Abstract

Background

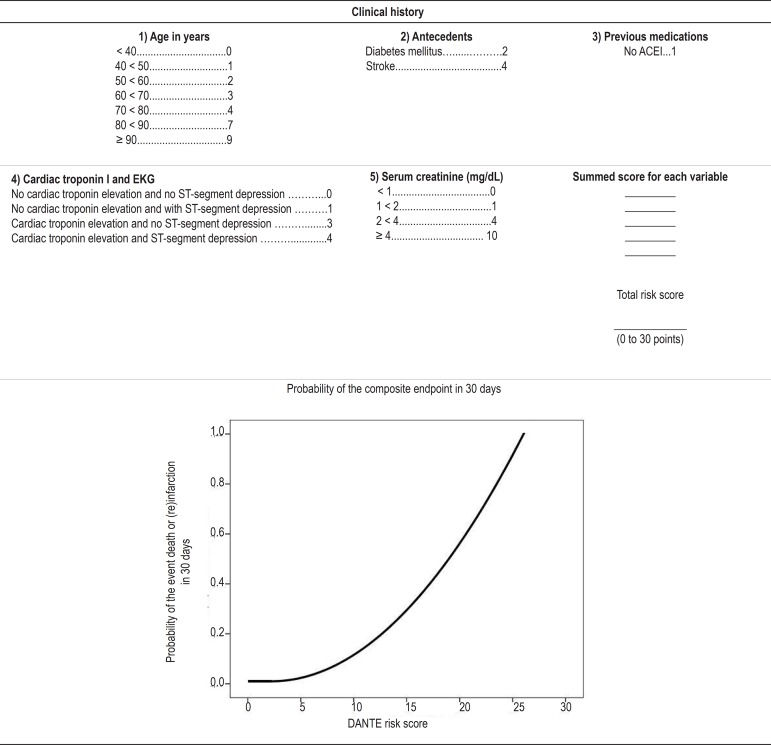

In non-ST-segment elevation acute coronary syndrome (ACS), the likelihood of adverse events should be estimated. Guidelines recommend risk stratification models for that purpose. The Dante Pazzanese risk score (DANTE score) is a simple risk stratification model composed with the following variables: age increase (0 to 9 points); history of diabetes mellitus (2 points) or stroke (4 points); no use of angiotensin-converting-enzyme inhibitor (1 point); creatinine elevation (0 to 10 points); combination of troponin elevation and ST-segment depression (0 to 4 points).

Objective

To validate the DANTE score in patients with non-ST-segment elevation ACS.

Methods

Prospective, observational study including 457 patients, from September 2009 to October 2010. The patients were grouped in risk categories according to the original model score as follows: very low; low; intermediate; and high. The predictive ability of the score was assessed by using C-statistics.

Results

The sample comprised 291 (63.7%) men, the mean age being 62.1 years (SD=11.04). The event death or (re) infarction in 30 days was observed in 17 patients (3.7%). Progressive increase in the proportion of events was observed as the score increased: very low risk = 0.0%; low risk = 3.9%; intermediate risk = 10.9%; high risk = 60.0%; p < 0.0001. C-statistics was 0.87 (95% CI: 0.81-0.94; p < 0.0001).

Conclusion

DANTE score showed an excellent capacity to predict the specific events, and can be incorporated to the prognostic assessment of patients with non-ST-segment elevation ACS.

Keywords: Acute Coronary Syndrome / diagnosis, Validation Studies, Propensity Score, Risk, Probability

Introduction

Cardiovascular diseases are an important cause of death worldwide. They usually represent the main cause of death not only in developed but also in developing countries1. Because of the heterogeneous nature of patients with non-ST-segment elevation acute coronary syndrome (ACS), such as unstable angina or acute myocardial infarction (AMI), the risk of death or recurrent ischemic events varies2-7. Determining the risk of those adverse events is important to define the ideal place for medical care provision, and to identify patients who might benefit from a more effective, expensive and often risky management2.

Currently, the risk stratification for that population involves independent prognostic variables and risk stratification models recommended by national and international guidelines8-10.

The Dante Pazzanese score for risk stratification11 (DANTE score) has shown a good ability (C-statistics, 0.74) to assess the likelihood of the composite endpoint of death or (re)infarction in up to 30 days in the population it was developed, incorporating the following variables easily collected in daily medical practice: age; history of diabetes mellitus or stroke; no use of angiotensin-converting-enzyme inhibitor prior to hospitalization; ST-segment depression ≥ 0.5 mm on electrocardiogram at admission; cardiac troponin level elevation; and creatinine level elevation (Figure 1). It is a simple risk stratification model developed in a Brazilian population with non-ST-segment elevation ACS, which is easily performed and has a high predictive value for cardiovascular events.

Figure 1.

DANTE11 risk score for non-ST-segment elevation acute coronary syndrome. ACEI: angiotensin-converting-enzyme inhibitor; EKG: electrocardiogram.

Methods

Study population

This study aimed to perform the external validation of the DANTE risk score in patients with non-ST-segment elevation ACS.

This was a prospective study with consecutive inclusion of patients with non-ST-segment elevation ACS, admitted to the emergency unit of a cardiology tertiary center from September 8th, 2009, to October 8th, 2010. Patients aged at least 18 years and with symptoms consistent with acute coronary ischemia within the last 48 hours were eligible for this study. Patients with the following characteristics were excluded: ST-segment elevation AMI; noncardiac symptoms; secondary unstable angina; and confounding electrocardiographic (EKG) changes, such as pacemaker rhythm, atrial fibrillation rhythm, and bundle-branch blocks. The local Committee on Ethics and Research approved the study protocol.

Clinical outcomes

During hospitalization, the patients were followed up with medical visits at the emergency unit, the coronary unit or at the ward, and later, after hospital discharge, through telephone contact, to assess the incidence of death or (re)infarction in up to 30 days.

Within the first 24 hours after admission, patients were considered to experience the outcome of (re)infarction if they had ischemic symptoms with persistent ST-segment elevation greater than 0.1 mV on at least two contiguous leads, which were not present on admission. During that period, the elevation of CK-MB or cardiac troponin I levels with no ST-segment elevation was considered to be related to the event of admission. After 24 hours, (re)infarction was diagnosed by the presence of new Q waves or new CK-MB level elevation above the normal limit with or without EKG changes. Patients undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) or coronary artery bypass graft surgery required a CK-MB level elevation greater than three or five times the normal limit, respectively, after the procedure12 to be diagnosed with procedure-related infarction.

DANTE score calculation

Basal, laboratory and EKG characteristics were recorded on hospital admission and during hospitalization. DANTE score was calculated for each patient according to the specific prognostic variables of the original model, being the risk categories as follows: very low (up to 5 points); low (6 to 10 points); intermediate (11 to 15 points); and high (16 to 30 points).

Statistical analysis

The quantitative variables were presented as means, percentiles (25th percentile and 75th percentile), medians and standard deviations (SD). Qualitative variables were expressed as absolute frequencies or percentages. Pearson chi-square test or Fisher exact test was used to compare qualitative variables, and the non-parametric Mann-Whitney test to compare quantitative variables between the original model11 and validation populations.

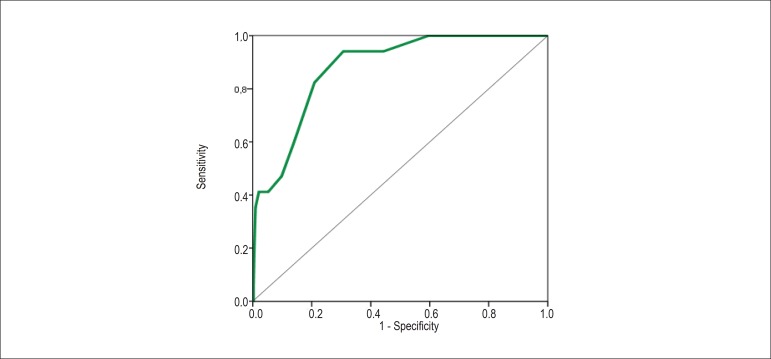

The DANTE score discriminatory capacity was analyzed by determining the area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (ROC)13, represented by C-statistics14.

Results

Baseline characteristics

This study population consisted of 457 patients with non-ST-segment elevation ACS, of whom, 169 (37%) had non-ST-segment elevation AMI and 288 (63%) had unstable angina. Their mean age was 62.1 years (SD = 11.04), and 291 (63.7%) were of the male sex. The most frequent risk factor was systemic arterial hypertension (85.3%), followed by dyslipidemia (75.9%). Almost half of the patients (49.5%) had already undergone a myocardial revascularization procedure. Table 1 shows the baseline characteristics of the population studied.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the population of the DANTE score original model development11 and of its validation

| Characteristics | Population of the original model development11(n = 1027) | Validation population (n = 457) | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age in years (mean [SD]/median [25th percentile; 75th percentile]) | 61.5 (11.05) / 67.0 (53.0; 70.0) | 62.1 (11.04) / 61.0 (54.0; 70.0) | 0.455 |

| Male sex, n (%) | 589 (57.4) | 291 (63.7) | 0.002 |

| Smoking habit, n (%) | 213 (20.7) | 110 (24.1) | 0.151 |

| Diabetes mellitus, n (%) | 329 (32.0) | 160 (35.0) | 0.260 |

| Systemic arterial hypertension, n (%) | 787 (76.6) | 390 (85.3) | < 0.0001 |

| Dyslipidemia, n (%) | 659 (64.2) | 347 (75.9) | < 0.0001 |

| Family history of early CAD, n (%) | 295 (38.5) | 172 (37.6) | 0.763 |

| Previous ACS, n (%) | 610 (59.4) | 275 (60.2) | 0.778 |

| Peripheral arterial disease, n (%) | 52 (5.1) | 11 (2.4) | 0.010 |

| Previous stroke, n (%) | 56 (5.5) | 30(6.6) | 0.397 |

| Previous CAD ≥ 50%, n (%) | 584 (56.9) | 287 (62.8) | 0.030 |

| Previous MR procedures (PCI and/or surgery), n (%) | 440 (42.8) | 226 (49.5) | 0.018 |

| Previous medications | |||

| Beta-blocker, n (%) | 591 (57.5) | 289 (63.4) | 0.035 |

| Aspirin, n (%) | 729 (71.0) | 337 (73.9) | 0.248 |

| Statin, n (%) | 466 (45.4) | 278 (61.0) | < 0.001 |

| ACEI, n (%) | 577 (56.2) | 242 (53.0) | 0.248 |

| ST-segment depression > 0.5 mm in at least one lead, except for aVR, n (%) | 268 (26.1) | 99 (21.7) | 0.068 |

| Creatinine in mg/dl (mean [SD]/median [25lh percentile; 75th percentile])* | 1.13 (0.5) / 1.0 (0.9; 1.2) | 1.17 (0.49) / 1.1 (0.9; 1.3) | 0.020 |

| cTnI elevation, n (%) | 304 (29.6) | 169 (37.0) | 0.005 |

| Diagnostic | |||

| non-STSE infarction, n (%) | 258 (25.1) | 169 (37.0) | < 0.0001 |

| unstable angina, n (%) | 769 (74.9) | 288 (63.0) | |

| Medications during hospitalization | |||

| Beta-blocker, n (%) | 955 (93.0) | 433 (94.7) | 0.203 |

| Aspirin, n (%) | 1001 (97.5) | 451 (98.7) | 0.136 |

| Intravenous nitrate, n (%) | 968 (94.3) | 317 (69.4) | < 0.0001 |

| Thrombin inhibitors, n (%) | 986 (96.0) | 440 (96.3) | 0.803 |

| Clopidogrel, n (%) | 896 (87.2) | 440 (96.3) | < 0.0001 |

| Statin, n (%) | 969 (94.4) | 438 (95.8) | 0.232 |

| ACEI, n (%) | 864 (84.1) | 358 (78.3) | 0.007 |

| Coronary angiography, n (%) | 734 (71.5) | 319 (70.0) | 0.553 |

| MR procedure | |||

| PCI, n (%) | 276 (25.9) | 107 (23.4) | 0.08 |

| MR surgery, n (%) | 141 (13.7) | 51 (11.2) | |

| Outcome | |||

| In-hospital death, n (%) | 21 (2.0) | 11 (2.4) | 0.657 |

| In-hospital (re)infarction, n (%) | 12 (1.2) | 5(1.1) | 0.901 |

| DANTE score outcome (death or [re]infarction in 30 days), n (%) | 54 (5.0) | 17 (4.0) | 0.200 |

n: number of patients; SD: standard deviation; CAD: coronary artery disease; ACS: acute coronary syndrome; PCI: percutaneous coronary intervention; MR: myocardial revascularization; ACEI: angiotensin-converting-enzyme inhibitor; cTnl: cardiac troponin I; STSE: ST-segment elevation.

Treatment and outcome

Similarly to the population of the original model development11, patients in the validation population were treated with beta-blockers (94.7%), acetylsalicylic acid (98.7%), thrombin inhibitors (96.3%), thienopyridine derivatives (96.3%), angiotensin-converting-enzyme inhibitors (78.3%), and statin (95.8%).

Percutaneous coronary intervention was indicated to 107 patients (23.4%), and coronary artery bypass graft surgery, to 51 (11.2%).

During hospitalization, 11 patients died (2.4%) and 5 (1.1%) had (re)infarction.

The composite endpoint of death or (re)infarction in 30 days was observed in 17 patients (3.7%), corresponding to the DANTE score event. The (re)infarctions observed were related to the following: PCI in two; coronary artery bypass graft surgery in two; and clinical treatment in one.

Table 1 shows the differences between the original model and validation populations.

DANTE risk score calculation

The DANTE risk score was calculated for each patient according to the specific score of each variable of the original model (Figure 1). The distribution of the risk categories was as follows: very low (178 patients, 38.9%); low (228 patients, 49.9%); intermediate (46 patients, 10.0%); and high (5 patients, 1.1%).

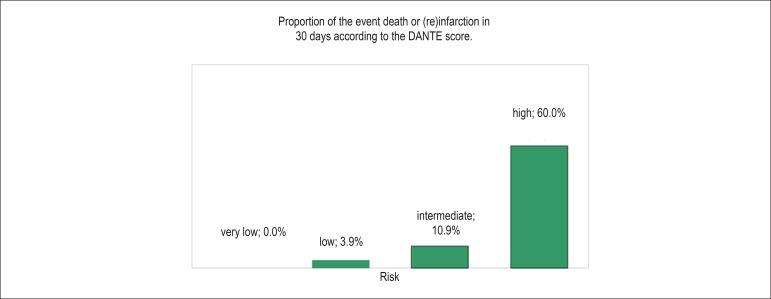

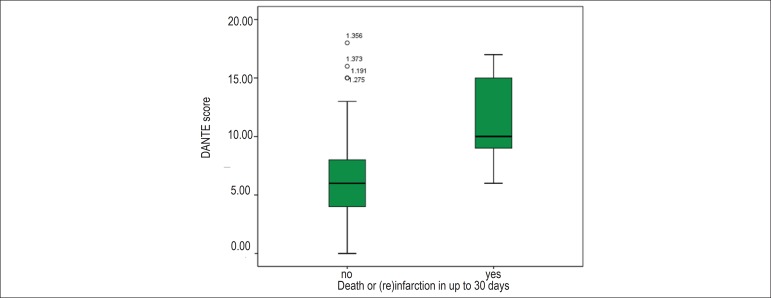

A progressive increase in the proportion of the DANTE score specific event was observed with the gradual increase in scoring as follows: very low risk, 0.0%; low, 3.9% (9 patients); intermediate, 10.9% (5 patients); high risk, 60.0% (3 patients) (Chart 1). Similarly, the mean final DANTE score was significantly higher in patients having the event, as follows: for patients without the event, the mean DANTE score was 6.2 (SD=2.9), and the median, 6.0 (25th percentile = 4.0; 75th percentile = 8.0); for patients with the event, the mean DANTE score was 11.5 (SD=3.4), and the median, 10.0 (25th percentile = 9.0; 75th percentile = 15.0); p < 0.0001 (Chart 2).

Chart 1.

DANTE score event: death or (re)infarction in 30 days; risk categories of the DANTE score: very low = 0 to 5 points; low = 6 to 10 points; intermediate = 11 to 15 points; high = 16 to 30 points.

Chart 2.

Mean and median of the DANTE score of patients with and without the event death or (re)infarction in up to 30 days. Patients without the event of the DANTE score: mean: 6.2 (SD=2.9), median: 6.0 (25th percentile = 4.0; 75th percentile = 8.0); patients with the event of the DANTE score: mean: 11.5 (SD=3.4), median: 10.0 (25th percentile = 9.0; 75th percentile = 15.0); p < 0.0001.

C-statistics (area under the ROC curve) evidenced the excellent predictive ability of the DANTE score to discriminate those with or without the compound event of death or (re)infarction in 30 days: C-statistics, 0.87; 95% confidence interval: 0.81-0.94, p < 0.0001 (Chart 3).

Chart 3.

Area under the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve for the occurrence of the event death or (re)infarction in 30 days, using the DANTE score. C-statistics, 0.87; 95% confidence interval: 0.81-0.94, p < 0.0001.

Discussion

Up to the 1990s, assessing the risk of adverse events in ACS meant almost exclusively assessing the presence of left ventricular dysfunction or residual ischemia in patients with an episode of AMI15. In 1994, Braunwald et al4, for the first time, considered risk stratification for patients with non-ST-segment elevation ACS4,16. In 2000, in the North American guidelines, that strategy began to be considered a level I recommendation17, being maintained in the 2007 guidelines10. Currently, risk stratification is part of medical management already on the first physician-patient contact at the emergency unit.

Risk stratification is important to the initial screening at the emergency unit, this being considered the major role of emergency services, for both the safer discharge of patients and prompter admission of those at high risk for medical management. Its objective is to determine the prognosis of each patient, planning the course of treatment and providing information to patients and their families18. It should be initiated on admission and updated during hospitalization, so that certain medical managements could be adopted in the short run. On admission, the adoption of more intensive measures, such as an aggressive medical treatment or an early invasive strategy, should be based on risk stratification for the occurrence of adverse events. Thus, the focus is to assess the likelihood of adverse events, especially death or (re)infarction, in an increasingly simple and objective manner, analyzing the clinical history, physical exam, EKG, and myocardial necrosis markers.

In the report of the American College of Cardiology and American Heart Association Task Force on practice guidelines, the models of risk stratification are considered as level IIa recommendation10. Different risk stratification models have been developed by using randomized clinical trial populations2,19 that were not primarily selected for the elaboration of a risk score. Thus, the generalization of those models in real world could be questioned. In addition, in clinical trials, the exclusion of patients without ischemic changes on EKG or without an elevation in myocardial necrosis markers is usual. This could originate a true selection bias, because the inclusion of certain EKG changes, as well as of myocardial necrosis markers, would be "pressed" to remain in the final model.

When choosing the clinical outcomes analyzed, heterogeneity is considered another important fact; while in some models, all-cause mortality was assessed20,21, others included death or (re)infarction19, or associated outcomes whose definition in literature showed no consistency and that are influenced by local medical practices, such as urgent myocardial revascularization due to recurring ischemia2.

In Brazil, the risk stratification of patients with non-ST-segment elevation ACS is based on risk scores developed in populations demographically different from the Brazilian one. Because of the large number of patients with that heterogeneous syndrome in Brazil, the development of a model in a typically Brazilian population is recommended.

With data obtained from clinical history, physical exam, EKG and myocardial necrosis markers, routinely collected at the emergency unit, the DANTE score11 provides risk stratification by applying a model developed in a population demographically similar to the Brazilian one.

In the population in which the original model of the DANTE score was developed, it showed to be a good predictor of the adverse events of death or (re)infarction in 30 days, represented by a C-statistics of 0.7411. However, when assessing model performance, its analysis in an independent population was not included. Thus, our study provides the first external validation of the DANTE score.

The patients of the validation population, similarly to those of the population of the original model development, were intensely medicated with beta-blockers, acetylsalicylic acid, thrombin inhibitors, angiotensin-converting-enzyme inhibitors, and statin. However, the use of clopidogrel was significantly higher in the validation population (p < 0.0001), while that of nitroglycerin was significantly lower (p < 0.0001).

Performing coronary angiography did not significantly differ as compared with the population of the original model development (70.0% versus 71.5%; p = 0.553), although the study population had a higher risk, evidenced by a larger number of patients with risk factors for coronary artery disease (systemic arterial hypertension or dyslipidemia) and greater occurrence of coronary artery disease ≥ 50% or myocardial revascularization procedures prior to hospitalization. Similarly, a larger number of patients showed an elevation in myocardial necrosis markers (37.0% in the validation population versus 29.6% in the population of the original model development; p = 0.005).

In-hospital mortality was considerably low (2.4%), confirming previous reports22, and did not differ from that of the population of the original model development (p = 0.657). The combined outcome of death or (re)infarction in 30 days (outcome of the DANTE score) was 4.0% for the validation population versus 5.3% for the population of the original model development11, no significant difference (p = 0.2).

With a summed score for the variables of the DANTE score for each patient, an increase in the risk of adverse events was observed with the gradual increase in the final score, representing, thus, the external validation of the DANTE score. By use of a nomogram, the likelihood of the occurrence of death or (re)infarction in 30 days is obtained.

The DANTE score showed an excellent performance to assess the prognosis of that independent population, reflected in the C-statistics of 0.87, justifying once more its applicability, even in a population at higher risk.

A model including a Brazilian population in its elaboration is believed to play a better role in the prognostic assessment of that population. However, as any model of risk stratification, it should be reassessed in the long run to analyze the existing variables and to incorporate new ones.

Limitations

In this study of external validation, the joint analysis of risk stratification models recommended by current guidelines, such as Braunwald's risk stratification16, TIMI2 and GRACE20,21 risk scores, was not performed. It is worth noting that future studies should perform the joint validation of those models and the DANTE score, especially assessing the database of multicenter Brazilian registries23.

Conclusions

The DANTE risk score showed to be an excellent predictor of the occurrence of death or (re)infarction in 30 days, regardless of the population of the original model development, and can be incorporated in the prognostic assessment of patients with non-ST-segment elevation ACS.

Footnotes

Author Contributions:

Conception and design of the research: Santos ES; Analysis and interpretation of the data: Santos ES, Minuzzo L, Souza R, Timerman A; Acquisition of data: Santos ES, Minuzzo L; Statistical analysis: Santos ES, Souza R; Writing of the manuscript: Santos ES; Critical revision of the manuscript for intellectual content: Santos ES, Minuzzo L, Timerman A.

Potential Conflict of Interest

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

Sources of Funding

There were no external funding sources for this study.

Study Association

This study is not associated with any post-graduation program.

References

- 1.Laurenti R, Buchalla CM, Caratin Vde S. Doença isquêmica do coração: internações, tempo de permanência e gastos. Arq Bras Cardiol. 2000;74(6):483–487. doi: 10.1590/s0066-782x2000000600001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Antman EM, Cohen M, Bernink PJ, McCabe CH, Horacek T, Papuchis G, et al. The TIMI risk score for unstable angina/non-ST elevation MI: A method for prognostication and therapeutic decision making . JAMA. 2000;284(7):835–842. doi: 10.1001/jama.284.7.835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Farhi JI, Cohen M, Fuster V. The broad spectrum of unstable angina pectoris and its implications for future controlled trials. Am J Cardiol. 1986;58(6):547–550. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(86)90031-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Braunwald E, Mark DB, Jones RH, Brown J, Brown L, Cheitlin MD, Concannon CA, Cowan M, Edwards C, Fuster V. nstable Angina: Diagnosis and Management. Clinical Practice Guideline Number 10. Rockville. Md : Agency for Health Care Policy and Research and the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, Public Health Service, US Department of Health and Human Services; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Calvin JE, Klein LW, VandenBerg BJ, Meyer P, Condon JV, Snell RJ, et al. Risk stratification in unstable angina: prospective validation of the Braunwald classification. JAMA. 1995;273(2):136–141. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Armstrong PW, Fu Y, Chang WC, Topol EJ, Granger CB, Betriu A, et al. Acute coronary syndromes in the GUSTO-IIb trial: prognostic insights and impact of recurrent ischemia. The GUSTO-IIb Investigators. Circulation. 1998;98(18):1860–1868. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.98.18.1860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zaacks SM, Liebson PR, Calvin JE, Parrillo JE, Klein LW. Unstable angina and non-Q wave myocardial infarction: does the clinical diagnosis have therapeutic implications? J Am Coll Cardiol. 1999;33(1):107–118. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(98)00553-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sociedade Brasileira de Cardiologia Diretrizes sobre angina instável e infarto agudo do miocárdio sem supradesnível do segmento ST parte I: estratificação de risco e condutas nas primeiras 12 horas após a chegada do paciente ao hospital. Arq Bras Cardiol. 2001;77(supl 2):1–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sociedade Brasileira de Cardiologia Diretrizes sobre angina instável e infarto agudo do miocárdio sem supradesnível do segmento ST parte II: condutas nos pacientes de risco intermediário e alto . Arq Bras Cardiol. 2001;77(supl 2):23–37. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Anderson JL, Adams CD, Antman EM, Bridges CR, Califf RM, Casey DE, Jr, et al. American College of Cardiology. American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines (Writing Committee to Revise the 2002 Guidelines for the Management of Patients With Unstable Angina/Non ST-Elevation Myocardial Infarction) American College of Emergency Physicians. Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions. Society of Thoracic Surgeons. American Association of Cardiovascular and Pulmonary Rehabilitation. Society for Academic Emergency Medicine ACC/AHA 2007 guidelines for the management of patients with unstable angina/non ST-elevation myocardial infarction: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines (Writing Committee to Revise the 2002 Guidelines for the Management of Patients With Unstable Angina/Non ST-Elevation Myocardial Infarction): developed in collaboration with the American College of Emergency Physicians, the Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions, and the Society of Thoracic Surgeons: endorsed by the American Association of Cardiovascular and Pulmonary Rehabilitation and the Society for Academic Emergency Medicine. Circulation. 2007;116(7):e148–e304. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.181940. Erratum in Circulation. 2008;117(9):e180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.dos Santos ES, Timerman A, Baltar VT, Castillo MT, Pereira MP, Minuzzo L, et al. Escore de risco Dante Pazzanese para síndrome coronariana aguda sem supradesnivelamento do segmento ST. Arq Bras Cardiol. 2009;93(4):343–351. doi: 10.1590/s0066-782x2009001000006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Califf RM, Abdelmeguid AE, Kuntz RE, Popma JJ, Davidson CJ, Cohen EA, et al. Myonecrosis after revascularization procedures. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1998;31(2):241–251. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(97)00506-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zou KH, O'Malley AJ, Mauri L. Receiver-operating characteristic analysis for evaluating diagnostic tests and predictive models. Circulation. 2007;115(5):654–657. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.594929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Harrell FE, Jr, Califf RM, Pryor DB, Lee KL, Rosati RA. Evaluating the yield of medical tests. JAMA. 1982;247(18):2543–2546. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cannon CP. Evidence-based risk stratification to target therapies in acute coronary syndromes. Circulation. 2002;106(13):1588–1591. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000030416.80014.f4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Braunwald E, Jones RH, Mark DB, Brown J, Brown L, Cheitlin MD, et al. Diagnosing and managing unstable angina. Agency for Health Care Policy and Research. Circulation. 1994;90(1):613–622. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.90.1.613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Braunwald E, Antman EM, Beasley JW, Califf RM, Cheitlin MD, Hochman JS, et al. ACC/AHA guidelines for the management of patients with unstable angina and non-ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction. A report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines (Committee on the Management of Patients with Unstable Angina) J Am Coll Cardiol. 2000;36(3):970–1062. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(00)00889-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.White HD, Wong CK. Risk stratification and treatment benefits in patients with non-ST-elevation acute coronary syndromes. Eur Heart J. 2002;23(3):187–191. doi: 10.1053/euhj.2001.2904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Boersma E, Pieper KS, Steyerberg EW, Wilcox RG, Chang WC, Lee KL, et al. Predictors of outcome in patients with acute coronary syndromes without persistent ST-segment elevation: results from an international trial of 9461 patients. The PURSUIT Investigators. Circulation. 2000;101(22):2557–2567. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.101.22.2557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Eagle KA, Lim MJ, Dabbous OH, Pieper KS, Goldberg RJ, et al. Van de Werf F. A validated prediction model for all forms of acute coronary syndrome: estimating the risk of 6-month postdischarge death in an international registry. JAMA. 2004;291(22):2727–2733. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.22.2727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Granger CB, Goldberg RJ, Dabbous O, Pieper KS, Eagle KA, Cannon CP, et al. Global Registry of Acute Coronary Events Investigators Predictors of hospital mortality in the global registry of acute coronary events. Arch Intern Med. 2003;163(19):2345–2353. doi: 10.1001/archinte.163.19.2345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yusuf S. Design, baseline characteristics, and preliminary clinical results of the Organization to Assess Strategies for Ischemic Syndromes-2 (OASIS-2) trial. Am J Cardiol. 1999;84(5A):20M–25M. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(99)00549-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mattos LA. Racionalidade e métodos do registro ACCEPT - Registro Brasileiro da Prática Clínica nas Síndromes Coronarianas Agudas da Sociedade Brasileira de Cardiologia. Arq Bras Cardiol. 2011;97(2):94–99. doi: 10.1590/s0066-782x2011005000064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]