Abstract

Purpose

Informal caregivers play a critical role in the care of individuals who are aging or have disabilities, and are at increased risk for poor health outcomes. This study sought to determine if and to what extent: 1) global stress and health-related quality of life (HRQoL) differed between caregivers and non-caregivers; 2) global stress mediated the relationship between caregiving status and HRQoL; and 3) caregiver strain (i.e., stress attributable to caregiving) was associated with worse HRQoL after accounting for global stress.

Methods

Cross-sectional data were from the 2008–2010 Survey of the Health of Wisconsin (SHOW), a representative sample of adults aged 21–74 years. Participants (n=1,364) completed questionnaires about caregiving status, socio-demographics, global stress, and HRQoL. Staged generalized additive models assessed the impact of caregiving on HRQoL and the role of caregiver strain and global stress in this relationship.

Results

17.2% of the sample reported caregiving in the last 12 months. Caregivers reported worse mental HRQoL than non-caregivers (Beta: −1.88, p=0.02); global stress mediated this relationship (p<0.01). Caregivers with the highest levels of strain reported worse mental and physical HRQoL (Beta: −7.12, p<0.01) and caregivers with the lowest levels of strain reported better mental HRQoL (Beta: 2.06, p=0.01) than non-caregivers; these associations were attenuated by global stress (p<0.01).

Conclusion

Global stress, rather than caregiving per se, contributes to poor HRQoL among caregivers, above and beyond the effect of caregiving strain. Screening, monitoring, and reducing stress in multiple life domains presents an opportunity to improve HRQoL outcomes for caregivers.

Keywords: Caregivers, Stress, Psychological, Quality of Life, Population-Based, Survey of the Health of Wisconsin

INTRODUCTION

Informal caregivers (those who provide unpaid care to a family member or friend with an illness or disability) play a critical role in the care of individuals who are aging or have a disability in the U.S. However, informal caregiving puts caregivers at risk for a host of adverse health outcomes [1–4]. With the aging of the U.S. population and increases in the number of individuals with disabilities [5–7], greater numbers of unpaid family members and friends who provide informal care will be at risk of poor health outcomes associated with caregiving. It is therefore vital to understand the pathways by which caregiving may adversely impact health in order to identify caregivers who may be at increased risk, and inform interventions and policies that will protect caregivers and their families.

Health-related quality of life (HRQoL) is an important measure of perceived health status shown to predict future morbidity and mortality [8]. Theory suggests that perceived stress may play a role in the development of poor HRQoL among caregivers [9,10]. In a previous convenience sample, we found that symptoms of stress were critical mediators in the association between caring for a child with cancer and parental HRQoL, suggesting that stress may partially or completely account for differences in HRQoL between caregivers and non-caregivers [11]. However, to our knowledge, no such study has been conducted in a population-based sample. In addition, no previous studies have examined whether global stress accounts for differences in HRQoL between non-caregivers and caregivers reporting different levels of strain. Understanding the role of these two important factors in the development of poor HRQoL will be crucial to identifying high-risk caregivers and areas of intervention to improve the health and well-being of caregivers and their families.

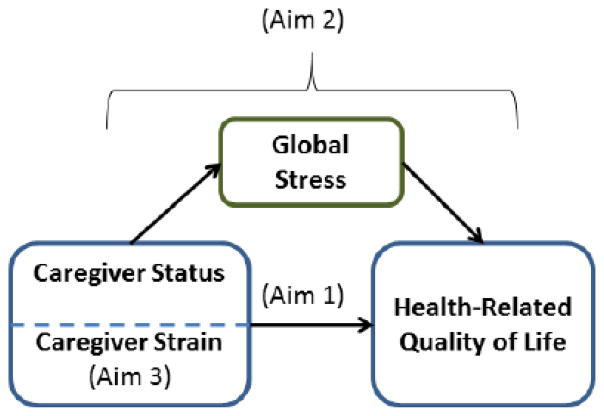

This study therefore sought to determine the relationship between caregiver status and mental and physical HRQoL in a population-based sample of adults ages 21–74 years. Specifically, this study aimed to determine if and to what extent 1) global stress and HRQoL differed between caregivers and non-caregivers; 2) global stress mediated the relationship between caregiving status and HRQoL; and 3) caregiver strain was associated with worse HRQoL, and whether this association remained after accounting for global stress (Figure 1). Findings from this study will provide evidence for the population-level impact of caregiving to inform interventions and policies aimed at improving the HRQoL of informal caregivers and their families.

Figure 1.

Conceptual Model of the Association between Caregiving and Health-Related Quality of Life, by Study Aim. Using data from the Survey of the Health of Wisconsin, 2008–2010 (n=1,364), this study aimed to determine if and to what extent 1) global stress and HRQoL differed between caregivers and non-caregivers; 2) global stress mediated the relationship between caregiving status and HRQoL; and 3) caregiver strain was associated with worse HRQoL, and whether this association remained after accounting for global stress.

METHODS

Data Source

This study used data from the 2008–2010 Survey of the Health of Wisconsin (SHOW). The SHOW is an annual state-wide survey of civilian non-institutionalized adults aged 21–74 years, representative of the state of Wisconsin. A detailed description of SHOW procedures is available elsewhere [12]. Briefly, participants were selected from a random sample of Wisconsin households using a two-stage cluster sampling approach. Participants completed face-to-face interviews, self-administered questionnaires (SAQ), and a physical exam; data collected included detailed demographics, health history, lifestyle and household characteristics, measures of height, weight and blood pressure, perceived stress, and HRQoL. For the present study, all participants who reported their informal caregiving status in the past 12 months were eligible (n=1,364). This study was approved by the Health Sciences Institutional Review Board of the University of Wisconsin-Madison.

Measures

Independent Variables

Identification of Caregivers

Informal caregivers in the SHOW were identified by the question: “There are situations in which people provide regular unpaid care or assistance to a family member (including children) or a friend who has a long-term illness or a disability. In the past 12 months, did you provide any such care or assistance to a family member or friend living with you or living elsewhere?” This question has been used by the National Alliance for Caregiving and the AARP (formerly the American Association of Retired Persons) [13] since 1997 to track caregiving prevalence.

Caregiver Strain

A 12-item version of the Caregiver Strain Index [14] was used to evaluate perceived strain among caregivers and asked respondents whether 12 statements applied to them because of caregiving (e.g., “It is inconvenient for you”); the number of items the respondent endorsed was summed (0–12). To facilitate comparison with non-caregivers, caregivers were then categorized as having low (0–2), middle-low (3–5), middle-high (6–8), or high (9–12) strain based on approximate quartiles of strain, similar to other studies [15]. Cronbach’s alpha in this sample was 0.81.

Dependent Variables

Stress, mental HRQoL and physical HRQoL were examined as dependent variables in this study. The Global Perceived Stress Scale (STS) from the Jackson Heart Study [16] was used to measure global stress over the last 12 months. The STS assesses perceptions of ongoing stressful conditions in eight broad domains: job, relationships, neighborhood, caring for others, legal problems, medical problems, racism/discrimination, and meeting basic needs. Participants rated each domain on a 4-point Likert scale (not stressful [0] to very stressful [3]) and the items were summed to create an overall global stress score. Higher scores indicated greater stress.

The Short Form-12 (SF-12) version 2, a widely used measure of health status, was used to assess the overall mental and physical HRQoL of participants [17]. The SF-12 has eight subscales that were condensed into two summary scales: the physical health component score and the mental health component score, standardized to population norms with a mean of 50 and a standard deviation of 10. The test-retest reliability for the summary scores is 0.89 and 0.76, respectively [17]. Higher scores indicated better HRQoL.

Covariates

Sociodemographic Characteristics

Participants self-reported their age, gender, race/ethnicity (white [non-Hispanic] versus other), annual income, educational attainment, employment status (employed versus unemployed in the past week), type of insurance (none, public, private, or mixed public/private), marital status (married/partnered, divorced/widowed/separated, or never married) and the number of adults and children in the household. Participants reported their combined family income before taxes categorically (e.g., $25,000 to $29,999). These were recoded to the midpoint to approximate a continuous measure; those in the highest income category ($200,000 or more) were recoded to $392,396 by assuming a Pareto distribution of income [18]. Due to the skewed distribution, the natural log of income was used in the final analyses. Educational attainment was reported as the highest grade or level of school completed and recoded as years of education. Caregivers also reported the age and gender of the care recipient, their relationship with the care recipient (spouse, caregiver’s parent, caregiver’s child, or other friend or relative), distance from the recipient (co-resident [living in the same household], 0–20 minutes away, or more than 20 minutes away), and the care recipient’s condition (dementia, recovery from surgery, injury, or acute illness, or other condition).

Lifestyle Factors

Smoking (current, former, or never), alcohol consumption (non-drinker, moderate, or risky drinker), leisure time and transportation-related physical activity (recoded to Metabolic equivalence of task minutes per week [MET-minutes]), diet (fruit/vegetable consumption and percent of calories from fat [19]), were obtained via personal interview. Sleep quality (excellent/very good/good versus fair/poor), sleep problems and sleep duration were self-reported by participants using the SAQ.

Health Factors

Respondents self-reported their history of 47 health conditions (Appendix A: Web Only). The number of health conditions participants endorsed was calculated. An inventory of the medications taken by the participant was conducted during the home interview using a standardized protocol [20], and the total number of prescriptions taken in the past 30 days was calculated. Height and weight were measured during the exam visit, and body mass index (BMI) was calculated.

Analytic Approach

All analyses were conducted in R 2.15.0 [21], due to its flexibility and the availability of packages to conduct the analyses in this study. Multiple imputation with predictive mean matching and a donor-sampling weight of 0.2 was used to predict missing data [22]; five imputations were conducted. Non-linear transformations were allowed when predicting missing values of continuous variables with respect to all other variables in the imputation model. All analyses were conducted using the imputed datasets. Estimates and standard errors were combined using Rubin’s rules [23].

Caregiver and non-caregiver characteristics were compared using cross-tabulations with chi-squared tests and t-tests. Generalized additive models (GAMs) with thin plate regression splines [24] were constructed to determine how caregivers and non-caregivers differed in their stress, mental HRQoL, and physical HRQoL, controlling for sociodemographic covariates (Model 1). Income, education, and age were tested as non-linear terms. Estimated degrees of freedom for non-linear parameters were determined using generalized cross-validation [24]. Next, global stress was added to Model 1 as a non-linear term (Model 2). The relationship between caregiver status and HRQoL was determined to be mediated by global stress if the regression coefficient for caregiver status was attenuated. Mediation was formally tested using Imai’s Causal Mediation Analysis approach [25]. These analyses were repeated with strain as the independent variable.

In order to account for the complex survey design, these models were then run using sampling weights. Non-linear terms were included as natural cubic splines, with fixed degrees of freedom estimated from the GAMs and rounded to the nearest integer. The knots were evenly spaced throughout the distribution of the non-linear terms. The effect size for the regression coefficient for caregiving was calculated by dividing the coefficient by the imputation and survey-weight adjusted standard deviation; effects of 0.2 are loosely considered small, 0.5 moderate, and 0.8 large effects [26].

Sensitivity Analyses

Sensitivity analyses were conducted to determine whether controlling for lifestyle and health factors influenced the results. For analyses including global stress in the past year, sensitivity analyses were conducted dropping those who had been caregivers for less than a year.

RESULTS

Table 1 shows selected characteristics of caregivers and non-caregivers in the sample. Overall, 17.2% of adults were caregivers (unweighted n=264; weighted n=637,199). On average, compared to non-caregivers, caregivers were older and were more likely to be women and unemployed in the past week. Caregivers were more likely to have been divorced, widowed, or separated and less likely to have never been married, and had fewer children in their household. In the unadjusted analyses, caregivers had greater stress (6.5 versus 5.6, p=0.02) and worse physical health (47.6 versus 49.9, p=0.01). Caregivers were also more likely to have smoked, took more prescription medications, and had a greater mean number of health conditions than non-caregivers. Care recipients ranged in age from infancy to 97 years (Table 2). 62% were women, and 15% were spouses of the caregivers, 44% were the caregiver’s parent, and 13% were the caregiver’s child. 33% of care recipients lived with the caregiver. The most prevalent condition or disability was dementia (15%).

Table 1.

Characteristics of caregivers and non-caregivers in the Survey of the Health of Wisconsin, 2008–2010

| Caregivers Unweighted N=264 Weighted N=637,199 (17.2%) Mean (SD) or % |

Non-Caregivers Unweighted N=1,100 Weighted N=3,056,870 (82.8%) Mean (SD) or % |

p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sociodemographics | |||

| Age | 51.7 (12.5) | 44.3 (13.9) | 0.00 |

| Gender | 0.00 | ||

| Women | 65.3% | 46.6% | |

| Men | 34.7% | 53.4% | |

| Race/Ethnicity | 0.64 | ||

| White (non-Hispanic) | 88.6% | 87.1% | |

| Other | 11.4% | 12.9% | |

| Income (in thousands) | 71.2 (80.5) | 71.6 (63.2) | 0.97 |

| Educational Attainment (years) | 14.1 (2.4) | 14.4 (2.2) | 0.21 |

| Employment Status | 0.01 | ||

| Employed | 64.7% | 74.4% | |

| Unemployed | 35.3% | 25.6% | |

| Type of Insurance | 0.05 | ||

| None | 5.8% | 6.8% | |

| Public | 10.7% | 12.0% | |

| Private | 64.8% | 70.9% | |

| Mixed | 18.6% | 10.3% | |

| Marital Status | 0.00 | ||

| Married/Partnered | 73.5% | 72.4% | |

| Divorced/Widowed/Separated | 17.7% | 11.0% | |

| Never Married | 8.8% | 16.6% | |

| Adults in the Household | 2.2 (0.9) | 2.1 (0.8) | 0.10 |

| Children in the Household | 0.7 (1.1) | 0.9 (1.2) | 0.01 |

| Psychosocial Factors | |||

| Global Stressa | 6.5 (4.2) | 5.6 (3.8) | 0.02 |

| Mental HRQoL b | 49.5 (9.4) | 50.9 (8.9) | 0.11 |

| Physical HRQoL b | 47.5 (10.3) | 49.9 (9.4) | 0.01 |

| Lifestyle Factors | |||

| Smoking Status | 0.03 | ||

| Current | 17.6% | 16.5% | |

| Former | 35.3% | 26.8% | |

| Never | 47.0% | 56.3% | |

| Alcohol Consumption Status | 0.87 | ||

| Non-Drinker | 43.5% | 41.1% | |

| Moderate | 42.3% | 44.6% | |

| Risky | 14.2% | 14.3% | |

| Physical Activity | |||

| MET-minutes per week | 1,932.5 (2,868.3) | 2,277.9 (3,787.5) | 0.21 |

| Mins of Housework per Month | 929.4 (1,729.8) | 816.7(1,811.5) | 0.38 |

| Fruit/Vegetable Consumption (servings/day) | 2.6 (1.6) | 2.5 (1.5) | 0.35 |

| Percent Calories from Fat | 34.8% (6.7) | 34.9% (6.7) | 0.82 |

| Sleep Quality (past month) | 0.89 | ||

| Excellent | 5.3% | 5.8% | |

| Very good | 17.7% | 23.1% | |

| Good | 43.4% | 41.0% | |

| Fair | 25.8% | 22.1% | |

| Poor | 7.7% | 8.0% | |

| Number of Sleep Problems | 1.1 (1.4) | 1.0 (1.4) | 0.46 |

| Sleep Time (Hrs/Night) | 6.8 (1.1) | 6.8 (1.1) | 0.94 |

| Health Factors | |||

| Number of Prescriptions | 2.9 (3.5) | 2.0 (3.1) | 0.00 |

| Total Number of Conditions | 4.2 (2.4) | 3.4 (2.3) | 0.00 |

Global Perceived Stress Scale

Short Form-12 version 2

SD: Standard deviation; HRQoL: Health-related quality of life; MET: Metabolic equivalent of task.

Table 2.

Characteristics of care recipients in the Survey of the Health of Wisconsin, 2008–2010

| Mean (SD) or % | Range | |

|---|---|---|

| Age | 61.59 (26.55) | 0–97 |

| Gender | ||

| Men | 38.05% | -- |

| Women | 61.95% | -- |

| Relationship with caregiver | ||

| Spouse | 14.75% | -- |

| Caregiver’s parent | 43.53% | -- |

| Caregiver’s child | 12.94% | -- |

| Other | 28.79% | -- |

| Distance from caregiver | ||

| Co-resident | 32.94% | -- |

| 0–20 minutes | 48.77% | -- |

| More than 20 minutes | 18.30% | -- |

| Condition or disability | ||

| Dementia | 14.62% | -- |

| Recovery from surgery, injury, or acute illness | 7.94% | -- |

| Other | 77.44% | -- |

Care recipient characteristics as reported by caregivers (unweighted n=264; weighted n=637,199) in the Survey of the Health of Wisconsin, 2008–2010

Caregiver Status, and Stress and Mental and Physical HRQoL

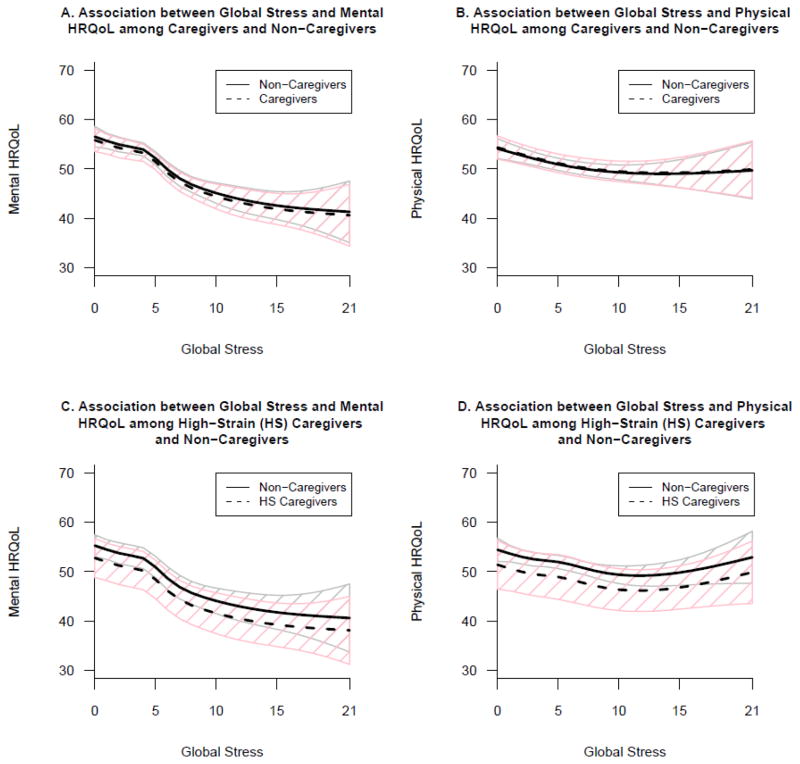

Weighted multivariable analyses revealed that caregivers had significantly greater global perceived stress in the last year than non-caregivers (Beta1: 1.11, p<0.001, Effect Size: 0.28; Table 3). Table 4 presents results of the staged regression models. Caregivers reported worse mental HRQoL than non-caregivers (Beta: −1.88, p=0.02, Effect Size: 0.21). When global stress was added to the model, the effect of caregiving status was more than halved (Beta: −0.68, p=0.37). Greater stress was non-linearly associated with worse mental HRQoL (p<0.0001; Figure 2, Panel A). A formal test revealed that the attenuation was statistically significant, with 46% of the association between caregiver status and mental HRQoL acting via mediation by stress (pmediation<0.01).

Table 3.

Semi-parametric regression of the association between caregiving and global stress in the past yeara, Survey of the Health of Wisconsin, 2008–2010

| Beta | SE | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Linear Terms | |||

| Intercept | 8.08 | 1.18 | |

| Caregiver Status | |||

| Caregiver | 1.11 | 0.33 | 0.00 |

| Non-Caregiver | REFERENCE | ||

| Gender | |||

| Women | 0.20 | 0.21 | 0.34 |

| Men | REFERENCE | ||

| Race/Ethnicity | |||

| White (non-Hispanic) | 0.31 | 0.59 | 0.61 |

| Other | REFERENCE | ||

| Marital/Partner Status | |||

| Married/Partnered | REFERENCE | ||

| Divorced/Widowed/Separated | 0.66 | 0.55 | 0.23 |

| Never Married | −0.90 | 0.47 | 0.06 |

| Employment Status | |||

| Employed | −0.07 | 0.36 | 0.84 |

| Unemployed | REFERENCE | ||

| Household Composition | |||

| No. of Adults | 0.08 | 0.16 | 0.64 |

| No. of Children | 0.09 | 0.14 | 0.54 |

| Education (per 4 Years) | −0.04 | 0.24 | 0.88 |

| Insurance Type | |||

| None | REFERENCE | ||

| Public | −0.64 | 0.73 | 0.38 |

| Private | −2.04 | 0.64 | 0.00 |

| Mixed | −0.50 | 0.95 | 0.59 |

| Doubling of Income | −0.37 | 0.17 | 0.03 |

| Non-Linear Terms | |||

| p-value | |||

| Age | 0.00 | ||

Global Perceived Stress Scale

SE: Standard error.

Table 4.

Staged, weighted semi-parametric regressions of caregiver status and mental and physical HRQoLa, Survey of the Health of Wisconsin, 2008–2010

| Mental HRQoL | Physical HRQoL | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 1 | Model 2 | |||||||||

| Beta | SE | p | Beta | SE | p | Beta | SE | p | Beta | SE | p | |

| Linear Terms | ||||||||||||

| Caregiver Status | ||||||||||||

| Caregiver | −1.88 | 0.78 | 0.02 | −0.68 | 0.76 | 0.37 | −0.16 | 0.83 | 0.85 | 0.21 | 0.83 | 0.80 |

| Non-Caregiver | REFERENCE | REFERENCE | REFERENCE | REFERENCE | ||||||||

| Non-Linear Terms | ||||||||||||

| p | p | p | p | |||||||||

| Global Stress | -- | 0.00 | -- | 0.00 | ||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||

| Linear Terms | ||||||||||||

| Caregiver Status | ||||||||||||

| Non-caregiver | REFERENCE | REFERENCE | REFERENCE | REFERENCE | ||||||||

| Low strainb | 2.06 | 0.83 | 0.01 | 0.83 | 0.78 | 0.29 | 1.05 | 1.26 | 0.41 | 0.68 | 1.23 | 0.58 |

| Middle-low strainb | −2.09 | 1.20 | 0.08 | −1.20 | 1.24 | 0.33 | 0.86 | 1.58 | 0.59 | 1.27 | 1.54 | 0.41 |

| Middle-high strainb | −2.63 | 1.71 | 0.13 | −0.59 | 1.46 | 0.69 | 0.19 | 1.33 | 0.88 | 0.71 | 1.40 | 0.61 |

| High strainb | −7.12 | 1.64 | 0.00 | −2.50 | 1.68 | 0.14 | −4.23 | 1.95 | 0.03 | −3.03 | 2.09 | 0.15 |

| Non-Linear Terms | ||||||||||||

| p | p | p | p | |||||||||

| Global Stressc | -- | 0.00 | -- | 0.00 | ||||||||

Short Form-12 version 2

Caregiver Strain Index

Global Perceived Stress Scale

HRQoL: Health-related quality of life; SE: Standard error.

Model 1: Associations between caregiver status and HRQoL, controlling for age, gender, race/ethnicity, marital status, employment status, household composition, education, insurance type, and income.

Model 2: Global stress was added to Model 1.

Figure 2.

Non-linear associations between global stress in the past year and mental HRQoL (Panel A) and physical HRQoL (Panel B) among caregivers (dashed line) and non-caregivers (solid line) in Wisconsin. Panels C and D depict these associations among caregivers reporting high levels of strain (dashed line) and non-caregivers (solid lines). Panel A, p<0.001; Panel B, p<0.001; Panel C, p<0.001; Panel D, p<0.001. 95% confidence intervals are shaded pink for caregivers/high-strain caregivers and grey for non-caregivers. Global stress was measured using the Global Perceived Stress Scale; Caregiver Strain was measured using the Caregiver Strain Index; HRQoL was measured using the Short Form-12 version 2. HRQoL: Health-related quality of life.

Caregivers overall did not differ from non-caregivers on physical HRQoL (Beta: −0.16, p=0.85). When global stress was added to the model, greater stress was significantly associated with worse physical HRQoL at low levels of stress (p<0.0001; Figure 2, Panel B). This association leveled off at higher levels of stress.

Caregiver Strain and Mental and Physical HRQoL

Caregivers with high levels of strain had worse mental HRQoL than non-caregivers, while those with low levels of strain had better mental HRQoL than non-caregivers (Beta: −7.12, p<0.001, Effect Size: 0.79 and Beta: 2.06, p=0.01, Effect Size: 0.23, respectively; Table 4). Global stress significantly attenuated these relationships such that level of strain was no longer <0.01). Further, greater stress was significantly associated with mental HRQoL (pattenuation associated with worse mental HRQoL (p<0.001; Figure 2, Panel C).

Caregivers reporting high strain had significantly worse physical HRQoL than non-caregivers (Beta: −4.23, p=0.03, Effect Size: 0.44). This effect was significantly attenuated by global stress such that level of strain was no longer significantly associated with physical HRQoL (pattenuation<0.01). Further, greater stress was associated with worse physical HRQoL at low levels of stress (p<0.001; Figure 2, Panel D).

Sensitivity Analyses

Sensitivity analyses revealed that controlling for lifestyle and health factors or limiting the analysis of global stress to those who had been caregivers for at least a year did not substantively influence the results (results not shown).

DISCUSSION

To our knowledge, this is the first population-based study to provide evidence that stress mediates the association between caregiving and HRQoL. Overall, 17% of adults in our sample were informal caregivers, somewhat lower than the national prevalence of caregivers 18 years of age older (28.5%) [13]. Caregivers had worse mental, but not physical, HRQoL than non-caregivers, confirming previous research [2,27–29]. When levels of caregiver strain were examined, caregivers with the highest levels of strain reported worse mental and physical HRQoL. Further, caregivers with the lowest levels of caregiving strain reported better mental HRQoL than non-caregivers, mirroring the finds from Roth et al. [28]. These associations were attenuated after accounting for global stress. These findings highlight the role of global stress, in addition to caregiving-specific strain, in the development of poor HRQoL outcomes among caregivers, and indicate potential points of intervention for practice and policy.

The role of global stress as a mediator in the development of poor caregiver mental HRQoL is particularly important, as this indicates a pathway by which caregiving may influence health. It is not the act of caregiving per se that negatively influences health, but the greater levels of global stress experienced by many caregivers. Importantly, this study clarifies that global stress may be an important factor in the development of poor HRQoL outcomes beyond the effect of caregiver strain, as strain did not exert a stronger influence on HRQoL than global stress. Indeed, follow-up analyses indicated that the attenuation effects in this study were driven by stress related to relationships, caring for others, legal problems, and/or medical problems. Reducing stress in these and other domains of a caregiver’s life may therefore have an important and measurable impact on improving caregivers’ HRQoL and subsequent health outcomes.

This work has several important implications for practice, policy, and research. Clinically, this study reinforces the importance of screening and monitoring stress among caregivers, and emphasizes the need for clinicians to consider both stress that is specific to caregiving, and stress more globally. Expanding integrated care services [30], for example, to address the needs of entire families including caregivers could serve to reduce caregiver stress and strain, improve HRQoL, and protect the health of both caregivers and those for whom they care. Social workers and community specialists, as well as peer support groups, may be important assets for connecting caregivers with resources and assistance that may help reduce their levels of stress both within and outside of their caregiving role. Further, given recent research suggesting that stress perceptions may influence the associations between stress and health [31,32], interventions aiming to encourage re-assessment of stress as beneficial may prove important in improve health outcomes for caregivers and their families.

Policies supporting caregiver services and family-level care are also necessary, including those supporting the ability of clinicians to refer their patient’s caregivers to health, mental health, and community services they may need, and receive reimbursement for such referrals. Although a variety of policies currently exist that aim to support caregivers, the findings from this study indicate that such policies may need to be expanded to support caregivers in other domains of their lives. For example, supporting paid time off or providing Employee Assistance Programs in the workplace, improving health-literacy, or supporting child care services for family caregivers may prove successful in preventing declines in caregiver HRQoL. New, innovative approaches and a paradigm shift that goes beyond the patient to consider adverse health effects on caregivers will be necessary to support caregivers in all life domains.

Finally, additional studies are needed to tease apart the complex relationships between caregiving-specific strain, global stress, and health outcomes. It is likely that caregiver strain and global stress are inter-related, such that an increase in one factor adversely influences the other. Further, stress and strain may act synergistically such that stress in various areas of life may compound the strain experienced due to caregiving. Longitudinal, population-based research will be critical to understanding these relationships and determining the best points of intervention for improving caregiver outcomes. Future research is also necessary to determine whether interventions focusing on global stress, caregiving-specific factors, or a combination of both are most effective at improving caregiver health outcomes.

This study has several potential limitations. First, this was a cross-sectional study and therefore the directionality of the associations cannot be determined. Second, this study classified caregivers as those who had provided care in the past year. As caregivers may drop out of caregiving when they are mentally or physically unable to continue with the role, only the healthiest caregivers may remain in the role. However, this would lead our findings to be conservative estimates of the effect of caregiving. Third, familial and environmental factors that may have influenced the health of both care recipients and their caregivers (e.g., if both individuals smoke(d), or live(d) with smokers) were not accounted for in this study. We also could not account for other factors that may influence HRQoL, such as levels of social support. Finally, this study treated caregivers as a single group; future research needs to assess the association between caregiving characteristics (e.g., relationship to the care recipient) and HRQoL of caregivers in this sample.

This study also has several important strengths. This was the first population-based study to examine the role of stress as a mediator in the relationship between caregiving status and HRQoL. In addition, this was the first study of caregiving to use semi-parametric statistical models to account for the non-linear effects of sociodemographic characteristics on the relationship between caregiving and stress and health outcomes, reducing residual confounding and allowing for better estimation of the effects of caregiving.

CONCLUSIONS

This study examined the HRQoL of caregivers compared to non-caregivers in the state of Wisconsin, and the role of global stress in this relationship. The findings suggest that stress, rather than caregiving per se, contributes to poor HRQoL among caregivers. Therefore, efforts to address stress may provide important intervention points for improving health among a growing number of caregivers nationwide. Importantly, this study also suggests that global stress may be an important factor in the development of poor HRQoL outcomes among caregivers, beyond the effect of caregiving strain or burden alone. Screening, monitoring, and reducing caregiver stress, both specific to the caregiving role and in other life domains, presents an important opportunity to improve HRQoL outcomes for caregivers and their families and offer opportunities for future population-level risk reduction, and health care savings for a number of adverse outcomes.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the Survey of the Health of Wisconsin (SHOW) for the use of their data. Funding for this study was provided by a training grant from the National Institute on Aging (F31 AG 044073, PI: K. Litzelman) and The Center for Demography of Health and Aging (CDHA) at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, which supported the caregiving component of the SHOW interviews (PI: W. P. Witt). Funding for the Survey of the Health of Wisconsin was provided by the Wisconsin Partnership Program (233 PRJ56RV), National Institutes of Health’s Clinical and Translational Science Award (5UL 1RR025011), and National Heart Lung and Blood Institute (1 RC2 HL101468).

Footnotes

Difference in mean global stress between caregivers and non-caregivers; mean global stress in caregivers was 1.11 points higher than non-caregivers, controlling for covariates.

Competing Interests

The authors have no competing interests to report.

References

- 1.Pinquart M, Sorensen S. Correlates of physical health of informal caregivers: a meta-analysis. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2007;62(2):126–137. doi: 10.1093/geronb/62.2.p126. [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pinquart M, Sorensen S. Differences between caregivers and noncaregivers in psychological health and physical health: A meta-analysis. Psychology and Aging. 2003;18(2):250–267. doi: 10.1037/0882-7974.18.2.250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schulz R, O’Brien AT, Bookwala J, Fleissner K. Psychiatric and physical morbidity effects of dementia caregiving: prevalence, correlates, and causes. Gerontologist. 1995;35(6):771–791. doi: 10.1093/geront/35.6.771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schulz R, Beach SR. Caregiving as a risk factor for mortality: the Caregiver Health Effects Study. JAMA. 1999;282(23):2215–2219. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.23.2215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Carter R. Addressing the caregiving crisis. Prev Chronic Dis. 2008;5(1):A02. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.United States Census Bureau. [Accessed 2012];2009 National Population Projections Summary Tables: Constant Net International Migration Scenario. 2009 http://www.census.gov/population/www/projections/2009cnmsSumTabs.html.

- 7.Field MJ, Jette A Committee on Disability in America. The Future of Disability in America. Washington, D.C: The National Academies Press; 2007. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dominick KL, Ahern FM, Gold CH, Heller DA. Relationship of health-related quality of life to health care utilization and mortality among older adults. Aging Clin Exp Res. 2002;14(6):499–508. doi: 10.1007/BF03327351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lazarus RS, Folkman S. Transactional theory and research on emotions and coping. European Journal of personality. 1987;1(3):141–169. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pearlin LI, Mullan JT, Semple SJ, Skaff MM. Caregiving and the Stress Process - an Overview of Concepts and Their Measures. Gerontologist. 1990;30(5):583–594. doi: 10.1093/geront/30.5.583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Witt WP, Litzelman K, Wisk LE, Spear HA, Catrine K, Levin N, et al. Stress-mediated quality of life outcomes in parents of childhood cancer and brain tumor survivors: a case-control study. Qual Life Res. 2010;19(7):995–1005. doi: 10.1007/s11136-010-9666-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nieto FJ, Peppard PE, Engelman CD, McElroy JA, Galvao LW, Friedman EM, et al. The Survey of the Health of Wisconsin (SHOW), a novel infrastructure for population health research: rationale and methods. Bmc Public Health. 2010;10:785. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-10-785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.National Alliance for Caregiving & AARP. Caregiving in the U.S. Washington, DC: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Robinson BC. Validation of a Caregiver Strain Index. J Gerontol. 1983;38(3):344–348. doi: 10.1093/geronj/38.3.344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Buyck JF, Bonnaud S, Boumendil A, Andrieu S, Bonenfant S, Goldberg M, et al. Informal caregiving and self-reported mental and physical health: results from the Gazel Cohort Study. Am J Public Health. 2011;101(10):1971–1979. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2010.300044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jackson Heart Study; J. C. Center, editor Jackson Heart Study Analysis Manual, Version 4. 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ware JE, Jr, Kosinski M, Keller SD. A 12-Item Short-Form Health Survey: construction of scales and preliminary tests of reliability and validity. Medical care. 1996;34(3):220–233. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199603000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Parker RN, Fenwick R. The Pareto Curve and Its Utility for Open-Ended Income Distributions in Survey-Research. Social Forces. 1983;61(3):872–885. doi: 10.2307/2578140. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19. [Accessed January 10, 2013];Block Dietary Data Systems Questionnaires and Screeners. http://nutritionquest.com/assessment/list-of-questionnaires-and-screeners/

- 20.Psaty BM, Lee M, Savage PJ, Rutan GH, German PS, Lyles M. Assessing the use of medications in the elderly: methods and initial experience in the Cardiovascular Health Study. The Cardiovascular Health Study Collaborative Research Group. J Clin Epidemiol. 1992;45(6):683–692. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(92)90143-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Harrell FE, Jr with contributions from many other users. Hmisc: Harrell Miscellaneous. 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rubin DB. Multiple imputation for nonresponse in surveys. Vol. 17. New York: John Wiley & Sons; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wood SN. Generalized additive models: an introduction with R. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Imai K, Keele L, Tingley D. A general approach to causal mediation analysis. Psychol Methods. 2010;15(4):309–334. doi: 10.1037/a0020761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cohen J. Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciencies. Routledge; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ho SC, Chan A, Woo J, Chong P, Sham A. Impact of caregiving on health and quality of life: a comparative population-based study of caregivers for elderly persons and noncaregivers. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2009;64(8):873–879. doi: 10.1093/gerona/glp034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Roth DL, Perkins M, Wadley VG, Temple EM, Haley WE. Family caregiving and emotional strain: associations with quality of life in a large national sample of middle-aged and older adults. Qual Life Res. 2009;18(6):679–688. doi: 10.1007/s11136-009-9482-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Neugaard B, Andresen E, McKune SL, Jamoom EW. Health-Related Quality of Life in a National Sample of Caregivers: Findings from the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System. Journal of Happiness Studies. 2008;9(4):559–575. doi: 10.1007/s10902-008-9089-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Van Raak A, Mur-Veeman I, Hardy B, Steenbergen M, Paulus A. Integrated Care in Europe. Description and Comparison of Integrated Care Delivery and its Context in Six EU Countries. Maarssen: Elsevier; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Keller A, Litzelman K, Wisk LE, Maddox T, Cheng ER, Creswell PD, et al. Does the perception that stress affects health matter? The association with health and mortality. [Research Support, N.I.H., Extramural Research Support, U.S. Gov’t, P.H.S.] Health Psychol. 2012;31(5):677–684. doi: 10.1037/a0026743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nabi H, Kivimaki M, Batty GD, Shipley MJ, Britton A, Brunner EJ, et al. Increased risk of coronary heart disease among individuals reporting adverse impact of stress on their health: the Whitehall II prospective cohort study. Eur Heart J. 2013 doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/eht216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.