Abstract

Objectives

To evaluate prospectively the effect of weight loss on the achievement of minimal disease activity (MDA) in overweight/obese patients with psoriatic arthritis (PsA) starting treatment with tumour necrosis factor α (TNFα) blockers.

Methods

Among subjects with PsA starting treatment with TNFα blockers, 138 overweight/obese patients received a concomitant dietary intervention (69 a hypocaloric diet (HD) and 69 a free-managed diet (FD)). Changes in metabolic variables were measured and a complete clinical rheumatological evaluation was made in all patients at baseline and after a 6-month follow-up to define the achievement of MDA.

Results

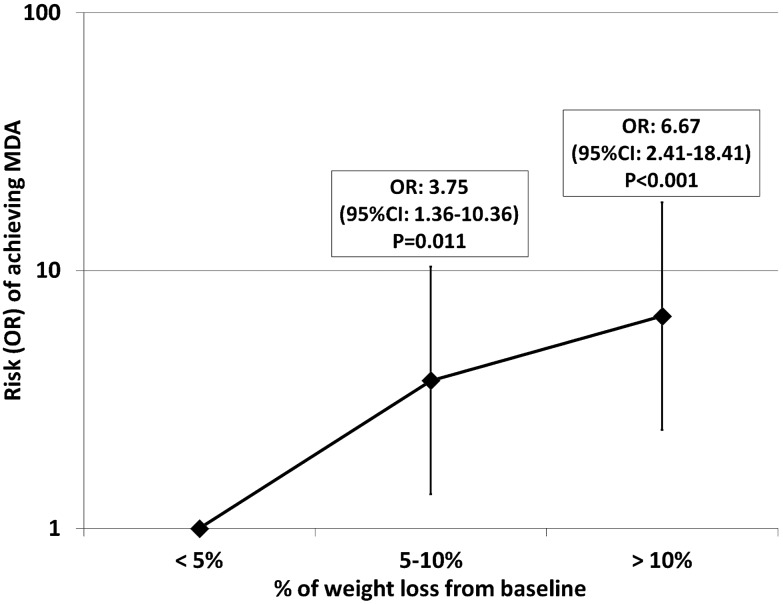

126 subjects completed the study. MDA was more often achieved by HD than by FD subjects (HR=1.85, 95% CI 1.019 to 3.345, p=0.043). A diet was successful (≥5% weight loss) in 74 (58.7%) patients. Regardless of the type of diet, after 6 months of treatment with TNFα blockers, ≥5% of weight loss was a predictor of the achievement of MDA (OR=4.20, 95% CI 1.82 to 9.66, p<0.001). For increasing weight-loss categories (<5%, 5–10%, >10%), MDA was achieved by 23.1%, 44.8% and 59.5%, respectively. A higher rate of MDA achievement was found in subjects with 5–10% (OR=3.75, 95% CI 1.36 to 10.36, p=0.011) and in those with >10% (OR=6.67, 95% CI 2.41 to 18.41, p<0.001) weight loss in comparison with those with <5% weight loss.

Conclusions

Regardless of the type of diet, a successful weight loss (≥5% from baseline values) is associated with a higher rate of achievement of MDA in overweight/obese patients with PsA who start treatment with TNFα blockers.

Keywords: Psoriatic Arthritis, Disease Activity, TNF-alpha

Introduction

Patients with rheumatic diseases, such as psoriatic arthritis (PsA), have an enhanced prevalence of the metabolic syndrome and of its major features.1 In particular, the prevalence of obesity is abnormally high in patients with PsA.2 3 In a large population of 75 395 individuals with psoriasis, obesity has been associated with a high risk of incident PsA.4 Obesity, which leads to changes in levels of cytokines (tumour necrosis factor α (TNFα), interleukin (IL)-6) and ‘adipokines’ (leptin, adiponectin), is associated with a low-grade chronic systemic inflammation.5–7 On the other hand, monocytes, CD4 T lymphocytes and most proinflammatory cytokines (TNFα, IL-1β, IL-6 and IL-18) that play a central role in the pathophysiology of major arthritides,8–10 are also involved in the induction and maintenance of the atherosclerotic process.11–13

Thus, in obese patients with PsA, the obesity-related inflammatory status may acts synergistically with the immunity-related inflammation.14 15 Further supporting this hypothesis, obesity has been recently shown to be a negative predictor of success of a treatment with TNFα blockers in patients with PsA.16

Given that caloric restriction lowers inflammatory cytokines levels in obese subjects,17–19 in this prospective study we evaluated whether the adherence to a hypocaloric diet affects the clinical outcome of patients with PsA starting treatment with TNFα blockers (primary endpoint). In addition, we evaluated the relationship between the extent of weight loss and clinical response to TNFα blockers.

Methods

During a 30-month period (January 2009–July 2011), all patients with a diagnosis of PsA (CASPAR criteria),20 for whom treatment with traditional disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs) had failed and who were referred to the psoriatic arthritis clinic of the Federico II University of Naples to start treatment with TNFα blockers, were screened for inclusion in this study. All patients were classified into clinical subsets (axial, peripheral, axial+peripheral, mutilans) according to standard criteria.21 22

Exclusion criteria were lack of written informed consent; age <18 years, previous treatment with TNFα blockers, current treatment with corticosteroids, history of arterial or venous thrombosis, malignancy, haematological/oncological diseases, autoimmune diseases other than PsA, unstable medical conditions, ongoing pregnancy.

After approval of the local ethics committee and after receipt of written informed consent, 138 overweight/obese patients with PsA were included in this study. None had received any dietary advice before study entry. Information about age, gender, height, weight, disease duration, disease activity, vascular risk factors and previous and/or current treatments was collected from all patients according to standard procedures.23

Overweight was defined as a body mass index (BMI) between 25 and 30; obesity was defined as a BMI >30 and/or a waist circumference >102 cm for men and of 88 cm for women.16 24 The presence of a treatment for hypertension, hyperlipidaemia or impaired fasting glucose was recorded. When needed, appropriate adjustments for such treatments were made before study entry.

At the time of enrolment, a randomly generated number sequence was used to randomise patients to receive a hypocaloric diet (HD group) or a free self-managed diet (FD group).

HD was designed to produce a caloric restriction of about 30% of total energy requirements.17 It included the restriction of calorie intake to <1500 kcal/day, restriction of fat intake to 30–35% of total daily energy uptake (reservation of 10% for monounsaturated fatty acids, eg, olive oil), avoidance of trans fats, high-fibre uptake (to 30 g/day) and the avoidance of liquid monosaccharides and disaccharides. In the FD arm, although there was no quantitative food restriction, all patients were advised to eat no more than two pieces of fresh fruit daily and to use no more than two spoons daily of olive oil; to avoid saturated fats; to increase the daily use of vegetables and to eat more fish (at least 1 portion/week).

After baseline evaluation (T0), rheumatological outcomes of patients were evaluated monthly and nutritional and cardiometabolic status every other month, with a total follow-up of 6 months (T1).

Nutritional data, recorded in 7-day nutritional diaries,25 were evaluated every other month to assess mean calories intakes and adherence to the nutritional intervention. Diet schedule and nutritional data were managed by a physician (RL) trained in human nutrition and blinded to the rheumatological disease activity. Every other month hypertension, hypercholesterolaemia, hypertriglyceridaemia, impaired fasting glucose, height, weight, BMI and waist circumference were evaluated in all patients. According to the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence guidelines, dietary intervention was defined as ‘successful’ if the original weight was reduced by 5–10% within 6 months.26 Given the recognised intraindividual variability in triglycerides (20%) and in total cholesterol (10%) levels (owing to analytical variation, physical activity and seasonal variation), only changes above these cut-off points were considered significant.27 Significant changes in fasting glucose were those >10%,28 and reductions >20 mm Hg for systolic and >10 mm Hg for diastolic arterial blood pressure were considered significant.29

During the 6-month follow-up, all patients with PsA underwent a monthly rheumatological evaluation including tender joint count (TJC), swollen (SJC) joint count, tender entheseal count, Psoriasis Area Severity Index (PASI), Health Assessment Questionnaire (HAQ), Visual Analogue Scale for pain (VAS), patient global disease activity VAS score, erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) and C-reactive protein (CRP). Patients were classified as having achieved minimal disease activity (MDA) only when fulfilling five of the following seven outcome measures at T1: TJC ≤1; SJC ≤1; PASI ≤1 or body surface area ≤3; VAS for pain ≤15; patient global disease activity VAS score of ≤20; HAQ ≤0.5 and tender entheseal points ≤1.30

Rheumatological assessments were performed by a trained staff (RP and SI) blinded to the nutritional schedule of each subject. No physiotherapy or rehabilitation was carried out in enrolled patients throughout the study period.

Statistical analysis

Data were analysed with the SPSS 16 system (SPSS Inc, Chicago, Illinois, USA). Continuous data were expressed as mean±SD; categorical variables were expressed as a percentage. The t test and the χ2 test were performed to compare continuous and categorical data, respectively. When the minimum expected value was <5, the Fisher exact test was used. The study population was stratified into categories according to percentage changes (Δ%) of weight loss (<5%, 5–10%, >10%). To evaluate the cumulative hazard of achieving MDA as related to type of diet, a Cox regression model (stepwise method) was adopted. In a post hoc analysis, the effect of body weight changes on achievement of MDA was evaluated by a logistic regression model (stepwise method). Both in Cox analysis and in the logistic regression, the achieving of MDA was the dependent variable; type of diet, weight loss, compliance with diet, TJC, SJC, tender entheseal count, PASI, HAQ, VAS for pain, patient global VAS, ESR, CRP, gender, age, disease duration, disease subset, concomitant treatment with methotrexate (MTX), smoking habits, diabetes, hypercholesterolaemia, hypertriglyceridaemia, hypertension (and their changes during follow-up) were independent variables. A multicollinearity effect in multivariable regression models was excluded by a stepwise approach, variables being included for p<0.05, excluded for p>0.1. A tolerance test excluded models in which the sum of the values exceeded the sum of the variances for all variables. All the results are given as two-tailed values with statistical significance for p values <0.05. For a study with a >1.55 minimal predefined HR between the two diet protocols for the achievement of MDA, and a 1 : 1 ratio between subjects in the two study arms, at least 61 subjects for each diet group are needed to obtain a >80% power with a 5% α error.

Results

Of the 138 subjects enrolled, 12 were excluded because of missing nutritional diary data (three HD subjects); premature (before 6 months) withdrawing of TNFα blocker treatment (two HD and one FD subject) and missing follow-up visit (one HD and five FD subjects). Baseline clinical and demographic data of the 126 subjects who completed the study are reported in table 1. Of these, 36.2% were taking statins, 24.3% ω-3 fatty acids, 19.6% oral hypoglycaemic agents and 18.1% antihypertensive drugs. All 126 patients had active disease at the time of enrolment. The type of TNFα blocker drug used was as follows: 59 (46.8%) etanercept (50 mg/week); 33 (26.2%) adalimumab (40 mg every other week) and 34 (27.0%) infliximab (3 mg/kg at weeks 0, 2 and 6 and every 8 weeks thereafter). A concomitant treatment with MTX (10–15 mg/week) was found in 37 (29.4%) patients. With the exception of infliximab, the dosage of which was modified according to body weight changes, no variation in the dosing/scheduling of other drugs was made during the observation period. No significant changes occurred in the treatment schedules of antihypertensive drugs, statins, and intake of ω-3 fatty acids or hypoglycaemic agents.

Table 1.

Clinical and demographic characteristics of the study population

| Variable | Whole sample (n=126) |

HD (n=63) |

FD (n=63) |

p Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 45.15±11.52 | 46.83±10.40 | 43.48±12.40 | 0.103 |

| Male gender | 46 (36.5) | 23 (36.5) | 23 (36.5) | 1.000 |

| Clinical subset | ||||

| Axial+peripheral | 63 (50.0) | 35 (55.6) | 28 (44.4) | 0.285 |

| Peripheral | 42 (33.3) | 19 (30.2) | 23 (36.5) | 0.571 |

| Axial | 21 (16.7) | 9 (14.3) | 12 (19.0) | 0.633 |

| Mutilans | – | – | – | – |

| Concomitant MTX | 37 (29.4) | 16 (25.4) | 21 (33.3) | 0.434 |

| Disease duration (years) | 4.87±2.94 | 4.63±2.68 | 5.10±3.19 | 0.383 |

| ESR (mm/h) | 20.65±16.08 (range 6–70) | 20.38±13.49 (range 6–65) | 20.93±18.41 (range 9–70) | 0.847 |

| CRP (mg/l) | 6.03±7.45 (range 5–18) | 5.58±5.24 (range 5–16) | 6.48±9.17 (range 5–18) | 0.501 |

| SJC | 3.08±4.46 (range 3–22) | 3.84±5.76 (range 3–22) | 2.42±2.77 (range 4–18) | 0.101 |

| TJC | 14.50±10.47 (range 8–40) | 16.38±9.91 (range 8–40) | 13.02±10.74 (range 12–39) | 0.090 |

| PASI | 0.77±0.89 (range 0.5–3.5) | 0.68±0.76 (range 0.5–3.0) | 0.84±0.99 (range 0.5–3.5) | 0.353 |

| HAQ | 1.87±0.90 (range 0.5–3) | 2.02±0.75 (range 0.5–3) | 1.75±1.00 (range 0.5–2.8) | 0.131 |

| VAS | 72.3±19.5 (range 45–100) | 74.3±19.1 (range 45–100) | 72.5±22.7 (range 48–100) | 0.658 |

| Patient global VAS | 73.3±21.1 (range 50–100) | 72.7±20.0 (range 50–100) | 74.0±23.1 (range 51–100) | 0.696 |

| Tender entheseal count | 8.93±2.26 (range 4–13) | 8.72±3.87 (range 4–13) | 9.15±3.44 (range 5–13) | 0.426 |

| Hypercholesterolaemia | 47 (37.3) | 28 (44.4) | 19 (30.2) | 0.140 |

| Hypertriglyceridaemia | 32 (25.4) | 20 (31.7) | 12 (19.0) | 0.151 |

| Impaired fasting glucose | 29 (23.0) | 14 (22.2) | 15 (23.8) | 1.000 |

| Hypertension | 26 (20.6) | 16 (25.4) | 10 (15.9) | 0.271 |

| Abdominal obesity | 126 (100) | 63 (100) | 63 (100) | 1.000 |

| Body weight (kg) | 86.12±6.87 | 84.96±7.19 | 87.28±6.38 | 0.058 |

| Body mass index | 31.24±2.28 | 31.32±2.00 | 31.16±2.54 | 0.703 |

Results are shown as mean±SD or number (%).

CRP, C-reactive protein; ESR, erythrocyte sedimentation rate; FD, free-diet group; HAQ, Health Assessment Questionnaire; HD, hypocaloric diet group; MTX, methotrexate; PASI, Psoriasis Area Severity Index; SJC, swollen joint count; TJC, tender joint count; VAS, Visual Analogue Scale for pain.

6-Month follow-up

During the follow-up, a successful diet (≥5% weight loss) was achieved by 74 (58.7%) subjects, the remaining 52 subjects experiencing a <5% weight loss (n=41) or ≈2 kg weight gain (n=11). In more detail, a 5–10% weight reduction was achieved by 48 (38.1%) patients and a ≥10% weight loss was achieved by 26 patients (20.6%) patients.

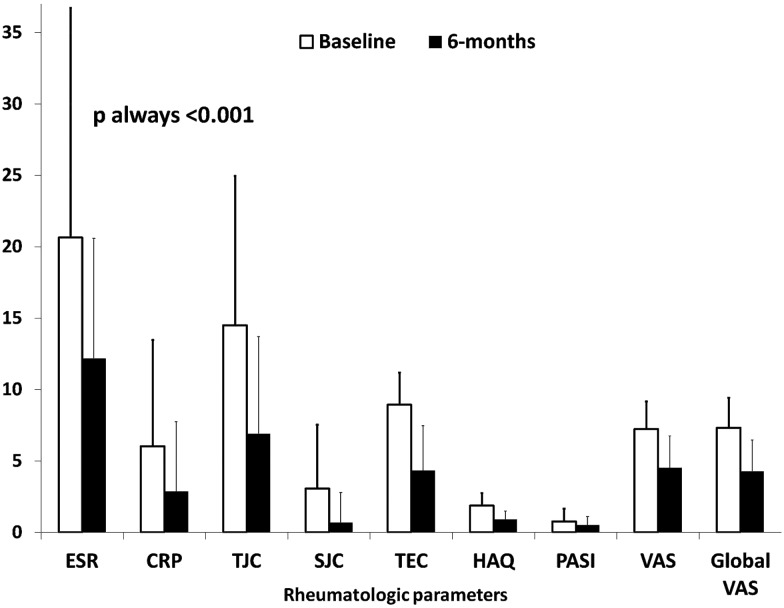

In parallel, significant changes (see ‘Methods’ section) in plasma cholesterol, triglycerides, fasting glucose and arterial blood pressure were found in 33 (26.2%), 34 (27.0%), 27 (21.4%) and 18 (14.3%) patients, respectively. Compared with baseline, TJC, SJC, tender entheseal count, PASI, HAQ, VAS, patient global VAS, CRP and ESR changed significantly during the 6 months’ follow-up (figure 1). Overall, 49 (38.9%) patients with PsA achieved the MDA. Stratifying for TNFα blocker drug, MDA was achieved by 26/59 (44.1%) patients receiving etanercept, by 11/33 (33.3%) of those receiving adalimumab and by 12/34 (35.3%) of those receiving infliximab (p for trend 0.527). Concomitant treatment with MTX was present in 10 (20.4%) of patients achieving MDA and in 27 (35.1%) of those that did not (p=0.108).

Figure 1.

Changes in rheumatological clinical outcome measures from baseline (T0) to the 6-month (T1) visit. p Values are for paired sample t test; CRP, C-reactive protein; ESR, erythrocyte sedimentation rate; HAQ, Health Assessment Questionnaire; PASI, Psoriasis Area Severity Index; SJC, swollen joint count; TEC, tender entheseal count; TJC, tender joint count; VAS, Visual Analogue Scale for pain. VAS and global VAS are reported in centimetres in this figure.

Effects of the dietary intervention

During the follow-up, periodic evaluations of the nutritional diaries showed that a mean caloric restriction ≥30% of total energy requirements was achieved by 41 (65.1%) HD subjects and by 26 (41.3%) FD subjects. Of the 74 patients experiencing a ≥5% weight loss, 49 belonged to the HD and 25 to the FD group (p<0.001). After adjusting for clinical and demographic data, HD subjects were more likely to achieve a ≥5% weight loss than FD subjects (HR=3.23, 95% CI 1.93 to 5.39, p<0.001).

Among those with significant changes in plasma cholesterol, triglycerides, fasting glucose and arterial blood pressure only 6.1%, 23.6%, 14.8%, 16.7%, respectively, belonged to the FD group. On the other hand, by evaluating changes in rheumatological outcome measures, it was found that, compared with those on a FD, HD subjects showed a higher reduction in ESR (14.9±18.0 vs 2.04±15.5, p<0.001) and in VAS (4.46±3.06 vs 2.77±2.65, p=0.004). Changes in all the other outcome measures did not significantly differ between HD and FD subjects (p always >0.05).

Overall, MDA was achieved by 27 (42.9%) HD and 22 (34.9%) FD subjects (HR=1.85, 95% CI 1.019 to 3.345, p=0.043)

Effects of weight loss

Compared with those with <5% weight loss, patients with ≥5% weight loss exhibited a higher mean reduction in CRP (5.01±9.5 vs 1.37±7.48, p=0.023), ESR (12.25±18.22 vs 3.09±16.2, p=0.004), VAS (4.00±2.90 vs 1.97±2.42, p=0.018), global VAS (4.68±2.92 vs 2.56±1.94, p<0.001) and HAQ (1.29±0.79 vs 0.53±0.67, p=0.004).

Stratifying results for categories of weight loss, subjects with >10% weight loss exhibited a higher reduction in VAS (5.06±2.64 vs 1.97±2.42, p<0.001), in global VAS (4.26±2.02 vs 2.56±1.94, p=0.008) and in ESR (14.45±20.14 vs 3.09±16.2, p<0.001) than those reporting <5% weight loss. In contrast, those experiencing a 5–10% weight loss, showed a higher reduction in VAS (4.05±3.04 vs 1.97±2.42, p=0.005) and ESR (11.51±14.86 vs 3.09±16.2, p=0.004) as compared with subjects with <5% weight loss.

MDA was achieved by 50.0% of patients with a successful diet (≥5% weight loss) and by 23.1% of those without (OR=4.20, 95% CI 1.82 to 9.66, p<0.001).

Interestingly, for increasing categories of weight loss (<5%, 5–10%, >10%), MDA was achieved by 23.1%, 44.8% and 59.5%, respectively. Overall, MDA achievement was more frequent in subjects with 5–10% or with >10% weight loss than in those with <5% weight loss (figure 2).

Figure 2.

MDA achievement according to categories of weight loss changes during the 6 months’ follow-up. MDA, minimal disease activity.

After stratifying for weight loss categories, HD was no longer a predictor of achieving MDA (OR=1.57, 95% CI 0.895 to 2.774, p=0.115).

Of interest, a ≥5% weight loss was a significant predictor of achieving MDA in subjects with the axial subset ( OR=8.16, 95% CI 1.53 to 43.39, p=0.014) and in those with the axial+peripheral subset (OR=4.16, 95% CI 1.35 to 12.88, p=0.013), but not in those with the peripheral subset (OR=1.94, 95% CI 0.25 to 15.1, p=0.525).

Discussion

Among clinical and laboratory predictors of the response to TNFα blockers,31 32 data on ‘metabolic’ variables are limited. The main finding of this prospective study is that regardless of the type of diet a ≥5% weight loss is the major and independent predictor of MDA achievement in overweight/obese patients with PsA starting treatment with TNFα blockers.

Although poorly studied in patients with PsA, the impact of weight loss on inflammatory markers has been widely evaluated in ‘metabolic’ populations. Cytokines and adipokines are implicated in the aetiology of a proinflammatory status as much as in insulin resistance, type 2 diabetes and atherosclerosis.17 A caloric restriction lowers levels of several inflammatory (ie, CRP and TNFα) and metabolic (ie, cholesterol, triglycerides and body weight) markers.17 Confirming and extending these data, we found that, compared with those without a successful diet, patients with ≥5% weight loss exhibited a higher reduction in some rheumatological outcome measures (ESR, CRP, VAS, global VAS and HAQ). Overall, these data support the possibility that, by reducing inflammation, weight loss may be associated with an improvement in the response to TNFα blockers.

Weight loss may affect the achievement of MDA also by changing the pharmacodynamic properties (ie, distribution volume) of TNFα blockers. In addition, at variance with the other TNFα blockers used, infliximab needs weight-adjusted doses. The lack of a meticulous dose adjustment might affect the response to this TNFα blocker. However, despite some inherent limitations (drug presentation in 100 mg vials), special attention was paid to adjustment of infliximab dosages for body weight during the study period. Overall, the finding that no difference in achieving MDA was found among different TNFα blockers, suggests that weight loss has an independent effect on its achievement. However, this should be further verified in ad hoc studies.

Given the ability of HD to affect several inflammatory markers,17 in this study, we tested its impact on the achievement of MDA in patients with PsA who started treatment with TNFα blockers. In parallel to a more significant weight loss, a higher rate of MDA achievement was found in HD than FD subjects. Of interest, when the category of weight loss was included in the multivariate analysis, HD was no longer a significant predictor of MDA. Whether this finding suggests that regardless of type of diet the weight loss itself helps to achieve MDA is unknown and deserves to be further analysed.33 Although the sample size was calculated to evaluate the different effect of HD and FD on MDA achievement, a >80% power (with <5% α error) was found for results of the post hoc analysis.

Chronic inflammation and vascular risk factors act synergistically, leading to an increased cardiovascular (CV) risk in rheumatic patients.2 The European League Against Rheumatism (EULAR) suggests a periodic CV risk assessment in rheumatological settings, including disease activity as an independent risk factor.34 In turn, major markers of atherosclerosis (carotid plaques; hepatic steatosis), besides globally assessing the damage due to cardiometabolic and/or inflammatory determinants,35 36 seem to help to identify patients at high risk of not achieving MDA.22

Accordingly, besides CV risk profile improvement, weight loss seems to render patients more likely to achieve MDA. These data have to be analysed in the framework of the growing research field aimed at identifying predictors of a successful treatment with TNFα blockers.32 These drugs are expensive37 and have serious side effects,38 and thus newer predictors of success would be helpful in identifying patients with the highest efficacy/safety ratios in whom their use would be beneficial.

Some limitations of this study need to be discussed. About 20% of the patients of this study were receiving chronic treatment with oral hypoglycaemic agents. Although glucagon-like peptide-1 agonists, metformin and sulfonylurea are known to modify body weight,39 patients had been receiving hypoglycaemic treatment for at least 1 year before study entry. This makes it unlikely that weight loss seen during the study period was due to the use of such drugs in our patients.

The prevalence of axial involvement is high in our sample. The presence of an axial subset, which has a high rate of refractoriness to DMARDs, has been recognised as a major criterion for starting treatment with TNFα blockers.40 Thus, the selection criteria of our study population might have led to such a high prevalence. PASI scores seem to be rather low in our sample. At the time of enrolment, before starting TNFα blockers, all study patients were receiving treatment with traditional DMARDs, which might have affected baseline PASI scores.

In this study, MDA was defined according to Outcome Measures in Rheumatology Clinical Trials (OMERACT) criteria,41 whose efficacy in providing outcome measures for clinical trials has been acknowledged.30 Although other criteria may be used to define a good clinical response, some of these (28-joint count Disease Activity Score) do not assess distal interphalangeal joints and are not recommended for assessing disease activity in patients with PsA.42 In the absence of an established ‘gold standard’, and in view of its feasibility in daily clinical practice, we chose to use the reported definition of MDA in this study. We also evaluated the impact of diet and of weight loss on each rheumatological outcome measure in order to identify variables most extensively changed by nutritional intervention. In conclusion, this study shows that a successful diet (≥5% weight loss) is associated with a higher achievement of MDA in overweight/obese patients with PsA who start treatment with TNFα blockers.

Acknowledgments

All members of the Cardiovascular Risk in Rheumatic Diseases Study Group were involved in literature search, organisation of the work and editing of the manuscript. All authors revised and approved this version of this manuscript and approved the mention of their names in the article.

Footnotes

Collaborators: Cardiovascular Risk in Rheumatic Diseases Study Group (CaRRDs): Matteo Nicola Dario Di Minno, Anna Russolillo, Alessandro Di Minno, Giovanni Tarantino, Giovanni Di Minno (Department of Clinical Medicine and Surgery, Regional Reference Centre for Coagulation Disorders, Federico II University, Naples, Italy); Rosario Peluso, Raffaele Scarpa (Department of Clinical Medicine and Surgery, Rheumatology Research Unit, Psoriatic Arthritis Clinic, Federico II University, Naples, Italy); Paolo Osvaldo Rubba (Department of Clinical Medicine and Surgery, Atherosclerosis Prevention and Vascular Medicine Unit, Federico II University, Naples, Italy); Salvatore Iervolino (Reumatology and Rehabilitation Research Unit, ‘Salvatore Maugeri’ Foundation, Scientific Institute of Telese Terme (BN), Italy).

Contributors: MNDDM conceived and designed the study, performed the statistical analysis interpreted the results and drafted the manuscript; RP, SI and AR acquired clinical data and drafted the manuscript; RL designed the nutritional intervention, acquired metabolic data and drafted the manuscript; RS interpreted the results and performed critical revision of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Competing interests: None.

Ethics approval: Federico II University local ethics committee.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Contributor Information

Collaborators: Matteo Nicola Dario Di Minno, Anna Russolillo, Alessandro Di Minno, Giovanni Tarantino, Giovanni Di Minno, Rosario Peluso, Raffaele Scarpa, Paolo Osvaldo Rubba, and Salvatore Iervolino

References

- 1.Tyrrell PN, Beyene J, Feldman BM, et al. Rheumatic disease and carotid intima-media thickness: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2010;30:1014–26 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Di Minno MND, Iervolino S, Lupoli R, et al. Cardiovascular risk in rheumatic patients: the link between inflammation and atherosclerosis. Semin Thromb Hemost 2012;38:497–505 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jamnitski A, Symmons D, Peters MJ, et al. Cardiovascular comorbidities in patients with psoriatic arthritis: a systematic review. Ann Rheum Dis 2013;72:211–16 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Love TJ, Zhu Y, Zhang Y, et al. Obesity and the risk of psoriatic arthritis: a population-based study. Ann Rheum Dis 2012;71:1273–7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Peters MJ, van der Horst-Bruinsma IE, Dijkmans BA, et al. Cardiovascular risk profile of patients with spondylarthropathies, particularly ankylosing spondylitis and psoriatic arthritis. Semin Arthritis Rheum 2004;34:585–92 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ahima RS, Flier JS. Adipose tissue as an endocrine organ. Trends Endocrinol Metab 2000;11:327–32 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yudkin JS, Stehouwer CD, Emeis JJ, et al. C-reactive protein in healthy subjects: associations with obesity, insulin resistance, and endothelial dysfunction: a potential role for cytokines originating from adipose tissue? Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 1999;19:972–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sattar N, McCarey DW, Capell H, et al. Explaining how “high-grade” systemic inflammation accelerates vascular risk in rheumatoid arthritis. Circulation 2003;108:2957–63 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.del Rincon ID, Williams K, Stern MP, et al. High incidence of cardiovascular events in a rheumatoid arthritis cohort not explained by traditional cardiac risk factors. Arthritis Rheum 2001;44:2737–45 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.van Kuijk AW, Reinders-Blankert P, Smeets TJ, et al. Detailed analysis of the cell infiltrate and the expression of mediators of synovial inflammation and joint destruction in the synovium of patients with psoriatic arthritis: implications for treatment. Ann Rheum Dis 2006;65:1551–7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dixon WG, Symmons DP. What effects might anti-TNF-alpha treatment be expected to have on cardiovascular morbidity and mortality in rheumatoid arthritis? A review of the role of TNF-alpha in cardiovascular pathophysiology. Ann Rheum Dis 2007;66:1132–6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Popa C, van den Hoogen FH, Radstake TR, et al. Modulation of lipoprotein plasma concentrations during long-term anti-TNF therapy in patients with active rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis 2007;66:1503–7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Libby P. Changing concepts of atherogenesis. J Intern Med 2000;247:349–58 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Russolillo A, Iervolino S, Peluso R, et al. Obesity and psoriatic arthritis: from pathogenesis to clinical outcome and management. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2013;52:62–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rondinone CM. Adipocyte-derived hormones, cytokines, and mediators. Endocrine 2006;29:81–90 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Di Minno MN, Peluso R, Iervolino S, et al. Obesity and the prediction of minimal disease activity. A prospective study in Psoriatic Arthritis. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2013;65:141–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hermsdorff HH, Zulet MÁ, Abete I, et al. Discriminated benefits of a Mediterranean dietary pattern within a hypocaloric diet program on plasma RBP4 concentrations and other inflammatory markers in obese subjects. Endocrine 2009;36:445–51 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hermsdorff HHM, Zulet MA, Bressan J, et al. Impact of caloric restriction and Mediterranean food-based diets on inflammation accompanying obesity and metabolic syndrome features. Obe Metab 2009;5:69–77 [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nicklas BJ, Ambrosius W, Messier SP, et al. Diet-induced weight loss, exercise, and chronic inflammation in older, obese adults: a randomized controlled clinical trial. Am J Clin Nutr 2004;79:544–51 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Taylor W, Gladman D, Helliwell P, et al. Classification criteria for psoriatic arthritis: development of new criteria from a large international study. Arthritis Rheum 2006;54:2665–73 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Moll JM, Wright V. Psoriatic arthritis. Semin Arthritis Rheum 1973;3:55–78 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Di Minno MN, Peluso R, Iervolino S, et al. Hepatic steatosis, carotid plaques and achieving MDA in psoriatic arthritis patients starting TNF-α blockers treatment: A prospective study. Arthritis Res Ther 2012;14:R211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Di Minno MN, Iervolino S, Peluso R, et al. Carotid intima-media thickness in psoriatic arthritis: differences between tumor necrosis factor-α blockers and traditional disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs. Artherioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2011;31:705–12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Di Minno MN, Tufano A, Guida A, et al. Abnormally high prevalence of major components of the metabolic syndrome in subjects with early-onset idiopathic venous thromboembolism. Thromb Res 2011;127:193–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bingham S, Welch A, McTaggart A, et al. Nutritional methods in the European Prospective Investigation of Cancer in Norfolk. Public Health Nutr 2001;4:847–58 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.National Collaborating Centre for Primary Care. Obesity: the prevention, identification, assessment and management of overweight and obesity in adults and children. London, UK: National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence, 2006. http://www.nice.org.uk/nicemedia/pdf/CG43NICEGuideline.pdf (accessed 5 Sept 2012). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Reiner Z, Catapano AL, De Backer G, et al. ESC/EAS Guidelines for the management of dyslipidaemias: the Task Force for the management of dyslipidaemias of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and the European Atherosclerosis Society (EAS). Eur Heart J 2011;32:1769–818 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rydén L, Standl E, Bartnik M, et al. Guidelines on diabetes, pre-diabetes, and cardiovascular diseases: executive summary. The Task Force on Diabetes and Cardiovascular Diseases of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and of the European Association for the Study of Diabetes (EASD). Eur Heart J 2007;28:88–136 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mancia G, De Backer G, Dominiczak A, et al. 2007 Guidelines for the management of arterial hypertension: The Task Force for the Management of Arterial Hypertension of the European Society of Hypertension (ESH) and of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Eur Heart J 2007;28:1462–536 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Coates LC, Helliwell PS. Validation of minimal disease activity criteria for psoriatic arthritis using interventional trial data. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2010;62:965–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Coates LC, Cook R, Lee K, et al. Frequency, predictors, and prognosis of sustained minimal disease activity in an observational psoriatic arthritis cohort. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2010;62:970–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Iervolino S, Di Minno MN, Peluso R, et al. Predictors of early minimal disease activity in patients with psoriatic arthritis treated with tumor necrosis factor-α blockers. J Rheumatol 2012;39:568–73 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gladman DD, Callen JP. Early-onset obesity and risk for psoriatic arthritis. JAMA 2010;304:787–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Peters MJ, Symmons DP, McCarey D, et al. EULAR evidence-based recommendations for cardiovascular risk management in patients with rheumatoid arthritis and other forms of inflammatory arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis 2010;69:325–31 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Di Minno MND, Iervolino S, Peluso R, et al. TNF-α blockers and carotid intima-media thickness. An emerging issue in the treatment of psoriatic arthritis. Intern Emerg Med 2012;7(Suppl 2):S97–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Di Minno MND, Iervolino S, Peluso R, et al. Hepatic steatosis and disease activity in subjects with Psoriatic arthritis on TNF-α blockers. J Rheumatol 2012;39:1042–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Olivieri I, Mantovani LG, D'Angelo S, et al. Psoriatic arthritis: pharmacoeconomic considerations. Curr Rheumatol Rep 2009;11:263–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Peluso R, Cafaro G, Di Minno A, et al. Side effects of TNF-α blockers in patients with psoriatic arthritis: evidences from literature studies. Clin Rheumatol Published Online First: 16 April 2013. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10067-013-2252-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gross JL, Kramer CK, Leitão CB, et al. Effect of antihyperglycemic agents added to metformin and a sulfonylurea on glycemic control and weight gain in type 2 diabetes: a network meta-analysis. Ann Intern Med 2011;154:672–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.van der Heijde D, Sieper J, Maksymowych WP, et al. 2010 Update of the international ASAS recommendations for the use of anti-TNF agents in patients with axial spondyloarthritis. Ann Rheum Dis 2011;70:905–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wells GA, Boers M, Shea B, et al. Minimal disease activity for rheumatoid arthritis: a preliminary definition. J Rheumatol 2005;32:2016–24 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mease PJ, Antoni CE, Gladman DD, et al. Psoriatic arthritis assessment tools in clinical trials. Ann Rheum Dis 2005;64(Suppl 2):ii49–54 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]