Abstract

Background

Early, intensive treatment of rheumatoid arthritis (RA) with the combination of (initially high dose) prednisolone, methotrexate and sulfasalazine (COBRA therapy) considerably lowers disease activity and suppresses radiological progression, but is infrequently prescribed in daily practice. Attenuating the COBRA regimen might lessen concerns about side effects, but the efficacy of such strategies is unknown.

Objective

To compare the ‘COBRA-light’ strategy with only two drugs, comprising a lower dose of prednisolone (starting at 30 mg/day, tapered to 7.5 mg/day in 9 weeks) and methotrexate (escalated to 25 mg/week in 9 weeks) to COBRA therapy (prednisolone 60 mg/day, tapered to 7.5 mg/day in 6 weeks, methotrexate 7.5 mg/week and sulfasalazine 2 g/day).

Method

An open, randomised controlled, non-inferiority trial in 164 patients with early active RA, all treated according to a treat to target strategy.

Results

At baseline patients had moderately active disease: mean (SD) 44-joint disease activity score (DAS44) 4.13 (0.81) for COBRA and 3.95 (0.9) for COBRA-light. After 6 months, DAS44 significantly decreased in both groups (–2.50 (1.21) for COBRA and –2.18 (1.10) for COBRA-light). The adjusted difference in DAS44 improvement between the groups, 0.21 (95% CI –0.11 to 0.53), was smaller than the predefined clinically relevant difference of 0.5. Minimal disease activity (DAS44 <1.6) was reached in almost half of patients in both groups (49% and 41% in COBRA and COBRA-light, respectively).

Conclusions

At 6 months COBRA-light therapy is most likely non-inferior to COBRA therapy.

Clinical Trial Registration Number

55552928.

Keywords: Early Rheumatoid Arthritis, Treatment, DMARDs (synthetic), Corticosteroids

Introduction

Early and intensive treatment of rheumatoid arthritis (RA) has significantly altered the short-term and long-term outcome of RA patients.1–3 Targeting treatment to decrease disease activity immediately after diagnosis has favourable effects on disease activity, physical functioning and (radiographic) joint damage progression.4–8 Combination therapy of disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs (DMARD), usually including prednisolone, has proved to be superior to monotherapy for suppressing disease activity and radiological progression.3 6 9–12 This was observed in the COBRA trial (COmbinatietherapie Bij Reumatoide Artritis) in which patients were treated with sulfasalazine (SSZ), methotrexate and initially high-dose prednisolone (60 mg/day). Disease activity decreased and radiological progression was suppressed, and these effects were sustained after long-term follow-up.9 13 14 Furthermore, in the BeSt study it was demonstrated that treatment with COBRA therapy is as effective as combination therapy with methotrexate and initial anti-tumour necrosis factor treatment (infliximab) with respect to clinical improvement and prevention of radiographic damage, and superior to initial monotherapy with methotrexate and step-up therapy in the first months of treatment.6

Despite confirmed clinical effectiveness, safety and cost-effectiveness, rheumatologists infrequently prescribe COBRA therapy to patients for the following reasons: (1) fear of possible side effects of high-dose prednisolone; (2) complexity of the treatment schedule; (3) the large number of pills that patients receive and physicians should prescribe; and 4) concerns about possible counteracting interactions between methotrexate and sulfasalazine.15 Therefore, a treat-to-target strategy combining a lower dose of prednisone, without sulfasalazine and with a higher dose of methotrexate, was designed, termed ‘COBRA-light’. The objective of this study was to compare the effect of COBRA-light to COBRA on clinical and radiological outcomes in early RA. This report focuses on whether COBRA-light therapy is non-inferior to COBRA therapy in the primary clinical outcome set at 26 weeks of treatment.

Patients and methods

Patients

The COBRA-light study was an investigator-driven study: initiated, designed and conducted by rheumatologists working at the VU Medical Center, Reade and Westfriesgasthuis in Amsterdam and Hoorn, The Netherlands. Patients with early RA according to the revised American College of Rheumatology (ACR) criteria,16 were recruited between March 2008 and March 2011. Other inclusion criteria were: age 18 years and over, disease duration 2 years or less, currently active disease as shown by at least six swollen and tender joints, plus either an erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) of 28 mm/h or greater or a global health score of 20 mm or greater on a 0–100 mm visual analogue scale. Exclusion criteria included: previous treatment with glucocorticoids or DMARD other than antimalarial agents, uncontrolled diabetes mellitus, heart failure (New York Heart Association class 3–4), uncontrolled hypertension, ALT or AST level more than three times the upper limit of normal, reduced renal function (serum creatinine level >150 µmoles/l), contraindications for glucocorticoids and a positive tuberculin skin test. The eligibility criteria strongly resemble earlier trials establishing the efficacy of COBRA.6 9 The medical ethics committee at each participating centre approved the protocol and the study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki/good clinical practice. All patients gave written informed consent before inclusion.

Treatment allocation and intervention

The COBRA-light study was a randomised, open, multicentre trial comparing two treatment schedules for the treatment of early RA (http://www.controlled-trials.com; ISRCTN55552928). Patients were randomly assigned to either COBRA therapy or COBRA-light therapy using sequentially numbered envelopes containing the allocated treatment group. Online randomisation software was used to obtain variable blocks of six, stratified per centre. After checking eligibility and informed consent, the study physician entered each patient into the study. For some patients the assigned treatment was started after 1 week to allow baseline measurements of insulin resistance (results reported separately).17

This study included a strict treatment regime during 1 year and a second year of follow-up.

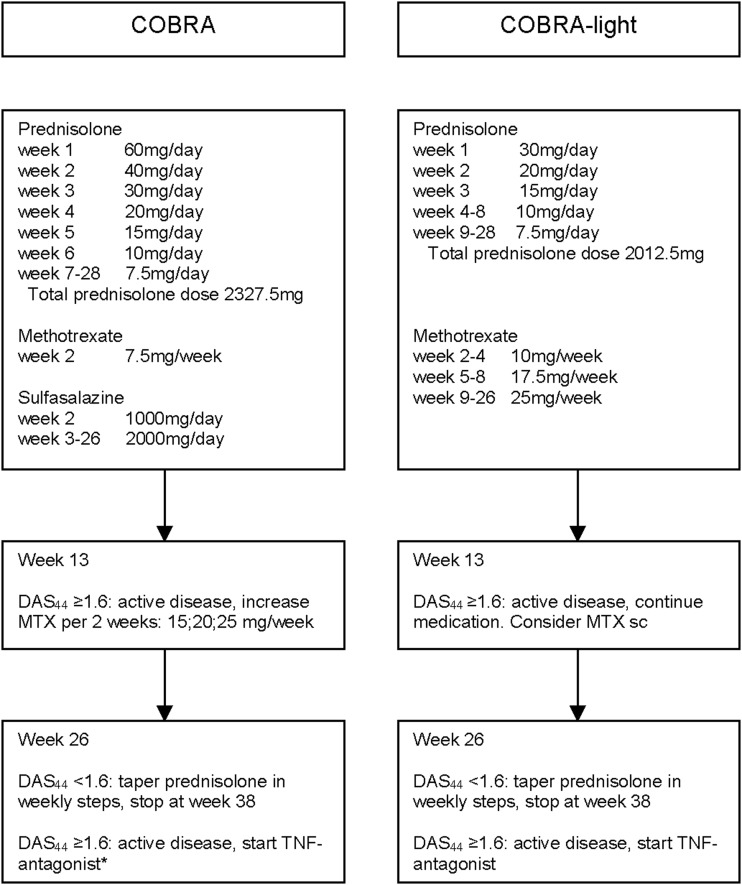

Patients assigned to COBRA therapy started with prednisolone 60 mg/day, tapered to 7.5 mg/day in 6 weeks, methotrexate 7.5 mg/week and sulfasalazine 1 g/day, increased to 2 g/day after 1 week (figure 1) according to the COBRA study.6 The decision to adjust medication was based on the disease activity score in 44 joints (DAS44), including the Ritchie articular index, assessed every 3 months. The primary treatment goal was minimal disease activity, at that time defined as DAS44 less than 1.6. The protocol required an increase of the methotrexate dose to 25 mg/week after 13 weeks of treatment if the DAS44 was 1.6 or over. Patients receiving COBRA-light therapy started with prednisolone 30 mg/day, tapered to 7.5 mg/day in 9 weeks and methotrexate 10 mg/week with stepwise increments in all patients to 25 mg/week in 9 weeks; the protocol required the treating physician to consider parenteral methotrexate after 13 weeks if the DAS44 was 1.6 or greater (figure 1). All patients received folic acid 5 mg/week and daily calcium/vitamin supplementation. Bisphosphonates were prescribed according to the guidelines for glucocorticoid-induced osteoporosis.18 Concomitant treatment with non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and intra-articular injections with glucocorticoids during the study were permitted. For analyses, it was assumed that all intra-articular glucocorticoid injections given less than 3 months before the next visit influenced the disease activity calculations. Therefore, the injected joint was scored as being tender and swollen. If an intramuscular glucocorticoid injection was given within 4 weeks before a next visit, the disease activity calculation was recorded as missing.

Figure 1.

Treatment protocol COBRA-light study. *Methotrexate must first be increased to 25 mg/week. DAS44, 44-joint disease activity score; MTX, methotrexate; sc, subcutaneous; TNF, tumour necrosis factor.

In general, in the case of an adverse event, the responsible drug(s) were reduced to the lowest tolerable dose. Additional options for methotrexate included subcutaneous injections if patients experienced gastrointestinal side effects and finally patients could switch to leflunomide if they remained intolerant to methotrexate.

Assessment of endpoints

Every 3 months independent research nurses and (for VU Medical Center) study physicians performed the assessments. The primary outcome was the change in DAS44 after 26 weeks of treatment compared with baseline (ΔDAS44). Secondary outcomes included the proportions of patients achieving minimal disease activity according to DAS44 criterion (DAS44 1.6) and the new ACR/European League Against Rheumatism (EULAR) criteria (Boolean approach).19 20 Other secondary outcomes were changes in core set variables, the EULAR and ACR response criteria and physical function as measured by the Dutch version of the health assessment questionnaire (HAQ).21 22 All protocol violations were recorded. Protocolised treatment deviations were recorded separately. Major protocol violations were defined as any unapproved changes in the treatment protocol or procedures that could affect the completeness, accuracy, reliability and integrity of the study data; this was adjudicated by an independent committee of two rheumatologists not involved in the execution of the study.

Safety

During follow-up safety was monitored at each study visit by active solicitation: patients were interviewed on the presence of adverse effects following a detailed list. In addition, laboratory monitoring comprised a complete blood cell count, serum levels of ALT, alkaline phosphatase, creatinine, electrolytes, glucose and lipids. All adverse events and subsequent treatment adjustments were recorded. A serious adverse event was defined as any untoward medical occurrence that resulted in death, was life-threatening, (planned) inpatient hospitalisation or prolongation of existing hospitalisation, resulted in persistent or significant disability/incapacity, or (planned) intervention to prevent permanent impairment or damage. An independent committee identified all serious events and assessed their potential relationship with treatment.

Statistical analysis

The primary outcome of this trial was the mean ΔDAS44 after 26 weeks. The limit for non-inferiority was set at a difference in change of 0.5 points. Sample size calculations showed that 142 patients would be needed to obtain 80% power, with a two-sided significance level of 5%, to detect this difference. The target inclusion was set at 160 to compensate for loss to follow-up. Data are presented as mean values±SD or as median (IQR) in the case of skewed distribution. Analyses were performed by a modified intention to treat (ITT) protocol, including all patients who received at least one dose of the allocated treatment schedule. Two patients (one in each group) were lost to follow-up at weeks 13 and 16, respectively, and their missing data were imputed as follows: the mean change in DAS44 between week 13 and week 26 of all patients was used to calculate the missing DAS44 scores at week 26 for the individual patient. Post hoc, after checking results, DAS44 calculations with C-reactive protein (CRP) were performed to investigate the effect of different acute phase proteins.

All outcome variables with Gaussian distribution were analysed by linear regression. The primary outcome was analysed with ΔDAS44 as outcome and treatment group and baseline DAS44 as explanatory variables. Non-normally distributed parameters were first log-transformed and also analysed by linear regression. Categorical variables were tested by the χ2 test. Subgroup analyses were performed to explore the effect of protocol deviations on the primary outcome. All statistical analyses were run on SPSS for Windows V.15.0. A two-sided p<0.05 was considered statistically significant. For the primary outcome, ΔDAS44, results document whether the difference between the groups and its 95% CI exceeds the preset non-inferiority boundary. For secondary outcomes, for example, the difference in disease activity score components, the results of traditional statistical tests of the null hypothesis of no difference are reported.

Results

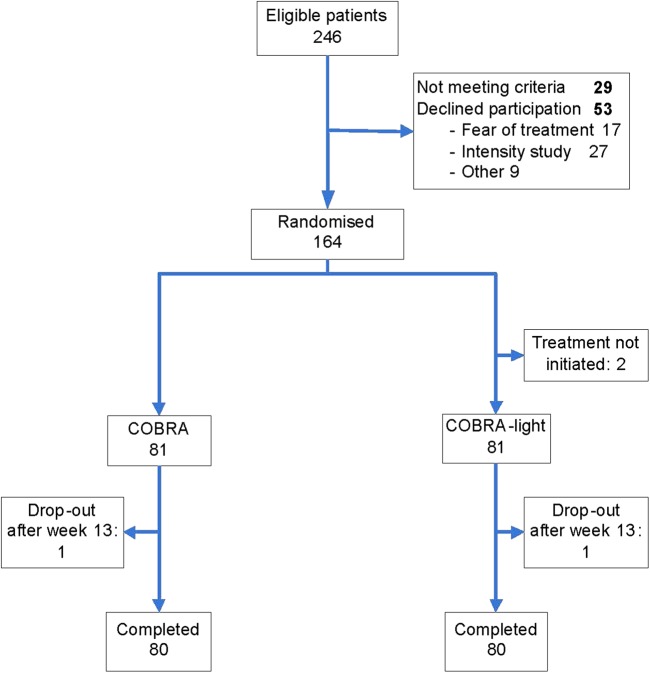

In total, 164 patients were randomly assigned for treatment with COBRA (n=81) or COBRA-light (n=83) (figure 2). Of all patients screened (n=246), 33% were not included because they did not meet the entry criteria or declined participation. The predominant reason to decline was the intensity of the study rather than the treatment. Two patients did not initiate treatment and dropped out immediately after randomisation. These patients were excluded from the ITT analyses. In addition, two patients (one in each arm) stopped trial treatment and were lost to follow-up at 13 and 16 weeks due to adverse events (myocardial infarction in COBRA and manic episode in COBRA-light, respectively). From these patients no clinical data were available at week 26, but both were still alive. At baseline the groups were mostly well matched in demographic and disease characteristics, but the baseline DAS44 was somewhat higher in the COBRA group: mean 4.13 (SD 0.81) versus 3.95 (0.9) in the COBRA-light group (table 1). Median disease duration was 16 weeks (IQR 8–30). The majority of patients (71%) were rheumatoid factor (RF) or anti-cyclic citrullinated peptide (CCP) positive, and 51% of the patients were positive for both factors. In total, three patients had used hydroxychloroquine before inclusion (two in COBRA and one in COBRA-light). The four patients prematurely discontinuing trial treatment were older (median 64 years, IQR 54–70) and had a higher HAQ score at baseline (median 1.9, IQR 1.4–2.3) compared to the other patients.

Figure 2.

Flow-chart COBRA-light study.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics

| Cobra (n=81) | Cobra-light (n=83) | |

|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 53 (±13) | 51 (±13) |

| Women, n (%) | 54 (67%) | 58 (70%) |

| Disease duration (weeks) | 16 (9–28) | 17 (8–33) |

| RF positive, n (%) | 47 (58%) | 48 (58%) |

| Anti-CCP positive, n (%) | 50 (62%) | 55 (66%) |

| Erosive disease, n (%)* | 8 (10%) | 14 (17%) |

| DAS44 | 4.13 (±0.81) | 3.95 (±0.89) |

| DAS44 CRP | 3.98 (±0.73) | 3.83 (±0.85) |

| DAS28 | 5.67 (±1.13) | 5.45 (±1.29) |

| Tender joints | 17 (12–24) | 16 (10–23) |

| Swollen joints | 13 (10–17) | 11 (9–14) |

| Ritchie articular index | 10 (7–13) | 11 (7–13) |

| HAQ | 1.36 (±0.66) | 1.37 (±0.71) |

| ESR, mm/h | 27 (15–45) | 27 (12–48) |

| CRP, mg/l | 13 (5–27) | 13 (4–31) |

| Patient assessment disease activity, mm (0–100) | 64 (43–76) | 68 (52–84) |

| Patient assessment of pain, mm (0–100) | 64 (46–76) | 59 (38–78) |

| Patient global assessment, mm (0–100) | 62 (48–75) | 60 (36–78) |

| Physician assessment disease activity, mm (0–100) | 50 (40–60) | 46 (38–59) |

Data are expressed as mean (±SD) or median (IQR).

*Erosive disease according to the in-house radiologist.

Tender joints=53 joints, swollen joints=44 joints, Ritchie articular index=53 joints.

Anti-CCP, anti-cyclic citrullinated peptide; CRP, C-reactive protein; DAS28, 28-joint disease activity score; DAS44, 44-joint disease activity score; ESR, erythrocyte sedimentation rate; HAQ, health assessment questionnaire; RF, rheumatoid factor.

Clinical outcomes

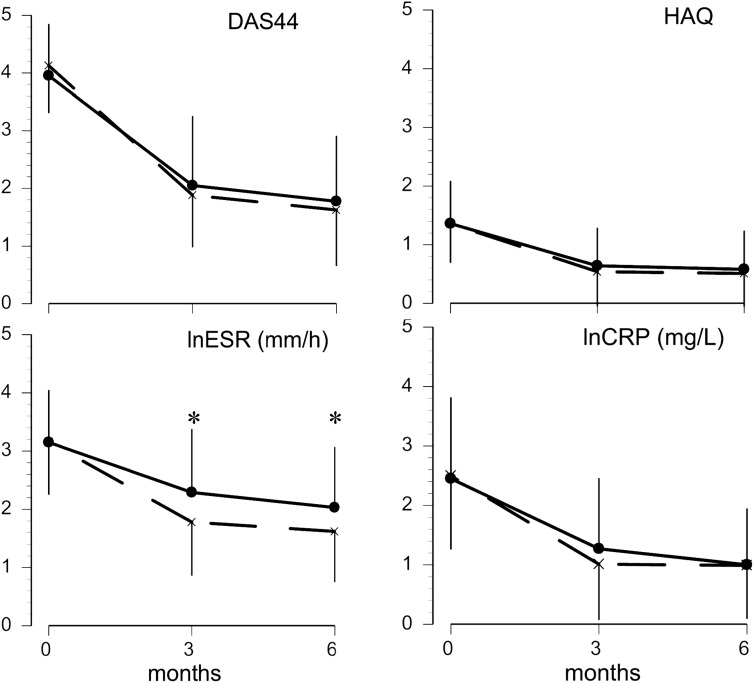

In both groups disease activity rapidly decreased, with most of the effect already reached at week 13 (figure 3): change in DAS44 at 26 weeks was –2.50 (1.21) for COBRA and –2.18 (1.10) for COBRA-light; between-group difference 0.33 (95% CI –0.03 to 0.68), that is, less than the prespecified non-inferiority boundary (table 2). This difference in ΔDAS44 decreased to 0.21 points (95% CI −0.11 to 0.53) after correction for baseline DAS44 values. The mean DAS44 at week 26 was 1.62 (0.96) for the COBRA arm and 1.78 (1.13) for the COBRA-light arm. After 13 weeks of treatment, 46 (57%) patients in the COBRA arm had a DAS44 of 1.6 or greater, and thus needed to intensify the treatment, compared to 45 (56%) patients in the COBRA-light arm.

Figure 3.

Mean change in outcomes of treatment. Data are expressed as mean (±SD). Dotted line represents COBRA and straight line represents COBRA-light. *p<0.05 compared with COBRA-light. Number of patients DAS44 COBRA: baseline, 81; week 13, 81; week 26, 81. COBRA-light: baseline, 81; week 13, 80; week 26, 81. Number of patients HAQ COBRA: baseline, 80; week 13, 80; week 26, 78. COBRA-light: baseline, 81; week 13, 79; week 26, 80. Number of patients ESR COBRA: baseline, 81; week 13, 80; week 26, 80. COBRA-light: baseline, 81; week 13, 78; week 26, 80. Number of patients CRP COBRA: baseline, 81; week 13, 81; week 26, 78. COBRA-light: baseline, 79; week 13, 78; week 26, 76. p Values: DAS44: baseline, p=0.2; week 13, p=0.3; week 26, p=0.37. HAQ: baseline, p=0.97; week 13, p=0.33; week 26, p=0.52. lnESR: baseline, p=0.94; week 13, p=0.002; week 26, p=0.006. lnCRP: baseline, p=0.82; week 13, p=0.21; week 26, p=0.94. CRP, C-reactive protein; DAS44, 44-joint disease activity score; ESR, erythrocyte sedimentation rate; HAQ, health assessment questionnaire; ln, natural logarithm.

Table 2.

Outcome at 26 weeks

| COBRA (n=81) | COBRA-light (n=81) | Unadjusted β (95% CI) | p Value | Adjusted* β (95% CI) | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Δ DAS44 | –2.50 (±1.21) | –2.18 (±1.1) | 0.33 (–0.03 to 0.68) | 0.08 | 0.21 (–0.11to 0.53) | 0.19 |

| AUC DAS44 | 62.1 (±17.6) | 64.0 (±25.4) | 2.2 (–4.5 to 9.0) | 0.52 | ||

| Δ DAS44 CRP | −2.15 (±1.09) | −2.10 (±1.09) | 0.04 (−2.9 to 0.38) | 0.79 | −0.06 (−0.36 to 0.23) | 0.68 |

| Δ HAQ | –0.8 (±0.6) | –0.8 (±0.7) | 0.1 (–0.2 to 0.3) | 0.61 | 0.1 (–0.1 to 0.2) | 0.49 |

| Δ Tender joints | –14.0 (±10.9) | –12.8 (±11.1) | 1.2 (–2.3 to 4.7) | 0.49 | 0.3 (–2.0 to 2.5) | 0.81 |

| Δ Swollen joints | –11.3 (±6.1) | –9.6 (±6.2) | 1.6 (–0.3 to 3.5) | 0.10 | 0.2 (–0.9 to 1.4) | 0.67 |

| Δ ESR, mm/h† | –21.5 (–37; −8) | –13.5 (–34; −4) | 1.5 (1.2 to 2.1) | 0.003 | 1.5 (1.2 to 2.0) | 0.002 |

| Δ CRP, mg/l† | –9.5 (–25; −1) | –8.5 (–29;-1) | 1.1 (0.7 to 1.6) | 0.67 | 1.0 (0.8 to 1.4) | 0.42 |

| Δ Patient VAS disease activity | –31 (±31) | –41 (±32) | –9.3 (–19.3 to 0.7) | 0.07 | –5.6 (–13.8 to 2.6) | 0.18 |

| Δ Patient VAS pain | –32 (±30) | –34 (±30) | –0.5 (–10.1 to 9.2) | 0.55 | –2.9 (–10.5 to 4.7) | 0.25 |

| Δ Patient VAS global health | –33 (±32) | –33 (±30) | –2.9 (–12.5 to 6.7) | 0.92 | –4.7 (–12.6 to 3.3) | 0.45 |

| Δ Physician VAS disease activity | –31 (±20) | –31 (±25) | –0.6 (–7.9 to 6.6) | 0.98 | –3.1 (–9.4 to 3.1) | 0.43 |

Data are expressed as mean (±SD) or median (IQR) change from baseline. Δ=change from baseline value. Significance between groups was tested with linear regression.

*Adjusted for baseline value.

†Regression based on LNESR and LNCRP.

anti-CCP, anti-cyclic citrullinated peptide; AUC, area under the curve; CRP, C-reactive protein; DAS44, 44-joint disease activity score; ESR, erythrocytesedimentation rate; HAQ, health assessment questionnaire; RF, rheumatoid factor; VAS, visual analogue scale.

We also show the analyses with a two-sided 90% CI.23 The difference in ΔDAS44 changes to 0.33 points (90% CI 0.11 to 0.71); adjusted for baseline DAS44: 0.21 points (90% CI −0.05 to 0.48). Extra analyses with DAS44 calculated with CRP show that there is nearly no difference between the groups. The ΔDAS44 is −2.15 (1.09) for COBRA and −2.10 (1.09) for COBRA-light. Therefore, a difference in ΔDAS44 of 0.044 (95% CI −0.29 to 0.38), and adjusted for baseline DAS44 CRP: −0.06 (95% CI −0.36 to 0.23).

There were no significant differences between the treatment groups with respect to all secondary outcome measures at week 26 (figure 3), except for ESR, which was lower in the COBRA arm (p=0.003). There were no statistically significant differences in the proportion of patients reaching minimal disease activity (DAS44 <1.6); 49% COBRA versus 41% COBRA-light, and remission according to the ACR/EULAR Boolean remission criteria: 16% COBRA vs 20% COBRA-light. The percentage of patients with good EULAR response after 13 weeks was 63% in the COBRA arm and 47% in the COBRA-light arm, which increased to 75% and 65% (in COBRA and COBRA-light, respectively) after 26 weeks. A limited number of patients fulfilled the EULAR non-response criteria: 4% versus 11% after 13 weeks and 6% versus 11% after 26 weeks for COBRA and COBRA-light, respectively. An ACR20 response was achieved in 74% COBRA versus 72% COBRA-light patients, an ACR50 response in 57% versus 62% and an ACR70 response in 38% versus 49%, respectively. None of these differences reached statistical significance. During follow-up, one COBRA-light patient received an intramuscular injection with glucocorticoids 2 weeks before the 13-week assessment and three COBRA-light patients received an intra-articular injection.

In the COBRA arm 47 (58%) patients needed intensification (eg, increase of methotrexate to full dose) at week 13 due to high disease activity. An increase in methotrexate resulted in a mean (SD) ΔDAS44 of –0.67 (0.8) at week 26, compared with a mean (SD) ΔDAS44 of 0.03 (1.1) in patients who had a DAS44 of 1.6 or greater but without intensification (eg, protocol violation). After 26 weeks the mean methotrexate dose was 15.6 mg/week in the COBRA arm; 24.4 mg/week after intensification and 7.5 mg/week in the remainder. In three (4%) COBRA-light patients the treatment was intensified by parenteral methotrexate. The mean methotrexate dose was 24 mg/week in the COBRA-light arm. No patients were lost to follow-up due to loss of efficacy.

Adverse events

On active solicitation the majority of patients reported at least one adverse event: COBRA 94% and COBRA-light 90%. These were mostly mild gastrointestinal problems (42% in both groups), infections (42% in COBRA and 40% in COBRA-light) or skin problems (37% and 43% in COBRA and COBRA-light, respectively). Six per cent of the COBRA patients and 5% of the COBRA-light patients did not reach the maximal dose of methotrexate due to elevated liver enzymes or gastrointestinal complaints. During the 26 weeks of treatment mean weight gain was 1.3 (3.1) kg for COBRA and 1.2 (3.4) kg for COBRA-light (p=0.90). In total, seven patients (9%) in the COBRA arm had an increase of more than 5 kg compared with 14 patients (18%) in the COBRA-light arm. In the COBRA arm two patients were newly diagnosed with diabetes type II and needed treatment with oral antidiabetic drugs. Three patients needed treatment for hypertension (one in the COBRA arm and two in the COBRA-light arm).

Serious adverse events occurred in three COBRA patients (myocardial infarction, planned cataract operation, and a planned operation of the cervical spine) and in six COBRA-light patients (planned knee replacement, planned hallux valgus surgery, planned varicose vein surgery, planned control coloscopy for diverticulosis, hospitalisation for arrhythmia, and a manic episode).

Protocol violations

More protocol violations occurred in COBRA than in COBRA-light: 24 versus 7%. Six COBRA patients and two COBRA-light patients had a major protocol violation (table 3). These patients were included in the primary analysis. Excluding patients with major protocol violations resulted in a larger improvement in DAS44 (−2.57 (1.19)) in patients treated with COBRA, while the results for COBRA-light remained more or less the same (−2.16 (1.09)). The difference in ΔDAS44 increased to 0.41 points, which was significantly different (95% CI 0.05 to 0.77); adjusted for baseline DAS44: 0.21 (95% CI −1.12 to 0.53).

Table 3.

Protocol deviations

| COBRA (n=81) | COBRA-light (n=81) | |

|---|---|---|

| Protocolised treatment deviations | 8 | 11 |

| No full dose methotrexate due to elevated liverenzymes or gastrointestinal adverse events | 5 | 5 |

| Reduction prednisolone due to adverse events | 1* | 2† |

| Reduction sulfasalazine due to adverse events | 1 | |

| Switch to leflunomide due to methotrexate intolerance | 1 | |

| Intra-articular injection | 3 | |

| Intramuscular injection | 1 | |

| Minor violations | 13 | 4 |

| No increase to full methotrexate | 9 | 2 |

| Inappropriate increase methotrexate | 2 | |

| Inappropriate step in patient with methotrexate intolerance | 1 | |

| Lower dose sulfasalazine | 1 | |

| Inadequate prednisolone dose | 1‡ | |

| No DMARD temporarily | 1 | |

| Major violations | 6 | 2 |

| No medication for weeks | 2 | |

| Mesalazine instead of sulfasalazine | 1 | |

| Permanent stop of DMARD | 1 | |

| Prednisolone not tapered to 7.5 mg | 1§ | |

| Anti-TNF started at week 13 | 1 | |

| Inappropriate step in patient with methotrexate intolerance | 1 | 1 |

*Prednisolone dose 0 mg/day.

†Prednisolone dose 0 and 5 mg/day.

‡Prednisolone dose 10mg/day.

§Prednisolone dose 15 mg/day.

DMARD, disease-modifying antirheumatic drug; TNF, tumour necrosis factor.

Data excluding patients with any protocol violation (but retaining patients with protocolised treatment deviations) resulted in a difference in ΔDAS44 of 0.42 points in favour of COBRA (95% CI 0.42 to 0.8); adjusted for baseline DAS44: ΔDAS44 is 0.23 points (95% CI −0.1 to 0.57). This difference is still smaller than the previously defined threshold for a clinically relevant difference of 0.5. Analyses with DAS44 CRP: data without patients with a major protocol violation, the difference in ΔDAS44 is 0.08 points (95% CI −0.26 to 0.43); adjusted for baseline DAS44: ΔDAS44 is −0.1 points (95% CI −0.39 to 0.20). Again, per-protocol analyses with a two-sided 90% CI resulted in a CI within the threshold: data without patients with a major protocol violation; adjusted for baseline DAS44: ΔDAS44 is 0.21 points (90% CI −0.06 to 0.47).

Discussion

This study suggests that COBRA-light therapy may be a feasible alternative to COBRA in the first 6 months of treatment. As the CI of the observed difference in ΔDAS44 includes the predefined clinically relevant threshold of 0.5, we are unable to claim non-inferiority fully. However, when analyses were performed with a two-sided 90% CI, or when DAS44 was calculated with CRP, the CI of the ITT and per-protocol analyses are within the predefined threshold of 0.5. The results were consistent across the secondary outcomes, with some trends even favouring COBRA-light (eg, ACR/EULAR remission and ACR50 and ACR70 responses), and only the ESR proved significantly lower in the COBRA arm. In fact, this difference in ESR is the main driver for the observed difference in ΔDAS44 between the groups. In addition, no differences were seen in the safety profile. In other words, COBRA-light therapy seems to be equally effective and safe but has the advantage that it incorporates a lower initial dose of prednisolone and a less complicated treatment schedule. As our study was performed in standard medical practice, with a high inclusion rate of 67% resulting in a patient profile typical for early RA, our results are clinically relevant. Interestingly, more patients declined participation due to the intensity of the study than due to the fear of side effects of the treatment medication, which is in line with earlier research.16

The improvement in disease activity found in this study is comparable with or even better than previous studies of combination therapy for RA.6 9 11 In the COBRA and BeSt trial a mean change in DAS44 of –2.1 resp. –2.3 was found after 6 months treatment with COBRA therapy.6 Both COBRA and COBRA-light resulted in a large number of patients with DAS44 less than 1.6 after 26 weeks of treatment. These proportions are much higher than those found in the original COBRA trial (17% of the patients treated with COBRA), in most part explained by the methotrexate intensification in this study, and seem to be a bit higher than those found in the BeSt trial in which 30–35% of the patients treated with COBRA achieved DAS44 less than 1.6 after 6 months.6 24 Similarly, compared with the original COBRA trial, more patients in this study achieved EULAR good response and ACR70 after 26 weeks. Compared with the previous studies, our patients were enrolled after a short period of symptoms, had a lower DAS44, were less often RF or anti-CCP positive, and, most strikingly, were less often erosive at baseline. Presumably, as a result of advanced insight and altered guidelines, RA patients are seen earlier by the rheumatologist and treatment is initiated earlier than 10 years ago. This study was designed before the results of treat-to-target studies were published, and monitoring more frequent than every 3 months might even improve the results, but the feasibility in routine practice remains to be determined.4 7 8 Compared with other studies a large number of protocol violations were reported, which is due to the use of a specified list during every visit, to the complex drug treatment scheme and to the use of combination therapy of DMARD.

This study reports the clinical data after 26 weeks of treatment. Longer-term clinical effects as well as the effects on radiological progression are still under investigation.

This study has some limitations. The results of open-label trials are more susceptible to bias than blinded studies. To minimise any influence on outcome assessment, these were performed by trained research nurses uninvolved in the routine care. On the other hand, the open-label design more closely mimicked daily practice, which increases its external validity. However, this also resulted in a relatively large proportion of physicians and patients not adhering to the treatment protocol, in most cases leading to suboptimal dosing given the level of disease activity.

Another point is the non-inferiority design. The width of the CI is a function of power, ideally 90% in this type of trial, whereas 80% was the maximum feasible in our setting. The relevance of non-inferiority trials depends on the choice of the non-inferiority margin.25 Based on clinical experience we arbitrarily chose a non-inferiority margin of 0.5 before starting the study. Our point estimate was well below that boundary, but the upper limit of the CI was around the chosen margin. However, 0.53 exceeds the upper limit of 0.50 only minimally, in addition the changes in DAS44 are largely driven by ESR, which was lower after 26 weeks in COBRA than in COBRA-light. Other outcome measures, such as ACR 50/ACR70 remission etc. favour COBRA-light.

Finally, despite the intensive treatment schedules, almost 10% of the patients showed no response, which might be partly due to non-compliance or intolerance for DMARD. A treat-to-target therapy should identify these patients even more quickly and an alternative treatment should be started as soon as possible.

In conclusion, we suggest that COBRA-light therapy is a feasible alternative to COBRA therapy in the first 6 months: both strategies effectively lower disease activity in early, active RA patients and are generally well tolerated. The applicability of COBRA-light will be more fully determined by the 1-year clinical and radiological results.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank all patients as well as all physicians who enrolled patients in this study and all research nurses and students who were involved in patient management. They would also like to thank Dr L Burgemeister and Dr M Gerritsen for their work on an independent committee judging protocol deviations and serious adverse events.

Correction notice: This article has been corrected since it was published Online First. The figures have been updated.

Contributors: Study conception and design: PK, AV, MN, DvS, BD and WL. Acquisition of date: DdU, MtW and HR. Analysis of data, interpretation of data and writing of the manuscript: DdU, MtW and MB. All authors were involved in the study patient care, interpretation of the data and critical revision of the manuscript.

Funding: This research was performed within the framework of project T1-106 of the Dutch Top Institute Pharma, and was additionally funded by an unrestricted grant from Pfizer.

Competing interests: MB: consultancy fees from Roche, Celgene, Horizon, Mundifarma, UCB, BMS and board membership of Novartis. MN: consultancy fees from Roche, Schering-Plough, BMS, UCB, Wyeth, Pfizer and MSD; speaker for Abbott, Roche, Pfizer and BMS; receives research support from Abbott, Roche, Pfizer and UCB. WL: consultancy fees from Abbott, Mercke and Roche. DdU, MtW, PK, AV, HR, DvS, NvD and BD: none declared.

Ethics approval: The medical ethics committee at each participating centre approved the protocol.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Korpela M, Laasonen L, Hannonen P, et al. Retardation of joint damage in patients with early rheumatoid arthritis by initial aggressive treatment with disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs: five-year experience from the FIN-RACo study. Arthritis Rheum 2004;50:2072–81 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lard LR, Visser H, Speyer I, et al. Early versus delayed treatment in patients with recent-onset rheumatoid arthritis: comparison of two cohorts who received different treatment strategies. Am J Med 2001;111:446–51 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mottonen T, Hannonen P, Leirisalo-Repo M, et al. Comparison of combination therapy with single-drug therapy in early rheumatoid arthritis: a randomised trial. FIN-RACo trial group. Lancet 1999;353:1568–73 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bakker MF, Jacobs JW, Welsing PM, et al. Low-dose prednisone inclusion in a methotrexate-based, tight control strategy for early rheumatoid arthritis: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med 2012;156:329–39 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bukhari MA, Wiles NJ, Lunt M, et al. Influence of disease-modifying therapy on radiographic outcome in inflammatory polyarthritis at five years: results from a large observational inception study. Arthritis Rheum 2003;48:46–53 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Goekoop-Ruiterman YP, de Vries-Bouwstra JK, Allaart CF, et al. Clinical and radiographic outcomes of four different treatment strategies in patients with early rheumatoid arthritis (the BeSt study): a randomized, controlled trial. Arthritis Rheum 2005;52:3381–90 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schipper LG, Kievit W, den Broeder AA, et al. Treatment strategies aiming at remission in early rheumatoid arthritis patients: starting with methotrexate monotherapy is cost-effective. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2011;50:1320–30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Smolen JS, Aletaha D, Bijlsma JW, et al. Treating rheumatoid arthritis to target: recommendations of an international task force. Ann Rheum Dis 2010;69:631–7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Boers M, Verhoeven AC, Markusse HM, et al. Randomised comparison of combined step-down prednisolone, methotrexate and sulphasalazine with sulphasalazine alone in early rheumatoid arthritis. Lancet 1997;350:309–18 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Grigor C, Capell H, Stirling A, et al. Effect of a treatment strategy of tight control for rheumatoid arthritis (the TICORA study): a single-blind randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2004;364:263–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.O'Dell JR, Leff R, Paulsen G, et al. Treatment of rheumatoid arthritis with methotrexate and hydroxychloroquine, methotrexate and sulfasalazine, or a combination of the three medications: results of a two-year, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Arthritis Rheum 2002;46:1164–70 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Moreland LW, O'Dell JR, Paulus HE, et al. A randomized comparative effectiveness study of oral triple therapy versus etanercept plus methotrexate in early aggressive rheumatoid arthritis: the treatment of Early Aggressive Rheumatoid Arthritis Trial. Arthritis Rheum 2012;64:2824–35 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Landewe RB, Boers M, Verhoeven AC, et al. COBRA combination therapy in patients with early rheumatoid arthritis: long term structural benefits of a brief intervention. Arthritis Rheum 2002;46:347–56 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.van Tuyl LH, Boers M, Lems WF, et al. Survival, comorbidities and joint damage 11 years after the COBRA combination therapy trial in early rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis 2010;69:807–12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.van Tuyl LH, Plass AM, Lems WF, et al. Why are Dutch rheumatologists reluctant to use the COBRA treatment strategy in early rheumatoid arthritis? Ann Rheum Dis 2007;66:974–6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Arnett FC, Edworthy SM, Bloch DA, et al. The American Rheumatism Association 1987 revised criteria for the classification of rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum 1988;31:315–24 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.den Uyl D, van Raalte DH, Nurmohamed MT, et al. Metabolic effects of high-dose prednisolone treatment in early rheumatoid arthritis: balance between diabetogenic effects and inflammation reduction. Arthritis Rheum 2012;64:639–46 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.den Uyl D, Bultink IE, Lems WF. Glucocorticoid-induced osteoporosis. Clin Exp Rheumatol 2011;29:S93–8 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Prevoo ML, van Gestel AM, van THM, et al. Remission in a prospective study of patients with rheumatoid arthritis. American Rheumatism Association preliminary remission criteria in relation to the disease activity score. Br J Rheumatol 1996;35:1101–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Felson DT, Smolen JS, Wells G, et al. American College of Rheumatology/European League Against Rheumatism provisional definition of remission in rheumatoid arthritis for clinical trials. Arthritis Rheum 2011;63:573–86 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Felson DT, Anderson JJ, Boers M, et al. American College of Rheumatology. Preliminary definition of improvement in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum 1995;38:727–35 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Siegert CE, Vleming LJ, Vandenbroucke JP, et al. Measurement of disability in Dutch rheumatoid arthritis patients. Clin Rheumatol 1984;3:305–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Machin D, Fayers PM. Randomized clinical trials design, practice and reporting. West Sussex, UK; Wiley-Blackwell, 2010: 241–4 [Google Scholar]

- 24.Verhoeven AC, Boers M, van der LS. Responsiveness of the core set, response criteria, and utilities in early rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis 2000;59:966–74 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Piaggio G, Elbourne DR, Altman DG, et al. Reporting of noninferiority and equivalence randomized trials: an extension of the CONSORT statement. JAMA 2006;295:1152–60 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]