Abstract

Background

Approximately 1.7 million Americans are diagnosed with cancer annually. There is an increasing demand for high-quality cancer care; however, what constitutes quality care is not well defined. There remains a gap in our knowledge regarding the current perceptions of what defines quality care.

Objective

To review the current understanding and perspectives of key stakeholders regarding quality cancer care for adult patients with cancer who are receiving chemotherapy-based treatment regimens.

Methods

This systematic qualitative literature review involved a search of MEDLINE and PubMed databases for articles that were published between January 2009 and May 2013 using a predefined search strategy with specific Medical Subject Headings terms encompassing 3 core concepts—cancer, chemotherapy, and quality of healthcare. Articles were eligible to be included if they focused on adult cancers, discussed quality indicators of cancer care or quality of care in the article's body, discussed treating cancer with chemotherapy, were conducted in the United States and with US respondents, and reported data about cancer quality that were obtained directly from stakeholders (eg, patients, caregivers, providers, payers, other healthcare professionals). Thematic analyses were conducted to assess the perspectives and the intersection of quality care issues from each stakeholder group that was identified, including patients, providers, and thought leaders.

Results

The search strategy identified 542 articles that were reviewed for eligibility. Of these articles, 15 were eligible for inclusion in the study and reported perspectives from a total of 4934 participants. Patients with cancer, as well as providers, noted information needs, psychosocial support, responsibility for care, and coordination of care as important aspects of quality care. Providers also reported the importance of equity in cancer care and reimbursement concerns, whereas patients with cancer considered the timeliness of care an important factor. The perspectives of thought leaders focused on barriers to and facilitators of quality care.

Conclusion

Thematic elements related to cancer quality were relatively consistent between patients and providers; no additional information was found regarding payer perspectives. The perspectives of these groups are important to consider as quality initiatives are being developed.

According to the American Cancer Society, more than 1.6 million people will receive a new diagnosis of cancer in 2013.1 It is also estimated that there were almost 14 million cancer survivors (ie, any living person who has ever received a diagnosis of cancer) in the United States in 2012.2 Although many aggressive forms of cancer still exist, individuals who receive a diagnosis of cancer today are less likely to die from their disease than in the past; the death rate from cancer has decreased by 20% since 1991.1 However, the number of cancer diagnoses is increasing, and it is expected that there will be more than 18 million cancer survivors in the United States in the next decade.2

Representing a set of heterogeneous diseases, the term “cancer” refers to a diagnosis that is increasingly becoming a chronic condition. Patient care is shifting from a model that was focused on the immediate need to treat the tumor to a more holistic approach in the care of the patient to ensure both quantity and quality of life. The consideration of these needs begins before the active treatment phase and continues after the transition to long-term survivorship.

KEY POINTS

-

▸

With an increasing number of cancer diagnoses and the development of quality initiatives, there is a growing demand for high-quality cancer care.

-

▸

However, quality care is currently ill-defined, and a uniform understanding of what constitutes quality care is still lacking.

-

▸

This study sought to describe perspectives of various stakeholders about quality cancer care.

-

▸

Using search criteria that included cancer, chemotherapy, and quality healthcare, 15 articles published between January 2009 and May 2013 were eligible for inclusion, representing perspectives from a total of 4934 patients with cancer, providers, caregivers, and thought leaders.

-

▸

Information needs, psychosocial support, responsibility for care, and coordination of care were indicated by patients and providers as important components of quality cancer care.

-

▸

Providers also noted the importance of equity in cancer care and reimbursement concerns.

-

▸

Perspectives from thought leaders focused on barriers to and on facilitators of quality care.

-

▸

These themes can serve as a starting point for future initiatives designed to improve quality cancer care and help identify quality measures that are important to patients and providers.

This shift from acute cancer care to treating cancer as a chronic disease has corresponded with the more recent focus on quality cancer care; however, the relationship between these trends and general attitudes about cancer care is unclear.

A number of cancer quality-focused initiatives are ongoing to ensure and assess the quality of cancer care in the United States. These range from legal requirements, such as the Quality Reporting Program for Prospective Payment System–Exempt Cancer Hospitals (Patient Protection and Affordability Care Act, Section 2701 includes mandatory quality reporting requirements, and Section 3005 is specific to cancer hospitals),3 to completely voluntary quality initiatives, such as the Quality Oncology Practice Initiative (QOPI) and its certification system,4 and initiatives led by the Institute of Medicine, such as Improving the Quality of Cancer Care: Addressing the Challenges of an Aging Population (www.iom.edu/Activities/Quality/QualityCancerCareAging.aspx).

Cancer quality measures are being developed by many groups with different or overlapping goals. For example, the National Quality Forum (NQF) (www.qualityforum.org) sets standards and recommends and endorses measures for quality performance in anticipation of the increase in pay-for-performance reimbursement systems. The Physician Quality Reporting System (PQRS), which is sponsored by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (www.cms.gov/PQRS), is focused on payment incentives and adjustments to enhance quality reporting measures.3 Measures may be coendorsed by the NQF and the PQRS. The National Committee for Quality Assurance (www.ncqa.org) is a not-for-profit organization that is focused on care structure and the process of care delivery, and it offers a variety of accreditation and certification programs to ensure quality care.

The largest oncologist organization in the United States, the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO), initiated the QOPI program to be a physician-led initiative that promotes improvement in cancer care by oncologists through self-assessment via specific retrospective chart review procedures.4 The National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) collaborated with ASCO to develop a set of measures that are now being used in the QOPI program. The Community Oncology Alliance (www.communityoncology.org) is a nonprofit organization that is designed to protect the community oncology care delivery system in the United States, with the primary goal of ensuring patient access to quality cancer care.

Many other specialist organizations (eg, Society of Thoracic Surgeons, American Medical Association, College of American Pathologists) have measures that are focused on specific cancers that are not part of the larger disease site–specific measures that are already within the NQF and PQRS tools. As the measures are being developed, what is being measured will ultimately determine how quality is defined; hence the importance of efforts to develop the measures that will assess what is important to the key stakeholders in cancer care (ie, the patients, providers, and payers) cannot be understated.

Patients, caregivers, providers, managed care organizations, payers, and other stakeholder groups have all communicated their interests in improving the quality of cancer care. However, what a patient defines as quality care may not always correspond with how the groups that are developing the key quality measures perceive as quality care. Improvement in quality care could have a very different inherent meaning across stakeholder groups, and discrepancies in values may not be reflected in the measures being created by the various groups. Therefore, it is important to understand the values of each stakeholder through their perceptions of quality in cancer care.

As measures are being developed, it will be important that the patient voice, as well as the voices of others, be adequately represented, or there will be a risk of focusing quality-of-care improvement efforts in such a way as to have no meaning to the recipient of that care.

A previous literature review was conducted by Eli Lilly and Company (Indianapolis, IN) and RTI Health Solutions (Research Triangle Park, NC) on perspectives of quality care in the published literature from 1996 through 2009.5 The study identified 25 published articles that assessed perspectives of quality care. The authors reported the key promoters to quality that were identified by patients (eg, communication, trust, caring behavior and comfort, social and spiritual support), barriers to quality care that were identified by patients (eg, getting health information, lack of coordinated care, lack of psychosocial care, delays in care, billing issues), concerns of providers (eg, workload or administrative burden, lack of coordinated care, bureaucracy of managed care, lack of processes to support treatment guidelines), and the strategies being implemented by managed care to address cancer quality (eg, decision support tools, pathways, guidelines, and cost reduction strategies).5

Each of these perspectives provides insight as to how quality care is interpreted and defined. However, the payer–provider–patient landscape has been changing rapidly in recent years, and trends and perspectives are likely to have changed since 2009. Therefore, we repeated the search strategy in this present study to provide a more current overview of the state of the science related to perspectives on quality in cancer care from January 2009 through May 2013.

Methods

MEDLINE and PubMed databases were searched systematically for publications related to cancer that were published between January 2009 and May 2013. The PubMed Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) terms that were used in this study include “neoplasms/drug therapy,” “cancer care facilities,” and “oncology service, hospital.” The MeSH terms that were used to capture studies on quality of care are “quality of health care,” “quality assurance, health care,” and “quality indicators, health care.” Additional articles were obtained from the selected article bibliographies and from online searches informed by content from the selected articles.

Each article obtained through the predefined MeSH terms search strategy and hand-searching method was reviewed for eligibility. Articles were eligible for inclusion if they met all the following criteria—(1) the article was focused on adult cancers, (2) quality indicators of cancer care or of quality of care were discussed in the article body, (3) the article discussed chemotherapy treatment for cancer, (4) the study was conducted in the United States and with US respondents, and (5) the article reported data about cancer quality that were obtained directly from various stakeholder groups (ie, patients, caregivers, providers, payers, other healthcare professionals).

An article was ineligible for inclusion if it did not present any perspectives on cancer quality care, if it focused on pediatric oncology, if it was not related to oncology or cancer, or if it did not include perspectives on the chemotherapy treatment period. To be consistent with the previous review by Colosia and colleagues,5 studies were also deemed ineligible if they only addressed quality of survivorship, end-of-life care, supportive care, or hospice care for patients with cancer; if they only addressed quality of preventive or screening services for cancer prevention or early detection; if they addressed quality-of-care delivery methods; if the article had been included in that earlier review5; or if the article type was a review, editorial or letter to the editor, case report, news report, meeting summary report, or a commentary.

The following data were extracted from each eligible article or abstract: type of study, sample size, study population demographics, disease site(s), and survey instruments or questionnaires that were administered. The thematic qualitative data extraction initially focused on the themes within the earlier review by Colosia and colleagues.5 The articles were further culled for emerging themes that were not previously identified and were related to cancer care quality from each perspective. Finally, the qualitative analysis assessed the intersection of quality care issues from the various perspectives.

Results

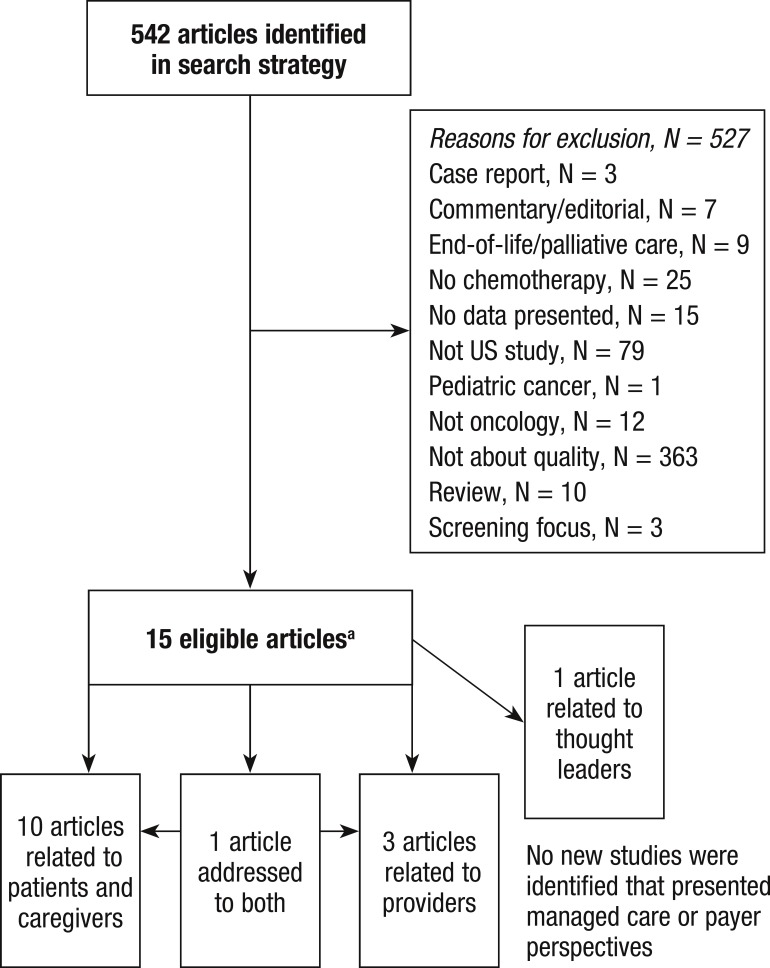

The search strategy identified 542 articles that were reviewed for eligibility (Figure 1, page 323). Of these articles, 15 were eligible for inclusion and reported perspectives from patients, providers, caregivers, and thought leaders (Table 1, page 324).6–20

Figure 1. CONSORT Diagram.

aReferences 6–20.

Table 1.

Eligible Studies: 15 Publications, 4934 Participants

| Study | Stakeholder group(s), N | Study design | Primary objective of study | Data source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Taplin et al, 20107 | Patients, 6 | Retrospective | To understand process of care and quality perspectives | Interview |

| Dulko and Mooney, 20108 | Patients, 92 | Cross-sectional | To understand patient perception of quality care | Survey |

| Scandrett et al, 20109 | Patients, 159 | Pre-/post-design | To compare quality of care with or without intervention | Survey |

| Teno et al, 200910 | Patients, 206 | Longitudinal | To measure quality-of-care concerns of patients | Survey |

| Roundtree et al, 201111 | Patients, 33 | Retrospective | To describe perceptions about care | Focus group |

| Thind et al, 201012 | Patients, 924 | Cross-sectional | To identify factors in satisfaction related to quality care | Survey |

| Lis et al, 201113 | Patients, 2018 | Cross-sectional | To assess the relationship between quality and willingness to recommend | Survey |

| Tsianakas et al, 201214 | Patients, 95 | Cross-sectional | To compare interviews to surveys to understand priorities for quality improvement | Survey/interview |

| Bickell et al, 201215 | Patients, 374 | Longitudinal | To describe perceptions of quality care | Survey |

| Landercasper et al, 201016 | Patients, 234 | Retrospective | To assess relationship between timeliness and patient satisfaction | Survey |

| Wagner et al, 201017 | Patients/caregivers, 39 Providers, 15 | Retrospective | To assess barriers and facilitators to quality care | Focus group |

| Nelson, 201118 | Providers, 20 | Longitudinal | To describe perceptions of staffing for quality care | Interview |

| Bunnell et al, 201319 | Providers, 74 | Pre-/post-design | To measure changes in perceptions of quality care | Survey |

| Burg et al, 201020 | Providers, 622 | Cross-sectional | To describe barriers to quality patient care | Survey |

| Aiello Bowles et al, 20086 | Thought leaders, 23 | Cross-sectional | To assess barriers and facilitators to quality care | Interview |

The primary reasons for article ineligibility included a lack of information on cancer quality (N = 363), data from outside of the United States (N = 79), and not focusing on quality of care during chemotherapy (N = 25).

Of the eligible articles, 10 articles focused solely on the perspectives of patients and caregivers7–16; 3 articles focused on the perspectives of providers18–20; and 1 article covered both perspectives.17 One article presented the perspectives of thought leaders,6 and no new articles were identified that presented the perspectives of managed care or of payers.

Patient Perspectives

Of the eligible articles, 11 included perspectives from 4180 patients with cancer and caregivers.7–17 Of the 5 studies that reported age, the mean age of patients was 55.7 years.9,11,13,15 Five studies were limited to patients with breast cancer,11,12,14–16 5 studies included various tumor types (primarily breast, colon, lung, prostate, cervical, pancreatic, and hematologic malignancies),7–10,13 and 1 study did not provide information on the tumor type of the patients who were included in the study.17

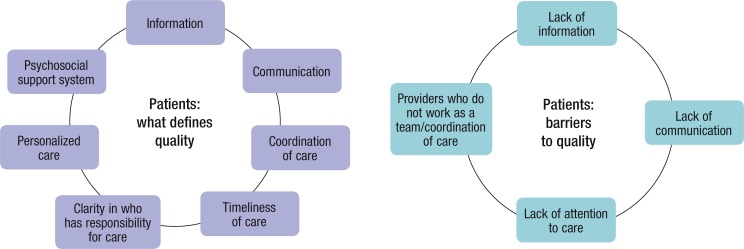

A number of key themes emerged related to the perspectives of patients with cancer regarding quality care (Figure 2, page 324). Examples of content from the eligible articles supporting these themes is provided in Table 2 (page 325).7–17 The themes defining quality care included information for patients, communication between patients and providers, coordination of care, timeliness of care, responsibility for care, personalized care, and psychosocial support. Three of these themes (ie, coordination of care, communication, and information) were also considered barriers to quality care if they were not met, along with the final theme of a lack of attention to care, which was a patient-reported barrier to healthcare quality.7,9–11,14,17

Figure 2. Patient Perspectives of Quality Cancer Care.

Source: References 7–17.

Table 2.

Content of Patient-Reported Cancer Quality Themes

| Patient theme | Content |

|---|---|

| Information |

Defining: help patients and families find reputable websites; navigators to help patients participate in decision-making; knowledge of how to manage side effects; care team helping patient to understand diagnosis; written information on what to expect during treatment, side effects, and what to do at home; knowing who to ask when there are questions Barriers: patients overwhelmed by amount of, complexity of, and conflicts in information; patient education provided after major decisions have been made; lack of awareness of what was going to happen, procedures not explained; not understanding test results; contradictory information; not knowing where to call after hours |

| Communication |

Defining: high ratings of communication correspond to high ratings of quality care Barriers: inaccurate/contradictory information from interactions with providers; understandability of instructions or information given at diagnosis and during treatment decision-making |

| Coordination of care |

Defining: find a “one-stop shopping” approach to cancer care; enhanced role of primary care provider during treatment; all providers working as a team Barriers: lack of teamwork among a variety of healthcare providers; disorganization between providers; lack of single source of information on treatment history, tests, and billing; primary care does not understand cancer and specialist is only familiar with cancer |

| Timeliness of care |

Defining: patients getting a more rapid diagnosis and are more satisfied with care; timely care is in accordance with patient preferences, not just shorter time Barriers: problems with appointment systems or waiting times lead to missed appointments; takes too long to reach a provider when there is an urgent issue; delays during the diagnostic period increased distress; long wait times add to patient stress |

| Responsibility for care | Participatory decision-making associated with greater satisfaction; need to have clarity in who is responsible for which part of care; patients do not want to be left with the responsibility of making sure things are done correctly |

| Personalized care | Being cared for as a person rather than just as a patient; “whole person” approach to care; provider and staff knows you by name; high ratings of treatment by providers associated with willingness to recommend provider |

| Psychosocial support | Need for peer and professional psychosocial support for patients; need for emotional support from the healthcare provider; services need to be introduced earlier in the care plan; social support from family and friends |

| Lack of attention to care | Providers do not pay enough attention to the individual's care; patients have insufficient amount of time with the provider; lack of attention during inpatient stay and lack of respect have an impact on recovery |

Provider Perspectives

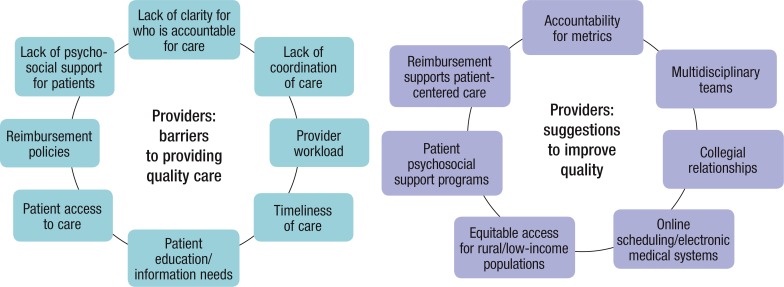

Provider perspectives were obtained from 731 physicians, nurses, social workers, and clinic staff. Their perspectives included recommendations to improve quality, such as accountability for metrics of care, the use of multidisciplinary teams, collegial relationships among the provider team, electronic medical and scheduling systems, equitable access to care, patient psychosocial support programs, and reimbursement programs that support the use of patient-centered care (Figure 3).17–20

Figure 3. Provider Perspectives of Quality Cancer Care.

Source: References 7–17.

Providers noted that barriers to quality care included a lack of clarity regarding who is responsible for the patient's care, lack of coordination of care, provider workload, challenges with the timeliness of care, patient education and information needs, barriers to patient access to care, reimbursement policies, and the lack of psychosocial support programs (Figure 3). Examples of the content that was associated with these themes is summarized in Table 3.17–20

Table 3.

Content of Provider-Reported Cancer Quality Themes

| Provider theme | Content |

|---|---|

| Access to care |

Barrier: racial, ethnic, socioeconomic, and geographic disparities; childcare/eldercare needs; low income and uninsured difficulties in accessing services; inadequate insurance Recommendation: use of telemedicine for rural care; increased linkages between cancer centers and safety net hospitals |

| Reimbursement policies |

Barrier: no reward for services that provide information or supportive care; reimbursement discourages patient-centered care Recommendation: financial incentives/changes in reimbursement that encouraged patient-centered services |

| Lack of psychosocial support services for patients |

Barrier: patients experience fear, anxiety, depression, and distress; lack of systematic assessment of or attention to psychosocial issues Recommendation: enhancing the quality of service provision by hiring more oncology social workers and educating them in cancer care; use of patient navigators to provide support |

| Accountability for care/metrics of care | Lack of clarity in who guides patient care before and after therapy for cancer; integrated cancer care services will help support accountability; published performance measures |

| Coordination of care | Lack of coordination before and after treatment period; multidisciplinary care starts too late, after treatment is already initiated; no clear provider at time of arrival to oncology; difficulty communicating with off-site providers |

| Provider workload | Inadequate staffing leads to alteration, elimination, or delay in patient care and increases concerns about safety; nursing fills in for missing support services, thereby impacting quality care |

| Timeliness of care | Unclear accountability and inadequate staffing contributes to delays in care; care managers could facilitate this |

| Patient education/information | Patient navigators to help them access information; care centers vary widely in emphasis and resources devoted to educating patients; key information provided after major decisions have already been made; provider time to answer patient questions and details needed by patient takes away provider's time for care of the patient |

| Multidisciplinary teams | Multidisciplinary teams can improve the timeliness of care; a barrier when multidisciplinary care begins after the initiation of treatment |

| Collegial relationships | Quality care improves when collegial relationships and good communication exist between nurses and physicians |

| Electronic systems | Electronic systems can improve the timeliness of care; electronic health records and patient portals could inform/connect patients to information and services; shared electronic health records can help coordinate care, facilitate provider communication, support multidisciplinary care planning, and improve safety; online appointment scheduling |

Thought Leader Perspectives

Perspectives were obtained from 23 thought leaders in one study.6 The barriers to quality care noted in this study included a lack of standardization and a lack of adherence to guidelines, difficulty in scheduling appointments, patient out-of-pocket costs, reimbursement policies, a lack of documentation, a lack of teamwork and care coordination, low provider awareness of new research, patient anxiety, and a lack of patient awareness and education.6 Some of the facilitators that were reported to improve quality care included real-world data, shared decision-making, interactive websites, electronic medical records and other information technology innovations, patient navigators and family or social support, outcomes-based performance measures, and risk-adjusted reimbursement policies.6

Discussion

This study has updated an earlier review of perspectives of quality care in cancer, because there have been more recent initiatives and mandates related to quality healthcare.3 In the previous review, 25 sources were identified that reported perspectives of quality care over a 13-year period.5 The current study identified an additional 15 articles that were published within the past 4 years (from 2009 to 2013), representing a much shorter period, which indicates an increasing interest in and focus on the topic of quality cancer care.

Some of the themes emerging from this update are consistent with the earlier review, such as patient information needs, the importance of social support, concerns with coordination of care, provider workload, reimbursement policies, and the need for improved patient interaction and communication with providers. However, new themes emerged in the new publications related to the perspectives of providers, such as accountability for care, the desire for multidisciplinary teams, and collegial relationships among providers to enhance quality care.

There were no perspectives identified in the eligible articles that addressed improved outcomes associated with quality care. However, the ultimate goal of quality cancer care should not only be the short-term improvements in processes, but rather improvements in patient outcomes, such as reduced toxicity resulting from supportive care, fewer hospitalizations as a result of improved healthcare delivery that can help to address concerns before they become serious or life-threatening.

Recent research has demonstrated that adherence to treatment guidelines, such as guidelines published by the NCCN, are associated with improved survival outcomes.21,22 However, quality measures remain largely process-oriented, and there is an expressed need to include additional outcomes-oriented quality measures.23 The relationship between process improvements and outcomes measures has yet to be fully demonstrated, but it may help to address this concern.

The common themes that emerge in this analysis in the 2 most researched stakeholder groups—patients and providers—suggest common perceptions of quality cancer care. Patients, their caregivers, and providers all express the need for better patient information, improvements in care coordination, and for multidisciplinary care that includes psychosocial support and the importance of timeliness of care. In addition, patients desire more personalized care, improved communication with providers, and additional clarity regarding who has responsibility for their care.

Overall, these findings suggest that there may be a need to develop improved initiatives that address patient-provider communication and information sharing, as well as initiatives to provide multidisciplinary care at the point of an initial diagnosis. However, there may also be barriers to these initiatives as noted by providers: their workload and their time are already restricted; there is inequitable access to care among patients (as a result of healthcare disparities, insurance issues, rural location, and out-of-pocket costs); and there is a need for appropriate reimbursement to support patient-centered care.

Limitations

Although the search strategy was designed to be comprehensive, it is possible that additional publications addressing the quality of cancer care were not identified. Although MEDLINE and PubMed databases were searched, there are other sources of information, such as meeting abstracts and organization reports, that were not explored as sources of information for this study.

The summaries and themes cannot necessarily be considered representative of the views of these stakeholder groups, because many of the studies identified in the literature were designed to explore specific concepts, which contributed to the themes that were chosen. There is always the risk of a subjective interpretation of common themes in a qualitative review of the literature.

Although the current study focused on quality care during chemotherapy, to be consistent with the methods of the earlier review,5 there is a need to understand the quality cancer care perspectives in the survivorship community, which is not represented in this present article.

In addition, because 9 articles were identified that focused on end-of-life care and up to 25 other articles that dealt with other treatment or follow-up periods during survivorship, there may be sufficient information to evaluate the perspectives of cancer care for periods of cancer-related care beyond the chemotherapy treatment period. The full trajectory of care throughout the survivorship period is therefore recommended as a topic for future research.

Conclusion

The themes identified in this study may serve as a starting point for initiatives or programs that are designed to improve quality of cancer care and to identify measures associated with factors that are important to patients and to providers. Initiatives that focus on enhancing the quality of cancer care may need to consider the limitations and barriers to care noted in this article, especially regarding the patient–provider communication and information sharing, as well as the need for reimbursement to support patient-centered care. To increase the likelihood of success, such initiatives should include strategies to mitigate these barriers. Future studies are warranted to address the full range of quality care throughout the survivorship period and through end-of-life care, as well as to better understand payer perspectives.

Author Disclosure Statement

Dr Hess is an employee of Eli Lilly and Company. Dr Pohl is an employee of and a stockholder of Eli Lilly and Company.

Contributor Information

Lisa M. Hess, Dr Hess is Principal Research Scientist, US Health Outcomes and Health Technology Assessment, Eli Lilly and Company, Indianapolis, IN, and Adjunct Professor, Schools of Medicine and Public Health, Indiana University, Indianapolis.

Gerhardt Pohl, Dr Pohl is Research Advisor, Statistics, Global Patient Outcomes and Real World Evidence, Eli Lilly and Company, Indianapolis, IN..

References

- 1.Siegel R, Naishadham D, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2013. CA Cancer J Clin. 2013; 63: 11–30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Siegel R, DeSantis C, Virgo K, et al. Cancer treatment and survivorship statistics, 2012. CA Cancer J Clin. 2012; 62: 220–241 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Patel KK, Tran L. Opportunities for oncology in the patient protection and affordable care act. Am Soc Clin Oncol Educ Book. 2013; 2013: 436–440 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Campion FX, Larson LR, Kadlubek PJ, et al. Advancing performance measurement in oncology: quality oncology practice initiative participation and quality outcomes. J Oncol Pract. 2011; 7 (3 suppl): 31S–35S [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Colosia AD, Peltz G, Pohl G, et al. A review and characterization of the various perceptions of quality cancer care. Cancer. 2011; 117: 884–896 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Aiello Bowles EJ, Tuzzio L, Wiese CJ, et al. Understanding high-quality cancer care: a summary of expert perspectives. Cancer. 2008; 112: 934–942 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Taplin SH, Rodgers AB. Toward improving the quality of cancer care: addressing the interfaces of primary and oncology-related subspecialty care. J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr. 2010; 2010: 3–10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dulko D, Mooney K. Effect of an audit and feedback intervention on hospitalized oncology patients' perception of nurse practitioner care. J Nurs Care Qual. 2010; 25: 87–93 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Scandrett KG, Reitschuler-Cross EB, Nelson L, et al. Feasibility and effectiveness of the NEST13+ as a screening tool for advanced illness care needs. J Palliat Med. 2010; 13: 161–169 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Teno JM, Lima JC, Lyons KD. Cancer patient assessment and reports of excellence: reliability and validity of advanced cancer patient perceptions of the quality of care. J Clin Oncol. 2009; 27: 1621–1626 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Roundtree AK, Giordano SH, Price A, Suarez-Almazor ME. Problems in transition and quality of care: perspectives of breast cancer survivors. Support Care Cancer. 2011; 19: 1921–1929 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Thind A, Hoq L, Diamant A, Maly RC. Satisfaction with care among low-income women with breast cancer. J Womens Health (Larchmt). 2010; 19: 77–86 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lis CG, Rodeghier M, Gupta D. The relationship between perceived service quality and patient willingness to recommend at a national oncology hospital network. BMC Health Serv Res. 2011; 11: 46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tsianakas V, Maben J, Wiseman T, et al. Using patients' experiences to identify priorities for quality improvement in breast cancer care: patient narratives, surveys or both? BMC Health Serv Res. 2012; 12: 271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bickell NA, Neuman J, Fei K, et al. Quality of breast cancer care: perception versus practice. J Clin Oncol. 2012; 30: 1791–1795 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Landercasper J, Linebarger JH, Ellis RL, et al. A quality review of the timeliness of breast cancer diagnosis and treatment in an integrated breast center. J Am Coll Surg. 2010; 210: 449–455 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wagner EH, Aiello Bowles EJ, Greene SM, et al. The quality of cancer patient experience: perspectives of patients, family members, providers and experts. Qual Saf Health Care. 2010; 19: 484–489 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nelson BA. Healthcare team members' perception of staffing adequacy in a comprehensive cancer center. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2011; 38: 52–59 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bunnell CA, Gross AH, Weingart SN, et al. High performance teamwork training and systems redesign in outpatient oncology. BMJ Qual Saf. 2013; 22: 405–413 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Burg MA, Zebrack B, Walsh K, et al. Barriers to accessing quality health care for cancer patients: a survey of members of the association of oncology social work. Soc Work Health Care. 2010; 49: 38–52 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Boland GM, Chang GJ, Haynes AB, et al. Association between adherence to National Comprehensive Cancer Network treatment guidelines and improved survival in patients with colon cancer. Cancer. 2013; 119: 1593–1601 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bristow RE, Chang J, Ziogas A, Anton-Culver H. Adherence to treatment guidelines for ovarian cancer as a measure of quality care. Obstet Gynecol. 2013; 121: 1226–1234 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kurian AW, Edge SB. Information technology interventions to improve cancer care quality: a report from the American Society of Clinical Oncology Quality Care Symposium. J Oncol Pract. 2013; 9: 142–144 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]