Abstract

Although perceived discrimination has been associated with depressive symptoms among Hispanic adults, not all individuals who report discrimination will report elevated levels of depression. This study examined whether acculturation and religious coping would moderate the association between past-year perceived discrimination and depressive symptoms in a sample of 247 Mexican-American post-secondary vocational students (59.6 % males; mean age = 26.81). Results from hierarchical regression analyses indicated that perceived discrimination, positive religious coping, and negative religious coping were significantly associated with depressive symptoms. Further analyses indicated that positive religious coping moderated the perceived discrimination–depressive symptoms association. Students reporting using positive religious coping were protected from experiencing heightened levels of depressive symptoms when faced with discrimination. Acculturation was not directly associated with depressive symptoms nor did it function as a moderator. The salutary influences of positive religious coping for Mexican-American students are discussed. Study limitations and future directions for research are also discussed.

Keywords: Depressive symptoms, Mexican-Americans, Religious coping, Discrimination, Acculturation

Background

Although Hispanics are the fastest growing minority group in the United States, the Hispanic population still reports experiencing discrimination [1]. Experiences of discrimination are associated with negative health outcomes, including elevated rates of depressive symptoms [1]. Yet, not all Hispanics who experience discrimination will report elevated levels of depressive symptoms. Variability in outcome may result from factors that moderate (i.e., buffer or exacerbate) the impact of discrimination on depressive symptoms. The purpose of the present study was to examine the moderating roles of acculturation and religious coping in the association between past-year perceived discrimination and depressive symptoms among a sample of Mexican-American two-year post secondary vocational students.

Theoretical/Conceptual Framework

According to stress-buffering models [2], perceived social support can moderate the impact of certain stressors on negative health outcomes. Consistent with these models, negative and positive religious coping can moderate the association between perceived discrimination and depressive symptoms. Reliance upon religion as a coping mechanism may be particularly important for Hispanic adults, most considering themselves Christians who rely on spiritual figures (e.g., God, Jesus) to provide solace and guidance in times of stress [3]. Through positive religious coping, in which individuals believe that a deity helps them cope, a collaborative partnership with the deity may be formed [4]. Those high in religious coping may draw upon the collaborative relationship to deal with the stress associated with discrimination. Therefore, we hypothesized that positive religious coping would buffer the impact of perceived discrimination on depressive symptoms. Conversely, we expected negative religious coping, the belief that a divine other is responsible for the current stressful situation, would exacerbate the impact of discrimination on depressive symptoms as an individual may perceives the stress as a form of punishment or abandonment by the deity [4]. Similarly, level of acculturation may moderate the discrimination–depressive symptoms association. Because individuals high in acculturation can lose ethnic social relationships that once offered a form of social support in times of stress [5], we theorized that high acculturation would exacerbate the discrimination–depressive symptoms association.

Methods

Participants and Procedures

Participants were a convenience sample of 247 Mexican-American students, drawn from a larger study conducted in fall 2004 and spring 2005, at two two-year vocational colleges in Texas. Students were mostly males (58.7 %), 61 % were between 18 and 26 years of age (M = 26.81, SD = 8.46) and 79.8 % were enrolled full-time. The survey was self-administered in classes after approval was attained from the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of the university conducting the study, as well as from one of the colleges with an IRB.

Measures

The 20-item Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale [6] was used to assess depressive symptoms. Students indicated how often they experienced past-week symptoms from 1 (‘rarely or none of the time’) to 4 (‘most or all of the time’) on the following four subscales: somatic complaints, depressive affect, positive affect, and interpersonal problems. All items were averaged so that higher scores reflect higher levels of depressive symptoms (Cronbach’s alpha = .83).

The 17-item, General Ethnic Discrimination Scale [1] assessed the frequency of perceived discriminatory events at work, public places, and health care settings within the past year. Scores for items ranged from 1 (‘never’) to 6 (‘almost all of the time’) and all items were averaged with higher scores indicating a greater frequency of perceived discrimination (Cronbach’s alpha = .89).

The 12-item Short Acculturation Scale for Hispanics [7] measured acculturation. Eight items measured acculturation related to language and media use, and four items measured acculturation related to social relationships. All 12 items were averaged so that high scores reflect greater acculturation (Cronbach’s alpha = .90).

Five items from the Brief RCOPE [8] assessed how often students employed religious coping on a scale from 1 (‘a great deal’) to 4 (‘not at all’). Two items measured negative religious coping and three items measured positive religious coping. The items were averaged so that higher scores reflect higher levels of positive (Cronbach’s alpha = .86) and negative (Cronbach’s alpha = .59) religious coping.

Analysis

Hierarchical regression analyses were conducted to test if acculturation and religious coping moderated the association between discrimination and depressive symptoms. Students’ gender and age covariates were entered in Step 1 of the model, past-year perceived discrimination in Step 2, and the moderator variables of acculturation, and positive and negative religious coping were entered in Step 3. Three two-way interactions testing if acculturation, positive religious coping and/or negative religious coping would moderate the association between past-year perceived discrimination and depressive symptoms were entered into Step 4 in three separate models. All variables included in two-way interactions were centered to avoid multicollinearity [9].

Results

Descriptive statistics and zero order correlations for study variables are presented in Table 1. Results for hierarchical regressions are presented in Table 2. The overall main effects model (see Step 3) accounted for a small but significant portion of the variance in depressive symptoms (R2 = .10, F[6, 243] = 5.46, p < .001). Past-year perceived discrimination, positive religious coping, and negative religious coping were significantly associated with depressive symptoms. Individuals reporting higher levels of past-year perceived discrimination, less positive religious coping, and more negative religious coping reported heightened levels of depressive symptoms.

Table 1.

Descriptive and zero-order correlations

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Depressive symptoms | – | .194* | −.046 | −.182* | .206* |

| 2. Past-year discrimination | .194* | – | .197* | .023 | .261* |

| 3. Acculturation | −.046 | .197* | – | .035 | .065 |

| 4. Positive religious coping | −.182* | .023 | .035 | – | .130* |

| 5. Negative religious coping | .206* | .261 | .065 | .130* | – |

p < .05;

p < .01;

p < .001

Table 2.

Examining the direct and interactive associations of discrimination, acculturation, and religious coping to depressive symptoms among Mexican-American two-year vocational students (N = 247)

| Step 1 | Step 2 | Step 3 | Step 4 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | −.01 | −.04 | −.06 | |

| Age | −.08 | −.06 | −.04 | |

| Past-year discrimination | .20** | .17** | ||

| Acculturation | −.06 | |||

| Positive religious coping | −.21*** | |||

| Negative religious coping | .20** | |||

| Discrimination × Acculturation | .12 | |||

| Discrimination × Positive religious coping | −.15* | |||

| Discrimination × Negative religious coping | −.05 | |||

| R2 | −.00 | .04 | .10 | |

| F-statistic for change in R2 | .76 | 3.94** | 5.46*** |

Interaction terms were entered individually in separate models in the presence of all main effects

p < .05;

p < .01;

p < .001

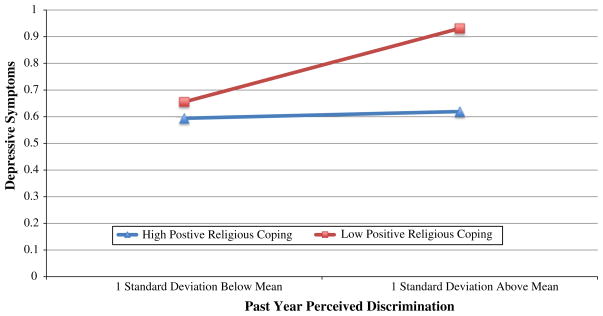

One of the three two-way interactions was significant (discrimination × positive religious coping), accounting for a small but significant portion of the variance (R2 = .02, F[1,243] = 5.58, p< .05) in depressive symptoms. Probing the interaction using the methods outlined by Aiken and West [9], indicated that the relationship between past-year perceived discrimination and depressive symptoms was significant at low levels of positive religious coping (β = .33, p < .001), but not a high levels (β = .03, p = .71); see Fig. 1. These results indicate the positive religious coping buffered the impact of perceived discrimination on Mexican-American students’ depressive symptoms.

Fig. 1.

Examining the past-year discrimination × positive religious coping interaction

Discussion

Consistent with stress-buffering models [2], results from this study indicate that positive religious coping moderates the relationship between past-year perceived discrimination and Mexican-American adults’ depressive symptoms. Individuals experiencing elevated levels of discrimination may turn to a spiritual figure to understand and make sense of the situation [4], and for this reason may escape elevated levels of depressive symptoms. Religious coping may be particularly relevant to Mexican-origin individuals, compared to the majority population, because of limited economic resources and access to other forms of coping, such as professional counseling [2]. Similarly, a majority of lower income individuals find religion beneficial when coping [4, 10]. Considering that more than 50 % of individuals attaining a sub-baccalaureate degree fall into lower income brackets, religious coping may be particularly important for our sample of vocational students as well.

Although religious involvement is important to the Mexican-American population, the amount of literature examining religiousness and its influence on discrimination in this population is scarce. One exception is a study done with Mexican-origin adults, in which religious attendance was found to moderate the association between discrimination and depressive symptoms [3]. The current study extends this prior research by indicating that the moderating effects of religiousness are not limited to organizational religious attendance. Rather, findings indicate that personal forms of spirituality can offset or buffer the association between perceived discrimination and depressive symptoms. Although negative religious coping did not moderate the association between past-year perceived discrimination and Mexican-American adults’ depressive symptoms, it was positively associated with depressive symptoms. Those who use negative religious coping methods may interpret stressful situations as a form of punishment or abandonment from God [4] and for this reason experience elevated levels of depressive symptoms.

Unlike religious coping, acculturation was not associated with depressive symptoms either directly or as a buffer of the perceived discrimination effects. Although inconsistent with our hypothesis, this finding is not completely unexpected given that the role of acculturation in mental health outcomes has produced mixed findings [5]. Mixed findings could be attributed to varying ways of measuring acculturation. Another possibility for null findings is that measurements of high versus low levels of acculturation no longer adequately represent the process individuals undergo when entering this country. Rather, future studies should measure acculturation in a way that represents biculturality, or balance between marginalization and assimilation.

Study findings must be considered in the context of certain limitations. First, the data for this study were cross-sectional, decreasing our ability to determine directionality between study variables. Secondly, data were drawn from a convenience sample of students from two Texas vocational schools, therefore generalizability may be limited. Finally, foreign-born status could not be determined for this sample, yet differences in foreign-born status could have significant effects on acculturation status and/or perceived discrimination. Future longitudinal studies that consider the role of foreign-born status and that are conducted in various regions of the country are needed to establish moderators of the associations between past-year perceived discrimination and Mexican-American adults’ depressive symptoms.

Conclusion

Despite study limitations, findings from this study indicate that positive religious coping is an important moderator of discrimination effects reported by Mexican-American individuals. Given its moderating role, religious coping would be beneficial to incorporate in mental health interventions with Mexican-Americans. This is particularly important considering the disparities faced by this population may lead to limited access to mental health resources, which could ultimately increase governmental healthcare costs.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by Grant #R03CA130589 from the National Cancer Institute, awarded to the second author.

Contributor Information

Alejandra Fernandez, Email: alejandra.fernandez@utexas.edu, Department of Kinesiology and Health Education, The University of Texas at Austin, 1 University Station, D3700, Austin, TX 78712, USA.

Alexandra Loukas, Email: alexandra.loukas@austin.utexas.edu, Department of Kinesiology and Health Education, The University of Texas at Austin, 1 University Station, D3700, Austin, TX 78712, USA.

References

- 1.Landrine H, Klonoff EA, Corral I, Fernandez S, Roesch S. Conceptualizing and measuring ethnic discrimination in health research. J Behav Med. 2006;29:79. doi: 10.1007/s10865-005-9029-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cohen S, Wills TA. Stress, social support, and the buffering hypothesis. Psychol Bull. 1985;98:310. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ellison CG, Finch BK, Ryan DN, Salinas JJ. Religious involvement and depressive symptoms among Mexican-origin adults in California. J Community Psychol. 2009;37:171. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pargament KI. The psychology of religion and coping: theory, research, practice. New York: The Guilford Press; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rivera FI. Contextualizing the experience of young Latino adults: acculturation, social support and depression. J Immigr Minor Health. 2007;9:237. doi: 10.1007/s10903-006-9034-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Radloff LS. The CES-D scale: a self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Appl Psychol Meas. 1977;1:385. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Marin G, Sabogal F, Marin BV, Otero-Sabogal R, Perez-Stable EJ. Development of a short acculturation scale for Hispanics. Hispanic J Behav Sci. 1987;9:183. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pargament K, Feuille M, Burdzy D. Brief RCOPE: current psychometric status of a short measure of religious coping. Religion. 2011;2:51. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Aiken LS, West SG. Multiple regression: testing and interpreting interactions. Newbury Park: Sage; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bailey TR, Leinbach DT, Scott M, Alfonso M, Kienzl GS, Kennedy B, et al. The characteristics of occupational sub-baccalaureate students entering the new millennium. Washington: National Assessment of Vocational Education, US Department of Education; 2003. [Google Scholar]