Abstract

The use of early corticosteroid withdrawal (ECSW) protocols after kidney transplantation has become common, but the effects on fracture risk and bone quality are unclear. We enrolled 47 first-time adult transplant recipients managed with ECSW into a 1-year study to evaluate changes in bone mass, microarchitecture, biomechanical competence, and remodeling with dual energy x-ray absorptiometry (DXA), high-resolution peripheral quantitative computed tomography (HRpQCT), parathyroid hormone (PTH) levels, and bone turnover markers obtained at baseline and 3, 6, and 12 months post-transplantation. Compared with baseline, 12-month areal bone mineral density by DXA did not change significantly at the spine and hip, but it declined significantly at the 1/3 and ultradistal radii (2.2% and 2.9%, respectively; both P<0.001). HRpQCT of the distal radius revealed declines in cortical area, density, and thickness (3.9%, 2.1%, and 3.1%, respectively; all P<0.001), trabecular density (4.4%; P<0.001), and stiffness and failure load (3.1% and 3.5%, respectively; both P<0.05). Findings were similar at the tibia. Increasing severity of hyperparathyroidism was associated with increased cortical losses. However, loss of trabecular bone and bone strength were most severe at the lowest and highest PTH levels. In summary, ECSW was associated with preservation of bone mineral density at the central skeleton; however, it was also associated with progressive declines in cortical and trabecular bone density at the peripheral skeleton. Cortical decreases related directly to PTH levels, whereas the relationship between PTH and trabecular bone decreases was bimodal. Studies are needed to determine whether pharmacologic agents that suppress PTH will prevent cortical and trabecular losses and post-transplant fractures.

The skeletal effects of kidney transplantation are not completely understood. One of the most devastating complications of kidney transplantation is fracture. One quarter of recipients will fracture within the first 5 years of transplantation.1 Hip fracture risk is 34% higher than for patients on dialysis,2 and hip and spine fracture risks are more than 4- and 23-fold higher, respectively,3,4 than for the general population. After hip fracture, mortality risk is 60% higher than in other kidney transplant recipients without fracture.3 Traditionally, it was thought that the corticosteroids included in immunosuppressive protocols were one of the main risk factors for post-transplant fractures.4–8 Such regimens are associated with 2%–10% declines in bone mineral density (BMD) at trabecular-rich sites, such as the spine and hip, during the first 6–12 months after transplantation.5,6,9 Thus, it was expected that newer early corticosteroid withdrawal (ECSW) immunosuppressive protocols would protect against bone loss and fractures.

Since 2000, ECSW regimens have been rapidly implemented in over one third of transplantation programs across the United States.10,11 Several trials suggested that they are associated with a stabilization of or an increase in areal BMD at the spine and hip.12–14 However, recent data suggest that management with ECSW may result in only minimal15 or no16–18 protection against fractures. These studies suggest that our understanding of fracture pathogenesis after transplantation is incomplete, that fracture risk with ECSW may be independent of changes in areal BMD measured at the spine and hip, and that ECSW may be associated with abnormalities in bone quality that are not detected by dual energy x-ray absorptiometry (DXA).

High-resolution peripheral quantitative computed tomography (HRpQCT; XtremeCT; Scanco Medical AG; 82-μm voxel size) is a novel imaging method that separately quantifies cortical and trabecular geometry, density, and microarchitecture, and finite element analysis (FEA), a computational estimate of bone strength that correlates highly with ex vivo strength testing, can be applied to HRpQCT datasets.19,20 Our group has used HRpQCT, calciotropic hormones, and bone turnover markers (BTMs) to evaluate the mechanisms of increased skeletal fragility21,22 and the pathogenesis of bone loss23 in patients with CKD. We showed that CKD patients with fractures have lower cortical and trabecular volumetric BMDs, thinner cortices, and abnormal trabecular microarchitecture at the distal radius and tibia. We also showed that, over time, cortical losses predominate, driven by increased levels of parathyroid hormone (PTH). Longitudinal studies investigating pathobiologic mechanisms of increased skeletal fragility in kidney transplant recipients managed with ECSW have not been conducted. Therefore, we performed a 12-month prospective study in first-time recipients managed with an ECSW protocol. We hypothesized that over the first 1 year after transplantation, management with ECSW would be associated with stable areal BMD measured by DXA but that HRpQCT would shed light on potential microarchitectural deterioration not detected by DXA.

Results

Cohort Characteristics

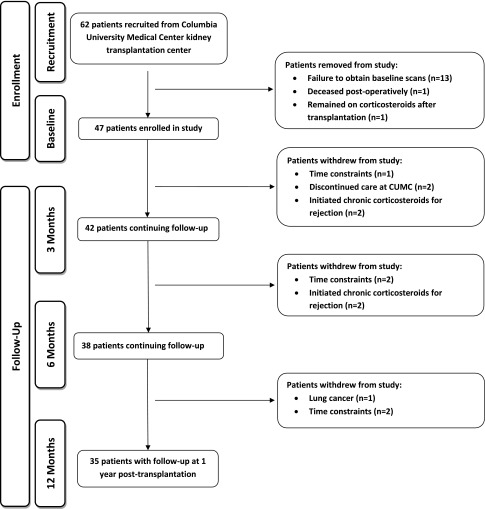

Figure 1 describes the study flow and reasons for attrition. Forty-seven patients completed baseline enrollment procedures, and patients were censored if they initiated chronic corticosteroids (n=5). Demographic characteristics of 47 patients with baseline data are presented in Table 1. Mean age was 50.5±13.7 years, 70% of patients were men, 81% of patients received a living donor allograft, 49% of patients were on dialysis pretransplantation, and median T scores were in the normal range.

Figure 1.

Flow-chart of patients who enrolled, dropped out, and completed the study.

Table 1.

Baseline cohort characteristics of enrolled kidney transplantation recipients

| Variable | n=47 |

|---|---|

| Age at transplantation (yr±SD) | 50.5±13.7 |

| Age group (yr), N (%) | |

| 18–55 | 20 (43) |

| >55 | 27 (57) |

| Sex, N (%) | |

| Men | 33 (70) |

| Women | 14 (30) |

| Race/ethnicity, N (%) | |

| White | 33 (70) |

| Hispanic | 9 (19) |

| Body mass index (kg/m2; mean±SD) | 28.3±6.1 |

| Body mass index group, N (%) | |

| 18.5–24.9 | 17 (36) |

| 25–29.9 | 14 (30) |

| Over 30 | 16 (34) |

| Type of donor, N (%) | |

| Living | 38 (81) |

| Deceased | 9 (19) |

| Pretransplantation dialysis, N (%) | 23 (49) |

| Cause of ESRD, N (%) | |

| Diabetes/hypertension | 14 (30) |

| Glomerular disease | 23 (49) |

| Other | 10 (21) |

| Baseline T scores by DXA, median (interquartile range) | |

| Lumbar spine | 0.4 (−1.0, 1.3) |

| Total hip | −0.3 (−1.1, 0.4) |

| Femoral neck | −0.8 (−1.3, −0.3) |

| 1/3 Radius | 0.04 (−0.6, 1.3) |

| Ultradistal radius | −0.4 (−1.1, 0.5) |

Longitudinal Changes in Kidney Function and Biochemistries

Baseline and follow-up levels of kidney function (GFR and serum creatinine) and concentrations of calcium, phosphorus, PTH, and BTMs are presented in Table 2. At 3 months, mean GFR was 45 ml/min per 1.73 m2 and remained relatively stable thereafter. Levels of calcium increased and phosphorus decreased after transplantation, and both levels remained within the normal reference range thereafter. Before transplantation, levels of PTH, osteocalcin, and C-terminal telopeptides of type I collagen (CTX) were greater than the reference range. At 3 months, PTH, osteocalcin, and CTX decreased by 36±58%, 44±46%, and 32±48%, respectively, and bone-specific alkaline phosphatase (BSAP) and procollagen of type 1 N-terminal propeptide (P1NP) increased by 66±79% and 58±78%, respectively. All biochemistries remained either above or within the upper levels of the reference range thereafter, and differences in levels among post-transplantation time points were not significant. Thus, correlation and regression analyses were conducted with time-averaged post-transplantation levels.

Table 2.

Kidney function and biochemical markers of bone metabolism at enrollment before transplantation and over 12 months after transplantation

| Variable | Enrollment | 3 Months | 6 Months | 12 Months |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | 47 | 37 | 35 | 33 |

| Kidney function (mean±SD) | ||||

| GFR (ml/min per 1.73 m2) | 13±3.9 | 45±17a | 49±15a | 49±17a |

| Serum creatinine (mg/dl) | 5.8±2.0 | 1.8±0.7a | 1.5±0.5a | 1.5±0.4a |

| Calcium (mg/dl) | 9.0±0.8 | 9.7±0.6a | 9.6±0.6a | 9.6±0.6a |

| Phosphorus (mg/dl) | 3.8±1.6 | 3.0±0.7 | 3.1±0.6b | 2.6±1.1a |

| Biochemical markers (mean±SD) | ||||

| PTH (reference range=15–65 pg/ml) | 256±148 | 102±46a | 95±51a | 99±54a |

| Bone-specific alkaline phosphatase (reference range=15–65 U/L) | 30.6±16.7 | 47.8±26.6a | 49.3±25.8a | 44.2±17.0 |

| Osteocalcin (reference range=9.7–35.1 ng/ml) | 165±132 | 57±40a | 59±44a | 51±30a |

| P1NP (reference range=20–100 µl/L) | 78±50 | 102±68c | 99±73c | 82±56 |

| CTX (reference range=0.162–0.573 U/L) | 1.832±1.086 | 0.831±0.580a | 0.807±0.734a | 0.760±0.533a |

Reference ranges are for premenopausal women.

P<0.001 versus baseline.

P<0.05 versus baseline.

P<0.01 versus baseline.

Longitudinal Changes in Bone Mass and Microstructure

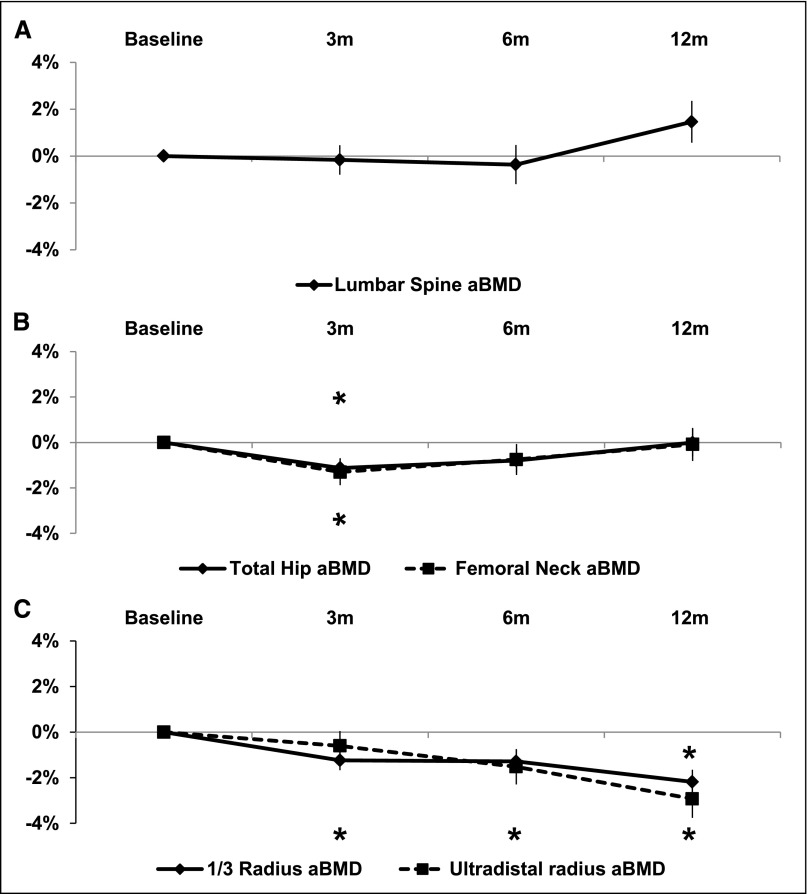

Univariate mixed linear regression models adjusted for baseline measures were used to assess changes in bone geometry, mass, and microarchitecture over the first 12 months after transplantation. By DXA (Figure 2), lumbar spine BMD did not change significantly over the first post-transplant year. There were small but significant and transient losses at the total hip (1.1±0.4%; P=0.01) and femoral neck (1.3±0.6%; P=0.03) at 3 months that recovered to levels not significantly different from baseline at 6 and 12 months. In contrast, at the forearm, BMD declined linearly, and by 12 months after transplantation, it was 2.2±0.5% (P<0.001) and 2.9±0.8% (P<0.001) below baseline at the 1/3 and ultradistal radii, respectively.

Figure 2.

Twelve-month changes in areal BMD (aBMD) measured by DXA at the central and peripheral skeleton. Data is represented as change±SEM in aBMD for patients on ECSW at the: (A) lumbar spine, (B) hip, and (C) forearm. *P<0.05.

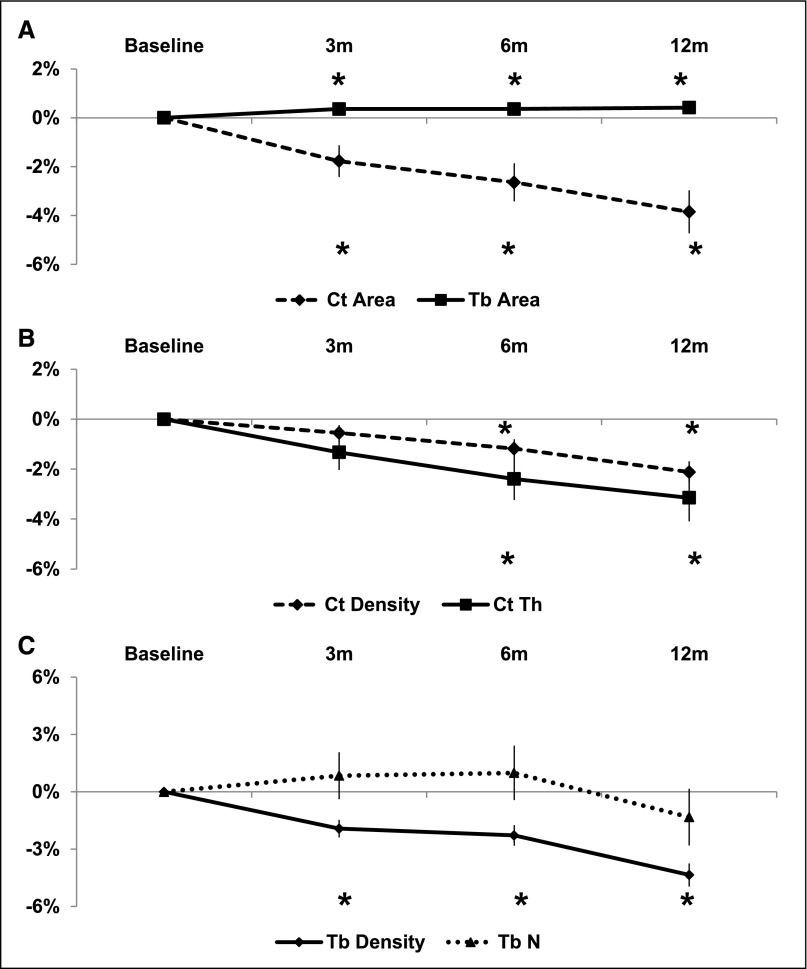

By HRpQCT at the distal radius (Figure 3), there was deterioration in both cortical and trabecular compartments. After 12 months, there were highly significant and linear decreases in cortical area (3.9±0.9%), thickness (3.1±0.9%), and density (2.1±0.4%; all P<0.001). Trabecular area increased slightly but significantly (0.4±0.2%; P<0.05), and trabecular density decreased significantly (4.4±0.6%; P<0.001). Changes in trabecular number and heterogeneity were not significant. At the tibia, deterioration was mainly limited to the cortical compartment. Over 12 months, there were significant and linear decreases in cortical area (2.7±0.8%; P<0.001), thickness (1.9±0.8%; P=0.05), and density (2.4±0.4%; P<0.001), and trabecular area increased (0.3±0.1%; P<0.001). At 3 months, there was a significant 1.3±0.4% (P<0.01) decline in trabecular density that recovered to a level not significantly different from baseline at 6 and 12 months. There were no significant changes in trabecular number or heterogeneity.

Figure 3.

Twelve-month changes in radius cortical and trabecular measures obtained by HRpQCT. Data is represented as change±SEM in radius: (A) cortical (Ct) and trabecular (Tb) area, (B) cortical density (Ct Density) and thickness (Ct Th), and (C) trabecular density (Tb Density) and number (Tb N). *P<0.05.

Predictors of Post-Transplantation Bone Loss

We identified risk factors for bone loss. By DXA, each 10-year increase in age at transplantation predicted a 0.5±0.2% (P<0.01) greater decline in 1/3 radius areal BMD. By HRpQCT at the radius, women had a 1.3±0.6% (P<0.05) greater decline in cortical density than men, and each 10-year increase in age at transplantation predicted a 0.6±0.02% (P<0.05) greater decline in trabecular density. At the tibia, women had a 1.6±0.6% (P<0.05) greater decline in trabecular density than men. Each 1 g corticosteroid administered temporarily for acute rejections was associated with a 1.1±0.4% (P<0.01) and 1.4±0.3% (P<0.001) decline in trabecular density at the radius and tibia, respectively. Time-averaged post-transplantation GFR did not predict changes by DXA or HRpQCT.

We next examined whether the changes in bone geometry, density, and microarchitecture detected in univariate analyses were predicted independently by time-averaged post-transplantation levels of BTMs. Relationships between changes in bone density and biochemical measures are reported with the following cutoffs: BSAP per 5 U/L, osteocalcin per 5 ng/ml, P1NP per 10 µg/L, and CTX per 0.05 ng/ml.23 All models were adjusted for sex and age at transplantation, and trabecular models were also adjusted for cumulative dose of corticosteroids. By DXA, there were no significant associations between BTMs and bone loss. By HRpQCT at the distal radius, there were no significant associations between pretransplantation BTMs and cortical measures. In contrast, higher levels of post-transplantation BSAP, osteocalcin, P1NP, and CTX predicted significant declines in cortical area, density, and thickness (Table 3). At the tibia, relationships between changes in cortical geometry and density and formation markers were similar to but less robust than those changes at the radius; relationships with the resorption marker were not significant (data not shown).

Table 3.

Relationships between post-transplantation levels of bone formation and resorption markers on radius cortical and trabecular bone

| BTM | Cortical Area | Cortical Density | Cortical Thickness | Trabecular Area | Trabecular Density | Stiffness | Load Failure |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BSAP | −4.5±1.6; 0.007 | −2.2±0.9; 0.01 | −4.9±1.7; 0.006 | 0.4±0.4; 0.40 | −0.3±0.8; 0.70 | −1.1±3.6; 0.80 | −0.2±1.9; 0.90 |

| Osteocalcin | −2.0±1.2; 0.10 | −1.4±0.6; 0.04 | −2.2±1.2; 0.08 | 0.2±0.3; 0.60 | 0.5±0.7; 0.50 | −4.2±1.8; 0.02 | −4.4±1.9; 0.03 |

| P1NP | −3.1±1.2; 0.02 | −2.1±0.7; 0.003 | −3.1±1.3; 0.02 | 0.3±0.3; 0.30 | −0.5±0.7; 0.50 | −3.6±2.1; 0.09 | −2.7±2.2; 0.20 |

| CTX | −2.6±1.1; 0.02 | −1.6±0.6; 0.009 | −2.9±1.1; 0.01 | 0.2±0.3; 0.40 | 0.1±0.6; 0.80 | −4.0±1.6; 0.02 | −4.2±1.7; 0.02 |

All models are adjusted for age at transplantation and sex, and trabecular models are also adjusted for cumulative corticosteroid dose. Data are represented as β-coefficient±SEM; P value.

PTH modulates both remodeling rates and bone loss; therefore, we investigated relationships between PTH and BTMs and changes in bone. Adjusted for GFR, there were significant correlations between post-transplantation levels of PTH and BSAP (0.48; P<0.01), osteocalcin (0.37; P<0.05), P1NP (0.33; P<0.05), and CTX (0.33; P<0.05). As for analyses of BTMs, regression models were adjusted for sex and age, and trabecular models were also adjusted for cumulative corticosteroid dose. By DXA, there were no associations between pretransplantation PTH and areal BMD. In contrast, each 10-pg/ml higher post-transplantation PTH level was associated with a 1.9±0.9% (P=0.05) and 2.3±0.8% (P<0.01) decrease in areal BMD at the total hip and femoral neck, respectively. By HRpQCT at the distal radius, there were no associations between pretransplantation PTH and cortical measurements. In contrast, associations between post-transplantation levels of PTH and declines in cortical measures were linear (Figure 4). Higher time-averaged levels of PTH predicted significant declines in cortical area (2.9±1.4%; P<0.05) and thickness (3.1±1.5%; P<0.05) but not density. At the tibia, relationships between PTH and changes in cortical geometry and mass were not significant (data not shown).

Figure 4.

Scatter plots representing relationships between time-averaged post-transplantation PTH and 12-month changes in: (A) radius cortical area and (B) thickness. Horizontal reference line demarcates the lack of bone loss based on our laboratory’s precision for each bone structural parameter.

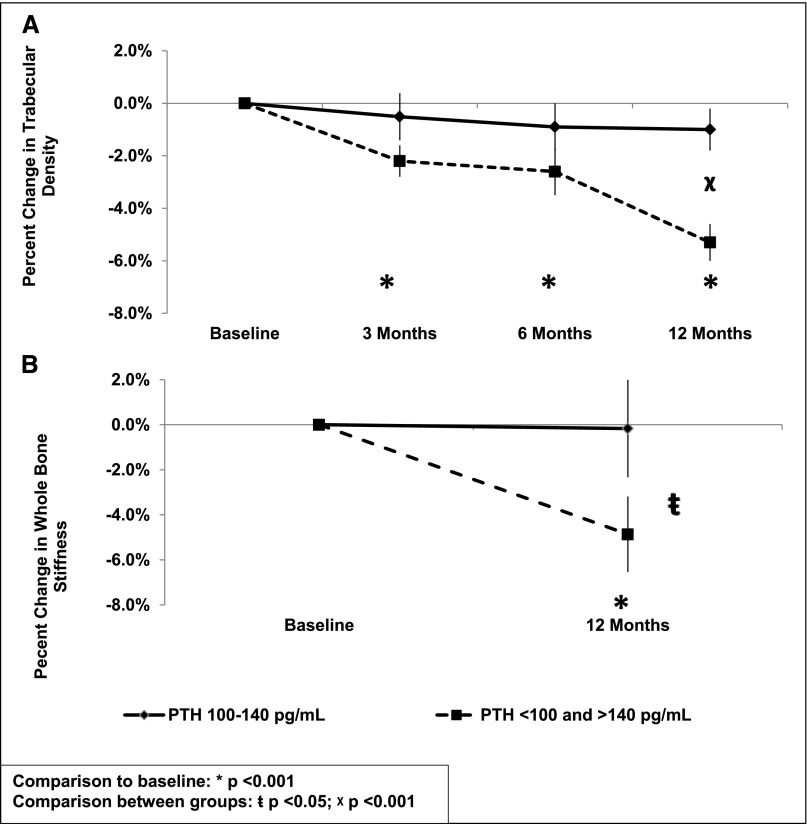

Effects of PTH on radius trabecular bone differed from effects of PTH on cortical bone. Each unit increase in pretransplantation PTH predicted a 2.1±1.0% (P<0.05) decline in trabecular number. In contrast, relationships between post-transplantation PTH and trabecular measures were bimodal (Figure 5). Levels <100 or >140 pg/ml were associated with significantly more severe decreases in trabecular density (1.7±0.7%; P<0.03) than PTH levels between 100 and 140 pg/ml. At the tibia, relationships between PTH and changes in trabecular bone were not significant (data not shown).

Figure 5.

Twelve-month decreases in trabecular density and whole bone stiffness stratified by level of PTH. The effect of time-averaged post-transplantation PTH levels between 100 and 140 pg/ml compared with <100 and >140 pg/ml on 12-month change in (A) radius trabecular density and (B) whole-bone stiffness. Comparison with baseline: *P<0.001. Comparison between groups: ŧP<0.05; χP<0.001.

Bone Biomechanical Competence after Kidney Transplantation

Whole-bone stiffness and failure load integrate changes in cortical and trabecular compartments and provide biomechanical estimates that correlate with bone strength. Twelve months after kidney transplantation, whole-bone stiffness and failure load decreased significantly (3.1±1.4% and 3.5±1.4%, respectively; both P<0.05) at the radius but not the tibia. Post-transplant kidney function and cumulative corticosteroid dose were not associated with significant changes in stiffness and failure load. Multivariate models showed effects of post-transplantation levels of BTMs and PTH on radius stiffness and failure load. For BTMs (Table 3), effects were linear, and increases in BTMs were associated with decreases in stiffness and failure load. Similar to trabecular bone, PTH effects were bimodal. Levels<100 or >140 pg/ml were associated with significantly more rapid decreases in stiffness (4.2±1.8%; P<0.05) and failure load (4.4±2.0%; P<0.05) than levels between 100 and 140 pg/ml.

Discussion

As we hypothesized, ECSW was associated with stable areal BMD by DXA at the spine and hip. However, there were paradoxical effects at the peripheral skeleton, with significant declines in areal BMD at the forearm. By HRpQCT, we determined that peripheral skeletal losses were caused by deterioration of cortical and trabecular geometry, density, and microarchitecture, which resulted in loss of bone strength. Finally, we found that effects of PTH on cortical and trabecular bone differed. Cortical losses were linear and driven by greater severity of post-transplantation hyperparathyroidism. However, for trabecular bone and bone biomechanical competence, the effects of PTH levels were bimodal: more deterioration occurred at the lowest and highest levels of PTH. These novel data are the first to describe mechanisms of increased skeletal fragility in kidney transplant recipients managed with ECSW.

The only other study to investigate the evolution of cortical and trabecular microarchitecture after kidney transplantation used micromagnetic resonance imaging and found that cortical, trabecular, and whole-bone stiffness significantly decreased over the first 6 months after kidney transplantation.24 However, recipients were managed with a traditional corticosteroid-based regimen, significant declines in cortical and trabecular density and cortical thickness were not detected, and biochemical data were not reported. Corticosteroids have marked inhibitory effects on osteoblast function,25–28 have moderate stimulatory effects on osteoclast function,29,30 induce hypogonadotrophic hypogonadism and myopathy, and reduce production of IGF and IGF binding proteins.31 Thus, it was expected that management of post-transplantation immunosuppression without corticosteroids would significantly reduce rates of bone loss and fractures.

There are no randomized trials designed a priori to determine whether ECSW regimens result in fewer fractures. The secondary analyses conducted to date raise concerns about the preconception that ECSW regimens would substantially lower fracture risk.15–18 Trials by Woodle et al.17 and Rizzari et al.16 found no difference in fracture rates. However, fractures were a secondary outcome, and spine fractures, among the most common types of post-transplant fractures,4 were not ascertained. A retrospective study by Edwards et al.18 found that corticosteroid withdrawal did not result in a fracture reduction benefit. However, the corticosteroid withdrawal regimens in the study were not reflective of current ECSW protocols, and the patient population was not reflective of most patients managed with ECSW: patients were managed with up to 6 months of corticosteroids, had type 1 diabetes, and received simultaneous kidney–pancreas transplantation. Using the US Renal Data System (USRDS), we found that discharge from the hospital without corticosteroids was associated with a 1.6% reduction in absolute fracture risk. We also noted that there was no significant difference in risk during the first 2 years after transplantation and that other risk factors for fracture (age, pretransplant diabetes, and fracture) had more profound effects on fracture incidence than corticosteroid use.15 However, because we were only able to ascertain fractures that resulted in a hospital admission and could not assess vertebral fractures, our study underestimated fracture risk. These findings suggest that the pathogenesis and epidemiology of ECSW-associated fractures remain poorly defined, despite more than a decade of experience with these regimens.

Most data concerning skeletal effects of corticosteroid withdrawal regimens have focused on the central skeleton. Aroldi et al.14 evaluated 18-month changes in lumbar spine BMD in 13 patients managed with ECSW compared with 40 patients managed with corticosteroid-based regimens. At 18 months, ECSW was associated with a significant 5.8% increase in spine BMD compared with an 8% decrease in patients managed with corticosteroids. In 261 transplant recipients randomized to corticosteroid withdrawal at either 3 days or 4 months post-transplantation, ter Meulen et al.12 evaluated changes in lumbar spine and femoral neck BMD during the first post-transplant year. At 3 months, spine BMD decreased 1.3% in patients randomized to corticosteroid withdrawal at 3 days versus 2.3% in patients randomized to withdrawal at 4 months. At 12 months, spine BMD recovered to levels not significantly different from baseline in both groups. Similarly, at the femoral neck, BMD decreased significantly by 1.4% in both groups at 3 months and recovered to levels not different from baseline in both groups at 12 months. In a subset of patients, the study by ter Meulen et al.13 used quantitative ultrasound to measure the impact of 3 days versus 4 months of corticosteroids at the calcaneus, a peripheral skeletal site comprised mainly of trabecular bone. Broadband ultrasound attenuation, a measure of bone structure as well as mass, declined linearly over 12 months in both groups, despite increases in BMD at the central skeleton sites. Thus, similar to our findings, ter Meulen et al.13 found divergent effects of ECSW on bone mass at the central and peripheral skeleton.

Our novel findings not only expand on these studies, but they raise concerns regarding the ability of ECSW protocols to protect against fracture. They suggest that, even in the absence of long-term corticosteroids, post-transplantation hyperparathyroidism and elevated remodeling rates result in cortical and trabecular losses and decreases in bone strength at the peripheral skeleton. By 12 months, based on our HRpQCT precision estimates, the majority of patients lost cortical and trabecular density at the radius (58% and 81%, respectively) and cortical density at the tibia (75%). Significant decreases in cortical thickness and increases in trabecular area at both the radius and tibia suggest endocortical cancelization, and our regression analyses imply that persistent post-transplantation hyperparathyroidism modulates this process. We also found that PTH effects on cortical and trabecular bone differ. Higher levels of PTH were associated with the largest cortical losses. However, PTH effects on trabecular bone and bone strength were bimodal. Because more than 85% of the skeleton is comprised of cortical bone, our observations suggest that fractures will continue to be common complications of kidney transplantation, even in the absence of corticosteroids.

The current Kidney Disease Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) Guidelines for the management of bone and mineral disease after transplantation suggest that, in patients with a GFR>30 ml/min, that areal BMD should be measured in the first 3 months after transplantation if they receive corticosteroids or have risk factors for osteoporosis, like in the general population.32 The KDIGO does not provide recommendations regarding defining PTH target levels, using BTMs to guide therapies to prevent post-transplantation bone loss, or measuring BMD in patients managed without corticosteroids. Data from our group and others suggest that the KDIGO guidelines may require revisiting and modification. In recipients managed with corticosteroids, both low33 and high34–36 PTH concentrations correlated with post-transplantation bone loss by DXA, and Giannini et al.37 found that each 1-pg/ml higher increment in PTH was associated with a significant 1% increased odds of vertebral fracture. These data suggest that optimal target levels of PTH and BTMs, based on fracture outcomes, need to be defined, that measurement of areal BMD should be obtained in kidney transplant recipients (regardless of whether they are managed with corticosteroids), and that the forearm may be the best site to assess BMD in recipients managed with ECSW.

This study has limitations. Our sample size limited the number of predictors included in multivariate regression models. Our population was predominantly Caucasian. However, our USRDS report suggested that black and Asian races protect against fractures; thus, our results are applicable to the population at highest fracture risk. The lack of both post-transplantation bone loss and corticosteroids effects detected by DXA at the spine and hip should be interpreted with caution. DXA has low resolution and does not detect small changes in BMD or quantify cortical and trabecular bone separately. Moreover, measurement of areal BMD at the spine may be affected by the presence of aortic calcifications, end plate osteosclerosis, and osteoarthritis, which are common in CKD. Finally, at our institution, tacrolimus is the calcineurin inhibitor of choice, and no patients were managed with cyclosporine.

In conclusion, we found progressive deterioration of cortical and trabecular bone mass and microarchitecture and decreased bone strength in kidney transplant recipients managed with ECSW. These losses were associated with elevated levels of PTH and remodeling markers, and older patients and women were at highest risk for bone loss. These data suggest pathobiologic mechanisms that account for the higher than expected rates of fractures reported in studies of kidney transplant recipients managed without long-term corticosteroids. They support the design and implementation of a trial of PTH suppression as a fracture preventative measure in kidney transplant recipients managed with ECSW regimens.

Concise Methods

Patients

The Columbia University Medical Center (CUMC) Institutional Review Board approved this study; all patients provided written informed consent, and all data were maintained in compliance with CUMC and Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act guidelines. We recruited 62 consecutive first-time living and deceased donor kidney transplant recipients from the CUMC kidney transplantation center between September of 2009 and May of 2010. Subjects ranged between 18 and 75 years old, and all were managed with an ECSW immunosuppressive protocol. At the time of transplantation, patients received induction with 4 days of tapering methylprednisolone along with either thymoglobulin or basiliximab; corticosteroids were withdrawn by the end of postoperative day 3. Maintenance immunosuppression was with tacrolimus and mycophenolic acid. Tacrolimus was started in the perioperative period at 0.05 mg/kg every 12 hours and adjusted to levels of 8–12 ng/ml on postoperative day 2 according to the established CUMC kidney transplantation immunosuppression protocol.

All transplant recipients at CUMC are placed on ECSW immunosuppression, except those recipients either with positive cross-match antibodies or who are already taking corticosteroids at time of transplantation. Patients were excluded from this study if they had a history of prior solid organ (including prior kidney) transplantation, had malignancy, or were taking bisphosphonates, gonadal steroids, aromatase inhibitors, or anticonvulsants that induce hepatic cytochrome P450 enzymes. Patients were censored if they were started on chronic corticosteroid-based immunosuppression at any time point after transplantation. Five enrolled patients were censored because of initiation of chronic corticosteroids (Figure 1). Over the course of this study, three patients were initiated on temporary corticosteroids for single rejection episodes; these patients were not excluded from analyses.

Administration of Strategies that Alter PTH Levels

This trial was not a randomized trial; thus, parathyroidectomy and administration of bone active medications were not standardized. No patient had parathyroidectomy either before or after transplantation, and no patient received phosphorus supplementation after transplantation. Before transplantation, 3 patients were managed with calcitriol, 19 patients were managed with a vitamin D analog (paricalcitol or doxercalciferol), and 4 patients were managed with cinacalcet. At transplantation, vitamin D analogs were stopped in 16 patients, cinacalcet was stopped in all 4 patients, and calcitriol was continued. After transplantation, calcitriol was initiated in one patient, and cinacalcet was initiated in two patients for the first time and reinitiated in one patient. Because of the small number of patients initiating medications that alter PTH levels after transplantation, we were unable to assess whether they had effects on the changes reported in this investigation.

Imaging Studies

All patients underwent imaging at baseline and 3, 6, and 12 months. Areal BMD by DXA was measured at the total lumbar spine, total hip, femoral neck (FN), and nondominant 1/3 and ultradistal radii using a Hologic QDR 4500 densitometer (Hologic, Inc., Waltham, MA) in the array (fan beam) mode. In our laboratory, short-term in vivo precision is 0.68% for the spine, 1.36% for the FN, and 0.70% for the radius. T scores compared patients with young normal populations of the same race and sex provided by the manufacturer (spine and forearm) and National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey III (total hip and FN).

HRpQCT (XtremeCT; Scanco Medical, Brüttisellen, Switzerland) methods have been described in our previous studies.21–23 In brief, HRpQCT was performed at the nondominant forearm and leg unless there was previous fracture or an arteriovenous fistula or graft at the desired site, in which case the opposite limb was scanned. All scan acquisition was performed in our laboratory by a single dedicated research densitometry technologist according to the standard manufacturer’s protocols described previously.21,22 A phantom was scanned daily for quality control. To analyze the same region in the longitudinal scans, the manufacturer’s software was used to find the overlapping regions between the baseline and follow-up scans.38 It is performed by matching the cross-sectional areas of the individual slices to find the common region between the two scans. From this standard analysis, trabecular volumetric BMD (milligrams hydroxyapatite per centimeter3) is defined as the average bone density within the trabecular volume of interest. Because measurements of trabecular microstructure are limited by the resolution of HRpQCT, which approximates the width of individual trabeculae, trabecular structure is assessed using semiderived algorithms.39,40 Trabecular number is defined as the inverse of the mean spacing of the midaxes. The intraindividual distribution of separation (micrometers), a parameter that reflects the heterogeneity of the trabecular network, is also measured. In addition to the standard analysis, a validated autosegmentation method41 was applied to segment the cortical and trabecular compartments to measure cortical thickness (millimeters), and cortical BMD (milligrams hydroxyapatite per centimeter3).42,43 Cortical thickness was measured directly using a distance transform,44 and cortical BMD was defined as the average mineral density in the autosegmentation cortical bone mask. In vivo precision of HRpQCT measurements have been reported to be <1% for density measurements and <4.5% for morphologic measurements.45 In our laboratory, precision measurements are (1) radius cortical area, density, and thickness: 1.25%, 0.81%, and 1.53%, respectively; (2) radius trabecular density: 1.06%; (3) tibia cortical area, density, and thickness: 0.91%, 0.55%, and 0.91%, respectively; and (4) tibia trabecular density: 0.91% (courtesy of X. Sherry Liu, unpublished data). FEA was used to estimate whole-bone stiffness (ultimate stress; megapascals) and failure load (newtons). We simulated uniaxial compression on each radius and tibia model up to 1% strain using a homogenous Young’s modulus of 6829 MPa and Poisson’s ratio of 0.3.45 We used a custom FEA solver (FAIM, Version 6.0; Numerics88, Calgary, AB, Canada) installed on a desktop workstation (Linux Ubuntu 12.10, 2×6-core Intel Xenon, 64GB RAM) to solve the models.

Image Quality Assessment

All HRpQCT images were assessed for image quality and motion artifact before analysis, and they were graded on a scale of one (no imaging abnormalities) to five (severe abnormalities).46,47 Any image score of four or five was excluded from analyses.

Laboratory Measurements

Routine laboratory parameters were measured by Quest Diagnostics (Teterboro, NJ). Serum creatinine was determined by the Jaffe reaction, and serum calcium, phosphorus, and bicarbonate were measured by spectrophotometry. GFR was estimated based on the Modification of Diet in Renal Disease formula.48 Bone metabolic markers were measured at CUMC in a specialized research laboratory. Intact PTH, BSAP, N-midosteocalcin, P1NP, tartrate resistant acid phosphatase 5b, and CTX were measured by a Roche Elecsys 2010 analyzer (Roche Diagnostics, Indianapolis, IN). Intra- and interassay precisions are intact PTH, 1.0% and 4.4%; BSAP, 6.0% and 8.0%; osteocalcin, 0.8% and 2.9%; P1NP, 1.1% and 5.5%; and CTX, 1.1% and 5.5%.

Statistical Methods

Statistical analyses were conducted using SAS (version 9.2; SAS Institute, Cary, NC). Categorical data were compared using the chi-squared test. Continuous data were evaluated for normality before statistical testing and log-transformed when appropriate. Levels of body mass index, PTH, and BTMs did not differ significantly among the 3-, 6-, and 12-month post-transplantation time points; therefore, correlation and regression analyses were conducted with time-averaged levels for the post-transplantation measurements. Effects of PTH and BTMs on changes in bone parameters were analyzed as unit changes of PTH, 10 pg/ml; BSAP, 5 U/L; osteocalcin, 5 ng/ml; P1NP, 10 µg/L; tartrate resistant acid phosphatase 5b, 0.01 U/L; and CTX, 0.05 ng/ml.23 Spearman correlations, adjusted for kidney function, were determined for relationships between time-averaged post-transplantation levels of PTH and BTMs. Univariate mixed linear regression models adjusted for baseline measures assessed the evolution of bone geometry, mass, microarchitecture, and mechanical competence over the first 12 months of transplantation. Multivariate mixed linear regression models were used to determine predictors of changes in bone geometry, mass, microarchitecture, and mechanical competence adjusted for (1) baseline bone measures, (2) levels of pretransplantation and time-averaged post-transplantation PTH and BTMs, (3) age, and (4) sex. For trabecular models, adjustment was also made for cumulative corticosteroid dose. Although 47 patients were enrolled and followed in this investigation, 35 patients had data at both the baseline and 12-month visits. A sensitivity analysis conducted with only these 35 patients showed no material or statistical change in the assessed bone outcomes. Therefore, all 47 patients are included in our report.

Disclosures

None.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Doris Duke Charitable Foundation (to S.P.I. and L.E.N.) and a Columbia University Herbert Irving Award (to T.L.N.). Additionally, this research was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants K24 AR052665 (to E.S.) and K23 DK080139 (to T.L.N.) and National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences Grant UL1 TR000040.

Footnotes

Published online ahead of print. Publication date available at www.jasn.org.

References

- 1.Nikkel LE, Hollenbeak CS, Fox EJ, Uemura T, Ghahramani N: Risk of fractures after renal transplantation in the United States. Transplantation 87: 1846–1851, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ball AM, Gillen DL, Sherrard D, Weiss NS, Emerson SS, Seliger SL, Kestenbaum BR, Stehman-Breen C: Risk of hip fracture among dialysis and renal transplant recipients. JAMA 288: 3014–3018, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Abbott KC, Oglesby RJ, Hypolite IO, Kirk AD, Ko CW, Welch PG, Agodoa LY, Duncan WE: Hospitalizations for fractures after renal transplantation in the United States. Ann Epidemiol 11: 450–457, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vautour LM, Melton LJ, 3rd, Clarke BL, Achenbach SJ, Oberg AL, McCarthy JT: Long-term fracture risk following renal transplantation: A population-based study. Osteoporos Int 15: 160–167, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Julian BA, Laskow DA, Dubovsky J, Dubovsky EV, Curtis JJ, Quarles LD: Rapid loss of vertebral mineral density after renal transplantation. N Engl J Med 325: 544–550, 1991 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Horber FF, Casez JP, Steiger U, Czerniak A, Montandon A, Jaeger P: Changes in bone mass early after kidney transplantation. J Bone Miner Res 9: 1–9, 1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Moreno A, Torregrosa JV, Pons F, Campistol JM, Martínez de Osaba MJ, Oppenheimer F: Bone mineral density after renal transplantation: Long-term follow-up. Transplant Proc 31: 2322–2323, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Grotz WH, Mundinger FA, Gugel B, Exner VM, Kirste G, Schollmeyer PJ: Bone mineral density after kidney transplantation. A cross-sectional study in 190 graft recipients up to 20 years after transplantation. Transplantation 59: 982–986, 1995 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Masse M, Girardin C, Ouimet D, Dandavino R, Boucher A, Madore F, Hébert MJ, Leblanc M, Pichette V: Initial bone loss in kidney transplant recipients: A prospective study. Transplant Proc 33: 1211, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Luan FL, Steffick DE, Ojo AO: Steroid-free maintenance immunosuppression in kidney transplantation: Is it time to consider it as a standard therapy? Kidney Int 76: 825–830, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Luan FL, Steffick DE, Gadegbeku C, Norman SP, Wolfe R, Ojo AO: Graft and patient survival in kidney transplant recipients selected for de novo steroid-free maintenance immunosuppression. Am J Transplant 9: 160–168, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.ter Meulen CG, van Riemsdijk I, Hené RJ, Christiaans MH, Borm GF, Corstens FH, van Gelder T, Hilbrands LB, Weimar W, Hoitsma AJ: No important influence of limited steroid exposure on bone mass during the first year after renal transplantation: A prospective, randomized, multicenter study. Transplantation 78: 101–106, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.ter Meulen CG, Hilbrands LB, van den Bergh JP, Hermus AR, Hoitsma AJ: The influence of corticosteroids on quantitative ultrasound parameters of the calcaneus in the 1st year after renal transplantation. Osteoporos Int 16: 255–262, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Aroldi A, Tarantino A, Montagnino G, Cesana B, Cocucci C, Ponticelli C: Effects of three immunosuppressive regimens on vertebral bone density in renal transplant recipients: A prospective study. Transplantation 63: 380–386, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nikkel LE, Mohan S, Zhang A, McMahon DJ, Boutroy S, Dube G, Tanriover B, Cohen D, Ratner L, Hollenbeak CS, Leonard MB, Shane E, Nickolas TL: Reduced fracture risk with early corticosteroid withdrawal after kidney transplant. Am J Transplant 12: 649–659, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rizzari MD, Suszynski TM, Gillingham KJ, Dunn TB, Ibrahim HN, Payne WD, Chinnakotla S, Finger EB, Sutherland DE, Kandaswamy R, Najarian JS, Pruett TL, Kukla A, Spong R, Matas AJ: Ten-year outcome after rapid discontinuation of prednisone in adult primary kidney transplantation. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 7: 494–503, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Woodle ES, First MR, Pirsch J, Shihab F, Gaber AO, Van Veldhuisen P, Astellas Corticosteroid Withdrawal Study Group : A prospective, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled multicenter trial comparing early (7 day) corticosteroid cessation versus long-term, low-dose corticosteroid therapy. Ann Surg 248: 564–577, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Edwards BJ, Desai A, Tsai J, Du H, Edwards GR, Bunta AD, Hahr A, Abecassis M, Sprague S: Elevated incidence of fractures in solid-organ transplant recipients on glucocorticoid-sparing immunosuppressive regimens. J Osteoporos 2011: 591793, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pistoia W, van Rietbergen B, Lochmüller EM, Lill CA, Eckstein F, Rüegsegger P: Estimation of distal radius failure load with micro-finite element analysis models based on three-dimensional peripheral quantitative computed tomography images. Bone 30: 842–848, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ashe MC, Khan KM, Kontulainen SA, Guy P, Liu D, Beck TJ, McKay HA: Accuracy of pQCT for evaluating the aged human radius: An ashing, histomorphometry and failure load investigation. Osteoporos Int 17: 1241–1251, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nickolas TL, Cremers S, Zhang A, Thomas V, Stein E, Cohen A, Chauncey R, Nikkel L, Yin MT, Liu XS, Boutroy S, Staron RB, Leonard MB, McMahon DJ, Dworakowski E, Shane E: Discriminants of prevalent fractures in chronic kidney disease. J Am Soc Nephrol 22: 1560–1572, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nickolas TL, Stein E, Cohen A, Thomas V, Staron RB, McMahon DJ, Leonard MB, Shane E: Bone mass and microarchitecture in CKD patients with fracture. J Am Soc Nephrol 21: 1371–1380, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nickolas TL, Stein EM, Dworakowski E, Nishiyama KK, Komandah-Kosseh M, Zhang CA, McMahon DJ, Liu XS, Boutroy S, Cremers S, Shane E: Rapid cortical bone loss in patients with chronic kidney disease. J Bone Miner Res 28: 1811–1820, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rajapakse CS, Leonard MB, Bhagat YA, Sun W, Magland JF, Wehrli FW: Micro-MR imaging-based computational biomechanics demonstrates reduction in cortical and trabecular bone strength after renal transplantation. Radiology 262: 912–920, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dempster DW: Bone histomorphometry in glucocorticoid-induced osteoporosis. J Bone Miner Res 4: 137–141, 1989 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dempster DW, Arlot MA, Meunier PJ: Mean wall thickness and formation periods of trabecular bone packets in corticosteroid-induced osteoporosis. Calcif Tissue Int 35: 410–417, 1983 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chavassieux P, Pastoureau P, Chapuy MC, Delmas PD, Meunier PJ: Glucocorticoid-induced inhibition of osteoblastic bone formation in ewes: A biochemical and histomorphometric study. Osteoporos Int 3: 97–102, 1993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lane NE, Sanchez S, Modin GW, Genant HK, Pierini E, Arnaud CD: Parathyroid hormone treatment can reverse corticosteroid-induced osteoporosis. Results of a randomized controlled clinical trial. J Clin Invest 102: 1627–1633, 1998 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hofbauer LC, Kühne CA, Viereck V: The OPG/RANKL/RANK system in metabolic bone diseases. J Musculoskelet Neuronal Interact 4: 268–275, 2004 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hofbauer LC, Rauner M: Minireview: Live and let die: Molecular effects of glucocorticoids on bone cells. Mol Endocrinol 23: 1525–1531, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Weinstein RS: Clinical practice. Glucocorticoid-induced bone disease. N Engl J Med 365: 62–70, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) Transplant Work Group : KDIGO clinical practice guideline for the care of kidney transplant recipients. Am J Transplant 9[Suppl 3]: S1–S155, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Casez JP, Lippuner K, Horber FF, Montandon A, Jaeger P: Changes in bone mineral density over 18 months following kidney transplantation: The respective roles of prednisone and parathyroid hormone. Nephrol Dial Transplant 17: 1318–1326, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Heaf J, Tvedegaard E, Kanstrup IL, Fogh-Andersen N: Hyperparathyroidism and long-term bone loss after renal transplantation. Clin Transplant 17: 268–274, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Akaberi S, Lindergård B, Simonsen O, Nyberg G: Impact of parathyroid hormone on bone density in long-term renal transplant patients with good graft function. Transplantation 82: 749–752, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Grotz WH, Mundinger FA, Rasenack J, Speidel L, Olschewski M, Exner VM, Schollmeyer PJ: Bone loss after kidney transplantation: A longitudinal study in 115 graft recipients. Nephrol Dial Transplant 10: 2096–2100, 1995 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Giannini S, Sella S, Silva Netto F, Cattelan C, Dalle Carbonare L, Lazzarin R, Marchini F, Rigotti P, Marcocci C, Cetani F, Pardi E, D’Angelo A, Realdi G, Bonfante L: Persistent secondary hyperparathyroidism and vertebral fractures in kidney transplantation: Role of calcium-sensing receptor polymorphisms and vitamin D deficiency. J Bone Miner Res 25: 841–848, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Laib A, Häuselmann HJ, Rüegsegger P: In vivo high resolution 3D-QCT of the human forearm. Technol Health Care 6: 329–337, 1998 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Laib A, Rüegsegger P: Calibration of trabecular bone structure measurements of in vivo three-dimensional peripheral quantitative computed tomography with 28-microm-resolution microcomputed tomography. Bone 24: 35–39, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hildebrand T, Laib A, Müller R, Dequeker J, Rüegsegger P: Direct three-dimensional morphometric analysis of human cancellous bone: Microstructural data from spine, femur, iliac crest, and calcaneus. J Bone Miner Res 14: 1167–1174, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Buie HR, Campbell GM, Klinck RJ, MacNeil JA, Boyd SK: Automatic segmentation of cortical and trabecular compartments based on a dual threshold technique for in vivo micro-CT bone analysis. Bone 41: 505–515, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Nishiyama KK, Macdonald HM, Buie HR, Hanley DA, Boyd SK: Postmenopausal women with osteopenia have higher cortical porosity and thinner cortices at the distal radius and tibia than women with normal aBMD: An in vivo HR-pQCT study. J Bone Miner Res 25: 882–890, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Burghardt AJ, Kazakia GJ, Ramachandran S, Link TM, Majumdar S: Age- and gender-related differences in the geometric properties and biomechanical significance of intracortical porosity in the distal radius and tibia. J Bone Miner Res 25: 983–993, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hildebrand T, Ruegseggar P: A new method for the model-independent assessment of thickness in three-dimensional images. J Microsc 185: 67–85, 1997 [Google Scholar]

- 45.MacNeil JA, Boyd SK: Improved reproducibility of high-resolution peripheral quantitative computed tomography for measurement of bone quality. Med Eng Phys 30: 792–799, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Pialat JB, Burghardt AJ, Sode M, Link TM, Majumdar S: Visual grading of motion induced image degradation in high resolution peripheral computed tomography: Impact of image quality on measures of bone density and micro-architecture. Bone 50: 111–118, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sode M, Burghardt AJ, Pialat JB, Link TM, Majumdar S: Quantitative characterization of subject motion in HR-pQCT images of the distal radius and tibia. Bone 48: 1291–1297, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Coresh J, Astor BC, McQuillan G, Kusek J, Greene T, Van Lente F, Levey AS: Calibration and random variation of the serum creatinine assay as critical elements of using equations to estimate glomerular filtration rate. Am J Kidney Dis 39: 920–929, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]