Abstract

A wealth of comparative data has been accumulated over the past decades on how animals acquire and use information about the physical world. Domestic dogs have typically performed comparably poorly in physical cognition tasks, though in a recent study Kundey and colleagues (2010) challenged this view and concluded that dogs understand that objects cannot pass through solid barriers. However, the eight subjects in the study of Kundey et al. may have solved the task with the help of perceptual cues, which had not been controlled for. Here, we tested dogs with a similar task that excluded these cues. In addition, unlike the setup of Kundey et al., our setup allowed the subjects to observe the effect of the solid barrier. Nevertheless, all 28 subjects failed to solve this task spontaneously, and showed no evidence of learning across 50 trials. Our results therefore call into question the earlier suggestion that dogs have, or can acquire, an understanding of the solidity principle.

Keywords: physical knowledge, object knowledge, perceptual cues, Canis familiaris

Introduction

Over the past decades, a wealth of comparative data has been accumulated on how animals acquire and use information about the physical world (Shettleworth 2010), with examples of striking skills in some cases, but also evidence for reliance on associative rather than causal cues in others. For instance, even New Caledonian crows, a species of gifted tool users, have recently been shown to use perceptual cues to solve connectivity tasks that had previously been used for decades to test for understanding of physical properties or even “insight” (Taylor et al. 2010, 2012). Researchers must therefore be very careful in designing their experiments, controlling for any possible perceptual cues that may help the subjects to solve the task, before arguing in favour of physical or causal understanding in animals. This may be particularly true also for domestic dogs (Canis familiaris), which have typically performed comparably poorly in physical cognition tasks (e.g. Collier-Baker et al. 2004; Osthaus et al. 2005; Bräuer et al. 2006). There is increasing evidence, for instance, that dogs rely on associative cues when trying to locate hidden objects that have been invisibly displaced (Collier-Baker et al. 2004; Fiset and Leblanc 2007; Rooijakkers et al. 2009).

A recent study seemed to call into question the meanwhile dominant view of poor physical cognition skills in dogs: Kundey et al. (2010) presented dogs with a task where they observed a treat roll down a transparent slanted tube into an opaque box, into which a solid barrier could be inserted that interrupted the treat’s trajectory. The subjects subsequently searched for the reward in the correct position from the first trial onwards, at the proximal end when the barrier was present and at the distal end when no barrier was inserted. The authors interpreted this result as evidence that dogs show an understanding of the solidity principle, namely that objects cannot pass through solid barriers, a task at which two-year old human toddlers had failed before (e.g. Berthier et al. 2000; Butler et al. 2002), as had non-human primates (e.g. Santos 2004; Santos et al. 2006; but see also Cacchione et al. 2009).

The results of Kundey and colleagues are not entirely conclusive, however. While the authors controlled for possible effects of olfactory or experimenter cues, they did not equally control for auditory cues, but merely stated that “auditory cues … were similar across trials”. Importantly, their setup will have resulted in sounds of the treat colliding with a solid wall at different locations, with the barrier, when it was inserted, or with the back wall, when the barrier was not inserted. Additionally, the treat may have created small movements of the fabric covering the doors of the apparatus used by Kundey and colleagues1. That is, the dogs may have “solved” the task simply by approaching the position where they saw a movement or where they heard a sound come from.

Here, we tested dogs with a different setup than the one used by Kundey and colleagues, the “blocked tube task”, which tested for dogs’ understanding of the solidity principle in a task where no acoustic or movement cues occurred prior to the subject’s choice. In this task, the dogs had a choice between two transparent horizontal tubes. Initially, the dogs learned to push down the tubes on one end so that the content would fall out. In the critical test trials, both tubes contained a food reward, but one of them was prevented from falling out by an opaque barrier inserted in front of it. In the second tube an identical barrier was inserted behind the reward. In addition to ruling out possibly confounding auditory cues prior to the dog’s choice, our task made the effect of the opaque barrier in the transparent tubes directly observable to the subjects, whereas the effect of the barrier was not observable in the opaque target box of Kundey and colleagues but had to be inferred from indirect cues.

If dogs show a spontaneous understanding of the solidity principle, as suggested by Kundey and colleagues, we would thus predict that dogs solve the blocked tube task from the first trial on, or at least require little learning to develop a significant preference for the non-blocked tube. If the performance of the subjects depends on experiences gathered in their lifetime on how objects interact, an alternative explanation offered by Kundey and colleagues for their results, we would again predict that dogs either solve the blocked tube task from the beginning or show clear evidence of learning across trials.

Methods

Subjects

We tested 29 Border Collies at the age of between 18 and 26 months (11 males, 18 females). All subjects lived as pet dogs with their owners, who volunteered to participate in this study. We tested dogs of a single breed with the aim of reducing variability induced by breed differences and chose Border Collies due to their high availability and motivation to work with humans. Furthermore, we have no reason to assume that Border Collies were selected for performance in physical cognition tasks.

Apparatus and Conditions

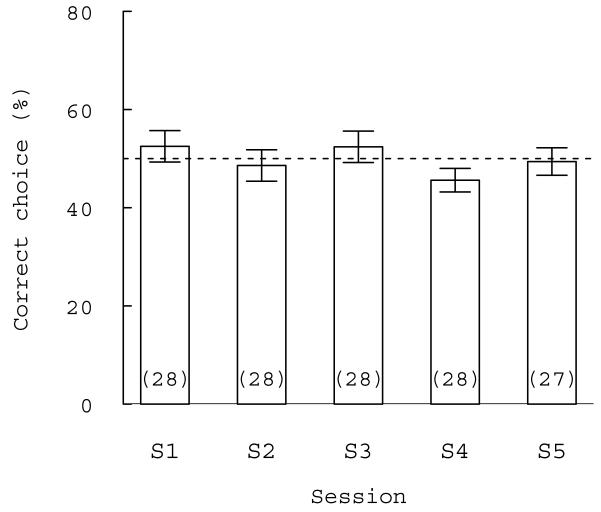

Testing took place in a 5 by 6 m room at the Clever Dog Lab (Nussgasse 4, Vienna). The test apparatus consisted of two 40 cm long quadratic Plexiglas tubes, which were mounted horizontally 40 cm above ground on a wooden wall that was placed against the back wall of the room (Fig. 1a). A cardboard square covered the proximal end of each tube, whereas the distal ends were open. Each tube had two slits where barriers (3mm thick dark grey plastic boards) could be inserted (cf. Fig. 1a). The tubes were held in position by a pivot at the proximal end and a magnet at the distal end. The magnet could be released by applying ca. 1 kg of pressure to the handle attached at a 45° angle to the distal end of the tube (Fig. 1a), causing the tube to tilt downwards and the reward placed in the tube to roll out. Springs attached to the tubes prevented them from tilting too fast (and scaring the subject). A board (60 wide and 150 cm high) was placed perpendicular to the back wall on either side of the apparatus to force the subject to approach the apparatus from the front rather than from the side (Fig. 1b).

Fig. 1. Photographic depiction of two symmetrical halves of the experimental apparatus from dog’s point of view (a) and schematic layout of the testing room with the apparatus marked in grey (b).

a shows the state of the apparatus after an incorrect choice of the blocked condition. Circles in b give start positions for experimenter 1 and 2 respectively. For each trial, experimenter 1 approached the apparatus from the left or the right, placed the occluder between himself and the dog and, after baiting the apparatus, returned the occluder to its position before returning to his start position behind the partition.

After some initial shaping (see Procedures below), the dogs were tested with two different conditions: in the first condition (free condition), a 2 cm section of sausage was placed in one of the tubes, whereas the other tube was left empty. This condition served (1) to confirm that the dogs could reliably operate the apparatus without help, (2) to offer them the opportunity to observe the physical contingency of the apparatus, namely that the sausage would roll out of the tube when it was tilted, and (3) to ensure that the dogs could perceive the reward in the tube. Subjects were tested in the second condition only if they chose the baited tube at least eight times in a session of ten trials of the free condition. In the second condition (blocked condition), a reward was placed in both tubes in the same relative position (25 cm from the opening), and in both tubes a barrier was inserted, either 4 cm in front of or 4 cm behind the reward (cf. Fig. 1a). That is, in this condition the dogs had to choose the tube in which the reward was not blocked from rolling out (since it could not pass through the barrier when the tube was tilted). A supplementary experiment conducted after the blocked condition furthermore confirmed that dogs could perceive the opaque barrier when inserted into the transparent tubes (see supplementary information S1).

Procedures

Before testing, each dog was trained to operate the apparatus with a shaping procedure. In this phase, no rewards were placed in the apparatus but the experimenter rewarded the dog with treats from a pouch, initially for approaching the handle of one of the tubes with the mouth or the paw, then for touching it and finally for pushing or pulling it down. Care was taken that shaping was split equally between the two sides of the apparatus. In case of lacking motivation by the dog, several small pieces of dry food were placed into the tubes. This shaping was continued, if necessary with breaks in between, until the dog reliably and quickly released the tubes by the handles. The shaping period lasted between 5 and 45 minutes per subject (median 14 min), mostly depending on the boldness of their approach to the apparatus.

The subjects received a maximum of three sessions of the free condition, if successful followed by five sessions of the blocked condition. Each session consisted of ten trials. Two to four (median 3) sessions were conducted per day, with a break of at least five minutes between sessions, during which dog and experimenters left the testing room. Test days were separated by a median of 7 days (range 2-46, depending on availability of the owners). On the seven occasions where testing was continued after a break of more than two weeks, two trials of the free condition (one per side) were conducted initially to ensure that the dogs still remembered how to operate the apparatus. On all of these occasions, the dogs immediately and successfully obtained the rewards in all trials. Within sessions, the correct side was varied pseudorandomly so that the same side was correct never more than twice in a row and both sides were rewarded equally often.

For each test trial, experimenter 2 (E2) led the dog to the starting position, 1 m in front of the apparatus (cf. Fig. 1b), and put on a blindfold. Thereafter, experimenter 1 (E1) placed an occluder between dog and apparatus, baited the apparatus, removed the occluder and walked back to his start position behind the dog (see also supplementary videos). For this, E1 approached the apparatus randomly from the left or the right side. Five seconds after E1 had removed the occluder, E2 released the dog, additionally giving a verbal “go” command for dogs that did not leave on their own accord. In cases where the dog was not oriented toward the apparatus when the occluder was removed, E2 delayed release accordingly. E2 removed the blindfold once the dog had left the start position and retrieved the dog once it had pushed down one of the two tubes. The dog was prevented from pushing down the second tube after a wrong choice, except in the last trial of each session. This exception served to maintain motivation of the dog (which thus always left the test room with a success), showed the dog that there is a correct choice also when its first choice did not lead to a reward, and aimed to help reduce the probability that dogs would fall into complete side biases and operate only one side of the apparatus while ignoring the other. No-choice trials (the dog did not directly approach either of the two tubes after being released, but instead went exploring the room or walked to the door, n = 6 trials) were repeated, as were trials with experimenter error (i.e. both tubes rewarded or both tubes non-rewarded, n = 7 trials).

Analyses

A correct choice was coded if the dog released the correct tube first and thus obtained the reward. Coding was done from video recordings, with the exception of 30 trials (of the total 1830) where due to equipment failure we used data from notes taken by E1 during the experiment. Concordance between notes and video coding was high (100% based on 20 randomly selected sessions (200 trials)).

All analyses were performed in R 2.15.1 (R Core Team 2012). The choice data were analysed with binomial generalized linear models (GLMs) with logit link, with number of correct choices in the numerator and number of trials in the denominator of the response variable. GLMs were run with correction for over-dispersion if applicable. We used generalized linear mixed models (GLMMs) with dog identity included as a random effect to test for learning across sessions (using R package lme4, Bates et al. 2012). To determine whether correct choice probability differed from the chance level for particular sessions, we tested whether the intercept differed from 0 (=log(1), corresponding to the chance level of 50%) in GLMs with the intercept as the only predictor.

Ethical Note

The experiments and procedures presented in this manuscript adhered to the ‘Guidelines for the treatment of animals in behavioural research and teaching’ as published by the ASAB (2006) and comply with the current laws of the country in which they were performed.

Results

Free Condition

Group performance was significantly above chance in the first session with 73.2% correct choices (GLM: t(28)=5.47, p<0.001). Fourteen of the 29 dogs passed the individual criterion in their first session, a further 12 dogs passed the criterion in the second, and 2 dogs in the third session. One dog did not reach criterion in the third session (6 of 10 correct choices) and did not proceed to the blocked condition.

Blocked Condition

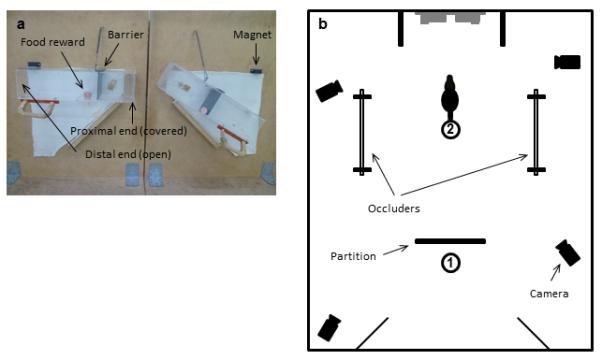

Group performance was not significantly different from chance level in the first session with 52.5% correct choices (GLM: z=0.84, p=0.40). Furthermore, group performance did not change significantly across sessions (GLMM: z=-0.97, p=0.33; Fig. 2). In addition, a Bayesian analysis (after Gallistel 2009) provided substantial support for the null hypothesis that group performance did not differ from chance level (see supplementary material S2 for details). On the individual level, none of the subjects performed significantly above chance level in the first two or in the last two sessions (criterion: at least 80% correct choices for two consecutive sessions, binomial probability < 0.02).

Fig. 2. Percent correct choices for the five sessions of the blocked condition.

Numbers in parentheses give sample sizes (one subject completed only four sessions). The dashed line indicates chance level. Data are displayed as mean and standard error.

Discussion

None of the tested subjects solved the blocked tube task, which required them to understand, or learn, that the treat could not pass through a solid barrier. Also at group level, despite a sample that was three times the size of the one presented by Kundey and colleagues (2010), no evidence was found that dogs could solve the blocked tube task. These results stand in stark contrast to the conclusion of Kundey and colleagues that dogs spontaneously show an understanding of the solidity principle. We suggest that the dogs in the earlier study may have solved the task by following cues that indicated the location of the reward (cues that were not available in our setup). This interpretation is also supported by the findings of Bräuer and colleagues (2006), who showed that dogs are attracted by acoustic cues in a two choice task, irrespective of whether these cues signal presence of the reward (causal cue) or not (arbitrary cue). Furthermore, Heffner and Heffner (1992) showed that dogs can reliably localize sounds separated by as little as 8 arc degrees, which is well below the separation of the barrier and the back wall in the study by Kundey and colleagues. However, we acknowledge that our task differed from the task used by Kundey and colleagues in several ways. Perhaps most importantly, to solve the task, the dogs in our study were required to infer what would happen as a consequence of their action, whereas the subjects in the study of Kundey and colleagues had to infer what had happened in the opaque box prior to making a choice. Furthermore, unlike us, Kundey and colleagues used ostensive cueing to attract their subjects’ attention to the (functionally relevant) barrier. Therefore, the exact reasons for the discrepancy between their and our results remain unclear.

The dogs in our study not only failed to show a preference for the not-blocked tube in the initial trials, they also showed no evidence of learning across the five test sessions, even though only few individuals fell into a side bias (cf. supplementary material S3). This finding contradicts the interpretation that dogs may acquire an understanding of the solidity principle through experiences gathered by observation of events in their environment (Kundey et al. 2010). Given that the causal mechanism in our study was observable to the dogs, our finding rather suggests that dogs do not necessarily pay attention to causally relevant information available, unlike great apes for example, which appear to focus on causally relevant cues when learning a choice task (Hanus and Call 2011).

To conclude, our data call into question the earlier conclusion that dogs show an understanding of the solidity principle. Furthermore, our results underline the well-known but rarely heeded need for replication of behavioural studies, also using different paradigms, before they get accepted as proof, in particular if they suggest sophisticated cognitive skills and/or stand in contrast with the existing literature at large.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank Alina Gaugg, Amelie Göschl, Elisabeth Pikhart, Magdalena Weiler and Elena Zanchi for help with the experiments, the dog owners for participation and the reviewers for constructive comments. This work was funded by the Austrian Science Fund (FWF grant P21418 to L.H. and F.R.). S.R. was also supported by the DK CogCom Programme (FWF Doctoral Programs W1234), and the Clever Dog Lab received financial support from Royal Canin and a private sponsor.

Footnotes

We thank one of the anonymous reviewers for pointing out this possibility.

References

- ASAB Guidelines for the treatment of animals in behavioural research and teaching. Anim Behav. 2006;71:245–253. doi: 10.1006/anbe.1999.1349. doi: 10.1016/j.anbehav.2005.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bates D, Maechler M, Bolker B. lme4: Linear mixed-effects models using S4 classes. R package version 0.999999-0. 2012 http://cran.r-project.org/package=lme4.

- Berthier NE, DeBlois S, Poirier CR, et al. Where’s the ball? Two- and three-year-olds reason about unseen events. Dev Psychol. 2000;36:394–401. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.36.3.394. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.36.3.394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bräuer J, Kaminski J, Riedel J, et al. Making inferences about the location of hidden food: social dog, causal ape. J Comp Psychol. 2006;120:38–47. doi: 10.1037/0735-7036.120.1.38. doi: 10.1037/0735-7036.120.1.38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butler SC, Berthier NE, Clifton RK. Two-year-olds’ search strategies and visual tracking in a hidden displacement task. Dev Psychol. 2002;38:581–590. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.38.4.581. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.38.4.581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cacchione T, Call J, Zingg R. Gravity and solidity in four great ape species (Gorilla gorilla, Pongo pygmaeus, Pan troglodytes, Pan paniscus): vertical and horizontal variations of the table task. J Comp Psychol. 2009;123:168–180. doi: 10.1037/a0013580. doi: 10.1037/a0013580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collier-Baker E, Davis JM, Suddendorf T. Do dogs (Canis familiaris) understand invisible displacement? J Comp Psychol. 2004;118:421–433. doi: 10.1037/0735-7036.118.4.421. doi: 10.1037/0735-7036.118.4.421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiset S, Leblanc V. Invisible displacement understanding in domestic dogs (Canis familiaris): the role of visual cues in search behavior. Anim Cogn. 2007;10:211–224. doi: 10.1007/s10071-006-0060-5. doi: 10.1007/s10071-006-0060-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallistel CR. The importance of proving the null. Psychological Review. 2009;116:439–453. doi: 10.1037/a0015251. doi: 10.1037/a0015251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanus D, Call J. Chimpanzee problem-solving: contrasting the use of causal and arbitrary cues. Anim Cogn. 2011;14:871–878. doi: 10.1007/s10071-011-0421-6. doi: 10.1007/s10071-011-0421-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heffner R, Heffner H. Hearing in large mammals: sound-localization acuity in cattle (Bos taurus) and goats (Capra hircus) J Comp Psychol. 1992;106:107–113. doi: 10.1037/0735-7036.106.2.107. doi: 10.1037//0735-7036.106.2.107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kundey SMA, De Los Reyes A, Taglang C, et al. Domesticated dogs’ (Canis familiaris) use of the solidity principle. Anim Cogn. 2010;13:497–505. doi: 10.1007/s10071-009-0300-6. doi: 10.1007/s10071-009-0300-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osthaus B, Lea SEG, Slater AM. Dogs (Canis lupus familiaris) fail to show understanding of means-end connections in a string-pulling task. Anim Cogn. 2005;8:37–47. doi: 10.1007/s10071-004-0230-2. doi: 10.1007/s10071-004-0230-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- R Core Team . R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing; Vienna, Austria: 2012. http://www.R-project.org/ ISBN: 3-900051-07-0. [Google Scholar]

- Rooijakkers EF, Kaminski J, Call J. Comparing dogs and great apes in their ability to visually track object transpositions. Anim Cogn. 2009;12:789–796. doi: 10.1007/s10071-009-0238-8. doi: 10.1007/s10071-009-0238-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santos LR. “Core knowledges”: a dissociation between spatiotemporal knowledge and contact-mechanics in a non-human primate? Dev Sci. 2004;7:167–174. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-7687.2004.00335.x. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-7687.2004.00335.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santos LR, Seelig D, Hauser MD. Cotton-top tamarins’ (Saguinus oedipus) expectations about occluded objects: a dissociation between looking and reaching tasks. Infancy. 2006;9:147–171. doi: 10.1207/s15327078in0902_4. [Google Scholar]

- Shettleworth SJ. Cognition, Evolution and Behavior. 2nd ed Oxford University Press; Oxford: 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor AH, Knaebe B, Gray RD. An end to insight? New Caledonian crows can spontaneously solve problems without planning their actions. Proc R Soc B. 2012;279:4977–4981. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2012.1998. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2012.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor AH, Medina FS, Holzhaider JC, et al. An investigation into the cognition behind spontaneous string pulling in New Caledonian crows. PLoS One. 2010;5:e9345. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0009345. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0009345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.