Abstract

BACKGROUND

Fragile X Syndrome (FXS) is a trinucleotide repeat disease that is caused by the expansion of CGG sequences in the 5’ untranslated region of the FMR1 gene. Molecular diagnoses of FXS and other emerging FMR1 disorders typically rely on two tests, PCR and Southern blotting. However, performance or throughput limitations in these methods currently constrain routine testing.

METHODS

We evaluated a novel FMR1 gene-specific PCR technology with 20 cell line DNA templates and 146 blinded clinical specimens. The CGG repeat number was determined by fragment sizing of PCR amplicons using capillary electrophoresis and compared with the results of FMR1 Southern blotting performed with the same samples.

RESULTS

The FMR1 PCR accurately detected full mutation alleles up to at least 1300 CGG repeats and comprising >99% GC character. All categories of alleles detected by Southern blot, including 66 specimens with full mutations, were also identified by FMR1 PCR for each of 146 clinical specimens. Since all full mutation alleles in heterozygous female samples were detected by PCR, allele zygosity was reconciled in every case. The PCR reagents also detected a 1% mass fraction of a 940 CGG allele in a background of 99% 23 CGG allele—roughly 5-fold greater sensitivity than Southern blotting.

CONCLUSIONS

The novel PCR technology can accurately categorize the spectrum of FMR1 alleles, including alleles previously considered too large to amplify, reproducibly detect low abundance full mutation alleles, and correctly infer homozygosity in female specimens, thus greatly reducing the need for sample reflexing to Southern blot.

INTRODUCTION

Fragile X Syndrome (FXS), the most common form of inherited intellectual impairment and known genetic cause of autism, was one of the first human diseases to be linked to an expansion of triplet nucleotide repeats (1–4). FXS is caused by expansions of the Cytosine-Guanine–Guanine (CGG) repeat sequence located in the 5’UTR of the fragile X mental retardation (FMR1) gene (2). Individuals with normal (<45 CGG repeats) or intermediate (45–54 CGG) FMR1 alleles are currently thought to be asymptomatic for disorders associated with the FMR1 gene. However, individuals who are carriers of a premutation allele (55–200 CGG) can develop fragile X-associated tremor/ataxia syndrome (FXTAS) (5) or fragile X-associated primary ovarian insufficiency (FXPOI) (6–8), whereas subjects with the FMR1 full mutation (>200 CGG) typically have FXS (9). As many as 1.5 million individuals in the US are thought to be at risk for at least one FMR1 disorder (10). Thus, these diseases are clinically significant and impact a broad population and age range.

Currently, most diagnostic testing paradigms for FMR1 disorders rely on PCR with size resolution by capillary electrophoresis (CE), or agarose or polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis to detect up to 100–150 CGG repeats. FMR1 Southern blot analysis is used to characterize samples with CGG repeat numbers too large to amplify by PCR, and to determine the methylation status of the gene (11). Unfortunately, this workflow is costly, time- and labor-intensive, and requires large amounts of genomic DNA, and is thus unsuitable for higher testing volumes or population screening. PCR can potentially address each of these limitations, yet the highly GC-rich character of the fragile X triplet repeat sequence historically has been refractory to amplification. PCR innovations such as the use of osmolyte adjuvants, modified nucleotides, and specific cycling conditions have improved detection up to ~300–500 CGG repeats (12, 13), yet even this performance would fail to detect many, if not most, full mutation alleles (14). Importantly, PCR of premutation and full mutation females has been much less successful due to preferential amplification of the smaller allele (12). Consequently, the >20% of female specimens that are biologically homozygous must be reflexed to Southern blot to resolve the potential ambiguity of an unamplified longer allele.

Here, we report the performance of a novel gene-specific FMR1 PCR technology that can resolve many of the technological challenges that now limit routine fragile X testing. This method reproducibly amplified alleles with greater than 1,000 CGG repeats, and demonstrated excellent concordance with Southern blot in an assessment of clinical specimens whose FMR1 alleles spanned the entire range of CGG repeats. The consistency and sensitivity of the reagents to detect premutation and full mutation alleles, including mosaic species that may only be present in a few percent of cells, also resolved ambiguities in identifying female homozygous samples that can confound conventional FMR1 PCR assays. Reproducible detection of full mutation alleles by PCR has implications for the broader adoption of FMR1 analysis.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Clinical and Cell Line DNA Samples

Blood samples were obtained from subjects evaluated at the M.I.N.D. Institute Clinic, following informed consent and according to an approved Institutional Review Board protocol. Genomic DNA was isolated from peripheral blood leukocytes (5 ml of whole blood) using standard methods (Qiagen, Gentra Puregene Blood Kit). Only the code number was known to the technician who handled the samples. A total of 146 coded samples were sent to Asuragen, Inc. for PCR analysis. All cell line DNA samples were obtained from the Coriell Cell Repositories (CCR, Coriell Institute for Medical Research, Camden, NJ). Clinical and cell line DNA samples were quantified using a NanoDrop spectrophotometer (Thermo Scientific, Wilmington, DE) and diluted in 10 mM Tris, 0.5 mM EDTA, pH 8.8 to 20 ng/µL prior to PCR and stored at −15 to −30°C.

All PCR sample batches included at least one pooled cell line “process control.” The process control was generated from 4 cell line samples—NA20239 (10 ng/µL), NA07541 (5 ng/µL), NA20230 (12 ng/µL), and NA06891 (10 ng/µL)—admixed in deionized water. The use of this control provided product peaks identified using CE corresponding to 20 ± 1, 29 ± 1, 31 ± 1, 54 ± 1, 119 ± 3 and 199 ± 5 CGG repeats.

To evaluate the analytical sensitivity of PCR and Southern blot, a mock female heterozygous control sample was prepared by admixing the DNA isolated from two cell line samples, NA06895 (23 CGG) and NA09237 (940 CGG). These admixes retained the same mass input in each case, 7 µg for Southern blot and 40 ng for PCR wherein the percent mass of the 940 CGG allele was varied from 1% to 100%.

Gene-specific FMR1 PCR

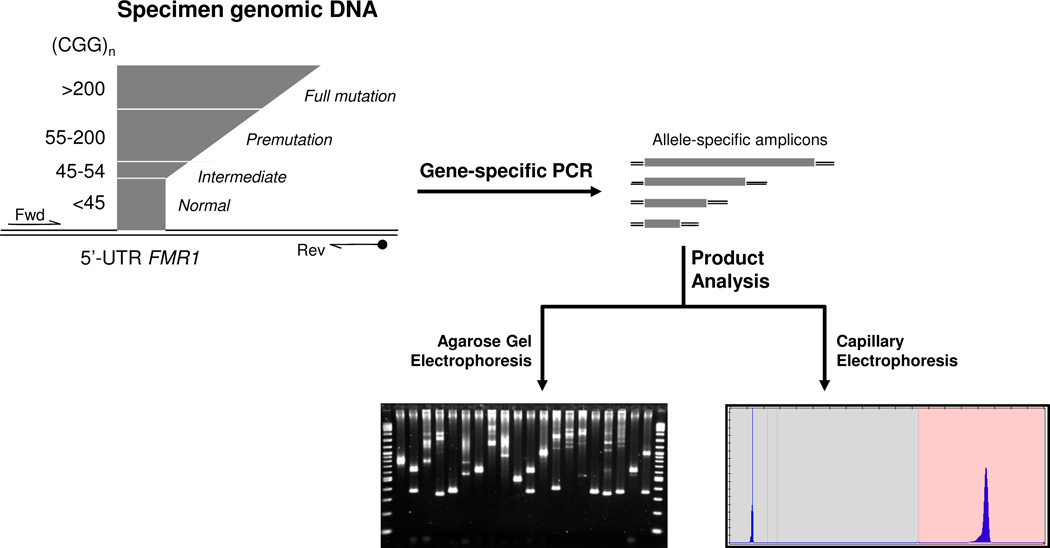

Samples were PCR amplified by preparing a mastermix containing 11.45 µL GC-Rich AMP buffer (#49387), 1.5 µL of FAM-labeled FMR1 Primers (#49386), and 0.05 µL GC-rich Polymerase Mix (#49388) from Asuragen Inc. (Austin, TX). The mastermix was vortexed prior to dispensing to a microtiter plate (96- or 384-well plates, Phenix Research Products, Candler, NC). Aliquots of the DNA sample, typically 2 µL at 20 ng/µL, were transferred to the plate. Sealed plates (ABGene Aluminum, Phenix Research Products) were vortexed, centrifuged and transferred to a thermal cycler (9700, Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). Samples were amplified with an initial heat denature step of 98°C for 5 minutes, followed by 25 cycles of 97°C for 35 sec, 62°C for 35 sec and 72°C for 4 min, and 72°C for 10 minutes. After PCR, samples were stored at −15 to −30 °C protected from light prior to analysis by either agarose gel electrophoresis (AGE) or capillary electrophoresis (CE). A schematic for the technology and workflow is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Workflow for Amplification and Detection of FMR1 amplicons using Novel Fragile X PCR Reagents.

Input genomic DNA is amplified by two gene-specific primers (Fwd and Rev) in a single tube. After amplification, the products, one for each allele present in the reaction, including mosaic alleles, are resolved by CE. The resulting electropherogram is interpreted relative to a sizing ladder to determine the number of CGG repeats for each amplicon. Alternatively, the amplicons can be resolved by agarose gel electrophoresis.

Agarose Gel Electrophoresis (AGE)

A total of 6 µL of the PCR reaction was combined with 3 µL of 3× AGE Loading Dye (15% glycerol and 0.25% bromophenyl blue (Sigma, St. Louis, MO)), and all 9 µL were loaded on a 1.75% agarose gel. Gels were stained with SYBR Gold 10,000X (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) and imaged with UV using an Alpha Innotech FluorChem 8800 Imaging Detection System (Alpha Innotech, San Leandro, CA).

Capillary Electrophoresis (CE)

Except where noted, an ABI 3130xl Genetic Analyzer (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA), running POP-7 polymer (Applied Biosystems) with 36 cm capillaries was used for all experiments. Samples were prepared for CE analysis by mixing 2 µL of the unpurified PCR product with 11 µL of Hi-Di formamide (Applied Biosystems) and 2 µL of a ROX-labeled size ladder (#46083, Asuragen, Inc.). Samples prepared in Hi-Di formamide/ROX-Size ladder were heat denatured at 95°C for 2 min followed by cooling at 4°C for at least 2 min. Except where noted, all injections were 2.5 kV for 20 sec with a 40 min run at 15 kV.

Data Analysis

PCR products analyzed by AGE were sized relative to the MW ladder up to about 1,500 CGG repeats. PCR products detected by CE were analyzed using the GeneMapper 4.0 software (Applied Biosystems). Conversion of peak size in base pairs to number of CGG repeats was determined by referencing the base pair size of the process control alleles to the base pair size of the sample product peaks. Indications of genotype followed ACMG guidelines for normal (NOR) (<45 CGG), intermediate (INT) (45–54 CGG), premutation (PM) (55–200 CGG), and full mutation (FM) (>200 CGG) (9, 15). Full mutation mosaic (Fm) was used only for samples containing both a premutation and a full mutation allele.

Southern Blot

For Southern blot analysis, 7–10 µg of isolated DNA was digested with EcoRI and NruI and separated on a 0.8% agarose/Tris acetate EDTA (TAE) gel. After DNA transfer, the membranes were hybridized with the FMR1-specific genomic probe StB12.3. Additional details of the method are as presented in (16).

RESULTS

Since FMR1 disorders such as FXS, FXPOI, and FXTAS are associated with the number of triplet repeats in the 5’ UTR of the gene, DNA-based assays that interrogate the length of the CGG tract are the methods of choice for molecular testing. Although procedures such as Southern blotting and DNA sequencing can enumerate the repeat segment, these approaches are primarily limited by the number or accuracy of repeat quantification, the amount of genomic DNA material that is required, or workflow considerations that are incompatible with high throughput procedures (17). For these reasons, PCR is the preferred molecular technique. The goal of this study was to characterize a novel set of gene-specific PCR reagents with both cell line and clinical DNA specimens, referenced to Southern blotting results, as a first step in the development of a PCR-only technology for FMR1 analysis.

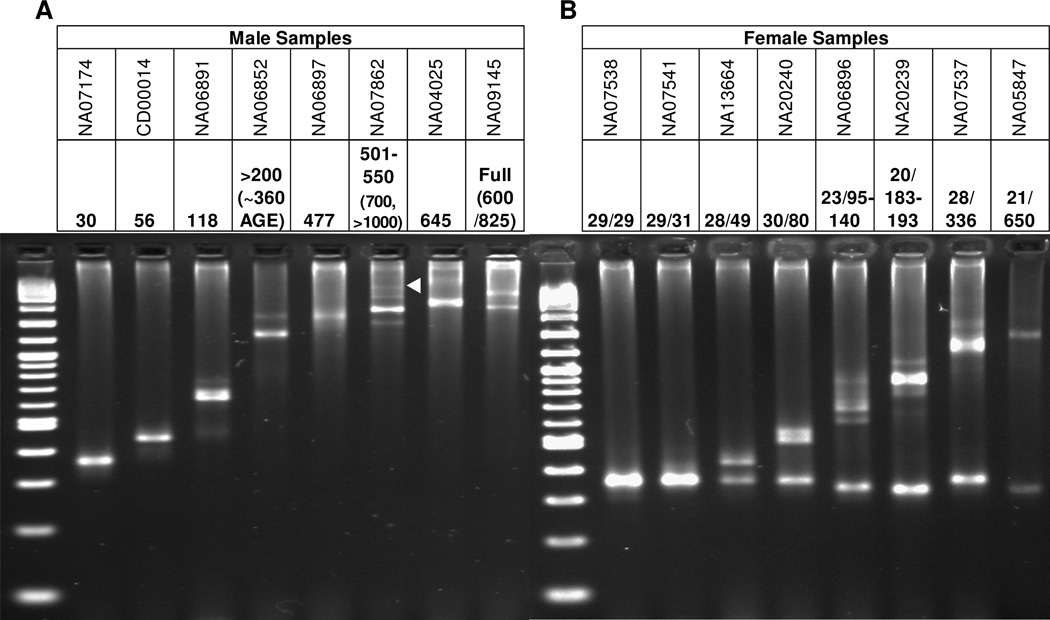

To establish the performance of the gene-specific FMR1 reagents with defined DNA templates, a collection of cell line genomic DNAs (gDNA) from the Coriell Cell Repositories (CCR) were amplified. Products were characterized by both agarose gel electrophoresis (AGE) for both males and females (Figure 2) and capillary electrophoresis (CE) (Suppl Table 1). The number of CGG repeats for each template was extrapolated from the amplicon mobility relative to size standards for both electrophoresis platforms. The DNA templates included several gDNA materials previously assessed by sequencing and/or consensus CGG repeat sizing (18). As shown in Figure 2, the FMR1 reagents amplified cell line templates with CGG repeat numbers spanning all allele categories, from normal to full mutation. Templates with up to ~1,000 repeats were readily detected (see Figure 2A, Lane 6, and Figure 6), both by AGE and CE. In each case, the number of inferred CGG repeats were consistent with those of the reference method (Suppl Table 1).

Figure 2. Gene-specific FMR1 PCR Reagents Detect the Full Range of CGG Repeat Lengths in Both Male and Female Cell Line Genomic DNA templates.

A) PCR products from male gDNA templates. CCR catalog numbers for each template is given at the top with the CCR-provided CGG repeat number below. In cases where repeat quantification was indefinite, estimates from the data were provided by AGE (in parenthesis), as referenced to the MW sizing ladder. The white triangle marks the >1,000 CGG mosaic allele in NA07862. B) PCR products from female gDNA templates. Note that the full mutation band for NA05847 was estimated to be ~420 CGG, rather than 650 CGG.

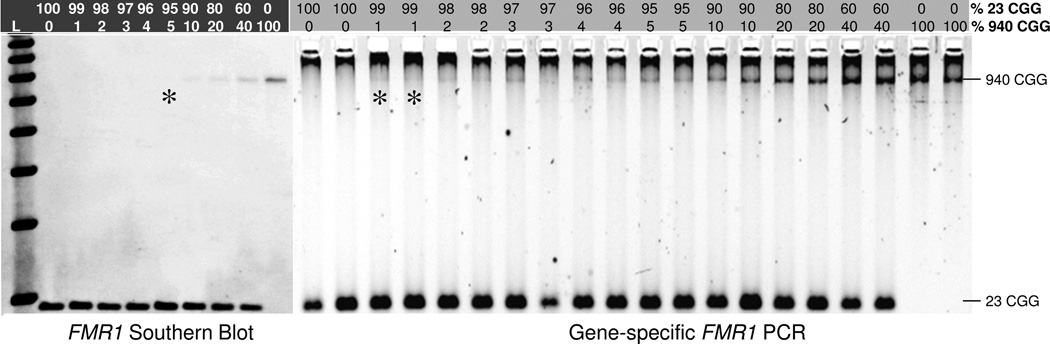

Figure 6. Gene-specific FMR1 PCR is 5-fold More Sensitive than Southern Blotting for the Detection of a Defined Full Mutation Allele.

A total of 7 ug of gDNA was input into the Southern blot, and 40 ng gDNA into PCR. The limit of detection for both methods, expressed as percent 940 CGG full mutation allele in a background of excess 23 CGG allele and as revealed in the original autoradiograph or gel image, is marked with the asterisk.

The results of amplification of a set of female cell line gDNA templates further underscored the efficiency of the PCR reaction. Historically, FMR1 PCR has suffered from biased amplification. This bias is exacerbated by the extremely GC-rich sequence context of the triplet repeat region that favors the more readily amplifiable allele and compounds the difference in product accumulation when both short (e.g., normal) and long (e.g., premutation or full mutation) alleles are present in the same reaction. In contrast, alleles of varying numbers of repeats were readily detected in heterozygous alleles using the gene-specific FMR1 PCR reagents (Figure 2B). Combinations of a half dozen FMR1 alleles spanning the normal to full mutation range (e.g., 20, 29, 119, 199, 336, and 645 CGG) could be each readily co-amplified in the same tube (Suppl Figure 1, Lane 3).

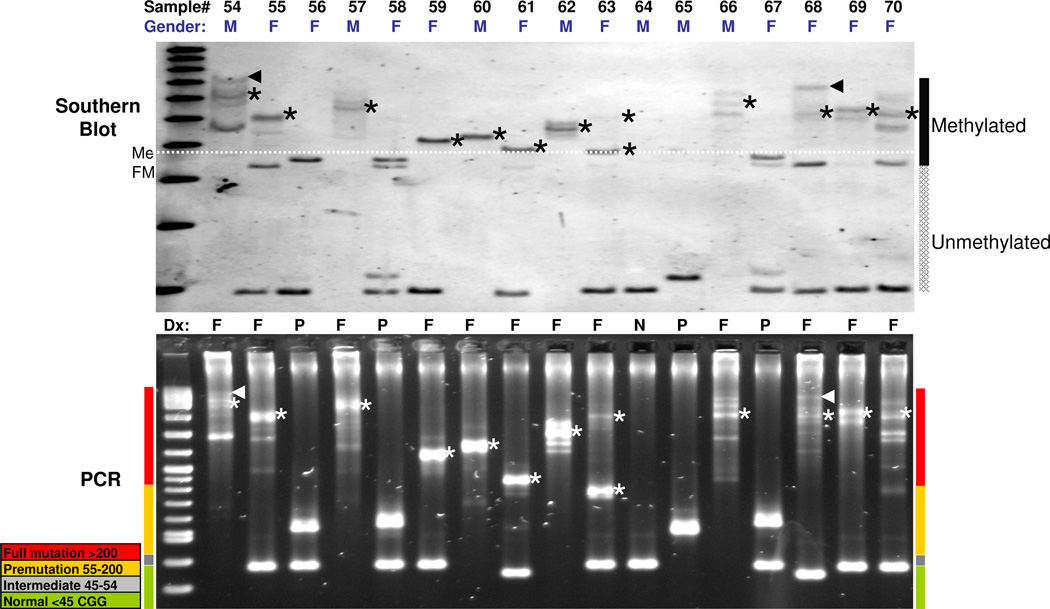

The FMR1 PCR method was next evaluated with a set of blinded 146 clinical specimens provided by the M.I.N.D. Institute at the University of California, Davis, and previously characterized by Southern blot analysis as described (16). Comparative Southern blotting and PCR results for a representative set of 17 specimens from the larger group of 146 specimens are shown in Figure 3. The data demonstrate a striking similarity in pattern distribution and size of the FMR1 alleles. For example, alleles were often represented as multiple bands mirrored by both methods, even for expanded alleles (see lanes corresponding to samples #54, 55, 57, 62, 66, and 68–70). Thus, even though PCR and Southern blot rely on different sample processing and detection modalities, the 5’ UTR species that comprise the CGG repeat regions were consistent in their relative distribution and yield. The agreement in the data between the methods, most notably the sample-specific pattern of complex products, suggests that the PCR and Southern blot methods are highly consistent with one another, and reflective of the true molecular repeat number of patient FMR1 alleles.

Figure 3. FMR1 Southern Blotting and Gene-specific FMR1 PCR Provide Consistent Representations in both the Size and Distribution of Normal and Expanded Alleles.

Top, FMR1 Southern blot results for a set of 17 clinical specimens. Regions of the blot that report unmethylated and methylated alleles are indicated. The white dashed line demarcates the size threshold for >200 CGG alleles that are also methylated. Asterisks in both the Southern blot and AGE gel below the blot denote methylated full mutation alleles mirrored in the PCR results below. The triangle marks indicate 1,300 CGG (sample #54) and 1200 CGG (sample #68) alleles, as sized by both Southern blot and AGE. Bottom, corresponding FMR1 PCR results as resolved by AGE. The colored bars on the sides of the gel image indicate the size of FMR1 amplicons by allele category. Note that the methylation state of some alleles as revealed by Southern blot explains differences in band mobility compared to AGE (particularly #56, 58, and 67).

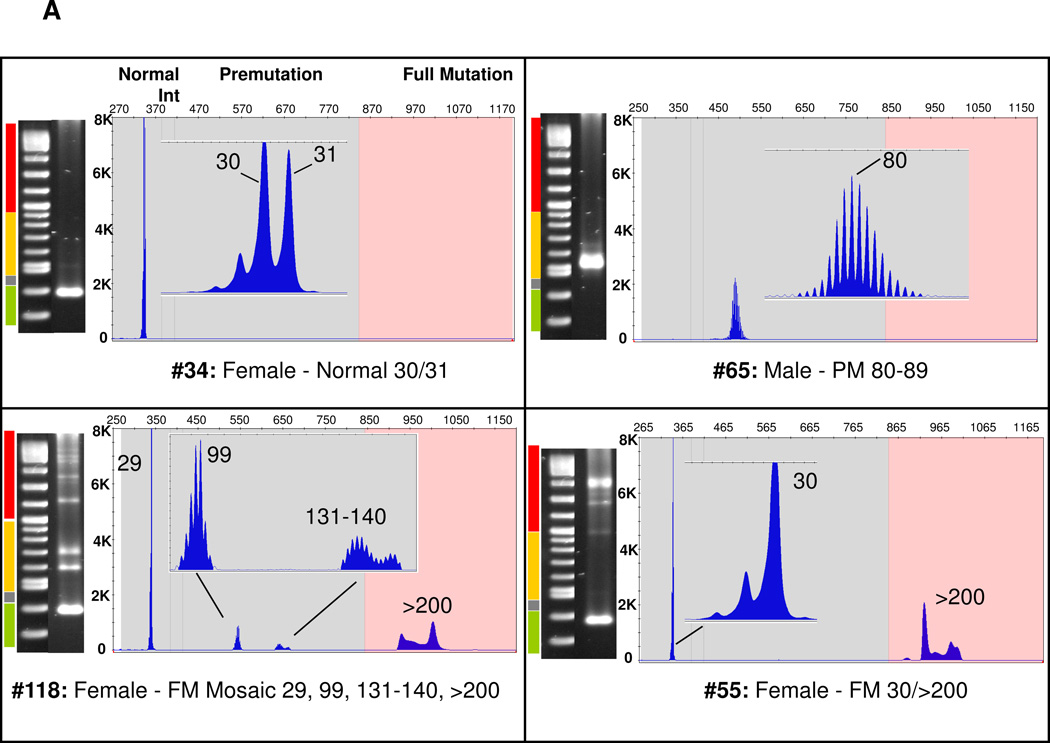

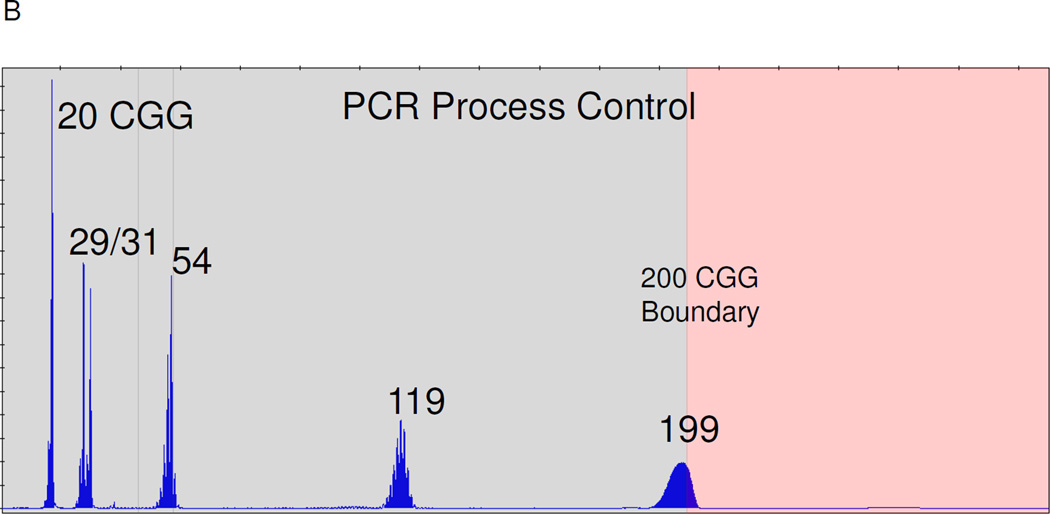

The gene-specific PCR products were also analyzed by capillary electrophoresis (Figure 4). Consistent with the high resolution of this method, heterozygous alleles that differed by a single CGG repeat were readily differentiated (Figure 4A, #34), whereas the limit of resolution of the agarose gel was ~5 CGG for alleles in the normal range (data not shown). Using CE, FMR1 alleles could be accurately sized within 1 CGG up to 70 CGG and 3 CGG to approximately 120 repeats (Suppl Table 1 and (19)). Full mutation alleles, however, could not be resolved beyond about 200 CGG—the repeat threshold for a fragile X full mutation—using the CE configuration described. For example, CE of PCR amplicons from sample #118, which comprised full mutation alleles spanning ~375–1,200 CGG by Southern blotting, revealed a similar peak mobility and morphology as sample #55, which presented alleles of ~450–650 CGG by Southern blotting (Figure 4A). Nevertheless, full mutations identified from the CE analysis were in consistent agreement with categorical assessments of the same amplicons by agarose gel electrophoresis or Southern blot.

Figure 4. Representative AGE and CE Profiles of Normal, Intermediate, Premutation, and Full Mutation FMR1 PCR Amplicons from Male and Female Clinical Specimens.

A) Comparisons of AGE and CE data across all categories of FMR1 alleles. The black vertical line indicates the threshold between a normal, intermediate, or premutation amplicon (left of line) and full mutation amplicon (right of line). “Int,” Intermediate. B) CE electropherogram of a PCR Process Control comprised of 4 cell line gDNA templates of 20, 29, 31, 54, 119, and 199 CGG repeats.

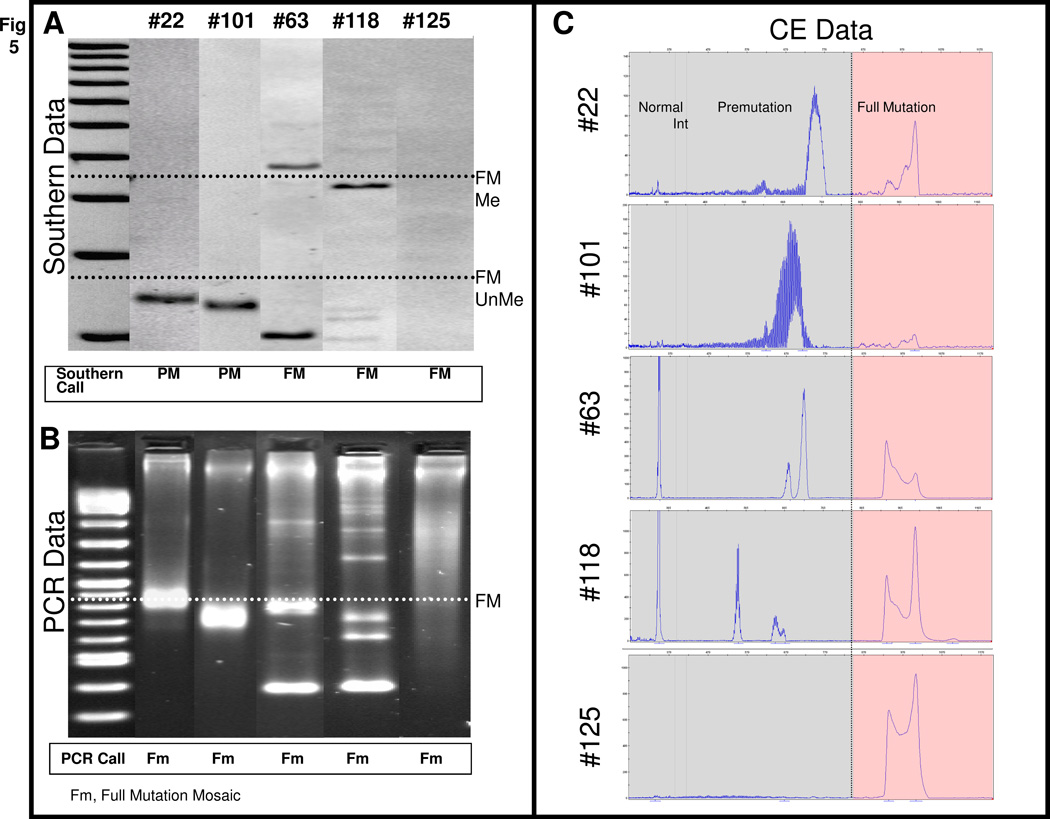

Across the full set of 146 specimens, 42 normal and 3 intermediate samples were identified by both FMR1 Southern blotting and gene-specific PCR. In addition, the Southern blot analysis identified 66 full mutations. All 66 of these samples were also detected as full mutations by gene-specific FMR1 PCR (Suppl Table 2). PCR analysis also identified two samples with full mutation and premutation alleles that were scored as premutations only by Southern blotting (see below). The remaining samples that were categorized as premutations by Southern blotting were exactly concordant with the results from FMR1 PCR.

The two discrepant samples, #22 and #101, revealed prominent premutation-size fragments by both Southern blotting and PCR, but also low intensity full mutation amplicons by PCR when analyzed by CE (Figure 5). Full mutation alleles in other specimens that were only faintly visible by Southern blot were also more clearly detected by PCR/CE. This was particularly true for expanded alleles that spanned a broad size distribution, but were “collapsed” through migration in the CE polymer and thus co-detected as a collection of large amplicons with similar electrophoretic mobilities (Figure 5, #125). This enhanced detection raised the question of whether the PCR/CE method can be more sensitive than Southern blotting for the detection of low abundance alleles.

Figure 5. Gene-specific FMR1 PCR Enables Detection of Low Abundance Expanded Alleles.

A) FMR1 Southern blot data for 5 clinical specimens. The threshold for full mutation (FM, >200 CGG) unmethylated and methylated alleles is designated by the black dotted line. Note that the expanded alleles represented in samples #118 and #125 were very faint, but these were identified as full mutations. B) Corresponding FMR1 PCR data, as visualized by AGE. The threshold for a full mutation (FM) is indicated by the white dotted line. C) Corresponding FMR1 PCR data, as visualized by CE. The threshold for a full mutation (FM) is marked with the black vertical line. To facilitate data interpretation, the Y-axis scale was set to best suit the allele representations for each specimen: #22 (150 RFU), #101 (200 RFU), #63 (1000 RFU), #118 (1100 RFU), and #125 (1100 RFU). Note that the full mutations in #118 and #125 are readily discerned.

To help address this question, we determined the analytical limit of detection of both PCR and Southern blotting after titrating two well-defined male cell line gDNAs, one comprised of a 940 CGG FMR1 allele and the other, 23 CGG. As shown in Figure 6, as little as a 1% mass fraction of the 940 CGG template (400 pg, ~120 gene copies) was detected in a background of 99% 23 CGG allele (39.6 ng). In contrast, a 175-fold higher input of gDNA into the Southern blot revealed a limit of detection of about 5% of the 940 CGG allele. Thus, the FMR1 gene-specific PCR is 5-fold more sensitive than Southern blot (or 5*175=875-fold more sensitive given the differences in the input of 940 CGG allele that was analyzed by the two methods), at least with these gDNA templates. This result is consistent with the observation that full mutation alleles in clinical samples may be identified by PCR when they cannot be detected by Southern blot.

DISCUSSION

Inefficient PCR amplification of the 5’ UTR of the FMR1 gene has long hindered the development of high throughput and automation-friendly fragile X molecular diagnostics. Although a handful of PCR methodologies have been published that can amplify >200 CGG repeats (12, 20–22), all have been limited to the assessment of smaller full mutations, usually in males only. Indeed, protocols currently used by diagnostic laboratories are commonly restricted to detection of 100–150 repeats, and full mutations are often suspected by their failure to amplify, rather than their success (23, 24). As a result, the workflow for fragile X diagnostics relies on Southern blotting to deliver molecular information not currently achievable with PCR. In this report, we describe the performance of an improved FMR1 PCR technology that can reproducibly amplify full mutations in both males and females, including alleles up to at least 1,300 CGG in size—several fold larger than any other published study (12, 13). As such, this technology addresses many of the key problems that have historically limited the utility of FMR1 PCR, and thus can greatly reduce the number of samples that must be reflexed to Southern blot.

A key feature of the FMR1 PCR technology described here is the efficiency by which long CGG repeats can be amplified. Female full mutation specimens provide two FMR1 alleles, typically one that is <40 CGG and one that is >200 CGG. Since the shorter allele is much more readily amplified, this template can outcompete the longer allele during PCR and reduce the yield of full mutation amplicon that would be otherwise produced if the full mutation allele were amplified in isolation. This imbalance is exaggerated with increasing CGG length, as the efficiency of the PCR decreases. The PCR reagents described here, however, produced very “balanced” PCR product yields (Figure 2). In fact, as few as ~120 copies (400 pg) of a 940 CGG allele can be detected in a background of a 99-fold excess of a 23 CGG allele (Figure 6). Moreover, combinations of half a dozen or more alleles, including several full mutation alleles, can be successfully amplified and detected with these reagents (Suppl Figure 1). A practical benefit of this capability is the use of a 6-allele process control that spans normal to full mutation alleles, and was included with all of the PCR reactions performed in this study (Figure 4B).

Performance of the PCR reagents with blinded clinical samples produced an excellent correlation with results from the Southern blotting. Of particular note, all 66 full mutations detected by Southern blot were also detected by FMR1 PCR. Moreover, there was a remarkable similarity in the heterogeneous sample-by-sample allele patterns revealed by comparisons of data produced by the two methods. In addition, two samples with well-defined premutation alleles that were detected by both methods also provided evidence of low abundance full mutation alleles by PCR, but not by Southern blot. An analytical titration of full mutation and normal genomic DNA templates demonstrated that the PCR is 5-fold more sensitive than Southern blot for the detection of the full mutation allele (Figure 6), even after discounting the 175-fold difference in DNA input. Thus, the PCR can report at least some full mutation alleles that are below the limit of detection by Southern blot.

A larger question is, what are the implications of the detection of such low abundance full mutations? Mosaic alleles are present in a subset of the cell population, and, based on the results shown in Figure 6, the FMR1 PCR can theoretically detect full mutation alleles in <5% of cells, and perhaps as few as 1% of cells. On one hand, the lack of FMR1 protein production in such a cell minority is unlikely to have a large impact on the fragile X phenotype. On the other, FMR1 X testing is performed with a clinically accessible specimen (whole blood) that is merely a surrogate for interrogation of the target tissue (brain) that is responsible for the neurological consequences of fragile X syndrome. Case studies have demonstrated discrepancies within the same patient of the number of CGG repeats in whole blood compared to cells, such as epidermal cells, that are more closely related in lineage to brain (25–27). Specimens presenting detectable full mutation alleles in a subset of blood cells may be worthwhile to reflex test in epidermal cells as a way to begin to assess the molecular implications of such low abundance full mutation alleles. This concept may also be relevant to FXPOI, an FMR1 disorder whose biological consequences are realized in cells other than those in whole blood.

The reproducible detection of full mutations by the FMR1 PCR reagents also has important implications for sample reflexing to Southern blot. Currently, laboratories either process every clinical sample on Southern blot (because of the inadequacy of most FMR1 PCR tests), or reflex suspect samples to Southern blot. Such suspect samples may include male specimens that fail to amplify or female specimens that support only a single PCR product. In the latter case, homozygous samples, which represent >20% of all female samples, cannot be distinguished from the heterozygous case with one unamplifiable allele. The capabilities of the novel FMR1 PCR reagents to amplify every full mutation in this study translated to accurate zygosity assessments for all samples. Moreover, the performance of the reagents suggests that only those samples that require methylation information need to be reflexed to Southern blot. Since many laboratories restrict methylation assessments to premutation and full mutation specimens, and these categories represent perhaps 2% of all samples (28), only this small fraction of specimens would require reflex testing. Thus, the PCR capabilities outlined here represent a significant improvement over current procedures, wherein 10–100% of samples are reflexed to Southern blot.

In summary, this PCR technology offers a compelling alternative to both Southern blotting and current PCR methodologies, and represent a critical step toward the elimination of Southern blotting from the fragile X workflow. In addition, the reagents are compatible with PCR-based methylation assessments of FMR1 alleles using methylation-sensitive restriction enzymes. Expanded utility of these PCR reagents using a novel triplet repeat primer design, and their implications for more complete molecular assessments of the FMR1 gene, is described in the companion work (19).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

This project was supported in part by awards from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health & Human Development including R43HD060450 to AGH, HD044410 to FT, and HD040661 to PJH. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health & Human Development or the National Institutes of Health.

REFERENCES

- 1.Hagerman RJ, Hagerman PJ. The fragile X premutation: into the phenotypic fold. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2002;12:278–283. doi: 10.1016/s0959-437x(02)00299-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fu YH, Kuhl DP, Pizzuti A, Pieretti M, Sutcliffe JS, Richards S, et al. Variation of the CGG repeat at the fragile X site results in genetic instability: resolution of the Sherman paradox. Cell. 1991;67:1047–1058. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90283-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Oberle I, Rousseau F, Heitz D, Kretz C, Devys D, Hanauer A, et al. Instability of a 550-base pair DNA segment and abnormal methylation in fragile X syndrome. Science. 1991;252:1097–1102. doi: 10.1126/science.252.5009.1097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Verkerk AJ, Pieretti M, Sutcliffe JS, Fu YH, Kuhl DP, Pizzuti A, et al. Identification of a gene (FMR-1) containing a CGG repeat coincident with a breakpoint cluster region exhibiting length variation in fragile X syndrome. Cell. 1991;65:905–914. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90397-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hagerman RJ, Leehey M, Heinrichs W, Tassone F, Wilson R, Hills J, et al. Intention tremor, parkinsonism, and generalized brain atrophy in male carriers of fragile X. Neurology. 2001;57:127–130. doi: 10.1212/wnl.57.1.127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Allingham-Hawkins DJ, Babul-Hirji R, Chitayat D, Holden JJ, Yang KT, Lee C, et al. Fragile X premutation is a significant risk factor for premature ovarian failure: the International Collaborative POF in Fragile X study--preliminary data. Am J Med Genet. 1999;83:322–325. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Murray A, Ennis S, MacSwiney F, Webb J, Morton NE. Reproductive and menstrual history of females with fragile X expansions. Eur J Hum Genet. 2000;8:247–252. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejhg.5200451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Murray A. Premature ovarian failure and the FMR1 gene. Semin Reprod Med. 2000;18:59–66. doi: 10.1055/s-2000-13476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Maddalena A, Richards CS, McGinniss MJ, Brothman A, Desnick RJ, Grier RE, et al. Technical standards and guidelines for fragile X: the first of a series of disease-specific supplements to the Standards and Guidelines for Clinical Genetics Laboratories of the American College of Medical Genetics. Quality Assurance Subcommittee of the Laboratory Practice Committee. Genet Med. 2001;3:200–205. doi: 10.1097/00125817-200105000-00010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Beckett L, Yu Q, Long AN. The Impact of Fragile X: Prevalence, Numbers Affected, and Economic Impact: A White Paper Prepared for the National Fragile X Foundation. 2005 [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hagerman RJ, Hagerman PJ. Fragile X Syndrome: Diagnosis, Treatment, and Research. 3rd ed. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press; 2002. pp. 3–109. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Saluto A, Brussino A, Tassone F, Arduino C, Cagnoli C, Pappi P, et al. An enhanced polymerase chain reaction assay to detect pre- and full mutation alleles of the fragile X mental retardation 1 gene. J Mol Diagn. 2005;7:605–612. doi: 10.1016/S1525-1578(10)60594-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fernandez-Carvajal I, Lopez Posadas B, Pan R, Raske C, Hagerman PJ, Tassone F. Expansion of an FMR1 grey-zone allele to a full mutation in two generations. J Mol Diagn. 2009;11:306–310. doi: 10.2353/jmoldx.2009.080174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Biacsi R, Kumari D, Usdin K. SIRT1 inhibition alleviates gene silencing in Fragile X mental retardation syndrome. PLoS Genet. 2008;4:e1000017. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kronquist KE, Sherman SL, Spector EB. Clinical significance of tri-nucleotide repeats in Fragile X testing: a clarification of American College of Medical Genetics guidelines. Genet Med. 2008;10:845–847. doi: 10.1097/GIM.0b013e31818b0c8a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tassone F, Pan R, Amiri K, Taylor AK, Hagerman PJ. A rapid polymerase chain reaction-based screening method for identification of all expanded alleles of the fragile X (FMR1) gene in newborn and high-risk populations. J Mol Diagn. 2008;10:43–49. doi: 10.2353/jmoldx.2008.070073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sherman S, Pletcher BA, Driscoll DA. Fragile X syndrome: diagnostic and carrier testing. Genet Med. 2005;7:584–587. doi: 10.1097/01.GIM.0000182468.22666.dd. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Amos Wilson J, Pratt VM, Phansalkar A, Muralidharan K, Highsmith WE, Jr, Beck JC, et al. Consensus characterization of 16 FMR1 reference materials: a consortium study. J Mol Diagn. 2008;10:2–12. doi: 10.2353/jmoldx.2008.070105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chen L, Hadd A, Sah S, Filipovic-Sadic S, Krosting J, Sekinger E, et al. An information-rich CGG repeat primed PCR assay that detects the full range of expanded alleles and minimizes the need for Southern blotting in FMR1 analysis. doi: 10.2353/jmoldx.2010.090227. Submitted. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chong SS, Eichler EE, Nelson DL, Hughes MR. Robust amplification and ethidium-visible detection of the fragile X syndrome CGG repeat using Pfu polymerase. Am J Med Genet. 1994;51:522–526. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.1320510447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhou Y, Law HY, Boehm CD, Yoon CS, Cutting GR, Ng IS, Chong SS. Robust fragile X (CGG)n genotype classification using a methylation specific triple PCR assay. J Med Genet. 2004;41:e45. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2003.012716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Houdayer C, Lemonnier A, Gerard M, Chauve C, Tredano M, de Villemeur TB, et al. Improved fluorescent PCR-based assay for sizing CGG repeats at the FRAXA locus. Clin Chem Lab Med. 1999;37:397–402. doi: 10.1515/CCLM.1999.065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Saul RA, Friez M, Eaves K, Stapleton GA, Collins JS, Schwartz CE, Stevenson RE. Fragile X syndrome detection in newborns-pilot study. Genet Med. 2008;10:714–719. doi: 10.1097/GIM.0b013e3181862a76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Haddad LA, Mingroni-Netto RC, Vianna-Morgante AM, Pena SD. A PCR-based test suitable for screening for fragile X syndrome among mentally retarded males. Hum Genet. 1996;97:808–812. doi: 10.1007/BF02346194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dobkin CS, Nolin SL, Cohen I, Sudhalter V, Bialer MG, Ding XH, et al. Tissue differences in fragile X mosaics: mosaicism in blood cells may differ greatly from skin. Am J Med Genet. 1996;64:296–301. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-8628(19960809)64:2<296::AID-AJMG13>3.0.CO;2-A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Taylor AK, Safanda JF, Fall MZ, Quince C, Lang KA, Hull CE, et al. Molecular predictors of cognitive involvement in female carriers of fragile X syndrome. Jama. 1994;271:507–514. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.MacKenzie JJ, Sumargo I, Taylor SA. A cryptic full mutation in a male with a classical fragile X phenotype. Clin Genet. 2006;70:39–42. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0004.2006.00634.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Strom CM, Crossley B, Redman JB, Buller A, Quan F, Peng M, et al. Molecular testing for Fragile X Syndrome: lessons learned from 119,232 tests performed in a clinical laboratory. Genet Med. 2007;9:46–51. doi: 10.1097/gim.0b013e31802d833c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.