Abstract

Purpose of review

Recent advances in the role of cancer stem cells (CSC) in glioblastoma (GBM) will be reviewed.

Recent findings

In the decade since the description of brain tumor CSCs, the potential significance of these cells in tumor growth, therapeutic resistance and spread has become evident. Most recently, the interplay between CSCs, tumor genetics and the microenvironment has offered potential nodes of fragility under therapeutic development. The CSC phenotype is informed by specific receptor signaling, and the regulation of stem cell genes by transcription factors and miRNAs has identified a number of new targets amenable to treatment. Like normal stem cells, CSC display specific epigenetic landscapes and metabolic profiles.

Summary

Brain cancers activate core stem cell regulatory pathways to empower self-renewal, maintenance of an organ system (albeit an aberrant one), and survival under stress that collectively permits tumor growth, therapeutic resistance, invasion and angiogenesis. These properties have implicated CSC as contributors in GBM progression and recurrence, spurring a search for anti-CSC therapies that do not disrupt normal stem cell maintenance. The past year has witnessed a rapid evolution in the understanding of CSC biology to inform preclinical targeting.

Keywords: Glioblastoma, glioma stem cells, cancer stem cells

Introduction

Glioblastoma (GBM), World Health Organization grade IV astrocytoma, is the most common primary intrinsic brain tumor in adults and remains uniformly fatal despite maximal therapy. Presentation depends on tumor location but symptoms often include headache, paresis, seizures, personality changes, and aphasia. Pathologic grading of astrocytomas is based on a combination of cellular morphology and frequency, mitoses, necrosis and vascular proliferation. Standard-of-care GBM management involves maximal surgical resection followed by chemoradiotherapy and adjuvant chemotherapy with the oral methylating agent, temozolomide. Unfortunately, tumor recurrence is the rule with median survival only 12–15 months for patients under the age of 70 [1].

Neuro-oncology has witnessed an explosion in the molecular modeling of GBM through tumor genetics and mouse modeling. The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) is a large effort with an initial large-scale analysis of primarily new diagnosed GBM designed to quantify common genetic tumor abnormalities that confirmed frequent mutational involvement in the p53, RB, and receptor tyrosine kinase pathways [2]. A competing unbiased whole exome sequencing effort of a smaller number of tumors identified the most exciting novel genetic lesion, isocitrate dehydrogenase 1 (IDH1) gain-of-function mutations, associated with secondary GBM [3]. Gene expression studies divided GBM patients into distinct tumor subtypes -- Classical, Mesenchymal and Proneural -- characterized by mutations in epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR), neurofibromin 1 (NF1), and platelet-derived growth factor receptor A (PDGFRA)/IDH1, respectively [4]. Few of these genetic findings have entered into clinical practice to date.

A link between brain tumors and fetal tissues has long been recognized but it was only a decade ago that several groups simultaneously demonstrated that brain cancers contain hierarchies with highly tumorigenic cells that display stem cell features able to create a complex tumor upon transplantation [5, 6]. This discovery followed earlier reports of tumor initiating populations in leukemia and breast. Similar to CSCs in other cancers, GBM stem cells (GSCs) are defined by their ability to self-renew and propagate heterogeneous tumors in vivo.

Soon after the initial description of GSCs, GSC resistance to conventional therapy -- radiation and chemotherapy -- was described [7, 8]. In addition, GSCs have an increased capacity for angiogenesis and invasion, hallmarks of GBM [9]. While GBMs, like all cancers, are genetic diseases that evolve during treatment, the CSC hypothesis suggests the importance of non-genetic changes in tumor recurrence in patients – GSCs that remain following therapy contribute to regeneration of the patient’s initial tumor. Chen and colleagues modeled this phenomenon in a mouse model of glioma with a Nestin-ΔTK-GFP transgene. The GFP+ cells were suggested to represent a CSC population that remained following temozolomide chemotherapy with additional therapeutic benefit of targeting tumors with the combination of temozolomide and gancyclovir to target the putative CSCs [10]. Although based on a cell line model limiting its relevance to CSCs, a mathematical model of glioma radiotherapy and recurrence predicted that surviving GSCs increased their rate of self-renewal to maintain a tumor following radiotherapy [11]. The collective evidence that CSCs may contribute to our current failure to achieve cures in patients supports the development of molecular targeting strategies.

Initial models of GSC regulation have been based on neural stem cell biology, the probable normal cellular correlate. Indeed, GSCs are governed by pathways active in brain development, including Notch [12], Wnt [13], bone morphogenetic protein (BMP) [14], transforming growth factor-β (TGFβ) [15, 16], and receptor tyrosine kinase (RTK) pathways [17, 18]. More recently, micro-RNAs have been shown play a large role in GSC gene regulation [19, 20] and GSCs display epigenetic DNA changes. Early data suggest that GSCs are metabolically distinct from the bulk tumor population. Furthermore, CSCs are not passive recipients of microenvironmental cues as CSCs stimulate angiogenesis through elaboration of pro-angiogenic growth factors and possible lineage plasticity towards vascular lineages, suggesting both cell autonomous and extrinsically defined CSCs. The CSC state is a plastic phenotype and no single cellular marker is universally informative for CSCs. As such, the study of CSCs requires functional validation and use of patient derived tumors with no or limited time in culture to prevent clonal drift. Thus, CSCs add additional complexity to cancer models with CSCs as potential products of their microenvironment [21–23]. Researchers are attempting to exploit many of these elements of GSC biology to target this population and enhance patient survival.

The Search for GSC-specific Molecular Targets

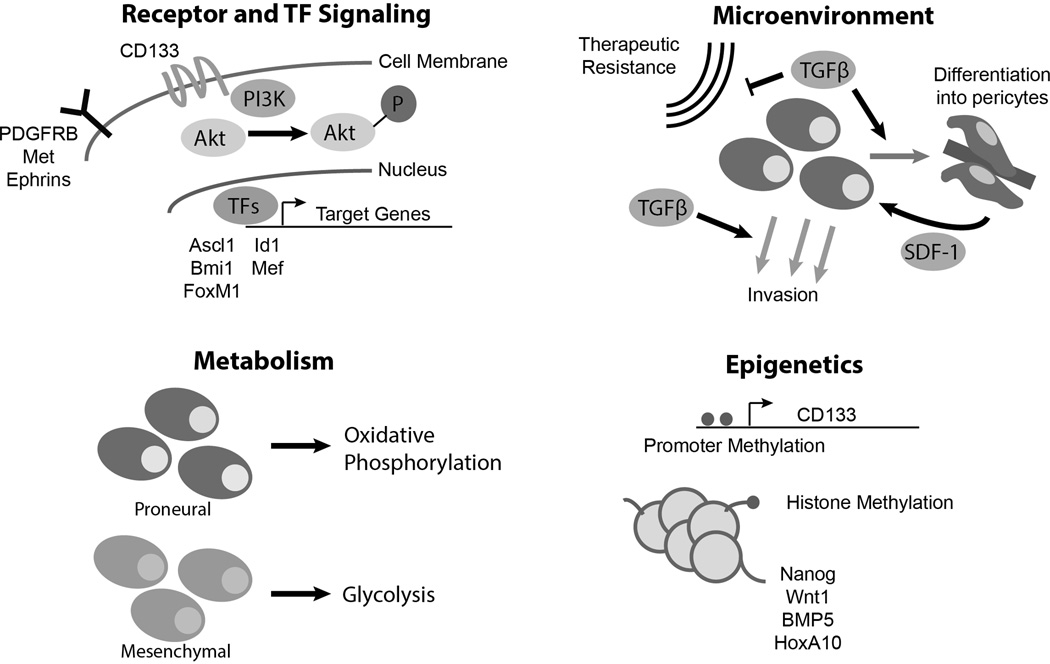

Interrogating GBM models for GSC targets has posed challenges as the field has experienced growing pains with highly variable rigor in the definition of GSCs. Standard culture conditions with serum induce irreversible changes in gene expression profiles divergent from the original tumor, yet many reports persist in the use of cell lines to derive putative GSCs. The CSC hypothesis requires demonstration of a cellular hierarchy of tumorigenic and non-tumorigenic cells. The derivation of sphere-forming cells in serum-free culture enriches for cells with self-renewing features but the corresponding loss of the non-tumorigenic population prevents interpretation of the cellular hierarchy. GSCs should not be considered solely as a replacement for flawed established cell lines, particularly as GSCs receive essential maintenance cues from the microenvironment. Despite these limitations, potentially important therapeutic targets in GSCs have been published on a frequent basis [Fig. 1]. Space limitation prevents discussion of every potential new target, but several recent reports bear attention. One target of particular interest to the field is CD133, or Prominin-1, which has been used for the past decade as a cell surface marker to isolate GSCs for study [5]. The utility of CD133 has been controversial and dependent on context, but a functional role for CD133 has been elucidated in GSCs, as a regulator of the PI3K-Akt pathway via its interactions with the p85 subunit of PI3K [24]. As a cell surface protein, CD133 has been targeted with antibodies in preclinical studies and a vaccine against CD133 (ICT-121) is entering clinical trials.

Figure 1.

Summary of key advances in GSC biology in the past year. (1) New receptors and transcription factor (TF) discoveries in GSCs provide potential new therapeutic targets. (2) Insights into TGF-beta signaling provide clues into the interaction of GSCs and the microenvironment. (3) GSCs activate differential metabolic pathways in a subtype-specific manner. (4) New clues into the epigenetic regulation of the CD133 marker and key stem cell effectors in GSCs.

Numerous receptors have been implicated in GSC biology. The Eph receptor tyrosine kinases have been investigated in cancer and stem cell biology for years [25], but in the last year, two groups independently recognized the roles of the Eph receptors, particularly EphA2 [26] and EphA3 [27], in GSC maintenance. EphA3 was found to be specifically expressed in mesenchymal GSCs and appeared to modulate downstream MAPK signaling. Importantly, both groups were able to target Ephrins in vivo to decrease tumorigenicity in mouse models.

Another receptor that has generated interest in GSCs is platelet-derived growth factor receptor B (PDGFRB). PDGFRA is amplified or mutated commonly in Proneural GBM, suggesting a role in intertumoral heterogeneity. In contrast, PDGFRB is preferentially expressed by GSCs, independent of tumor subgroup, and regulates GSCs through downstream STAT3 signaling to increase invasion and tumorigenicity [28]. Several groups have described MET, the receptor for hepatocyte growth factor (HGF), as a receptor implicated in GSC biology [29, 30]. MET activates wnt/β-catenin signaling in GSCs [31]. In MET high tumors, treatment with HGF induces proliferation, migration and invasion [32]. c-MET inhibitors are in development and c-MET expression may be targeted to sensitize GBMs to anti-angiogenic therapies, supporting potentially direct translation into clinical trials with dual MET/VEGFR2 inhibitors [33].

Transcriptional regulation in GSCs

A tour de force global epigenomic analysis of GSCs performed by Rheinbay et al. revealed selective activation of transcription factors (TFs) compared to normal human astrocytes (NHAs) and ESC-derived neural stem cells (NSCs), including Olig1, Olig2, En2, Hey2, Lhx2, and Ascl1 [34]. Ascl1 proved essential for the maintenance and in vivo tumorigenicity of GSCs through activating Wnt signaling [35]. Targeting TFs is challenging but indirect inhibition of the TF Id1 using the natural compound, cannabidiol, proved useful as an anti-GSC therapy [35]. Examining GSC-specific TFs might also clarify the roles of other proteins involved in GSC biology to further treatment of GBM. For example, the stem cell TF Sox2 is regulated by Polo-like kinase [36] in addition to the TF Myeloid Elf1-like factor (MEF) [37]. Maternal Embryonic Leucine Zipper Kinase (MELK) is a serine/threonine-protein kinase involved in various processes such as cell cycle regulation, self-renewal of stem cells, apoptosis and splicing regulation. As a GSC effector, MELK regulates JNK signaling and its activation of pro-tumorigenic TF FOXM1 [38, 39]. Collectively, the genetic and epigenetic landscape now strongly supports core regulation of a stem-like state in GBM that may inform targeted therapy development.

miRNA and Epigenetic Regulation of GSCs

MiRNAs were first implicated in GSC biology in 2008 [19, 20]. Since then, the field has progressively recognized an essential role of miRNA regulation in many aspects of GSC biology. Last year marked a boon in miRNA research in the field, with a number of novel miRNAs that regulate multiple aspects of GSC signaling. A list of several miRNA targets that were described last year is listed in Table 1. Notably, miR-204 is downregulated in GSCs and targets the transcription factor Sox4 as well as the Eph receptor EphB2 to decrease GSC self-renewal and invasion [49]. Also, miR-18A* promotes the tumorigenic potential of GSCs by targeting DLL3, an inhibitor of Notch signaling [40]. Furthermore, a screen for miRNAs that are altered with serum-induced differentiation identified miR-1275 as a key mediator in oligodendrocytic differentiation of GSCs. miR-1275 is epigenetically silenced by histone H3 lysine 27 trimethylation (H3K27me3) during differentiation, allowing for expression of its target, Claudin11, and a subsequent decrease in proliferation [52].

Table 1.

miRNAs implicated in GSC biology in the past year.

| miRNA | Authors | Relative Expression | Role |

|---|---|---|---|

| miR-18a* | Turchi et al. [40] | Upregulated | Inhibits DLL3, enhancing Notch signaling |

| miR-21 | Polajeva et al. [41] | Upregulated | Co-expressed with Sox2 and promotes growth and survival |

| miR-23b | Geng et al. [42] | Downregulated | Induces cell cycle arrest and inhibits proliferation |

| miR-124 | Wei et al. [43] | Downregulated | Enhances T-Cell mediated clearance of GSCs by inhibiting STAT3 |

| miR-125b | Wu et al. [44] | Downregulated | Inhibits proliferation by targeting E2F2 |

| miR-125b | Shi et al [45] | Downregulated | Inhibits invasion by targeting MMP levels via TIMP3 and RECK |

| miR-137 | Bier et al. [46] | Downregulated | Promotes neural differentiation by targeting RTVP-1 |

| miR-143 | Zhao et al. [47] | Downregulated | Inhibits glycolysis via hexokinase 2, leading to differentiation |

| miR-145 | Lee et al. [48] | Downregulated | Inhibits migration and invasion by targeting CTGF |

| miR-204 | Ying et al. [49] | Downregulated | Targets Sox4 and Ephrin B2 to inhibit self-renewal and invasion |

| miR-211 | Asuthkar et al. [50] | Downregulated | Inhibits migration and invasion by targeting MMP9 |

| miR-452 | Liu et al. [51] | Downregulated | Impacts self-renewal by targeting stem cell factors BMI1, LEF1 and TCF4 |

| miR-1275 | Katsushima et al. [52] | Upregulated | Promotes growth and prevents oligodendrocytic differentiation by targeting Claudin11 |

In addition to the epigenetic regulation of miRNAs and TFs, many other key epigenetic regulators were characterized in GSCs during the past year. BMI1 (B lymphoma Mo-MLV insertion region 1 homolog) is a polycomb ring finger oncogene that serves in the PRC1-like complex to repress gene transcription, including cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitors in cell cycle control. A combination of chromatin immunoprecipitation-sequencing and RNA interference of BMI1 identified Atf3 as a gene upregulated by BMP-mediated differentiation and ER-stress pathways [53]. Atf3 is downregulated in GSCs and its expression promotes the transcription of a number of anti-tumorigenic genes. Another polycomb member, EZH2, has been repeatedly linked to GSCs, with increased significance recently derived from evidence that EZH2 also regulates another GSC signaling node, STAT3, through acetylation [54]. The polycomb family is likely directly involved in GBM tumor initiation as gain-of-function mutations in histone H3 that inhibit polycomb repressive complex 2 (PRC2) activity have been described in pediatric GBM [55]. PRC2 may regulate GSC plasticity through gain or loss of H3K27me3 on pluripotency or development associated genes (e.g. Nanog, Wnt1, BMP5) [56]. Furthermore, mixed lineage leukemia (MLL) maintains GSC characteristics by directly activating the Homeobox gene HOXA10 through its activity of histone methyltransferase at histone H3 lysine 4 [57]. Finally, the expression of CD133, the canonical GSC marker which was functionally characterized this year, was also shown to be regulated by epigenetic mechanisms, as promoter methylation and methyl-DNA-binding proteins cause repression of CD133 by the exclusion of transcription-factor binding [58].

Cancer Metabolism in GSCs

Like all cancers, GBMs display the Warburg effect, a preferential utilization of aerobic glycolysis for energy supplies. This metabolic shift reduces the cells’ oxygen dependence and provides a steady supply of anabolic material yet requires a steady supply of glucose [59]. Whether and how the metabolic pattern differs between GSCs and non-GSCs within the tumor remains elusive, but GSCs may primarily employ oxidative phosphorylation with plasticity as required by metabolic demands [60]. The critical importance of glycolysis has been demonstrated in mesenchymal GSCs, featured by the upregulation of ALDH1A3 and glycolytic activity [61]. Inhibition of ALDH1A3 significantly attenuated the growth of mesenchymal GSCs. Interestingly, such metabolic pattern was not observed in proneural GSCs, indicating that distinct metabolic signaling pathways exist in GSCs from different GBM subtypes. The role of oxidative phosphorylation (OXPHOS) has also been studied in GSCs during the past year. As shown by Janiszewska et al. [62], the oncofetal insulin-like growth factor 2 mRNA-binding protein 2 (IMP2, IGF2BP2) is a key regulator in proneural GSCs in vitro. IMP2 binds and delivers several mRNAs that encode mitochondrial respiratory chain complex subunits to the mitochondria. It also contributes to the assembly of Complex I and Complex IV. More importantly, inhibition of OXPHOS but not of glycolysis abolishes GBM cell clonogenicity in the proneural GSCs. A unifying model would suggest that that glycolysis and OXPHOS are preferentially utilized in mesenchymal and proneural GSCs, respectively, suggesting a potential strategy for a personalized treatment plan based on the metabolic features of GBM subtypes.

GSCs and the Tumor Microenvironment

No stem cell exists in isolation. Similar to normal stem cells, GSCs exist within a tumor niche surrounded by supporting cells such as endothelial cells, pericytes, reactive astrocytes, and tumor-associated macrophages. In addition, GSCs are intimately regulated by microenvironmental factors, and cluster in perivascular [21], hypoxic [22, 63] and likely other niches.

Two years ago, a pair of manuscripts in Nature generated much interest in the field, describing the potential transdifferentiation of glioma stem cells into endothelial cells to contribute to the tumor vasculature [64, 65]. In contradiction, Cheng et al. found such lineage plasticity rare but more common and functionally important transdifferentiation of GSCs into pericytes instead using lineage tracing in vivo [66]. Patient tumor pericytes possess the same genetic abnormalities as tumor cells suggesting a neoplastic origin. The chemokine pathway, CXCL12-CXCR4, mediates an attraction of GSCs to the perivascular niche where TGFβ induces GSCs to assume a pericyte lineage [66]. Two additional publications this year highlight the role of TGFβ in the tumor microenvironment as well, with clear differences in its role based on context. In one paper, TGFβ was implicated as a factor secreted by tumor-associated macrophages to promote GSC-mediated invasion at the tumor edge [67]. In another paper, within tumorspheres – that is, in the environment of other GSCs – GSCs secrete four times more TGFβ per cell than isolated cells. In this context, TGFβ secretion promoted radioresistance of GSCs [68]. Thus, a single microenvironmental factor may be targeted to alter multiple tumor outcomes.

Conclusion

As the cell population in GBM that may contribute to tumor invasion and therapeutic resistance, GSCs have generated much research interest in the past several years. GSCs may be regulated in distinction from neural stem cells, providing potential nodes of fragility. GSC signaling pathways, miRNAs, and epigenetic regulation permit adaptation with the tumor microenvironment to promote tumor invasion, angiogenesis and therapeutic resistance. Last year, mechanisms that endow GSCs with their unique tumorigenic properties have been reported. In addition, we have improved our knowledge on GSC-specific metabolic processes and the interaction between GSCs and the tumor microenvironment. All of these new discoveries have unearthed new opportunities for potential GSC-specific therapies. However, because of the complexity of GSCs, there is unlikely to be an end-all approach to GSC therapy. In order to fight GSCs we must continue to vigorously explore and target all aspects of their biology. Ultimately, we hope to combine the therapies we find with current drugs to prolong the lives of patients with this terrible cancer.

Key bullet points.

-

-

Dysregulated cell-surface receptor and TF signaling in GSCs provide potential targets for therapy.

-

-

miRNA regulation and epigenetic mechanisms impact multiple aspects of GSC biology.

-

-

Proneural GSCs use oxidative phosphorylation while mesenchymal GSCs prefer glycolytic mechanisms, highlighting the importance of tailoring treatments based on GBM subtypes.

-

-

GSCs contribute to and interact with their microenvironment, with TGFβ playing a context-dependent role.

Acknowledgements

We thank our funding sources: The National Institutes of Health grants CA154130 and CA1129958 (J.N.R), grants TR000441 and CA165892 (K. Yan), American Brain Tumor Association (K. Yang), Research Programs Committees of Cleveland Clinic (K. Yang and J.N.R), and James S. McDonnell Foundation (J.N.R).

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest

We have no conflicts of interest to report.

REFERENCES

- 1.Stupp R, Hegi ME, Mason WP, van den Bent MJ, Taphoorn MJ, Janzer RC, et al. Effects of radiotherapy with concomitant and adjuvant temozolomide versus radiotherapy alone on survival in glioblastoma in a randomised phase III study: 5-year analysis of the EORTC-NCIC trial. Lancet Oncol. 2009 May;10(5):459–466. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(09)70025-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Comprehensive genomic characterization defines human glioblastoma genes and core pathways. Nature. 2008 Oct 23;455(7216):1061–1068. doi: 10.1038/nature07385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Parsons DW, Jones S, Zhang X, Lin JC, Leary RJ, Angenendt P, et al. An integrated genomic analysis of human glioblastoma multiforme. Science. 2008 Sep 26;321(5897):1807–1812. doi: 10.1126/science.1164382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Verhaak RG, Hoadley KA, Purdom E, Wang V, Qi Y, Wilkerson MD, et al. Integrated genomic analysis identifies clinically relevant subtypes of glioblastoma characterized by abnormalities in PDGFRA, IDH1, EGFR, and NF1. Cancer Cell. 2010 Jan 19;17(1):98–110. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2009.12.020. [Research Support, N.I.H., Extramural Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov't Research Support, U.S. Gov't, Non-P.H.S.]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Singh SK, Hawkins C, Clarke ID, Squire JA, Bayani J, Hide T, et al. Identification of human brain tumour initiating cells. Nature. 2004 Nov 18;432(7015):396–401. doi: 10.1038/nature03128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hemmati HD, Nakano I, Lazareff JA, Masterman-Smith M, Geschwind DH, Bronner-Fraser M, et al. Cancerous stem cells can arise from pediatric brain tumors. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003 Dec 9;100(25):15178–15183. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2036535100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bao S, Wu Q, McLendon RE, Hao Y, Shi Q, Hjelmeland AB, et al. Glioma stem cells promote radioresistance by preferential activation of the DNA damage response. Nature. 2006 Dec 7;444(7120):756–760. doi: 10.1038/nature05236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Liu G, Yuan X, Zeng Z, Tunici P, Ng H, Abdulkadir IR, et al. Analysis of gene expression and chemoresistance of CD133+ cancer stem cells in glioblastoma. Mol Cancer. 2006;5:67. doi: 10.1186/1476-4598-5-67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bao S, Wu Q, Sathornsumetee S, Hao Y, Li Z, Hjelmeland AB, et al. Stem cell-like glioma cells promote tumor angiogenesis through vascular endothelial growth factor. Cancer Res. 2006 Aug 15;66(16):7843–7848. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-1010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Chen J, Li Y, Yu TS, McKay RM, Burns DK, Kernie SG, et al. A restricted cell population propagates glioblastoma growth after chemotherapy. Nature. 2012 Aug 23;488(7412):522–526. doi: 10.1038/nature11287. ** This paper uses a mouse model to demonstrate glioma regrowth following chemotherapy by a stem-like population.

- 11.Gao X, McDonald JT, Hlatky L, Enderling H. Acute and fractionated irradiation differentially modulate glioma stem cell division kinetics. Cancer Res. 2013 Mar 1;73(5):1481–1490. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-12-3429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wang J, Wakeman TP, Lathia JD, Hjelmeland AB, Wang XF, White RR, et al. Notch promotes radioresistance of glioma stem cells. Stem Cells. 2010 Jan;28(1):17–28. doi: 10.1002/stem.261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jin X, Jeon HY, Joo KM, Kim JK, Jin J, Kim SH, et al. Frizzled 4 regulates stemness and invasiveness of migrating glioma cells established by serial intracranial transplantation. Cancer Res. 2011 Apr 15;71(8):3066–75. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-1495. [Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov't]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Piccirillo SG, Reynolds BA, Zanetti N, Lamorte G, Binda E, Broggi G, et al. Bone morphogenetic proteins inhibit the tumorigenic potential of human brain tumour-initiating cells. Nature. 2006 Dec 7;444(7120):761–765. doi: 10.1038/nature05349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ikushima H, Todo T, Ino Y, Takahashi M, Miyazawa K, Miyazono K. Autocrine TGF-beta signaling maintains tumorigenicity of glioma-initiating cells through Sry-related HMG-box factors. Cell Stem Cell. 2009 Nov 6;5(5):504–514. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2009.08.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Penuelas S, Anido J, Prieto-Sanchez RM, Folch G, Barba I, Cuartas I, et al. TGF-beta increases glioma-initiating cell self-renewal through the induction of LIF in human glioblastoma. Cancer Cell. 2009 Apr 7;15(4):315–327. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2009.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Soeda A, Inagaki A, Oka N, Ikegame Y, Aoki H, Yoshimura S, et al. Epidermal growth factor plays a crucial role in mitogenic regulation of human brain tumor stem cells. J Biol Chem. 2008 Apr 18;283(16):10958–10966. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M704205200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Eyler CE, Foo WC, LaFiura KM, McLendon RE, Hjelmeland AB, Rich JN. Brain cancer stem cells display preferential sensitivity to Akt inhibition. Stem Cells. 2008 Dec;26(12):3027–3036. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2007-1073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Silber J, Lim DA, Petritsch C, Persson AI, Maunakea AK, Yu M, et al. miR-124 and miR-137 inhibit proliferation of glioblastoma multiforme cells and induce differentiation of brain tumor stem cells. BMC Med. 2008;6:14. doi: 10.1186/1741-7015-6-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Godlewski J, Nowicki MO, Bronisz A, Williams S, Otsuki A, Nuovo G, et al. Targeting of the Bmi-1 oncogene/stem cell renewal factor by microRNA-128 inhibits glioma proliferation and self-renewal. Cancer Res. 2008 Nov 15;68(22):9125–9130. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-2629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Calabrese C, Poppleton H, Kocak M, Hogg TL, Fuller C, Hamner B, et al. A perivascular niche for brain tumor stem cells. Cancer Cell. 2007 Jan;11(1):69–82. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2006.11.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Li Z, Bao S, Wu Q, Wang H, Eyler C, Sathornsumetee S, et al. Hypoxia-inducible factors regulate tumorigenic capacity of glioma stem cells. Cancer Cell. 2009 Jun 2;15(6):501–513. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2009.03.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hjelmeland AB, Wu Q, Heddleston JM, Choudhary GS, MacSwords J, Lathia JD, et al. Acidic stress promotes a glioma stem cell phenotype. Cell Death Differ. 2011 May;18(5):829–840. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2010.150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Wei Y, Jiang Y, Zou F, Liu Y, Wang S, Xu N, et al. Activation of PI3K/Akt pathway by CD133-p85 interaction promotes tumorigenic capacity of glioma stem cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013 Apr 23;110(17):6829–6834. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1217002110. * This is the first demonstration of a functional role of the glioma stem cell marker CD133.

- 25.Pasquale EB. Eph-ephrin bidirectional signaling in physiology and disease. Cell. 2008 Apr 4;133(1):38–52. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Binda E, Visioli A, Giani F, Lamorte G, Copetti M, Pitter KL, et al. The EphA2 receptor drives self-renewal and tumorigenicity in stem-like tumor-propagating cells from human glioblastomas. Cancer Cell. 2012 Dec 11;22(6):765–780. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2012.11.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Day BW, Stringer BW, Al-Ejeh F, Ting MJ, Wilson J, Ensbey KS, et al. EphA3 maintains tumorigenicity and is a therapeutic target in glioblastoma multiforme. Cancer Cell. 2013 Feb 11;23(2):238–248. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2013.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kim Y, Kim E, Wu Q, Guryanova O, Hitomi M, Lathia JD, et al. Platelet-derived growth factor receptors differentially inform intertumoral and intratumoral heterogeneity. Genes Dev. 2012 Jun 1;26(11):1247–1262. doi: 10.1101/gad.193565.112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Joo KM, Jin J, Kim E, Ho Kim K, Kim Y, Gu Kang B, et al. MET signaling regulates glioblastoma stem cells. Cancer Res. 2012 Aug 1;72(15):3828–3838. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-11-3760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Li Y, Li A, Glas M, Lal B, Ying M, Sang Y, et al. c-Met signaling induces a reprogramming network and supports the glioblastoma stem-like phenotype. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011 Jun 14;108(24):9951–9956. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1016912108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kim KH, Seol HJ, Kim EH, Rheey J, Jin HJ, Lee Y, et al. Wnt/beta-catenin signaling is a key downstream mediator of MET signaling in glioblastoma stem cells. Neuro Oncol. 2013 Feb;15(2):161–171. doi: 10.1093/neuonc/nos299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.De Bacco F, Casanova E, Medico E, Pellegatta S, Orzan F, Albano R, et al. The MET oncogene is a functional marker of a glioblastoma stem cell subtype. Cancer Res. 2012 Sep 1;72(17):4537–4550. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-11-3490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jahangiri A, De Lay M, Miller LM, Carbonell WS, Hu YL, Lu K, et al. Gene expression profile identifies tyrosine kinase c-Met as a targetable mediator of antiangiogenic therapy resistance. Clin Cancer Res. 2013 Apr 1;19(7):1773–1783. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-12-1281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Rheinbay E, Suva ML, Gillespie SM, Wakimoto H, Patel AP, Shahid M, et al. An aberrant transcription factor network essential for wnt signaling and stem cell maintenance in glioblastoma. Cell Rep. 2013 May 30;3(5):1567–1579. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2013.04.021. ** In this paper, epigenomic analyses have identified widespread activation of a family of transcription factors in glioma.

- 35.Soroceanu L, Murase R, Limbad C, Singer E, Allison J, Adrados I, et al. Id-1 is a key transcriptional regulator of glioblastoma aggressiveness and a novel therapeutic target. Cancer Res. 2013 Mar 1;73(5):1559–1569. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-12-1943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lee C, Fotovati A, Triscott J, Chen J, Venugopal C, Singhal A, et al. Polo-like kinase 1 inhibition kills glioblastoma multiforme brain tumor cells in part through loss of SOX2 and delays tumor progression in mice. Stem Cells. 2012 Jun;30(6):1064–1075. doi: 10.1002/stem.1081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bazzoli E, Pulvirenti T, Oberstadt MC, Perna F, Wee B, Schultz N, et al. MEF promotes stemness in the pathogenesis of gliomas. Cell Stem Cell. 2012 Dec 7;11(6):836–844. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2012.09.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Joshi K, Banasavadi-Siddegowda Y, Mo X, Kim SH, Mao P, Kig C, et al. MELK-Dependent FOXM1 Phosphorylation is Essential for Proliferation of Glioma Stem Cells. Stem Cells. 2013 Jun;31(6):1051–1063. doi: 10.1002/stem.1358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gu C, Banasavadi-Siddegowda YK, Joshi K, Nakamura Y, Kurt H, Gupta S, et al. Tumor-specific activation of the C-JUN/MELK pathway regulates glioma stem cell growth in a p53-dependent manner. Stem Cells. 2013 May;31(5):870–881. doi: 10.1002/stem.1322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Turchi L, Debruyne DN, Almairac F, Virolle V, Fareh M, Neirijnck Y, et al. Tumorigenic Potential of miR-18A* in Glioma Initiating Cells Requires NOTCH-1 Signaling. Stem Cells. 2013 Mar 26; doi: 10.1002/stem.1373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Polajeva J, Swartling FJ, Jiang Y, Singh U, Pietras K, Uhrbom L, et al. miRNA-21 is developmentally regulated in mouse brain and is co-expressed with SOX2 in glioma. BMC Cancer. 2012;12:378. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-12-378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Geng J, Luo H, Pu Y, Zhou Z, Wu X, Xu W, et al. Methylation mediated silencing of miR-23b expression and its role in glioma stem cells. Neurosci Lett. 2012 Oct 24;528(2):185–189. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2012.08.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wei J, Wang F, Kong LY, Xu S, Doucette T, Ferguson SD, et al. miR-124 Inhibits STAT3 Signaling to Enhance T Cell-Mediated Immune Clearance of Glioma. Cancer Res. 2013 Jun 21; doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-12-4318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wu N, Xiao L, Zhao X, Zhao J, Wang J, Wang F, et al. miR-125b regulates the proliferation of glioblastoma stem cells by targeting E2F2. FEBS Lett. 2012 Nov 2;586(21):3831–3839. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2012.08.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Shi L, Wan Y, Sun G, Gu X, Qian C, Yan W, et al. Functional differences of miR-125b on the invasion of primary glioblastoma CD133-negative cells and CD133-positive cells. Neuromolecular Med. 2012 Dec;14(4):303–316. doi: 10.1007/s12017-012-8188-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bier A, Giladi N, Kronfeld N, Lee HK, Cazacu S, Finniss S, et al. MicroRNA-137 is downregulated in glioblastoma and inhibits the stemness of glioma stem cells by targeting RTVP-1. Oncotarget. 2013 May;4(5):665–676. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zhao S, Liu H, Liu Y, Wu J, Wang C, Hou X, et al. miR-143 inhibits glycolysis and depletes stemness of glioblastoma stem-like cells. Cancer Lett. 2013 Jun 10;333(2):253–260. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2013.01.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lee HK, Bier A, Cazacu S, Finniss S, Xiang C, Twito H, et al. MicroRNA-145 is downregulated in glial tumors and regulates glioma cell migration by targeting connective tissue growth factor. PLoS One. 2013;8(2):e54652. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0054652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ying Z, Li Y, Wu J, Zhu X, Yang Y, Tian H, et al. Loss of miR-204 expression enhances glioma migration and stem cell-like phenotype. Cancer Res. 2013 Jan 15;73(2):990–999. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-12-2895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Asuthkar S, Velpula KK, Chetty C, Gorantla B, Rao JS. Epigenetic regulation of miRNA-211 by MMP-9 governs glioma cell apoptosis, chemosensitivity and radiosensitivity. Oncotarget. 2012 Nov;3(11):1439–1454. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Liu L, Chen K, Wu J, Shi L, Hu B, Cheng S, et al. Downregulation of miR-452 Promotes Stem-Like Traits and Tumorigenicity of Gliomas. Clin Cancer Res. 2013 Jun 14; doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-12-3794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Katsushima K, Shinjo K, Natsume A, Ohka F, Fujii M, Osada H, et al. Contribution of microRNA-1275 to Claudin11 protein suppression via a polycomb-mediated silencing mechanism in human glioma stem-like cells. J Biol Chem. 2012 Aug 10;287(33):27396–27406. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.359109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Gargiulo G, Cesaroni M, Serresi M, de Vries N, Hulsman D, Bruggeman SW, et al. In Vivo RNAi Screen for BMI1 Targets Identifies TGF-beta/BMP-ER Stress Pathways as Key Regulators of Neural- and Malignant Glioma-Stem Cell Homeostasis. Cancer Cell. 2013 May 13;23(5):660–676. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2013.03.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kim E, Kim M, Woo DH, Shin Y, Shin J, Chang N, et al. Phosphorylation of EZH2 Activates STAT3 Signaling via STAT3 Methylation and Promotes Tumorigenicity of Glioblastoma Stem-like Cells. Cancer Cell. 2013 Jun 10;23(6):839–852. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2013.04.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Lewis PW, Muller MM, Koletsky MS, Cordero F, Lin S, Banaszynski LA, et al. Inhibition of PRC2 activity by a gain-of-function H3 mutation found in pediatric glioblastoma. Science. 2013 May 17;340(6134):857–861. doi: 10.1126/science.1232245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Natsume A, Ito M, Katsushima K, Ohka F, Hatanaka A, Shinjo K, et al. Chromatin regulator PRC2 is a key regulator of epigenetic plasticity in glioblastoma. Cancer Res. 2013 May 29; doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-13-0109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Gallo M, Ho J, Coutinho FJ, Vanner R, Lee L, Head R, et al. A tumorigenic MLL-homeobox network in human glioblastoma stem cells. Cancer Res. 2013 Jan 1;73(1):417–427. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-12-1881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Gopisetty G, Xu J, Sampath D, Colman H, Puduvalli VK. Epigenetic regulation of CD133/PROM1 expression in glioma stem cells by Sp1/myc and promoter methylation. Oncogene. 2012 Sep 3; doi: 10.1038/onc.2012.331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Vander Heiden MG, Cantley LC, Thompson CB. Understanding the Warburg effect: the metabolic requirements of cell proliferation. Science. 2009 May 22;324(5930):1029–1033. doi: 10.1126/science.1160809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Vlashi E, Lagadec C, Vergnes L, Matsutani T, Masui K, Poulou M, et al. Metabolic state of glioma stem cells and nontumorigenic cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011 Sep 20;108(38):16062–16067. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1106704108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Mao P, Joshi K, Li J, Kim SH, Li P, Santana-Santos L, et al. Mesenchymal glioma stem cells are maintained by activated glycolytic metabolism involving aldehyde dehydrogenase 1A3. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013 May 21;110(21):8644–8649. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1221478110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Janiszewska M, Suva ML, Riggi N, Houtkooper RH, Auwerx J, Clement-Schatlo V, et al. Imp2 controls oxidative phosphorylation and is crucial for preserving glioblastoma cancer stem cells. Genes Dev. 2012 Sep 1;26(17):1926–1944. doi: 10.1101/gad.188292.112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Heddleston JM, Li Z, McLendon RE, Hjelmeland AB, Rich JN. The hypoxic microenvironment maintains glioblastoma stem cells and promotes reprogramming towards a cancer stem cell phenotype. Cell Cycle. 2009 Oct 15;8(20):3274–3284. doi: 10.4161/cc.8.20.9701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Wang R, Chadalavada K, Wilshire J, Kowalik U, Hovinga KE, Geber A, et al. Glioblastoma stem-like cells give rise to tumour endothelium. Nature. 2010 Dec 9;468(7325):829–833. doi: 10.1038/nature09624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Ricci-Vitiani L, Pallini R, Biffoni M, Todaro M, Invernici G, Cenci T, et al. Tumour vascularization via endothelial differentiation of glioblastoma stem-like cells. Nature. 2010 Dec 9;468(7325):824–828. doi: 10.1038/nature09557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Cheng L, Huang Z, Zhou W, Wu Q, Donnola S, Liu JK, et al. Glioblastoma stem cells generate vascular pericytes to support vessel function and tumor growth. Cell. 2013 Mar 28;153(1):139–152. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.02.021. * This paper describes the differentiation of GSCs into pericytes to support the tumor vasculature.

- 67.Ye XZ, Xu SL, Xin YH, Yu SC, Ping YF, Chen L, et al. Tumor-associated microglia/macrophages enhance the invasion of glioma stem-like cells via TGF-beta1 signaling pathway. J Immunol. 2012 Jul 1;189(1):444–453. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1103248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Hardee ME, Marciscano AE, Medina-Ramirez CM, Zagzag D, Narayana A, Lonning SM, et al. Resistance of glioblastoma-initiating cells to radiation mediated by the tumor microenvironment can be abolished by inhibiting transforming growth factor-beta. Cancer Res. 2012 Aug 15;72(16):4119–4129. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-12-0546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]