Abstract

The BDNF is required for the development and proper function of the central nervous system, where it is involved in a variety of neural and molecular events relevant to cognition, learning, and memory processes. Although only a functional mature protein is synthesized, the human BDNF gene possesses an extensive structural complexity, including the presence of multiple promoters, splicing events, and 3´UTR poly-adenylation sites, resulting in an intricate transcriptional regulation and numerous messengers RNA. Recent data support specific cellular roles of these transcripts. Moreover, a central role of epigenetic modifications on the regulation of BDNF gene transcription is also emerging. The present essay aims to summarize the published information on the matter, emphasizing their possible implications in health and disease or in the treatment of different neurologic and psychiatric disorders.

Keywords: BDNF, alternative promoters, transcripts, epigenetic, psychiatric and neurological disorders

Introduction

The Brain-Derived Neurotrophic Factor (BDNF), purified from the porcine brain in 1982 by Barde et al. [1], is member of the neurotrophins (NTs) family, is involved in the development of the vertebrate nervous system (NS) [2,3], and regulates synaptic plasticity in the adult brain, influencing the migration of axons and adjusting the number and size of dendrite spines in neurons [4]. It is also involved in neurogenesis [5] and synaptogenesis [6] and facilitates the physiological mechanism of long-term potentiation (LTP) in hippocampus [7], so it has been associated with processes of learning and memory [8]. In contrast, the immature isoform (proBDNF) has been associated with the activation of neural apoptosis [9] and facilitation of long-term depression in hippocampus [10].

In addition to its neurotrophic function, BDNF strongly promotes cell survival in various animal models of neurological disorders such as the Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis (ALS), Parkinson’s and Alzheimer’s diseases [11], and epilepsy [12]. Moreover, the observation that the in vitro application of some antidepressant drugs increases the levels of BDNF [13] supports a relevant role of this neurotrophin in the patho-physiology of depression [14]. Overall, this leads to consider that failures in the regulation of BDNF synthesis could be related to diverse neurological and psychiatric disorders [15], as well as sustains the proposal of its possible therapeutic use [11-13].

The BDNF possess a structural and functional complexity reflected in 1) the presence of multiple gene promoters; 2) the expression of multiple transcripts, susceptible to alternative splicing events and/or different poly-adenylation patterns; 3) the synthesis of diverse precursor isoforms (pre-pro-BDNF), but only a single mature molecule; 4) the activation of two different receptors regulating opposite effects. In summary, all of these features imply the existence of a very selective molecular mechanism that regulates the proper production of BDNF [16,17].

This review will attempt to summarize the complex BDNF transcription regulation, taking into consideration relevant epigenetic mechanisms. A strong similarity in sequence and gene structure for BDNF among vertebrates is acknowledged; therefore, although some important aspects of the human BDNF gene are still unknown, inferences can be obtained from other species. For instance, the BDNF 5´ exon sequence identity among the human (Homo sapiens), rodent (Rattus norvegicus, Mus musculus), and fish (Dicentrarchus labrax) ranges from 95 percent to 38 percent, with the exon II showing the highest value (≈90%) [18]. In the same way, exon I, IV, and VI are quite similar when rodents and humans are compared [15]. Moreover, they share the same alternative 5´ exon splicing mechanism [15,18].

We will also attempt to discuss the putative implication of these molecular events to health and disease. Other important cellular processes involved in the proper function of the mature protein as the regulation of post-translational modifications or the constitutive or regulated secretion will not be covered here.

Human BDNF Gene Structure

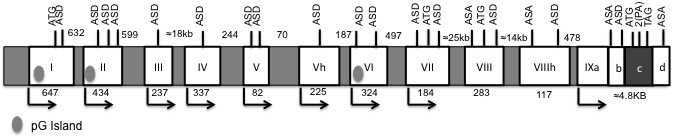

The human BDNF gene is located at chromosome 11, region p13-14. The current expert agreement indicates the existence of 11 exons (Figure 1), nine of which contain a specific promoter that regulates its expression [17,19]. Although the use of alternative promoters is not uncommon (i.e., the presence of two to three promoters has been described in approximately 50 percent of the human genes [20]), the existence of nine different promoter sequences is an exceptional characteristic of the BDNF gene. Moreover, the intron-exon boundaries possess the archetypical GU-AG consensus signals for alternative splicing events [19-21].

Figure 1.

BDNF human gene structure. The white boxes indicate exons, the numbers below show the base pairs that comprise them. The grey spaces point to introns, and the numbers above the base pair that constitute them. The arrows designate the alternative start transcription sites. ASD represents Alternative Splicing donors, while ASA represents Alternative Splicing acceptor sites; the ATG symbols indicate start translation codons. The PA inscription correspond to alternative poly-adenylation sites, and the TAG mark designates the only termination codon for translation within this gene. It is important to point out that the 5’ regions of exon I, II, III, IV, V, Vh, VI, VII, and IX correspond to independent promoters that regulate the expression of at least 17 transcripts and that exon I, II, and VI present CpG islands that in this figure are marked by ovals. Finally, the region c of exon IX marked with dark grey corresponds to the codification region of proBDNF.

Additionally, an interesting but frequently ignored feature of the structure of the BDNF gene is the existence of a 200 kb antisense region that includes 10 exons transcribed from a single promoter [22] with the ability to synthesize a wide variety of anti-BDNF small non-coding RNAs (miRNAs) [17,19,20].

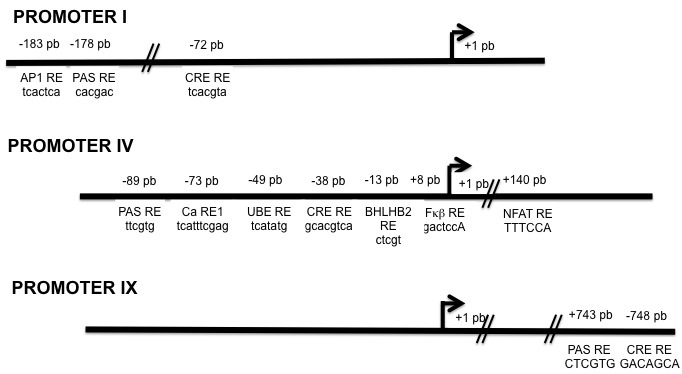

As illustrated in Figure 2, a number of DNA binding sites for distinct transcription factors have been characterized in the different promoters of the rodent BDNF gene [23-26]. Interestingly, an increase in intracellular calcium (Ca++) levels has been associated with the activation of these binding sites [27,28]. This is relevant because it has been described that either the activation of glutamate receptors or voltage-gated calcium channels (VGCC) promotes the differential expression of particular BDNF transcripts [29,30]. Intriguingly, in cultured primary neurons obtained from a transgenic mice to which the human BDNF gene was inserted, the Calcium Response Element (CaRE), the Nuclear Factor Activated T cells Response Element (NFATRE), and the Nuclear Factor κβ Response Element (NFκβRE) [19] ― activated by an influx of Ca++ in the rodent BDNF gene after the glutamate receptor stimulation [31-34] ― showed otherwise to be insensitive to the neural depolarization elicited by the activation of L-type VGCC [19]. These results underscore the notion that the involvement of specific intracellular second messenger pathways (activated by intracellular Ca++) dictates the expression of different BDNF transcripts, possibly via the synthesis and binding of different transcription factors to a particular promoter sequence [35].

Figure 2.

Structure of the human BDNF promoters pI, pIV, and pIX. Describes the transcription factors that in vitro studies have demonstrated that can join this gene. The arrows correspond to the site where the start transcription codon is located. The numbers above the line indicate the base pairs where the consensus regions for each transcription factor were identified. The legends below the line specify the transcription factor that binds to that locus and the sequence of nucleotides important for that. Abbreviations: AP1 RE: Adaptor Protein 1 Response Element; Pas RE: Pas Response Element with a reverse direction; CRE RE: cAMP/Ca++ Response Element; Ca RE1: Calcium Response Element type 1; UBE RE: Upstream Stimulatory Factor Binding Response Element; bHLHB2 RE: Basic Helix Loop Helix B2 Response Element; NFκβ RE: Nuclear Factor κβ Response Element; NFAT RE: Nuclear Factor of Activated T cells Response Element.

Moreover, the preferential activation of certain promoters could have a significant role in the susceptibility of developing certain neurological or psychiatric disorders [15,22], as exemplified in reports on depression [36], bipolar disorder [37], schizophrenia [37,38], epilepsy [39], and Alzheimer’s disease [40], where changes in the BDNF expression have been described.

Epigenetic Regulation of BDNF

Other molecular events involved in the regulation of BDNF expression are those related to the epigenetic modifications. In a broad sense, epigenetics refers to the way in which chromatin structure is remodeled without affecting the sequence of nucleotides within the DNA. For many years, these processes were only implicated in cellular differentiation and development; however, it is currently recognized that they are also relevant for differentiated cells [41-44]. A case in point are neurons in which the cell plasticity, necessary for processes of learning and memory, needs to be long-lasting or permanent; therefore, epigenetic mechanisms could help to explain, for example, why neurons do not actively divide [45].

Experimental results obtained from in vitro and animal models support the role of epigenetics mechanisms on the regulation of BDNF gene expression. For instance, the in silico analysis of the gene sequence shows a number of CpG islands in promoters (p) pI, pII and pIV of the human gene and pI, pII, pIV, pV, pVI, and pIX in the rodent gene [16]. Moreover, the treatment with the DNA methyl inhibitor 5-azacitidyne (5azadC) stimulates the expression of exons I, IV, V, VIII, and IX in C6 rat glioma cells and exons I, III [15] and IV [46] in mouse neuroblastoma cells (Neuro2A). On the other hand, addition of the histone deacetylase inhibitor Trichostatin A (TSA) promotes an increased expression of exons III, VII, and VIII in C6 cells, although it did not affect the expression of any transcript in Neuro2A cells [15]. Nonetheless, in the latter example, an increment in the expression of exon I and IV was detected when higher concentrations of TSA were used, an outcome also linked with an increase in Histone (H) 3 and H4 acetylation in the BDNF pI, an epigenetic mark linked with gene expression [46]. Interestingly, in the latter study , the highly methylated status of the 5’ proximal region of the BDNF exon I — but not the exon IV — observed under basal conditions disappears after treatment with 5AzadC [46]. As a whole, these results suggest that there must be an extremely specific epigenetic regulation of BDNF expression regarding promoters and cell types.

On the other hand, several molecules participate in the epigenetic regulation of BDNF. One example is the methyl-CpG binding protein 2 (MeCP2), identified by its ability to add methyl groups in the genome [47] and for recruiting the type I histone deacetylase (HDAC1) Sin3A [48]. It was recently described in cultured mouse cortical neurons that the MeCP2-Sin3A complex generates a long-term inhibition of the BDNF pIV [49]. Moreover, the experimental observation of the phosphorylation and further dissociation of MeCP2 from this locus, either after depolarization of cultured rat neurons [28,49,50] or following the activation of the cyclic adenosin monophosphate (AMPc) pathway in the human neuroblastoma cells [51], support a relevant role of MeCP2 in the regulation of BDNF gene expression.

Another relevant instance is the growth arrest and DNA damage-inducible 45B protein (Gaad45B) involved in the demethylation of neurogenesis-related genes [44,52]. This molecule binds to pIX of the rat gene, promoting hippocampal neurogenesis [44,53]. Additional germane examples with a putative epigenetic effect over this neurotropin are 1) the transcription factor NFκβ, since a di-methylation of lysine 4 residue at H3 histone on the BDNF pI has been detected in a locus containing a potential NFκβ binding site [54]; and 2) the CREB binding protein (CBP), which adds acetyl groups to histones in other gene sequences (like the Major Histocompatibility Complex class II gene) [55,56]. It is known that CREB binds to different BDNF promoters (Figure 2) [19,23], although it remains to be demonstrated that the complex CREB/CBP can acetylate histones at BDNF specific loci.

Lastly, the anti-BDNF transcripts (miRNAs) may also have the potential to regulate the expression of this neurotrophin through epigenetic mechanisms. For instance, in vitro studies show that these molecules can diminish both the expression of mRNA and synthesis of the protein through the recruitment of EZH2, a methyl-transferase promoting the three-methylation of lysine 27 residue at H3 on the BDNF locus, an epigenetic mark frequently linked with repression of transcription [20]. Moreover, the genetically engineered over-expression of miRNA 212 in the rat striatum decreases the BDNF protein levels through deactivation of MeCP2 [57]. However, no changes were observed in the expression of BDNF after exposure to an enrichment environment in which an increment of mir124, mir132, mir133, and mir14 were also noted [58].

It is worth to note that epigenetic marks in different promoters of the murine BDNF gene have been described in relation to several “external/environmental” events like consumption of cocaine, stress in the early stages of life, memory related to fear, voluntary exercise, and enriched environment [16], as well as after psychopharmacological manipulation (Table 1) [59-62]. Remarkably, in some of these studies, there is a significant correlation among specific histone modification, DNA methylation patterns at pI, pIV, and pVI, and changes in the expression of the correspondent transcripts [61-63]. Unfortunately, changes in epigenetic marks related to neuropsychiatric disorders has been analyzed only recently in a limited number of studies (Table 2) [64-74].

Table 1. Epigenetic effects of the pharmacological treatment for neuropsychiatric disorders.

| Reference | Treatment | Model | mRNA BDNF | Epigenetic | Brain region |

| [59] | Fluoxetine | Perinatal stress in rats | ⇑ | ⇑ H3 acetylation in pIV | Hippocampus |

| [60] | Imipramine | Social defeated mice | ⇑ | ⇑ H3 acetylation in pIV and pVI and H3K9 methylation in pIII | Hippocampus |

| [61] | Valproic acid | Fear conditioning rats | ⇑ IV | ⇑ H3 acetylation in pIV | Prefrontal cortex |

| [62] | In Vitro | ⇑ I and IV | ⇑ H3 and H4 acetylation in pI and H4 acetylation in pIV | Rat cortical neurons |

Table 2. Epigenetic modification in BDNF human gene.

| Reference | Study Subjects | Variable | BDNF | Epigenetic Changes | Tissue | Sample Status |

| [64] | Schizophrenia | BDNF Val66Met SNP | ⇓ Methylation at exon IX | Frontal cortex | Post-mortem | |

| [65] | Suicide victims | Suicide death | ⇓ mRNA and protein | ⇑ Methylation at pIV | Wernicke Area | Post-mortem |

| [66] | Healthy adolescents | Smoking during pregnancy | ⇑ Methylation at pVI, but no at pIV | Peripheral blood | In vivo | |

| [67] | Mother | Prenatal maternal depression | Any effect | Peripheral blood and umbilical cord | In vivo | |

| [68] | Depression | Antidepressant treatment | ⇑ mRNA | ⇓ H3K27me3 at pIV | Frontal cortex | Post-mortem |

| [69] | Alzheimer and bipolar disease | Cases vs. controls | ⇓ mRNA | ⇑ Methylation | Frontal cortex | Post-mortem |

| [70] | Bipolar disorder | Cases vs. controls | ⇓ mRNA | ⇑ Methylation at p1 | Peripheral blood | In vivo |

| [71] | Schizophrenia | Cases vs. controls | ⇓ mRNA | ⇓ Methylation | Peripheral blood | In vivo |

| [72] | Bipolar disorder | Cases vs. controls | ⇑ protein but not associated with methylation status | ⇑ Methylation at pI and exon IV | Peripheral blood | In vivo |

| [73] | Post-stroke depression | Presence of depression | ⇓ Methylation | Peripheral blood | In vivo | |

| [74] | Major depression disorder | Antidepressant treatment | ⇓ protein (non significant) | ⇓ Methylation at pIV in non-responders | Peripheral blood | In vivo |

Transcriptional Regulation of BDNF

As result of the existence of multiple promoters and alternative splicing events, at least 17 transcripts with different 5′ and 3′UTR (untranslated region) segments could be synthesized from the BDNF human gene [17]. Nonetheless, all these messengers share a common coding region included in exon IX that comprises the complete sequence of the proBDNF molecule. Additionally, this exon contains two poly-adenylation sites generating transcripts with either a long or a short 3’ UTR [17]. The putative functional relevance of this structural feature is revealed by animal model studies showing that mRNAs with a long 3’ UTR are primarily located in dendritic spines [75] and only translated in response to neuronal activation. In contrast, those with a short 3’UTR are actively translated in the soma to maintain the protein BDNF basal levels [76].

Furthermore, a preferential location of specific transcripts, in particular cellular compartments, has been described. For example, in the rodent visual cortex and hippocampus, the messengers from exons I and IV are predominantly expressed near the neural soma, whereas those generated from exons II and VI are mainly located in distal dendrites [77-79]. Interestingly, the aforementioned transcriptional compartmentalization appears to have functional consequences, as indicated by recent in vitro experiments in which the over expression or silencing of these specific BDNF 5´splice variants affect in a spatial fashion the dendritic branching and phosphorylation of the BDNF Tyrosine Kinase B (TrKB) receptor. These experimental data also suggest that the different splice variants could represent a spatial code used by neurons to target the effects of BDNF to distinct neural compartments [80].

Finally, although the BDNF expression along the ontogeny of the brain has been described elsewhere [81,82], the analysis of the different transcripts has been barely addressed. For instance, Pattabiraman et al. [77] noted a pattern of differential expression in the rat visual cortex of various splicing forms at different postnatal days (P). In this brain area, exons IV and VI were noticeable at P13 (a developmental early period linked with the start of eye opening), while exons I and II were detected only until P40 (a mature stage of this sensory cortex and where monocular deprivation has no effect). Moreover, an important increase in the expression of exons IV, and in lesser extent, exon VI, is observed, an effect that remains stable throughout adulthood (P90). Interestingly, it was also found that the expression of exons II, IV, and VI were importantly reduced at P40 in the occipital cortex, as a consequence of temporary blocking the electrical activity of retinal ganglion cells, suggesting a link between the rat visual experience and the BDNF gene transcription during the critical period of formation of ocular dominance columns in the Visual Cortex [83,84]. Unfortunately, an equivalent developmental event in the human visual cortex has not been yet described.

On the other hand, the developmental BDNF expression in the human Dorsolateral Prefrontal Cortex was recently reported [85]. In this cortical region, exons I and VI were steadily expressed throughout the first phases of infancy (neonate, infant, toddler) but decline in the following years (6 to 40 years). In contrast, transcripts II and IV, barely detected in neonates, increased their expression in infants and toddlers to finally diminish and reach a steady level from 5 years through adolescence and adulthood. These data show important brain regional and temporal variation in BDNF expression and important differences among species.

Another putative implication of the expression of this neurotrophin during development was recently discussed by Calabrese et al. [86], who reported that compared to wild type animals, SERT (serotonin transporter) knockout rats displayed a reduced expression of BDNF transcrits I, IV, VI in ventral hippocampus and prefrontal cortex 1 to 4 weeks after birth. The simultaneous decrease of both SERT and BDNF in these animals seems to explain the evident signs of depression and anxiety observed in these genetically modified animals [87], probably affecting neural plasticity. Moreover, it is tempting to assume that changes at critical time windows of development of the expression of this neurotrophin can increase the risk for mood/anxiety, particularly in those individual carrying certain genetic variants of the SERT [86].

In summary, there is solid experimental evidence of the existence of multiple BDNF transcripts with apparently distinct functional properties. Further studies are encouraged, as the accurate time and spatial description of the splice variants might provide key information about the particular cell types or neuronal circuits involved in specific neuropsychiatric disorders, also stimulating the development of alternative pharmacological treatments [80]. Regrettably, only few studies have determined the expression of more than a single transcript at once (Table 3) [88-90].

Table 3. Changes in BDNF transcript expression in humans.

| Reference | Variables | Changes in BDNF transcript expression | Tissue | Samples status |

| [88] | Alzheimer's | ⇓ I, II and IV | Parietal Cortex | Post-mortem |

| [89] | Cocaine Addiction | ⇓ I and IV | Cortex | Post-mortem |

| [89] | Cocaine Addiction | ⇓ IV | Cerebellum | Post-mortem |

| [90] | Schizophrenia | ⇓ II | Frontal Cortex | Post-mortem |

| [90] | Antidepressant Treatment | ⇓ I, II, IV and VI | Frontal Cortex | Post-mortem |

| [90] | Antidepressant Treatment | ⇓ I and II | Parietal Cortex | Post-mortem |

| [90] | Antidepressant Treatment | ⇓ IV | Hippocampus | Post-mortem |

Post-Translational Modifications and BDNF Isoforms

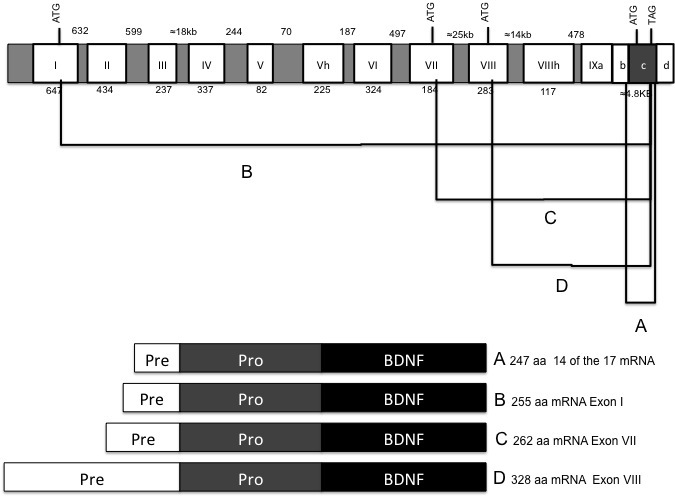

As illustrated in Figure 3, exons I, VII, VIII, and IX possess an alternative translation start codon, but only exon IX includes a translation stop codon. Therefore, theoretically, four different pre-pro-BDNF protein isoforms could be synthesized differing in an extended amino terminal region according to the particular transcribed exon (exon I, VI, and VIII: 8, 15 and 81 amino acids, respectively) [17]. It has been proposed that the length of the pre-domain could affect the intracellular BDNF trafficking, with the longer versions preferentially promoting the secretion of the immature isoform [15].

Figure 3.

BDNF protein products. Shows the protein isoforms that can be synthesized from the BDNF gene and the transcripts that give them origin.

In the brain, the 32 kDa proBDNF can experience at least three final paths: 1) to be edited mainly in Golgi and secreted as the mature BDNF molecule; 2) to be secreted as proBDNF and procesed to mature BDNF in the synaptic space; or 3) to be secreted as proBDNF without any subsequent digestion [91]. In any case, the proper understanding of the different mechanisms and circumstances associated with the neurotrophin secretion will be of great biological relevance as the fine-tuned equilibrium between the different isoforms could dictate different physiological outputs.

ProBDNF binds to the receptor p75 (a member of the tumor necrosis factor receptor family). This binding has been associated with the boosting of long-term depression in neurons of the hippocampus [10] and neuronal pruning in the nervous system [92] or with initiating programmed neuronal death [93]. Similar effects have also been reported when proBDNF binds to the hetero-dimeric p75/sortilin receptor [94]. Moreover, the p75 receptor can also be associated with the Nogo receptor complex (NogoR, Lingo, p75NTR) that mediates inhibition of axon growth [95]. In any case, the binding of proBDNF to p75 activates the Jun kinase signal cascade pathway (JNK), more specifically triggering JNK3 [93], causing apoptosis through the activation of p53 tumor suppressor gene and caspases [95]. Moreover, proBDNF/p75 also activates the small GTPase RhoA and its downstream effector Rho Kinase that has been associated to inhibition of neurite outgrowth [96].

On the other hand, the mature BDNF molecule has an important affinity for TrKB (Kd = 9.9 × 10−10 M) [97]. Binding to this membrane receptor has been related to the increase of synaptic transmission and plasticity, neural proliferation and survival, and axonal sprouting [91,92]. In the absence of TrKB, mature BDNF could also bind to p75 receptor in order to regulate axon pruning [91,92]. The BDNF/TrKB interaction leads to the activation of three intracellular signaling cascades: 1) the phospholipase C; 2) the phosphatidyl-inositol-3 phosphate kinase (PI3K); or 3) the kinases regulated by extracellular signals. These mechanisms promote calcium entrance into the cell that leads to an increment in gene expression, associated with cellular differentiation [8] and dendrite formation [98]. Moreover, TrKB activation stimulates AKT signaling pathway through PI3K to modulate cell survival [99,100].

As previously mentioned, the transcripts with a long 3’UTR are located mainly to distal dendrite. This could largely lead to the secretion of the proBDNF molecule, as this neural compartment does not possess Golgi [75]. Remarkably, in the fish Dicentrarchus labrax, the differential expression of BDNF transcripts after stress can produce an increment in the secretion of proBDNF [18]. To our knowledge, no single study has evaluated if the differential expression of BDNF transcripts could affect the proportion of which proBDNF and BDNF isoforms are secreted in the human brain, information that could have important implications for neuropsychiatric disorders.

Conclusion

As revealed by the increasing number and variety of papers in recent years related to a very broad spectrum of BNDF-associated topics, including health, disease, neuroscience, or cognition, this neurotrophin has become a paradigmatic example of a “multitask” neural molecule.

More specifically, the multiple neural functions associated with its effects in the nervous system have foreseen certain therapeutic applications for a variety of neurological and psychiatric disorders, including ALS, epilepsy, depression, Parkinson’s, and Alzheimer’s disease [11,12,14,101]. Of special interest is the case of ALS, where the administration of BDNF (and other neurotrophins) has been already evaluated in humans. Although the preclinical studies appeared promising, phase III trials showed only minimal beneficial effects for a subgroup patients (e.g., those in an advanced stage of the disease) [101], a failure probably related to the complex regulation of BDNF within the nervous system.

Moreover, the recent description of an accurate distinction between patients with major depression or healthy controls, based on the methylation profiles of CpG units within the BDNF pI in peripheral samples (e.g., leucocytes, blood mononuclear cells), envisage its putative use as an efficient diagnostic biomarker of depression [102].

This approach has been recently attempted for other psychiatric conditions such as schizophrenia [71], borderline personality disorder (BPD) [72], depression after a stroke event [73], and bipolar disorder [70], or as a surrogate marker of clinical response for psychopharmacological response in depression [74,102] or psychotherapy in BPD [72]. Interestingly, in the latter example, the methylation status of BDNF was positively associated with the history of child maltreatment [72], showing that this neurotrophin is an important modulator of the gene/environment interplay, as we have previously reported by evaluating the genetic variance of BDNF in depressive patients [103].

As it has been highlighted in this review, the functional effects of this molecule in a particular brain region would depend on multiple time/location-regulated molecular events, including the synthesis of their different transcripts; the presence of specific transcription factors; the recruitment of molecules with epigenetic effects; and the activation of particular receptors; among others. Moreover, epigenetic mechanisms that seem to be strongly dependent on external/environmental events must be included in this complex molecular equation. This is particularly important to neuropsychiatry stimulating new avenues for clinical experimentation (e.g., by using methylation/acetylation histones-modifying drugs) as currently attempted in cancer treatment.

In any case, further investigation at clinical and basic levels of BDNF production is warranted.

Acknowledgments

This review article constitutes a partial requisite to obtain the PhD grade in the postgraduate program of Biological Sciences at the National Autonomous University of Mexico (UNAM) for GAM-L.

Abbreviations

- BDNF

brain-derived neurotrophic factor

- NT

neurotrophin

- NS

nervous system

- LTP

long-term potentiation

- proBDNF

BDNF immature isoform

- ALS

Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis

- pre-pro-BDNF

precursors of proBDNF

- p

promoter

- miRNAS

small non-coding RNAS

- Ca++

calcium

- VGCC

voltage gated calcium channels

- AP1RE

Adaptor Protein 1 Response Element

- PasRE

Pas Response element with a reverse direction

- CRERE

AMPc/Ca++ Response Element

- CaRE

calcium response element type 1

- UBERE

Upstream Stimulatory Factor Binding Response Element

- bHLHB2RE

Basic Helix Loop Helix B2 Response Element

- NFκβRE

Nuclear Factor κβ Response Element

- NFATRE

Nuclear Factor of Activated T cells Response Element

- 5azadC

5-azacitidyne

- Neuro2A

mouse neural crest-derived cell 2A

- TSA

Trichostatin A

- H

Histone

- MeCP2

methyl-CpG binding protein 2

- HDAC1

Type I histone deacetylase

- AMPc

cyclic Adenosin monophospohate

- Gaad45B

DNA-damage-inducible 45B protein

- CBP

CREB binding protein

- UTR

untranslated region

- TrKB

Tyrosine kinase receptor B

- P

postnatal day

- SERT

serotonin transporter

- JNK

Jun Kinase

- PI3PK

phosphatidyl-inositol-3 phosphate kinase

- BPD

borderline personality disorder

Author contributions

GAML: Search of bibliography; review, summary and discussion of the information, draft of the work; CSCF: Discussion of the reviewed information, evaluation and comments of the draft.

References

- Barde YA, Edgar D, Thoenen H. Purification of a new neurotrophic factor from mammalian brain. EMBO J. 1982;1(5):549–553. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1982.tb01207.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Binder DK, Scharfman HE. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor. Growth Factors. 2004;22(3):123–131. doi: 10.1080/08977190410001723308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chao MV, Rajagopal R, Lee FS. Neurotrophin signaling in health and disease. Clin Sci (Lond) 2006;110(2):167–173. doi: 10.1042/CS20050163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tongiorgi E. Activity-dependent expression of brain-derived neurotrophic factor in dendrites: facts and open questions. Neurosci Res. 2008;61(4):335–346. doi: 10.1016/j.neures.2008.04.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee E, Son H. Adult hippocampal neurogenesis and related neurotrophic factors. BMB Rep. 2009;42(5):239–244. doi: 10.5483/bmbrep.2009.42.5.239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alsina B, Vu T, Cohen-Cory S. Visualizing synapse formation in arborizing optic axons in vivo: dynamics and modulation by BDNF. Nat Neurosci. 2001;4(11):1093–1101. doi: 10.1038/nn735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mei F, Nagappan G, Ke Y, Sacktor TC, Lu B. BDNF facilitates L-LTP maintenance in the absence of protein synthesis through PKMζ. PLoS One. 2011;6(6):e21568. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0021568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cunha C, Brambilla R, Thomas KL. A simple role for BDNF in learning and memory? Front Mol Neurosci. 2010;3:1. doi: 10.3389/neuro.02.001.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teng HK, Teng KK, Lee R, Wright S, Tevar S, Almeida RD. et al. ProBDNF induces neuronal apoptosis via activation of a receptor complex of p75NTR and sortilin. J Neurosci. 2005;25(22):5455–5463. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5123-04.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woo NH, Teng KK, Siao CJ, Chiaruttini C, Pang PT, Milner TA. et al. Activation of p75NTR by proBDNF facilitates hippocampal long-term depression. Nat Neurosci. 2005;8(8):1069–1077. doi: 10.1038/nn1510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagahara AH, Tuszynski MH. Potential therapeutic uses of BDNF in neurological and psychiatric disorders. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2011;10(3):209–219. doi: 10.1038/nrd3366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simonato M, Zucchini S. Are the neurotrophic factors a suitable therapeutic target for the prevention of epileptogenesis? Epilepsia. 2010;51(Suppl 3):48–51. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2010.02609.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nibuya M, Morinobu S, Duman RS. Regulation of BDNF and trkB mRNA in rat brain by chronic electroconvulsive seizure and antidepressant drug treatments. J Neurosci. 1995;15(11):7539–7547. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.15-11-07539.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castrén E, Rantamäki T. The role of BDNF and its receptors in depression and antidepressant drug action: Reactivation of developmental plasticity. Dev Neurobiol. 2010;70(5):289–297. doi: 10.1002/dneu.20758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aid T, Kazantseva A, Piirsoo M, Palm K, Timmusk T. Mouse and rat BDNF gene structure and expression revisited. J Neurosci Res. 2007;85(3):525–535. doi: 10.1002/jnr.21139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boulle F, Van den Hove DL, Jakob SB, Rutten BP, Hamon M, Van Os J. et al. Epigenetic regulation of the BDNF gene: implications for psychiatric disorders. Mol Psychiatry. 2011;17(6):584–596. doi: 10.1038/mp.2011.107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pruunsild P, Kazantseva A, Aid T, Palm K, Timmusk T. Dissecting the human BDNF locus: bidirectional transcription, complex splicing, and multiple promoters. Genomics. 2007;90(3):397–406. doi: 10.1016/j.ygeno.2007.05.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tognoli C, Rossi F, Di Cola F, Baj G, Tongiorgi E, Terova G. et al. Acute stress alters transcript expression pattern and reduces processing of proBDNF to mature BDNF in Dicentrarchus labrax. BMC Neurosci. 2010;14(11):4. doi: 10.1186/1471-2202-11-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pruunsild P, Sepp M, Orav E, Koppel I, Timmusk T. Identification of cis-elements and transcription factors regulating neuronal activity-dependent transcription of human BDNF gene. J Neurosci. 2011;31(9):3295–3308. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4540-10.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimura K, Wakamatsu A, Suzuki Y, Ota T, Nishikawa T, Yamashita R. et al. Diversification of transcriptional modulation: large-scale identification and characterization of putative alternative promoters of human genes. Genome Res. 2006;16(1):55–65. doi: 10.1101/gr.4039406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Modarresi F, Faghihi MA, Lopez-Toledano MA, Fatemi RP, Magistri M, Brothers SP. et al. Inhibition of natural antisense transcripts in vivo results in gene-specific transcriptional up regulation. Nat Biotechnol. 2012;30(5):453–459. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davuluri RV, Suzuki Y, Sugano S, Plass C, Huang TH. The functional consequences of alternative promoter use in mammalian genomes. Trends Genet. 2008;24(4):167–177. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2008.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tao X, Finkbeiner S, Arnold DB, Shaywitz AJ, Greenberg ME. Ca2+ influx regulates BDNF transcription by a CREB family transcription factor-dependent mechanism. Neuron. 1998;20(4):709–726. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)81010-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Timmusk T, Palm K, Lendahl U, Metsis M. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor expression in vivo is under the control of neuron-restrictive silencer element. J Biol Chem. 1999;274(2):1078–1084. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tabuchi A, Sakaya H, Kisukeda T, Fushiki H, Tsuda M. Involvement of an upstream stimulatory factor as well as cAMP-responsive element-binding protein in the activation of brain-derived neurotrophic factor gene promoter I. J Biol Chem. 2002;277(39):35920–35931. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M204784200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tao S, West AE, Chen WG, Corfas G, Greenberg ME. A calcium-responsive transcription factor, CaRF that regulates neuronal activity-dependent expression of BDNF. Neuron. 2002;33(3):383–395. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(01)00561-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marmigère F, Rage F, Tapia-Arancibia L. Regulation of brain-derived neurotrophic factor transcripts by neuronal activation in rat hypothalamic neurons. J Neurosci Res. 2001;66(3):377–389. doi: 10.1002/jnr.1230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- West AE, Chen WG, Dalva MB, Dolmetsch RE, Kornhauser JM, Shaywitz AJ. et al. Calcium regulation of neuronal gene expression. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98(20):11024–11031. doi: 10.1073/pnas.191352298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mellstrom B, Torres B, Link WA, Naranjo JR. The BDNF gene: exemplifying complexity in Ca2+ -dependent gene expression. Crit Rev Neurobiol. 2004;16(1-2):43–49. doi: 10.1615/critrevneurobiol.v16.i12.40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Timmusk T, Palm K, Metsis M, Reintam T, Paalme V, Saarma M. et al. Multiple promoters direct tissue-specific expression of the rat BDNF gene. Neuron. 1993;10(3):475–489. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(93)90335-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen WG, Chang Q, Lin Y, Meissner A, West AE, Griffith EC. et al. Derepression of BDNF transcription involves calcium-dependent phosphorylation of MeCP2. Science. 2003;302(5646):885–889. doi: 10.1126/science.1086446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang X, Tian F, Du Y, Copeland NG, Jenkins NA, Tessarollo L. et al. BHLHB2 controls Bdnf promoter 4 activity and neuronal excitability. J Neurosci. 2008;28(5):1118–1130. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2262-07.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vashishta A, Habas A, Pruunsild P, Zheng JJ, Timmusk T, Hetman M. Nuclear factor of activated T-cells isoform c4 (NFATc4/NFAT3) as a mediator of antiapoptotic transcription in NMDA receptor-stimulated cortical neurons. J Neurosci. 2009;29(48):15331–15340. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4873-09.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quadrato G, Benevento M, Alber S, Jacob C, Floriddia EM, Nguyen T. et al. Nuclear factor of activated T cells (NFATc4) is required for BDNF-dependent survival of adult-born neurons and spatial memory formation in the hippocampus. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109(23):E1499–E1508. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1202068109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng F, Zhou X, Luo Y, Xiao X, Wayman G, Wang H. Regulation of brain-derived neurotrophic factor exon IV transcription through calcium responsive elements in cortical neurons. PLoS One. 2011;6(12):e28441. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0028441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otsuki K, Uchida S, Watanuki T, Wakabayashi Y, Fujimoto M, Matsubara T. et al. Altered expression of neurotrophic factors in patients with major depression. J Psychiatr Res. 2008;42(14):1145–1153. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2008.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson RM, Weickert CS, Wyatt E, Webster MJ. Decreased BDNF, trkB-TK+ and GAD67 mRNA expression in the hippocampus of individuals with schizophrenia and mood disorders. J Psychiatry Neurosci. 2011;36(3):195–203. doi: 10.1503/jpn.100048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paz RD, Andreasen NC, Daoud SZ, Conley R, Roberts R, Bustillo J. et al. Increased expression of activity-dependent genes in cerebellar glutamatergic neurons of patients with schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163(10):1829–1831. doi: 10.1176/ajp.2006.163.10.1829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray KD, Isackson PJ, Eskin TA, King MA, Montesinos SP, BuAbrahamstillo LA. et al. mRNA expression for brain-derived neurotrophic factor and type II calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase in the hippocampus of patients with intractable temporal lobe epilepsy. J Comp Neurol. 2000;418(4):411–422. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-9861(20000320)418:4<411::aid-cne4>3.0.co;2-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holsinger RM, Schnarr J, Henry P, Castelo VT, Fahnestock M. Quantitation of BDNF mRNA in human parietal cortex by competitive reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction: decreased levels in Alzheimer's disease. Brain Res Mol Brain Res. 2000;76(2):347–354. doi: 10.1016/s0169-328x(00)00023-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egger G, Liang G, Aparicio A, Jones PA. Epigenetics in human disease and prospects for epigenetic therapy. Nature. 2004;429(6990):457–463. doi: 10.1038/nature02625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinhold B. Epigenetics: the science of change. Environ Health Perspect. 2006;114(3):A160–A167. doi: 10.1289/ehp.114-a160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldberg AD, Allis CD, Bernstein E. Epigenetics: a landscape takes shape. Cell. 2007;128(4):635–638. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma DK, Jang MH, Guo JU, Kitabatake Y, Chang ML, Pow-Anpongkul N. et al. Neuronal activity induced Gadd45b promotes epigenetics DNA demethylation and adult neurogenesis. Science. 2009;32(5917):1074–1077. doi: 10.1126/science.1166859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Day JJ, Sweatt JD. Epigenetic mechanisms in cognition. Neuron. 2011;70(5):813–829. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2011.05.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishimaru N, Fukuchi M, Hirai A, Chiba Y, Tamura T, Takahashi N. et al. Differential epigenetic regulation of BDNF and NT-3 genes by trichostatin A and 5-aza-2'-deoxycytidine in Neuro-2a cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2010;394(1):173–177. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2010.02.139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nan X, Campoy FJ, Bird A. MeCP2 is a transcriptional repressor with abundant binding sites in genomic chromatin. Cell. 1997;88:471–481. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81887-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nan X, Ng HH, Johnson CA, Laherty CD, Turner BM, Eisenman RN. et al. Transcriptional repression by the methyl-CpG-binding protein MeCP2 involves a histone deacetylase complex. Nature. 1998;393:386–389. doi: 10.1038/30764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinowich K, Hattori D, Wu H, Fouse S, He F, Hu Y. et al. DNA methylation-related chromatin remodeling in activity-dependent BDNF gene regulation. Science. 2003;302(5646):890–893. doi: 10.1126/science.1090842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou Z, Hong EJ, Cohen S, Zhao WN, Ho HY, Schmidt L. et al. Brain-specific phosphorylation of MeCP2 regulates activity-dependent Bdnf transcription, dendritic growth, and spine maturation. Neuron. 2006;52(2):255–269. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2006.09.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He DY, Neasta J, Ron D. Epigenetic regulation of BDNF expression via the scaffolding protein RACK1. J Biol Chem. 2010;285(25):19043–19050. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.100693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu H, Sun YE. Reversing DNA methylation: new insight from neuronal activity induced Gadd45b in adult neurogenesis. Sci Signal. 2009;2(64):pe17. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.264pe17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naegele J. Epilepsy and the plastic mind. Epilepsy Curr. 2009;9(6):166–169. doi: 10.1111/j.1535-7511.2009.01331.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tian F, Hu XZ, Wu X, Jiang H, Pan H, Marini AM. et al. Dynamic chromatin remodeling events in hippocampal neurons are associated with NMDA receptor mediated activation of BDNF gene promoter I. J Neurochem. 2009;109(5):1375–1388. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2009.06058.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen CJ, Deng Z, Kim AY, Blobel GA, Lieberman PM. Stimulation of CREB binding protein nucleosomal histone acetyltransferase activity by a class of transcriptional activators. Mol Cell Biol. 2001;21(2):476–487. doi: 10.1128/MCB.21.2.476-487.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harton JA, Zika E, Ting JP. The histone acetyltransferase domains of CREB-binding protein (CBP) and p300/CBP-associated factor are not necessary for cooperativity with the class II transactivator. J Biol Chem. 2001;276(42):38715–38720. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M106652200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Im HI, Hollander JA, Bali P, Kenny PJ. MeCP2 controls BDNF expression and cocaine intake through homeostatic interactions with microRNA-212. Nat Neurosci. 2010;13:1120–1127. doi: 10.1038/nn.2615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuzumaki N, Ikegami D, Tamura R, Hareyama N, Imai S, Narita M. et al. Hippocampal epigenetic modification at brain-derived neurotrophic factor gene induced by an enriched environment. Hippocampus. 2011;21(2):127–132. doi: 10.1002/hipo.20775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Onishchenko N, Karpova N, Sabri F, Castrén E, Ceccatelli S. Long-lasting depression-like behavior and epigenetic changes of BDNF gene expression induced by perinatal exposure to methyl mercury. J Neurochem. 2008;106(3):1378–1387. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2008.05484.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsankova NM, Berton O, Renthal W, Kumar A, Neve RL, Nestler EJ. Sustained hippocampal chromatin regulation in a mouse model of depression and antidepressant action. Nat Neurosci. 2006;9(4):519–525. doi: 10.1038/nn1659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bredy TW, Wu H, Crego C, Zellhoefer J, Sun YE, Barad M. Histone modifications around individual BDNF gene promoters in prefrontal cortex are associated with extinction of conditioned fear. Learn Mem. 2007;14(4):268–276. doi: 10.1101/lm.500907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuchikami M, Morinobu S, Kurata A, Yamamoto S, Yamawaki S. Single immobilization stress differentially alters the expression profile of transcripts of the brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) gene and histone acetylation at its promoters in the rat hippocampus. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2009;12:73–82. doi: 10.1017/S1461145708008997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuchikami M, Yamamoto S, Morinobu S, Takei S, Yamawaki S. Epigenetic regulation of BDNF gene in response to stress. Psychiatry Investig. 2011;7:251–256. doi: 10.4306/pi.2010.7.4.251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mill J, Tang T, Kaminsky Z, Khare T, Yazdanpanah S, Bouchard L. et al. Epigenomic profiling reveals DNA-methylation changes associated with major psychosis. Am J Hum Genet. 2008;82(3):696–711. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2008.01.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keller S, Sarchiapone M, Zarrilli F, Videtic A, Ferraro A, Carli V. et al. Increased BDNF promoter methylation in the Wernicke area of suicide subjects. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2010;67(3):258–267. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2010.9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toledo-Rodriguez M, Lotfipour S, Leonard G, Perron M, Richer L, Veillette S. et al. Maternal smoking during pregnancy is associated with epigenetic modifications of the brain-derived neurotrophic factor-6 exon in adolescent offspring. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet. 2010;153B(7):1350–1354. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.b.31109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devlin AM, Brain U, Austin J, Oberlander TF. Prenatal exposure to maternal depressed mood and the MTHFR C677T variant affect SLC6A4 methylation in infants at birth. PLoS One. 2010;5(8):e12201. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0012201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen ES, Ernst C, Turecki G. The epigenetic effects of antidepressant treatment on human prefrontal cortex BDNF expression. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2011;14(3):427–429. doi: 10.1017/S1461145710001422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rao JS, Keleshian VL, Klein S, Rapoport SI. Epigenetic modification in frontal cortex from Alzheimer disease and bipolar disorder patients. Transl Psychiatry. 2012;2:e132. doi: 10.1038/tp.2012.55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’Addario C, Dell’Osso B, Palazzo MC, Benatti B, Lietti L, Cattaneo E. et al. Selective DNA methylation of BDNF promoter in bipolar disorder: differences among patients with BDI and BDII. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2012;37(7):1647–1655. doi: 10.1038/npp.2012.10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kordi-Tamandani DM, Sahranavard R, Torkamanzehi A. DNA methylation and expression profiles of the brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) and dopamine transporter (DAT1) genes in patients with schizophrenia. Mol Biol Rep. 2012;39(12):10889–10893. doi: 10.1007/s11033-012-1986-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perroud N, Salzmann A, Prada P, Nicastro R, Hoeppli ME, Furrer S. et al. Response to psychotherapy in borderline personality disorder and methylation status of the BDNF gene. Transl Psychiatry. 2013;3:e207. doi: 10.1038/tp.2012.140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim JM, Stewart R, Kang HJ, Kim SY, Kim SW, Shin IS. et al. A longitudinal study of BDNF promoter methylation and genotype with poststroke depression. J Affect Disord. 2013;149(1-3):93–99. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2013.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tadić A, Müller-Engling L, Kang HJ, Kotsiari A, Dreimüller N, Kleimann A. et al. Methylation of the promoter of brain-derived neurotrophic factor exon IV and antidepressant response in major depression. Mol Psychiatry. 2013 doi: 10.1038/mp.2013.58. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- An JJ, Gharami K, Liao GY, Woo NH, Lau AG, Vanevski F. et al. Distinct role of long 3' UTR BDNF mRNA in spine morphology and synaptic plasticity in hippocampal neurons. Cell. 2008;134(1):175–187. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.05.045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lau AG, Irier HA, Gu J, Tian D, Ku L, Liu G. et al. Distinct 3'UTRs differentially regulate activity-dependent translation of brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107(36):15945–15950. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1002929107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pattabiraman PP, Tropea D, Chiaruttini C, Tongiorgi E, Cattaneo A, Domenici L. Neuronal activity regulates the developmental expression and subcellular localization of cortical BDNF mRNA isoforms in vivo. Mol Cell Neurosci. 2005;28(3):556–570. doi: 10.1016/j.mcn.2004.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiaruttini C, Sonego M, Baj G, Simonato M, Tongiorgi E. BDNF mRNA splice variants display activity-dependent targeting to distinct hippocampal laminae. Mol Cell Neurosci. 2008;37(1):11–19. doi: 10.1016/j.mcn.2007.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aliaga EE, Mendoza I, Tapia-Arancibia L. Distinct subcellular localization of BDNF transcripts in cultured hypothalamic neurons and modification by neuronal activation. J Neural Transm. 2009;116(1):23–32. doi: 10.1007/s00702-008-0159-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baj G, Leone E, Chao MV, Tongiorgi E. Spatial segregation of BDNF transcripts enables BDNF to differentially shape distinct dendritic compartments. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108(40):16813–16818. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1014168108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Webster MJ, Herman MM, Kleinman JE, Shannon Weickert C. BDNF and trkB mRNA expression in the hippocampus and temporal cortex during the human lifespan. Gene Expr Patterns. 2006;6(8):941–951. doi: 10.1016/j.modgep.2006.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silhol M, Bonnichon V, Rage F, Tapia-Arancibia L. Age-related changes in brain-derived neurotrophic factor and tyrosine kinase receptor isoforms in the hippocampus and hypothalamus in male rats. Neuroscience. 2005;132(3):613–624. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2005.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cabelli RJ, Shelton DL, Segal RA, Shatz CJ. Blockade of endogenous ligands of trkB inhibits formation of ocular dominance columns. Neuron. 1997;19(1):63–76. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80348-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mandolesi G, Menna E, Harauzov A, von Bartheld CS, Caleo M, Maffei L. A role for retinal brain-derived neurotrophic factor in ocular dominance plasticity. Curr Biol. 2005;15(23):2119–2124. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2005.10.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong J, Webster MJ, Cassano H, Weickert CS. Changes in alternative brain-derived neurotrophic factor transcript expression in the developing human prefrontal cortex. Eur J Neurosci. 2009;29(7):1311–1322. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2009.06669.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calabrese F, Guidotti G, Middelman A, Racagni G, Homberg J, Riva MA. Lack of serotonin transporter alters BDNF expression in the rat brain during early postnatal development. Mol Neurobiol. 2013;48(1):244–256. doi: 10.1007/s12035-013-8449-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olivier JD, Van Der Hart MG, Van Swelm RP, Dederen PJ, Homberg J, Cremers T. et al. A study in male and female 5-HT transporter knockout rats: an animal model for anxiety and depression disorders. Neuroscience. 2008;152(3):573–584. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2007.12.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garzon D, Yu G, Fahnestock M. A new brain-derived neutrophic factor transcript and decrease in brain-derived neurotrophic factor transcripts 1, 2 and 3 in Alzheimer’s disease parietal cortex. J Neurochem. 2002;82(5):1058–1064. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2002.01030.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang X, Zhou J, Mash DC, Marini AM, Lipsky RH. Human BDNF isoforms are differentially expressed in cocaine addicts and are sorted to the regulated secretory pathway independent of the met66 substitution. Neuromolecular Med. 2009;11(1):1–12. doi: 10.1007/s12017-008-8051-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong J, Hyde TM, Cassano HL, Deep-Soboslay A, Kleinman JE, Weickert CS. Promoter specific alterations of brain-derived neurotrophic factor mRNA in schizophrenia. Neuroscience. 2010;169(3):1071–1084. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2010.05.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu B, Pang PT, Woo NH. The yin and yang of neurotrophin action. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2005;6(8):603–614. doi: 10.1038/nrn1726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deinhardt K, Chao MV. Shaping neurons: Long and short range effects of mature and proBDNF signalling upon neuronal structure. Neuropharmacology. 2013 doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2013.04.054. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kenchappa RS, Tep C, Korade Z, Urra S, Bronfman FC, Yoon SO. et al. p75 neurotrophin receptor-mediated apoptosis in sympathetic neurons involves a biphasic activation of JNK and up-regulation of tumor necrosis factor-alpha-converting enzyme/ADAM17. J Biol Chem. 2010;285(26):20358–20368. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.082834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teng KK, Felice S, Kim T, Hempstead BL. Understanding proneurotrophin actions: Recent advances and challenges. Dev Neurobiol. 2010;70(5):350–359. doi: 10.1002/dneu.20768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reichardt LF. Neurotrophin-regulated signalling pathways. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2006;361(1473):1545–1564. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2006.1894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun Y, Lim Y, Li F, Liu S, Lu JJ, Haberberger R. et al. ProBDNF collapses neurite outgrowth of primary neurons by activating RhoA. PLoS One. 2012;7(4):e35883. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0035883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jang SW, Liu X, Yepes M, Shepherd KR, Miller GW, Liu Y. et al. A selective TrkB agonist with potent neurotrophic activities by 7,8-dihydroxyflavone. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107(6):2687–2692. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0913572107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen K, Cowan CW. Guidance molecules in synapse formation and plasticity. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2010;2(4):a001842. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a001842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sossin WS, Barker PA. Something old, something new: BDNF-induced neuron survival requires TRPC channel function. Nat Neurosci. 2007;10(5):537–538. doi: 10.1038/nn0507-537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koshimizu H, Hazama S, Hara T, Ogura A, Kojima M. Distinct signaling pathways of precursor BDNF and mature BDNF in cultured cerebellar granule neurons. Neurosci Lett. 2010;473(3):229–232. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2010.02.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henriques A, Pitzer C, Schneider A. Neurotrophic growth factors for the treatment of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: where do we stand? Front Neurosci. 2010;4:32. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2010.00032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuchikami M, Morinobu S, Segawa M, Okamoto Y, Yamawaki S, Ozaki N. et al. DNA methylation profiles of the brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) gene as a potent diagnostic biomarker in major depression. PLoS One. 2011;6(8):e23881. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0023881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cruz-Fuentes CS, Benjet C, Martínez-Levy GA, Perez-Molina A, Briones-Velasco M, Suárez-González J. BDNF Val 66 Met but not 5HTT-LPR modulates the cumulative effect of psychosocial childhood adversities on Major Depression in adolescents of Mexico City. Brain and Behavior. doi: 10.1002/brb3.220. In Press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]