnostic and therapeutic entities within a single formulation, enabling them to be used for theranostic purposes. We here describe the basic principles of using nanomaterials for targeting therapeutic and diagnostic agents to pathological sites, and we discuss how nanotheranostics and image-guided drug delivery can be used to personalize nanomedicine treatments.

Keywords: Nanomedicine, Drug targeting, Theranostics, Image-guided drug delivery, Personalized medicine

1. Introduction

Cancer is a highly complex disease, characterized by more than ten severely deregulated pathological hallmarks, including e.g. cellular proliferation, angiogenesis, inflammation, infiltration and metastasis [1,2]. There are numerous different types of cancer, varying from gender-specific malignancies, such as breast or prostate cancer, which actually are the most common cancer types in the respective gender, to lung and colon cancer, which are common in both sexes (www.cancer.gov). Every organ of the human biological system can be affected by cancer. The cause of cancer is even more complex than the different types of cancer. It ranges from genetic predisposition, e.g. mutation of the APC gene in colon cancer, to mutations induced by environmental factors, such as cigarette smoke in lung cancer and UV-light in skin cancer, to chronic inflammation, e.g. inflammatory bowel disease in colon cancer [3-5]. These insights show that there are many diverse mechanisms underlying the many types of cancer. This heterogeneity in cancer localization, cause, initiation and progression results in very distinct characteristics of tumors. Personalized medicine tries to identify such characteristics, and to develop therapies which are tailored and optimized for the treatment of individual patients and tumors.

In general, cancer therapy is primarily based on (combinations of) surgery, radiotherapy and chemotherapy. Based on tumor type and tumor stage, specific monotherapies or combination treatments are available. In numerous cases, these meticulously optimized therapy regimens are reasonably effective, but in many other cases they almost completely fail. These failures are most obvious in the case of metastatic disease, as radiotherapy and surgery are then no longer able to provide realistic prospects for long-term curative treatment. In such cases, chemotherapeutic drugs are needed to try to systemically treat the disease.

Systemic chemotherapy, however, is associated with serious drawbacks, such as inadequate bioavailability of the drug within the tumorous tissue, heterogeneous drug distribution at target site, high levels of off-target accumulation causing adverse effects, and the development of multi-drug resistance [6-9]. These limitations exemplify that even though tremendous efforts have been invested in developing novel, more effective and more specific chemotherapeutic drugs, a major hurdle for efficient cancer therapy remains to be the development of materials and methods to enable their site-specific delivery to tumors and tumor cells. In this regard, one should keep in mind that current chemotherapeutic cocktails are, in principle, very efficient in their mechanism of action, and if a sufficient amount of the agents would homogenously accumulate within tumors, they would likely be quite effective [10,11]. However, this ideal situation can often not be realized, as off-target site accumulation and toxicity severely limit the dosing regimen of low-molecular-weight (chemo-) therapeutic drugs.

To overcome these limitations, many different drug delivery systems have been designed and evaluated over the years. Examples of such drug delivery systems, which are more and more being used in the clinic, are liposomes, polymers, proteins, micelles and nanoparticles [8,12,13]. Besides therapeutics, also imaging agents can be incorporated into such nanocarrier materials, providing valuable diagnostic information. This enables them to be used as theranostic agents, which can be employed to non-invasively monitor drug delivery, drug release and drug efficacy, and which therefore hold significant potential for personalizing nanomedicine treatments [14,15]. In the present manuscript, we briefly describe the use of nanocarrier materials for drug delivery and imaging purposes, and we discuss how combining diagnostic and therapeutic properties within a single nanomedicine formulation can be used to individualize and improve (chemo-) therapeutic treatments.

2. Drug delivery systems

The development of drug delivery systems essentially started in the 1960s, and this still forms the basis for much of today’s research. The above-mentioned carrier materials, i.e. liposomes, polymers, proteins, micelles and nanoparticles, are the preclinically most extensively used and clinically most advanced drug delivery systems [13,16,17]. Besides assuring basic properties, such as high drug loading, stable drug retention and controlled drug release, the chemical functionalization of these materials can be performed for many different reasons, including e.g. active targeting, imaging and triggered release. As a result of this, ever more drug delivery systems and nanomedicine formulations are being developed. However, the design of ever more advanced formulations has several conceptual drawbacks, which not infrequently result in poor in vivo performance. This is often due to a lack of pharmacokinetic and/or (patho-) physiologic understanding of drug delivery processes, and could be overcome by more interdisciplinary cooperations between physicians and experts in chemistry, nanotechnology, material sciences, pharmacy, imaging and drug delivery. Not only the concept, but also the cost and the ability to upscale the synthesis procedure by pharmaceutical companies are important questions for clinical translatability. Taking this into account, ‘keep it simple’ generally is a good dogma, both for decent in vivo efficacy, and for clinical translation. The major advantage of nanomedicines is their altered bioavailability and pharmacokinetic behavior compared to free (chemo-) therapeutic drugs [14], thereby overcoming some of the problems and limitations of conventional anticancer agents. Ideal drug delivery systems provide high drug-loading densities, high tumor and minimal off-target localization, tipping the efficacy-to-toxicity balance (i.e. the therapeutic index) towards a more favorable direction.

Historically, the development of drug delivery systems started with the invention of hollow phospholipid bilayer materials by Bangham and colleagues in 1965, which were later termed liposomes, and which turned out to be suitable carriers for loading and delivering drugs [18-20]. From the late 1970s onwards, extensive research has led to optimized properties with respect to pharmacokinetic behavior, drug loading and drug release from liposomes. Today, about a dozen liposomal nanomedicines have been approved for clinical use or many others are in clinical trials [13,21]. Changing the lipid composition or incorporating cholesterol within the lipid bilayer can be used to optimize liposome stability, whereas surface modification via PEGylation can be performed to influence the pharmacokinetic behavior: functionalizing liposomes with small (2-5 kDa) and biocompatible PEG-based polymers significantly prolongs their circulation time [22,23]. This process, i.e. PEGylation, reduces protein adsorption (opsonisation) to liposomes, it reduces their clearance rates by the mononuclear phagocyte system (MPS) and it thereby prolongs their plasma half-life times. This beneficial pharmacokinetic behavior is of special interest for passive drug targeting to tumors, which is based on the enhanced permeability and retention (EPR) effect. The underlying rationale for using the EPR effect is based on the pathophysiological phenomenon that solid tumors tend to possess leaky blood vessels, and lack functional lymphatic drainage [24,25]. This results in a gradual accumulation of long circulating nanocarrier materials at the pathological site, while preventing their accumulation in healthy organs and tissues (as the latter generally present with an intact endothelial lining and with a fully functional lymphatic system).

Doxil, i.e. ~100 nm-sized PEGylated liposomes containing doxorubicin, is likely the most widely used nano-drug. [26]. Early studies convincingly showed that PEGylated liposomes extend the circulation half-life time of doxorubicin quite extensively, leading to increased tumor accumulation via EPR [27,23]. Since 1995, Doxil is approved for treating Kaposi sarcoma patients, and its approval was extended to ovarian and breast cancer in 1999 and 2003, respectively [13]. More sophisticated formulations, such thermosensitive liposomes, with a slightly modified lipid composition, undergo a phase transition upon heating above a defined temperature, resulting in controlled content release upon heating. ThermoDox® is a prototypic example of such a temperature-sensitive liposomal formulation, and is currently evaluated in different cancer types [28].

In addition to liposomes, also polymers have been extensively used for drug delivery purposes. In 1994, poly-(N-(2-hydroxypropyl)methacrylamide) (pHPMA) coupled to doxorubicin was the first so-called polymer therapeutic entering clinical trials [12,29]. In the years that followed, in addition to such linear macromolecular carrier materials, many other polymeric drug delivery systems have been designed and evaluated, including e.g. polymer-protein conjugates, dendrimers, polymeric micelles and polymeric nanoparticles [30,31]. A promising recent example in this regard refers to docetaxel incorporated into PSMA-targeted PLA nanoparticles: in very extensive preclinical and pioneering proof-of-principle clinical studies, Hrkach and colleagues demonstrated that these polymeric nanoparticles showed prolonged circulation times and improved anti-tumor activity compared to standard solvent-based docetaxel [32].

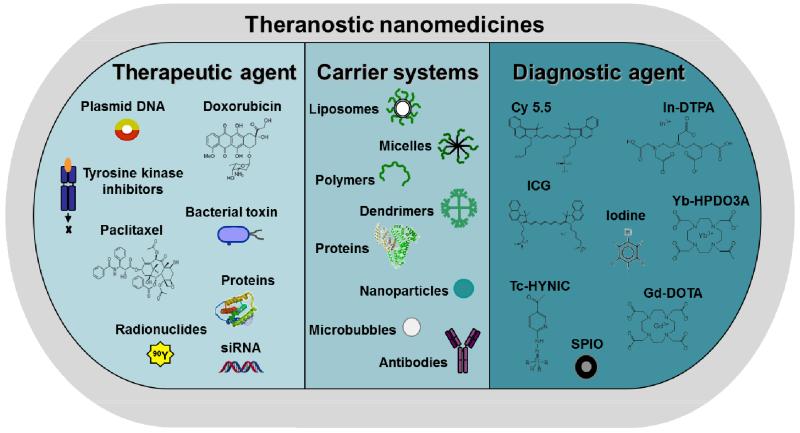

As depicted schematically in Figure 1, apart from polymers and liposomes, many other nanocarrier materials have been developed over the years. In addition, apart from standard chemotherapeutic drugs, such as doxorubicin and docetaxel, numerous other therapeutic agents have been incorporated. And furthermore, as addressed in more detail below (see sections 4-6), besides therapeutics, also imaging agents have been incorporated into nanocarrier materials, to enable functional and molecular imaging, image-guided drug delivery and personalized nanomedicine treatments.

Figure 1.

Schematic representation of carrier materials, therapeutic agents and imaging probes routinely used to prepare theranostic nanomedicine formulations.

3. Imaging

The implementation of imaging techniques for diagnostic purposes is one of the most fundamental procedures in medicine. It enables the non-invasive assessment of anatomical, functional and molecular information, which allows the diagnosis of (patho-) physiological abnormalities. The imaging modalities most often used in the clinic are computed tomography (CT), ultrasound (US), magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), positron emission tomography (PET) and single-photon emission computed tomography (SPECT). These modalities differ significantly with respect to underlying physical principles, and therefore have distinct advantages and disadvantages with regard to resolution, sensitivity and contrast [33]. Figure 2A provides a schematic overview of the different areas of medical imaging and their applications.

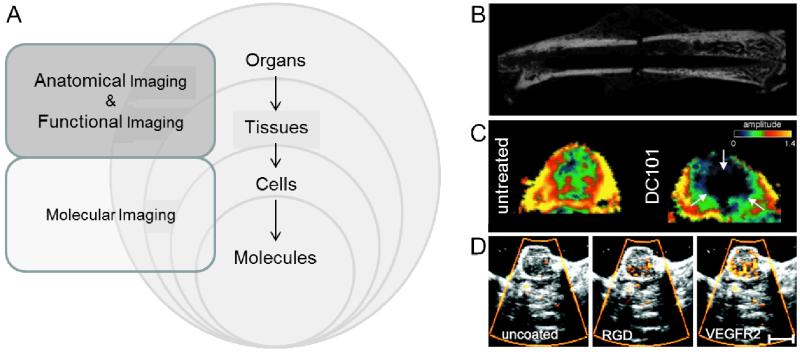

Figure 2.

Schematic overview of imaging levels in case of anatomical, functional and molecular imaging (A). Anatomical imaging of a fractured mouse femur (B). DCE-MRI of a non-treated or DC101-treated squamous cell carcinoma xenograft four days after therapy start (C). Molecular US imaging of control, RGD and VEGFR2 -coated microbubbles, showing specific binding of RGD and VEGFR2 microbubbles to angiogenic tumor blood vessels (D). Figure adapted from [45,46,37,43].

Anatomical imaging forms the basis for identifying and localizing morphological abnormalities. For that purpose, CT, US and MRI generally are the modalities of choice. Whereas the contrast CT is generated by differences in absorbance of X-rays in different tissues, US is based on sound echoes, where the difference of the acoustic impedance at a boundary is the determining factor of how much ultrasound waves will be reflected. MRI on the other hand relies on the magnetization properties of hydrogen atoms in the body. Due to their different (bio-) physical principles, these modalities differ significantly in their applicability and tissue contrast properties. US, for instance, is highly suitable for real-time imaging in prenatal care, as well as for the anatomical investigation of soft tissues, as it is a quick, cheap and easy method, has high resolution and causes no radiation effects. CT, on the other hand, does come with exposure to ionizing irradiation, but has the advantage of producing low-cost and user-independent images with high spatial resolution, making this technique highly suitable to detect e.g. skeletal defects (see Figure 2B). In contrast to CT, MRI offers high soft-tissue contrast, and is probably the most advanced and most versatile imaging technique. However, compared to the other modalities, it is relatively time- and cost-intensive.

Functional imaging aims to visualize physiological processes, rather than morphological structures. The same modalities as for anatomical imaging can be used for the acquisition of functional parameters. Power Doppler imaging, for blood flow analysis using ultrasound, as well as arterial spin labeling (ASL) and blood oxygenation level dependent (BOLD) imaging, for perfusion and hypoxia measurements using MRI, are techniques which do not require contrast agents. In most cases, however, contrast agents are required for functional imaging. For example, small gas-filled microbubbles can be used to generate vascular contrast in US. Thereby, physiological parameters such relative blood volume and perfusion can be visualized and quantified [34]. For CT, radiopaque contrast agents, mostly containing iodine or barium, are used. In addition to information on relative blood volume and perfusion, functional feedback on e.g. vascular permeability can be obtained using DCE-CT [35]. Similarly, dynamic MRI measurements, i.e. DCE-MRI, can be used to obtain functional information on e.g. (tumor) blood vessel perfusion and permeability [36]. Low-molecular-weight gadolinium-containing contrast agents, for instance, can be used to detect changes in the permeability constant kep and the amplitude A upon DC101-based anti-angiogenic therapy (Figure 2C) [37]. A comprehensive overview of vascular parameters that can be assessed using dynamic contrast-enhanced imaging techniques is provided in [38].

Molecular imaging arguably is the most advanced method for visualizing pathological processes. It is based on the imaging of cellular and molecular processes, such as metabolism, receptor expression and enzyme activity. In molecular imaging, contrast agents which are able to bind to (or to be metabolized in) specific target cells or tissues are employed. Considering contrast agent specificity, the imaging modalities used for molecular imaging have to be very sensitive, in order to detect very low amounts of contrast agent, and relatively subtle changes in receptor expression and/or enzyme activity. Due to its low contrast agent sensitivity, CT is not very useful for molecular imaging purposes. Similarly, also MRI suffers from relatively low contrast agent sensitivity and might therefore not be highly suitable for molecular imaging applications. Nonetheless, several contrast agents, such as antibody- or peptide-coated ultrasmall superparamagnetic iron oxide nanoparticles (USPIO) have been developed for molecular MR imaging purposes [39,40]. Much more suitable, at least for molecular imaging of vascular markers, is US. In particular in pre-clinical studies, antibody- or peptide-modified microbubbles have been quite extensively used to analyze tumor angiogenesis and/or the response to (anti-) vascular therapies [41,42]. In Figure 2D, representative images of molecular US are shown. In this case, the Sensitive Particle Acoustic Quantification (SPAQ) technique was used to assess anti-angiogenic therapy effects in squamous cell carcinoma xenografts by non-invasive measurement of VEGFR2 and αvβ3 integrin expression [43]. It was shown that longitudinal molecular US measurements can be used to assess vascular therapy effects in vivo. Clinical trials using similar microbubble-based contrast agents have recently been initiated for prostate cancer staging [44]. Apart from US, also nuclear medicine-based techniques, such as PET and SPECT, are highly suitable for molecular imaging purposes, as the radionuclide labeling of e.g. glucose and metabolic probes allows highly sensitive detection. A drawback of nuclear imaging techniques, however, is their lack of anatomical information, which can be resolved by turning to hybrid imaging techniques, such as PET-CT, PET-MRI and SPECT-CT.

4. Nanoparticles for imaging

Nanoparticles as contrast agents for (functional and molecular) imaging applications often include some of the potential drug delivery systems mentioned above, but also comprise additional nanoparticles, such as USPIO or gold nanoparticles, which can be used as contrast agents for MRI and CT, respectively. However, not every (nano-) imaging agent showing in vivo contrast is useful and suitable for clinical translation, in particular if the agent is given intravenously. Depending on the pathology or process to be imaged, the use of contrast agents, and in particular nanoparticulate contrast agents, often is not necessary [47]. This is because many diagnostic procedures in clinical routine can be performed without the use of contrast agents (e.g. angiography, using arterial spin labeling MRI), and also because 10-100 nm-sized diagnostics are inferior to both very small (<1 nm) or very large (>1 μm) agents when it comes to retrieving highly specific molecular imaging information [47]. Since diagnostic agents should ideally present strong specificity for the diseased site, low-molecular-weight (‘pico’) contrast agents, which are generally excreted very fast by renal clearance and thus have no (or at least very low) background, tend to be optimal for achieving high signal-to-noise ratios. The same holds true for very large (‘micro’) imaging agents, which do not extravasate, and which circulate for very short periods of time. Both very small and very large contrast agents furthermore tend to be devoid of pharmacological and/or toxicological effects. Intermediately sized, long circulating and slowly excreted (nano-) imaging agents, on the other hand, might cause both high background and long-term toxicity effects, and therefore really have to show distinct advantages to substitute classical small and large diagnostic probes in order to become really useful in the clinic. Therefore, especially for such intermediately sized materials, the assessment of toxicity in cells, animals and patients is highly important, and should be properly dealt with when intending to develop novel diagnostic or therapeutic nanoformulations. Some of the major challenges regarding toxicity in nanomedicine development are summarized in [48]. In contrast to the considerable amount of papers published on the use of nanoparticles for functional and molecular imaging, there are only a very few nanoparticle-based contrast agents and applications which really seem relevant from a clinical point of view. These e.g. include applications in which the long-circulating and/or poor renal clearance characteristics of such formulations are advantageous, as in case of monitoring of the mononuclear phagocytic system (MPS), in (stem) cell tracking and in implant imaging. For more details on such applications and on the use of nanoparticles for imaging purposes, the reader is referred to [47].

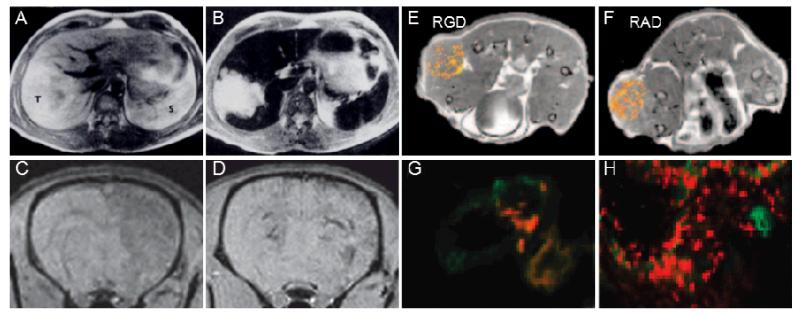

Three examples showing situations in which nanoparticles might be useful for (molecular) imaging applications are depicted in Figure 3. Polymer-coated SPIO nanoparticles, for instance, are known to be taken up quite efficiently by the MPS upon i.v. injection, causing a significant drop in the T2 signal in the liver [49,50]. This enables the detection of hepatic lesions, such as tumors, in which significantly less Kupffer cells are present as compared to healthy liver tissue (Figure 3A-B). Similar nanoparticles have been used to label cells for cell tracking purposes [51]. This ex vivo labeling method enables in vivo MRI-based monitoring of cell migration, e.g. into inflamed areas or into lymph nodes. Figures 3C-D exemplarily show MR images of rat brains, after the injection of SPIO labeled VLA-4-expressing human glial precursor (hGP) cells into the common carotid artery [52]. As VLA-4 is known to bind to VCAM-1 in inflamed brain endothelium, this study shows the potential of targeted cellular therapeutics to image brain abnormalities by real-time MRI guidance. Such concepts are highly useful to better understand the in vivo potential, function and migration of e.g. cancer cells, stem cells and immune cells [53]. These two studies are prototypic examples of functional imaging using nanoparticulate contrast agents.

Figure 3.

Nanoparticles as imaging agents. T2-weighted images of liver tumors before (A) and after (B) the i.v. injection of SPIO nanoparticles (tumor indicated by T, spleen by S). Strong negative contrast delineates the exact margins of the tumor. T2-weighted images of LPS-stimulated (C) or native (D) rat brains after the intra-arterial injection of SPIO-labeled VLA-4 expressing human glial precursor cells. Only in the stimulated rat (C), a negative contrast, corresponding to cell retention, is observed. MR images obtained 35 min after the i.v. injection of RGD-conjugated (E) vs. RAD-modified control liposomes (F) into tumor-bearing mice. The respective fluorescence images of the tumor are shown in (G) and (H). Figures adapted from [50,52,54].

When using nanoparticles for molecular imaging purposes, because of their prolonged circulation times and poor tissue penetration properties, choosing target receptors on blood vessels seems to be more beneficial than targeting receptors expressed by e.g. cancer cells. In this case, the long circulating properties of the nanoparticles are advantageous, as they increases the likelihood of vascular target binding, while avoiding the necessity for deep tumor and/or tissue penetration (which is severely hampered by nano-size; and completely blocked by micro-size). In this regard, many efforts have focused on the use of the small oligopeptide RGD, which is known to bind to αvβ3 integrins, which are highly expressed on activated (tumor) endothelium, and which can be used to assess angiogenesis. Mulder and colleagues have for instance developed bimodal gadolinium- and fluorophore-containing liposomes coated either with RGD (αvβ3 targeting) or RAD (control) peptides [54]. They imaged the in vivo accumulation and distribution of liposomes by MRI, and validated target-specific vascular binding of RGD- vs. RAD-targeted nanodiagnostics using ex vivo fluorescence microscopy (Figure 3G-H). In both cases, however, relatively high levels of liposome accumulation were observed in tumors. Fluorescence microscopy showed that the RGD-modified liposomes were primarily associated with tumor-associated blood vessels (Figure 3G), and MRI indicated that this happened mostly in the periphery of the tumors (Figure 3E). Interestingly, RAD-modified control liposomes accumulated in tumors at least equally efficiently, likely by means on non-target-receptor-specific EPR, but they appeared to be more homogenously distributed in the MR images (Figure 3F). This was confirmed using fluorescence microscopy, showing a much more widespread distribution throughout the tumor, and less colocalization with angiogenic blood vessels (Figure 3H). These insights show that targeted molecular imaging using nanoparticles is in principle possible, in particular in case of vascular targets, but that might not be as broadly applicable as generally assumed, because of the relatively high ‘non-specific’ accumulation of nanoparticles at pathological sites because of EPR.

5. Image-guided drug delivery

When combining diagnostic and therapeutic properties within a single nanoparticle formulation, the purpose of the incorporated imaging agent changes quite a bit. In this case, it is not being used anymore to obtain specific molecular imaging information on e.g. target receptor expression, but rather to trace the drug delivery system and/or the incorporated drug upon systemic administration. At the preclinical level, this can be done to assess the pharmacokinetics, the biodistribution and the target site accumulation of newly developed nanomedicine formulations, as well as to monitor (triggered) drug release. Such image-guided insights provide important non-invasive imaging information on the performance of drug delivery systems, and are considered to be highly useful for facilitating their in vivo performance and clinical translation.

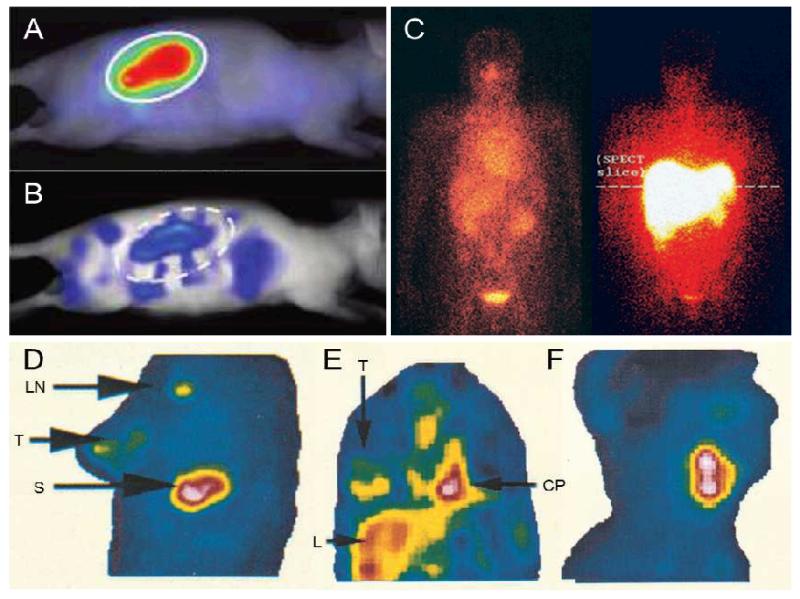

Figure 4 summarizes exemplary studies on image-guided drug delivery that have been performed over the years. Copolymers based on pHPMA, for instance, are known to have long circulation times and can therefore passively accumulate in tumors by means of EPR. This is representatively shown in Figure 4A-C using optical imaging and gamma-scintigraphy. Figure 4A and 4B e.g. show the EPR-mediated passive tumor accumulation of a near-infrared fluorophore-labeled polymer in subcutaneous CT26 tumors at 72 h post i.v. injection using 2D fluorescence reflectance imaging (FRI) and 3D fluorescence molecular tomography (FMT), respectively [55]. The left panel in Figure 4C, obtained at an early time point after i.v. injection of radiolabeled PK1 (i.e. pHPMA-GFLG-doxorubicin) in a human patient suffering from colorectal cancer, at which no EPR-mediated tumor accumulation has taken place yet, confirms the long circulation time of the polymer (strong signal in heart), as well as its partial renal excretion (strong signal in kidney and bladder). The right panel in Figure 4C depicts the biodistribution of a similar polymer conjugate targeted to the liver, using galactosamine as a hepatocyte-specific targeting moiety [56].

Figure 4.

Image-guided drug delivery. 2D fluorescence reflectance image (FRI; A) and 3D fluorescence molecular tomography (FMT; B) of a near-infrared fluorophore-labeled HPMA copolymer in mice bearing subcutaneous CT26 tumors. Gamma-scintigraphy of patients 24 h after the i.v. injection of radiolabeled PK1 (pHPMA-doxorubicin; left) and PK2 (galactosamine-targeted pHPMA-doxorubicin; right) (C). Gamma-camera images obtained at 72 h after the i.v. injection of indium-labeled PEGylated liposomes in breast cancer (D), lung cancer (E), and head-and-neck cancer (F). Images demonstrate accumulation in tumor (T), lymph node (LN), liver (L), spleen (S) and cardiac blood pool (CP). Figures adaped from [55,57,56].

Figures 4D-F refer to radiolabeled liposomes. As mentioned before, PEGylated liposomes circulate for prolonged periods of time, and therefore in principle are highly suitable for passive drug targeting to tumors. However, as elegantly demonstrated by Harrington and colleagues using indium-111-labeled PEGylated liposomes, not all tumors are equally amenable to EPR-mediated drug targeting [57]. Using non-invasive radionuclide imaging, they convincingly showed that the degree of tumor accumulation differed significantly in between different types of tumors. The lowest levels were found in breast carcinoma patients (5±3 %ID/kg), moderate uptake was observed in lung tumors (18±6 %ID/kg), and the highest levels of accumulation were found in head and neck carcinomas (33±16 %ID/kg) (Figure 4D-F). This indicates that the targeting and therapeutic efficacy of liposomal nanomedicines differs depending on tumor type.

However, not only the biodistribution and the target site accumulation of nanomedicines is of interest, but also drug release. This is because the drug must become bioavailable within the target tissue, in order to induce a therapeutic effect. Hence, more advanced liposomal formulations have been developed, in particular for temperature-triggered drug release. Such heat-sensitive liposomes disintegrate upon mild hyperthermia and then rapidly release their contents. ThermoDox® is an example of such an advanced liposomal formulation. Upon local hyperthermia, the lipids in the bilayer re-arrange to form drug-permeable pores, and the incorporated chemotherapeutic agent can then be released. Several preclinical studies, in which MR contrast agents have been co-incorporated with doxorubicin, have shown that temperature triggering leads to efficient heat-induced drug release, and a number clinical trials are currently ongoing to assess the potential of ThermoDox®, e.g. in case of metastatic liver cancer and recurrent chest wall breast cancer [28,58,59].

6. Theranostic concepts for personalized nanomedicine

Personalized medicine can be understood as a strategy to diagnose, treat and monitor diseases and disease treatments in ways that achieve individualized and improved health-care decisions. Based on this notion, and taking the large intra- and intertumoral heterogeneity into account, treatment plans need to be as versatile and adaptive as the tumors themselves. This requires the development of materials and methods to assess tumor and therapy characteristics in sufficient detail, and not only encompasses image-guided decision making with regard to classical vs. nanomedicine-based treatments, but also with regard to which of the available (standard and/or targeted combination) therapies would be of optimal benefit to the individual patient.

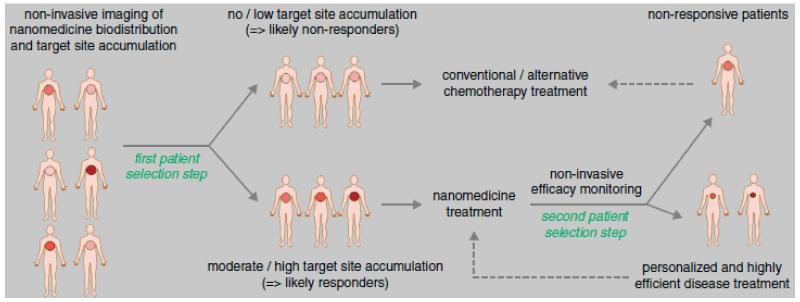

Whereas for classical therapeutics, the mechanism of action, dose and route of administration are the only parameters which can be adjusted, nanomedicines have additional properties which can be fine-tuned. Due to the availability of ever more advanced drug delivery systems, and the possibility of incorporating besides drugs also imaging moieties, allowing for the non-invasive monitoring of biodistribution, target site accumulation, off-target localization and drug release, theranostic nanomedicines hold great potential for personalizing therapies. Image-guided insights into drug delivery, drug release and drug efficacy are highly useful for patient prescreening, in order to identify which tumors are amenable to nanomedicine treatment (e.g. via EPR-mediated passive drug targeting) and which are not, and to thereby predict which patients are likely to respond to a given long-circulating nanomedicine formulation and which are not (Figure 5). Consequently, such image-guided and individualized treatments seem to be highly useful to personalize tumor-targeted nanomedicine treatments [60].

Figure 5.

Nanotheranostics for personalized nanomedicine. Patients to be treated with nanomedicines are to be prescreened prior to therapy with a (radio-) labeled version of the formulation (first patient selection step), in order to identify individuals showing sufficiently high levels of (EPR-mediated) tumor accumulation, and which therefore are more likely to respond to treatment with the targeted nanomedicine formulation in question. During a second patient selection step, individuals showing reasonable target site accumulation but insufficient therapeutic response could be allocated to treatment with alternative therapies, to assure individualized and improved interventions. Figure adapted from [60].

In addition to the ongoing developments in designing (ever more and ever more advanced) nanotheranostics, it might also be essential to implement ‘indirect’ image-guided prescreening protocols to pre-identify patients which are likely to respond to EPR-targeted nanotherapies. Since the target site accumulation of nanomedicines likely depends on image-able parameters, such as relative blood volume, perfusion and permeability, and since it might also correlate with angiogenic vascular marker expression, such as VEGFR2 or integrins, imaging such general functional and molecular hallmarks of the tumor vasculature, and correlating such parameters with EPR-mediated tumor accumulation, might also be highly useful for non-invasively assessing the amenability of tumors for passive drug targeting.

From a clinical point of view, however, directly monitoring EPR-mediated tumor targeting might be more practical. An example for this is based on the abovementioned study by Harrington and colleagues, who in their comparative target site accumulation study showed that different tumor types accumulate nanomedicine formulations with different efficiencies [57]. They e.g. provided pioneering proof-of-principle evidence showing that breast carcinomas might not be the best tumors to be treated with long circulating and passively tumor-targeted liposomes, which is in line with the relatively poor response rates that are observed in the clinic upon therapy with free vs. liposome-encapsulated doxorubicin (progression-free and overall survival times were similar in both cases [61]). Conversely, tumors which are known to accumulate liposomes relatively well, such as head-and-neck carcinomas, and in particular Kaposi sarcomas, are known to respond relatively well to such treatments [62,63]. Consequently, more intensively combining drug targeting and imaging, and using theranostic nanomedicine formulations to predict which patients might respond to nanomedicine treatments, seems to hold significant potential for personalizing and improving anticancer therapy

Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully acknowledge financial support by the German Federal State of North Rhine Westphalia (HighTech.NRW/EU-Ziel 2-Programm (EFRE); ForSaTum), by the German Academic Exchange Service (DAAD; 290084/2011-3), by the DFG (LA 2937/1-2), by the European Union (European Regional Development Fund – Investing In Your Future; and COST – Action TD1004), by the European Research Council (ERC Starting Grant 309495: NeoNaNo).

References

- 1.Hanahan D, Weinberg RA. Hallmarks of cancer: the next generation. Cell. 2011;144(5):646–674. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hanahan D, Weinberg RA. The hallmarks of cancer. Cell. 2000;100(1):57–70. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81683-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Essenberg JM. Cigarette smoke and the incidence of primary neoplasm of the lung in the albino mouse. Science. 1952;116(3021):561–562. doi: 10.1126/science.116.3021.561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hecht SS. Lung carcinogenesis by tobacco smoke. Int J Cancer. 2012;131(12):2724–2732. doi: 10.1002/ijc.27816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fearon ER. Molecular genetics of colorectal cancer. Annu Rev Pathol. 2011;6:479–507. doi: 10.1146/annurev-pathol-011110-130235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lammers T, Hennink WE, Storm G. Tumour-targeted nanomedicines: principles and practice. Br J Cancer. 2008;99(3):392–397. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6604483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jain RK. Lessons from multidisciplinary translational trials on anti-angiogenic therapy of cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2008;8(4):309–316. doi: 10.1038/nrc2346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Duncan R, Gaspar R. Nanomedicine(s) under the microscope. Mol Pharm. 2011;8(6):2101–2141. doi: 10.1021/mp200394t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kunjachan S, Rychlik B, Storm G, Kiessling F, Lammers T. Multidrug resistance: Physiological principles and nanomedical solutions. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2013;65(13-14):1852–1865. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2013.09.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lammers T, Kiessling F, Hennink WE, Storm G. Drug targeting to tumors: principles, pitfalls and (pre-) clinical progress. J Control Release. 2012;161(2):175–187. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2011.09.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jain RK, Stylianopoulos T. Delivering nanomedicine to solid tumors. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2010;7(11):653–664. doi: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2010.139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Duncan R, Vicent MJ. Polymer therapeutics-prospects for 21st century: the end of the beginning. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2013;65(1):60–70. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2012.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Allen TM, Cullis PR. Liposomal drug delivery systems: from concept to clinical applications. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2013;65(1):36–48. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2012.09.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lammers T, Aime S, Hennink WE, Storm G, Kiessling F. Theranostic nanomedicine. Acc Chem Res. 2011;44(10):1029–1038. doi: 10.1021/ar200019c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rizzo LY, Theek B, Storm G, Kiessling F, Lammers T. Recent progress in nanomedicine: therapeutic, diagnostic and theranostic applications. Curr Opin Biotechnol. 2013;24(6):1159–1166. doi: 10.1016/j.copbio.2013.02.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kopecek J. Polymer-drug conjugates: origins, progress to date and future directions. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2013;65(1):49–59. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2012.10.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wang AZ, Langer R, Farokhzad OC. Nanoparticle delivery of cancer drugs. Annu Rev Med. 2012;63:185–198. doi: 10.1146/annurev-med-040210-162544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bangham AD, Standish MM, Watkins JC. Diffusion of univalent ions across the lamellae of swollen phospholipids. J Mol Biol. 1965;13(1):238–252. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(65)80093-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gregoriadis G. Drug entrapment in liposomes. FEBS Lett. 1973;36(3):292–296. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(73)80394-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gregoriadis G, Ryman BE. Liposomes as carriers of enzymes or drugs: a new approach to the treatment of storage diseases. Biochem J. 1971;124(5):58P. doi: 10.1042/bj1240058p. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fenske DB, Cullis PR. Liposomal nanomedicines. Expert Opin Drug Deliv. 2008;5(1):25–44. doi: 10.1517/17425247.5.1.25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ishida T, Iden DL, Allen TM. A combinatorial approach to producing sterically stabilized (Stealth) immunoliposomal drugs. FEBS Lett. 1999;460(1):129–133. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(99)01320-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Klibanov AL, Maruyama K, Torchilin VP, Huang L. Amphipathic polyethyleneglycols effectively prolong the circulation time of liposomes. FEBS Lett. 1990;268(1):235–237. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(90)81016-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Maeda H, Nakamura H, Fang J. The EPR effect for macromolecular drug delivery to solid tumors: Improvement of tumor uptake, lowering of systemic toxicity, and distinct tumor imaging in vivo. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2013;65(1):71–79. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2012.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Maeda H. Macromolecular therapeutics in cancer treatment: the EPR effect and beyond. J Control Release. 2012;164(2):138–144. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2012.04.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Barenholz Y. Doxil(R)--the first FDA-approved nano-drug: lessons learned. J Control Release. 2012;160(2):117–134. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2012.03.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gabizon A, Catane R, Uziely B, Kaufman B, Safra T, Cohen R, Martin F, Huang A, Barenholz Y. Prolonged circulation time and enhanced accumulation in malignant exudates of doxorubicin encapsulated in polyethylene-glycol coated liposomes. Cancer Res. 1994;54(4):987–992. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.May JP, Li SD. Hyperthermia-induced drug targeting. Expert Opin Drug Deliv. 2013;10(4):511–527. doi: 10.1517/17425247.2013.758631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Duncan R, Vicent MJ. Do HPMA copolymer conjugates have a future as clinically useful nanomedicines? A critical overview of current status and future opportunities. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2010;62(2):272–282. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2009.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Duncan R. Polymer conjugates as anticancer nanomedicines. Nat Rev Cancer. 2006;6(9):688–701. doi: 10.1038/nrc1958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Talelli M, Rijcken CJ, Hennink W, Lammers T. Polymeric micelles for cancer therapy: 3 C’s to enhance efficacy. Curr Opin Solid State Mater Sci. 2012;16(6):302–309. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hrkach J, Von Hoff D, Mukkaram Ali M, Andrianova E, Auer J, Campbell T, De Witt D, Figa M, Figueiredo M, Horhota A, Low S, McDonnell K, Peeke E, Retnarajan B, Sabnis A, Schnipper E, Song JJ, Song YH, Summa J, Tompsett D, Troiano G, Van Geen Hoven T, Wright J, LoRusso P, Kantoff PW, Bander NH, Sweeney C, Farokhzad OC, Langer R, Zale S. Preclinical development and clinical translation of a PSMA-targeted docetaxel nanoparticle with a differentiated pharmacological profile. Sci Transl Med. 2012;4(128):128ra139. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3003651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Massoud TF, Gambhir SS. Molecular imaging in living subjects: seeing fundamental biological processes in a new light. Genes Dev. 2003;17(5):545–580. doi: 10.1101/gad.1047403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bzyl J, Lederle W, Palmowski M, Kiessling F. Molecular and functional ultrasound imaging of breast tumors. Eur J Radiol. 2012;81(Suppl 1):S11–12. doi: 10.1016/S0720-048X(12)70005-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Stiller W, Kobayashi M, Koike K, Stampfl U, Richter GM, Semmler W, Kiessling F. Initial Experience with a Novel Low-Dose Micro-CT System. Rofo. 2007;179(7):669–675. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-963189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kiessling F, Morgenstern B, Zhang C. Contrast agents and applications to assess tumor angiogenesis in vivo by magnetic resonance imaging. Curr Med Chem. 2007;14(1):77–91. doi: 10.2174/092986707779313516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kiessling F, Farhan N, Lichy MP, Vosseler S, Heilmann M, Krix M, Bohlen P, Miller DW, Mueller MM, Semmler W, Fusenig NE, Delorme S. Dynamic contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging rapidly indicates vessel regression in human squamous cell carcinomas grown in nude mice caused by VEGF receptor 2 blockade with DC101. Neoplasia. 2004;6(3):213–223. doi: 10.1593/neo.3394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ehling J, Lammers T, Kiessling F. Non-invasive imaging for studying anti-angiogenic therapy effects. Thromb Haemost. 2013;109(3):375–390. doi: 10.1160/TH12-10-0721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tassa C, Shaw SY, Weissleder R. Dextran-coated iron oxide nanoparticles: a versatile platform for targeted molecular imaging, molecular diagnostics, and therapy. Acc Chem Res. 2011;44(10):842–852. doi: 10.1021/ar200084x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jayapaul J, Arns S, Lederle W, Lammers T, Comba P, Gatjens J, Kiessling F. Riboflavin carrier protein-targeted fluorescent USPIO for the assessment of vascular metabolism in tumors. Biomaterials. 2012;33(34):8822–8829. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2012.08.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bzyl J, Lederle W, Rix A, Grouls C, Tardy I, Pochon S, Siepmann M, Penzkofer T, Schneider M, Kiessling F, Palmowski M. Molecular and functional ultrasound imaging in differently aggressive breast cancer xenografts using two novel ultrasound contrast agents (BR55 and BR38) Eur Radiol. 2011;21(9):1988–1995. doi: 10.1007/s00330-011-2138-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bzyl J, Palmowski M, Rix A, Arns S, Hyvelin JM, Pochon S, Ehling J, Schrading S, Kiessling F, Lederle W. The high angiogenic activity in very early breast cancer enables reliable imaging with VEGFR2-targeted microbubbles (BR55) Eur Radiol. 2013;23(2):468–475. doi: 10.1007/s00330-012-2594-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Palmowski M, Huppert J, Ladewig G, Hauff P, Reinhardt M, Mueller MM, Woenne EC, Jenne JW, Maurer M, Kauffmann GW, Semmler W, Kiessling F. Molecular profiling of angiogenesis with targeted ultrasound imaging: early assessment of antiangiogenic therapy effects. Mol Cancer Ther. 2008;7(1):101–109. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-07-0409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kiessling F, Fokong S, Koczera P, Lederle W, Lammers T. Ultrasound microbubbles for molecular diagnosis, therapy, and theranostics. J Nucl Med. 2012;53(3):345–348. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.111.099754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Burgers TA, Hoffmann MF, Collins CJ, Zahatnansky J, Alvarado MA, Morris MR, Sietsema DL, Mason JJ, Jones CB, Ploeg HL, Williams BO. Mice lacking pten in osteoblasts have improved intramembranous and late endochondral fracture healing. PLoS One. 2013;8(5):e63857. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0063857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kunjachan S, Jayapaul J, Mertens ME, Storm G, Kiessling F, Lammers T. Theranostic systems and strategies for monitoring nanomedicine-mediated drug targeting. Curr Pharm Biotechnol. 2012;13(4):609–622. doi: 10.2174/138920112799436302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kiessling F, Mertens ME, Grimm J, Lammers T. Nanoparticles for Imaging: Top or Flop? Radiology. 2014 doi: 10.1148/radiol.14131520. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Nystrom AM, Fadeel B. Safety assessment of nanomaterials: implications for nanomedicine. J Control Release. 2012;161(2):403–408. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2012.01.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Weissleder R, Stark DD, Engelstad BL, Bacon BR, Compton CC, White DL, Jacobs P, Lewis J. Superparamagnetic iron oxide: pharmacokinetics and toxicity. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1989;152(1):167–173. doi: 10.2214/ajr.152.1.167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Weissleder R, Elizondo G, Stark DD, Hahn PF, Marfil J, Gonzalez JF, Saini S, Todd LE, Ferrucci JT. The diagnosis of splenic lymphoma by MR imaging: value of superparamagnetic iron oxide. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1989;152(1):175–180. doi: 10.2214/ajr.152.1.175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Modo M, Hoehn M, Bulte JW. Cellular MR imaging. Mol Imaging. 2005;4(3):143–164. doi: 10.1162/15353500200505145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Gorelik M, Orukari I, Wang J, Galpoththawela S, Kim H, Levy M, Gilad AA, Bar-Shir A, Kerr DA, Levchenko A, Bulte JW, Walczak P. Use of MR cell tracking to evaluate targeting of glial precursor cells to inflammatory tissue by exploiting the very late antigen-4 docking receptor. Radiology. 2012;265(1):175–185. doi: 10.1148/radiol.12112212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kircher MF, Gambhir SS, Grimm J. Noninvasive cell-tracking methods. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2011;8(11):677–688. doi: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2011.141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Mulder WJ, Strijkers GJ, Habets JW, Bleeker EJ, van der Schaft DW, Storm G, Koning GA, Griffioen AW, Nicolay K. MR molecular imaging and fluorescence microscopy for identification of activated tumor endothelium using a bimodal lipidic nanoparticle. FASEB J. 2005;19(14):2008–2010. doi: 10.1096/fj.05-4145fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kunjachan S, Gremse F, Theek B, Koczera P, Pola R, Pechar M, Etrych T, Ulbrich K, Storm G, Kiessling F, Lammers T. Noninvasive optical imaging of nanomedicine biodistribution. ACS Nano. 2013;7(1):252–262. doi: 10.1021/nn303955n. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Seymour LW, Ferry DR, Anderson D, Hesslewood S, Julyan PJ, Poyner R, Doran J, Young AM, Burtles S, Kerr DJ. Hepatic drug targeting: phase I evaluation of polymer-bound doxorubicin. J Clin Oncol. 2002;20(6):1668–1676. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2002.20.6.1668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Harrington KJ, Mohammadtaghi S, Uster PS, Glass D, Peters AM, Vile RG, Stewart JS. Effective targeting of solid tumors in patients with locally advanced cancers by radiolabeled pegylated liposomes. Clin Cancer Res. 2001;7(2):243–254. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Thermodox - Pipeline within a program. Celsion Corporation; [Accessed 9 October 2013]. 2013. http://celsion.com/docs/pipeline_overview [Google Scholar]

- 59.Grull H, Langereis S. Hyperthermia-triggered drug delivery from temperature-sensitive liposomes using MRI-guided high intensity focused ultrasound. J Control Release. 2012;161(2):317–327. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2012.04.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Lammers T, Rizzo LY, Storm G, Kiessling F. Personalized nanomedicine. Clin Cancer Res. 2012;18(18):4889–4894. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-12-1414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Harris L, Batist G, Belt R, Rovira D, Navari R, Azarnia N, Welles L, Winer E, Group TDS. Liposome-encapsulated doxorubicin compared with conventional doxorubicin in a randomized multicenter trial as first-line therapy of metastatic breast carcinoma. Cancer. 2002;94(1):25–36. doi: 10.1002/cncr.10201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.James ND, Coker RJ, Tomlinson D, Harris JR, Gompels M, Pinching AJ, Stewart JS. Liposomal doxorubicin (Doxil): an effective new treatment for Kaposi’s sarcoma in AIDS. Clin Oncol (R Coll Radiol) 1994;6(5):294–296. doi: 10.1016/s0936-6555(05)80269-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Northfelt DW, Dezube BJ, Thommes JA, Miller BJ, Fischl MA, Friedman-Kien A, Kaplan LD, Du Mond C, Mamelok RD, Henry DH. Pegylated-liposomal doxorubicin versus doxorubicin, bleomycin, and vincristine in the treatment of AIDS-related Kaposi’s sarcoma: results of a randomized phase III clinical trial. J Clin Oncol. 1998;16(7):2445–2451. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1998.16.7.2445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]