Abstract

Background

A considerable proportion of work absence is attributed to back pain, however prospective studies in working populations with back pain are variable in setting and design, and a quantitative summary of current evidence is lacking.

Objective

To investigate the extent to which differences in setting, country, sampling procedures and methods for data collection are responsible for variation in estimates of work absence and return to work.

Methods

Systematic searches of seven bibliographic databases. Inclusion criteria were: adults in paid employment, with back pain, work absence or return to work during follow-up had been reported. Random effects meta-analysis and meta-regression analysis was carried out to provide summary estimates of work absence and return to work rates.

Results

45 studies were identified for inclusion in the review; 34 were included in the meta-analysis. The pooled estimate for the occurrence of work absence in workers with back pain was 15.5% (95% CI 9.8% to 23.6%, n=17 studies, I2 98.1%) in studies with follow-up periods of ≤6 months. The pooled estimate for the proportion of people with back pain returning to work was 68.2% (95% CI 54.8% to 79.1%, n=13, I2 99.2%), 85.6% (95% CI 78.2% to 90.7%, n=13, I2 98.7%) and 93.3% (95% CI 84.0% to 94.7%, n=10, I2 99%), at 1 month, 1–6 months and ≥6 months, respectively. Differences in setting, risk of participation bias and method of assessing work absence explained some of the heterogeneity.

Conclusions

Pooled estimates suggest high return to work rates, with wide variation in estimates of return to work only partly explained by a priori defined study-level variables. The estimated 32% not back at work at 1 month are at a crucial point for intervention to prevent long term work absence.

What this paper adds.

Back pain leads to a considerable proportion of work absence, however prospective studies in working populations with back pain are variable in setting and design and summary of current evidence is lacking.

The pooled estimate for the occurrence of work absence in workers with back pain was 15.5% in studies with follow-up period of up to 6 months.

The pooled estimate for the proportion of people with back pain returning to work was 68.2% at 1 month, 85.6% at 1–6 months and 93.3% at ≥6 months.

Differences in setting, risk of participation bias and method of assessing work absence explained some of the heterogeneity.

Pooled estimates suggest a high return to work, however the estimated 32% not back at work at 1 month are at a crucial point for intervention to prevent long term work absence.

Introduction

Low back pain is a major problem throughout the world; it is common, and often recurrent. A recent systematic review of 165 studies on the epidemiology of back pain estimated the global 1-month period prevalence to be 23.2% (±2.9%).1 The 1-year incidence of a first ever episode of back pain has been reported to range from 6.3% to 15.4%.2 The incidence of back pain is highest in people in their 40s, while the prevalence of back pain increases with age before declining in older age groups.3 Of those people who experience activity limiting back pain, most will go on to have recurrent episodes.2

The burden of back pain, in terms of the prevalence and incidence of the condition, has been well described, but the burden of back pain from an occupational perspective is less clear. It has been estimated that 12.5% of all work absence in the UK is attributable to back pain.4 Estimates of the 1-year prevalence of sickness absence due to back pain range from 9% of the working population of New Zealand (randomly selected from the electoral roll)5 to 32% of hospital employees in Ireland.6 If people are absent from work due to back pain, early return to work is important for economic, social and health reasons. With the increase of length of work absence and disability, comes a lower probability of returning to work.7 Return to work rates in those who have short term absence due to an episode of back pain have been reported to be between 80% and 90%.4 8 9 In those with chronic occupational back pain, sustainable return to work rates range between 22% and 62% after 2 years.10

Although many studies in people with back pain report measures of work absence and return to work, the figures above demonstrate wide variation in these estimates depending on country, setting, characteristics of the study population (eg, duration of back pain), definition of work absence and return to work. Hestbaek et al11 concluded that the literature on return to work, in particular, was confusing and estimates of return to work inconclusive due to the lack of consistency in the definitions used.

The aim of this systematic review and meta-analysis was to investigate the extent to which differences in setting, country, sampling procedures and methods for data collection may be responsible for variation in estimates of work absence and return to work, in people with back pain, and provide more accurate estimates for specific settings and populations.

Methods

Selection of studies for review

Inclusion criteria

Cohort studies were included in the review if participants, at baseline, were in paid employment and had non-specific or mechanical back pain; the back pain did not have to be work related. Studies also had to report: (1) a subjective or objective outcome measure of work absence or sick leave over the follow-up period, and/or (2) data on return to work rates in workers with back pain absent from work at baseline. Cohort studies using prospectively collected data as well as studies based on retrospective analysis of existing data from insurance or employment databases were included.

Exclusion criteria

Studies that reported on patients with more generalised painful conditions (such as rheumatoid arthritis and fibromyalgia), but did not report separate results for people with back pain were excluded from this review. Studies on the prevalence of back pain related absence in a population of workers (where the absence was not necessarily due to back pain) and studies including patients on long term sick leave (more than 2 weeks’ duration) at the start of the study were excluded. Studies published in languages other than English were also excluded.

Search strategy

A systematic, comprehensive search of published and unpublished healthcare and occupational health literature was carried out. The following electronic databases were searched in May and June 2011: Medline, EMBASE, CINAHL, AMED, PsycInfo, Health Management Information Consortium Database (including King's Fund and Department of Health databases) and Web of Science. A full search strategy is available on request.

Two of three reviewers (JC, JJ, DvdW) independently assessed the titles and abstracts of potentially relevant papers identified from the search strategy against the inclusion criteria. All remaining papers were obtained and reviewed in full (by two of the three reviewers) before a final decision was made on inclusion or exclusion from the review. If consensus between the two reviewers could not be reached for a particular study, the third reviewer was consulted.

Data extraction

Data were extracted by two reviewers independently using a standardised data extraction sheet. The following data were extracted from each of the studies:

Design: analysis of prospectively collected data, or retrospective analysis of existing data on work absence (usually insurance databases).

Characteristics of the study setting and population: year data collection started, country, setting (database, primary care, secondary care, workplace, general population), sampling/recruitment process, number of participants or claims sampled, baseline characteristics of participants, the types of workplace, and the duration of back pain.

Outcome measurement: method of data collection on work absence using self-report or based on available health insurance or employer records.

Results: proportion of workers absent from work due to low back pain over the period of follow-up, duration of work absence, or proportion returning to work within a specific time period.

Outcome measures

The main outcome measures of interest were occurrence of work absence, measured by the proportion of workers with back pain absent from work over a follow-up period of at least 6 months, and return to work, measured as the proportion of workers on sick leave at baseline who return to work within 1 month (short term), 1–6 months (medium term) or more than 6 months (long term). The mean or median duration of work absence was also recorded if this was reported by study authors.

Potential sources of variation

We assessed the following study-level variables as potential sources of variation in estimates of work absence or return to work across studies:

Setting/study population: samples identified from insurance databases, general populations, healthcare settings or workplaces.

Geographical region: Europe, North America, other.

Study period during which data were collected: 1977–1990, 1991–2000, 2001–most recent (2007).

Method used to collect information on the outcome measure (work absence or return to work): using either data from self-report questionnaires or data retrieved from insurance or employer databases.

Potential bias related to study participation, assessed using the study participation domain of the quality assessment framework suggested by Hayden et al.12 The items in this domain related to clear description of the source population, sampling and recruitment methods, inclusion criteria, baseline characteristics of the study population and an adequate (≥70%) participation rate of eligible subjects. The information generated by these signalling items was used to assess the risk of participation bias, which for each study was assessed as low, moderate or high by two independent reviewers, with a third reviewer being consulted to resolve any disagreements. Studies were assessed as low risk of bias if sampling procedures were clearly described and were unlikely to introduce bias (eg, random sampling or consecutive patients); high participation rates were achieved (we used ≥70%); there was no evidence of selective non-response; and the baseline characteristics of the sample were clearly described, indicating the sample reflected the intended target population. Studies were considered to be at moderate risk of bias if they met some but not all criteria of if insufficient information made it difficult to judge the risk of bias. Studies were assessed at high risk of bias if sampling methods were likely to introduce bias (eg, inappropriate exclusions); participation rates were low (<70%), and/or there was selective non-response; and the sample was poorly described.

Data synthesis

Details are provided on setting, study population, definitions used, and estimates of the occurrence of work absence and return to work rate for the studies included in the review. Pooled estimates for return to work were calculated for return to work within 1 month, 1–6 months and longer than 6 months using a random effects model.13 As meta-analysis requires a normal distribution of data, logit transformations were applied to proportions presented for return to work, and the analysis was weighted by inverse variance of the logit transformed proportions.14 The final pooled logit results and 95% CIs were back-transformed to proportions for ease of interpretation. We used Cochran's Q test for heterogeneity with a 10% level of significance to detect inconsistency in study results, and the Higgins I2 statistic to denote the percentage of variation in study results that exceeded random error.15 16 The Higgins I2 was calculated using basic results from the meta-analysis as I2=100% × (Q−df)/Q, where Q is the Cochran heterogeneity statistic and df is the degrees of freedom.15 16 Negative values of I2 were adjusted to zero (no heterogeneity), to give an I2 between 0 and 100%, where larger values show increasing heterogeneity.15 16 We used the following simplified categorisation to classify the level of heterogeneity based on I2: low (I2 value of 25% and above), moderate (I2 value of 50% and above) and high (I2 value of 75% and above).

Meta-regression analysis was used to study the influence of a priori defined potential sources of variation, investigating one co-variable at a time: study setting, country, study period, method used to collect data on work absence, and risk of study participation bias. Pooled estimates (with 95% CI) were presented for subgroups based on these study-level variables, along with the proportion of variance explained by each study-level variable. The R-statistical package (‘meta’) was used to carry out the meta-analyses and meta-regression analyses.17

Data regarding the duration of work absence were not suitable for meta-analysis, and so the results were described in terms of the median or mean number of days off work over a specific time period, or as the mean or median duration of an episode of work absence.

Results

Study characteristics

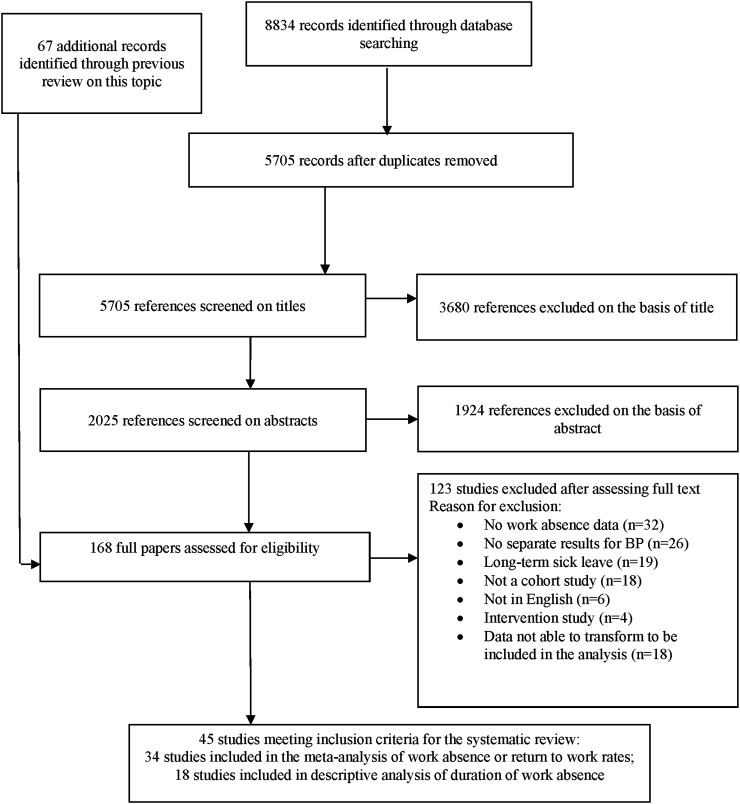

The search identified 8834 records, which resulted in 45 studies included in the review. Figure 1 shows the results of the search process and the selection of papers. Of these 45 studies, 55.5% (n=25) were assessed as low risk of participation bias, 37.7% (n=17) as moderate risk of bias and 6.8% (n=3) as high risk of bias. The data were such that a descriptive summary is given of results from 18 studies reporting on the duration of work absence,18––35 while we were able to include 34 studies in the meta-analysis of the occurrence of work absence or return to work rates.18 20 21 24––26 35––62

Figure 1 .

Flow diagram showing the results of the search and selection of papers.

A summary of the general characteristics of the included studies is presented in online supplementary table S1, and a more detailed description of design and results of each study is provided in online supplementary table S2. There were a total of 188 281 participants in the 45 included studies, ranging from 50 to 148 917 individuals or episodes of work absence.

Only four studies provided information on duration of work absence at the time of the study inception. Steenstra et al:49 at first interview participants had a mean of 18.8 (SD 6.43) days missed due to injury. Hadler et al:60 in the 30 days prior to the baseline interview, insured patients had 3.2 days of absence compared to 2.6 days of absence in uninsured patients. Linton et al:55 of the sample, 62% reported no days absence over the previous 12 months, 18% reported 1–30 days absence over the past 12 months and 20% reported ≥30 days absence over the past 12 months. Note that 12 months covers the period of follow-up (6 months) plus the period before entry into the study (6 months). Nordin et al:56 duration of absence was <28 days in 60% of participants employed in a utility company and 45% in participants employed in a transportation authority.

Healthcare settings were used to identify back pain populations in 18 studies, 10 studies were carried out in the workplace, 14 identified episodes of back pain from insurance or employer databases, and three used general population samples to identify workers with back pain.

The healthcare settings varied, from primary care settings to emergency departments, outpatient clinics and hospital settings. The workplaces included a shipbuilding company, two industrial plants, retail stores and a utility company (see online supplementary table S2).

Most of the studies were carried out in European countries (46.6%, n=21). A further 42.2% (n=19) of studies were carried out in North America, and five studies were conducted in other countries: Israel, Australia, Japan and Argentina. Approximately half of the studies collected data on work absence by self-report from the patients (48.8%, n=22), with the remaining 23 studies collecting data from insurance or work absence databases (see online supplementary table S1).

Duration of work absence

The durations of work absence, presented as either median or mean number of days, are summarised in online supplementary table S3. The median duration of work absence (nine studies) ranged from 14 to 24 days in studies conducted in back pain populations identified from healthcare settings, from 7 to 61 days in database studies, and from 5 to 28 days in workplace samples with back pain. One population-based cohort study reported a median duration of work absence of 12 days for men and 7 days for women with back pain.18

The mean duration of work absence was reported in 18 studies which showed wide variation in setting, sampling frame and length of follow-up (see online supplementary table S3). Of these 18 studies, 38.9% (n=7) were assessed as low risk of participation bias, 44.4% (n=8) as moderate risk of bias and 16.7% (n=3) as high risk of bias. Mean sick leave ranged from 2.6 to 84 days in studies conducted in a healthcare setting, from 1.2 to 41.1 days in data taken from database studies, and from 5.0 to 21.2 days in studies conducted in workplace populations with back pain.

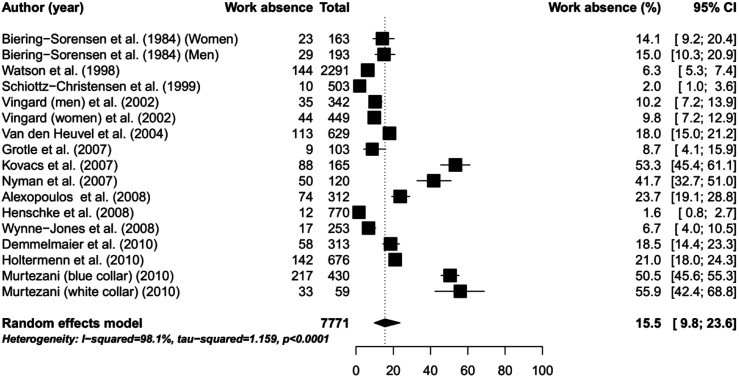

Occurrence of work absence

Figure 2 presents estimates from individual studies of the proportion of workers with back pain with an episode of work absence during follow-up. Of these 14 studies 42.9% (n=6) were judged to have low risk of bias, 57.1% (n=8) moderate risk of bias and none as high risk of bias. The pooled occurrence was 15.5% (95% CI 9.8% to 23.6%, n=14 studies contributing 17 sets of data) in studies with follow-up periods of 6 months or longer. The I2 statistic was 98.1%, indicating large heterogeneity in study findings.

Figure 2.

Summary of results regarding occurrence (%) of work absence in back pain populations based on studies with at least 6 months’ follow-up.

The results of the meta-regression analysis including pooled estimates for subgroups of studies are shown in table 1. There were no statistically significant associations between the characteristics of the studies and work absence in back pain populations. However, the meta-regression analysis demonstrated that some of the variance in estimates of work absence could be explained but study setting or use of a database. Study setting explained the most variance at 21.5%, with studies conducted in either a healthcare setting or using samples from insurance databases reporting the lowest estimate of work absence (pooled estimates 7.9% and 11.8%, respectively), compared to studies carried out in the workplace and using population-based samples (pooled estimates 35.0% and 20.8%, respectively).

Table 1.

Results of meta-regression analysis of occurrence (%) of work absence in back pain populations (follow-up 6 months or longer)

| Number of studies | Pooled estimate (95% CI) | Meta-regression | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| p Value | Explained variance (%) | |||

| All studies | 17* | 15.5 (9.8 to 23.6) | ||

| Setting | 0.109 | 21.5 | ||

| Insurance database | 2 | 11.8 (3.3 to 34.0) | ||

| Population | 4 | 20.8 (12.1 to 33.6) | ||

| Healthcare | 7 | 7.9 (2.7 to 20.7) | ||

| Workplace | 4 | 35.0 (18.4 to 56.1) | ||

| Geographical area | 0.539 | 0.0 | ||

| North America | 14 | 14.4 (9.6 to 21.1) | ||

| Europe | − | − | ||

| Other | 3 | 21.6 (2.6 to 73.9) | ||

| Study period† | 0.888 | 0.0 | ||

| 1977–1990 | 2 | 14.6 (11.3 to 18.7) | ||

| 1991–2000 | 6 | 10.7 (5.5 to 20.0) | ||

| 2001–2007 | 7 | 14.0 (7.2 to 25.4) | ||

| Assessment | 0.203 | 4.5 | ||

| Electronic record | 5 | 25.2 (11.1 to 47.7) | ||

| Self-reported | 12 | 12.4 (6.8 to 21.5) | ||

| Participation bias | 0.278 | 1.1 | ||

| Low risk of bias | 7 | 10.7 (4.1 to 25.3) | ||

| Moderate risk of bias | 10 | 19.5 (11.2 to 31.8) | ||

| High risk of bias | − | − | ||

There was a difference in the proportion of absence in back pain populations dependent on how assessment was carried out, with studies using electronic records resulting in a higher pooled rate of absence compared to studies using self-report (pooled estimate 25.2%, 95% CI 11.1% to 47.7% vs 12.4%, 95% CI 6.8% to 21.5%). This difference however was not significant, and this factor explained only 4.5% of the variance.

Lastly, study participation bias accounted for 1.1% of the variance, with a lower proportion of work absence (pooled estimate 10.7%, 95% CI 4.1% to 25.3%) being estimated in studies showing a low risk of bias compared to studies with a moderate risk of bias (pooled estimate 19.5%, 95% CI 11.2% to 31.8%). None of the studies were considered to have a high risk of participation bias.

Neither geographical area nor study period explained any variation in estimates of the occurrence of work absence.

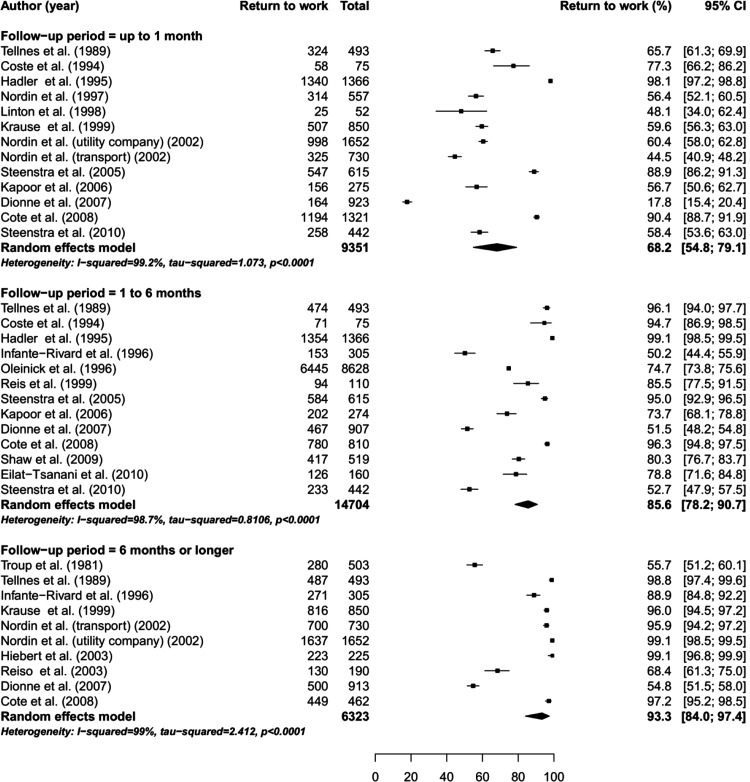

Return to work

Estimates of the proportion of people with back pain returning to work within a specific period of time from individual studies, together with their pooled estimate, are shown in figure 3. Of the 20 studies included in these analyses, 80.0% (n=16) were assessed as low risk of participation bias, 15.0% (n=3) were classed as moderate risk of bias and 5.0% (n=1) as high risk of bias. The pooled estimate of the proportion of people returning to work was 68.2% (95% CI 54.8% to 79.1%, n=12), 85.6% (95% CI 78.2% to 90.7%, n=13) and 93.3% (95% CI 84.0% to 97.4%, n=9) at 1 month, 1–6 months and 6 months or longer follow-up periods, respectively. The I2 statistic was >90%, indicating large between-study heterogeneity.

Figure 3.

Summary of results regarding return to work following back pain related work absence (%).

Table 2 presents the results of the meta-regression analysis and pooled estimates for subgroups of studies for return to work rates. Setting showed no significant association with return to work rates at up to 1 month and 1–6 months, but at 6 months or longer differences in setting were significant (p=0.003) and explained 78.8% of the variance, with the pooled estimate for return to work in studies from healthcare settings being lower (68.9%, 95% CI 54.2% to 80.6%) than those using samples from either insurance databases or workplace settings (97.7%, 95% CI 92.7% to 99.3% and 98.1%, 95% CI 95.7% to 99.2%, respectively).

Table 2.

Results of meta-regression analysis of return to work rates (%) following back pain related work absence

| Up to 1 month | 1–6 months | 6 months or longer | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | Pooled estimate (95% CI) | Meta-regression | n | Pooled estimate (95% CI) | Meta-regression | n | Pooled estimate (95% CI) | Meta-regression | ||||

| p Value | Explained variance (%) | p Value | Explained variance (%) | p Value | Explained variance (%) | |||||||

| All studies | 13 | 68.2 (54.8 to 79.1) | 13 | 85.6 (78.2 to 90.7) | 10 | 93.3 (84.0 to 97.4) | ||||||

| Setting | 0.787 | 0.0 | 0.403 | 0.4 | 0.003 | 78.8 | ||||||

| Insurance database | 4 | 60.3 (56.6 to to 63.9) | 4 | 79.0 (64.3 to 88.7) | 2 | 97.7 (92.7 to 99.3) | ||||||

| Population | – | – | – | |||||||||

| Healthcare | 5 | 68.1 (28.9 to 91.8) | 7 | 84.4 (69.2 to 92.9) | 4 | 68.9 (54.2 to 80.6) | ||||||

| Workplace | 4 | 75.6 (51.4 to 90.0) | 2 | 95.7 (94.2 to 96.8) | 4 | 98.1 (95.7 to 99.2) | ||||||

| Geographical area | 0.727 | 0.0 | 0.303 | 5.9 | 0.323 | 1.4 | ||||||

| North America | 9 | 66.1 (49.5 to 79.6) | 9 | 80.4 (69.5 to 88.1) | 7 | 95.5 (82.5 to 98.9) | ||||||

| Europe | 4 | 72.8 (51.6 to 87.0) | 3 | 95.4 (94.0 to 96.5) | 3 | 84.7 (58.3 to 95.6) | ||||||

| Other | – | 2 | 81.8 (74.2 to 87.5) | – | ||||||||

| Study period* | 0.718 | 0.0 | 0.905 | 0.0 | 0.370 | 7.1 | ||||||

| 1977–1990 | 1 | 65.7 (61.4 to 69.8) | 2 | 89.4 (51.1 to 98.6) | 1 | 98.8 (97.3 to 99.5) | ||||||

| 1991–2000 | 8 | 75.1 (51.8 to 89.4) | 9 | 87.9 (74.8 to 94.7) | 6 | 91.2 (74.7 to 97.3) | ||||||

| 2001–2007 | 2 | 52.6 (37.1 to 67.5) | – | 2 | 98.0 (91.7 to 99.6) | |||||||

| Assessment | 0.261 | 3.3 | 0.836 | 0.0 | 0.008 | 57.4 | ||||||

| Electronic record | 6 | 57.3 (51.6 to 62.9) | 4 | 83.7 (74.6 to 89.9) | 5 | 98.1 (96.1 to 99.0) | ||||||

| Self-reported | 7 | 76.4 (43.8 to 93.1) | 9 | 86.6 (72.3 to 94.1) | 5 | 79.0 (62.7 to 89.3) | ||||||

| Participation bias | 0.039 | 27.3 | 0.014 | 39.5 | 0.363 | 3.6 | ||||||

| Low risk of bias | 10 | 58.6 (45.9 to 70.3) | 11 | 79.8 (71.4 to 86.2) | 8 | 94.5 (83.1 to 98.4) | ||||||

| Moderate risk of bias | 3 | 89.5 (57.2 to 98.2) | 2 | 98.2 (92.7 to 99.6) | 1 | 97.2 (95.2 to 98.4) | ||||||

| High risk of bias | – | – | 1 | 55.7 (51.3 to 60.0) | ||||||||

*Two studies did not report study period.

n, number of studies.

The geographical region from which studies originated and period during which the study was carried out showed a weak non-significant association with estimates of return to work at the 1–6 month and 6 month or longer periods. Study period also showed a weak non-significant association with estimates of return to work at 6 months or longer.

The method of assessment of return to work accounted for 57.4% of the variance at 6 months or longer (p=0.008). Studies using self-reported data had a pooled estimate of 79.0% (95% CI 62.7% to 89.3%) of back pain absentees returning to work at 6 months or longer compared to studies using electronic records where the pooled estimate was 98.1% (95% CI 96.1% to 99.0%).

Estimates of return to work within 1 month and 1–6 months were significantly associated with the risk of study participation bias, with a higher pooled estimate of participants returning to work being reported for studies with a moderate risk of bias when compared with those with a low risk of bias (p=0.039 and 0.014, respectively). The risk of study participation bias explained 27.3% and 39.5% of the variance at up to 1 month and 1–6 months, respectively. There was no significant effect of this source of bias at the 6 months or longer follow-up period. At up to 1 month, studies with a low risk of bias had a pooled estimate of return to work of 58.6% (95% CI 45.7% to 70.3%) compared to 89.5% (95% CI% 57.2 to 98.2%) in studies with a moderate risk of bias. Analysis of the data for the 1–6 month period also demonstrated that studies with a low risk of bias had a lower estimated return to work compared to those with a moderate risk of bias: 79.8% (95% CI 71.4% to 86.2%) and 98.2% (95% CI 92.7% to 99.6%), respectively.

Discussion

Summary of main findings

The results of the systematic review and meta-analysis indicate that almost one fifth of workers with back pain take some absence over a period of 6 months or longer. Estimates showed wide variability across studies that could not be explained by geographical region, setting, study period, methods of data collection on work absence or risk of participation bias. The majority of individuals who have a period of absence as a result of back pain will return to work; pooled estimates were 68% at up to 1 month, 85% at 1–6 months and 93% at 6 months follow-up. Variability in estimates was partly explained by study participation bias, methods of data collection and study setting, with higher return to work rates reported in studies using samples from insurance databases, electronic recorded assessment of work absence and those studies judged to have a moderate risk of participation bias, compared to studies with a low risk of participation bias.

Sources of heterogeneity

There was a large amount of between-study variability in estimates of the occurrence of work absence and return to work, with I2 being >90% for all analyses. Heterogeneity was investigated using meta-regression analysis to examine whether the variability could be explained by several a priori defined study-level characteristics, but this provided only limited explanation. Some of the unexplained observed heterogeneity may be the result of differences in study-level factors that were not considered in this meta-analysis, such as the specific definitions used for absence and return to work. However, it is likely that individual-level differences explain most of the variation, such as differences in the back pain duration of study participants, the level of pain and disability reported by study participants, or work conditions. Individual level factors might have provided more insight into the reasons for the observed variability in estimates of work absence and return to work in workers with back pain, but could not be addressed in this analysis. Furthermore, this review and meta-regression was only able to examine the effect of potential sources of variance individually; ideally the analysis would also have looked at potential cumulative variance but this was not possible due to the limited number of studies eligible for inclusion in each analysis.

There were some interesting findings when investigating potential sources of variation that warrant further consideration, in particular for estimates of return to work. First, estimates of return to work rates based on studies with long-term follow-up were lower in studies conducted in the healthcare setting compared to studies conducted in other settings. This is likely to reflect differing characteristics of the study population, with participants recruited from a healthcare setting having more severe back pain and related symptoms, either making them less likely to return to work, or waiting for treatment to finish before returning to work.

Of studies included in the return to work analysis, only three had a moderate risk of participation bias and only one had a high risk of bias. Nevertheless, study participation bias showed a significant association with the estimates of return to work in the shorter term (up to 6 months), such that a low risk of participation bias was consistently associated with a lower estimate of return to work. The reasons for this are not entirely clear. However, those studies with a moderate or high risk of bias are those in which the study population is less likely to adequately reflect the source population, as a result of poor sampling and recruitment procedures, or poor participation rates. Those individuals who are less likely to return to work may also be less likely to be included in the baseline samples of studies with moderate or high risk of participation bias. It is important therefore to assess the risk of participation bias in systematic reviews of observational studies and their potential association with reported outcomes. Studies where data on work absence were extracted from electronic records were significantly more likely to report a lower proportion of participations returning to work at up to 1 month but a significantly higher proportion returning to work at 6 months or longer compared to self-report. Again the reasons for this are unclear; however it may be proposed that there is a delay in recording return to work on electronic records at 1 month, and in most insurance databases the first 2–5 days of work absence are not recorded. Simple return to work status at 6 months as recorded in electronic records may be less informative than self-report from which it may be possible also to investigate partial return to work and recurrent periods of absence. Further details of the specific definitions of return to work in each of the studies would be required to explore these propositions fully.

Definition of work absence and return to work

Heitz et al63 proposed the inclusion of standardised measures of a range of work outcomes, to permit comparisons between studies. Although the methods for assessing absence were generally quite consistent, the definitions of absence that were used varied considerably. It has been noted that although absence would appear to be straightforward to measure, there are many and varied definitions of absence that relate to the absence episode (eg, new/current/past absence), duration (eg, calendar days, working days, compensated days, hours) and person (number taking absence, percentage absence).64 65 Hensing et al66 suggest five measures that should be included when recording absence in an attempt to introduce some consistency across studies: frequency of absence, length of absence, incidence rate, cumulative incidence, and duration of absence. Of the studies that were included in the current review, the majority of these measures were missing.

Variability in definitions was also found in measures of return to work and it is important to note that return to work does not equate to ‘full recovery’ or working at full capacity. Research into the measurement of return to work suggests that there are difficulties associated with reliability (particularly of self-reported status), and that the validity of measures should be examined as common measures of return to work lack information on sensitivity and specificity.58 Additionally, Anema et al10 urge caution when comparing return to work rates across countries as a result of differing systems of disability benefits and applied work interventions, which have been demonstrated to have an impact on the rates of absence.67

In conclusion, this review has identified the important influence of research methodology when conducting studies with an occupational outcome. The observed heterogeneity demonstrates a need for more consistency in the definitions and measurement of both absence and return to work in order to accurately relate the literature to the occupational burden in people with back pain. There has been a move within the back pain literature to standardise terminology68 and this is beginning to transfer into the occupational health literature.39

Length and timing of follow-up

It has been proposed that the assessment of outcomes should take place at a common and clinically relevant time point and the findings of the current review would support this proposal.63 The studies included in this review varied considerably in terms of length of follow-up and timing of outcome measurements, which may have influenced findings regarding occurrence of work absence or return to work rates. Each study was allocated to a category relating to time-period of outcome up to 1 month, 1–6 months and 6 months or longer. These categories were selected to reflect the most common follow-up periods in the studies, and the potential for policy consequences, with no specific intervention being required for people (approximately 68% based on this review) who have returned to work within 1 month, while those who have not returned to work by 6 months (approximately 15%) may be eligible for state support in the form of benefits (eg, in the UK). While 1 month may be considered an arbitrary time point, those who have not returned to work at 1 month (estimated at 32%) are at a crucial point for intervention to prevent longer term absences and high costs associated with benefits, in addition to the adverse health, social and economic consequences for the individual.7 This group could be targeted for identification of obstacles to working with health conditions,69 with a move towards early screening for occupational factors associated with long-term back disability.70 Screening and targeting of risk factors for poor outcome has been demonstrated to be clinically and cost effective with regard to treatment for back pain, with a positive effect on work absence in addition to pain,71 but the method now needs to be more specifically applied to occupational risk factors of back pain in order to prevent long-term absence and promote return to work. At present there is insufficient evidence on prognostic factors, which means that we cannot yet accurately predict (at the start of work absence) who are likely to have a poor long-term outcome. There is currently little evidence to support a strategy in which early intervention is targeted only to those who need it. Therefore, the most effective and efficient approach may be a stepwise approach, in which more proactive intervention is offered to those still absent from work at a time after which current evidence indicates the majority have returned to work with no or minimal intervention. Intervening at an earlier stage risks being costly due to ‘treating’ people with back pain who are likely to return to work regardless. However, additional (randomised) research needs to take place to clarify if 1 month is indeed the most appropriate point at which to intervene in those who are absent from work, and which interventions are likely to be most cost effective.

Conclusions

In conclusion, this review summarises the evidence, from a wide range of settings and populations, on the proportion of workers with back pain who experience an episode of work absence, and the proportions who return to work in the short, medium and long term. Pooled estimates suggest high return to work rates in most studies, but also reveal wide variation in estimates of return to work partly explained by differences in study setting or study participation bias and in the methods used for measuring work absence and return to work. Further research should focus on addressing these methodological issues in addition to investigating the effectiveness and efficiency of screening and targeting individual-level risk factors in the estimated 32% of workers still absent from work at 1 month in order to prevent long-term work absence in an estimated 7% of workers with back pain.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This paper presents independent research commissioned by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Post-Doctoral Fellowship funding scheme (grant number PDF-2009-02-54). The views expressed in this paper are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the NHS, the NIHR or the Department of Health.

Footnotes

Contributors: GW-J contributed to the design of the study, reviewing papers, interpreting the analysis and the writing of the manuscript. JC contributed to the reviewing of papers and the writing of the manuscript. JLJ contributed to the design of the study, designed the search strategy, conducted the searches, reviewed the papers and contributed to the writing of the manuscript. OU conducted the meta-analysis and meta-regression. CJM contributed to the design of the study, interpreting the analysis and the writing of the manuscript. NG contributed to the design of the study and the writing of the manuscript. DvdW contributed to the reviewing of the papers, interpretation of the analysis and the writing of the manuscript. All authors read and reviewed the final manuscript.

Funding: This review was funded by the British Occupational Health Foundation (grant number 251EO7). GW-J is funded by a National Institute for Health Research Post-Doctoral Fellowship (PDF-2009-02-54).

Competing interests: None.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Hoy D, Bain C, Williams G, et al. A systematic review of the global prevalence of low back pain. Arthritis Rheum 2012;64:2028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hoy D, Brooks P, Blyth F, et al. The epidemiology of low back pain. Best Pract Res Cl Rh 2010;24:769–81 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mody GM, Brooks PM. Improving musculoskeletal health: global issues. Best Pract Res Cl Rh 2012;26:237–49 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bevan S, Quadrello T, McGee R, et al. Fit for work? Musculoskeletal disorders in the European workforce (2012). The Work Foundation Report

- 5.Widanarko B, Less S, Stevenson M, et al. Prevalence of work-related risk factors for reduced activities and absenteeism due to low back symptoms. Appl Ergon 2012;43:727–37 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cunningham CG, Flynn T, Blake C. Low back pain and occupation among Irish health service workers. Occup Med-C 2006;56:447–54 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Waddell G, Burton AK. Is work good for your health and well-being? London: The Stationery Office, 2006 [Google Scholar]

- 8.Waddell G. A new clinical model for the treatment of low-back pain. Spine 1987;12:632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Andersson GB. Epidemiological features of chronic low-back pain. Lancet 1999;354:581–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Anem JR, Schellart AJM, Cassidy JD, et al. Can cross country differences in return to work after chronic occupational back pain be explained? an exploratory analysis on disability policies in a six country cohort study. J Occup Rehabil 2009;19:419–26 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hestbaek L, Leboeuf-Y de C, Manniche C. Low back pain: what is the long-term course? A review of studies of general patient populations. Eur Spine J 2003;12:149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hayden JA, Côté P, Bombardier C. Evaluation of the quality of prognosis studies in systematic reviews. Ann Intern Med 2006;144:427–37 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.DerSimonian R, Laird N. Meta-analysis in clinical trials. Control Clin Trials 1986;7:177–88 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lipsey M, Wilson DB. Practical meta-analysis (applied social research methods series. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; Publications, 2001 [Google Scholar]

- 15.Higgins JP, Thompson SG. Quantifying heterogeneity in a meta-analysis. Stat Med 2002;21:1539–58 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Higgins JP, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, et al. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ 2003;327:557–60 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schwarzer G. Meta-analysis with R ‘meta’ fixed and random effects meta-analysis. Functions for tests of bias, forest and funnel plot. 2012. http://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/meta/meta.pdf

- 18.Biering-Sorensen F. A one-year prospective study of low back trouble in a general population. Dan Med Bull 1984;31:362–75 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hashemi L, Webster BS, Clancy EA. Trends in disability duration and cost of workers’ compensation low back pain claims (1988–1996). J Occup Environ Med 1998;40:1110–19 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Henschke N, Maher CG, Refshauge KMet al. Prognosis in patients with recent onset low back pain in Australian primary care: inception cohort study. BMJ 2008;337:7662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hiebert R, Skovron ML, Nordin M, et al. Work restrictions and outcome of nonspecific low back pain. Spine 2003;28:722–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rossignol M, Suissa S, Abenhaim L. The evolution of compensated occupational spinal injuries. A three year follow up study. Spine 1992;17:1043–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Soriano ER, Zingoni C, Lucco F. et al. Consultations for work related low back pain in Argentina. J Rheumatol 2002;29:1029–33 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Steenstra IA, Koopman FS, Knol DL, et al. Prognostic factors for duration of sick leave due to low-back pain in Dutch health care professionals. J Occup Rehabil 2005;15:591–605 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Troup JDG, Martin JW, Lloyd DCEF. Back pain in industry: a prospective survey. Spine 1981;6:61–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Vingard E, Mortimer M, Wiktorin Cet al. Seeking care for low back pain in the general population. A two year follow-up study: results from the MUSIC-Norrtälje study. Spine 2002;27:2159–65 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jensen JN, Karpatschof B, Labriola M, et al. Do fear-avoidance beliefs play a role on the association between low back pain and sickness absence? A prospective cohort study among female health care workers. J Occup Environ Med 2010;52:85–90 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lanier DC, Stockton P. Clinical predictors of outcome of acute episodes of low back pain. J Fam Practice 1988;27:483–9 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.McElligott J, Miscovich SJ, Fielding LP. Low back injury in industry: the value of a recovery program. Conn Med 1989;53:711–15 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nyiendo J. Disabling low back Oregon workers’ compensation claims. Part II: time loss. J Manipulative Physiol Ther 1991;14:231–9 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Peek-Asa C, McArthur DL, Kraus JF. Incidence of acute low-back injury among older workers in a cohort of material handlers. J Occup Environ Hyg 2004;1:551–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shinohara S, Okada M, Keira T, et al. Prognosis of accidental low back pain at work. Tohoku J Exp Med 1998;186:291–302 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Valat J-P, Goupille P, Rozenberg S, et al. Acute low back pain: predictive index of chronicity from a cohort of 2487 subjects. Joint Bone Spine 2000;67:456–61 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Vallfors B. Acute, subacute and chronic low back pain: clinical symptoms, absenteeism and working environment. Scand J Rehabil Med 1985;11:1–98 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Watson PJ, Main CJ, Waddell G, et al. Medically certified work loss, recurrence and costs of wage compensation for back pain: a follow-up study of the working population of Jersey. Br J Rheumatol 1998;37:82–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Holtermann A, Hansen JV, Burr H, et al. Prognostic factors for long-term sickness absence among employees with neck-shoulder and low-back pain. Scand J Work Environ Health 2010;36:34–41 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Demmelmaier I, Åsenlöf P, Lindberg P, et al. Biopsychosocial predictors of pain, disability, health care consumption, and sick leave in first-episode and long-term back pain: a longitudinal study in the general population. Int J Behav Med 2010;17:79–89 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nyman T, Grooten WJA, Wiktorin C, et al. Sickness absence and concurrent low back and neck-shoulder pain: results from the MUSIC-Norrtälje study. Eur Spine J 2007;16:631–8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Grotle M, Brox JI, Glomsrød B, et al. Prognostic factors in first-time care seekers due to acute low back pain. Eur J Pain 2007;11:290–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Schiøttz-Christensen B, Nielsen GL, Hansen , et al. Long-term prognosis of acute low back pain in patients seen in general practice: a 1-year prospective follow-up study. Fam Pract 1999;16:223–32 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wynne-Jones G, Dunn KM, Main CJ. The impact of low back pain on work: a study in primary care consulters. Eur J Pain 2008;12:180–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Alexopoulos EC, Konstantinou EC, Bakoyannis G, et al. Risk factors for sickness absence due to low back pain and prognostic factors for return to work in a cohort of shipyard workers. Eur Spine J 2008;17:1185–92 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Murtezani A, Hundozi H, Orovcanec N, et al. Low back pain predict sickness absence among power plant workers. Indian J Occup Environ Med 2010;14:49–53 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.van den Heuvel SG, Ariëns GAM, Boshuizen HC, et al. Prognostic factors related to recurrent low-back pain and sickness absence. Scand J Work Environ Health 2004;30:459–67 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Côté P, Baldwin ML, Johnson WG, et al. Patterns of sick-leave and health outcomes in injured workers with back pain. Eur Spine J 2008;17:484–93 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kapoor S, Shaw WS, Pransky G, et al. Initial patient and clinician expectations of return to work after acute onset of work-related low back pain. J Occup Environ Med 2006;48:1173–80 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Krause N, Dasinger LK, Deegan LJ, et al. Alternative approaches for measuring duration of work disability after low back injury based on administrative workers’ compensation data. Am J Ind Med 1999;35:604–18 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Oleinick A, Gluck JV, Guire KE. Factors affecting first return to work following a compensable occupational back injury. Am J Ind Med 1996;30:540–55 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Steenstra IA, Ibrahim SA, Franche R-L, et al. Validation of a risk factor-based intervention strategy model using data from the readiness for return to work cohort study. J Occup Rehab 2010;20:394–405 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tellnes G, Svendsen K-OB, Bruusgaard D, et al. Incidence of sickness certification. Scand J Prim Health 1989;7:111–17 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Coste J, Delecoeuillerie G, Cohen de Lara A, et al. Clinical course and prognostic factors in acute low back pain: an inception cohort study in primary care practice. BMJ 1994;308:577–80 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Dionne CE, Bourbonnais R, Frémont P, et al. Determinants of “return to work in good health” among workers with back pain who consult in primary care settings: a 2-year prospective study. Eur Spine J 2007;16:641–55 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Eilat-Tsanani S, Tabenkin H, Lavie I, et al. The effect of low back pain on work absenteeism among soldiers on active service. Spine 2010;35:E995–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Infante-Rivard C, Lortie M. Prognostic factors for return to work after a first compensated episode of back pain. Occup Environ Med 1996;53:488–94 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Linton SJ, Halldén K. Can we screen for problematic back pain? A screening questionnaire for predicting outcome in acute and subacute back pain. Clin J Pain 1998;14:209–15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Nordin M, Skovron ML, Hiebert R, et al. Early predictors of delayed return to work in patients with low back pain. J Musculoskelet Pain 1997;5:5–27 [Google Scholar]

- 57.Reis S, Hermoni D, Borkan JM, et al. A new look at low back complaints in primary care: a RAMBAM Israeli family practice research network study. J Fam Practice 1999;48:299–303 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Shaw WS, Pransky G, Winters T. The back disability risk questionnaire for work-related, acute back pain: prediction of unresolved problems at 3-month follow-up. J Occup Environ Med 2009;51:185–94 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Nordin M, Hiebert R, Pietrek M, et al. Association of comorbidity and outcome in episodes of nonspecific low back pain in occupational populations. J Occup Environ Med 2002;44:677–84 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Hadler NM, Carey TS, Garrett J. The influence of indemnification by workers’ compensation insurance on recovery from acute backache. Spine 1995; 20:2710–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kovacs FM, Muriel A, Sánchez MDC, et al. Fear avoidance beliefs influence duration of sick leave in Spanish low back pain patients. Spine 2007;32:1761–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Reiso H, Nygård JF, Jørgensen GS, et al. Back to work: predictors of return to work among patients with back disorders certified as sick. Spine 2003;28:1468–73 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Heitz CAM, Hilfiker R, Bachmann LM, et al. Comparison of risk factors predicting return to work between patients with subacute and chronic non-specific low back pain: systematic review. Eur Spine J 2009;18:1829–35 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Elfering A. Work-related outcome assessment instruments. Eur Spine J 2006;15;S32–43 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Hensing G. Swedish council on technology assessment in health care (SBU). Chapter 4. Methodological aspects in sickness-absence research. Scand J Public Health 2004;63:44–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Hensing G, Alexanderson K, Allebeck P, et al. How to measure sickness absence? Literature review and suggestion of five basic measures. Scand J Public Health 1998;26:133–44 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Wynne-Jones G, Buck R, Varnava A, et al. Impact on work absence and performance: what really matters? Occup Med-C 2009;59:556–62 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Stanton TR, Latimer J, Maher CG, et al. A modified Delphi approach to standardise low back pain recurrence terminology. Eur Spine J 2011;20:744–52 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Kendall NAS, Burton AK. The flags think-tank. Tackling musculoskeletal problems: a guide for clinic and workplace. London: The Stationery Office, 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 70.Shaw WW, van der Windt D, Main CJ, et al. The “Decade of the Flags” Working Group. Early patient screening and intervention to address individual-level occupational factors (“Blue Flags”) in back disability. J Occup Rehabil 2009;19:64–80 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Hill JC, Whitehurst DGT, Lewis M, et al. Comparison of stratified primary care management for low back pain with current best practice (STarT Back): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2011;378:1560–71 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.