Abstract

To develop a systematic review to evaluate, through the best scientific evidence available, the effectiveness of aerobic exercise in improving the biomechanical characteristics of tendons in experimental animals. Two independent assessors conducted a systematic search in the databases Medline/PUBMED and Lilacs/BIREME, using the following descriptors of Mesh in animal models. The ultimate load of traction and the elastic modulus tendon were used as primary outcomes and transverse section area, ultimate stress and tendon strain as secondary outcomes. The assessment of risk of bias in the studies was carried out using the following methodological components: light/dark cycle, temperature, nutrition, housing, research undertaken in conjunction with an ethics committee, randomization, adaptation of the animals to the training and preparation for the mechanical test. Eight studies, comprising 384 animals, were selected; it was not possible to combine them into one meta-analysis due to the heterogeneity of the samples. There was a trend to increasing ultimate load without changes in the other outcomes studied. Only one study met more than 80% of the quality criteria. Physical training performed in a structured way with imposition of overloads seems to be able to promote changes in tendon structure of experimental models by increasing the ultimate load supported. However, the results of the influence of exercise on the elastic modulus parameters, strain, transverse section area and ultimate stress, remain controversial and inconclusive. Such a conclusion must be evaluated with reservation as there was low methodological control in the studies included in this review.

Keywords: aerobic exercise, biomechanics, animals, systematic reviews

INTRODUCTION

The tendon is a connective tissue responsible for the transmission of force from the muscular tissue to the bones, promoting body movement. Its hierarchical structure composed of collagen fibrils, organized into fascicles, makes it a living structure and subject to adjustments and modifications when subjected to overloads [33] imposed on the body, in a planned, structured and repetitive way, in order to maintain or promote improvements in the body, as observed during physical exercise [7].

The study of the practice of physical exercise on tendon structure has shown improvement in vascularization post-physical exercise [10], increased production of interleukin-6 near the peritendinous structure [18], increased collagen synthesis [19], and in addition to structural adaptations [6].

To evaluate these structural adaptations, animal models are used in order to analyse the tendon through biomechanical tests to the point of rupture of the tendon through conventional mechanical test machines [1]. However, the large variety of these machines and the different outcomes of the tendons subjected to an overload of exercise make the real contribution of this therapeutic modality uncertain.

Therefore, this review aims to evaluate, through the scientific evidence available, the effectiveness of aerobic physical exercise in improving the biomechanical characteristics of the tendon in animal models.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This systematic review was carried out by means of a search in the databases of MEDLINE/PUBMED and Lilacs/BIREME, without restriction of year or language. Through the Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) the following descriptors were extracted for selecting articles: “motor activity”, “exercise, running”, “swimming”, “mechanical phenomenal”, “mechanical stress”, “biomechanics”, “tendons” and “connective tissue”. In addition, the following keywords were used: “Mechanical Test”, “Mechanical Properties”, “Mechanical Trial”, “Physical Training”, “Training”, “Physical Activity” and “Treadmill Running”. Moreover, a limitation was established to only include articles that used experimental animals in the study.

The search was conducted in the electronic databases by two independent researchers (MAB and PVCS) using a computer and a pre-defined protocol. A third evaluator (KDSL) was consulted when necessary as an arbitrator for defining inclusion or non-inclusion of articles contested between the researchers. Finally, data extractions were performed in accordance with the evaluation criteria of the eligible studies.

For inclusion in this review, the studies had to 1) present intervention research that assessed the tendon response of experimental animals of any species submitted to aerobic physical exercise, of any kind, by means of 2) the conventional mechanical test to the point of failure of the tendon and 3) compare the group that had trained with a control group without training. Studies were excluded where animals were subjected to surgical interventions to repair the tendon, replacement of the anatomical part or structural sutures, the use of any substances which could enhance or impair the biomechanics of the tendon (e.g., hormones, medicines and anabolic agents), in addition to mechanical tests that used any form of in vivo biomechanical assessment of the tendon.

The assessment of risk of bias of the studies was carried out by individual components of the specific points which interfered in the internal validity of experimental studies, in accordance with the recommendation of Hoojimans et al. [15]. In this way, the following items were assessed: laboratory control over temperature, light/dark cycle, nutrition and housing, randomization of the groups and the evaluation of the study by an ethics committee.

With regard to the quality of the exercise protocol used in different studies, the following aspects were analysed: animal adaptation to the training and preparation of the tendon for the mechanical test.

The following were considered as primary outcomes: ultimate load and elastic modulus; as secondary outcomes: the transverse sectional area of the tendon, tendon strain, and the ultimate stress reached by the tendon.

RESULTS

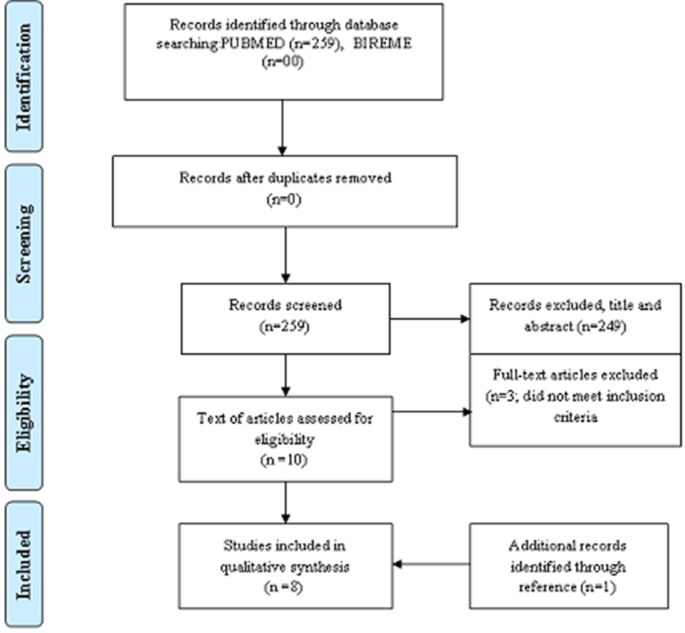

Of the 259 articles found, 10 were potentially eligible and selected for a more detailed review. Of these, only seven met the search criteria with the inclusion of another article selected from the list of references of the included studies (Figure 1).

FIG. 1.

SEARCH AND SELECTION OF STUDIES FOR SYSTEMATIC REVIEW ACCORDING TO PRISMA (PREFERRED REPORTING OF SYSTEMATIC REVIEWS AND META-ANALYSES [22]

In regards to the assessment of the quality criteria examined in this review, the studies are linked chronologically in Table 1. These showed a methodological deficit, with only four studies meeting 50% or more of the criteria analysed.

TABLE 1.

QUALITY OF THE STUDIES INCLUDED IN THE SYSTEMATIC REVIEW

| AUTHOR, YEAR | LABORATORY MANAGEMENT | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Temperature | Lighting | Housing | Water and food nutrition | Ethical protocol | Randomization | Training adaptation | Pre-loading | |

| Viidik, 1967 [31] | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Woo et al., 1980 [35] | - | - | + | + | - | + | - | - |

| Woo et al., 1981 [34] | - | - | + | + | - | + | + | + |

| Sommer et al., 1987 [27] | - | - | - | - | - | - | + | - |

| Simonsen et al., 1995 [26] | - | - | - | - | - | - | + | + |

| Viidik et al., 1996 [32] | + | + | + | + | - | - | - | - |

| Nielsen et al., 1998 [23] | + | + | + | + | - | - | - | - |

| Legerlotz et al., 2007 [20] | - | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

The characteristics of the samples analysed in this review are presented in chronological order in Table 2. Of these, a total of 384 animals from all the studies were analysed. In one study, the number of animals belonging to the treatment group was not reported, but only the total number of animals used, 192 [27].

TABLE 2.

CHARACTERISTICS OF THE STUDIES ELIGIBLE FOR THE REVIEW IN CHRONOLOGICAL ORDER

| AUTHOR YEAR | SAMPLE | GENDER | SAMPLE AGE | TENDON | PHYSICAL ACTIVITY | PHYSICAL PROTOCOL |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Viidik,1967 [31] | 13 control rabbits(CG);15 trained rabbits(TG) | -Gender not indicated | Not informed | -Tibialis posterior-Peronei | Treadmill | 40 weeks of training. How the training was carried out was not informed |

| Woo et al.,1980 [35] | 4 control pigs (CG); 5 trained pigs (GT) | Yucatan swine Males and females | 12 months old | -Digital extensors | Treadmill | Animals trained 8 months in a circular track and 4 months on a motorized treadmill. One hour per day at 1.6 m/s and an additional 30 minutes per day at 2.2 m/s, 5 days a week. A training of 12 months’ duration. |

| Woo et al.,1981 [34] | 4 control pigs (CG); 5 trained pigs (TG) | Yucatan swine Males and females | 12 months old | -Digital flexor | Treadmill | Conditioning during 1 month, 5 days a week, at 5km/h during 20 minutes. After the 3 week, the duration and velocities were increased to 60 minutes at 6km/h. Over the next 8 months, the animals trained for 60 min/day at 6km/h with an additional 30min/day at 8 km/hr. |

| Sommer,1987 [27] | Division by groups not reported; total of 192 rats | Wistar rats Males | 4 months old at the start of training | -Achilles tendon | Treadmill | The groups of animals (except control) were subjected to the same progressive race until the 8th week. After the 8th week, the animals were divided into speed training, endurance and speed, and endurance only. |

| Simonsen et al.,1995 [26] | 19 control rats (CG); 6 rats trained with force (FTG) and 5 rats trained with swimming (STG) | Wistar rats Males | CG -9 months old, STG and FTG - 24 months old STG and FTG - 29 months old On the day of sacrifice | -Achilles tendon | Swimming | 1st week – 4 days of training for 30, 45, 60 and 75 minutes. In the subsequent 15 weeks, 90 minute trainings were conducted, 4 times a week without extra loads. |

| Viidik et al.,1996 [32] | 26 healthy control rats (CG); 18 trained rats (TG) and 20 young control rats (YCG) | Sprague-Dawley rats Males | CG – 23 months old TG – 23 months old YCG – 5 months old On the day of sacrifice | Tail tendon | Treadmill | Two training sessions per day, 5 times a week, for 18 months, with a duration of 20 minutes for each session at a speed of 20 m/s. |

| Nielson et al.,1998 [23] | 21 healthy control rats (CG); 17 trained rats (TG) and 20 young control rats (YCG) | Sprague-Dawley rats Males | CG – 23 months old TG – 23 months old YCG – 5 months old On the day of sacrifice | -Tibialis anterior -Flexor digitorum longus | Treadmill | Two training sessions per day, 5 times a week, for 18 months, with a duration of 20 minutes for each session at a speed of 20 m/min. |

| Legerlotz et al.,2007 [20] | 20 healthy control rats (CG) and 20 rats trained with running (RTG), 24 weight trained rats (WTG) | Sprague-Dawley rats Females | 10 weeks old at the start of training | -Achilles tendon | Running Wheel | The animals ran freely for 12 weeks, maintaining an average daily distance of 10.1±2.9 km/day. |

One study did not report the gender of species studied or the age of the animals [31]. As for the tendon chosen, the Achilles was the most frequent in the eligible studies.

Concerning the modality of physical activity used in the studies, racing was prevalent, being replaced by swimming without load in the study by Simonsen and collaborators [26]. Two studies presented a third group of animals subjected to resistance training (anaerobic exercises of force) [20, 26]. With respect to the training time, the studies ranged from three to 18 months depending on the protocol used in each study (Table 2).

The relationship of the variables analysed and the results of the eight studies included in this review are described in Table 3. One of the studies [31] had a significance level (2p = 0.1) different from those used by the other studies (p = 0.05) and the study of Sommer and collaborators [27] did not report the statistical value of results found. The elastic modulus presented contradictory results in two studies that found changes in this parameter [31, 32], while an increase in the ultimate load supported by the tendon in the mechanical test was found in three [26, 34, 35] of the five surveys that analysed this outcome. The transverse section of the tendon had an increased value in two [27, 34] of the four studies that investigated this variable.

TABLE 3.

CHARACTERISTICS OF THE ELIGIBLE STUDIES IN TERMS OF THE VARIABLES ANALYZED

| AUTHOR YEAR | ULTIMATE LOAD | STRAIN | TRANSVERSE SECTIONAL AREA | ELASTIC MODULUS | ULTIMATE TENSILE STRESS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Viidik, 1967 [31] | Ø | Ø | NA | TG 703.4±26.5 Mpa CG 637±19.6 Mpa 2p < 0.10 | NA |

| Woo et al., 1980 [35] | *TG ↑p< 0.005 | *TG ↓p< 0.005 | *TG ↑p< 0.005 | NA | *TG ↑p< 0.005 |

| Woo et al., 1981 [34] | TG 1.95±0.06 103 N CG 1.63±0.07 103 N p < 0.005 | Ø | Ø | NA | Ø |

| Sommer, 1987 [27] | NA | NA | TG 1.72 ± 0.36 mm2CG 1.55±0.35 mm2p- not reported | NA | TG 50.7±13.5 MPa CG 55.8±11.1 MPa p- not reported |

| Simonsen et al., 1995 [26] | TG-56.8 N CG- 45 N p = 0.01 | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Viidik et al., 1996 [32] | NA | Ø | NA | TG 350.1±21.9 MPa CG 413.4±9.4 MPa p < 0.001 | TG 457.2±21.9 MPa CG 534±17 MPa p < 0.05 |

| Nielson et al., 1998 [23] | NA | Ø | NA | Ø | Ø |

| Legerlotz et al., 2007 [20] | Ø | Ø | Ø | Ø | Ø |

Note: value not reported

N – Newtons; MPa – Mega Pascal; mm2- square millimeters; Ø – no significant difference; NA- not analyzed; TG- trained group; CG – control group

DISCUSSION

Research on experimental animals has been viewed as a prerequisite for designing studies in humans, because it helps the scientific community in the understanding of diseases and the effect of interventions on metabolism in general.

Research through translational studies is a striking example of the connection of studies and laboratory discoveries being transformed into tools or means of targeted treatments in clinical studies. In this way, basic research fulfils not only the role of uncovering new discoveries through animal models, but also of enhancing and promoting knowledge applicable in the future to patients and public health [4, 24].

Despite this scientific momentum, research involving animal experimentation has shown shortcomings in methodological conceptions, compromising the accuracy and the transition of these findings to clinical research [11].

The aim in this study, of assessing changes in the biomechanical characteristics and structural properties of the tendon of animals subjected to aerobic training, by means of a systematic review, found differences in the methodology of the studies, as well as contradictory results regarding the effect of the training intervention.

With regard to the primary outcomes, this research found a tendency for increased ultimate load supported by the tendons of animals that have undergone training in addition to conflicting results regarding the elastic modulus. The former can be justified by the increase of organic components (e.g. collagen) in the tendon structure when subjected to physical training [35], while the latter finding requires better biomechanical research in view of the disparity of outcomes.

Concerning the secondary outcomes, the ultimate stress produced controversial results when subjected to physical training, while tendon strain showed biomechanical changes, in only one study, reporting a decrease in this parameter that can be confirmed by increased percentage of collagen fibres examined biochemically by the same author. On the other hand, physical training was able to promote an increase in transverse section area, making it one of the factors responsible for tendon plasticity. However, the diverse methods of evaluation used in the absence of a gold standard of benchmarks can derail the end result, making it inconclusive.

Nevertheless, looking at the article which best managed the risks of biases [20], it was not possible to detect any significant change resulting from physical training both in structure and in the biomechanical properties of the tendon of the sample in question.

A systematic review has as its main focus not only to bring together major works involving major changes in structural and biomechanical properties of tendons in experimental animals submitted to aerobic physical training, but also to examine the methodological process on which the articles were based to assess the trustworthiness of the results found, whether they be positive or negative.

Among the methodological findings, only one paper reported submission to an ethics committee for the development of a study using experimental animals. Approval by a committee specialized in the management of these specimens is necessary in order that the research maintain proper internal validity and a reproducible pattern of study, in addition to not causing mistreatment. Despite the fact that the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals was created in 1963 and is widely used as a basic reference in experimentation [16], only one article [20] of this review reported the approval of the research protocol by a committee specialized in animal studies.

The conflicting results found in the literature, primarily the discordant ones, deserve a careful analysis of the methodologies which were undertaken in order to find fault or even divergent points to justify differentiated results. In this way, the information about the management of experimental animals, including the environment in which they were kept during development of the experiment, nutrition, water supply, lighting, temperature, among others, are all of extreme importance for the understanding of the experimental process to which the animals were subjected [12]. Despite this premise only two studies reported the temperature at which the animals were kept [23, 32] and only three reported the light/dark cycle to which the animals were subjected [20, 23, 32].

The temperature and the light/dark cycle under which the animals are kept can alter metabolic rates, as well as cardiac pressure and frequency [3, 21, 29], which in animals subjected to aerobic training can affect animal performance and compromise the results of the activity. In addition, changes in the light/dark cycle may also affect corporal metabolism (body weight, ingested liquid, excretion) and animal behaviour by making it more aggressive [30] and without predisposition for training.

In our review, three studies did not report the manner in which the animals were kept, singly or in groups [26, 27, 31]. In research that requires the use of a large number of animals, their grouping in common or individual environments completely influences their performance and adaptation before and after the interventions. The animal population in a micro-environment can influence the central hormonal responses [28] and hierarchical dominance behaviour [2], or even influence the immune system when the animals are isolated. These differences make comparisons unreliable between studies using isolated animals with those using groups [5].

In an attempt to keep a sensible default, as regards the methodology employed in experimental research, the risks of biases in managing basic situations such as the amount of food and water available to the animal or even the type of food that is made available, cannot be neglected. Food restriction or changes in the supply of food can result in elevation of corticosteroids with consequent changes in behaviour and stress [14]. In addition, the need to maintain the same kind of food (feed) becomes necessary in order to provide the same amount of proteins, carbohydrates and lipids. However, three studies [26, 27, 31] did not report the necessary information about nutrition and supply of water and food.

In the case of assigning a new activity to the daily life of animals, it is imperative to allow an adjustment period for the animals to become familiar with the space in which the procedure is performed in order to avoid any kind of stress to the animal. In only four works was a period of adaptation of the animals to the training performed [20, 26, 27, 34].

The lack of adaptation of animals to the exercise can affect the final results of the research, as can the method used for preparing the test of structures evaluated by the study. When it comes to biomechanical testing of soft tissues such as tendon, after the storage period of the anatomical part or even in the use of fresh tissue, the preconditioning of the tendon structure has become a rule [8]. This preconditioning generates a baseline load level used to test the biomechanical properties, with the procedure adopted appropriate for the type of tissue used [9]. In this review, only three studies [20, 26, 34] conducted these adjustments before the mechanical test.

In this review we found studies that have identified changes of biomechanical properties and others where exercise has not imposed any modifications. Studies with greater internal control are needed to fill the existing scientific gap regarding the real contribution of physical exercise to the biomechanical behaviour of the tendon.

CONCLUSIONS

Physical training performed in a structured way with the imposition of overloads seems to be able to promote changes in tendon structure of experimental models by increasing the ultimate load supported. However, the results of the influence of physical training on the parameters of elastic modulus, strain, transverse section area and ultimate stress remain controversial and inconclusive. Such a conclusion must take into account the low methodological control of the studies included in this review. Thus, the implications of these findings for future research in animal models include greater methodological control, specifically with appropriate randomization of samples, greater control of the conditions of keeping animals and principally in the form of evaluation of biomechanical characteristics.

REFERENCES

- 1.Almeida-Silveira M.I, Lambertz D, Peârot C, Goubel F. Changes in stiffness induced by hindlimb suspension in rat Achilles tendon. Eur. J. Appl. Physiol. 2000;81:252–257. doi: 10.1007/s004210050039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Arndt S.S, Laarakker M.C, Van Lith H.A, Van Der Staay F.J, Gieling E, Salomons A.R, Van't Klooster J, Ohl F. Individual housing of mice Impact on behaviour and stress responses. Physiol. Behav. 2009;97:385–393. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2009.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Azar T.A, Sharp J.L, Lawson D.M. Effect of housing rats in dim light or long nights on heart rate. J. Am. Assoc. Lab. Anim. Sci. 2008;47:25–34. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Azevedo V.F. Medicina translacional: qual a importância para a prática reumatológica? Rev. Bras. Reumatol. 2009;49:81–83. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bartolomucci A, Palanza P, Sacerdote P, Ceresini G, Chirieleison A, Panerai A.E, Parmigiani S. Individual housing induces altered immunoendocrine responses to psychological stress in male mice. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2003;28:540–558. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4530(02)00039-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Buchanan C.I, Marsh R.L. Effects of exercise on the biomechanical, biochemical and structural properties of tendons. Comp. Biochem. Phys. A. 2002;133:1101–1107. doi: 10.1016/s1095-6433(02)00139-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Caspersen C.J.C, Powell K.E, Christenson G.M. Physical activity, exercise and physical fitness: definitions and distinctions for health-related research. Public Health Rep. 1985;100:126–131. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cheng S, Clarke E.C, Bilston L.E. The effects of preconditioning strain on measured tissue properties. J. Biomech. 2009;42:1360–1362. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2009.03.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Conza N. Part 3: Tissue preconditioning. Engeneering issues in experimental biomedicine series. Exp. Techniques. 2005;29:43–46. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cook J.L, Kiss Z.S, Ptasznik R, Malliaras P. Is vascularity more evident after exercise? Implications for tendon imaging. AJR Am. J. Roentgenol. 2005;185:1138–1140. doi: 10.2214/AJR.04.1205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dirnagl U. Bench to bedside: the quest for quality in experimental stroke research. J. Cerebr. Blood F. Met. 2006;26:1465–1478. doi: 10.1038/sj.jcbfm.9600298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ellery A.W. Guidelines for specification of animals and husbandry methods when reporting the results of animal experiments. Lab. Anim. 1985;19:106–8. doi: 10.1258/002367785780942714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Harthmann A.D, Angelis K.D, Costa L.P, Senador D, Schaan B.D, Krieger E.M, Irigoyen M.C. Exercise training improves arterial baro-and chemoreflex in control and diabetic rats, Auton. Neurosci. 2007;133:115–120. doi: 10.1016/j.autneu.2006.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Heiderstadt K.M, Mclaughlin R.M, Wrighe D.C, Walker S.E, Gomez-Sanchez C.E. The effect of chronic food and water restriction on open-field behaviour and serum corticosterone levels in rats. Lab. Anim. 2000;34:20–28. doi: 10.1258/002367700780578028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hooijmans C.R, Leenaars M, Ritskes-Hoitinga M. A gold standard publication checklist to improve the quality of animal studies, to fully integrate the three Rs, and to make systematic reviews more feasible. ATLA. 2010;38:167–182. doi: 10.1177/026119291003800208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Institute of Laboratory Animals Resourses (ILAR), Commission on Life Sciences, National Research Council. Manual sobre Cuidados e Usos de Animais de Laboratório/ tradução Guillermo Rivera; Goiânia: AAALAC e COBEA; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kemi O.J, Wisloff U. Mechanisms of exercise-induced improvements in the contractile apparatus of the mammalian myocardium. Acta Physiol. 2010;199:425–439. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-1716.2010.02132.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Langberg H, Olesen J.L, Gemmer C, Kjær M. Substantial elevation of interleukin-6 concentration in peritendinous tissue, in contrast to muscle, following prolonged exercise in humans. J. Physiol. 2002;542:985–990. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2002.019141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Langberg H, Rosendal L, Kjær M. Training-induced changes in peritendinous type I collagen turnover determined by microdialysis in humans. J. Physiol. 2001;534:297–302. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2001.00297.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Legerlotz K, Schjerling P, Langberg H, Bruggemann G.-P, Niehoff A. The effect of running, strength, and vibration strength training on the mechanical, morphological, and biochemical properties of the Achilles tendon in rats. J. Appl. Physiol. 2007;102:564–572. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00767.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Li P, Sur S.H, Mistlberger R.E, Morris M. Circadian blood pressure and heart rate rhythms in mice. Am. J. Physiol. 1999;276:500–504. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1999.276.2.R500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Liberati A, Altman D.G, Tetzlaff J, Mulrow C, Gøtzsche P.C, Ioannidis J.P.A, Clarke M, Devereaux P.J, Kleijnen J, Moher D. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: explanation and elaboration. BMJ. 2009:339. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b2700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nielsen H.M, Skalicky M, Viidik A. Influence of physical exercise on aging rats. III. Life-long exercise modifies the aging changes of the mechanical properties of limb muscle tendons. Mech. Ageing Dev. 1998;100:243–260. doi: 10.1016/s0047-6374(97)00147-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Oliveira L.V.F. Da bancada ao leito: a partir de um diagnóstico preciso para o tratamento adequado. O uso crescente da pesquisa translacional. ConScientiae Saúde. 2009;8:545–547. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rennie M.J. Body maintenance and repair: how food and exercise keep the musculoskeletal system in good shape. Exp. Physiol. 2005;90:427–436. doi: 10.1113/expphysiol.2005.029983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Simonsen E.B, Klitgaard H, Bojsen-Moller F. The influence of strength training, swim training and ageing on the achilles tendon and m. soleus of rat. J. Sports Sci. 1995;13:291–295. doi: 10.1080/02640419508732242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sommer H.M. The biomechanical and metabolic effects of a running regime on the achilles tendon in the rat. Int. Orthop. 1987;2:71–75. doi: 10.1007/BF00266061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Stranahan A.M, Khalil D, Gould E. Social isolation delays the positive effects of running on adult neurogenesis. Nat. Neurosci. 2006;9:526–533. doi: 10.1038/nn1668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Swoap S.J, Overton J.M, Garber G. Effect of ambient temperature on cardiovascular parameters in rats and mice: a comparative approach. Am. J. Physiol. 2004;287:391–396. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00731.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Van Der Meer E, Van Loo P.L.P, Baumans V. Short-term effects of a disturbed light–dark cycle and environmental enrichment on aggression and stress-related parameters in male mice. Lab. Anim. 2004;38:376–383. doi: 10.1258/0023677041958972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Viidik A. The effects of training on the tensile strength of isolated rabbits tendons. Scand. J. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 1967;1:141–147. doi: 10.3109/02844316709022844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Viidik A, Nielsen H.M, Skalicky M. Influence of physical exercise on aging rats: II. Life-long exercise delays aging of tail tendon collagen. Mech. Ageing Dev. 1996;88:139–148. doi: 10.1016/0047-6374(96)01729-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wang J.H.C. Mechanobiology of tendon. J. Biomech. 2006;39:1563–1582. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2005.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Woo S.L-Y, Gomez M.A, Amiel D, Ritter M.A, Gelberman R.H, Akeson W.H. The effects of exercise on the biomechanical and biochemical properties of swine digital flexor tendons. J. Biomech. Eng. 1981;103:51–56. doi: 10.1115/1.3138246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Woo S.L-Y, Ritter M.A, Amiel D, Sanders T.M, Gomez M.A, Kuei S.C, Garfin S.R, Akeson W.H. The biomechanical and biochemical properties of swine tendons long term effects of exercise on the digital extensors. Connect. Tissue Res. 1980;7:177–183. doi: 10.3109/03008208009152109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]