Abstract

Aims

To provide the first description and quantification of symptom changes during interstitial cystitis/bladder pain syndrome and chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome symptom exacerbations (“flares”).

Methods

Participants at one site of the Trans-Multidisciplinary Approaches to the study of chronic Pelvic Pain Epidemiology and Phenotyping Study completed two 10-day diaries over the one-year study follow-up period, one at baseline and one during their first flare (if not at baseline). On each day of the diary, participants reported whether they were currently experiencing a flare, defined as “symptoms that are much worse than usual” for at least one day, and their levels of urination-related pain, pelvic pain, urgency, and frequency on a scale of 0-10. Linear mixed models were used to calculate mean changes in symptoms between non-flare and flare days from the same participant.

Results

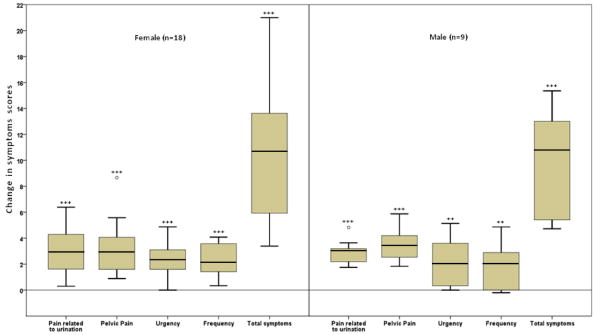

Eighteen of 27 women and 9 of 29 men reported at least one flare during follow-up, for a total of 281 non-flare and 210 flare days. Of these participants, 44.4% reported one flare, 29.6% reported two flares, and 25.9% reported ≥3 flares over the combined 20-day diary observation period, with reported flares ranging in duration from 1 day to >2 weeks. During these flares, each of the main symptoms worsened significantly by a mean of at least two points and total symptoms worsened by a mean of 11 points for both sexes (all p≤0.01).

Conclusions

Flares are common and correspond to a global worsening of urologic and pelvic pain symptoms.

Keywords: Interstitial cystitis, chronic prostatitis, symptom exacerbation, flare, bladder pain syndrome, chronic pelvic pain syndrome

Introduction

Although the natural history of interstitial cystitis/bladder pain syndrome (IC/BPS) and chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome (CP/CPPS) is widely believed to include symptom exacerbations (“flares”) (1-6), very few studies have investigated the causes of these flares (5, 7-19). Therefore, we took advantage of the one-year follow-up period of the prospective Trans-Multidisciplinary Approaches to the study of chronic Pelvic Pain (MAPP) Epidemiology and Phenotyping (EP) Study to embed a case-crossover study of flare etiology, including such possible triggers as diet, sexual activity, and urinary tract infections. For that study, we defined flares as “symptoms that are much worse than usual” based on clinical consensus because no published descriptive data were available on flares at the time of conception of our study – only one presumably clinician-derived definition (“increase in [IC] symptoms (frequency greater than 8 times in 24 hours, persistent urgency, and/or persistent pain), […] that persist for [>1] week” (1)). Two additional clinician-derived definitions have also since been published (“acute exacerbations of symptoms” (17), and increased symptoms by “[>50%] in terms of the [IC] Symptom Index, [IC] Problem Index, and visual analogue scale scores owing to breakthrough pain for [≥2] weeks” (20)). Finally, one subsequent online survey queried presumed IC/BPS patients and found that 19% described flares as a “period of extreme pain with increased urinary frequency/urgency across several days or weeks”; 12% as a “sudden increased intensity of symptoms”; 7% as a “dramatic increase in IC symptoms across several hours”; 5% as a “worsening of symptoms from baseline”; 4% as a “subtle worsening of symptoms”; and 52% as all of the above (21). However, beyond this one unpublished survey, no studies have described or quantified symptom changes during flares, particularly among patients with confirmed IC/BPS or those with CP/CPPS. As this information is critical for studying flare etiology and treatment, we conducted an exploratory investigation to describe and quantify symptom changes during flares among IC/BPS and CP/CPPS participants enrolled at one site of the multi-center Trans-MAPP EP Study.

Materials and Methods

Study design

The Trans-MAPP EP Study is a one-year, prospective observational study designed to characterize the treated natural history of IC/BPS and CP/CPPS, together referred to as urologic chronic pelvic pain syndromes (UCPPS), in order to identify subgroups of patients that may lead to a better understanding of the causes, clinical course, and treatment response in future clinical trials. The study consists of three in-clinic visits (baseline, 6-months, and 12-months), at which time participants complete a lengthy battery of questionnaires and provide biologic specimens, as well as shorter bi-weekly online assessments. All participants who meet the entry criteria outlined in Table 1 are eligible. Each participating site was asked initially to recruit 30 female and 30 male UCPPS participants.

Table 1.

Eligibility criteria for the Trans-Multidisciplinary Approaches to the study of Chronic Pelvic Pain (MAPP) Epidemiology and Phenotyping Study

| Inclusion criteria | |

| 1. | Has signed and dated the appropriate informed consent document: |

| a) Has agreed to participate in the Trans-MAPP Epidemiology and Phenotyping Study procedures. | |

| b) Has given permission for use of DNA for genes related to the main goals of the study. | |

| 2. | Is 18 years of age or older. |

| 3. | Reports a response of at least one on a 0-10 point scale assessing average pain, pressure, and discomfort associated with the bladder/prostate and/or pelvic region in the past two weeks. |

| 4. | (Interstitial cystitis/bladder pain syndrome (IC/BPS) criteria for female and male participants) Reports an unpleasant sensation of pain, pressure or discomfort perceived to be related to the bladder and/or pelvic region, associated with lower urinary tract symptoms. |

| a) These IC/BPS symptoms must have been present for the majority of the time during any three months in the previous six months and; | |

| b) These IC/BPS symptoms must have been present for the majority of the time during the most recent three months. | |

| 5. | (Chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome (CP/CPPS) criteria for male participants) Reports pain or discomfort in any of the following: perineum, testicles, tip of penis, below the waist, with urination, with ejaculation, with bladder filling, or relieved by voiding. |

| a) These CP/CPPS symptoms must have been present for the majority of the time during any three months in the previous six months.* | |

|

| |

| Exclusion criteria | |

|

| |

| 1. | Has an on-going symptomatic urethral stricture. |

| 2. | Has an on-going neurological disease or disorder affecting the bladder or bowel fistula. |

| 3. | Has a history of cystitis caused by tuberculosis, radiation therapy, or Cytoxan/cyclophosphamide therapy. |

| 4. | Has undergone augmentation cystoplasty or cystectomy. |

| 5. | Has an active autoimmune or infectious disorder (such as Crohn's disease or ulcerative colitis, lupus, rheumatoid arthritis, multiple sclerosis, or HIV). |

| 6. | Has a history of cancer (with the exception of skin cancer). |

| 7. | Has current major psychiatric disorder or other psychiatric or medical issues that would interfere with study participation (e.g., dementia, psychosis, upcoming major surgery, etc.). |

| 8. | Has severe cardiac, pulmonary, renal, or hepatic disease that, in the judgment of the study physician, would preclude participation in the study. |

| 9. | [Male participants only] Has been diagnosed with unilateral orchalgia without pelvic symptoms. |

| 10. | [Male participants only] Has a history of transurethral microwave thermotherapy (TUMT), transurethral needle ablation (TUNA), balloon dilation, prostate cryo-surgery, or laser procedure. |

|

| |

| Deferral criteria | |

|

| |

| 1. | If the potential participant has had definitive treatment for acute epidymitis, urethritis, or vaginitis, he/she will be deferred for at least three months from resolution of symptoms. |

| 2. | If the potential participant has a history of unevaluated hematuria, he/she will be deferred until the hematuria is evaluated. |

| 3. | If the potential participant has an abnormal dipstick urinalysis confirming abnormal levels of nitrites and has a positive 48 hour urine culture, he/she will be deferred for three months. |

| 4. | [Male participants only] If the potential participant has had a prostate biopsy or transurethral resection of the prostate (TURP) within the last three months, he will be deferred for three months following prostate biopsy or TURP. |

| 5. | [Female participants only] If the potential participant has a positive urine pregnancy test she will be deferred until after delivery. |

Although male CP/CPPS participants were not required to have had symptoms for the majority of the time during the most recent three months in the previous six months similar to the IC/BPS criteria, only two Washington University participants did not meet this additional criteria. Therefore, differences in eligibility criteria by syndrome and sex are unlikely to have influenced sex-based comparisons.

For the present study, we invited all participants enrolled at the Washington University site to complete two 10-day symptom diaries, the first at baseline and the second during their first flare. We did not ask participants to complete diaries during additional flares to avoid overburdening participants and disrupting the parent study. We designed our study based on the a priori clinical assumption that flares last at least one day and occur approximately once per year. Therefore, the baseline diary was intended to capture 10 days of non-flare symptoms and the second flare diary was intended to capture symptoms during flares lasting ≥1 day, as well as the duration of these flares. Over the course of the study, however, we observed that some participants experienced flares considerably more often than anticipated. For instance, some participants came to their baseline visit during a flare and some experienced a flare while completing their baseline diary. For participants who came to their baseline visit during a flare, we asked them to complete their flare diary first and then to complete their non-flare “baseline” diary once their flare had subsided. For those who experienced a flare while completing their baseline diary, we asked them to continue to complete their baseline diary for 10 days and then to proceed to their flare diary. Therefore, some participants provided 20 consecutive days of symptoms rather than two sets of 10 days of symptoms. Finally, over the course of the study, we also became aware that some participants experienced shorter flares than expected (i.e., flares lasting only minutes or hours rather than ≥1 day). Therefore, to maintain our focus on flares lasting ≥1 day, which are seen more commonly in clinical practice and are best described by a daily diary (rather than, for instance, an hourly diary), we instructed participants to complete the flare diary only when they experienced a flare lasting ≥1 day. We are exploring the full spectrum of flares from minutes to days in a separate cross-sectional survey querying each of these durations of flares (22).

This study was approved by the Washington University School of Medicine Institutional Review Board (IRB). The parent study was approved by the IRB at each participating institution and the data coordinating center. All participants provided written informed consent. This analysis includes participants enrolled from the start of the study (February, 2010) through August, 2012.

Symptom assessment

Diary questions were based on questionnaires administered in the parent study: the Brief Flare Risk Factor Questionnaire (a questionnaire developed for the case-crossover study); the Female and Male Genitourinary Pain Indices (GUPIs) (23); the Brief Pain Inventory (24); and 0-10 point scales for urgency and frequency (25). Specifically, on each day of the diary, we asked participants whether they were currently experiencing a flare of their urologic or pelvic pain symptoms, defined as “symptoms that are much worse than usual”, or whether they experienced flare symptoms earlier that day. We also asked participants to report their daily average levels of: 1) pain or burning during urination; 2) pain or discomfort as their bladder fills; 3) pain or discomfort relieved by urinating; 4) urgency; 5) frequency; and 6) pain or discomfort in several pelvic or genitourinary areas described in Tables 3 and 4. All questions were assessed on a scale of 0-10, and the pelvic/genitourinary pain questions were accompanied by sex-specific genital diagrams. Finally, on the first page of the flare diary, we asked participants whether that day was the first day of their flare and, if not, how long ago their flare started. Study coordinators instructed participants to complete their diaries at the end of each day.

Table 3.

Changes in urologic and pelvic pain symptoms during symptom flares for 18 female interstitial cystitis/bladder pain syndrome patients, Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis 2010-12

| Non-flare (n=198 days) | Flare (n=147 days) | Change between all non-flare and flare days | Change between non-flare/flare transitions† | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||

| Median (range)‡ | Mean (range)§ | Median (range)‡ | Mean (range)§ | Median (range)‡ | Mean (range)§ | Median (range)‡ | Mean (range)§ | |

| Pain or burning/discomfort:‖ | ||||||||

| During urination | 0.0 (0.0 – 4.5) |

1.5 (0.0 – 4.6) |

3.0 (0.0 – 9.0) |

3.2 (0.0 – 8.9) |

1.5 (0.0 – 6.5)*** |

1.7 (-0.5 – 6.2)*** |

1.5 (0.0 – 4.0)*** |

1.7 (0.0 – 4.0)*** |

| As the bladder fills | 1.2 (0.0 – 8.0) |

2.4 (0.0 – 8.1) |

5.0 (0.0 – 10.0) |

4.7 (0.0 – 10.0) |

2.8 (0.0 – 5.0)*** |

2.3 (0.0 – 5.0)*** |

1.5 (0.0 – 6.5)*** |

1.9 (0.0 – 6.2)*** |

| Relieved by urinating | 1.0 (0.0 – 9.0) |

1.9 (0.0 – 8.8) |

5.0 (0.0 – 10.0) |

4.3 (0.3 – 10.0) |

2.2 (0.0 – 7.0) *** |

2.3 (-0.2 – 6.4)*** |

2.0 (0.0 – 5.0)** |

1.7 (-0.2 – 5.0)*** |

| Related to urination†† |

1.5 (0.0 – 9.0) |

2.7 (0.0 – 8.9) |

6.2 (1.0 – 10.0) |

5.6 (1.2 – 10.0) |

3.2 (0.0 – 7.0)*** |

3.0 (0.3 – 6.4)*** |

2.0 (0.0 – 6.5)*** |

2.3 (0.0 – 6.2)*** |

| In the clitoris | 0.0 (0.0 – 4.5) |

1.4 (0.0 – 4.9) |

0.0 (0.0 – 9.5) |

1.6 (0.0 – 8.8) |

0.0 (-1.0 – 5.0)* |

0.3 (-0.6 – 3.9) |

0.0 (-1.0 – 3.0) |

0.5 (-1.0– 3.0)* |

| In the front of the vagina (including the urethra) | 0.0 (0.0 – 6.5) |

1.8 (0.0 – 6.2) |

2.8 (0.0 – 9.0) |

3.4 (0.0 – 8.7) |

1.5 (0.0 – 8.5)*** |

1.7 (0.0 – 8.7)*** |

1.0 (0.0 – 8.0)** |

1.6 (0.0 – 8.0)** |

| In the back of the vagina | 0.0 (0.0 – 3.0) |

1.0 (0.0 – 3.6) |

1.5 (0.0 – 9.0) |

2.0 (0.0 – 8.3) |

0.5 (-1.0 – 6.0)** |

1.0 (-1.4 – 4.7)* |

0.0 (-1.0 – 4.0)* |

0.4 (-1.0 – 4.0) |

| Deep inside the vagina | 0.0 (0.0 – 3.5) |

1.0 (0.0 – 4.4) |

3.0 (0.0 – 10.0) |

2.9 (0.0 – 8.8) |

2.0 (-3.0 – 7.0)** |

2.0 (-1.9 – 5.2)*** |

1.0 (0.0 – 4.0)** |

1.5 (0.0 – 4.0)*** |

| In the entrance to the vagina | 0.0 (0.0 – 3.5) |

1.1 (0.0 – 4.2) |

1.0 (0.0 – 10.0) |

2.3 (0.0 – 8.8) |

0.2 (-1.0 – 7.0)* |

1.2 (-0.9 – 7.2)** |

0.2 (0.0 – 7.0)** |

1.0 (0.0 – 7.0)** |

| In the area between the vagina and the rectum | 0.0 (0.0 – 2.5) |

0.4 (0.0 – 3.2) |

0.0 (0.0 – 7.0) |

0.7 (0.0 – 6.5) |

0.0 (-1.0 – 4.5) |

0.3 (-0.7 – 3.2) |

0.0 (-1.0 – 1.0) |

0.1 (-1.0 – 1.0) |

| Anywhere else below the waist and above the legs | 0.0 (0.0 – 9.0) |

1.8 (0.0 – 9.1) |

2.5 (0.0 – 10.0) |

3.0 (0.0 – 10.0) |

1.5 (-1.5 – 5.0)** |

1.2 (-1.4 – 5.8)** |

0.0 (0.0 – 2.0)* |

0.8 (-0.2 – 2.0)** |

| Anywhere in the pelvic region‡‡ |

1.8 (0.0 – 9.0) |

2.9 (0.0 – 9.1) |

5.2 (2.0 – 10.0) |

5.9 (1.9 – 10.0) |

2.5 (1.0 – 8.5)*** |

3.0 (0.9 – 8.7)*** |

1.5 (0.0 – 8.0)*** |

2.2 (0.0 – 8.0)*** |

| Urgency‖ |

2.5 (0.0 – 9.0) |

2.6 (0.0 – 8.9) |

5.0 (0.0 – 10.0) |

5.0 (0.0 – 10.0) |

2.2 (0.0 – 5.0)*** |

2.4 (0.0 – 4.9)*** |

1.0 (0.0 – 6.0)** |

1.6 (-0.6 – 6.2)** |

| Frequency‖ |

2.2 (0.0 – 10.0) |

3.2 (0.0 – 9.7) |

5.5 (1.0 – 10.0) |

5.4 (1.0 – 10.0) |

2.2 (0.0 – 5.0)*** |

2.2 (0.3 – 4.1)*** |

1.0 (0.0 – 3.0)** |

1.0 (0.0 – 3.0)** |

| Total symptoms‖§§ |

8.5 (0.0 – 37.0) |

11.2 (0.0 – 36.6) |

21.5 (5.0 – 40.0) |

21.9 (5.0 – 40.0) |

10.5 (3.0 – 20.0)*** |

10.7 (3.4 – 21.0)*** |

6.0 (1.0 – 19.5)*** |

7.1 (1.0 – 19.0)*** |

0.01 <p<0.05

0.001<p≤0.01

p≤ 0.001

Includes 43 non-flare/flare transition pairs.

Calculated as the median and range of participant-specific median scores.

The mean was calculated by linear mixed models and the range was calculated as the minimum and maximum of participant-specific mean values.

All symptoms were assessed on a scale of 0-10, except for total symptoms, which ranges from 0-40.

Defined as the maximum urination-related symptom score (pain/burning/discomfort during urination, as the bladder fills, and relieved by urinating) per day.

Defined as the maximum pelvic pain or discomfort symptom score (in the clitoris, in the front of the vagina (including the urethra), in the back of the vagina, deep inside the vagina, in the entrance to the vagina, in the area between the vagina and the rectum, and anywhere else below the waist and above the legs) per day.

Sum of daily pain related to urination, pelvic pain, urgency, and frequency.

Table 4.

Changes in urologic and pelvic pain symptoms during symptom flares for 9 male interstitial cystitis/bladder pain syndrome and/or chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome patients, Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis 2010-12

| Non-flare (n=83 days) | Flare (n=63 days) | Change between non-flare and flare days | Change between non-flare/flare transitions† | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||

| Median (range)‡ | Mean (range)§ | Median (range)‡ | Mean (range)§ | Median (range)‡ | Mean (range)§ | Median (range)‡ | Mean (range)§ | |

| Pain or burning/discomfort:‖ | ||||||||

| During urination | 1.0 (0.0 – 6.0) |

1.7 (0.0 – 4.9) |

4.0 (0.0 – 8.0) |

4.0 (0.0 – 7.8) |

2.5 (0.0 – 5.5)* |

2.4 (-0.1 – 4.8)** |

1.0 (0.0 – 3.0) |

1.4 (0.0 – 3.3)* |

| As the bladder fills | 1.0 (0.0 – 4.0) |

1.5 (0.0 – 4.0) |

3.5 (0.0 – 10.0) |

4.5 (0.0 – 8.4) |

2.0 (0.0 – 10.0)** |

3.0 (0.0 – 6.0)*** |

2.0 (-1.0 – 3.0)* |

1.6 (-1.0 – 3.0)** |

| Relieved by urinating | 1.0 (0.0 – 3.0) |

1.7 (0.0 – 3.5) |

3.0 (0.0 – 8.5) |

3.3 (0.0 – 7.6) |

2.0 (-0.5 – 7.0)* |

1.7 (-0.7 – 5.2)* |

2.0 (-1.0 – 3.0) |

1.2 (-1.0 – 2.5)* |

| Related to urination†† |

2.0 (0.0 – 7.0) |

2.5 (0.0 – 6.2) |

5.0 (2.5 – 10.0) |

5.8 (2.5 – 9.1) |

2.5 (2.0 – 5.5)** |

3.2 (1.8 – 4.8)*** |

2.0 (0.0 – 3.0)** |

1.8 (0.0 – 3.0)*** |

| In the tip of the penis | 1.0 (0.0 – 2.5) |

1.2 (0.0 – 2.9) |

1.0 (0.0 – 6.5) |

2.7 (0.0 – 6.6) |

0.0 (0.0 – 5.5) |

1.5 (-0.8 – 5.0)* |

1.0 (0.0 – 6.0) |

1.3 (0.0 – 4.3)* |

| In the shaft of the penis | 0.5 (0.0 – 7.0) |

0.9 (0.0 – 5.8) |

0.0 (0.0 – 10.0) |

2.4 (0.0 – 9.1) |

1.2 (0.0 – 4.0) |

1.5 (-0.3 – 3.3)* |

1.8 (0.0 – 5.0) |

1.5 (0.0 – 3.7)* |

| In the left testicle | 0.0 (0.0 – 3.0) |

0.8 (0.0 – 2.8) |

2.5 (0.0 – 7.0) |

2.7 (0.0 – 6.5) |

2.5 (0.0 – 4.0) |

1.9 (0.0 – 3.7)** |

2.0 (0.0 – 3.0) |

1.4 (0.0 – 2.3)** |

| In the right testicle | 0.0 (0.0 – 3.0) |

0.2 (0.0 – 2.8) |

0.0 (0.0 – 7.0) |

2.0 (0.0 – 6.9) |

0.5 (0.0 – 4.0) |

1.8 (0.0 – 4.1)** |

0.0 (0.0 – 3.0) |

1.3 (0.0 – 2.3)* |

| In the area between the testicles and the rectum | 0.0 (0.0 – 1.0) |

0.6 (0.0 – 2.0) |

0.0 (0.0 – 6.0) |

2.9 (0.0 – 5.5) |

0.0 (0.0 – 6.0) |

2.3 (0.0 – 4.9)** |

2.0 (-1.0 – 4.0) |

1.6 (-1.0 – 3.7) |

| Anywhere else below the waist and above the legs | 1.0 (0.0 – 8.0) |

1.3 (0.0 – 7.2) |

1.5 (0.0 – 10.0) |

3.4 (0.0 – 9.5) |

0.5 (0.0 – 6.0) |

2.1 (-0.8 – 5.9)** |

1.0 (-0.5 – 6.0) |

1.5 (-0.5 – 4.0) |

| Anywhere in the pelvic region‡‡ |

2.0 (1.0 – 8.0) |

2.7 (1.1 – 7.7) |

6.0 (4.0 – 10.0) |

6.2 (4.0 – 9.5) |

3.0 (2.0 – 6.0)** |

3.5 (1.8 – 5.9)*** |

2.0 (-0.5 – 6.0)** |

2.1 (-0.5 – 4.3)** |

| Urgency‖ |

1.0 (0.0 – 3.5) |

1.7 (0.0 – 3.8) |

4.0 (0.0 – 6.0) |

3.7 (0.0 – 6.1) |

2.0 (0.0 – 5.0)* |

2.1 (0.0 – 5.1)** |

1.5 (-0.5 – 5.0)* |

1.6 (-0.5 – 4.0)* |

| Frequency‖ |

1.0 (0.0 – 4.0) |

1.4 (0.0 – 3.5) |

3.5 (0.0 – 6.0) |

3.5 (0.0 – 6.0) |

1.5 (-0.5 – 6.0) |

2.1 (-0.2 – 4.9)** |

2.0 (0.0 – 4.0)* |

1.6 (0.0 – 3.3)** |

| Total symptoms‖§§ |

7.0 (1.0 – 19.5) |

8.2 (1.1 – 19.7) |

19.0 (8.0 – 27.0) |

19.0 (7.7 – 24.6) |

9.5 (4.0 – 16.5)** |

10.8 (4.7 – 15.4)*** |

6.0 (-0.5 – 18.0)** |

6.9 (-0.5 – 14.3)** |

0.01 <p<0.05

0.001<p≤0.01

p≤ 0.001

Includes 18 non-flare/flare transition pairs.

Calculated as the median and range of participant-specific median scores.

The mean was calculated by linear mixed models and the range was calculated as the minimum and maximum of participant-specific mean values.

All symptoms were assessed on a scale of 0-10, except for total symptoms, which ranges from 0-40.

Defined as the maximum urination-related symptom score (pain/burning/discomfort during urination, as the bladder fills, and relieved by urinating) per day.

Defined as the maximum pelvic pain or discomfort symptom score (tip of the penis, shaft of the penis, left testicle, right testicle, area between the testicles and the rectum, and anywhere else below the waist and above the legs) per day.

Sum of daily pain related to urination, pelvic pain, urgency, and frequency.

Statistical analysis

Before performing the analysis, we examined diaries for completeness and found it to be excellent for all symptoms examined (1.3-6.8% missing). However, for the initial current flare status question, a greater proportion of participants left this question blank (16.0% missing). As this question is key to the analysis, we imputed missing flare status from responses provided on the previous day (i.e., last observation carried forward). This imputation gave similar results as analyses using raw data (all differences ≤1.0); therefore, we presented imputed results throughout the manuscript.

To examine overall pain related to urination, we calculated daily participant-specific maximum levels of: 1) pain or burning during urination; 2) pain or discomfort with bladder filling; and 3) pain or discomfort relieved by urinating. We did the same for overall pelvic pain by taking the maximum value of pain in all genitourinary and pelvic areas. Finally, we calculated a total daily symptom score by summing the values for urination-related pain, pelvic pain, urgency, and frequency.

To investigate the change in symptoms during flares, we compared levels of symptoms on days when participants reported flares to those from the same participant on days when they did not report a flare. Therefore, only participants who provided symptom information on at least one non-flare and one flare day contributed to the analysis. As the data were frequently non-normally distributed, we first performed a crude, statistically conservative analysis by calculating participant-specific median flare and non-flare symptom values and comparing these values by the non-parametric Wilcoxon signed rank test. However, to take advantage of all data points provided by participants, we also compared mean flare and non-flare values using linear mixed models to account for multiple observations per participant. As some results from these two analyses differed in magnitude, we presented findings from both analyses.

Although not intended by the study design, several participants experienced one or more flares while completing their baseline diary, giving us the opportunity to perform a post-hoc analysis examining the initial change in symptoms that triggered participants to classify their symptoms as a flare. We performed these analyses in the same way as for comparisons of all flare and non-flare days within participants, and we included both flare-to-non-flare and non-flare-to-flare transition pairs because they gave similar results.

Finally, to examine whether participants with consistently high non-flare levels of symptoms attenuated our estimates for symptom change (as these participants have less “room” for change on a 0-10 point scale), we performed sensitivity analyses excluding participants who reported levels of ≥8 for any symptoms on non-flare days.

Results

Of the 29 female participants enrolled at our site, 27 (93.1%) completed at least one diary, and 18 (66.7% of those who completed a diary) reported a flare and provided information when they were not experiencing a flare, for a total of 198 non-flare and 147 flare days. For men, 29 of 31 (93.5%) participants completed at least one diary, 9 (31.0%) of whom reported a flare during follow-up, for a total of 83 non-flare and 63 flare days. Both female and male participants varied widely in age but tended to be Caucasian (Table 2). At study entry, women reported a longer duration of their condition than men. Participants' baseline symptom scores ranged from a median of 2.0-6.0 for individual symptoms and 6.0-12.0 for symptom indices. A similar proportion of women and men had non-urologic somatic syndromes.

Table 2.

Baseline characteristics of interstitial cystitis/bladder pain syndrome (IC/BPS) and chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome (CP/CPPS) patients, Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis 2010-12

| Female (n=18) |

Male (n=9) |

|

|---|---|---|

| Age (years, median (range)) | 56.5 (18.9 – 75.4) | 40.2 (28.6 – 62.8) |

| Caucasian (%) | 83.3 | 100 |

| Duration of symptoms (years, median (range)) | 13.8 (0.2 – 36.6) | 1.9 (0.9 – 5.4) |

| Baseline symptoms (median (range)): | ||

| Pelvic pain, pressure, or discomfort in the past two weeks (on a scale of 0-10) | 4.0 (2.0 – 10.0) | 5.0 (3.0 – 9.0) |

| Urgency in the past two weeks (on a scale of 0-10) | 6.0 (1.0 – 9.0) | 4.0 (0.0 – 8.0) |

| Frequency in the past two weeks (on a scale of 0-10) | 5.0 (1.0 – 9.0) | 2.0 (0.0 – 10.0) |

| Genitourinary pain index (on a scale of 0-23) | 12.0 (5.0 – 20.0) | 12.0 (5.0 – 20.0) |

| Interstitial cystitis symptom index (on a scale of 0-20) | 11.0 (0.0 – 17.0) | 8.0 (1.0 – 17.0) |

| Interstitial cystitis problem index (on a scale of 0-16) | 10.0 (3.0 – 15.0) | 6.0 (0.0 – 14.0) |

| Presence of non-urologic somatic syndromes (%):* | ||

| Irritable bowel syndrome | 27.8 | 33.3 |

| Fibromyalgia | 3.7 | 0.0 |

| Chronic fatigue syndrome | 22.2 | 0.0 |

| Any somatic syndrome | 38.9 | 33.3 |

Assessed by the Complex Medical Symptoms Inventory.

Female participants

Of the 18 women who reported a flare, five came to their baseline visit during a flare, seven experienced a flare within 10 days of baseline, and the remainder experienced at least one flare later during follow-up, ranging from 14-258 days after baseline. Over the course of follow-up and a maximum of 20 days of observation, 44.4% of participants experienced only one flare (which does not preclude flares outside of the 20-day observation period), 22.2% experienced two flares, and 33.3% experienced 3-4 flares. Flares ranged in duration from 1 day in the case of 22.2% of reported flares to ≥2 weeks in the case of one flare; the exact length of many flares could not be determined because the diary terminated before the end of the flare.

In general, female participants' reported low symptom scores when not experiencing a flare, with median or mean scores ranging from 0.0-3.2 on a scale of 0-10 for individual symptoms and 8.5-11.2 on a scale of 0-40 for all symptoms combined (Table 3 and Figure 1). Symptom scores were considerably higher during flares (0.0-6.2 for individual symptoms and 21.5-21.9 for overall symptoms). Comparing all non-flare and flare days from the same participant, symptom scores were significantly higher at the time of a flare by a median or mean of 0.2-3.2 points for all symptoms examined, except for pain in the area between the vagina and rectum, and possibly pain in the clitoris. Overall symptoms were significantly worse by 10.5-10.7 points.

Figure 1.

Changes in urologic and pelvic pain symptom scores during symptom flares among interstitial cystitis/bladder pain syndrome and chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome patients, Washington University School Medicine in St. Louis, 2010 – 2012.

Box plots of the change in urologic and pelvic pain symptom scores during symptom flares lasting ≥1 day are presented for 18 female interstitial cystitis/bladder pain syndrome (IC/BPS) and 9 IC/BPS or chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome patients. For each box plot, the lowest line represents the smallest value; the lower end of the box represents the 25th percentile; the line within the box represents the mean; the upper end of the box represents the 75th percentile; the upper line at the top of the whisker represents the largest value below the upper fence (the sum of the 75th percentile and 1.5 times the interquartile range (the difference between the 25th and 75th percentile)); and the circles represent values between the upper fence and the far upper fence (the sum of the 75th percentile and 3 times the interquartile range). Two asterisks denote statistically significant differences between non-flare and flare scores at p-values between 0.01 and 0.001 and three asterisks denote statistically significant differences between non-flare and flare scores at p-values less than or equal to 0.001.

In general, a similar pattern of symptom changes was observed for transition pairs as for comparisons of all non-flare and flare days. However, the magnitude of change was frequently smaller for transition pairs (median or mean=0.0-2.3 for individual symptoms and 6.0-7.1 for overall symptoms). Although this difference suggests that symptoms may increase before and during the first half of a flare and decrease in the second half and following a flare, we did not have sufficient power to investigate this hypothesis.

Male participants

Fewer men (n=9) reported a flare than women (p=0.0080). Of these men, four came to their baseline visit during a flare, three experienced a flare within 10 days of baseline, and two experienced at least one flare later during follow-up, ranging from 144-289 days after baseline. Over the course of 20 days of observation, 44.4% of participants reported one flare, 44.4% reported two flares, and 11.1% reported three flares. These flares ranged in duration from one day in the case of 14.3% of reported flares to >3 weeks in the case of one flare.

Similar to female participants, men reported generally low symptom scores when not experiencing a flare (mean or median score=0.0-2.7 for individual symptoms and 7.0-8.2 for all symptoms combined, Table 4 and Figure 1) and considerably higher symptom scores during flares (0.0-6.2 for individual symptoms and 19.0 for overall symptoms). Comparing all non-flare and flare days from the same participant, all symptoms worsened during flares (0.0-3.5 for individual symptoms and 9.5-10.8 for overall symptoms), although pain in specific genital areas and frequency were not significantly worse in more conservative Wilcoxon sign rank analyses. A similar pattern, but with smaller changes in symptoms, was observed when non-flare/flare transition pairs were examined.

For both sexes, similar or lesser results were observed in sensitivity analyses excluding participants who reported symptom levels ≥8 on non-flare days (data not shown), indicating that participants with high non-flare levels of symptoms did not attenuate findings.

Discussion

In this exploratory study of UCPPS flares, we found that participants' self-reported flares lasting ≥1 day corresponded to a global worsening of symptoms, including urination-related pain, pelvic pain, urgency, and frequency. Although this large global worsening of symptoms was expected, at least for pain, an unexpected finding was that some participants experienced flares considerably more often than once per year. Approximately 30% of participants who reported flares experienced two flares over the course of 20 days of observation, and 25.9% experienced ≥3 flares. Even participants who reported only one flare may have experienced additional flares outside of the 20-day observation period. In contrast to these participants, the remaining participants (55.0% of all participants or 45.0% of those who completed the parent study) did not complete a flare diary and were thus assumed not to have experienced a flare, although the possibility that some forgot to return their flare diary later during follow-up cannot be ruled out. A further unexpected anecdotal finding is that some participants experienced flares lasting <1 day, which we are exploring in a separate cross-sectional study (22).

Comparing participants by sex, both women and men reported significantly worse symptoms by approximately 10-11 points during flares. However, women were more likely to report flares than men (70.4% (including one woman who provided information on flare days only) versus 31.0%, p=0.0030). While one possible explanation for this difference may be that women were more compliant with study instructions than men, the observations that similar proportions of women and men completed at least one diary (93.1% versus 93.5%) and that a non-significantly greater proportion of women came to their baseline visit during a flare or experienced a flare while completing their baseline diary than men (48.1% (including one woman who provided information on flare days only) versus 24.1%, p=0.061) argue against this possibility as the sole explanation. Another unlikely explanation is confounding by syndrome duration because, although women had had their condition for a longer average period of time than men, no association was observed between syndrome duration and reporting a flare (p=0.41). No association was also observed by the presence of non-urologic somatic syndromes (p=0.78). Finally, a further possible explanation is that women may have been more likely to experience flares lasting ≥1 day (as opposed to shorter flares) than men. Indeed, in our second study designed to explore the full spectrum of flares among these same participants, we found that women were more likely to report days-long flares and less likely to report hours- or minutes-long flares than men (22).

In designing our diaries, we took care to ensure that diary questions were similar to those used in both the parent study and broader UCPPS field. However, as several of the questionnaires upon which we based our diaries included questions that could not be cued for daily values, we cannot compare our values for magnitude of change (10-11 points on a 0-40 point scale) directly to those found to be clinically meaningful on standard questionnaires. For instance, although a 7-point change on the GUPI 0-45 point scale predicts symptom change (23), we cannot compare our observed change of 10-11 points with this 7-point change because we could not cue all GUPI items for daily values nor include all items because of space constraints. Nevertheless, we feel that our observed change of 10-11 points is clinically meaningful because over 50% of participants in our separate study of flare duration reported being bothered “a lot” (the worst category of bother) by flares lasting most of or more than one day (Sutcliffe et al., in preparation).

A further consideration for interpreting the magnitude of symptom change during flares is the influence of medications. We did not ask participants to report their daily medication use nor whether they increased their dose or number of medications during flares. Therefore, our estimate of symptom change during flares likely reflects the lower bound of change, as it includes participants whose change may have been attenuated by increased medication use. Other limitations of our study include its small sample size and collection of only 20 days-worth of symptoms, which precluded more detailed investigations on the exact duration of flares, symptoms leading up to and following remission of flares, and identification of possible sub-groups of participants with smaller or larger magnitudes of symptom change during flares. Our study was also restricted to flares lasting ≥1 day, a limitation that we have addressed in our subsequent study (Sutcliffe et al, in preparation).

Conclusions

Although small in size, our exploratory, longitudinal study describes in detail and quantifies, for the first time, the change in common urologic and pelvic pain symptoms during UCPPS flares, which we found to be considerable (i.e., global worsening by 10-11 points). This information, together with additional, future descriptive research on flares, will provide the necessary foundation for investigating the causes and treatment for flares.

Acknowledgments

We thank our MAPP research coordinators, Rebecca Bristol and Vivien Gardner, for implementing the study; members of the MAPP Data Coordinating Center for managing the parent study data; Dr. John Kusek for critical review of this manuscript; the physicians and nurses within the Division of Urological Surgery for referring their patients to our study; and, most importantly, the participants for their participation.

This study was funded by NIDDK MAPP Research Network grant, NIH DK082315.

References

- 1.Whitmore KE. Self-care regimens for patients with interstitial cystitis. Urol Clin North Am. 1994 Feb;21(1):121–30. Epub 1994/02/01. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Metts JF. Interstitial cystitis: urgency and frequency syndrome. Am Fam Physician. 2001 Oct 1;64(7):1199–206. Epub 2001/10/17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hanno PM, Burks DA, Clemens JQ, Dmochowski RR, Erickson D, FitzGerald MP, et al. American Urological Association (AUA) guideline: Diagnosis and treatment of interstitial cystitis/bladder pain syndrome. American Urological Association. 2011 [Google Scholar]

- 4.Propert KJ, Schaeffer AJ, Brensinger CM, Kusek JW, Nyberg LM, Landis JR. A prospective study of interstitial cystitis: results of longitudinal followup of the interstitial cystitis data base cohort. The Interstitial Cystitis Data Base Study Group. J Urol. 2000 May;163(5):1434–9. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(05)67637-9. Epub 2001/02/07. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Alexander RB, Trissel D. Chronic prostatitis: results of an Internet survey. Urology. 1996 Oct;48(4):568–74. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(96)00234-8. Epub 1996/10/01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Propert KJ, McNaughton-Collins M, Leiby BE, O'Leary MP, Kusek JW, Litwin MS. A prospective study of symptoms and quality of life in men with chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome: the National Institutes of Health Chronic Prostatitis Cohort study. J Urol. 2006 Feb;175(2):619–23. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5347(05)00233-8. discussion 23. Epub 2006/01/13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gillespie L. Metabolic appraisal of the effects of dietary modification on hypersensitive bladder symptoms. Br J Urol. 1993 Sep;72(3):293–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410x.1993.tb00720.x. Epub 1993/09/01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Koziol JA. Epidemiology of interstitial cystitis. Urol Clin North Am. 1994 Feb;21(1):7–20. Epub 1994/02/01. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Moon TD, Hagen L, Heisey DM. Urinary symptomatology in younger men. Urology. 1997 Nov;50(5):700–3. doi: 10.1016/S0090-4295(97)00336-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lutgendorf SK, Kreder KJ, Rothrock NE, Ratliff TL, Zimmerman B. Stress and symptomatology in patients with interstitial cystitis: a laboratory stress model. J Urol. 2000 Oct;164(4):1265–9. Epub 2000/09/19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mehik A, Hellstrom P, Lukkarinen O, Sarpola A, Jarvelin M. Epidemiology of prostatitis in Finnish men: a population-based cross-sectional study. BJU international. 2000 Sep;86(4):443–8. doi: 10.1046/j.1464-410x.2000.00836.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rothrock NE, Lutgendorf SK, Kreder KJ, Ratliff TL, Zimmerman B. Daily stress and symptom exacerbation in interstitial cystitis patients. Urology. 2001 Jun;57(6 Suppl 1):122. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(01)01075-5. Epub 2001/05/30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shorter B, Lesser M, Moldwin RM, Kushner L. Effect of comestibles on symptoms of interstitial cystitis. J Urol. 2007 Jul;178(1):145–52. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2007.03.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hedelin H, Jonsson K. Chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome: symptoms are aggravated by cold and become less distressing with age and time. Scandinavian journal of urology and nephrology. 2007;41(6):516–20. doi: 10.1080/00365590701428517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stanford E, McMurphy C. There is a low incidence of recurrent bacteriuria in painful bladder syndrome/interstitial cystitis patients followed longitudinally. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2007 May;18(5):551–4. doi: 10.1007/s00192-006-0184-9. Epub 2006/10/13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Interstitial Cystitis Association. Quick survey. [Accessed March 30, 2012]; Available at: http://www.ichelp.org/Page.aspx?pid=524.

- 17.Nickel JC, Shoskes DA, Irvine-Bird K. Prevalence and impact of bacteriuria and/or urinary tract infection in interstitial cystitis/painful bladder syndrome. Urology. 2010 Oct;76(4):799–803. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2010.03.065. Epub 2010/06/25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bassaly R, Downes K, Hart S. Dietary consumption triggers in interstitial cystitis/bladder pain syndrome patients. Female pelvic medicine & reconstructive surgery. 2011 Jan;17(1):36–9. doi: 10.1097/SPV.0b013e3182044b5c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hedelin H, Jonsson K, Lundh D. Pain associated with the chronic pelvic pain syndrome is strongly related to the ambient temperature. Scandinavian journal of urology and nephrology. 2012 Aug;46(4):279–83. doi: 10.3109/00365599.2012.669404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jeong HJ. Effects of a short course of oral prednisolone in patients with bladder pain syndrome with fluctuating, worsening pain despite low-dose triple therapy. Int Neurourol J. 2012;16(4):175–80. doi: 10.5213/inj.2012.16.4.175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Interstitial Cystitis Association Web survey. How do you define an IC flare? [Accessed February 17, 2011];2009 Available at: http://www.ichelp.org/Page.aspx?pid=525.

- 22.Sutcliffe S, Colditz GA, Pakpahan R, Song D, Bristol R, Gardner V, et al. Frequency and duration spectrum of urologic chronic pelvic pain symptom flares. J Urol. 2012;187(4):e335. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Clemens JQ, Calhoun EA, Litwin MS, McNaughton-Collins M, Kusek JW, Crowley EM, et al. Validation of a modified National Institutes of Health chronic prostatitis symptom index to assess genitourinary pain in both men and women. Urology. 2009 Nov;74(5):983–7. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2009.06.078. quiz 7 e1-3. Epub 2009/10/06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cleeland CS, Ryan KM. Pain assessment: global use of the Brief Pain Inventory. Ann Acad Med Singapore. 1994 Mar;23(2):129–38. Epub 1994/03/01. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Foster HE, Jr, Hanno PM, Nickel JC, Payne CK, Mayer RD, Burks DA, et al. Effect of amitriptyline on symptoms in treatment naive patients with interstitial cystitis/painful bladder syndrome. J Urol. 2010 May;183(5):1853–8. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2009.12.106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]