Since the late 1990s, the food supply of the United States, Canada, and other countries has been fortified with folic acid to lower the incidence of neural tube defects (e.g., spina bifida, anencephaly). This fortification program has been highly successful in reducing both the prevalence of folate deficiency in the general population1,2 and the incidence of neural tube defects.3 The success of the fortification program, however, has created a situation of excess folic acid consumption by a significant percentage of the general population, the negative ramifications of which, if any, are as yet undetermined. Geometric mean serum folate levels have more than doubled in the US population (from ~12 to ~30 nmol/L)4 and the prevalence of folic acid supplement users with intakes above the upper tolerable intake level (>1 mg folic acid/day) has increased from ~1% to ~11%.5 Because folate deficiency and antifolate drugs are known to retard or prevent the proliferation of tumors, some have raised the question of whether excess folic acid in the food supply may promote malignant progression.6 Indeed, a recent analysis of data from the U.S. and Canada suggests that folic acid fortification may have increased the incidence of colorectal cancer by as much as 10%.7

FOLATE METABOLISM, DNA METHYLATION, AND CANCER

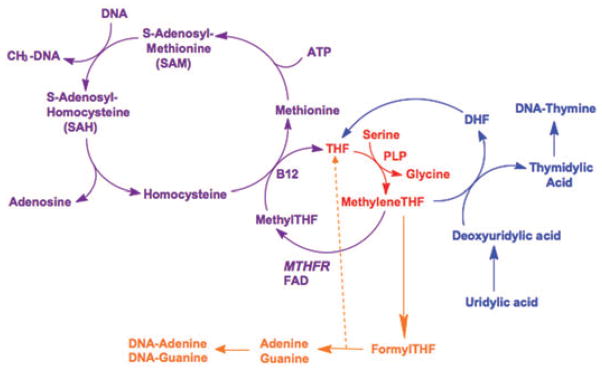

Most cancers develop through a series of stages or transformations from normal to neoplasia in situ, invasive carcinoma, and ultimately metastasis. Folate is potentially an important mediator of progressive changes in tumor cell biology, based on its central role in one-carbon metabolism (Figure 1). Folate, in the form of 5,10-methylenetetrahydrofolate, has three major biochemical fates. First, it serves as the one-carbon donor in the conversion of deoxyuridine to thymidylate, which in turn is incorporated into DNA. Folate deficiency causes inhibition of this reaction, which can result in uracil misincorporation into DNA.8 DNA repair mechanisms excise misincorporated uracil, but without newly synthesized thymidylate to replace the uracil, the DNA becomes susceptible to DNA strand breaks. DNA strand breaks may predispose cells to tumorigenic transformation and comprise the likely carcinogenic mechanism of some chemicals and toxins.8 However, it is also recognized that folate deficiency has two faces with respect to cancer (much like Janus, the Roman god of beginnings and endings, who is often depicted with two faces).9 After initiation, folate deficiency tends to retard the progression or proliferation of a tumor. This, too, is generally ascribed to the effect of folate deficiency on thymidylate synthesis (and thus DNA synthesis), which is necessary for cancer cells to proliferate. Indeed, this is the basis for the use of antifolate drugs, such as methotrexate and 5-fluorouracil, in the treatment of various cancers, including breast cancer. In addition, the second important biochemical fate of 5,10-methylenetetrahydrofolate is conversion to 10-formyltetrahydrofolate, which in turn serves as substrate for synthesis of the purines, adenine and guanine. Thus, folate deficiency may also inhibit DNA synthesis by limiting the supply of adenine and guanine.

Figure 1. Biochemical fates of methylenetetrahydrofolate.

A one-carbon unit, originating in serine, is transferred to tetrahydrofolate in a pyridoxal-5′-phosphate (vitamin B6)-dependent reaction to form methylenetetrahydrofolate (depicted in red). Methylenetetrahydrofolate then has three biochemical fates: 1) donation of the methylene group to deoxyuridylic acid to form thymidylic acid, which is then incorporated into DNA (depicted in blue); 2) conversion to formyltetrahydrofolate, which serves as substrate for the synthesis of the purines, adenine and guanine (depicted in orange); and 3) reduction by the enzyme methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase to form methyltetrahydrofolate, which in turn serves as the methyl donor in the synthesis of methionine from homocysteine. Methionine is then activated to form S-adenosylmethionine, the methyl donor in a wide variety of methylation reactions, including DNA methylation (depicted in purple). Folate status (deficiency and excess) may influence tumorigenesis by affecting thymidylate synthesis, purine synthesis, and/or DNA methylation.

Abbreviations: THF, tetrahydrofolate; DHF, dihydrofolate; MTHFR, methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase; FAD, flavin adenine dinucleotide; B12, vitamin B12 (methylcobalamin); PLP, pyridoxal-5′-phosphate.

The third important fate of 5,10-methylenetetrahydrofolate is its conversion to 5-methyltetrahydrofolate by the enzyme methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase (MTHFR). 5-Methyltetrahydrofolate then serves as the methyl donor in the conversion of homocysteine to methionine. Methionine is subsequently activated by ATP to form S-adenosylmethionine (SAM). SAM, in turn, serves as the universal methyl donor for a variety of methylation reactions, including DNA methylation. In folate deficiency, the synthesis of methionine is impaired and cellular SAM levels decrease, thus inhibiting methylation reactions, including DNA methylation. Global DNA hypomethylation has, in fact, been documented in folate deficiency.8

A hallmark of cancer cells is that their pattern of genomic DNA methylation is altered compared with normal cells. Tumor DNA is characterized by global hypomethylation, and localized regions of hypermethylation.10,11 Hypermethylation of gene promoters, catalyzed by DNA methyltransferase enzymes (DNMT), leads to repression of gene expression mediated by methylated DNA binding proteins (e.g., MeCP2 and MBD2) and associated co-repressor complexes (e.g., the NuRD and Sin3a complexes).12 Thus, aberrant DNA methylation in cancer cells may result in inappropriate under- and over-expression of specific genes, which may, in turn, promote malignant transformation and progression. Herman and Baylin13 have reviewed the potential importance of aberrant DNA methylation in tumorigenesis. They describe that the initiation and progression of cancer are influenced by both mutational and epigenetic alterations, each of which may enhance the function of oncogenes and repress the function of tumor suppressor genes. While mutations, for all practical purposes, are permanent, epigenetic alterations including DNA hypermethylation are modifiable by environmental factors, including diet and drugs. Thus, because it is required for synthesis of SAM, folate may influence tumorigenesis not only through effects on DNA synthesis, but also through epigenetic effects on gene expression.

PRECLINICAL MODELS OF BREAST CANCER

We are interested in the effect of both folate deficiency and folate excess on the natural history of breast cancer and are utilizing specific animal models to achieve this goal. Pre-clinical animal models enable experimental assessment of the influence of dietary and epigenetic factors, such as those represented by folate metabolism, on tumorigenesis. Three studies have assessed the effect of dietary folate on mammary tumorigenesis in rats induced by the chemical carcinogen, N-methyl-N-nitrosourea (MNU).14–16 These studies looked at three separate dietary conditions: 1) folate deficiency or excess initiated prior to MNU exposure and then restored to normal after MNU exposure, 2) folate deficiency or excess initiated prior to MNU exposure and maintained after exposure, and 3) folate deficiency or excess initiated after MNU exposure. The purpose of these studies was to determine if dietary folate had an effect on mammary tumor initiation, mammary tumor progression, or both. In these studies, folate deficiency appeared to have little effect on the initiation of mammary tumorigenesis by MNU, but it did slow progression. Excess dietary folate did not affect either initiation or progression. Two of the studies also assessed the effect of dietary folate on global DNA methylation in the tumors.14,15 While the tumors exhibited significant global hypomethylation compared with normal mammary tissue, there was no effect of low or high dietary folate on the extent of hypomethylation observed in the tumors. The effect of dietary folate on gene-specific methylation levels was not investigated in these studies.

The limitations of the MNU model are twofold. First, MNU is an alkylating agent that induces conversion of guanines to adenines in DNA during DNA replication.17 Such mutations lead to overexpression and activation of the H-ras oncogene, thus initiating tumorigenesis.18 The effect of MNU as a DNA akylating agent may be so strong as to override any effect of folate status (either low or high) on the initiation of the tumorigenesis process. Other mechanisms by which mammary tumorigenesis is initiated, such as erbB2 overexpression (see below), could be more susceptible to manipulation of dietary folate levels. Second, mice are more amenable to genetic manipulation than rats and less expensive to maintain. Thus, mice are a more suitable species for investigating the pathogenetic mechanisms underlying cancer.

Transgenic mice, with overexpression or activation of oncogenes implicated in human breast cancer, produce mammary carcinomas that mimic human breast cancer at both the molecular and morphological levels.19 A particularly good model is the polyomavirus middle T transgenic mouse Tg(PyVmT), which has been used as an alternate, or surrogate, for ERBB2 overexpression because the mT gene product mimics Erbb2 (and Erbb2 heterodimers) in the cell.20 Erbb2 has been implicated as a key molecule in human breast cancer21 and is overexpressed in 30–40% of human breast cancers.22 PyVmT transforms cells by disrupting signal transduction pathways through interactions with key cellular signaling proteins, such as PI3K, Shc, and Src.23,24 Tg(PyVmT) promoted by the mouse mammary tumor virus long terminal repeat (MMTV-LTR), rapidly develop mammary adenocarcinomas in all females.20 Tg (MMTV PyVmT) mice initially develop a normal mammary ductal tree,20 but then rapidly and progressively develop premalignant mammary intraepithelial neoplasias (MIN, equivalent to ductal carcinoma in situ or DCIS in humans), invasive carcinomas, and ultimately pulmonary metastases. The histomorphology of the MIN and carcinoma in these mice is comparable to human breast cancer.25

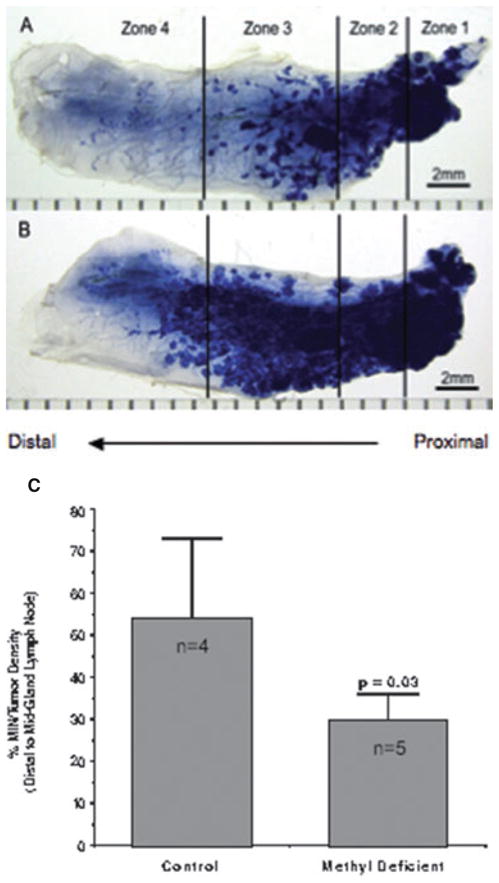

Notably, the Tg (MMTV PyVmT) mouse is responsive to dietary intervention. In a small, pilot study, we investigated the effect of a methyl-deficient diet (deficient in folate and choline and low in methionine) on the development of MIN and tumor in these mice.26 The methyl-deficient diet significantly slowed MIN growth and malignant transformation (Figure 2). We also have preliminary immunohistochemical evidence that key components of the DNA methylation machinery, including DNMT1, MeCP2, and MBD2, are highly expressed in normal ductal cells, MIN, and tumors (data not shown). The roles these epigenetic proteins play in the tumorigenic process, if any, remain to be determined.

Figure 2. Effect of dietary methyl deficiency on mammary MIN and tumor development in the PyVmT-MMTV mouse.

The images show MIN/tumor development in the #4 mammary gland at 10 weeks of age in nulliparous female heterozygous transgenic mice. Zones of the mammary gland are indicated: zone 1 represents the location of the nipple; the line between zones 2 and 3 is defined by the inguinal lymph node. A Mouse fed a methyl-deficient diet (deficient in folate and choline, and low in methionine). B Mouse fed a methyl-replete control diet. Both mice were placed on their respective diets immediately after weaning. The mammary gland from the methyl-deficient mouse shows significantly less proliferation of the breast tumors than the mammary gland from the methyl-replete mouse. C Comparison of mean % MIN/tumor density distal to the mid-gland lymph node between control (n = 4) and methyl-deficient (n = 5) mice. The methyl-deficient mice had significantly lower % MIN/tumor density than the controls after 10 weeks of their respective diets (p = 0.03 by Student’s t-test).

MOUSE MAMMARY INTRAEPITHELIAL NEOPLASIA OUTGROWTHS, A MODEL OF HUMAN DCIS

DCIS in the human breast is a heterogeneous group of morphologically characterized intraductal proliferations that are presumed to increase the risk of invasive carcinoma at the site of the lesion.27 DCIS is therefore the de facto premalignant lesion in the human breast.28 It is estimated that 25–50% of DCIS lesions will progress to invasive carcinoma, if unexcised.29,30 When DCIS is detected, current therapy involves complete excision (possibly with additional radiation and/or hormonal therapy) to eradicate the intraductal neoplasm. This therapy makes it very difficult to study DCIS progression. Nevertheless, many patients are living with DCIS undetected by screening mammography, and it often presents clinically only after progression to invasive carcinoma. Therefore, in the interests of cancer prevention, it is important to understand the factors that influence the transition from DCIS to invasive cancer. As described above, folate and DNA methylation may be important in this regard.

The developing mammary gland in Tg (MMTV PyVmT) mice does show proliferative intraductal changes,31 as seen in human DCIS, but these areas have been difficult to study as they are rapidly replaced by the growing tumors. A key refinement of the model has been the development of transplantable MIN outgrowths (MIN-Os).32–34 A small piece of a proliferating MIN lesion from a Tg (MMTV PyVmT) mouse is transplanted into a cleared mammary fat pad of a non-transgenic mouse. The MIN-O then recapitulates the proliferation, differentiation, and malignant transformation of a single MIN lesion without interference by other spatially and temporally distinct MIN lesions, as occurs in the Tg (MMTV PyVmT) mouse. In the transplantable Tg(PyVmT) MIN-O model, the proliferation of the premalignant growth begins upon transplantation. Transformation to malignancy occurs as a secondary event and is, therefore, temporally measurable. Chemoprevention and dietary interventions can be applied before transplantation, at transplantation, or at a defined time after transplantation. In addition, the MIN-O transplants progress to invasive carcinoma with predictable and consistent latencies. Effective qualitative and quantitative outcome comparisons are thus possible. MIN-O tissues and associated tumors are also accessible for comparative phenotypic and molecular analysis.

MIN-Os exhibit sequential acquisition of heterogeneous morphological and biological properties.32–34 Each MIN-O and its resulting tumors arise from stable matching clones with related gene expression profiles.34 Similarly, very little difference in gene expression profiles are observed between human DCIS and associated invasive cancers.35 Moreover, MIN-Os, like many DCIS lesions, exhibit specific dysregulation of ERBB, IGF, Ccnd1, SSP1(OPN), ETS2, VEGF, and other related pathways found in invasive breast cancer.32,36,37 Each MIN-O line has reproducible biological endpoints, such as latency and metastatic rate. These clinical outcomes, used to assess breast cancer in patients, appear to be intrinsic to the MIN-O transplantable progenitor.33 Thus, MIN-Os are a powerful and relevant preclinical model of human DCIS and tumorigenic transformation.

FOLATE, DNA METHYLATION, AND THE MIN-O MODEL: RESEARCH GOALS

Our research objective is to assess the influence of dietary folate and demethylation of DNA on the transformation of pre-malignant mammary lesions to malignancy using the MIN-O model. MIN-O lines with previously established tumor latency and incidence rates will be transplanted into cleared mammary fat pads of mice fed folate-replete (control), folate-deficient, or folate-excess diets. Additional mice receiving MIN-O transplants will be fed the control diet along with chronic administration of the DNA-demethylating agent, 5-aza-deoxycytidine (ADC). MicroPET imaging will be used to monitor MIN-O growth and tumorigenic transformation in vivo.38,39 Tumor latency and incidence, pathological characterizations, gene expression profiles, gene-specific promoter methylation, and gene targeting by methyl-CpG-binding proteins will be compared among the treatment groups.

It is expected that these studies will demonstrate roles of folate and DNA methylation in mammary tumorigenesis, and will identify specific hypermethylated genes and associated methyl-CpG-binding proteins that contribute to the transition from pre-malignant mammary lesions to malignancy. Importantly, these studies will not only focus on folate deficiency, but will also assess the effect of excess dietary folic acid on malignant transformation.

Acknowledgments

Funding. This study was financially supported by a Department of Defense Breast Cancer Research Program Synergy Grant (BC063550), the National Cancer Institute (R21 CA116409-01A2), and an American Cancer Society Research Scholar Grant (RSG CNE-107391).

Footnotes

Declaration of interest. The authors have no relevant interests to declare.

Contributor Information

Joshua W. Miller, Department of Medical Pathology and Laboratory Medicine, University of California, Davis, School of Medicine, Sacramento, California, USA

Alexander D. Borowsky, Department of Medical Pathology and Laboratory Medicine, University of California, Davis, School of Medicine, Sacramento, California, USA. Center for Comparative Medicine, University of California, Davis, Schools of Medicine and Veterinary Medicine, Davis, California, USA

Teresa C. Marple, Center for Comparative Medicine, University of California, Davis, Schools of Medicine and Veterinary Medicine, Davis, California, USA

Erik T. McGoldrick, Center for Comparative Medicine, University of California, Davis, Schools of Medicine and Veterinary Medicine, Davis, California, USA

Lisa Dillard-Telm, Center for Comparative Medicine, University of California, Davis, Schools of Medicine and Veterinary Medicine, Davis, California, USA.

Lawrence JT Young, Center for Comparative Medicine, University of California, Davis, Schools of Medicine and Veterinary Medicine, Davis, California, USA.

Ralph Green, Department of Medical Pathology and Laboratory Medicine, University of California, Davis, School of Medicine, Sacramento, California, USA.

References

- 1.Jacques PF, Selhub J, Bostom AG, Wilson PW, Rosenberg IH. The effect of folic acid fortification on plasma folate and total homocysteine concentrations. N Engl J Med. 1999;340:1449–1454. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199905133401901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Choumenkovitch SF, Jacques PF, Nadeau MR, Wilson PW, Rosenberg IH, Selhub J. Folic acid fortification increases red blood cell folate concentrations in the Framingham study. J Nutr. 2001;131:3277–3280. doi: 10.1093/jn/131.12.3277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Honein MA, Paulozzi LJ, Mathews TJ, Erickson JD, Wong LYC. Impact of folic acid fortification of the US food supply on the occurrence of neural tube defects. JAMA. 2001;285:2981–2986. doi: 10.1001/jama.285.23.2981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ganji V, Kafai MR. Trends in serum folate, RBC folate, and circulating total homocysteine concentrations in the United States: analysis of data from National Health and Nutrition Examination surveys, 1988–1994, 1999–2000, and 2001–2002. J Nutr. 2006;136:153–158. doi: 10.1093/jn/136.1.153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Choumenkovitch SF, Selhub J, Wilson PWF, Rader JI, Rosenberg IH, Jacques PF. Folic acid intake from fortification in United States exceeds predictions. J Nutr. 2002;132:2792–2798. doi: 10.1093/jn/132.9.2792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kim YI. Will mandatory folic acid fortification prevent or promote cancer? Am J Clin Nutr. 2004;80:1123–1128. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/80.5.1123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mason JB, Dickstein A, Jacques PF, et al. A temporal association between folic acid fortification and an increase in colorectal cancer rates may be illuminating important biological principles: a hypothesis. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2007;16:1325–1329. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-07-0329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.James SJ, Pogribny IP, Pogribna M, Miller BJ, Jernigan S, Melnyk S. Mechanisms of DNA damage, DNA hypomethylation, and tumor progression in the folate/methyl-deficient rat model of hepatocarcinogenesis. J Nutr. 2003;133(Suppl):S3740–S3747. doi: 10.1093/jn/133.11.3740S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kim YI. Folate, colorectal carcinogenesis, and DNA methylation: lessons from animal studies. Environ Mol Mutagen. 2004;44:10–25. doi: 10.1002/em.20025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jones PA, Laird PW. Cancer epigenetics comes of age. Nat Genet. 1999;21:163–167. doi: 10.1038/5947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Herman JG. Hypermethylation of tumor suppressor genes in cancer. Semin Cancer Biol. 1999;9:359–367. doi: 10.1006/scbi.1999.0138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Li E, Bird A. DNA methylation in mammals. In: Allis CD, Jenuwein T, Reinberg D, editors. Epigenetics. Cold Spring Harbor, NY: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 2007. pp. 341–356. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Herman JG, Baylin SB. Gene silencing in cancer in association with promoter hypermethylation. N Engl J Med. 2003;349:2042–2054. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra023075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Baggott JE, Vaughn WH, Juliana MM, Eto I, Krumdieck CL, Grubbs CJ. Effects of folate deficiency and supplementation on methylnitrosourea-induced rat mammary tumors. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1992;84:1740–1744. doi: 10.1093/jnci/84.22.1740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kotsopoulos J, Sohn K-J, Martin R, et al. Dietary folate deficiency suppresses N-methyl-N-nitrosourea-induced mammary tumorigenesis in rats. Carcinogenesis. 2003;24:937–944. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgg036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kotsopoulos J, Medline A, Renlund R, et al. Effects of dietary folate on the development and progression of mammary tumors in rats. Carcinogenesis. 2005;26:1603–1612. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgi117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Richardson KK, Richardson FC, Crosby RM, Swenberg JA, Skopek TR. DNA base changes and alkylation following in vivo exposure of Escherichia coli to N-methyl-N-nitrosourea or N-ethyl-N-nitrosourea. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1987;84:344–348. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.2.344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zarbl H, Sukumar S, Arthur AV, Martin-Zanca D, Barbacid M. Direct mutagenesis of Ha-ras-1 oncogenes by N-nitroso-N-methylurea during initiation of mammary carcinogenesis in rats. Nature. 1985;315:382–385. doi: 10.1038/315382a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cardiff RD, Wagner U, Hennighausen L. Mammary cancer in humans and mice: a tutorial for comparative pathology. Vet Pathol. 2001;38:357–358. doi: 10.1354/vp.38-4-357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Guy CT, Cardiff RD, Muller WJ. Induction of mammary tumors by expression of polyomavirus middle T oncogene: a transgenic mouse model for metastatic disease. Mol Cell Biol. 1992;12:954–961. doi: 10.1128/mcb.12.3.954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Muller WJ, Ho J, Siegel PM. Oncogenic activation of Neu/ErbB-2 in a transgenic mouse model for breast cancer. Biochem Soc Symp. 1998;63:149–157. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Barnes DM, Bartkova J, Camplejohn RS, Gullick WJ, Smith PJ, Millis RR. Overexpression of the c-erbB-2 oncoprotein: why does this occur more frequently in ductal carcinoma in situ than in invasive mammary carcinoma and is this of prognostic significance? Eur J Cancer. 1992;28:644–648. doi: 10.1016/s0959-8049(05)80117-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cheng AM, Saxton TM, Sakai R, et al. Mammalian Grb2 regulates multiple steps in embryonic development and malignant transformation. Cell. 1998;95:793–803. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81702-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Markland W, Cheng SH, Oostra BA, Smith AE. In vitro mutagenesis of the putative membrane-binding domain of polyomavirus middle-T antigen. J Virol. 1986;59:82–89. doi: 10.1128/jvi.59.1.82-89.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cardiff RD, Munn RJ. The histopathology of transgenes and knockouts in the mammary gland. In: Heppner G, editor. Advances in Oncobiology. Greenwich, CT: JAI Press Inc; 1998. pp. 177–202. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Miller JW, Borowsky AD, McGoldrick ET, Green R. Methyl deficiency slows the proliferation of breast tumors in FVB polyoma middle T (PyV-mT) transgenic mice. FASEB J. 2005;19:A420–A421. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sanders ME, Schuyler PA, Dupont WD, Page DL. The natural history of low-grade ductal carcinoma in situ of the breast in women treated by biopsy only revealed over 30 years of long-term follow-up. Cancer. 2005;103:2481–2484. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Simpson JF, Page DL. The role of pathology in premalignancy and as a guide for treatment and prognosis in breast cancer. Semin Oncol. 1996;23:428–435. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fonseca R, Hartmann LC, Petersen IA, Donohue JH, Crotty TB, Gisvold JJ. Ductal carcinoma in situ of the breast. Ann Intern Med. 1997;127:1013–1022. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-127-11-199712010-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lagios MD, Westdahl PR, Margolin FR, Rose MR. Duct carcinoma in situ. Relationship of extent of noninvasive disease to the frequency of occult invasion, multicentricity, lymph node metastases, and short-term treatment failures. Cancer. 1982;50:1309–1314. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19821001)50:7<1309::aid-cncr2820500716>3.0.co;2-#. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cardiff RD. The biology of mammary transgenes: five rules. J Mammary Gland Biol Neoplasia. 1996;1:61–73. doi: 10.1007/BF02096303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Maglione JE, Moghanaki D, Young LJ, et al. Transgenic polyoma middle-T mice model premalignant mammary disease. Cancer Res. 2001;61:8298–8305. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Maglione JE, McGoldrick ET, Young LJ, et al. Polyomavirus middle T-induced mammary intraepithelial neoplasi outgrowths: single origin, divergent evolution, and multiple outcomes. Mol Cancer Ther. 2004;3:941–953. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Namba R, Maglione JE, Young LJ, et al. Molecular characterization of the transition to malignancy in a genetically engineered mouse-based model of ductal carcinoma in situ. Mol Cancer Res. 2004;2:453–463. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ma XJ, Salunga R, Tuggle JT, et al. Gene expression profiles of human breast cancer progression. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2003;100:5974–5979. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0931261100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Borowsky AD, Namba R, Young LJ, et al. Syngeneic mouse mammary carcinoma cell lines: two closely related cell lines with divergent metastatic behavior. Clin Exp Metastasis. 2005;22:47–59. doi: 10.1007/s10585-005-2908-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Qui TH, Chandramouli GV, Hunter KW, Alkharouf NW, Green JE, Liu ET. Global expression profiling identifies signatures of tumor virulence in MMTV-PyMT-transgenic mice: correlation to human disease. Cancer Res. 2004;64:5973–5981. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-0242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Namba R, Young LJ, Abbey CK, et al. Rapamycin inhibits growth of premalignant and malignant mammary lesions in a mouse model of DCIS. Clin Cancer Res. 2006;12:2613–2621. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-2170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Abbey CK, Borowsky AD, McGoldrick ET, et al. In vivo positron-emission tomography imaging of progression and transformation in a mouse model of mammary neoplasia. PNAS. 2004;101:11438–11443. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0404396101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]