Abstract

Background

In a prospective observational study, we investigated whether patients with active systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) had higher indices of endothelial damage and dysfunction than healthy controls and whether improved disease control was associated with improvement in these indices.

Methods

Twenty-seven patients with active SLE (four or more American College of Rheumatology (ACR) criteria) and 22 age-matched controls were assessed. Endothelial microparticles (EMPs; CD31+/annexin V+/CD42b−) were quantified using flow cytometry. Brachial artery flow-mediated dilatation (FMD) was measured using automated edge-tracking software. Twenty-two patients had a second assessment at a median (IQR) of 20 (16, 22) weeks after initiating new immunosuppressive therapy.

Results

SLE patients had a median (IQR) baseline global British Isles Lupus Assessment Group Disease Activity Index (BILAG-2004) score of 14 (12, 22). CD31+/annexin V+/CD42b− EMPs were higher (157 548/ml (59 906, 272 643) vs 41 025(30 179, 98 082); p=0.003) and endothelial-dependent FMD was lower (1.63% (−1.22, 5.32) vs 5.40% (3.02, 8.57); p=0.05) in SLE patients than controls. CD31+/annexin V+/CD42b− EMPs correlated inversely with FMD (%) (r2 −0.40; p=0.006). At follow-up, the median (IQR) change in global BILAG-2004 score was −11 (−18, −3). CD31+/annexin V+/CD42b− EMP levels were reduced (166 982/ml (59 906, 278 775 vs 55 655(29 475, 188 659; p=0.02) and FMD had improved (0.33% (−2.31, 4.1) vs 3.19% (0.98, 5.09); p=0.1) at the second visit.

Conclusions

Active SLE is associated with evidence of increased endothelial damage and endothelial dysfunction, which improved with suppression of inflammation. Better control of active inflammatory disease may contribute to improved cardiovascular risk in patients with SLE.

Keywords: Systemic Lupus Erythematosus, Cardiovascular Disease, Disease Activity

Introduction

Women with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) have a greater than fivefold increased risk of coronary heart disease (CHD) events and, notably, there is a 50-fold increased risk in younger patients.1 SLE patients also have an increased burden of subclinical atherosclerosis, as measured by coronary calcium score, carotid plaque, and arterial stiffness.2–5 Although classic Framingham risk factors are more prevalent in SLE,6 they do not fully explain this excess CHD risk,7 and SLE is therefore considered an independent risk factor for cardiovascular disease (CVD).

The increased CVD risk is multifactorial,8 and the vascular endothelium may be a key interface between inflammation and atherogenesis in SLE.9 Endothelial dysfunction represents the earliest clinically detectable stage in the development of atherosclerosis, and reduced flow-mediated dilatation (FMD) of conduit arteries is associated with traditional CHD risk factors10–12 and prevalent CVD13 and predicts future coronary events.14 We and others have demonstrated impaired FMD in patients with SLE, and, although FMD improves with statins15 and omega-3 fatty acids,16 the contribution of inflammation to endothelial dysfunction has yet to be assessed in an SLE population.

Endothelial microparticles (EMPs) are membrane-bound subcellular microparticles (MPs) produced by endothelial cells in response to a variety of triggers, and may act as a biomarker for endothelial damage. EMPs are increased in acute coronary syndromes17 18 and patients with traditional CHD risk factors,19 20 and higher EMPs predict adverse outcomes in patients with stable, prevalent CHD.21 EMPs correlate with other measures of vascular damage22 23 and may reflect disease activity in childhood vasculitis,24 contribute to the prothrombotic environment in antiphospholipid syndrome25 and contribute to the immunopathogenesis of SLE.26 To date, there are no studies examining whether EMPs act as biomarkers of endothelial damage and cardiovascular risk in SLE.

In the present study, we investigated whether active SLE is associated with increased endothelial damage (EMPs) and dysfunction (FMD), compared with age- and gender-matched controls. We subsequently examined the hypothesis that improvements in inflammatory disease activity would result in improvements in these measures in a prospective longitudinal observational study, and assessed the relationship between endothelial damage, endothelial dysfunction and disease activity.

Methods

Patients

Patients with SLE (four or more 1997 American College of Rheumatology (ACR) revised criteria27) were recruited from The Kellgren Centre for Rheumatology, Central Manchester NHS Foundation Trust (CMFT) and East Lancashire Hospitals NHS Trust. Patients were included if they had active SLE sufficient for their treating physician to initiate a change in their immunosuppressive therapy. Specifically, we included patients starting treatment with any of azathioprine, mycophenolate mofetil, cyclophosphamide or rituximab. Healthy, age-matched controls were recruited from friends of patients or from staff at the University of Manchester and CMFT. We excluded subjects with a recent acute infection (≤1 month), recent cardiovascular event (≤3 months), any chronic infection, pregnant/lactating patients, and patients with chronic kidney disease (estimated glomerular filtration rate ≤20 ml/min). All subjects gave written informed consent, and ethics approval was obtained from Oldham Research Ethics Committee.

Clinical and laboratory assessment

Patients with SLE were assessed before the change in therapy and again approximately 4–5 months later. The referring rheumatologist dictated all changes in therapy. Control subjects were assessed once. Subjects fasted for 12 h before the study, and were asked to abstain from smoking tobacco on the morning of the study. All subjects underwent a full history and physical examination at each visit, with CVD history and drug exposures documented. Patients underwent detailed assessment of their current and past SLE features and therapeutic history. Two composite scores of disease activity were recorded at each visit: the British Isles Lupus Assessment Group Disease Activity Index (BILAG-2004)28 and the SLE Disease Activity Index 2000 (SLEDAI-2K).29 We report the original BILAG-2004 and the newer global BILAG-2004 score.30 Cumulative damage was recorded using the Systemic Lupus International Collaborating Clinics/ACR-Damage Index.31 A fasting blood sample was drawn for assessment of blood glucose, lipid profile, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, complement levels and autoantibody titres by CMFT laboratories. Adiponectin, vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 (VCAM-1) and vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) were measured using DuoSet ELISA development kits (R&D Systems, Abingdon, UK). Plasma soluble endothelial protein C receptor (sEPCR) was measured by ELISA (Adipobiotech, Beijing, China). Fasting serum insulin was measured by ELISA (ultrasensitive solid phase ELISA; DRG, Marburg, Germany), and the homoeostatic model assessment of insulin resistance (HOMA-IR) was calculated using the HOMA2 model.32

Assessment of endothelial damage and dysfunction

The methodologies used to assess endothelial damage and dysfunction are described in full in online supplementary file 1. In brief, EMPs were quantified in platelet-poor plasma, generated using a two-step centrifugation regimen. These platelet-poor plasma samples were stored at −80°C and analysed in batches. EMPs were enumerated (n/ml) by flow cytometry, after the addition of counting beads, and defined as CD31-postive, annexin V-positive and CD42b-negative events. FMD of the brachial artery was performed using B-mode ultrasound and automated edge-tracking software as per guidelines.33 The brachial artery was imaged longitudinally proximal to the antecubital fossa, and the probe fixed in place. A blood pressure (BP) cuff was placed around the mid-forearm. After the baseline diameter had been recorded, the BP cuff was inflated to 50 mm Hg above systolic BP, to at least 200 mm Hg, for 5 min and then deflated. Reactive hyperaemia was confirmed using Doppler ultrasound. The brachial artery diameter was recorded continuously, and endothelial-dependent brachial artery dilatation (EDD) was recorded 60 s after cuff deflation. Peak diameter was also recorded if this did not occur at 60 s. Sublingual glyceryl trinitrate was then used to assess endothelial-independent brachial artery dilatation.

Statistical analysis

A sample size calculation was performed for a co-primary outcome (change in FMD (%) over time) using data from preliminary validation studies.33 On the basis of a mean (SD) FMD (%) of 7.01% (1.77) on serial FMD measurements within one individual, a sample size of 13 patients would give 80% power at 5% significance to detect a 2% change in FMD over time. A recruitment target of 30 cases was set to allow for a 20% dropout rate. Fifteen healthy controls would provide 80% power to detect a 2% difference in FMD (%) between cases and controls. Significance of between-group differences was assessed using a two-sided t test or Mann–Whitney U test for continuous variables and χ2 test for categorical variables. Correlation between measures was assessed using Spearman's correlation coefficient. Linear regression was used to assess the association between SLE and endothelial damage/dysfunction. Data analysis was performed using the Stata V.10 software package.

Results

Twenty-seven patients with active SLE and 22 healthy controls were assessed. Baseline characteristics of cases and controls are described in tables 1 and 2. Fourteen (51.9%) patients were starting standard immunosuppression, six of whom were naïve to immunosuppressant therapy. Thirteen (48.1%) patients were starting rituximab, all of whom had either received (and had failed to respond to) standard immunosuppressant therapy (n=10) or were receiving a further cycle of therapy with biological agent (n=3). The most common indications for changing therapy were active lupus arthritis (n=8) and active lupus nephritis (n=9).

Table 1.

Demographic, clinical and laboratory variables of SLE cases and age- and gender-matched healthy controls

| Variable | SLE patients (n=27) | Controls (n=22) | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years), mean (SD) | 41.5 (14.1) | 38.5 (9.3) | 0.56 |

| Female | 26 (96.3) | 19 (86.3) | 0.96 |

| Caucasian | 17(63.0) | 20 (91.0) | 0.20 |

| BP systolic (mm Hg) | 131 (103, 144) | 119 (114, 127) | 0.78 |

| BP diastolic (mm Hg) | 76 (66, 86) | 77 (69, 80) | 0.84 |

| AHT therapy | 12 (44.0) | 0 (0) | 0.002 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 25.7 (21.5, 28.5) | 25.1 (23.1, 30.8) | 0.42 |

| WC (cm) | 80 (74, 91.6) | 80 (72, 93.5) | 0.86 |

| Total cholesterol (mmol/l) | 5.2 (4.6, 6.7) | 5.54 (4.83, 6.87) | 0.54 |

| HDL-cholesterol (mmol/l) | 1.33 (1.15, 1.61) | 1.66 (1.46, 1.78) | 0.06 |

| LDL-cholesterol (mmol/l) | 2.71 (1.92, 3.6) | 3.01 (2.70, 3.58) | 0.35 |

| Triglycerides (mmol/l) | 1.36 (0.90, 1.87) | 0.88 (0.64, 1.00) | 0.01 |

| Lipid-lowering therapy | 3 (11) | 0 (0) | 0.18 |

| Glucose (mmol/l) | 4.40 (4.1, 5.0) | 4.9 (4.8, 5.1) | 0.05 |

| Diabetes | 2 (7.4) | 0 (0) | 0.28 |

| Family history of CVD | 10 (43.5) | 4 (18.2) | 0.09 |

| MetS | 11 (40.7) | 1/15 (6.7) | 0.03 |

| Fasting insulin (mU/l) | 16.3 (12.4, 22.9) | 14.0 (12.2, 20.6) | 0.55 |

| HOMA2-IR | 2.3 (1.9, 3.0) | 2.0 (1.8, 2.9) | 0.50 |

| Adiponectin (mg/l) | 3.57 (2.46, 5.90) | 2.93 (2.42, 3.60) | 0.12 |

| hsCRP (mg/l) | 2.4 (0.5, 5.1) | 0.51 (0.26, 2.83) | 0.09 |

Unless otherwise stated, values are n (%) or median (IQR).

AHT, anti-hypertensive; BMI, body mass index; BP, blood pressure; CVD, cardiovascular disease; HDL, high-density lipoprotein; HOMA2-IR, homoeostatic model assessment of insulin resistance; hsCRP, high-sensitivity C-reactive protein; LDL, low-density lipoprotein; MetS, metabolic syndrome; SLE, systemic lupus erythematosus; WC, waist circumference.

Table 2.

Clinical and immunological features of SLE patients at entry into study (n=27)

| Feature (n=27) | n (%) or median (IQR)* |

|---|---|

| Disease duration (years) | 7.0 (3.5, 12)* |

| ANA-positive ever | 27 (100) |

| ANA-positive at baseline visit | 23 (85.2) |

| Elevated anti-dsDNA antibody† | 7 (25.9) |

| Low C3† | 3 (11.1) |

| Low C4† | 10 (37.0) |

| Anti-cardiolipin antibody-positive† | 8 (29.6) |

| Lupus anticoagulant present | 1 (3.7) |

| Total BILAG-2004 ‘A’ scores (n) | 27 |

| Total BILAG-2004 ‘B’ scores (n) | 16 |

| Global BILAG-2004 score | 14 (12, 22)* |

| SLEDAI-2K | 6 (5,13)* |

| SLICC/ACR-DI | 1 (1,2)* |

| Oral corticosteroids | 24 (88.9) |

| Average daily corticosteroid dose (mg) | 12.5 (10, 17.5)* |

| Current immunosuppressant use | 12 (44.4) |

| Current antimalarial use | 20 (74.1) |

*Defined as positive/present at study entry unless stated.

†As per laboratory reference range.

ACR, American College of Rheumatology; ANA, antinuclear antibodies; BILAG, British Isles Lupus Assessment Group Disease Activity Index; DI, Damage Index; dsDNA, double-stranded DNA; SLE, systemic lupus erythematosus; SLEDAI-2K, SLE Disease Activity Index 2000; SLICC, Systemic Lupus International Collaborating Clinics.

Endothelial damage and dysfunction in SLE

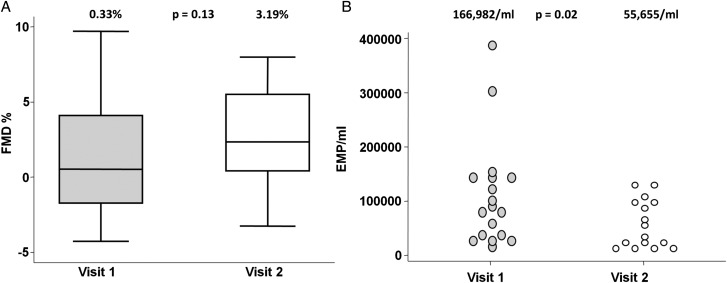

Patients with active SLE had significantly elevated CD31+/annexin V+/CD42b− EMPs (157 548/ml (59 906, 278 775) vs 41 025/ml (30 179, 98 082); p=0.001) and impaired FMD (1.63% (−1.22, 5.32) vs 5.49% (3.02, 8.57); p=0.04) compared with controls (figure 1). Total annexin V+ MPs were higher in SLE patients than controls (958 494/ml (593 399, 1 342 930) vs 450 000(315 549, 549 059) p=0.02). VCAM-1, VEGF and sEPCR were also higher in SLE patients, but both brachial artery diameter and endothelial-independent dilatation were similar (table 3). There was a moderate correlation between CD31+/annexin V+/CD42b− EMP count and FMD (%) (r2=−0.40; p=0.006) in all subjects, which was similar in SLE patients only (r2=−0.42; p=0.008). There was also a significant correlation between VCAM-1 and CD31+/annexin V+/CD42b− EMP count (r2=0.28; p=0.03). EMP count did not correlate with global BILAG-2004 score (r2=0.19, p=0.20) or SLEDAI-2K (r2=0.16, p=0.27). In a multiple regression model including SLE, age, BP, total cholesterol, glucose and estimated glomerular filtration rate, SLE was independently associated with CD31+/annexin V+/CD42b− EMP levels (B coefficient 145 (29, 260); p=0.02).

Figure 1.

(A) Reduced flow-mediated dilatation (FMD) and (B) elevated CD31+/annexin V+/CD42b− endothelial microparticles (EMPs) in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) versus controls.

Table 3.

Endothelial function and damage in SLE cases compared with controls

| SLE (n=27) | Control (n=22) | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline BA diameter (mm) | 3.34 (3.10, 3.84) | 3.34 (3.12, 4.07) | 0.89 |

| % FMD (at 60 s) | 1.63 (−1.22, 5.32) | 5.49 (3.02, 8.57) | 0.04 |

| % FMD (maximum) | 2.86 (0.60, 5.32) | 6.81 (3.46, 8.57) | 0.03 |

| % GTN dilatation | 15.3 (11.9, 19.1) | 12.0 (10.3, 17.3) | 0.43 |

| FMD <5% (at 60 s) | 75% | 43% | 0.04 |

| EMP (n/ml) | 157548 (59906, 278775) | 41,025 (30179, 98082) | 0.001 |

| VCAM-1 (ng/ml) | 488 (348, 555) | 289 (272, 317) | <0.001 |

| VEGF (pg/ml) | 108 (57, 156) | 55 (42, 153) | 0.23 |

| sEPCR (ng/ml) | 49.3 (38.0, 67.3) | 43.2 (38.4, 63.3) | 0.06 |

Unless otherwise indicated, values are median (IQR).

BA, brachial artery; EMP, endothelial microparticle; FMD, flow-mediated dilatation; GTN, glyceryl trinitrate; sEPCR, soluble endothelial protein c receptor; VCAM-1, vascular cell adhesion molecule-1; VEGF, vascular endothelial growth factor.

Effect of improved disease control on endothelial damage and dysfunction in active SLE

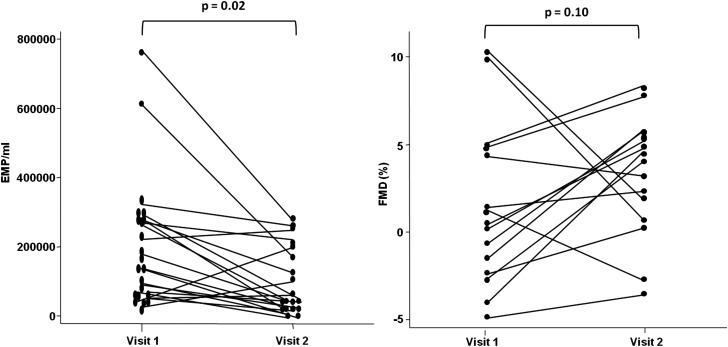

Twenty-two (81.5%) patients returned for follow-up after a median (IQR) interval of 20 (16, 22) weeks; their characteristics are described in table 4. Twelve patients received standard immunosuppressive therapies and 10 received rituximab. The characteristics of patients who failed to return did not differ from those followed-up (data not shown). Disease activity improved significantly over time. Median (IQR) change in global BILAG-2004 score was −11 (−18, −3), and change in SLEDAI-2K was −5 (−9, −2). No significant changes in traditional CHD risk factors, obesity indices, insulin metabolism or brachial artery diameter were observed over the study period. Although the median (IQR) daily prednisolone dose at follow-up remained stable at follow-up (12.5 (10, 17.5) mg; median change 0 (0–2.5) mg), dose changes were observed within individuals. The dose remained identical in nine patients, changed by ±2.5 mg in eight patients, and changed by ±5 mg in four patients. Oral prednisolone was stopped in just one individual. Total annexin V+ MPs declined over time (991 513(492 455, 1 227 363) vs 660 852 (333 964, 1 119 514); p=0.08). Median (IQR) CD31+/annexin V+/CD42b− EMP count (n/ml) improved significantly and was comparable at follow-up to controls (162 265/ml (59 906, 278 775) vs 55 655/ml(29 475, 188 659); p=0.02) (figure 2). When the two individuals with the highest EMP count were excluded, EMP counts still improved significantly (157 548/ml (59 906, 272 643) vs 55 655/ml (29 475, 188 659); p=0.03). One of these patients had lupus-associated cryoglobulinaemic vasculitis and the other had lupus nephritis, and both received rituximab. Median (IQR) change in absolute CD31+/annexin V+/CD42b− EMP count was −87 998/ml (−184 433, +4949), and percentage change was −63.8% (−79.6, 1.6). Median (IQR) FMD (%) at 60 s also improved over time (0.64% (−2.31, 4.47) vs 4.56% (1.71, 5.87); p=0.10), and the median (IQR) change in EDD was +3.54% (−1.61, 6.2). Although not our primary outcome, we also noted that patients treated with rituximab had a non-significant greater improvement in global BILAG-2004 score (median (IQR) change −13 (−25, −10) vs −5 (−16, 0); p=0.18), EMP count (median (IQR) change −107 549 (−184 433, 50 000) vs −81 886 (−189 393, −14 654); p=0.18), and FMD (+4.76% (+3.54, +6.3) vs +1.76% (−1.61, +3.89 p=0.28), compared with standard therapy. Overall, there was a moderate correlation between change in EMP count (%) and change in global BILAG-2004 score (r2=0.40 p=0.08), but change in EMP (%) did not correlate with change in FMD (%) (r2=0.11 p=071).

Table 4.

Clinical, laboratory and vascular features in SLE patients (n=22) over time

| Feature | Baseline | Follow-up | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| BP systolic (mm Hg) | 131 (104, 144) | 134 (118, 154) | 0.24 |

| BP diastolic (mm Hg) | 77 (66, 85) | 75 (67, 85) | 0.88 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 26.6 (22.5, 28.5) | 26.7 (24.2, 32.7) | 0.34 |

| WC (cm) | 84.9 (76, 94) | 86 (78.5, 94.7) | 0.55 |

| Total cholesterol (mmol/l) | 5.22 (4.71, 6.32) | 5.19 (4.60, 6.37) | 0.81 |

| HDL-cholesterol (mmol/l) | 1.33 (1.24, 1.59) | 1.45 (1.33, 1.63) | 0.32 |

| LDL-cholesterol (mmol/l) | 2.86 (1.90, 3.60) | 2.66 (2.33, 3.47) | 0.88 |

| Triglycerides (mmol/l) | 1.45 (0.9, 1.9) | 1.1 (0.9, 1.62) | 0.34 |

| Glucose (mmol/l) | 4.4 (4.1, 5.1) | 4.7 (4.1, 4.9) | 0.81 |

| MetS | 10 (45.5) | 9 (40.9) | 0.86 |

| hsCRP (mg/l) | 2.47 (0.96, 5.11) | 4.57 (1.36, 7.37) | 0.15 |

| Adiponectin (mg/l) | 3.60 (2.76, 5.90) | 3.80 (2.96, 4.84) | 0.58 |

| Fasting insulin (mU/l) | 16.1(12.4, 22.9) | 17.2 (11.8, 26.4) | 0.77 |

| HOMA2-IR | 2.4 (1.8, 4.0) | 2.6 (1.8, 3.7) | 0.80 |

| SLEDAI-2K | 6 (4, 14) | 4 (2, 6) | <0.001 |

| Global BILAG-2004 score | 17 (12, 22) | 3 (2, 9) | <0.001 |

| Elevated anti-dsDNA | 9 (40.9) | 5 (22.7) | 0.23 |

| Low complement | 7 (31.8) | 4 (18.2) | 0.44 |

| Baseline BA diameter (mm) | 3.53 (3.12, 3.85) | 3.38 (3.21, 3.85) | 0.81 |

| % FMD (at 60 s) | 0.64 (−2.31, 4.47) | 3.52 (0.98, 5.50) | 0.10 |

| % FMD (maximum) | 1.40 (0.54, 4.47) | 4.56 (1.71, 5.87) | 0.19 |

| FMD <5% (at 60 s) | 86.7% | 66.7% | 0.20 |

| EMPs (n/ml) | 162265 (59906, 278775) | 55655 (29475, 188659) | 0.02 |

| VEGF (pg/ml) | 99 (53, 155) | 71 (27, 141) | 0.14 |

| VCAM-1 (ng/ml) | 488 (375, 587) | 458 (297, 488) | 0.17 |

| sEPCR (ng/ml) | 49.3 (43.6, 67.3) | 47.0 (36.7, 72.8) | 0.79 |

Unless otherwise indicated, values are median (IQR) or n (%).

BA, brachial artery; BILAG, British Isles Lupus Assessment Group Disease Activity Index; BMI, body mass index; BP, blood pressure; CVD, cardiovascular disease; EMP, endothelial microparticle; FMD, flow-mediated dilatation; HDL, high-density lipoprotein; HOMA2-IR, homoeostatic model assessment of insulin resistance; hsCRP, high-sensitivity C-reactive protein; LDL, low-density lipoprotein; MetS, metabolic syndrome; sEPCR, soluble endothelial protein c receptor; SLE, systemic lupus erythematosus; SLEDAI-2K, SLE Disease Activity Index 2000; VCAM-1, vascular cell adhesion molecule-1; VEGF, vascular endothelial growth factor; WC, waist circumference.

Figure 2.

Improved CD31+/annexin V+/CD42b− endothelial microparticles (EMPs) and flow-mediated dilatation (FMD) in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus (n=22) over time.

Discussion

As far as we are aware, this is the first study to describe CD31+/annexin V+/CD42b− EMPs over time in an SLE cohort with active disease, and to examine their relationship with other markers of endothelial function. Patients with active SLE had significantly higher levels of circulating CD31+/annexin V+/CD42b− EMPs, independent of age and traditional CHD risk factors. Patients with active SLE also had significantly impaired FMD (%), as has been previously reported.5 34 35 We also noted a modest inverse correlation between these two measures, both in the whole cohort and in SLE patients alone. Although controls were well matched for age/gender, differences were noted at baseline between the two groups, which may have had an impact on baseline endothelial function/damage, such as an excess of CHD risk factors, a phenomenon well described in SLE.6 However, these risk factors remained stable between visits. Several studies have found a similar correlation between EMP levels and endothelial function in other disease states, such as obesity,23 renal failure22 and heart failure.36 However, SLE is an ideal model in which to examine the interaction between inflammation, endothelial dysfunction and accelerated atherosclerosis, as the cohorts are characterised by younger female patients with a chronic inflammatory disease and an excess risk of premature cardiovascular events. While FMD remains the gold standard measure of endothelial function, it is observer-dependent and difficult to standardise in multicentre studies. CD31+/annexin V+/CD42b− EMPs have many potential advantages over FMD in this regard and may be a useful adjunctive measure of cardiovascular risk in larger-scale studies.

A greater proportion of patients in this study had low FMD (defined as <5%) than has been observed previously. For example, in our previous study, 54.8% had low FMD, compared with 75% in this study, despite the earlier study examining older patients (48 years vs 41.5 years). This may in part relate to the much lower disease activity and damage scores observed in our previous cohort. We also noted that the proportion of controls with low FMD at 60 s was also higher than expected (43%). Previous studies have noted that many (42%) healthy subjects have a peak arterial diameter outside the traditional 60 s time point, occurring earlier in younger subjects and later in older subjects.37 When we used the peak FMD response, the proportion of controls with low FMD was 33% and remained lower in patients with SLE. This would suggest that the 60 s time point might not accurately capture true FMD response in all subjects, and recording both peak and 60 s brachial artery diameters as we have done is now recommended by methodological guidelines.38

We observed a significant reduction in disease activity in SLE patients who completed the study. This was associated with a significant reduction in CD31+/annexin V+/CD42b− EMPs, with post-treatment levels comparable to those seen in healthy controls. The overall change in these indices did not correlate well with each other, in part related to the variability of the two measures in a small cohort, although the study was not powered to specifically address this issue. In our cohort, factors known to affect EMPs, such as dyslipidaemia, MetS, statins and prednisolone dose, did not change significantly over the study period. We therefore hypothesise that suppression of inflammation was the key factor mediating this change in EMPs. The overall change in disease activity (change in global BILAG-2004 score) correlated modestly with change in CD31+/annexin V+/CD42b− EMP levels (r2=−0.40, p=0.08), although it should be noted that non-linear clinical disease activity indices are limited in their ability to be used in this way. Nevertheless, the trend to correlation and the stability of other key factors likely to affect EMPs supports this conclusion, as does the significant independent effect of active SLE on EMP levels at baseline. Active inflammatory disease is therefore likely to have a deleterious effect on the cardiovascular system, which appears to be modifiable over time. Our observation of a non-significant improvement in disease activity and endothelial function markers with rituximab therapy also suggests that better disease control may mitigate vascular risk in patients with SLE. However, controlled clinical trials are required to confirm this observation.

EMPs display paracrine and autocrine actions on vascular cells, and growing evidence suggests EMPs act as mediators in intracellular signalling because of their capacity to transfer a number of bioactive molecules to recipient cells.39 These bioactive molecules include growth factors, proteases, adhesion molecules, DNA and microRNAs. Functional proteins such as VEGF and endothelial nitric oxide synthase have also been identified in EMPs,40 41 and EMPs from patients with CVD have been shown to impair nitric oxide release from vascular cells.22 42 Cell culture-derived EMPs have also been shown to inhibit angiogenesis in mouse models of atherosclerosis,43 and EMPs may have vasculoprotective effects on the endothelium in acute vascular stress, such as septic shock.44 45 Therefore, rather than being inert markers of injury, EMPs may act as downstream delivery systems for proinflammatory products that are vasculoprotective in acute inflammatory conditions but which may perpetuate vascular dysfunction in chronic disease.46 Experiments are on-going in our laboratory to further examine their role in the vascular dysfunction observed in patients with SLE. There remains a lack of consensus on how best to identify and define MPs, with variation noted in the choice of cell-surface markers.47 In this study, we used a standard combination of markers to identify EMPs (annexin V+/CD31+/CD42b−),19 21 although we do acknowledge that other groups have used alternatives.24 22 CD31 is not specific to endothelial cells, and low-level expression is seen in platelets and monocytes. We did not include a B-cell marker in our flow-cytometry protocol and therefore cannot comment specifically on whether the marked fall in EMPs in patients receiving rituximab (an anti-CD20 therapy) was due to a fall in CD20+CD31+ B cells. However, monocytes do not typically express CD20, and this scenario seems unlikely.

A key strength of this study is the prospective study design and recruitment of patients with active disease that permits exploration of change in disease activity over time and its influence on endothelial dysfunction. Cross-sectional studies of stable, older cohorts of SLE patients have limited ability to explore the interplay between inflammation and cardiovascular risk. Secondly, EMPs and FMD were measured in patients and controls simultaneously, permitting the validation of EMP levels as a biomarker of endothelial dysfunction in SLE. Finally, our cohort was younger than in comparable studies, minimising the influence of age on the outcomes. We also acknowledge several limitations. First, while the sample size was sufficient to examine the primary outcome, it did not allow full and detailed exploration of secondary outcomes, such as the effect of approach to treatment. Such a question will require adequately powered clinical trials. We did not assess an inactive SLE control group and therefore cannot comment on whether SLE itself is inherently associated with elevated EMPs, although we have previously shown that stable, inactive SLE is associated with impaired FMD.5 However, we have shown that EMP levels are similar to those observed in healthy controls when disease is controlled. The inherent variability in the methods used to assess endothelial function and damage, despite optimal test conditions and techniques, also limits the exploration of secondary end points such as assessing correlation and agreement. Finally, not all patients returned for follow-up and we cannot exclude the possibility that this may have introduced some bias into our results.

We have therefore shown that CD31+/annexin V+/CD42b− EMPs are significantly elevated and FMD is significantly impaired in patients with active SLE. Improved control of inflammatory disease activity is associated with an improvement in these indices, especially EMP levels. Endothelial damage and dysfunction is therefore modifiable in patients with active SLE and raises the hypothesis that improved SLE disease control will contribute to reduced cardiovascular risk in this high-risk population.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The contribution of Mike Jackson in the flow cytometry core facility, Faculty of Life Sciences, University of Manchester, is gratefully acknowledged. INB is supported by Arthritis Research UK, The Manchester Academic Health Science Centre, the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Biomedical Research Unit Funding Scheme and the NIHR Manchester Biomedical Research Centre. The views expressed in this publication are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the NHS, the National Institute for Health Research or the Department of Health. The NIHR Manchester Wellcome Trust Clinical Research Facility hosted this study.

Footnotes

Contributors: BP was involved in study conception and design, data acquisition, data analysis and interpretation, manuscript preparation and critical revision, and final approval of the published version. AA-H, PP and APY were involved in data acquisition and interpretation, drafting of the manuscript, and final review of the published version. PH, RG and LST were involved in data acquisition, drafting of the manuscript, and final review of the published version. MYA and INB were involved in study conception and design, data acquisition, data analysis and interpretation, manuscript preparation and critical revision, and final approval of the published version

Funding: The study was funded by an Arthritis Research UK Clinical Research Fellow award (grant number 18845) and NIHR Manchester Biomedical Research Centre Fellowship.

Competing interests: None.

Ethics approval: Oldham Research Ethics Committee.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Manzi S, Meilahn EN, Rairie JE, et al. Age-specific incidence rates of myocardial infarction and angina in women with systemic lupus erythematosus: comparison with the Framingham Study. Am J Epidemiol 1997;145:408–15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Petri MA, Kiani AN, Post W, et al. Lupus Atherosclerosis Prevention Study (LAPS). Ann Rheum Dis 2011;70:760–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ahmad Y, Shelmerdine J, Bodill H, et al. Subclinical atherosclerosis in systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE): the relative contribution of classic risk factors and the lupus phenotype. Rheumatology 2007;46:983–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Roman MJ, Shanker BA, Davis A, et al. Prevalence and correlates of accelerated atherosclerosis in systemic lupus erythematosus. N Engl J Med 2003;349:2399–406 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.El-Magadmi M, Bodill H, Ahmad Y, et al. Systemic lupus erythematosus: an independent risk factor for endothelial dysfunction in women. Circ 2004;110:399–404 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bruce IN, Urowitz MB, Gladman DD, et al. Risk factors for coronary heart disease in women with systemic lupus erythematosus: the Toronto Risk Factor Study. Arthritis Rheum 2003;48:3159–67 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Esdaile JM, Abrahamowicz M, Grodzicky T, et al. Traditional Framingham risk factors fail to fully account for accelerated atherosclerosis in systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum 2001;44:2331–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bruce IN. ‘Not only...but also’: factors that contribute to accelerated atherosclerosis and premature coronary heart disease in systemic lupus erythematosus. Rheumatology 2005;44:1492–502 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Narshi CB, Giles IP, Rahman A. The endothelium: an interface between autoimmunity and atherosclerosis in systemic lupus erythematosus? Lupus 2011;20:5–13 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Panza JA, Quyyumi AA, Brush JE, Jr, et al. Abnormal endothelium-dependent vascular relaxation in patients with essential hypertension. N Engl J Med 1990;323:22–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Johnstone MT, Creager SJ, Scales KM, et al. Impaired endothelium-dependent vasodilation in patients with insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. Circ 1993;88:2510–16 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Celermajer DS, Sorensen KE, Georgakopoulos D, et al. Cigarette smoking is associated with dose-related and potentially reversible impairment of endothelium-dependent dilation in healthy young adults. Circ 1993;88: 2149–55 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Charakida M, Masi S, Luscher TF, et al. Assessment of atherosclerosis: the role of flow-mediated dilatation. Eur Heart J 2010;31:2854–61 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Muiesan ML, Salvetti M, Paini A, et al. Prognostic role of flow-mediated dilatation of the brachial artery in hypertensive patients. J Hypertens 2008;26:1612–18 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ferreira GA, Navarro TP, Telles RW, et al. Atorvastatin therapy improves endothelial-dependent vasodilation in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus: an 8 weeks controlled trial. Rheumatology 2007;46:1560–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wright SA, O'Prey FM, Rea DJ, et al. Subclinical impairment of arterial mechanics in systemic lupus erythematosus identified by arterial waveform analysis. Rheumatol Int 2007;27:961–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mallat Z, Benamer H, Hugel B, et al. Elevated levels of shed membrane microparticles with procoagulant potential in the peripheral circulating blood of patients with acute coronary syndromes. Circ 2000;101:841–3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bernal-Mizrachi L, Jy W, Jimenez JJ, et al. High levels of circulating endothelial microparticles in patients with acute coronary syndromes. Am Heart J 2003;145:962–70 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Preston RA, Jy W, Jimenez JJ, et al. Effects of severe hypertension on endothelial and platelet microparticles. Hypertension 2003;41:211–17 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Arteaga RB, Chirinos JA, Soriano AO, et al. Endothelial microparticles and platelet and leukocyte activation in patients with the metabolic syndrome. Am J Cardiol 2006;98:70–4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sinning JM, Losch J, Walenta K, et al. Circulating CD31+/Annexin V+ microparticles correlate with cardiovascular outcomes. Eur Heart J 2011;32:2034–41 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Amabile N, Guerin AP, Leroyer A, et al. Circulating endothelial microparticles are associated with vascular dysfunction in patients with end-stage renal failure. J Am Soc Nephrol 2005;16:3381–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Esposito K, Ciotola M, Schisano B, et al. Endothelial microparticles correlate with endothelial dysfunction in obese women. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2006;91:3676–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Brogan PA, Shah V, Brachet C, et al. Endothelial and platelet microparticles in vasculitis of the young. Arthritis Rheum 2004;50:927–36 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dignat-George F, Camoin-Jau L, Sabatier F, et al. Endothelial microparticles: a potential contribution to the thrombotic complications of the antiphospholipid syndrome. Thromb Haemost 2004;91:667–73 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nielsen CT, Ostergaard O, Johnsen C, et al. Distinct features of circulating microparticles and their relationship to clinical manifestations in systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum 2011;63:3067–77 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hochberg MC. Updating the American College of Rheumatology revised criteria for the classification of systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum 1997;40:1725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Isenberg DA, Rahman A, Allen E, et al. BILAG 2004. Development and initial validation of an updated version of the British Isles Lupus Assessment Group's disease activity index for patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Rheumatology 2005;44:902–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gladman DD, Ibanez D, Urowitz MB. Systemic lupus erythematosus disease activity index 2000. J Rheumatol 2002;29:288–91 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yee CS, Cresswell L, Farewell V, et al. Numerical scoring for the BILAG-2004 index. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2010;49:1665–9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gladman D, Ginzler E, Goldsmith C, et al. The development and initial validation of the Systemic Lupus International Collaborating Clinics/American College of Rheumatology damage index for systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum 1996;39:363–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Levy JC, Matthews DR, Hermans MP. Correct homeostasis model assessment (HOMA) evaluation uses the computer program. Diabetes Care 1998;21:2191–2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Corretti MC, Anderson TJ, Benjamin EJ, et al. Guidelines for the ultrasound assessment of endothelial-dependent flow-mediated vasodilation of the brachial artery: a report of the International Brachial Artery Reactivity Task Force. J Am Coll Cardiol 2002;39:257–65 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mak A, Liu Y, Chun-Man HR. Endothelium-dependent but not endothelium-independent flow-mediated dilation is significantly reduced in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus without vascular events: a metaanalysis and metaregression. J Rheumatol 2011;38:1296–303 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Stalc M, Tomsic M, Jezovnik MK, et al. Endothelium-dependent and independent dilation capability of peripheral arteries in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus and antiphospholipid syndrome. Clin Exp Rheumatol 2011;29:616–23 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bulut D, Maier K, Bulut-Streich N, et al. Circulating endothelial microparticles correlate inversely with endothelial function in patients with ischemic left ventricular dysfunction. J Card Fail 2008;14:336–40 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Black MA, Cable NT, Thijssen DH, et al. Importance of measuring the time course of flow-mediated dilatation in humans. Hypertension 2008;51:203–10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Thijssen DH, Black MA, Pyke KE, et al. Assessment of flow-mediated dilation in humans: a methodological and physiological guideline. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 2011;300:H2–12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Leroyer AS, Tedgui A, Boulanger CM. Role of microparticles in atherothrombosis. J Intern Med 2008;263:528–37 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chironi GN, Boulanger CM, Simon A, et al. Endothelial microparticles in diseases. Cell Tissue Res 2009;335:143–51 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mayr M, Grainger D, Mayr U, et al. Proteomics, metabolomics, and immunomics on microparticles derived from human atherosclerotic plaques. Circ Cardiovasc Genet 2009;2:379–88 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Boulanger CM, Amabile N, Guerin AP, et al. In vivo shear stress determines circulating levels of endothelial microparticles in end-stage renal disease. Hypertension 2007;49:902–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ou ZJ, Chang FJ, Luo D, et al. Endothelium-derived microparticles inhibit angiogenesis in the heart and enhance the inhibitory effects of hypercholesterolemia on angiogenesis. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 2011;300:E661–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mostefai HA, Meziani F, Mastronardi ML, et al. Circulating microparticles from patients with septic shock exert protective role in vascular function. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2008;178:1148–55 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Soriano AO, Jy W, Chirinos JA, et al. Levels of endothelial and platelet microparticles and their interactions with leukocytes negatively correlate with organ dysfunction and predict mortality in severe sepsis. Crit Care Med 2005;33:2540–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lozito TP, Tuan RS. Endothelial cell microparticles act as centers of matrix metalloproteinsase-2 (MMP-2) activation and vascular matrix remodeling. J Cell Physiol 2012;227:534–49 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Shet AS. Characterizing blood microparticles: technical aspects and challenges. Vasc Health Risk Manag 2008;4:769–74 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.