Abstract

Cardiac performance decreases with age, which is a major risk factor for cardiovascular disease and mortality in the aging human population, but the molecular mechanisms underlying cardiac aging are still poorly understood. Investigating the role of integrin-linked kinase (ilk) and β1-integrin (myospheroid, mys) in Drosophila, which colocalize near cardiomyocyte contacts and Z-bands, we find that reduced ilk or mys function prevents the typical changes of cardiac aging seen in wildtype, such as arrhythmias. In particular, the characteristic increase in cardiac arrhythmias with age is prevented in ilk and mys heterozygous flies with nearly identical genetic background, and they live longer, in line with previous findings in Caenorhabditis elegans for ilk and in Drosophila for mys. Consistent with these findings, we observed elevated β1-integrin protein levels in old compared with young wild-type flies, and cardiac-specific overexpression of mys in young flies causes aging-like heart dysfunction. Moreover, moderate cardiac-specific knockdown of integrin-linked kinase (ILK)/integrin pathway-associated genes also prevented the decline in cardiac performance with age. In contrast, strong cardiac knockdown of ilk or ILK-associated genes can severely compromise cardiac integrity, including cardiomyocyte adhesion and overall heart function. These data suggest that ilk/mys function is necessary for establishing and maintaining normal heart structure and function, and appropriate fine-tuning of this pathway can retard the age-dependent decline in cardiac performance and extend lifespan. Thus, ILK/integrin-associated signaling emerges as an important and conserved genetic mechanism in longevity, and as a new means to improve age-dependent cardiac performance, in addition to its vital role in maintaining cardiac integrity.

Keywords: Drosophila, Caenorhabditis elegans, arrhythmia, cardiomyopathy, cell adhesion, heart failure, senescence, ilk, myospheroid, parvin, paxillin, pinch, talin

Introduction

With age, heart function declines and the prevalence of heart disease is dramatically increased. For example, the incidence of heart failure and atrial fibrillation is markedly increased in the elderly (Lakatta & Levy, 2003; Roger et al., 2011), which suggests that aging per se is a major risk factor for heart disease. It is well known that the heart undergoes many age-related functional and structural changes (Khan et al., 2002; Bernhard & Laufer, 2008). However, the control mechanisms of cardiac-intrinsic aging, and their coordination with organismal aging, remain elusive.

Cardiac decline with age and many specific age-related changes occurring in the human heart have also been observed in a variety of other species. Therefore, insights from model organisms, such as Drosophila, the simplest (genetic) model system with a heart (Bier & Bodmer, 2004), will likely provide valuable clues for understanding the cellular and molecular mechanisms involved in cardiac aging (Dai et al., 2010; Nishimura et al., 2011). Drosophila has a short lifespan that makes it an ideal model system for studying the genetic underpinnings of aging. Although the linear heart tube of Drosophila is much less complex than the mammalian heart, its development and functional characteristics are remarkably conserved (Bodmer, 1995; Olson, 2006; Ocorr et al., 2007; Cammarato et al., 2008; Bodmer & Frasch, 2010). With age, the fly heart also shows features similar to mammals, including humans, with respect to structural alterations and propensity toward arrhythmias (Wessells et al., 2004; Ocorr et al., 2007; Cammarato et al., 2008; Taghli-Lamallem et al., 2008; Fink et al., 2009). At young ages, surgically exposed fly hearts show a regular myogenic beating pattern. As flies age, these heartbeats become less regular and show increased arrhythmias, which are reminiscent of the increased incidence of atrial fibrillation in elderly humans. Thus, many fundamental aspects of cardiac aging seem to be conserved (Bodmer & Frasch, 2010; Dai et al., 2010), as is organismal aging (Kenyon, 2010).

Integrins are major adhesive transmembrane receptors that bind to the extracellular matrix (ECM). Their activation affects cytoskeletal remodeling and other intracellular signaling pathways (Delon & Brown, 2007). Integrin signaling and the link between integrins and the cytoskeleton are mediated by many proteins, including integrin-linked kinase (ILK), Talin, and focal adhesion kinase (FAK; Geiger et al., 2001). Mammalian ILK is a putative serine/threonine kinase, originally identified as a binding partner for the cytoplasmic tail of β1-integrin (Hannigan et al., 1996,2007). ILK also binds to the adapter proteins Parvin, Pinch, and Paxillin (Pax), thereby providing an integrin signaling platform (Legate et al., 2006). Drosophila has single orthologues of ILK, Parvin, Pinch, and Pax (Legate et al., 2006). In Drosophila, ilk homozygous mutants are embryonic lethal and show severe muscle attachment defects (Zervas et al., 2001). ILK is also essential for development in mouse and Caenorhabditis elegans (MacKinnon et al., 2002; Sakai et al., 2003). Remarkably, RNAi-induced reduction in ILK, or the ILK binding partner Parvin, causes increased longevity in C. elegans (Hansen et al., 2005; Curran & Ruvkun, 2007). These findings suggest that in contrast to complete loss of ilk, which is deleterious for organismal development, moderate ilk knock-down (KD) extends lifespan in C. elegans. Interestingly, heterozygous Drosophila mutants for β1-integrin (mys) also have an increased lifespan (Goddeeris et al., 2003). Therefore, reduced β1-integrin/ILK signaling may also be beneficial for cardiac-specific aging. Interestingly, overexpression of ilk in rat cardiac fibroblasts induces cellular senescence, whereas inhibition of ilk prevents senescence-related changes in these cells (Chen et al., 2006). In contrast, conditionally targeted knockout of ilk in the mouse heart causes left ventricle dilation, heart failure, disaggregation of cardiac tissue, leading to sudden death (White et al., 2006). Taken together, these results indicate a critical role for ilk in establishing and maintaining heart contractility. Thus, we hypothesize that ilk has a dual role in the heart, one that modulates cardiac aging and one that maintains the heart’s structural integrity.

In this study, we demonstrate that reduced integrin/ILK ameliorates the effects of normal cardiac and organismal aging in Drosophila. ilk and mys heterozygotes not only live longer, but their hearts perform better at old age than wild-type controls, similar to young flies. Moreover, moderate cardiac-specific KD of integrin/ILK-associated genes, pax, parvin, talin, and pinch, also prevents the decline of heart performance with age. Conversely, cardiac overexpression of mys causes a senescent-like phenotype in young flies. These findings suggest that the accumulation of β1-integrin at an older age may mediate in part the declining heart function and that a moderate reduction in integrin/ILK activity maintains youthful heart function with age. In contrast, more severe cardiac-specific KD of ilk and other ILK-associated components leads to a higher incidence of cardiac arrhythmia already in young flies, which is accompanied by defective cellular adherence of the cardiomyocytes. Thus, severely compromised integrin/ILK pathway function is detrimental for the heart, but fine-tuned moderate reduction maintains youthful cardiac performance, suggesting a dual role for this complex in regulating cardiac integrity and aging.

Results

ilk heterozygous mutants have extended lifespan in Drosophila

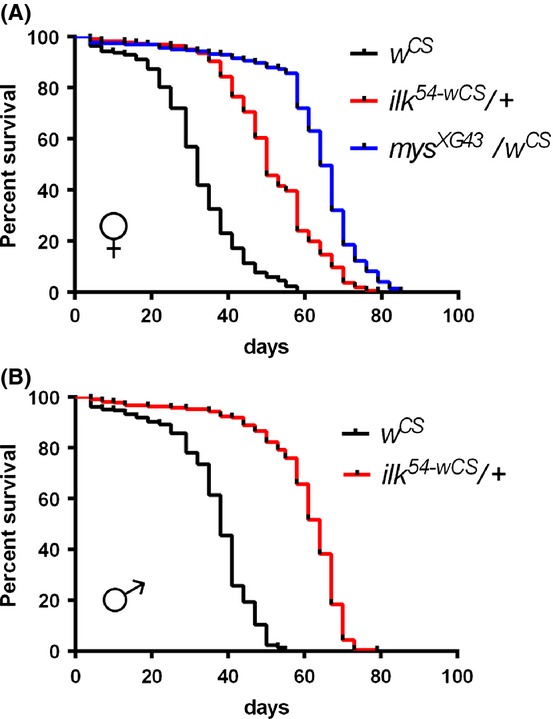

As the RNAi-mediated KD of ilk extends lifespan in C. elegans (Hansen et al., 2005; Curran & Ruvkun, 2007; Kumsta et al., 2014), we wondered whether reduced ilk expression is also beneficial to longevity in Drosophila. As lifespan can be significantly modulated by genetic background (Grandison et al., 2009), we first backcrossed ilk54 mutants (premature stop codon; Zervas et al., 2011; see Experimental procedures) to the wild-type control strain, wCS (Cook-Wiens & Grotewiel, 2002) for six generations. The resulting backcrossed lines are referred to as ilk54-wCS. We found that both female and male ilk54-wCS heterozygous mutants (wCS;ilk54-wCS/+) show extended lifespan compared with their wCS controls (Table 1, Fig. 1).

Table 1.

Lifespan extension in ilk54-wCS/+ and mysXG43/wCS flies

| Sexes | Genotypes | N | Median survival | % extension | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Trial1 | Female | wCS | 153 | 45 | ||

| ilk54-wCS/+ | 110 | 66 | 37 | < 0.0001 | ||

| mysXG43/wCS | 128 | 66 | 44 | < 0.0001 | ||

| Male | wCS | 150 | 45 | |||

| ilk54-wCS/+ | 107 | 66 | 56 | < 0.0001 | ||

| Trial2 | Female | wCS | 222 | 32 | ||

| ilk54-wCS/+ | 217 | 54 | 60 | < 0.0001 | ||

| mysXG43/wCS | 222 | 64 | 95 | < 0.0001 | ||

| Male | wCS | 222 | 38 | |||

| ilk54-wCS/+ | 207 | 64 | 63 | < 0.0001 |

Lifespan was examined in ilk54-wCS/+ and mysXG43/wCS flies first on the smaller scale (Trial 1) and then on larger scale (Trial 2). mys gene is on X chromosome; thus, only female heterozygotes with null mys mutation (mysXG43) can be tested. % extension of mean lifespan compared with wCS is shown. P values were obtained from log-rank analysis (Mantel–Cox test).

Figure 1.

Integrin-linked kinase (ilk) heterozygous mutants have increased lifespan. The lifespan of ilk54-wCS/+ (red), mysXG43/wCS (blue), and wCS (control, black) flies was examined. ilk54 and mysXG43 were introgressed into the wCS wild-type background for six generations. Top, the survival curves of female wCS (mean 32 days, N = 222), ilk54-wCS/+ (mean 51 days, N = 217), and mysXG43/+ (mean 62 days, N = 222) flies. Bottom, the survival curves of male wCS (mean 36 days, N = 222) and ilk54-wCS/+ (mean 59 days, N = 207) flies. As mys is X-linked and hemizygous mys/Y flies are lethal, males could not be examined. Both male and female ilk54-wCS/+ flies, and female myssXG43/+ flies lived longer than the controls (wCS). For statistics, see Table 1. Survival curves of trial 2 in Table 1 are shown.

β1-integrin interacts with ILK (Hanniganet al.,1996,2007), and homozygous mutants (mys) have embryonic muscle phenotypes similar to ilk mutants (Zervas et al., 2001). In addition, mys heterozygotes have previously been reported to exhibit an extended mean lifespan (Goddeeris et al., 2003). Thus, we re-examined the lifespan of mysXG43 heterozygotes (also the wCS genetic background contains small deletion and premature stop codon; Goddeeris et al., 2003; see Experimental procedures) and confirmed that mysXG43/wCS flies have a significantly extended lifespan, similar to ilk54-wCS/+ flies (Table 1, Fig. 1), in terms of both maximum and mean lifespan (Fig. 1). Together, these data suggest a conserved role of the integrin/ILK pathway in organismal aging.

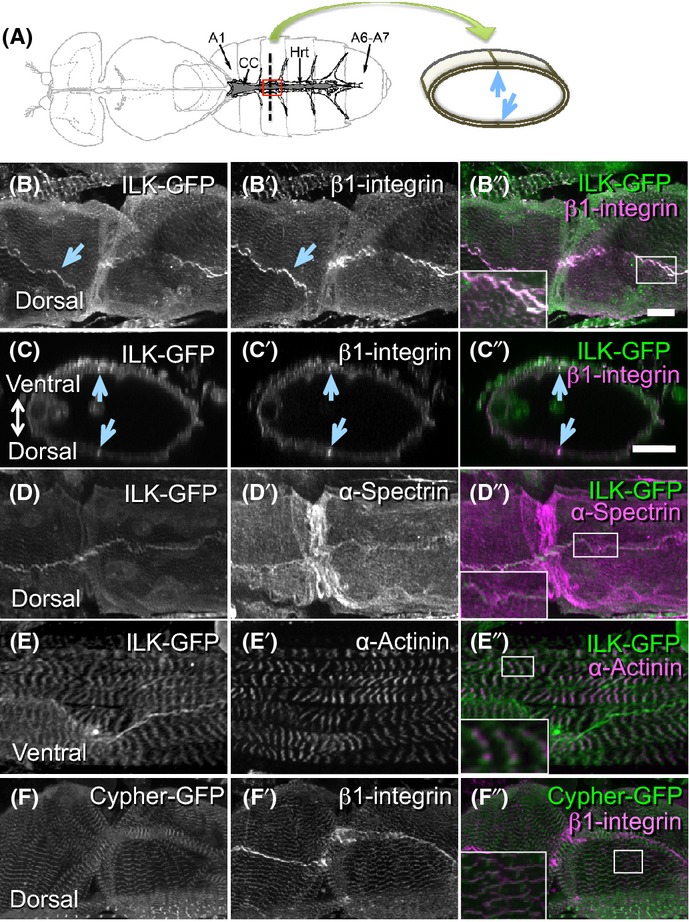

ILK is localized to cell–cell contact sites and Z-disks in adult hearts

To examine ilk expression in the Drosophila heart (Fig. 2A), we used a genomic ilk-GFP fusion rescue construct that contains the putative ilk promoter, enhancers, and ilk transcription unit. This transgene fully rescues the embryonic ilk mutant defects previously reported (Zervas et al., 2001). Similar to the abundant expression of ilk in human hearts (Hanniganet al.,1996,2007), ilk-GFP was also expressed in the adult Drosophila heart and colocalized with β1-integrin (Fig. 2A–C). Interestingly, ILK-GFP and β1-Integrin prominently accumulated at or near cell–cell junctions at both dorsal and ventral sides of cardiomyocytes (Fig. 2B,C, arrows), where it coincides with the cytoskeletal protein α-spectrin (Fig. 2D; Pesacreta et al., 1989). This suggests that ILK and β1-integrin concentrate at the plasma membrane that contacts adjacent cardiomyocytes within the heart tube (see Fig. 2A). ILK-GFP accumulation was also found to colocalize with α-actinin, a sarcomeric Z-disk marker (Fig. 2E). β1-integrin also colocalizes with cypher-GFP, another Z-disk marker in myocardial cells (Fig. 2F).

Figure 2.

Integrin-linked kinase (ILK) and β1-integrin are localized to cell–cell contact sites and Z-disks in fly hearts. (A) Left, a schematic diagram of the adult fly heart (adopted from Cammarato et al., 2008). Hrt, fly heart tube; CC, conical chamber; A1, abdominal segment 1; A6-A7, abdominal segments 6 and 7. The region outlined in red corresponds to the area shown in B, D, E, and F. Right, a schematic diagram of a cross section of the heart tube along the dotted line in the left panel. The circumference of the heart tube is composed of two myocardial cells. Myocardial cell–cell contact sites are pointed out by arrows. (B-B”) Dorsal views of the heart tube. Both ILK (B and green in B”) and β1-integrin (B’ and magenta in B”) are expressed in adult hearts and colocalize. (C-C”) Optical cross sections from B-B” show circumference of the heart tube. The ventral side is to up. Prominent signals of ILK and β1-integrin are indicated by arrows in B–C”. (D-D”) ILK (D and green in D”) was found at the cell membrane labeled with α-spectrin (D’ and magenta in D”). (E-E”) Ventral views of the heart tube. ILK (E and green in E”) was also localized to Z-disks marked by α-actinin (E’ and magenta in E”). (F-F”) Dorsal views of the heart tube. β1-integrin (F and magenta in F”) is also associated with Z-disks marked by cypher-GFP (F’ and green in F”). All the images in B–F” are in abdominal segment 3 region. Insets in B”, D”, E”, and F” are higher magnification images corresponding to the each rectangle in the respective figures. Bars: 20 μm.

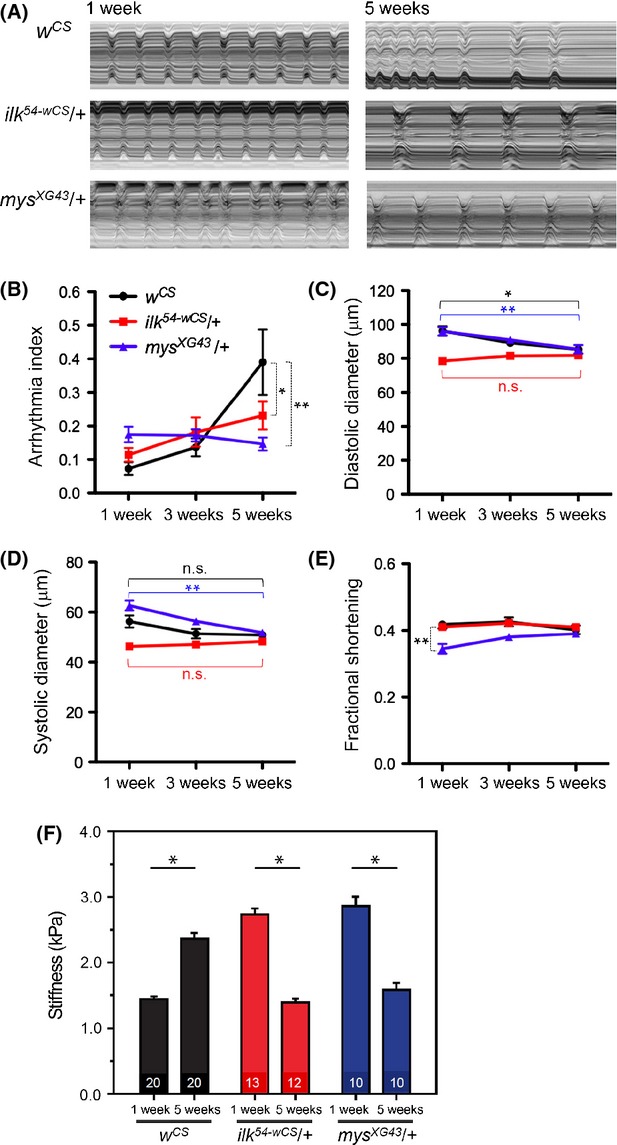

ilk and mys heterozygotes do not exhibit age-related increases in arrhythmias

The expression patterns of ILK and β1-integrin in Drosophila hearts suggest a possible functional requirement for the β1-integrin/ILK pathway in maintaining normal heart structure and function. To test this possibility, we analyzed cardiac performance of ilk and mys heterozygotes using high-speed video imaging of semi-intact heart preparations (Ocorr et al., 2007). At young ages (1 week old), the control hearts show regular beating patterns (see M-modes in Fig. 3A) and consequently a low arrhythmia index (AI; Fig. 3B). Arrhythmia index is the normalized heart period’s standard deviation similar to the coefficient of variation and is a quantification of the variability in heart period (defined as the period from the beginning of one contraction to the beginning of the next contraction; Fink et al., 2009). As wild-type (wCS) flies age, the heart rhythm becomes progressively less regular, as exemplified by increases in AI (Fig. 3A,B; Ocorr et al., 2007). In contrast to wild-type, ilk54-wCS/+ flies exhibit a much diminished increase in AI with age (Fig. 3A,B). To gain additional information about heart function, we also measured systolic and diastolic diameters of the hearts from the video images. Wild-type wCS hearts exhibited a modest decrease in the diastolic as well as systolic diameters with age (Fig. 3C,D), as has previously been observed in other wild-type controls (Cammarato et al., 2008). This suggests a tendency of age-related diastolic dysfunction also in flies, as is the case in humans (Lakatta & Levy, 2003), although this parameter is somewhat variable. In contrast, aging ilk54-wCS/+ flies exhibit no significant difference with age in heart tube diameters; however, hearts from these flies are already relatively constricted even at young ages (Fig. 3C,D). Fractional shortening, a measure of cardiac contractility, was preserved in these flies (Fig. 3E).

Figure 3.

Changes in heart function with age are attenuated in ilk and mys heterozygous mutants. (A) M-mode traces from 10 s movies show heartwall movements in 1-week-old (left) and 5-week-old (right) hearts. Top, wCS. Middle, ilk54-wCS/+. Bottom, mysXG43/+. The incidence of arrhythmia is increased with age in wild-type controls (top panels, see also Ocorr et al., 2007), but 5-week-old ilk54-wCS/+ hearts (middle right) and mysXG43/+ hearts (bottom right) present more regular beating patterns than 5-week-old wCS hearts (top right). (B–E) Plots of physiological parameters of wCS(●), ilk54-wCS/+(■), and mysXG43/+ (▲) at 1, 3, and 5 weeks of age. 20–30 flies were used for each data point. (B) Incidence in heartbeat irregularities indicated by the arrhythmia index (AI) represents the standard deviation of heart period normalized to the median value for each fly (Fink et al., 2009). Arrhythmia index increases with age in wild-type wCS hearts (P < 0.001 for both 3 and 5 weeks), as previously reported for other wild-type strains (Ocorr et al., 2007). Notably, 5-week ilk54-wCS/+ and mysXG43/+ flies had lower AI compared with the age-matched wCS flies. *P < 0.01, **P < 0.001, two-way ANOVA, see Experimental procedures. (C, D) Diastolic diameter decreases with age in wCS, and diastolic and systolic diameters decrease mysXG43/+ flies, but not in ilk54-wCS/+ flies. *P < 0.01, **P < 0.001, two-way ANOVA. (E) Plots of fractional shortening for wCS, ilk54-wCS/+, and mysXG43/+ flies. 1-week-old mysXG43/+ flies had a significantly lower fractional shortening compared to wCS and ilk54-wCS/+. **P < 0.001, two-way ANOVA. (F) Nanoindentation was performed to determine the stiffness (measured in kiloPascal, kPa) of fly heart tubes at the indicated ages and genotypes. Averages and standard errors are shown along with statistical significance, indicated by a Wilcoxon rank-sum test. Number of flies analyzed per condition is indicated at bottom of each bar. *P < 10−7. Error bars indicate SEM.

Similar to ilk54-wCS/+ flies, 5-week-old mysXG43-wCS/+ heterozygotes also exhibited a more regular heart beat pattern, compared with age-matched wCS controls, manifested as a markedly lower AI, thus abolishing the typical wild-type age-related increase in AI (Fig. 3A,B). However, unlike ilk54-wCS/+ flies, old mysXG43-wCS/+ heterozygotes still showed a modest decrease in diastolic diameter, as wCS controls (Fig. 3C); thus, diastolic dysfunction was not prevented in this case. Moreover, young mysXG43-wCS heterozygotes had larger systolic diameters (Fig. 3D) and thus lower fractional shortening (Fig. 3E) compared with controls, suggestive of systolic dysfunction at that age.

We replicated the above findings and confirmed similar trends in different genetic backgrounds: ilk54/+ flies as well as in mysXG43/+ and mys1/+ fly lines that were not backcrossed to the wCS background, but were crossed out to w1118, another laboratory wild-type strain (Fig. S1, Supporting Information). Together, the data suggest that reduction in ilk or mys gene dosage overall attenuates the normally age-dependent changes in heart performance, consistent with an increased lifespan of these flies.

Reduced ilk activity abolishes the age-dependent change in myocardial stiffness

As is observed in human cardiac aging (Lakatta & Levy, 2003), another feature of aging hearts in Drosophila is stiffening of the myocardium (measured in kiloPascals, kPa, upon applying external pressure and at the ventral midline of the heart; Kaushik et al., 2011, 2012). Because ilk heterozygous mutants attenuate or halt the age-dependent changes in heart performance (Fig. 3A,B) and ILK-GFP was found at cell–cell contact sites near the ventral and dorsal midline in the wild-type animal (Fig. 2B–D), we speculated that ILK may be involved in the increase in myocardial stiffness with age. To test this idea, ventral midline stiffness was measured with nanoindentation in ilk54-wCS/+ and corresponding wild-type controls wCS. Aged wCS hearts exhibit a stiffening of approximately 65% with age from 1 to 5 weeks of age (Fig. 3F and Fig. S1B). In contrast to wCS, the ilk54-wCS/+ myocardium did not stiffen with age, but instead started out relatively stiff and then softened with age (Fig. 3F). These results suggest a lack of age-dependent myocardial stiffening in ilk heterozygous mutants. Moreover, mysXG43-wCS/+ myocardium also showed lack of stiffening with age, similar to the ilk54-wCS/+ myocardium (Fig. 3F). Thus, we find that ilk54-wCS/+ and mysXG43-wCS/+ hearts do not display several measures of cardiac aging, such as increasing AI, diastolic dysfunction (except for mysXG43-wCS/+) and myocardial stiffening.

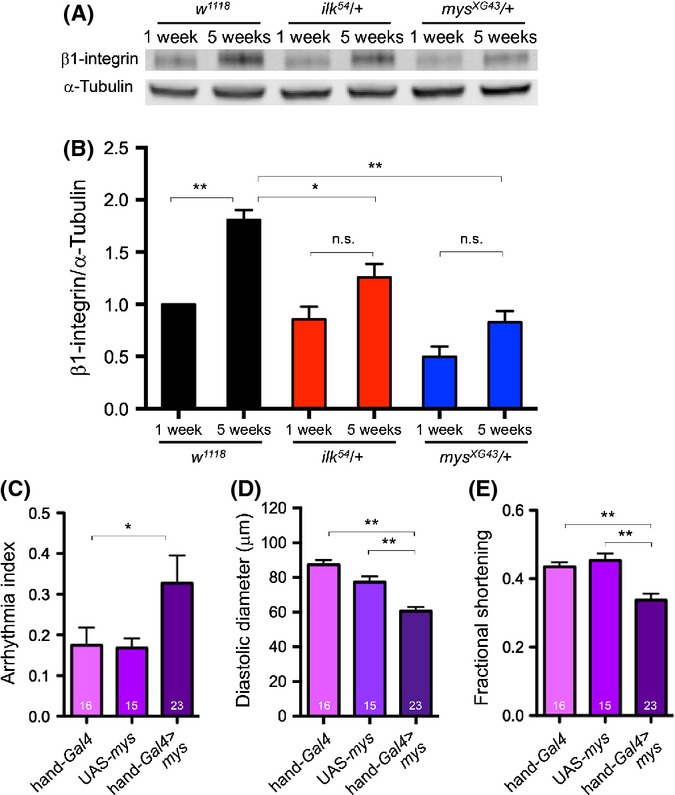

β1-integrin protein levels are increased in old flies and overexpression in young fly hearts mimics the effects of cardiac aging

As ilk and mys heterozygous mutants show a much attenuated progression in several age-dependent characteristics (Fig. 3; Fig. S1), we wondered whether ilk and mys expression levels would be increased in old wild-type flies. Neither mys nor ilk mRNA levels were increased in 5-week- compared with 1-week-old flies (Fig. S2, Supporting Information). However, when examining β1-integrin protein levels, we found an almost two-fold increase at 5 weeks compared with 1 week (Fig. 4A,B). This increase in β1-integrin protein was attenuated in old ilk and mys heterozygotes (Fig. 4A,B). To test whether excess mys function can induce cardiac aging, we overexpressed mys in young hearts and found indeed that it produced an increased AI, reminiscent of old control flies (Fig. 4C). In addition, we observed decreased diastolic diameters and fractional shortening (Fig. 4D,E), suggesting diastolic dysfunction, a characteristic of old flies (Cammarato et al., 2008). Although it is possible that overexpression of mys may cause dominant-negative effects, the observed phenotype did not resemble a mys loss-of-function cardiac phenotype (see also below), but rather the cardiac aging phenotype observed in wild-type flies (Fig. 3B–E). Thus, we suggest that mys overexpression in young hearts may possibly accelerate the cardiac aging phenotype.

Figure 4.

β1-integrin accumulates in old flies and overexpression of mys impairs heart function. (A, B) Western blot analysis was carried out with whole fly preps of 1-week and 5-week-old w1118, ilk54/+, and mysXG43/+ flies, using anti-β1-integrin antibody and anti-α tubulin antibody. β1-integrin was almost twofold higher in 5-week-old wild-type control (w1118) compared with 1 week (**P < 0.001, two-way ANOVA). In contrast, β1-integrin accumulation was suppressed in 5-week-old ilk54/+ and mysXG43/+ flies, compared with 5-week-old w1118 (*P < 0.01, **P < 0.001, two-way ANOVA). (B) Triplicate biological samples were analyzed by western blotting and normalizing to tubulin. All data were normalized to the value for w1118 at 1 week. (C, D, and E) Cardiac overexpression of mys using hand-Gal4 driver significantly increased arrhythmia compared with hand-Gal4 (C), decreased diastolic diameter compared with the controls (hand-Gal4 and UAS-mys) (D), and decreased fractional shortening compared with the controls (hand-Gal4 and UAS-mys) (E) in relatively young flies (3 week old). Sample numbers are indicated at the bottom of each bar. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.001, Kruskal–Wallis test (arrhythmia index) and one-way ANOVA (DD and FS). Error bars are SEM.

Heart-specific ilk knockdown causes arrhythmias and impaired adhesion between cardiomyocytes

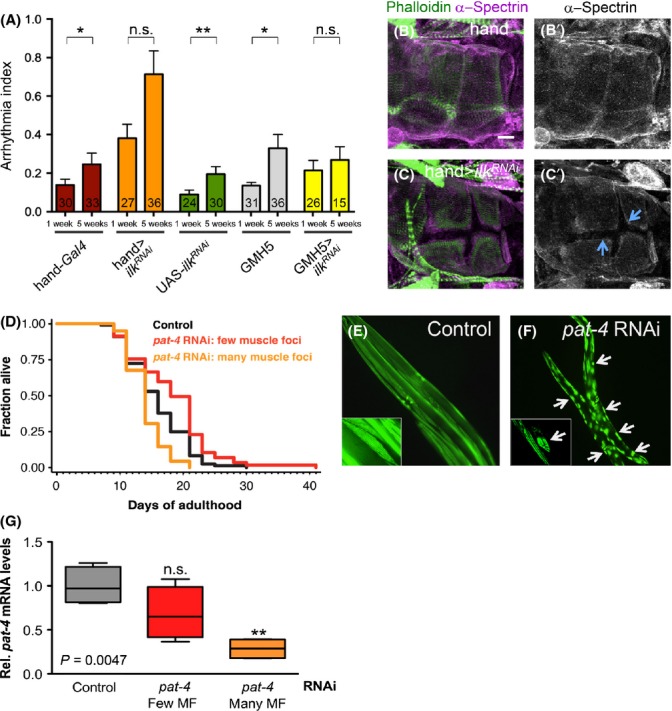

Given the mixed results with ilk manipulations elsewhere (Chen et al., 2006; White et al., 2006), it is possible that ilk has multiple functions. Thus, we hypothesize ilk reduction could have detrimental or beneficial effects depending on the conditions. To ask whether ilk is also critical for maintaining heart function in Drosophila, we examined the effect of cardiac RNAi-mediated knockdown of ilk (using two different drivers, the strong heart-specific hand-Gal4 (that includes some pericardial cells) and the weaker cardiomyocyte-specific GMH5 (Wessells et al., 2004; Han & Olson, 2005). Strong cardiac reduction in ilk leads to high arrhythmias in young flies, which was further elevated at old age (orange bars in Fig. 5A). In contrast, weaker ilk KD in cardiomyocytes (see also qPCR in Fig. S3, Supporting information) prevented an increase in the level of arrhythmias with age (yellow bars in Fig. 5A), unlike in wild-type controls. This suggests that a moderate reduction in ilk, as in ilk heterozygotes (Fig. 3), averts an age-dependent increase in AI, but a more substantial reduction disrupts the regular beating patterns, including at young ages.

Figure 5.

Effect of ilk RNAi knock-down (KD) in Drosophila hearts and of ilk/pat-4 RNAi KD on Caenorhabditis elegans lifespan. (A) Bar graph representations of arrhythmia index (AI) of 1-week- and 5-week-old ilk RNAi hearts. Wild-type controls (hand-Gal4, UAS-ilkRNAi and GMH5) show the expected age-dependent increase in AI. Heart-specific ilk KD hearts (with hand-Gal4, orange bars) have an elevated AI at 1 week, which seemed to worsen with age (not statistically significant). In contrast, cardiomyocyte-specific ilk KD hearts (with GMH5, yellow bars) have a slightly elevated AI at 1 week, which did not exhibit a further increase at 5 weeks. Each sample number is indicated at the bottom of each bar. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, Mann–Whitney test. Error bars are SEM. (B-C’) Heart structure in conical chamber region visualized by phalloidin staining (green in B and C) and anti-α-spectrin antibody (magenta in B and C, grayscale in B’ and C’). Heart-specific ilk RNAi caused gaps between cardiomyocytes (C, C’, arrows). Bar, 20 μm. (D–F) C. elegans expressing a GFP-tagged body-wall muscle myosin reporter (MYO-3::GFP) were fed control bacteria (vector only) or bacteria expressing ilk/pat-4 dsRNA from hatching. (D) On day 1 of adulthood, animals were grouped according to either a low or a high number of detached cytoskeleton in muscle cells (referred to as few or many ‘muscle foci’, respectively, see Experimental procedures), and their lifespan was assayed. While control animals had a mean lifespan of 16 days (N = 104), ilk/pat-4 (RNAi) animals with a low number of detached muscle cells had a mean lifespan of 18 days (N = 114), thus displaying a ~ 15% increase in mean lifespan (P < 0.001, log-rank test). In contrast, ilk/pat-4 (RNAi) animals in which almost all muscle cells were detached displayed a ~ 11% lifespan reduction (mean lifespan 14 days, N = 114, P < 0.005, log-rank test). This experiment was repeated twice with similar results. (E, F) Animals subjected to (E) control RNAi with few ‘muscle’ foci’ or to (F) ilk/pat-4 RNAi with many visible ‘muscle foci’ were imaged on day 2 of adulthood at 50× magnification. Arrows point to examples of muscle cells with detached MYO-3::GFP structures, and inserts show higher magnification of single muscle cells. (G) The ilk/pat-4 transcript levels of animals with a low or a high number of ‘muscle foci’ (MF) were determined using qRT-PCR. Only the animals with a high number of ‘muscle foci’ show a significant reduction in ilk/pat-4 transcript levels (n.s. P > 0.05, **P < 0.005, one-way ANOVA).

To investigate this notion further, we examined the structural integrity of hearts with strong cardiac KD of ilk. With hand-Gal4-mediated KD, we found severe morphological defects in ilk RNAi hearts, including gaps between cardiomyocytes and abnormal patterns of β1-integrin staining, which were not seen in wild-type controls or ilk heterozygous mutants (Fig. 5B–C, Fig. S4A–E, Supporting information). This suggests that ILK may be required for adhesion between cardiomyocytes, consistent with ILK localization at cell–cell contact sites in wild-type hearts (Fig. 2A–C). These results are in contrast to our finding with ilk heterozygous mutants, which showed improved cardiac performance at older age (Fig. 3). Thus, cardiac ilk KD with hand-Gal4 is likely to cause more severe diminution of ilk function than the expected 50% reduction in function of ilk heterozygous mutants or with GMH5-mediated KD (see Fig. S3). Interestingly, heart-specific KD of pinch, encoding an ILK binding partner, results in similar intercellular adhesion defects (Fig. S4F-F”). In addition, heart-specific KD of mys or talin, the latter encoding a critical integrin–actin linker essential for integrin activation, also compromised cardiomyocyte adhesion to their neighbors (Fig. S4G–J). This finding supports the hypothesis that the integrin complex is essential for adhesion between adult cardiomyocytes.

Dual effects of ilk/pat-4 RNAi knockdown on C. elegans longevity

To investigate whether the dual – beneficial versus detrimental – role of scaled reduction in ilk signaling in aging is conserved over a substantial evolutionary distance, we turned to another model aging organism, C. elegans. Similar to ilk or mys null mutations in Drosophila, C. elegans ilk/pat-4 null mutants are also embryonic lethal (MacKinnon et al., 2002). However, post-embryonic RNAi KD results in viable animals with extended lifespan, suggesting ilk/pat-4 as an important and conserved longevity gene (Hansen et al., 2005; Curran & Ruvkun, 2007; Kumsta et al., 2014). However, long-lived animals exposed to pat-4/ILK RNAi since hatching are paralyzed, because of detached cytoskeleton of muscle cells (‘muscle foci’), which was visualized by GFP-tagged myosin heavy chain A/MYO-3 (Fig. 5E,F; Campagnola et al., 2002; Kumsta et al., 2014). This detachment phenotype is reminiscent of what is observed in Drosophila ilk homozygous embryos (Zervas et al., 2001). To test whether the lifespan extension was linked to the paralysis phenotype, we grouped populations of C. elegans with either mild or severe muscle cytoskeleton detachment in early adulthood (Fig. 5E,F) and then carried out lifespan analysis. Interestingly, we found that the population with many MYO-3-positive muscle foci was shorter-lived, whereas the group that had either no or few muscle foci was longer lived (Fig. 5D). To address whether this difference in the lifespan of animals correlated with the severity of the reduction in ilk/pat-4, we conducted qPCR to measure ilk/pat-4 transcript levels in these animals. Indeed, animals with few muscle foci did not exhibit as dramatic a reduction in ilk/pat-4 RNA levels as compared with animals with many muscle foci (Fig. 5G). Taken together, these observations suggest that a substantial reduction in ilk/pat-4 is detrimental for whole organismal physiology and lifespan, whereas a milder reduction improves longevity of C. elegans, thus underlining a dual role in aging and muscle integrity that is evidently conserved in evolution.

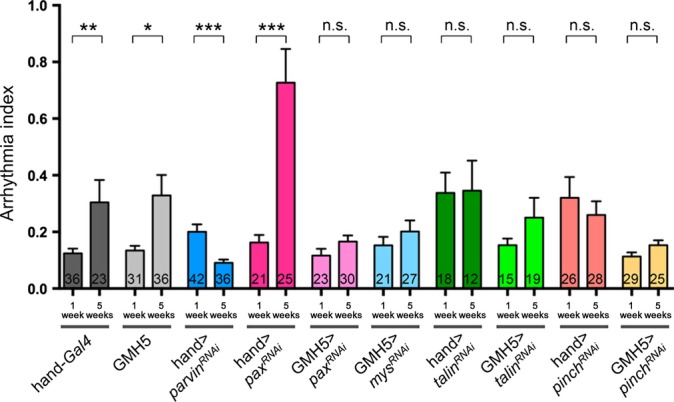

Dual effects of β1-integrin/ILK pathway on heart function

Given the beneficial or detrimental effects depending on the extent of ilk reduction, we wondered whether strong versus weak inhibition of ILK binding partners also could have opposing phenotypic effects on cardiac function in Drosophila. One of ILK’s binding partners is Parvin, an adaptor protein containing two calponin homology domains (Tu et al., 2001). In C. elegans, RNAi KD of parvin (pat-6) significantly extends lifespan, similar to ilk KD (Hansen et al., 2005). Thus, an appropriate reduction in parvin may also have beneficial effects on cardiac aging. When parvin was knocked down in the fly’s heart using hand-Gal4, the flies survived to adulthood and displayed modestly elevated arrhythmias at 1 week of age suggesting a slightly detrimental effect at that age (Fig. 6). However, at 5 weeks of age, the incidence of arrhythmias with parvin KD hearts was low, similar to the 1-week time point of wild-type control (hand-Gal4 alone) and comparable to long-lived ilk and mys heterozygotes (Fig. 3 and Fig. S1) This suggests a beneficial effect of parvin KD on old hearts by preventing an age-dependent increase in AI. Examining pax, talin, and pinch, coding for other ILK-interacting proteins, we found that hand-Gal4-mediated KD exhibited high AI levels for talin and pinch already at young ages (Fig. 6), comparable to strong ilk KD (Fig. 5A), and consistent with the observed structural defects (Fig. S4). In contrast, moderate cardiomyocyte KD (using GMH5) of pax, talin, pinch, as well as mys, exhibited a low AI, typical of 1-week control heart and importantly failed to show any significant age-dependent elevation of AI, unlike their wild-type controls (Fig. 6), thus strongly suggesting a similar beneficial effect of fine-tuned reduction in gene function as with ilk or mys. Interestingly, weak talin KD did not show increased arrhythmias at young ages, but already resulted in some disorganization in myofibrillar structure (Fig. S4I,J).

Figure 6.

RNAi knock-down (KD) analysis of integrin-linked kinase/β1-integrin pathway components. Bar graph representations of the arrhythmia index (AI) of 1- and 5-week-old hearts with hand-Gal4 and GMH5 mediated KD of parvin, pax, mys, talin, and pinch. Wild-type controls (hand-Gal4 and GMH5 drivers alone) show the expected age-dependent increase in AI. In contrast none of the experimental KDs exhibited an age-dependent increase in AI, except for hand > pax-RNAi, which was much elevated at 5 weeks. Moreover, strong hand-driven KD of parvin, talin, and pinch was causing a high AI already at 1 week. Each sample number is indicated at the bottom of each bar. Error bars indicate SEM. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, Mann–Whitney test.

To further substantiate that moderate reduction in ILK pathway components in the myocardium contributes to better cardiac performance at old ages, we examined heterozygous mutants of parvin, pinch (stck), and talin (rhea; see Experimental procedures). All three heterozygotes failed to show an increase in AI or decrease in diastolic diameter at old ages (Fig. S5, Supporting information), thus corroborating the conclusion that they indeed participate in the beneficial modulation of cardiac aging, similar to moderate ilk and mys attenuation (Figs 3 and 5A). Together, these results further support the notion that moderately reduced levels of β1-integrin/ILK signaling components within the heart prevent the increase in cardiac arrhythmias with age, whereas strong reduction causes severe functional and structural defects often already at young ages.

Discussion

Our data demonstrate that the β1-integrin/ILK pathway is a critical genetic modulator of cardiac and organismal aging. We have shown that reduction in β1-integrin/ILK levels is beneficial for Drosophila longevity and cardiac performance at older ages. In addition, severe reduction in ILK pathway components in the heart causes loss of cardiomyocyte cell adhesion, along with structural and functional deficits. We also find that β1-integrin protein levels increase with age in wild-type flies and that overexpression of mys seems to be detrimental to the heart and perhaps causes a premature aging-like phenotype in the heart at young ages. Whether this is a bona fide progeric phenotype awaits further study. However, considering that ilk KD also extends C. elegans lifespan (Hansen et al., 2005; Curran & Ruvkun, 2007; Kumsta et al., 2014), mutation in mys increases Drosophila lifespan (Goddeeris et al., 2003) and that the inhibition of ilk expression prevents senescence in old rat fibroblasts (Chen et al., 2006), we suggest that the role of integrin/ILK pathway components in (cardiac/organismal) aging is likely conserved across species.

Similar to our findings, it has been shown that β1-integrin is significantly higher in old compared with young monkey vascular smooth muscle cells (VSMCs; Qiu et al., 2010). Therefore, the accumulation of β1-integrin might be a common phenomenon underlying both myocardial and vascular aging. Interestingly, applied mechanical force appears to regulate the assembly of focal contacts and integrin turnover (Riveline et al., 2001; Pines et al., 2012), consistent with the idea that with age this regulation is no longer as finely tuned leading to excess integrin accumulation and consequent heart defects.

In contrast to the cardioprotective effects of moderate reductions in integrin/ILK complex levels, more drastic interference with complex function/levels can lead to severe abnormalities in cardiac structure and function, suggesting a critical requirement of this complex across species. In mice, ilk ablation causes dilated cardiomyopathy, heart failure, and sudden death (White et al., 2006). In flies, strong cardiac ilk complex KD causes severe arrhythmia and loss of cardiac integrity, including gaps between adjacent cardiomyocytes. In contrast, the moderate reduction in ilk complex function attenuates the age-dependent changes in cardiac performance, suggesting that alterations in this pathway need to be finely tuned to have beneficial effects, and this seems to be the case across species.

Interestingly, similar observations have been made for ion channel function: Expression of KCNQ, encoding a K+ channel responsible for repolarizing the cardiac action potential, is reduced at old age (Nishimura et al., 2011). Heart-specific overexpression of KCNQ in old wild-type flies reverses the age-dependent increase in arrhythmia, whereas overexpression of KCNQ in young flies increases the incidence of arrhythmias (Ocorr et al., 2007; Nishimura et al., 2011). Thus, precise control of signaling via KCNQ channels, as well as via the integrin/ILK pathway investigated here, seems to be critical for tipping the balance between beneficial and detrimental effects.

Integrins can mediate both ‘outside-in’ and ‘inside-out’ signaling and interactions (Legate et al., 2006). For ‘outside-in’ signaling, integrin activation recruits a large variety of proteins that interface with the actin cytoskeleton and affect many diverse signaling pathways, including ILK-mediated phosphorylation of target genes, such as AKT. However, the requirement for the kinase activity of ILK has been questioned (Wickström et al., 2010), and the longevity effect of ilk/pat-4 RNAi appears to be largely foxo/daf-16 independent in C. elegans (Hansen et al., 2005; Curran & Ruvkun, 2007). Interestingly, the longevity effect of ilk/pat-4 RNAi in C. elegans instead seems to be dependent on heat shock factor HSF-1 (Kumsta et al., 2014). Further investigation is necessary to address whether this is also the case in Drosophila.

With ‘inside-out’ signaling, integrin activation might modulate the assembly of ECM ligands on the cell surface. Excessive deposition of ECM is associated with ventricular fibrosis that leads to stiffening of the ventricular wall causing ventricular dysfunction and heart failure (Pellman et al., 2010). In Drosophila, β1-integrin protein levels are increased with age (Fig. 4A,B) and mys heterozygous mutants lack the age-dependent increase in myocardial stiffness (Fig. 3F). Therefore, it is possible that increased levels of β1-integrin during aging causes excessive ECM deposition leading to stiffening of the heart, which results in diastolic dysfunction and an elevated incidence of arrhythmias with age.

Although in the aggregate our results show that a moderate decrease in several components of β1-integrin/ILK signaling can reverse several characteristics of cardiac aging, it is interesting that there are notable exceptions. For example, mys heterozygotes in the same genetic background as ilk do not reverse the age-dependent decrease in diastolic diameter (Fig. 3C) and thus still show an age-dependent diastolic dysfunction. This may reflect a difference in the functional spectrum of the different signaling components that is not only and completely dedicated to this signaling pathway. Alternatively, an occasional inconstancy may also be due to experimental variability inherent in these types of physiological experiments.

In conclusion, our data provide novel insights into cardiac-specific aging involving a recently identified pathway that modulates organismal aging: the integrin/ILK complex. We find that to maintain a youthful cardiac and organismal physiology, the pathway’s activity needs to be finely tuned and maintained at specific activity levels, and this set point appears to be altered or deregulated during aging. Thus, the integrin/ILK pathway emerges as a key modulator of cardiac homeostasis and aging.

Experimental procedures

Fly strains

ilk54 (Zervas et al., 2011; the allele ilk54 has a premature stop codon instead of a codon for W7), ILK-GFP;ilk54 (ILK-GFP is previously described in Zervas et al., 2001), and UAS-myswt were generous gifts from Y. Inoue. ilk1 (Zervas et al., 2001) and mys1 (Bunch et al., 1992) were obtained from the Drosophila stock center. wCS (Cook-Wiens & Grotewiel, 2002) and mysXG43 (Goddeeris et al., 2003) were kindly provided by M. Grotewiel. The mysXG43 allele is a 113-bp deletion in exon 5 causing a frame shift and premature truncation of mys, and introgressed into the wCS genetic background for six generation (Goddeeris et al., 2003). ilk54 was introgressed into the wCS genetic background for six generation in this study. The following RNAi lines were obtained from Vienna Drosophila RNAi Center (VDRC): UAS-parvinRNAi (#11670), UAS-pinchRNAi (#52538), UAS-mysRNAi (#29619), UAS-talinRNAi (#40399) and UAS-paxillinRNAi (#107789). UAS-ilkRNAi (originally from VDRC, #16062) was kindly given by F. Schnorrer. The effectiveness of ilk, mys, parvin, and talin RNAi lines had been tested in Schnorrer et al. (2010) and found lethal when crossed to the mesodermal driver mef2-Gal4. We have also tested ourselves the pinch and parvin RNAi lines when crossed to mef2-Gal4 and found them lethal as well. In addition, Perkins et al. (2010) tested mys and talin RNAi KD effectiveness. Cardiac-specific driver hand-Gal4 and cardiomyocyte-specific driver GMH5 have been previously described (Wessells et al., 2004; Han & Olson, 2005). parvin694 (Vakaloglou et al., 2012), stckT2 (Zervas et al., 2011), and rhea79A (Brown et al., 2002) were kindly provided by C. Zervas.

Immunostaining

Adult female flies were dissected and immunostained as previously described (Taghli-Lamallem et al. 2008). Images were acquired using ApoTome (Carl Zeiss Microscopy, Thornwood, NY, USA) or FV1000 (Olympus, Center Valley, PA, USA). The following primary antibodies were used: rabbit anti-GFP (1:250, Invitrogen, Grand Island, NY, USA), mouse anti-αPS (1:20, CF.6G11; DSHB Iowa), mouse anti-α-actinin (1:20, kindly provided by J. Saide), and mouse anti-α-spectrin (1:50, 3A9; Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank, University of Iowa, Iowa City, IA, USA).

Lifespan assays

Virgin female and male progeny were collected for 3 days. Then, they were briefly anaesthetized and separated in groups of 25 flies in each vial. The flies were kept at 25 °C, and the dead flies were counted every 3 days after transfer. Each experiment was performed twice: first on the smaller scale (100–150 flies) and then on larger scale (200–250 flies). Data were analyzed using Prism 5.0 (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA, USA).

C. elegans RNAi treatment and lifespan assay

The C. elegans strain RW1596: myo-3 (st386)V; stEx30 [myo-3p::gfp::myo-3 + rol-6] (Campagnola et al., 2002) used in this study was maintained and cultured under standard conditions at 20 °C using Escherichia coli OP50 as a food source, except when subjected to RNAi treatment. The pat-4 RNAi clone was obtained from the Ahringer RNAi library. RNAi treatment was carried out as previously described (Hansen et al., 2005). Muscle detachment was scored on day 1 and day 2 of adulthood under a fluorescent stereoscope, and animals were grouped into two groups based on the efficiency of the RNAi treatment – one group had 0–3 detached muscle cells per animal, whereas the other group had a high degree of detachment (> 80% detached muscle cells per animal). Lifespan assays were carried out as previously described (Hansen et al., 2005). For statistical analysis, Stata software was used (StataCorp, College Station, TX, USA). P values were calculated with the log-rank (Mantel–Cox) method.

Heartbeat analysis

Flies were anesthetized with fly nap (Carolina Biological Supply Co., Burlington, NC, USA) and dissected as previously described (Ocorr et al., 2007). Movies were taken at rates between 140 and 160 frames per second for 30 s using a Hamamatsu CCD digital camera (McBain Instruments, Chatsworth, CA, USA) on a Leica DM LFSA microscope with a 10× water immersion lens and HCImage imaging software. The images were analyzed, and M-modes were generated using Semi-automatic Optical Heart Beat Analysis software (Fink et al., 2009).

Drosophila heart indentation

Adult female flies were anesthetized and immobilized on 25-mm glass coverslips with a thin layer of vacuum grease ventral-side-up. The heart tube was exposed via microsurgery as previously described (Ocorr et al., 2007) with additional micropipette aspiration to remove all ventral tissue proximal to the conical chamber. Each coverslip is mounted on a Fluid Cell Lite coverslip holder (Asylum Research, Goleta, CA, USA) with 1 mL of hemolymph. Hearts are checked for regular contractions to ensure they are in good health and then resubmerged in 10 mm ethylene glycol tetraacetic acid (EGTA)-treated hemolymph to arrest contraction. Prior to indentation, probes were calibrated via thermal noise method in MFP-3D Bio software (Asylum Research). Nanoindentation was performed on an MFP-3D Bio Atomic Force Microscope (Asylum Research) mounted on a Ti-U fluorescent inverted microscope (Nikon Instruments, Melville, NY, USA) with 120 pN nm−1 silicon nitride cantilevers with premounted, 2-μm radius borosilicate glass spheres (Novascan Technologies, Ames, IA, USA). All indentation curves were analyzed to calculate myocardial stiffness using previously published, automated software custom-written in MATLAB (MathWorks, Natick, MA, USA; Kaushik et al., 2011, 2012).

Statistical methods

Statistical Analyses were performed using Prism 6.0 (Graph Pad Software, Inc.). All data were checked prior to analysis using the D’Agostino & Pearson omnibus normality test to determine whether the data violated the assumption of a Gaussian distribution. We employed a one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) when comparing more than two groups (e.g., Fig. 4D,E) followed by Tukey’s multiple comparisons post hoc test. If the data were not normally distributed (e.g., Fig. 4C), a Kruskal–Wallis test was performed followed by Dunn’s multiple comparisons post hoc test. A two-way ANOVA was employed when comparing two or more groups at more than one age (e.g., Fig. 3B–E). Data that did not exhibit a Gaussian distribution (the arrhythmia indices) were first normalized before applying a two-way ANOVA (e.g., Fig. 3B). Post hoc comparisons of two-way ANOVA analyses were made using a Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test. Comparisons of arrhythmia indices within a single genotype between two ages were made using the Mann–Whitney test for nonparametric data (e.g., Fig. 5A). Lifespan analyses were performed using a log-rank analysis (Mantel–Cox test). Specific tests used are indicated in the figure legends. In all cases, P values less than 0.05 were taken as significant.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank all members of the Bodmer Laboratory for helpful discussions, valuable technical supports, and critical comments on the manuscript. We are grateful to Yoshiko Inoue and Nick Brown (The Gurdon Institute, UK), Michael Grotewiel (Michigan State Univ., USA), Frank Schnorrer (Max-Planck Institute, Germany), and Christos G. Zervas (BRFAA, Greece) for providing us with fly strains. We would like to thank Judith Saide (Boston University School of Medicine, USA) and Richard Hynes (MIT, USA) for generous gifts of antibodies.

Funding

This work was supported by grants from the American Heart Association to A.C. and K.O. (Scientist Development Grants), from the Ellison Medical Foundation to M.H. and R.B., and from the National Institutes of Health to M.H. and R.B. (NIA), and to R.S.R., R.B. and A.J.E. (NHLBI).

Conflict of interest

None declared.

Supporting Information

Additional Supporting Information may be found in the online version of this article at the publisher’s web-site.

Fig. S1 ilk heterozygotes and mys heterozygotes retard cardiac decline with age.

Fig. S2 mRNA levels of ilk and mys do not change with age.

Fig. S3 ilk expression is reduced by cardiac RNAi knockdown.

Fig. S4 pinch, mys, and talin RNAi but not ilk heterozygous mutants induce gaps between cardiomyocytes.

Fig. S5 Heterozygous mutants for parvin, pinch and talin lack age-dependent heart function changes.

References

- Bernhard D, Laufer G. The aging cardiomyocyte: a mini-review. Gerontology. 2008;54:24–31. doi: 10.1159/000113503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bier E, Bodmer R. Drosophila, an emerging model for cardiac disease. Gene. 2004;342:1–11. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2004.07.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bodmer R. Heart development in Drosophila and its relationship to vertebrates. Trends Cardiovasc. Med. 1995;5:21–28. doi: 10.1016/1050-1738(94)00032-Q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bodmer R, Frasch M. Development and aging of the drosophila heart. In: Rosethal N, Harvey R, editors. Heart Development and Regeneration. Amsterdam: Elsevier; 2010. pp. 47–86. [Google Scholar]

- Brown NH, Gregory SL, Rickoll WL, Fessler LI, Prout M, White RA, Fristrom JW. Talin is essential for integrin function in Drosophila. Dev. Cell. 2002;3:569–579. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(02)00290-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bunch TA, Salatino R, Engelsgjerd MC, Mukai L, West RF, Brower DL. Characterization of mutant alleles of myospheroid, the gene encoding the subunit of the Drosophila PS integrins. Genetics. 1992;132:519–528. doi: 10.1093/genetics/132.2.519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cammarato A, Dambacher CM, Knowles AF, Kronert WA, Bodmer R, Ocorr K, Bernstein SI. Myosin transducer mutations differentially affect motor function, myofibril structure, and the performance of skeletal and cardiac muscles. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2008;19:553–562. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E07-09-0890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campagnola PJ, Milard AC, Terasak MT, Hoppe PE, Malone CJ, Mohler WA. Three-dimensional higg-resolution second harmonic generation imaging of endogenous structural proteins in biological tissue. Biophys. J. 2002;81:493–508. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(02)75414-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X, Li Z, Feng Z, Wang J, Ouyang C, Liu W, Fu B, Cai G, Wu C, Wei R, Wu D, Hong Q. Integrin-linked kinase induces both senescence-associated alterations and extracellular fibronectin assembly in aging cardiac fibroblasts. J. Gerontol. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 2006;61:1232–1245. doi: 10.1093/gerona/61.12.1232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook-Wiens E, Grotewiel MS. Dissociation between functional senescence and oxidative stress resistance in Drosophila. Exp. Gerontol. 2002;37:1347–1357. doi: 10.1016/s0531-5565(02)00096-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curran SP, Ruvkun G. Lifespan regulation by evolutionarily conserved genes essential for viability. PLoS Genet. 2007;3:e56. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.0030056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dai DF, Wessells RJ, Bodmer R, Rabinovitch PS. Cardiac aging. In: Wolf NS, editor. Comparative Biology of Aging. New York, NY: Springer Science+Business Media; 2010. pp. 259–286. [Google Scholar]

- Delon I, Brown NH. Integrins and the actin cytoskeleton. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 2007;19:43–50. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2006.12.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fink M, Callol-Massot C, Chu A, Ruiz-Lozano P, Izpisua Belmonte JC, Giles W, Bodmer R, Ocorr K. A new method for detection and quantification of heartbeat parameters in Drosophila, zebrafish, and embryonic mouse hearts. Bio Techniques. 2009;46:101–113. doi: 10.2144/000113078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geiger B, Bershadsky A, Pankov R, Yamada KM. Transmembrane crosstalk between the extracellular matrix-cytoskeleton crosstalk. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2001;2:793–805. doi: 10.1038/35099066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goddeeris MM, Cook-Wiens E, Horton WJ, Wolf H, Stoltzfus JR, Borrusch M, Grotewiel MS. Delayed behavioural aging and altered mortality in Drosophila beta integrin mutants. Aging Cell. 2003;2:257–264. doi: 10.1046/j.1474-9728.2003.00060.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grandison RC, Wong R, Bass TM, Partridge L, Piper MD. Effect of a standardised dietary restriction protocol on multiple laboratory strains of Drosophila melanogaster. PLoS ONE. 2009;4:e4067. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0004067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han Z, Olson EN. Hand is a direct target of Tinman and GATA factors during Drosophila cardiogenesis and hematopoiesis. Development. 2005;132:3525–3536. doi: 10.1242/dev.01899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hannigan GE, Leung-Hagesteijn C, Fitz-Gibbon L, Coppolino MG, Radeva G, Filmus J, Bell JC, Dedhar S. Regulation of cell adhesion and anchorage-dependent growth by a new beta 1-integrin-linked protein kinase. Nature. 1996;379:91–96. doi: 10.1038/379091a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hannigan GE, Coles JG, Dedhar S. Integrin-linked kinase at the heart of cardiac contractility, repair, and disease. Circ. Res. 2007;100:1408–1414. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000265233.40455.62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansen M, Hsu AL, Dillin A, Kenyon C. New genes tied to endocrine, metabolic, and dietary regulation of lifespan from a Caenorhabditis elegans genomic RNAi screen. PLoS Genet. 2005;1:119–128. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.0010017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaushik G, Fuhrmann A, Cammarato A, Engler AJ. In situ mechanical analysis of myofibrillar perturbation and aging on soft, bilayered Drosophila myocardium. Biophys. J. 2011;101:2629–2637. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2011.10.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaushik G, Zambon AC, Fuhrmann A, Bernstein SI, Bodmer R, Engler AJ, Cammarato A. Measuring passive myocardial stiffness in Drosophila melanogaster to investigate diastolic dysfunction. J. Cell Mol. Med. 2012;16:1656–1662. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2011.01517.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kenyon CJ. The genetics of ageing. Nature. 2010;464:504–512. doi: 10.1038/nature08980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khan AS, Sane DC, Wannenburg T, Sonntag WE. Growth hormone, insulin-like growth factor-1 and the aging cardiovascular system. Cardiovasc. Res. 2002;54:25–35. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(01)00533-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumsta C, Ching TT, Nishimura M, Davis AE, Gelino S, Catan H, Yu X, Chu CC, Ong B, Panowski SH, Baird N, Bodmer R, Hsu AL, Hansen M. Integrin-linked kinase modulates longevity and thermotolerance in C. elegans through neuronal control of HSF-1. Aging Cell. 2014 doi: 10.1111/acel.12189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lakatta EG, Levy D. Arterial and cardiac aging: major shareholders in cardiovascular disease enterprises: Part II: the aging heart in health: links to heart disease. Circulation. 2003;107:346–354. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000048893.62841.f7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Legate KR, Montañez E, Kudlacek O, Fässler R. ILK, PINCH and parvin: the tIPP of integrin signalling. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2006;7:20–31. doi: 10.1038/nrm1789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon AC, Qadota H, Norman KR, Moerman DG, Williams BD. C. elegans PAT-4/ILK functions as an adaptor protein within integrin adhesion complexes. Curr. Biol. 2002;12:787–797. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(02)00810-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishimura M, Ocorr K, Bodmer R, Cartry J. Drosophila as a model to study cardiac aging. Exp. Gerontol. 2011;46:326–330. doi: 10.1016/j.exger.2010.11.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ocorr K, Reeves NL, Wessells RJ, Fink M, Chen HS, Akasaka T, Yasuda S, Metzger JM, Giles W, Posakony JW, Bodmer R. KCNQ potassium channel mutations cause cardiac arrhythmias in Drosophila that mimic the effects of aging. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2007;104:3943–3948. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0609278104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olson EN. Gene regulatory networks in the evolution and development of the heart. Science. 2006;313:1922–1927. doi: 10.1126/science.1132292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pellman J, Lyon RC, Sheikh F. Extracellular matrix remodeling in atrial fibrosis: mechanisms and implications in atrial fibrillation. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 2010;48:461–467. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2009.09.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perkins AD, Ellis SJ, Asghari P, Shamsian A, Moore ED, Tanentzapf G. Integrin-mediated adhesion maintains sarcomeric integrity. Dev. Biol. 2010;338:15–27. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2009.10.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pesacreta TC, Byers TJ, Dubreuil R, Kiehart DP, Branton D. Drosophila spectrin: the membrane skeleton during embryogenesis. J. Cell Biol. 1989;108:1697–1709. doi: 10.1083/jcb.108.5.1697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pines M, Das R, Ellis SJ, Morin A, Czerniecki S, Yuan L, Klose M, Coombs D, Tanentzapf G. Mechanical force regulates integrin turnover in Drosophila in vivo. Nat. Cell Biol. 2012;14:935–943. doi: 10.1038/ncb2555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qiu H, Zhu Y, Sun Z, Trzeciakowski JP, Gansner M, Depre C, Resuello RR, Natividad FF, Hunter WC, Genin GM, Elson EL, Vatner DE, Meininger GA, Vatner SF. Short communication: vascular smooth muscle cell stiffness as a mechanism for increased aortic stiffness with aging. Circ. Res. 2010;107:615–619. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.110.221846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riveline D, Zamir E, Balaban NQ, Schwarz US, Ishizaki T, Narumiya S, Kam Z, Geiger B, Bershadsky AD. Focal contacts as mechanosensors: externally applied local mechanical force induces growth of focal contacts by an mDia1-dependent and ROCK-independent mechanism. J. Cell Biol. 2001;153:1175–1186. doi: 10.1083/jcb.153.6.1175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roger VL, Go AS, Lloyd-Jones DM, Adams RJ, Berry JD, Brown TM, Carnethon MR, Dai S, de Simone G, Ford ES, Fox CS, Franco S, Fullerton HJ, Gillespie C, Hailpern SM, Heit JA, Howard VJ, Huffman MD, Kissela BM, Kittner SJ, Lackland DT, Lichtman JH, Lisabeth LD, Magid D, Marcus GM, Marelli A, Matchar DB, McGuire DK, Mohler ER, Moy CS, Mussolino ME, Nichol G, Paynter NP, Schreiner PJ, Sorlie PD, Stein J, Turan TN, Virani SS, Wong ND, Woo D, Turner MB. Heart Disease and Stroke Statistics – 2011 Update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2011;123:e18–e209. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0b013e3182009701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakai T, Li S, Docheva D, Grashoff C, Sakai K, Kostka G, Braun A, Pfeifer A, Yurchenco PD, Fässler R. Integrin-linked kinase (ILK) is required for polarizing the epiblast, cell adhesion, and controlling actin accumulation. Genes Dev. 2003;17:926–940. doi: 10.1101/gad.255603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schnorrer F, Schönbauer C, Langer CC, Dietzl G, Novatchkova M, Schernhuber K, Fellner M, Azaryan A, Radolf M, Stark A, Keleman K, Dickson BJ. Systematic genetic analysis of muscle morphogenesis and function in Drosophila. Nature. 2010;464:287–291. doi: 10.1038/nature08799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taghli-Lamallem O, Akasaka T, Hogg G, Nudel U, Yaffe D, Chamberlain JS, Ocorr K, Bodmer R. Dystrophin deficiency in Drosophila reduces lifespan and causes a dilated cardiomyopathy phenotype. Aging Cell. 2008;7:237–249. doi: 10.1111/j.1474-9726.2008.00367.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tu Y, Huang Y, Zhang Y, Hua Y, Wu C. A new focal adhesion protein that interacts with integrin-linked kinase and regulates cell adhesion and spreading. J. Cell Biol. 2001;153:585–598. doi: 10.1083/jcb.153.3.585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vakaloglou KM, Chountala M, Zervas CG. Functional analysis of parvin and different modes of IPP-complex assembly at integrin sites during Drosophila development. J. Cell Sci. 2012;125:3221–3232. doi: 10.1242/jcs.102384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wessells RJ, Fitzgerald E, Cypser JR, Tatar M, Bodmer R. Insulin regulation of heart function in aging fruit flies. Nat. Genet. 2004;36:1275–1281. doi: 10.1038/ng1476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White DE, Coutu P, Shi YF, Tardif JC, Nattel S, St Arnaud R, Dedhar S, Muller WJ. Targeted ablation of ILK from the murine heart results in dilated cardiomyopathy and spontaneous heart failure. Genes Dev. 2006;20:2355–2360. doi: 10.1101/gad.1458906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wickström SA, Lange A, Montanez E, Fässler R. The ILK/PINCH/parvin complex: the kinase is dead, long live the pseudokinase. EMBO J. 2010;29:281–291. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2009.376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zervas CG, Gregory SL, Brown NH. Drosophila integrin-linked kinase is required at sites of integrin adhesion to link the cytoskeleton to the plasma membrane. J. Cell Biol. 2001;152:1007–1018. doi: 10.1083/jcb.152.5.1007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zervas CG, Psarra E, Williams V, Solomon E, Vakaloglou KM, Brown NH. A central multifunctional role of integrin-linked kinase at muscle attachment sites. J. Cell Sci. 2011;124:1316–1327. doi: 10.1242/jcs.081422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Fig. S1 ilk heterozygotes and mys heterozygotes retard cardiac decline with age.

Fig. S2 mRNA levels of ilk and mys do not change with age.

Fig. S3 ilk expression is reduced by cardiac RNAi knockdown.

Fig. S4 pinch, mys, and talin RNAi but not ilk heterozygous mutants induce gaps between cardiomyocytes.

Fig. S5 Heterozygous mutants for parvin, pinch and talin lack age-dependent heart function changes.