Abstract

The explicit polarization (X-Pol) theory is a fragment-based quantum chemical method that explicitly models the internal electronic polarization and intermolecular interactions of a chemical system. X-Pol theory provides a framework to construct a quantum mechanical force field, which we have extended to liquid hydrogen fluoride (HF) in this work. The parameterization, called XPHF, is built upon the same formalism introduced for the XP3P model of liquid water, which is based on the polarized molecular orbital (PMO) semiempirical quantum chemistry method and the dipole-preserving polarization consistent point charge model. We introduce a fluorine parameter set for PMO, and find good agreement for various gas-phase results of small HF clusters compared to experiments and ab initio calculations at the M06-2X/MG3S level of theory. In addition, the XPHF model shows reasonable agreement with experiments for a variety of structural and thermodynamic properties in the liquid state, including radial distribution functions, interaction energies, diffusion coefficients, and densities at various state points.

INTRODUCTION

Hydrogen fluoride (HF) is a highly corrosive and toxic compound with a boiling point temperature of 19.5 °C at atmospheric pressure.1 It is commonly used in industrial applications such as glass etching, where it reacts with silicon dioxide to produce hexafluorosilic acid2

| (1) |

Although progress has been made,1, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14 the amount of experimental data concerning the structure and physical properties of HF is scarce in comparison to other simple fluids of small molecules, due to experimental difficulties. As a result, there is great interest in developing computational models for HF, which can produce accurate dynamic and thermodynamic properties across a wide range of temperatures and pressures.

The first computational studies of HF in the liquid state date back to the works of Cournoyer and Jorgensen15, 16, 17 and the works of Klein and McDonald.18, 19 The approach of Cournoyer and Jorgensen, used in Monte Carlo simulations of the liquid, employed a pairwise 12-6-3-1 interaction potential between rigid monomers of the gas-phase geometry. The potential function was fitted to reproduce binding energies of molecular complexes from ab initio Hartree-Fock theory20, 21 using the STO-3G22 and 6-31G23 basis sets. Similarly, Klein and McDonald used molecular dynamics simulations to model the liquid state, in which a mixture of exponential and inverse power functions were parameterized to reproduce ab initio energies of the HF dimer.24

Both groups employed three-site models in their studies, but did not make use of condensed phase experimental data in their parameterizations. In 1984, Cournoyer and Jorgensen introduced the three-site TIPS model for liquid HF,25 which greatly improved the accuracy of computed thermodynamic properties of the liquid state as compared to experiment.3, 4, 5 The following year, the first neutron diffraction study of deuterium fluoride (DF) was published,6 providing structural information, including radial distribution functions at 293 K. A direct comparison to predictions from the TIPS model was provided in that study, showing TIPS to be surprisingly accurate at 293 K.

In 1997, two three-site models for liquid HF were introduced by Jedlovszky and Vallauri,26, 27 which consisted of a non-polarizable potential called JV-NP and a polarizable alternative called JV-P. Both models employed the experimental H–F bond length of 0.973 Å, determined by electron diffraction in the vapor phase.12 This was a departure from previous models, which employed a H–F bond length of 0.917 Å for the monomer in the gas phase.11 In 2000, a more extensive set of experimental data for two liquid and four supercritical states of DF was reported by Pfleiderer and co-workers,7 followed by simulations using the TIPS, JV-NP, and JV-P potentials. Comparison with the new experimental data revealed that the polarizable JV-P model was clearly superior compared to the non-polarizable potentials.28

In 2003, Wierzchowski, Kofke, and Gao introduced a quantum mechanical potential for liquid HF, which incorporated electronic polarization directly in the molecular wave function.29 This method, which was initially called a molecular orbital derived empirical potential for liquids (MODEL),30, 31 has been subsequently called the explicit polarization (X-Pol) theory,32, 33, 34 and has been used in studies of liquid water35 and a molecular dynamics simulation of a solvated protein.36 In the study of Wierzchowski et al.29 (henceforth referred to as the previous study), the semiempirical AM1 model37 was used to represent the individual monomers in the liquid, and the polarization of the molecular wave function of each HF molecule by the surrounding monomers was directly incorporated into the one-electron Hamiltonian. To account for short-range exchange-repulsion and long-range dispersion interactions, Lennard-Jones terms were used. Parameters for both the H–F bond lengths of 0.917 Å and 0.973 Å were provided. However, the simulation results indicated that the AM1 model was not sufficiently polarized for liquid HF.

In 2005, Kreitmeir et al. showed that thermodynamic properties were improved under the JV-NP model if a bond length of 0.950 Å was used.38 This observation led to a reparameterization of the JV-P model by Pártay, Jedlovszky, and Vallauri, called PJV-P, resulting in an optimized bond length of 0.930 Å.39 Pártay and co-workers provided an extensive comparison of the PJV-P model with several other models for liquid HF at many different states. Additionally, comparisons were made for 11 different state points using the newly available experimental results of McLain and co-workers.8, 9

Recent years have seen several studies using ab initio molecular dynamics (AIMD) techniques, including Born-Oppenheimer MD (BOMD) and Car-Parrinello MD (CPMD),40 to simulate the vapor and liquid phases of HF.41, 42, 43, 44, 45 In these studies, density functional theory (DFT) with the BLYP exchange-correlation functional,46, 47 which is known to lack an adequate description of dispersion effects, is typically used. The AIMD studies have shown that although HF monomers are flexible, dissociation of HF does not occur in the anhydrous liquid, agreeing with experiments.41 However, results from these simulations, even with the inclusion of dispersion corrections, have not been on the level of accuracy of the empirical models, such as PJV-P and JV-P, and have produced densities that are siginificantly higher than those observed experimentally, leading McGrath et al. to conclude that BLYP with the D2 dispersion correction48 is unsatisfactory for describing HF.45

While the modeling of liquid water by X-Pol under the AM1 method with Mulliken charges to represent the intermolecular electrostatic potential yielded accurate thermodynamic results,31 a similar attempt in the previous study at modeling liquid HF was not as fruitful.29 However, the previous study recognized that the H–F bond length could greatly affect the simulation results and should be considered as a parameter in the potential function optimization if a rigid model was used, which was not attempted in any HF model until a few years later. Additionally, it was noted that the AM1 method yielded poor molecular polarizability and that the Mulliken population charges used for polarization were too small.

The explicit polarization model for hydrogen fluoride introduced here seeks to improve upon the previous X-Pol study by employing a better treatment of polarization effects. Although studies employing path integral simulations have shown that structural and thermodynamic results can be improved from first principles molecular dynamics trajectories,49, 50 nuclear quantum effects are not explicitly treated in the present study. As in earlier quantum studies of HF,29, 43 a two-site monomer is used in the X-Pol model for HF (XPHF), as opposed to the more common three-site approach in classical models. In the present study, we employ the “semiempirical” polarized molecular orbital (PMO) method,51, 52, 53 by introducing a set of p-orbitals onto the hydrogen atom. The performance of the PMO model on molecular polarization and hydrogen-bonding is significantly improved over existing semiempirical models. The PMO Hamiltonian has been successfully used to develop a quantum mechanical force field within the X-Pol framework for liquid water called XP3P.35 In addition, we have employed an alternative population analysis for calculating partial charges, called the dipole-preserving polarization consistent (DPPC) charge method,54 which reproduces the total molecular dipole moment of each monomer from quantum mechanical calculations, eliminating the need for the charge scaling parameter in previous X-Pol simulations. Finally, the model has been parameterized using experimental data not available at the time of the previous study,8, 9 and has employed the optimized H–F bond length of 0.930 Å.39

In this work, a set of parameters for fluorine is incorporated into the PMO method, originally developed for oxygen and hydrogen containing compounds. These parameters were optimized by fitting against experimental and ab initio data on the HF monomer, HF dimer, HF trimer, (HF)(H2O) complex, and OF2. In the present study, the PMO formalism is identical to that of the XP3P model for liquid water. As in the case of XP3P, the XPHF method has been implemented into the MCSOL Monte Carlo program55 and a modified version of NAMD.56

SEMIEMPIRICAL PMO METHOD FOR HYDROGEN FLUORIDE

Polarized molecular orbital method

The PMO method is based on the formalisms of the MNDO method,57 which makes use of the neglect of diatomic differential overlap approximation (NDDO).58, 59 Three key modifications were introduced in PMO. Since the method has been reported in detail previously,35, 51, 52, 53 we only provide a brief summary of its key departures from MNDO.

First, a set of p-orbitals is introduced on the hydrogen atom. The addition of the p-orbitals greatly improves the performance on calculated molecular polarizabilities for a range of compounds, and provides an excellent description of hydrogen-bonding interactions. To prevent unphysical bonding interactions from the additional p-orbitals, the resonance integrals involving hydrogen are damped (Eqs. 2, 3),

| (2) |

| (3) |

where Slp of is the overlap integral ⟨Fl|Hp⟩ between a fluorine-centered orbital with angular momentum quantum number l and a hydrogen p-orbital. In the more general case that this integral needs to be evaluated for homonuclear pairs (e.g., ⟨Fl|Fl⟩), the specialized ζPMO exponents are used.

Second, the nucleus-electron attraction integral, , between the electronic charge density of atom A and the nucleus of atom B, is evaluated by the two-electron repulsion integral ⟨μAνA|sBsB⟩,57, 60 where sB denotes an s-orbital on nucleus B.59 This attraction integral is modified in the PMO model when both A and B are hydrogen atoms (Eq. 4),

| (4) |

The third and final departure from MNDO is concerned with core-core interactions. Similar to homonuclear overlap integrals, special exponents are used for homonuclear core-core repulsion. In addition, as is commonly used in DFT, the pairwise D1 dispersion correction of Grimme61 is used between all atom pairs.

At present, three different variations of the PMO method have been reported, PMOv1,52 PMO2,53 and PMOw,35 none of which contain parameters for fluorine. The variant of PMO for which we have decided to introduce the F parameters is the PMOw model, having kept all other parameters fixed to those reported in Ref. 35.

Motivation for using PMOw

A reasonable starting point for parameterization of empirical models for vapor and liquid phase simulations is an accurate description of dimer interactions. Here, the PMOw model has been parameterized with the goal of accurately describing the HF dimer, as well as other HF clusters.

As a motivation for introducing a new PMOw parameter set for F, we performed several single-point energy calculations and geometry optimizations on the HF dimer using the MOPAC62 software with the NDDO-type MNDO,57 AM1,37 RM1,63 PM3,64 and PM665 semiempirical methods. Interaction energies for fixed F-F distances with optimized H coordinates for each method were tabulated. In addition to the MOPAC calculations, analogous PMOw and ab initio calculations at the M06-2X/MG3S level66, 67, 68 were performed with an in-house code69 and NWChem version 5.1.1,70 respectively.

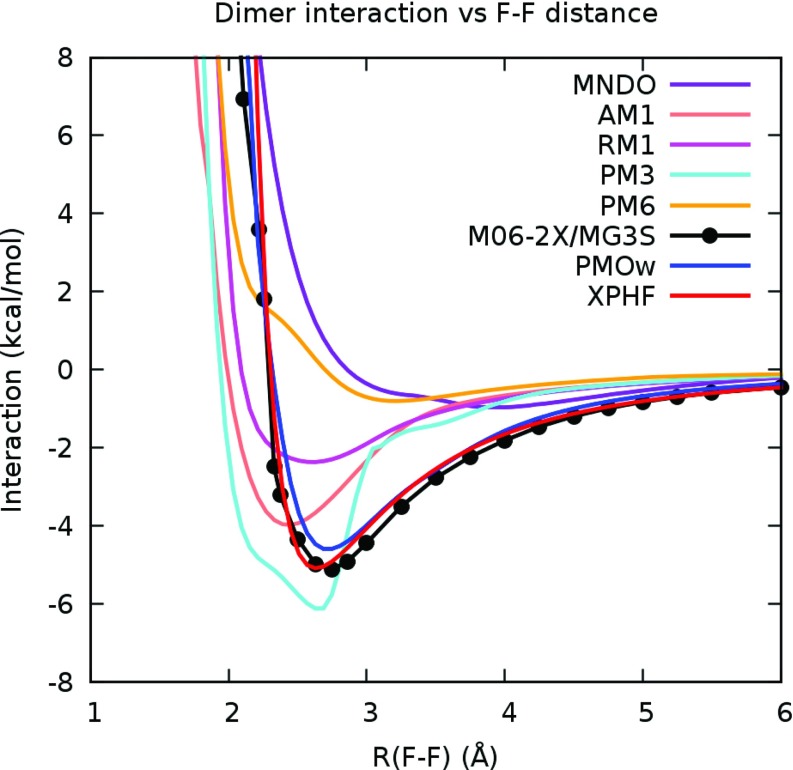

This series of calculations showed that with the exception of the PM3 method, all existing semiempirical methods produced geometries for the HF dimer that is qualitatively incorrect in comparison with experimental and M06-2X/MG3S results (Figure 1). In addition, these methods failed to accurately reproduce the interaction energy profile for the HF dimer (Figure 2). The minimum interaction energy is −4.54 kcal/mol with F-F distance 2.72 Å from experiment,13, 71 −4.94 kcal/mol with F-F distance 2.7316 Å at the CCSD(T)/TZ2P(f,d) level,72 and −5.13 kcal/mol with F-F distance 2.7242 Å at the M06-2X/MG3S level.

Figure 1.

Optimized HF dimers using several NDDO-type semiempirical methods, PMOw, DFT at the M06-2X/MG3S level, and that measured from experiment.13 All non-PMOw semiempirical dimers, with the exception of the PM3 optimized geometry, exhibit a qualitatively incorrect structure compared to ab initio and experimental results.

Figure 2.

Interaction energy profile of optimized HF dimers with respect to F-F distance for several NDDO-type semiempirical methods, PMOw, XPHF, and DFT at the M06-2X/MG3S level. Notice the odd behavior of the interaction energy curve for PM3, which produced a qualitatively correct optimized HF dimer geometry.

It is worth noting that although the PM3 optimized geometry appears qualitatively correct, the HF dimer interaction energy profile was found to be qualitatively incorrect. Thus, none of the existing NDDO-type semiempirical methods tested are adequate for accurately describing the HF dimer interaction.

Fluorine parameters for PMOw

The poor HF dimer descriptions of existing semiempirical methods and the success of the PMOw-based XP3P water model led to the decision to include fluorine in the PMOw model in connection with the original parameters for O and H modeling fluorine-containing compounds. The parameters for F in PMOw were obtained from the minimization of a fitness function that was defined as a weighted sum of the absolute differences for properties of the HF monomer, HF dimer, HF trimer, (HF)(H2O) complex, and OF2 molecule; these properties included length, bond angle, dipole moment, and interaction energies of optimized geometries.

Target values for the fitness function were set to experimental values where available and to ab initio derived values when experimental data were absent. Minimization of the fitness function was performed using stochastic optimization, starting from the RM1 parameter for F63 and the PMOw specific parameters for O as the initial guess with Asp and App held fixed. All previous parameters of PMOw for H and O were kept fixed to ensure that the PMOw results for water remained reproducible. The results of the optimized parameters are listed in Table 1, where the columns for H and O are reproduced from Ref. 35.

Table 1.

Parameters in the PMOw model. The parameters for F were obtained by stochastic optimization starting from the RM1 parameter for F using a fitness function related to experimental and ab initio calculated quantities of HF, (HF)2, (HF)3, (HF)(H2O), and OF2. The parameters for H and O were taken from Ref. 35.

| H | O | F | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Uss (eV) | −11.15043 | −111.86028 | −139.42406 |

| Upp (eV) | −7.35459 | −78.64105 | −109.03911 |

| βs (eV) | −6.88125 | −25.57063 | −69.32684 |

| βp (eV) | −3.52628 | −31.90404 | −34.08908 |

| ζs (Bohr−1) | 1.17236 | 3.05303 | 5.60791 |

| ζp (Bohr−1) | 1.05333 | 3.12265 | 3.11602 |

| α (Å−1) | 3.05440 | 3.76880 | 4.29492 |

| gss (eV) | 12.73667 | 17.36659 | 16.39526 |

| gsp (eV) | 8.04688 | 13.37288 | 18.38443 |

| gpp (eV) | 6.98401 | 14.78196 | 16.67384 |

| (eV) | 10.65161 | 13.49319 | 14.77192 |

| hsp (eV) | 1.92149 | 4.42643 | 4.30118 |

| (Å−1) | 2.52552 | 3.03253 | 3.48493 |

| ζPMO (Bohr−1) | 1.280 | 2.764 | 2.786 |

| Asp | NA | 0.03 | 0.03 |

| App | NA | 0.15 | 0.15 |

| κsp (Å−1) | NA | 0.47069 | 0.48605 |

| κpp (Å−1) | NA | 0.47069 | 0.38879 |

Hydrogen fluoride clusters

We tested our PMOw parameter set for F on a series of cyclic HF clusters from the trimer to the octamer as well as the monomer and dimer. We now present a comparison to experimental results where available, previously published ab initio data, and additional DFT calculations at the M06-2X level with the MG3S basis set.

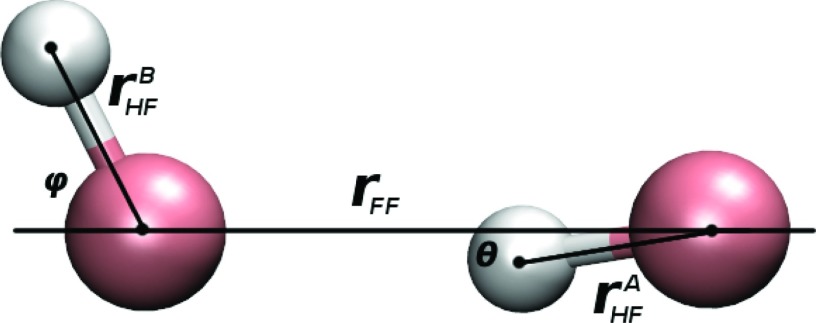

Table 2 lists bond lengths, angles, and dipole moments of the HF monomer and dimer at the PMOw, M06-2X/MG3S, and CCSD(T)/TZ2P(f,d) levels of theory as well as corresponding experimental values. The definitions for lengths and angles in Table 2 are shown in Figure 3. The experimental results of Table 2 are the same values used in the training set for parameterization of F.

Table 2.

HF monomer properties of PMOw compared to ab initio and experimental results.

| PMOw | M06-2X/MG3S | CCSD(T)/TZ2P(f,d) | Expt. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HF | ||||

| rHF (Å) | 0.917 | 0.918 | 0.9181 | 0.9172 |

| μ (Debye) | 1.80 | 1.88 | 1.821 | 1.803 |

| (HF)2 | ||||

| Eint (kcal/mol) | −4.64 | −5.13 | −4.941 | −4.544 |

| (Å) | 0.925 | 0.924 | 0.9231 | – |

| (Å) | 0.924 | 0.921 | 0.9211 | – |

| rFF (Å) | 2.72 | 2.72 | 2.731 | 2.72 ± 0.035 |

| θ (°) | 8.5 | 11.3 | 6.41 | 10 ± 65 |

| ϕ (°) | 67.3 | 71.8 | 68.81 | 63 ± 65 |

| μ (Debye) | 3.27 | 3.26 | 3.331 | 2.995 |

Figure 3.

Labeled quantities for the HF dimer corresponding to quantities given in Table 2.

The optimized HF monomer bond length and dipole moment from PMOw are 0.917 Å and 1.80 Debye, respectively, showing excellent agreement with the experimental values of 0.917 Å11 and 1.80 Debye.10 The F-F separation of the optimized dimer structure using PMOw was 2.72 Å, in good accord with the experimental value of 2.72 ± 0.03 Å. The optimized tilt (θ) and flap (ϕ) angles of 8.5° and 67.3° for the dimer fall within the uncertainty range of the experimental data 10° ± 6° and 63° ± 6°,13 respectively. The computed binding energy was −4.64 kcal/mol for the HF dimer and the corresponding total dipole moment was 3.26 Debye, which is in agreement with the CCSD(T)/TZ2P(f,d) results of −4.94 kcal/mol and 3.33 Debye.72 The corresponding experimental dipole moment has been reported to be 2.99 Debye.13

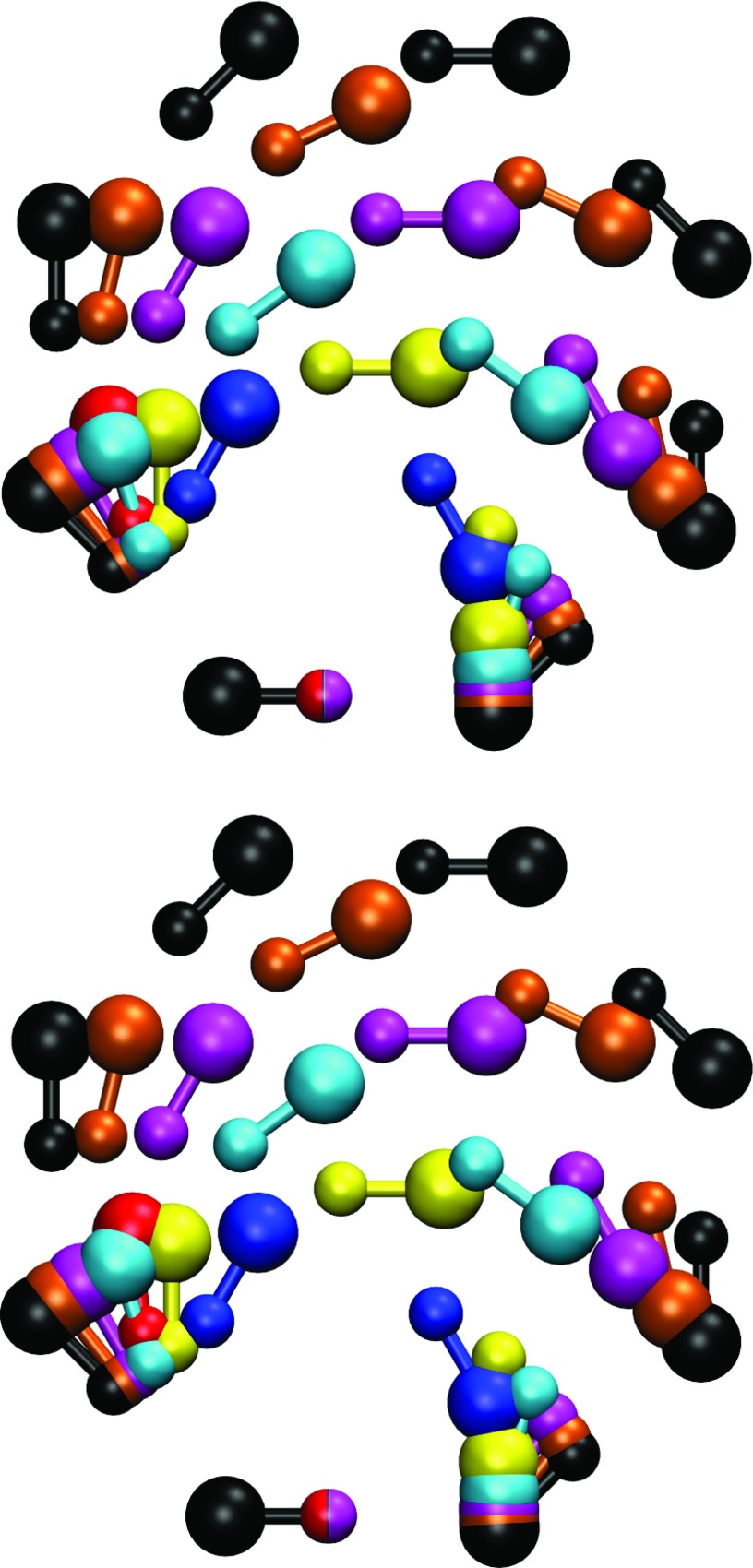

The results of geometry optimization on the larger clusters (HF)n for n = 3, ⋅⋅⋅, 8 using PMOw and M06-2X/MG3S along with the “best estimates” of Maerker and co-workers73 are given in Table 3. The quantities listed in the table are labeled in Figure 4 for the trimer, and are similar for larger clusters. As in the case of the monomer and dimer, the trimer was included in the parameterization training set, and the optimized properties are in good agreement with the M06-2X/MG3S results and Maerker's data set. Overall, the larger clusters, which were not included in the training set, also exhibit good agreement between PMOw, M06-2X/MG3S, and the “best estimates.” Figure 5 illustrates the cyclic clusters obtained from geometry optimization using PMOw and M06-2X/MG3S, color-coded and displayed side-by-side.

Table 3.

Properties of HF cyclic clusters at the PMOw and M06-2X/MG3S levels with a combination of experimental and ab initio data that form “best estimates.”

| PMOw | M06-2X/MG3S | “Best estimate”1 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| (HF)3 | |||

| Eint (kcal/mol) | −13.92 | −17.50 | … |

| ⟨rHF⟩ (Å) | 0.935 | 0.934 | 0.933 |

| ⟨rFF⟩ (Å) | 2.66 | 2.60 | 2.59 |

| ⟨θ⟩ (°) | 25.6 | 23.4 | 24 |

| (HF)4 | |||

| Eint (kcal/mol) | −26.56 | −29.73 | … |

| ⟨rHF⟩ (Å) | 0.952 | 0.943 | 0.944 |

| ⟨rFF⟩ (Å) | 2.54 | 2.54 | 2.51 |

| ⟨θ⟩ (°) | 12.8 | 11.2 | 12 |

| (HF)5 | |||

| Eint (kcal/mol) | −36.32 | −40.02 | … |

| ⟨rHF⟩ (Å) | 0.957 | 0.947 | 0.948 |

| ⟨rFF⟩ (Å) | 2.51 | 2.50 | 2.48 |

| ⟨θ⟩ (°) | 5.7 | 5.1 | 6 |

| (HF)6 | |||

| Eint (kcal/mol) | −43.95 | −49.04 | … |

| ⟨rHF⟩ (Å) | 0.957 | 0.949 | 0.949 |

| ⟨rFF⟩ (Å) | 2.51 | 2.49 | 2.47 |

| ⟨θ⟩ (°) | 1.5 | 1.5 | 3 |

| (HF)7 | |||

| Eint (kcal/mol) | −50.44 | −57.23 | … |

| ⟨rHF⟩ (Å) | 0.956 | 0.948 | … |

| ⟨rFF⟩ (Å) | 2.51 | 2.49 | … |

| ⟨θ⟩ (°) | 1.3 | 0.8 | … |

| (HF)8 | |||

| Eint (kcal/mol) | −56.32 | −64.97 | … |

| ⟨rHF⟩ (Å) | 0.954 | 0.946 | … |

| ⟨rFF⟩ (Å) | 2.51 | 2.50 | … |

| ⟨θ⟩ (°) | 3.2 | 2.4 | … |

Reference 73.

Figure 4.

Labeled quantities for the HF trimer corresponding to quantities given in Table 3. Entries in the table for clusters larger than the trimer have analogous quantities to the labels in the figure.

Figure 5.

Cyclic clusters of HF at the PMOw level (top) and the M06-2X/MG3S level (bottom). The various monomer colors indicate their respective cluster, and are as follows: dimer (red), trimer (blue), tetramer (yellow), pentamer (cyan), hexamer (magenta), heptamer (orange), octamer (black). The multicolored monomer at the bottom of each pane indicates the first monomer in each cluster.

XPHF MODEL FOR LIQUID HF

The explicit polarization model for liquid HF (XPHF) follows the same formalism of X-Pol reported previously.30, 32, 33, 34 The X-Pol method has been applied to liquid water,31, 35 liquid HF,29 and a solvated bovine pancreatic trypsin inhibitor protein using the semiempirical AM1 model to represent individual fragments.36

X-Pol is a fragment-based electronic structure method that incorporates electronic polarization by wave function theory for a condensed-phase system. For this reason, X-Pol is regarded as a QM/QM-type method or a QM force field (QMFF) if relevant parameters are optimized to reproduce experimental properties of liquids and solutions.

In earlier studies, aimed at demonstrating the feasibility of the idea of a QMFF for fluid and biomolecular simulations, the semiempirical AM1 Hamiltonian37 and Mulliken charges74 were used to model intermolecular interactions. The XP3P model for water and the XPHF model for hydrogen fluoride in the present study adopt a new approach, where the PMO method is used as the QM model for individual fragments and the dipole-preserving polarization consistent (DPPC) charge method54 is used to represent partial charges in calculating the interfragment potential, providing a more rigorous and accurate framework for QMFF development.

We now provide a brief description of the X-Pol method, noting that it is covered in greater detail in Refs. 30, 32, 33, 34.

Wave function description

The X-Pol method approximates the total wave function of a chemical system Φ as the Hartree product of the wave functions Ψi of N smaller subsystems called fragments:

| (5) |

In the present case, Ψi is considered to be a Slater determinant75 of each HF monomer, which takes the form of Eq. 6,

| (6) |

where ϕk is a molecular orbital formed by a linear combination of m atomic orbitals (LCAO) described by the basis set {χ} (Eq. 7),

| (7) |

The molecular orbitals are subjected to the orthonormalization condition (Eq. 8),

| (8) |

The Hartree-product approximation (Eq. 5) greatly reduces the computational cost of of the quantum calculation from a formally O([Nm]k) scaling to O(N)O(mk), where k depends on the level of quantum theory used. Note that electrostatic interactions between different monomers scale as O[(Nm)2], which may be reduced to O[Nmlog (Nm)] using particle mesh Ewald.76 The caveat of the Hartree-product approximation is the neglect of the exchange and dispersion interactions between fragments. However, it is worth noting that the intrafragment exchange and dispersion are preserved at the level of quantum theory employed in calculating Ψi.

Effective Hamiltonian and energy expression

The Hamiltonian used in X-Pol is defined as the sum of the electronic Hamiltonians of individual fragments plus all interfragment interactions ,

| (9) |

where is defined as the interaction between fragment i and fragment j. Equation 10 gives the expression for ,

| (10) |

where m is the number of electrons in fragment i, A is the number of atoms in fragment i, denotes the core charge of atom α on fragment i, and is the exchange and dispersion interaction between fragments i and j.

The term Vx(Ψj) describes the electrostatic potential at position x due to the jth QM fragment, and is given by Eq. 11,

| (11) |

where B is the number of atoms in fragment j and x = k and x = α denote an interaction at electronic and nuclear positions, respectively, and ρj(r) denotes the electron density of fragment j derived from Ψj.

The total interaction energy of the system is defined by Eq. 12,

| (12) |

where is the optimized wave function associated with the geometry of fragment i in the gas phase.

The energy calculation can be done in a variational way with respect to partial charges obtained from Mulliken population analysis, leading to an analytical expression for its gradient to be used in molecular dynamics simulations.33

X-Pol with PMOw

The XPHF model employs the semiempirical PMOw Hamiltonian with the parameters given in Table 1 to determine the wave functions Ψi for individual fragments. Under the MNDO formalism,57, 77 which is used in PMOw, all one-electron integrals are approximated as two-electron integrals where a charge density is represented by an s-type distribution. In our implementation, these two-electron integrals are computed by a multipole expansion59 and partial charges are calculated by the DPPC population analysis.54 The functional form and methods used in the XPHF model are identical to those employed in the XP3P model, and only differ by parameters and the system of question.

In the present model, exchange and dispersion are empirically described by the Lennard-Jones 12-6 potential (Eq. 13), although explicit density dependence can be incorporated into the Fock matrix in a manner described by York and co-workers,78

| (13) |

Geometric-mean derived combining rules are used such that and for interactions between different atom types, and the Lennard-Jones parameters used in the XPHF model for F and H are εF = 0.145 kcal/mol, εH = 0.05 kcal/mol, σF = 2.97 Å, and σH = 0.80 Å.

SIMULATION OF LIQUID HF WITH XPHF

We performed Monte Carlo simulations under the isothermal-isobaric ensemble (NPT) at temperature and pressure conditions listed in Table 4. Subsequently, molecular dynamics simulations under the isothermal-isochoric ensemble (NVT) at experimental density for the same 11 state points were performed. The 11 state points were chosen to correspond with other simulation studies of liquid HF, for which the most comprehensive comparison of various models with experiment is given by Pártay and co-workers.39

Table 4.

The state 11 points used in our liquid simulations of HF and their corresponding experimental densities.

Simulation setup

All Monte Carlo simulations were performed using the MCSOL program.55 Each simulation box contained 267 rigid HF monomers with a H–F bond length of 0.930 Å. A switching function was used to smooth intermolecular interactions to zero in the region of 8.5–9.5 Å. Each Monte Carlo move was performed by randomly selecting a HF monomer, randomly translating along a randomly chosen axis at a maximum distance of 0.18 Å, and randomly rotating the monomer about a randomly selected axis centered at the fluorine atom a maximum angle of 17°. Volume moves were attempted every 500 steps with a maximum volume change of 150 Å3. All states were initialized with random position and orientation and given at least 108 configurations for equilibration. The averaging of quantities in the Monte Carlo simulations for each state was carried out over at least an additional 107 configurations after equilibration. About 6 × 106 configurations can be executed per day on a 6-core 2.66 GHz Intel Xeon X7542 Westmer processor for a system of this size using the current version of MCSOL.

All molecular dynamics simulations of the same 11 states were carried out using a version of NAMD modified to incorporate the variational X-Pol potential. Each simulation box was modeled under the NVT ensemble at experimental density, and contained 267 rigid HF monomers that were constrained at a H–F bond length of 0.930 Å by RATTLE.79 The Lowe-Andersen thermostat80, 81 was used to control temperature. A switching function between 8.0 Å and 9.0 Å was employed to evaluate Lennard-Jones interactions, and electronic interfragment interactions were truncated at 9.0 Å. Each state was equilibrated for no less than 106 steps from a set of random coordinates. A time step of 2 fs was used for simulations of each state, and trajectories of 1 ns were used for calculating diffusion coefficients.

Energetic properties

Energies per molecule of each of the 11 states are given in Table 5 for XPHF and the PJV-P, JV-P, JV-NP, HF-Kr, and TIPS models along with experimental values obtained from the Visco-Kofke equation.82 XPHF appears to have similar performance compared with other polarizable models both in the non-supercritical states A-G and in the supercritical states H-K. In some cases (states C, D, and G) the XPHF model slightly underestimates the energy per molecule compared to experiment, while the other polarizable models consistently overestimate the energy per molecule of every state.

Table 5.

Energy per molecule of the 11 states in kJ/mol from XPHF compared to several other models and experiment. All values for the other models originate from Table III of Ref. 39, in which uncertainties are also listed.

| State | XPHF | PJV-P | JV-P | JV-NP | HF-Kr | TIPS | Expt. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | −34.32 ± 0.106 | −32.32 | −31.33 | −32.41 | −29.58 | −30.04 | −38.551 2, 5n2 |

| B | −33.89 ± 0.513 | −29.97 | −31.03 | −32.66 | −27.36 | −28.03 | −34.401 2, 5n2 |

| C | −34.01 ± 0.081 | −31.87 | −31.36 | −32.24 | −28.90 | −29.64 | −31.942 |

| D | −32.55 ± 1.103 | −28.53 | −27.68 | −29.18 | −26.00 | −26.77 | −29.012 |

| E | −29.20 ± 0.151 | −27.17 | −26.29 | −28.36 | −24.98 | −25.30 | −30.361 2, 5n2 |

| F | −29.11 ± 0.368 | −27.02 | −26.11 | −28.10 | −24.74 | −24.90 | −28.221 3, 5n3 |

| G | −24.50 ± 0.173 | −22.84 | −22.21 | −14.49 | −11.10 | −20.96 | −23.081 3, 5n3 |

| H | −6.89 ± 0.702 | −6.82 | −5.98 | −10.27 | −7.32 | −8.81 | −19.751 3, 5n3 |

| I | −7.33 ± 0.947 | −7.73 | −7.28 | −11.32 | −7.48 | −9.17 | −19.831 3, 5n3 |

| J | −16.30 ± 0.695 | −16.77 | −14.08 | −16.40 | −12.59 | −16.01 | −23.391 3, 5n3 |

| K | −18.98 ± 0.186 | −18.23 | −17.24 | −19.14 | −15.70 | −17.52 | −27.491 3, 5n3 |

Electronic properties

The average dipole moment of the 11 states with uncertainties for XPHF are given in Table 6 along with results from the polarizable JV-P model28 and static values from JV-NP and TIPS. It is seen from the table that XPHF is in good agreement with the JV-P model despite its reported large uncertainties.

Table 6.

The average dipole moments of the 11 states in Debye for XPHF and JV-P along with the static values from JV-NP and the TIPS models found in Ref. 28.

| State | XPHF | JV-P | JV-NP | TIPS |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | 2.34 ± 0.0011 | … | 1.83 | 2.04 |

| B | 2.34 ± 0.0078 | … | 1.83 | 2.04 |

| C | 2.34 ± 0.0013 | … | 1.83 | 2.04 |

| D | 2.32 ± 0.0015 | … | 1.83 | 2.04 |

| E | 2.27 ± 0.0019 | … | 1.83 | 2.04 |

| F | 2.27 ± 0.0045 | 2.17 ± 0.49 | 1.83 | 2.04 |

| G | 2.21 ± 0.0025 | 2.11 ± 0.42 | 1.83 | 2.04 |

| H | 1.96 ± 0.0105 | 2.02 ± 0.08 | 1.83 | 2.04 |

| I | 1.97 ± 0.0140 | 2.04 ± 0.24 | 1.83 | 2.04 |

| J | 2.09 ± 0.0092 | 2.06 ± 0.32 | 1.83 | 2.04 |

| K | 2.13 ± 0.0024 | 2.07 ± 0.08 | 1.83 | 2.04 |

Average dipole moments from the previous study employing the AM1 model and Mulliken charges were provided for states F and H. The values were 1.99 and 1.79 Debye, respectively, with a bond length of 0.917 Å, and values of 2.03 and 1.79 Debye for a bond length of 0.973 Å. When compared to the average values from XPHF of 2.27 and 1.96 Debye for states F and H, respectively, and the mean values of JV-P of 2.17 and 2.02 Debye, the poor polarizability of the AM1 model is clearly seen.

Figure 6 shows the distribution of dipole moments for each of the 11 states simulated with XPHF. Dipole moments in each state are clearly enhanced beyond the gas-phase dipole of 1.80 Debye, with the least enhancement occurring in the states with the lowest density (states H and I). General trends with respect to pressure and temperature are apparent, such as the positive correlation of the dipole distribution width with respect to increasing pressure, and the negative correlation in the enhancement of the dipole moment beyond the gas phase value with respect to temperature.

Figure 6.

The mole fraction of average dipole moments for each of the 11 states tested with XPHF. In supercritical states H and I, the distribution appears to take a maximum value near the gas-phase dipole moment, while supercritical states J and K show a wider distribution across many values.

Density

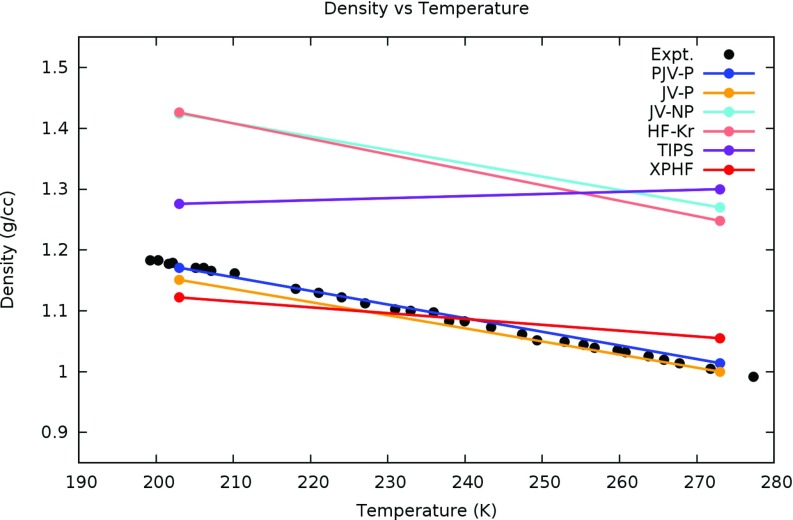

The densities of the 11 states from Monte Carlo simulations are tabulated in Table 7 and compared to the PJV-P, JV-P, JV-NP, HF-Kr, and TIPS models as well as experiment. Uncertainties for all models besides XPHF are given by Pártay and co-workers.39 The XPHF model tends to underestimate the densities for states at higher temperatures when compared to experiment, but appears to be comparable to the polarizable PJV-P and JV-P models in terms of overall trend.

Table 7.

Densities of the 11 states in g/cm3 from XPHF compared to several other models and experiment. Unless otherwise noted, all values for the other models originate from Table IV of Ref. 39, in which uncertainties are also listed.

| State | XPHF | PJV-P | JV-P | JV-NP | HF-Kr | TIPS | Expt. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | 1.112 ± 0.024 | 1.182 | 1.143 | 1.350 | 1.507 | 1.300 | 1.0581 |

| B | 1.081 ± 0.015 | 1.085 | 1.101 | 1.336 | 1.371 | 1.224 | 1.0381 |

| C | 1.122 ± 0.021 | 1.171 | 1.151 | 1.424 | 1.426 | 1.276 | 1.1762 3, 7n3 |

| D | 1.055 ± 0.055 | 1.014 | 1.000 | 1.270 | 1.248 | 1.300 | 1.0152 4, 7n4 |

| E | 0.911 ± 0.030 | 0.950 | 0.923 | 1.234 | 1.190 | 1.019 | 0.9971 |

| F | 0.902 ± 0.041 | 0.951 | 0.924 | 1.230 | 1.171 | 0.9715 | 0.9626 |

| G | 0.748 ± 0.015 | 0.769 | 0.7745 | 0.0195 | 0.029 | 0.6335 | 0.7966 |

| H | 0.068 ± 0.006 | 0.065 | 0.0685 | 0.0735 | 0.068 | 0.0815 | 0.2366 |

| I | 0.078 ± 0.011 | 0.083 | 0.0815 | 0.0975 | 0.070 | 0.0915 | 0.3986 |

| J | 0.392 ± 0.050 | 0.490 | 0.3345 | 0.2945 | 0.240 | 0.4235 | 0.6476 |

| K | 0.636 ± 0.018 | 0.634 | 0.5845 | 0.6155 | 0.511 | 0.5795 | 0.7966 |

A comparison of experimental densities from Sim and Bouknight4 at temperatures ranging from 199.3 K to 277.4 K and atmospheric pressure to state points C (203 K, 1 bar) and D (273 K, 1 bar) of the HF models is shown in Figure 7. It can be seen in the figure that the polarizable models (XPHF, PJV-P, and JV-P) are in better agreement with experiment than the non-polarizable models (JV-NP, HF-Kr, TIPS). The non-polarizable models tend to predict densities much higher than experiment, especially in the case of the TIPS model. However, it is noteworthy that the densities given by Pártay and co-workers for the TIPS model at states C (1.276 ± 0.021 g/cm3) and D (1.300 ± 0.041 g/cm3) are within uncertainty of each other, suggesting that the qualitatively incorrect trend of the TIPS model may be due to convergence issues.

Figure 7.

The temperature dependence of liquid HF density at atmospheric pressure from XPHF and other models at states C and D compared to the experimental values of Simons and Bouknight.4 Notice that the polarizable models (XPHF, PJV-P, JV-P) predict densities in better qualitative and quantitative agreement with experiment than the non-polarizable models (JV-NP, HF-Kr, TIPS).

Although the trend is clearly linear in the temperature dependence of density for the experimental data set shown in Figure 7, the linear interpolation between states C and D of the computational models may be an over-simplification, and more investigation is required to make a definitive conclusion on the linearity of isobaric temperature dependence of density under the various models.

Structural properties

Historically, experimental radial distribution functions (RDFs) for HF have been reported as a total RDF, for which a weighted decomposition of the three pair correlation functions was suggested by Pfleiderer and co-workers7 (Eq. 14),

| (14) |

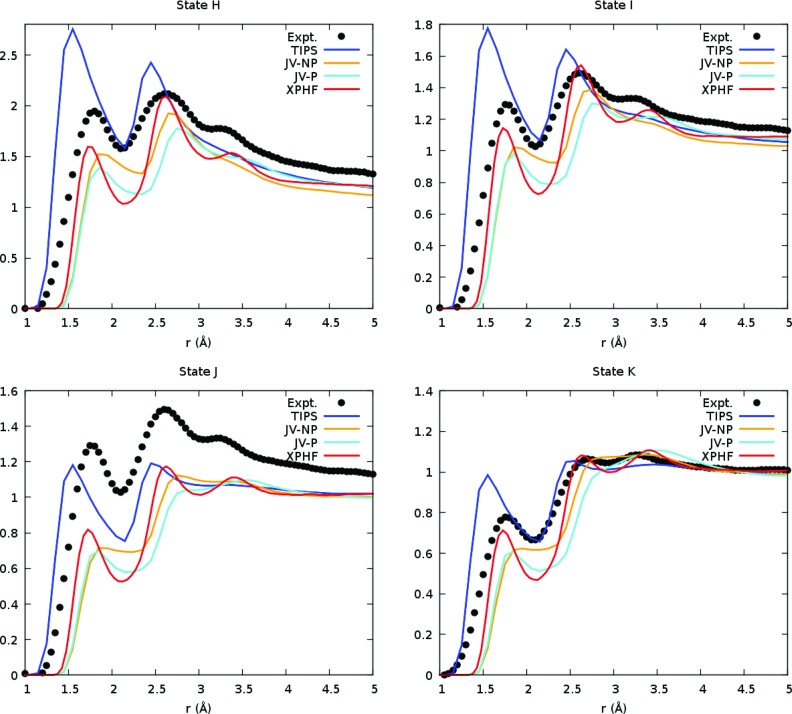

Using these weights, we constructed the total RDFs the supercritical states H-K from NVT molecular dynamics trajectories of XPHF at the experimental densities, and compared them to RDFs of other models and experiment.7 These total RDFs are plotted in Figure 8, showing that XPHF produces slightly better agreement with experiment than the JV-P and JV-NP models for each state. However, it is worth noting that some of the same qualitative differences of those models compared with experiments are observed in XPHF. In particular, state J shows peaks that are much shorter than their values from experiment.

Figure 8.

Total RDFs of the XPHF (red), JV-P (cyan), JV-NP (orange), and TIPS (blue) models with experimental data (black)7 for the four supercritical states at 473 K. The TIPS model is over-structured for all tested supercritical states but J (473 K, 166 bar). XPHF gives results that appear slightly better than the JV-P model, but with more qualitatively-correct peaks.

The partial RDFs of HF (i.e., gFF, gFH, and gHH) were first resolved experimentally in 2004 by McLain and co-workers,8 and reported for a temperature and pressure of 296 K and 1.2 bar (state E). Figure 9 shows a comparison of XPHF and the PJV-P model39 to these partial RDFs and the BOMD result of McGrath and co-workers45 at the BLYP-D2/TZV2P level with temperature and pressure of 300 K and 1.0 bar.

Figure 9.

A comparison of the partial RDFs of HF at state E (296 K, 1.2 bar), for XPHF (red), PJV-P (blue), BOMD at the BLYP-D2/TZV2P level (orange), and the experiment of McLain and co-workers (black).8 XPHF shows agreement with experiment that is comparable to the results of the PJV-P model. Note that the BOMD simulation was performed at a slightly different state of 300 K and 1.0 bar.

Figure 9 shows that the partial RDFs of the XPHF model are in agreement with those of the PJV-P model and they are consistent with experiment. The first peak of the gFF(r) RDF for XPHF appears to be in slightly better agreement with experiment than that of PJV-P in terms of peak position and height. The gFH(r) RDFs behave similarly between the XPHF and PJV-P models in terms of position, with XPHF displaying somewhat higher first and second peaks. Finally, the gHH(r) RDF peak positions are nearly half an Ångstrom too long for both the XPHF and PJV-P models compared to experiment, with the peak heights being higher for XPHF and lower for PJV-P.

The partial RDFs of the BOMD simulation in the NPT ensemble by McGrath and co-workers at a slightly different state point show somewhat better agreement with experiment than the XPHF and PJV-P models at peak positions, particularly in the case of gHH. It has been suggested by Pártay and co-workers that the drop to zero in the experimental gHH RDF is the result of measurement anomaly. This is further supported by the BOMD-derived RDFs, which with that exception have similar first and second peak heights and positions compared to experiment. Although McGrath and co-workers stated that BLYP-D2 was unsatisfactory for accurately describing HF at that state point based upon the calculated density, the partial RDFs are in agreement with experiment and exhibit qualitatively correct behavior for the HH pair correlation function.

Due to the Hartree-product approximation in X-Pol and the use of a two-site model for the HF monomer, the optimized HF dimer in the XPHF model is a linear structure similar to the full MNDO result, but with a better interaction energy profile, as indicated in Figure 2. Although the optimized dimer structure is completely linear, the hydrogen-bonded monomer displays an enhanced charge on the hydrogen atom. Since each monomer must maintain a neutral net charge, the fluorine atom associated with the enhanced charge on the hydrogen atom is also enhanced. This is equivalent to stating that the XPHF model does not incorporate or consider charge transfer effects. On the basis that a bent dimer similar to the full PMOw result, which includes charge transfer effects, has a shorter H-H distance than an analogous linear structure with the same F-F distance, we suggest that the first peak in the gHH RDF could be shortened by the incorporation of charge transfer effects into XPHF.

Diffusion

The self-diffusion coefficients of hydrogen fluoride for the 11 states were determined using the Einstein formula83 on 1 ns trajectories from MD simulations in the NVT ensemble at experimental densities using the momentum conserving and Galilean invariant Lowe-Andersen thermostat.80, 81 Equation 15 gives the Einstein formula,

| (15) |

where r(t) denotes the position of the fluorine atom at time t. Diffusion coefficients were measured using a linear fit of ⟨|r(t) − r(0)|2⟩/6 in the middle region of the curve from the MD trajectories. Diffusion coefficients from XPHF and experiments84 are given in Table 8. Experimental values for states A-H and K were determined from the Arrhenius equation DExpt. = D0exp ( − EA/RT) where EA = 9.92 kJ/mol and the values for D0 are 452 × 109 and 398 × 10−9 m2/s for standard vapor pressure (A-H) and 500 Bar (K), respectively.

Table 8.

Diffusion coefficients in 10−9 m2/s as predicted by XPHF at the 11 state points with comparison to experiment.84 Experimental values for states A-H and K were determined from the Arrhenius equation DExpt. = D0exp ( − EA/RT) where EA = 9.92 kJ/mol and D0 = 452 and D0 = 398 10−9m2/s for standard vapor pressure (A-H) and 500 Bar (K), respectively.

| State | T (K) | ρ (g/cm3) | DXPHF | DExpt. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | 195 | 1.058 | 1.12 | 1.00 |

| B | 246 | 1.038 | 2.92 | 3.54 |

| C | 203 | 1.176 | 1.11 | 1.27 |

| D | 273 | 1.015 | 5.27 | 5.72 |

| E | 296 | 0.997 | 6.85 | 8.03 |

| F | 300 | 0.962 | 6.95 | 8.47 |

| G | 373 | 0.796 | 17.35 | 18.45 |

| H | 473 | 0.236 | 109.01 | 36.28 |

| I | 473 | 0.398 | 71.25 | … |

| J | 473 | 0.647 | 39.70 | … |

| K | 473 | 0.796 | 33.58 | 31.95 |

The computed diffusion coefficients for the non-supercritical states A-G and supercritical state K show good agreement with the Arrhenius equations derived from experiments, while that from state H shows a noticeable discrepancy. In the case of state H, the predicted diffusion coefficient is nearly three times that of experiment, indicating that state H is approaching the vapor phase under XPHF. Although comparable experimental data are unavailable for states I and J, the values likely fall between those from state K and H, suggesting that XPHF has difficulty reproducing the diffusion coefficients in the supercritical states.

Visual inspection of the MD trajectories from states A and C, which had relatively small diffusion coefficients compared to the other states, showed structures of long chains consisting of several HF monomers. This chain-forming behavior is consistent with observations of HF in the solid state by X-ray diffraction,14 for which a freezing point of −83.4 °C has been reported. Since the temperatures of states A and C are near the experimental freezing point temperature, we suggest that the chain-forming behavior could be an indication that the freezing point temperature of XPHF is somewhat near the experimental value.

Deviation in supercritical states

Pártay and co-workers stated that the poor performance of energetic, density, and structural properties of HF in the supercritical states H-K compared to experiments may be due to an overestimation of the pressure at which the maximum value of the isothermal compressibility curve occurs.39 This observation was made by noting that the deviation in these properties compared to experiments is much larger at lower pressures than at higher pressures (see Tables 5, 7). Shortly following that study, Baburao and Visco suggested that the isothermal compressibility of HF in the supercritical region may exhibit more than one maximum,85 further complicating the understanding of HF in the supercritical states.

We estimated the isothermal compressibility κ for the supercritical states H-K by using

| (16) |

where ρ and P denote the density and pressure, respectively, at each state for T = 473 K. Taking a one-sided finite difference for the end points (states H and K) and an average of two one-sided finite differences for the middle points (states I and J), we found κ to be 0.0245, 0.0352, 0.007, and 0.003 bar−1 for states H, I, J, and K, respectively. This behavior of κ is in accord with the other models for HF (see Figure 5 of Ref. 39), suggesting that the accuracy of the XPHF model in the supercritical states may also be affected by this type of overestimation.

CONCLUSION

We have introduced a fluorine parameter into the PMOw model for use with X-Pol as a QMFF for HF – the XPHF model. XPHF shows reasonable agreement with experiments, and is comparable to the JV-P model and its PJV-P re-parameterization in terms of radial distribution functions, energies per molecule, average dipole moments, and density profiles.

Although the results of the XPHF model are comparable to the PJV-P and JV-P models for most quantities tested, several of the same limitations of those models are present in XPHF. Pártay and co-workers suggested that the r−12 term in the Lennard-Jones potential of the PJV-P and JV-P models limits the accuracy of the predicted densities. The XPHF model could be improved by incorporating these exchange and dispersion effects directly into the Fock matrix using an approach similar to that used by York and co-workers.78 Further, a two-body correction to the X-Pol method which incorporates charge transfer effects into individual fragments by examining all interactions of fragment pairs could be used.86 In addition to including charge transfer effects, such an “XP2HF” model could immediately incorporate exchange and dispersion effects through PMO’s pairwise D1 dispersion,61 although such treatment would be empirical. Finally, the semiempirical parameters could be further optimized to give more accurate results, although as in the case of the JV-P and PJV-P models, the improvement would likely not be drastic.

The XPHF model is greatly improved over the previous attempt of modeling HF with X-Pol based on the AM1 model, and our results show that a two-site model for HF can be as accurate as three-site, polarizable models such as PJV-P and JV-P. This further demonstrates the utility of the PMO/X-Pol/DPPC methods for use in force field development beyond the XP3P model for liquid water, suggesting that this approach may be useful as a general framework for a polarizable force field.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Pal Jedlovszky for providing us with the total RDFs of the supercritical states for the TIPS, JV-NP, and JV-P models, and Sylvia McLain for the partial RDFs of the experiment at 296 K and 1.2 bar. We also thank Matthew McGrath and J. Ilja Siepmann for providing us with the BLYP-D2/TZV2P trajectory of 64 HF under the NPT ensemble at 300 K and 1 bar, allowing us to calculate the partial RDFs and make comparisons with that result. This work has been partially supported by National Institutes of Health Grant Nos. GM46376 and RC1-GM091445. Computations were performed on a SGI Altix cluster acquired through National Institutes of Health Grant No. S10-RR029467.

References

- Streng A. G., J. Chem. Eng. Data 16, 357 (1971). 10.1021/je60050a024 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McIntosh R., Kuan T.-S., and Defresart E., J. Electron. Mater. 21, 57 (1992). 10.1007/BF02670920 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sheft I., Perkins A. J., and Hyman H. H., J. Inorg. Nucl. Chem. 35, 3677 (1973). 10.1016/0022-1902(73)80055-7 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Simons J. H. and Bouknight J. W., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 54, 129 (1932). 10.1021/ja01340a015 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Horvath A. L., Z. Phys. Chem. 78, 209 (1972). 10.1524/zpch.1972.78.3_4.209 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Deraman M., Dore J. C., Powles J. G., Holloway J. H., and Chieux P., Mol. Phys. 55, 1351 (1985). 10.1080/00268978500102061 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pfleiderer T., Waldner I., Bertagnolli H., Todheide K., and Fischer H., J. Chem. Phys. 113, 3690 (2000). 10.1063/1.1287427 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McLain S. E., Benmore C. J., Siewenie J. E., Urquidi J., and Turner J. F. C., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 43, 1952 (2004). 10.1002/anie.200353289 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLain S. E., Benmore C. J., Siewenie J. E., Molaison J. J., and Turner J. F. C., J. Chem. Phys. 121, 6448 (2004). 10.1063/1.1790432 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muenter J. S. and Klemperer W., J. Chem. Phys. 52, 6033 (1970). 10.1063/1.1672903 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Huber K. P. and Herzberg G., Molecular Spectra and Molecular Structure (Van Nostrand Reinhold, NY, 1979). [Google Scholar]

- Janzen J. and Bartell L. S., J. Chem. Phys. 50, 3611 (1969). 10.1063/1.1671593 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Howard B. J., Dyke T. R., and Klemperer W., J. Chem. Phys. 81, 5417 (1984). 10.1063/1.447641 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Atoji M. and Lipscomb W. N., Acta Cryst. 7, 173 (1954). 10.1107/S0365110X54000497 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jorgensen W. L. and Cournoyer M. E., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 100, 4942 (1978). 10.1021/ja00484a003 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jorgensen W. L., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 100, 7824 (1978). 10.1021/ja00493a007 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jorgensen W. L., J. Chem. Phys. 70, 5888 (1979). 10.1063/1.437418 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Klein M. L., McDonald I. R., and O’Shea S. F., J. Chem. Phys. 69, 63 (1978). 10.1063/1.436346 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Klein M. and McDonald I., J. Chem. Phys. 71, 298 (1979). 10.1063/1.438071 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hartree D. R., Math. Proc. Camb. Phil. Soc. 24, 89 (1928). 10.1017/S0305004100011919 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fock V., Z. Phys. 61, 126 (1930). 10.1007/BF01340294 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hehre W. J., Stewart R. F., and Pople J. A., J. Chem. Phys. 51, 2657 (1969). 10.1063/1.1672392 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ditchfield R., Hehre W. J., and Pople J. A., J. Chem. Phys. 54, 724 (1971). 10.1063/1.1674902 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yarkony D. R., O’Neil S., Schaefer H. F., Baskin C. P., and Bender C. F., J. Chem. Phys. 60, 855 (1974). 10.1063/1.1681161 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cournoyer M. E. and Jorgensen W. L., Mol. Phys. 51, 119 (1984). 10.1080/00268978400100081 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jedlovszky P. and Vallauri R., Mol. Phys. 92, 331 (1997). 10.1080/002689797170536 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jedlovszky P. and Vallauri R., J. Chem. Phys. 107, 10166 (1997). 10.1063/1.474152 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jedlovszky P., Mezei M., and Vallauri R., J. Chem. Phys. 115, 9883 (2001). 10.1063/1.1413973 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wierzchowski S. J., Kofke D. A., and Gao J., J. Chem. Phys. 119, 7365 (2003). 10.1063/1.1607919 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gao J., J. Phys. Chem. B 101, 657 (1997). 10.1021/jp962833a [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gao J., J. Chem. Phys. 109, 2346 (1998). 10.1063/1.476802 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Xie W. and Gao J., J. Chem. Theory Comput. 3, 1890 (2007). 10.1021/ct700167b [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie W., Song L., Truhlar D. G., and Gao J., J. Chem. Phys. 128, 234108 (2008). 10.1063/1.2936122 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song L., Han J., Lin Y.-L., Xie W., and Gao J., J. Phys. Chem. A 113, 11656 (2009). 10.1021/jp902710a [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han J., Mazack M. J. M., Zhang P., Truhlar D. G., and Gao J., J. Chem. Phys. 139, 054503 (2013). 10.1063/1.4816280 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie W., Orozco M., Truhlar D. G., and Gao J., J. Chem. Theory Comput. 5, 459 (2009). 10.1021/ct800239q [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dewar M. J. S., Zoebisch E. G., Healy E. F., and Stewart J. J. P., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 107, 3902 (1985). 10.1021/ja00299a024 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kreitmeir M., Heusel G., Bertagnolli H., Todheide K., Mundy C. J., and Cuello G. J., J. Chem. Phys. 122, 154511 (2005). 10.1063/1.1877232 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pártay L., Jedlovszky P., and Vallauri R., J. Chem. Phys. 124, 184504 (2006). 10.1063/1.2192771 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Car R. and Parrinello M., Phys. Rev. Lett. 55, 2471 (1985). 10.1103/PhysRevLett.55.2471 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Röthlisberger U. and Parrinello M., J. Chem. Phys. 106, 4658 (1997). 10.1063/1.473988 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kreitmeir M., Bertagnolli H., Mortensen J. J., and Parrinello M., J. Chem. Phys. 118, 3639 (2003). 10.1063/1.1539045 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Izvekov S. and Voth G. A., J. Phys. Chem. B 109, 6573 (2005). 10.1021/jp0456685 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGrath M. J., Ghogomu J. N., Mundy C. J., Kuo I.-F. W., and Siepmann J. I., Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 12, 7678 (2010). 10.1039/b924506e [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGrath M. J., Kuo I.-F. W., and Siepmann J. I., Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 13, 19943 (2011). 10.1039/c1cp21890e [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becke A. D., Phys. Rev. A 38, 3098 (1988). 10.1103/PhysRevA.38.3098 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee C., Yang W., and Parr R. G., Phys. Rev. B 37, 785 (1988). 10.1103/PhysRevB.37.785 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grimme S., J. Comput. Chem. 27, 1787 (2006). 10.1002/jcc.20495 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fritsch S., Potestio R., Donadio D., and Kremer K., J. Chem. Theory Comput. 10, 816 (2014). 10.1021/ct4010504 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morrone J. A. and Car R., Phys. Rev. Lett. 101, 017801 (2008). 10.1103/PhysRevLett.101.017801 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiedler L., Gao J., and Truhlar D. G., J. Chem. Theory Comput. 7, 852 (2011). 10.1021/ct1006373 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang P., Fiedler L., Leverentz H. R., Truhlar D. G., and Gao J., J. Chem. Theory Comput. 7, 857 (2011). 10.1021/ct100638g [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Isegawa M., Fiedler L., Leverentz H., Wang Y., Nachimuthu S., Gao J., and Truhlar D. G., J. Chem. Theory Comput. 9, 33 (2013). 10.1021/ct300509d [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang P., Bao P., and Gao J., J. Comput. Chem. 32, 2127 (2011). 10.1002/jcc.21795 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao J., Han J., Zhang P., and Mazack M. J. M., MCSOL, version 2013xp, Minneapolis, 2013.

- Phillips J. C., Braun R., Wang W., Gumbart J., Tajkhorshid E., Villa E., Chipot C., Skeel R. D., Kalé L., and Schulten K., J. Comput. Chem. 26, 1781 (2005). 10.1002/jcc.20289 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dewar M. J. S. and Thiel W., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 99, 4899 (1977). 10.1021/ja00457a004 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pople J., Beveridge D., and Dobosh P., J. Chem. Phys. 47, 2026 (1967). 10.1063/1.1712233 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dewar M. J. S. and Thiel W., Theor. Chim. Acta 46, 89 (1977). 10.1007/BF00548085 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dewar M. J. S. and Thiel W., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 99, 4907 (1977). 10.1021/ja00457a005 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Grimme S., J. Comput. Chem. 25, 1463 (2004). 10.1002/jcc.20078 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart J. J. P., J. Comput. Aided Mol. Des. 4, 1 (1990). 10.1007/BF00128336 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rocha G. B., Freire R. O., Simas A. M., and Stewart J. J. P., J. Comput. Chem. 27, 1101 (2006). 10.1002/jcc.20425 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart J. J. P., J. Comput. Chem. 10, 209 (1989). 10.1002/jcc.540100208 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart J. J. P., J. Mol. Model. 13, 1173 (2007). 10.1007/s00894-007-0233-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao Y. and Truhlar D. G., Theor. Chem. Acc. 120, 215 (2008). 10.1007/s00214-007-0310-x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fast P. L., Sanchez M. L., and Truhlar D. G., Chem. Phys. Lett. 306, 407 (1999). 10.1016/S0009-2614(99)00493-5 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tratz C., Fast P., and Truhlar D., PhysChemComm 2, 70 (1999). 10.1039/a908207g [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mazack M. J. M. and Gao J., X-Pol, version 2014a1, University of Minnesota, 2014.

- Bylaska E. J., de Jong W. A., Govind N., Kowalski K., Straatsma T. P., Valiev M., Wang D., Apra E., Windus T. L., Hammond J., Nichols P., Hirata S., Hackler M. T., Zhao Y., Fan P.-D., Harrison R. J., Dupuis M., Smith D. M. A., Nieplocha J., Tipparaju V., Krishnan M., Vazquez-Mayagoitia A., Wu Q., Voorhis T. V., Auer A. A., Nooijen M., Crosby L. D., Brown E., Cisneros G., Fann G. I., Fruchtl H., Garza J., Hirao K., Kendall R., Nichols J. A., Tsemekhman K., Wolinski K., Anchell J., Bernholdt D., Borowski P., Clark T., Clerc D., Dachsel H., Deegan M., Dyall K., Elwood D., Glendening E., Gutowski M., Hess A., Jaffe J., Johnson B., Ju J., Kobayashi R., Kutteh R., Lin Z., Littlefield R., Long X., Meng B., Nakajima T., Niu S., Pollack L., Rosing M., Sandrone G., Stave M., Taylor H., Thomas G., van Lenthe J., Wong A., and Zhang Z., NWChem, A Computational Chemistry Package for Parallel Computers, Version 5.1.1 (Pacific Northwest National Laboratory, Richland, Washington, 2009).

- Pine A. S. and Howard B. J., J. Chem. Phys. 84, 590 (1986). 10.1063/1.450605 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tschumper G. S., Yamaguchi Y., and Schaefer H. F., J. Chem. Phys. 106, 9627 (1997). 10.1063/1.473861 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Maerker C., Schleyer P. v. R., Liedl K. R., Ha T.-K., Quack M., and Suhm M. A., J. Comput. Chem. 18, 1695 (1997). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mulliken R. S., J. Chem. Phys. 23, 1833 (1955). 10.1063/1.1740588 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Slater J. C., Phys. Rev. 34, 1293 (1929). 10.1103/PhysRev.34.1293 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang P., Truhlar D. G., and Gao J., Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 14, 7821 (2012). 10.1039/c2cp23758j [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dewar M. J. S. and Yamaguchi Y., Comput. Chem. 2, 25 (1978). 10.1016/0097-8485(78)80005-9 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Giese T. J. and York D. M., J. Chem. Phys. 127, 194101 (2007). 10.1063/1.2778428 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andersen H. C., J. Comput. Phys. 52, 24 (1983). 10.1016/0021-9991(83)90014-1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lowe C. P., Europhys. Lett. 47, 145 (1999). 10.1209/epl/i1999-00365-x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Koopman E. A. and Lowe C. P., J. Chem. Phys. 124, 204103 (2006). 10.1063/1.2198824 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Visco D. P. and Kofke D. A., Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 38, 4125 (1999). 10.1021/ie990356n [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Allen M. P. and Tildesley D. J., Computer Simulations of Liquids (Oxford University Press, Oxford, 1987). [Google Scholar]

- Karger N., Vardag T., and Lüdemann H.-D., J. Chem. Phys. 100, 8271 (1994). 10.1063/1.466771 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Baburao B. and Visco D. P., J. Phys. Chem. B 110, 26204 (2006). 10.1021/jp065491+ [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao J. and Wang Y., J. Chem. Phys. 136, 071101 (2012). 10.1063/1.3688232 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]