Abstract

Boron tris(trifluoroacetate) is identified as the first effective catalyst for the homoallyl- and homocrotylboration of aldehydes by cyclopropylcarbinylboronates. NMR spectroscopic studies and theoretical calculations of key intermediates and transition states both suggest that a ligand-exchange mechanism, akin to our previously reported PhBCl2-promoted homoallylations, is operative. Our experimental and theoretical results also suggest that the catalytic activity of boron tris(trifluoroacetate) might originate from more facile catalytic turnover of the trifluoroacetate ligands (in agreement with DFT calculations) or from a lower propensity for formation of off-pathway reservoir intermediates (as observed by 1H NMR). This work shows that carboxylates are viable catalytic ligands for homoallyl- and homocrotylations of carbonyl compounds and opens the door to the development of catalytic asymmetric versions of this transformation.

Introduction

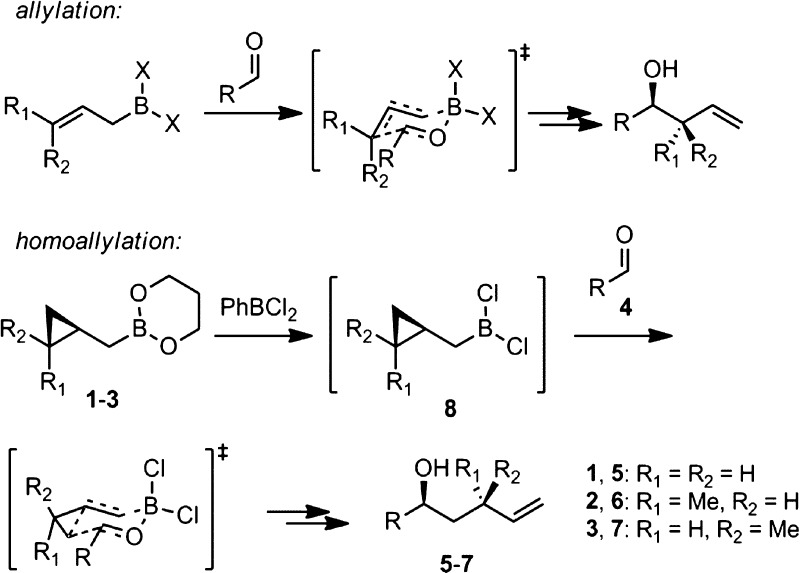

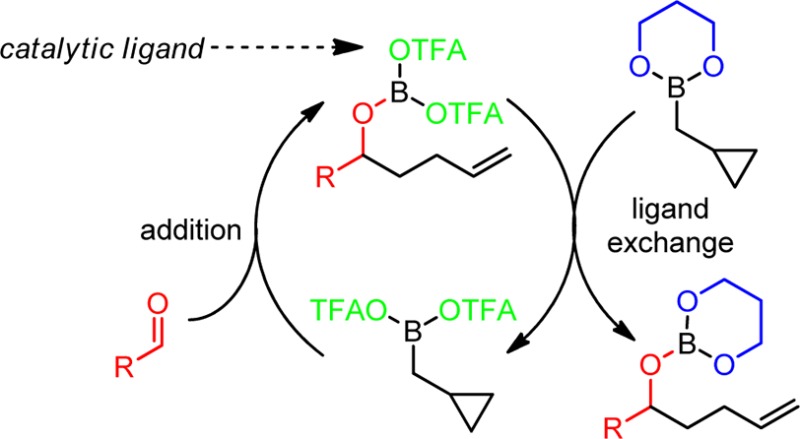

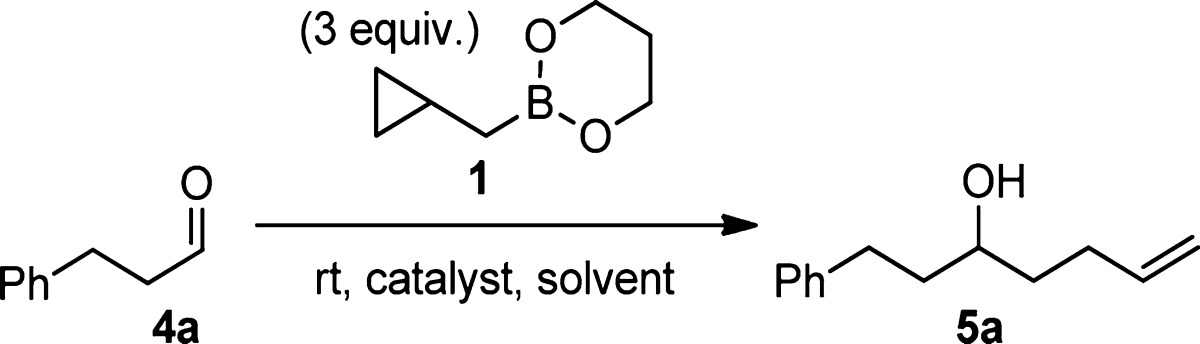

Allylboration of carbonyl compounds is an extensively studied transformation whose regio- and stereochemical outcomes are readily predicted from reagent structure via Zimmerman–Traxler transition-state models.1 We have recently shown that cyclopropanated allyl- and crotylboron reagents (1–3) are also capable of reacting through Zimmerman–Traxler transition states, affording homoallylation products (5–7) with complete regio-, diastereo-, and enantioselectivity (Scheme 1).2

Scheme 1. Homoallylation via the Allylation Paradigm.

We previously established PhBCl2 as an effective promoter for this reaction.2a Theoretical calculations and NMR studies support the involvement of (cyclopropylcarbinyl)dichloroboranes (8) as the homoallylating species, generated in situ by ligand exchange between 1–3 and PhBCl2. However, the PhBCl2 promoter must be used in excess and is strongly Lewis acidic. For greater substrate compatibility, it would be desirable to develop milder promoters which could be used catalytically. Moreover, in the case of achiral unsubstituted cyclopropylcarbinyl reagent 1, asymmetric homoallylation would only be possible with a chiral promoter, in which case it would also be preferable to use catalytic amounts.

Results and Discussion

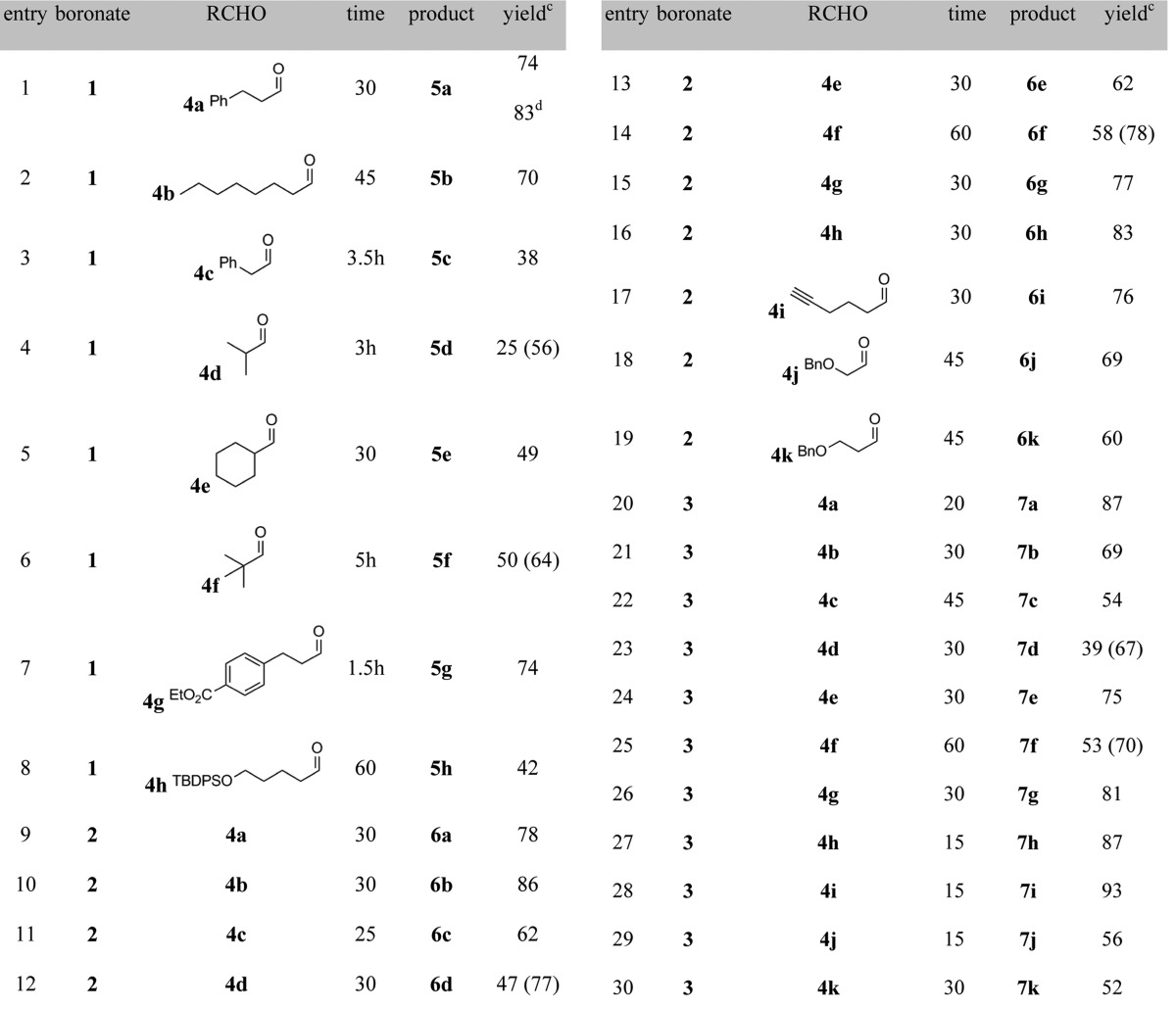

For these reasons, we tested several promoters under catalytic conditions (Table 1). When a catalytic amount (15 mol %) of PhBCl2 was used, no homoallylation product was observed at all. Other Lewis acids previously reported to catalyze allylation, such as Sc(OTf)3,3 AlCl3,4 and Cu(OTf)2,3b also failed to produce any homoallylation product, although aldehyde self-aldol products were observed in most cases after extended reaction times. On the other hand, we found that 15 mol % of boron tris(trifluoroacetate) (B(OTFA)3)5 effectively promoted the homoallylation in 74% yield. As we had previously seen with the stoichiometric PhBCl2-promoted homoallylation,2a coordinating solvents such as Et2O and THF hindered the reaction, and another noncoordinating solvent, toluene, effected a slower, lower yielding reaction.

Table 1. Selected Preliminary Experiments.

| entry | catalyst | amount (mol %) | solvent | time (h) | yielda (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | PhBCl2 | 15 | DCM | 3 | 0b |

| 2 | Sc(OTf)3 | 5 | CDCl3 | 2 | 0b |

| 3 | Sc(OTf)3 | 10 | CDCl3 | 20 | 0b |

| 4 | AlCl3 | 10 | CDCl3 | 24 | 0b |

| 5 | Cu(OTf)2 | 10 | CDCl3 | 168 | 0b |

| 6 | B(OTFA)3 | 15 | DCM | 0.5 | 74c |

| 7 | B(OTFA)3 | 15 | Et2O | 18 | 3 |

| 8 | B(OTFA)3 | 15 | THF | 18 | 1 |

| 9 | B(OTFA)3 | 15 | pentane | 4 | 1 |

| 10 | B(OTFA)3 | 15 | toluene | 1.5 | 26 |

NMR yield, except entry 6.

Forcing the reaction with higher temperatures resulted in self-aldol products from 4a and/or ring opening of reagent 1.

Isolated yield.

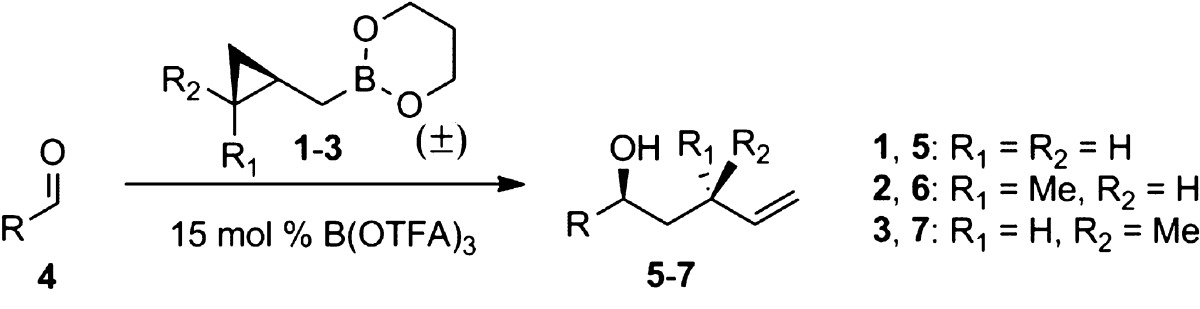

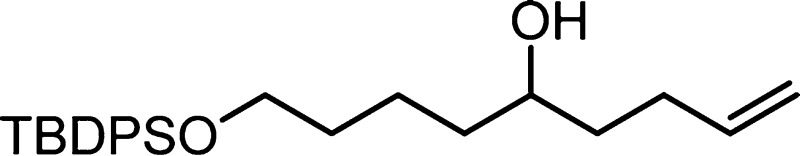

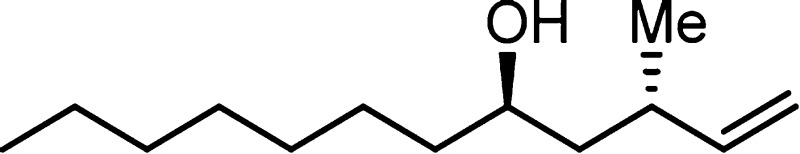

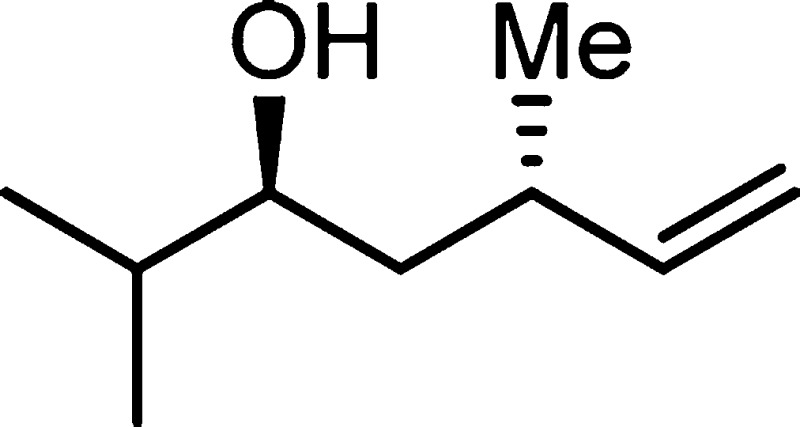

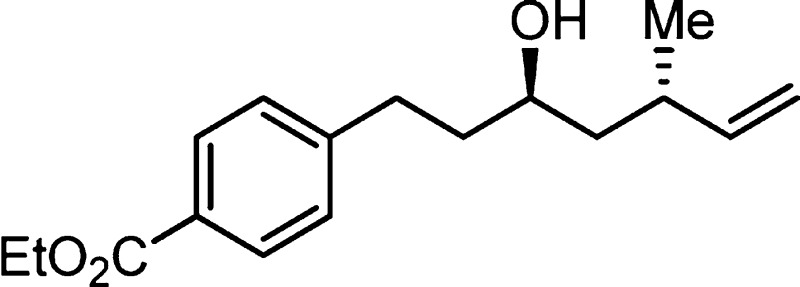

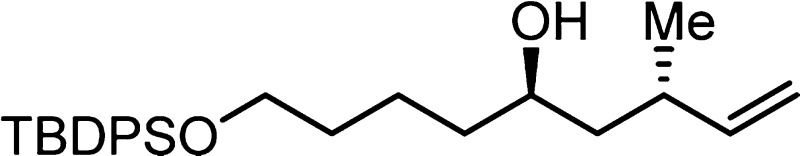

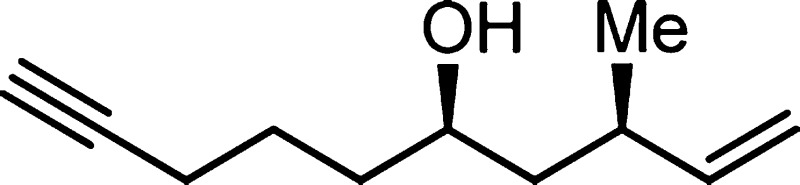

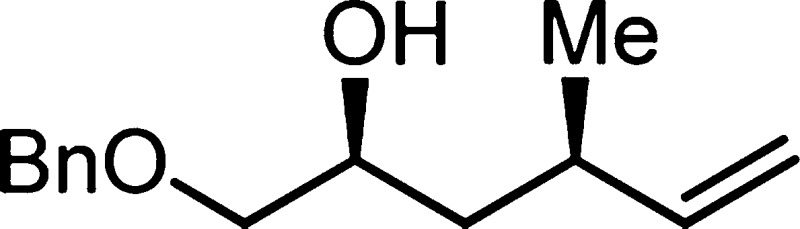

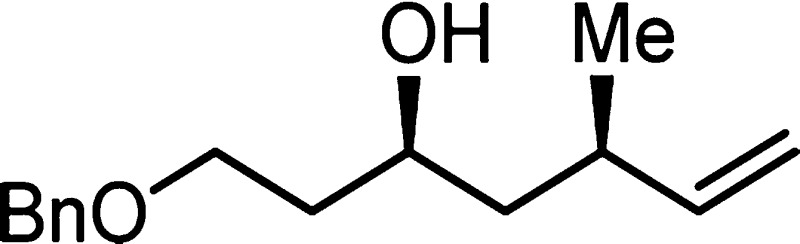

We thus investigated the scope of the B(OTFA)3 catalyst with a panel of aldehydes and cyclopropylcarbinylboronates 1–3 (Table 2). In parallel with what we had observed for stoichiometric PhBCl2-promoted reactions, under B(OTFA)3 catalysis, the cis (2) and trans boronates (3) reacted faster and gave higher yields than the unsubstituted reagent 1. Interestingly, 15 mol % of B(OTFA)3 also promoted a faster reaction than did stoichiometric PhBCl2. As seen in entry 1, the reaction of dihydrocinnamaldehyde (4a) was complete after 30 min at room temperature, as compared with 14 h with our previous PhBCl2-promoted conditions.2a Similarly, pivaldehyde (4f) reacted completely with 2 in about 60 min under B(OTFA)3 catalysis (entry 14), as compared with 7 days under PhBCl2 conditions.2b The ester (4g), the silyl ether (4h), and the terminal alkyne (4i) were all well tolerated. The compatibility of the B(OTFA)3 catalyst with the benzyl ether (4j and 4k) is also noteworthy, as attempted PhBCl2-mediated reactions with these substrates result in immediate debenzylation.6

Table 2. Catalytic Homoallylation Scopea.

Reagents 2 and 3 were used in racemic form.

All reactions were performed with 3.0 equiv f boronates 1–3, except where indicated. Entries 3–8 are reactions run at 45 °C, and all others were run at rt.

Isolated yields for reactions on 0.1–0.3 mmol scale, except where indicated. For volatile substrates, NMR yields are listed in parentheses. The diastereomeric ratios, as determined by 1H NMR integration, were >20:1 for 6a–k and >12:1 for 7a–k.

Isolated yield for reaction run on 1 mmol scale and with 2.0 equiv of 1.

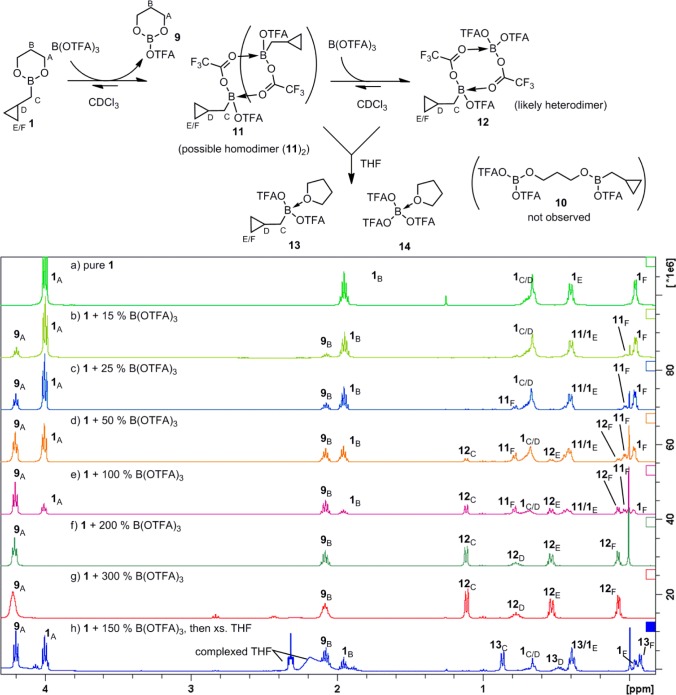

In order to investigate the possible structure of the active homoallylating species, we conducted 1H and 11B NMR spectroscopic studies. To begin, B(OTFA)3 showed a 11B NMR resonance at δ 3.4, consistent with tetracoordinate boron, suggesting a bridged dimer structure, [B(OTFA)3]2 (although, for simplicity, we will continue to refer to this compound as a monomer).7 The dimeric nature of boron trifluoroacetates was further evident from the 1H NMR spectrum (Figure 1) upon mixing boronate 1 (spectrum a)2a with various amounts of B(OTFA)3 (spectra b–g). As B(OTFA)3 was titrated in, an intermediate set of cyclopropylcarbinyl resonances (11C–F), and later a final set (12C–F), became visible, simultaneous with the conversion of propanediol derived peaks from 1A,B to just one new set of peaks, 9A,B. Conversion of 1 entirely to 12 and 9 was complete only upon addition of two full equivalents of B(OTFA)3 (spectrum f) and could be driven backward again by adding more 1. Furthermore, no peak corresponding to unreacted B(OTFA)3 could be seen in the 19F NMR spectra when 1 was combined with 1–2 equiv of B(OTFA)3. Together, these observations strongly support a picture in which cyclopropylcarbinylB(OTFA)2 (11) initially generated from 1 + B(OTFA)3 is ultimately captured as a heterodimeric complex RB(OTFA)2·B(OTFA)3 (12). Because only two sets of propanediol CH2–O peaks were ever observed at around δ 4, we rule out the possibility that the peaks 11C–F could correspond to a partial ligand transfer product 10, and we speculate that 11 is either the monomeric or dimeric RB(OTFA)2 species. Consistent with this overall picture, the mixture of 11/12 is converted to a single cyclopropylcarbinyl species (13C–F, spectrum h) upon addition of THF, which we have assigned as the THF complex 13.

Figure 1.

400 MHz 1H NMR spectra of 1 in the presence of 0–300 mol % of B(OTFA)3.

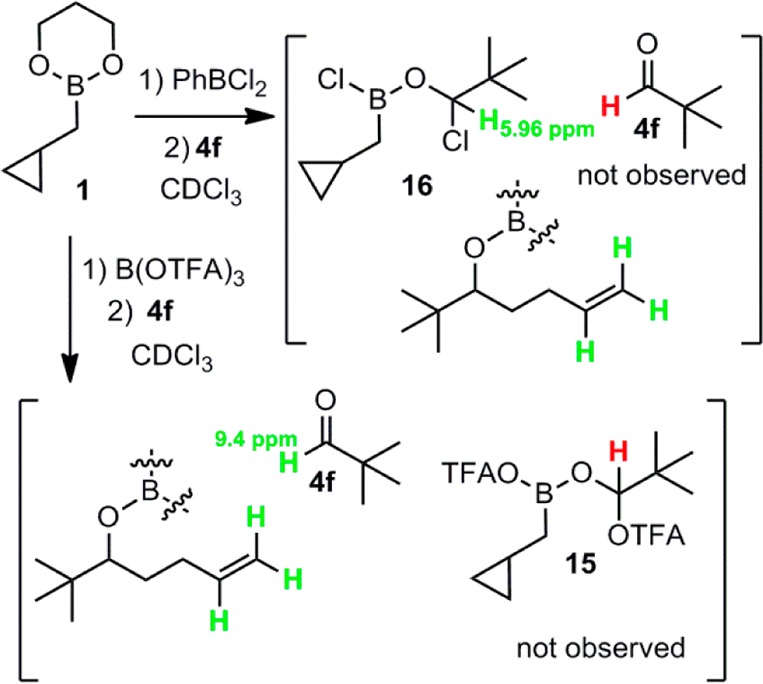

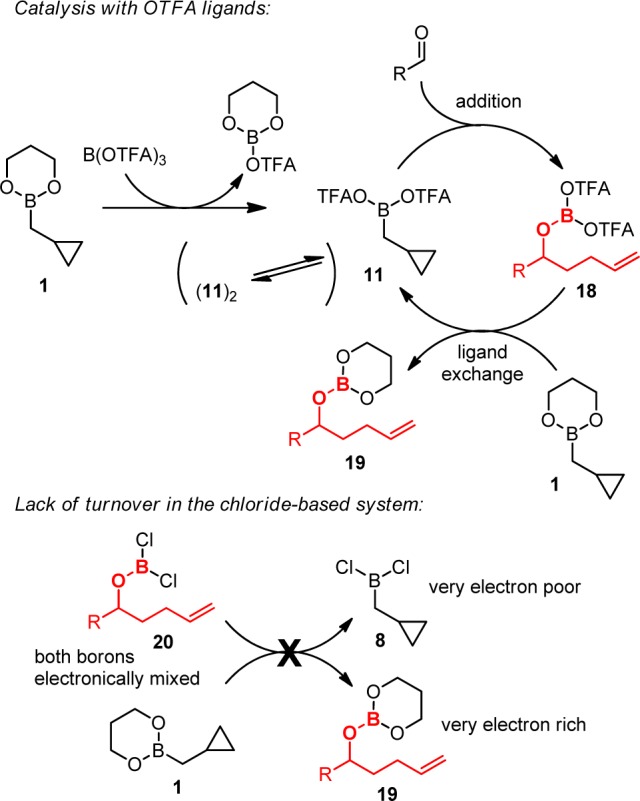

Upon addition of the aldehyde to 11/12, we also looked for possible formation of OTFA adducts to the aldehyde carbon (15), analogous to chloride adduct 16, which we had observed as reservoir species when PhBCl2 was used as promotor (Scheme 2).2b When aldehyde is added to the PhBCl2-promoted reaction, it is immediately converted entirely to 16, which then slowly converts to product. After 1 was mixed with 15% B(OTFA)3, we added aldehyde 4f and observed only product peaks and unconsumed aldehyde in the 1H NMR. No peaks corresponding to putative OTFA adduct 15 were observed in the ∼4.6–7 ppm δ region, suggesting that 15 is most likely absent.

Scheme 2. –OTFA/RCHO Adducts Not Observed by 1H NMR.

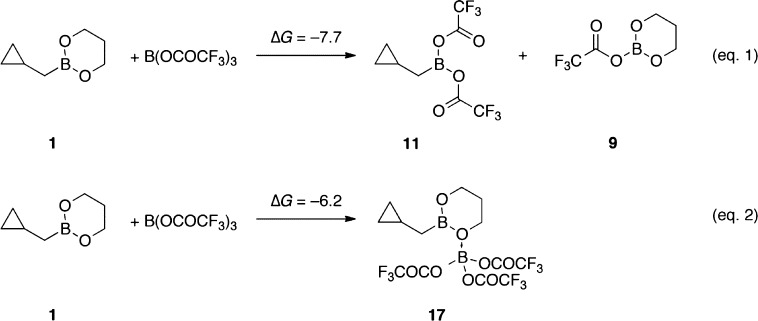

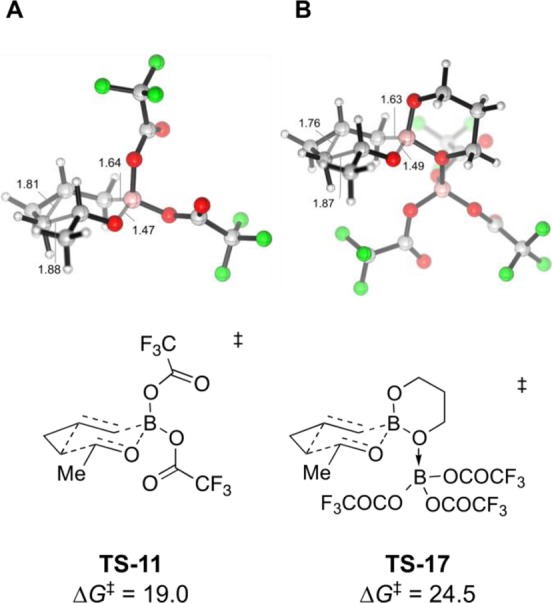

We performed density functional theory (DFT) calculations to investigate the possible intermediates implicated in these homoallylations. As shown in Scheme 3, the ligand-exchange reaction between 1 and B(OTFA)3 to form 11 and 9 is exergonic, with ΔGrxn = −7.7 kcal/mol (eq 1). The Lewis acid–base reaction between 1 and B(OTFA)3 forming adduct 17 is less exergonic and has a ΔGrxn value of only −6.2 kcal/mol (eq 2). The Zimmerman–Traxler transition structures for the homoallylation of acetaldehyde involving 11 and 17 were also computed (Figure 2). The free energy of activation (ΔG⧧) is 19.0 kcal/mol involving 11 (TS-11), but 24.5 kcal/mol starting from 17 (TS-17). Thus, the DFT calculations suggest that the homoallylating species is the spectroscopically observable species 11 generated in situ from 1 and B(OTFA)3.

Scheme 3. Energetics of Formation of Intermediates 11 and 17 (B3LYP-D3/TZVP, in kcal/mol).

Figure 2.

Zimmerman–Traxler transition structures (B3LYP-D3/TZVP, ΔG⧧ values in kcal/mol) for homoallylborations of acetaldehyde by 11 (A) and 17 (B).

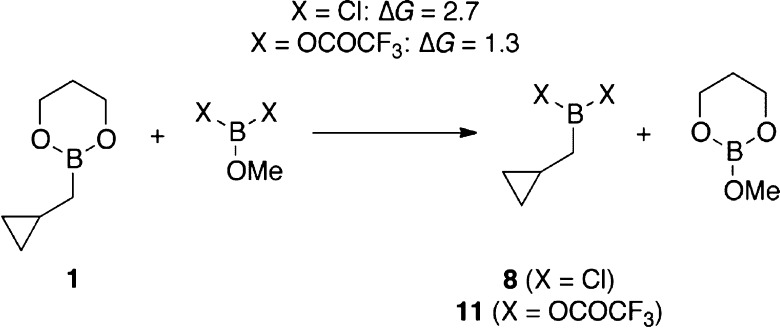

The proposed mechanism of catalysis is depicted in Scheme 4. Exchange of diol and OTFA ligands between 1 and B(OTFA)3 produces 11 (possibly dimeric), which reacts with aldehyde to afford product 18.8 Trifluoroacetates then exchange with the propanediol ligand on the next catalytic equivalent of 1 to regenerate 11. In the analogous PhBCl2-promoted reaction, chlorides may fail to turn over for multiple reasons. We computed the reaction energies for the ligand exchange step involved in catalytic turnover, using a methyl group to represent the alkyl chain in the homoallylated products 18–20 (Scheme 5). With ΔG = 2.7 kcal/mol, the ligand exchange in the chloride system (X = Cl) is calculated to be thermodynamically less favorable than the system employing the trifluoroacetate ligand (X = OCOCF3), for which we calculated a ΔG value of 1.3 kcal/mol. The uphill nature of this turnover step is intuitive because of the electronic properties of the ligands. In the formation of 11 and 19 from 1 and 18, all resonance electron-donating ligands (3 alkoxides) must be collected together on the boron atom of 19, and all electron-withdrawing ligands (OCOCF3 and alkyl) must be collected on the boron of 11. By contrast, prior to turnover, species 1 and 18 both contain mixtures of electron-donating and -withdrawing ligands, intuitively a lower energy arrangement. By this reasoning, the analogous turnover step ought to be even more uphill in the case of the more electronegative X = Cl, and this notion is consistent with the computational result. Apart from the increased difficulty of the turnover step, an alternative explanation for the difference in catalytic activity for X = Cl vs OCOCF3 is the fact that the chlorides from PhBCl2 are largely sequestered as aldehyde adduct 16 (Scheme 2), whereas the less nucleophilic trifluoroacetates seem not to form analogous adduct 15 and thus remain mobile between boron atoms.

Scheme 4. Proposed Catalytic Cycle.

Scheme 5. Energetics of Ligand Exchange Implicated in Catalytic Turnover (B3LYP-D3/TZVP, in kcal/mol).

Conclusion

In conclusion, we have identified boron tris(trifluoroacetate) as an effective catalyst for the homoallylation of aldehydes. Spectroscopic studies and DFT calculations suggest that the active homoallylating species is the ligand-exchange product 11 rather than the Lewis adduct 17. The problem of aldehyde sequestration by nucleophilic addition of a ligand on the boron Lewis acid, which was previously observed under PhBCl2-promoted conditions,2b is circumvented as the trifluoroacetate ligand in the active catalyst is less nucleophilic than chloride. Studies with structurally related chiral boron catalysts are under way and will be reported in due course.

Experimental Section

General Information and Methods

All solvents for routine isolation of products and chromatography were reagent grade. Aldehydes were purchased from commercial sources and freshly distilled, except for aldehydes 4g,94h,104i,11 and 4k,12 which were synthesized based on literature procedures. Flash chromatography was performed using Silicycle R10030B F60 SiliaFlash silica gel (230–400 mesh) with the indicated solvents. All reactions were monitored by thin-layer chromatography on 0.25 mm silica plates (F-254), except for the reactions with isobutryaldehyde (4d) and pivaldehyde (4f), which were monitored by GC/MS (see below). TLC plates were stained with vanillin or KMnO4. Reactions with volatile products were monitored by GC/MS with a triple-axis detector. NMR spectra were recorded with 400 MHz spectrometers (proton frequency) for 1H, 11B, 13C, and 19F NMR. The 1H NMR data are reported as the chemical shift in parts per million, multiplicity (s, singlet; d, doublet; dd, doublet of doublets; t, triplet; q, quartet; m, multiplet), and number of protons. 11B spectra are reported as ppm relative to BF3·OEt2. 13C spectra are referenced to the central peak of CDCl3 as 77.0 ppm. 19F spectra are reported as ppm relative to CFCl3. HRMS was performed using electrospray (ES) or electron-impact (EI) ionization, as needed.

Synthesis of Boronates

Starting boronates 1, 2, and 3 were prepared according to our previous literature procedure, and characterization data were reported previously, with the trans reagent (2) containing ∼5% cis isomer by 1H NMR.2 The catalyst B(OTFA)3 was prepared according to a literature procedure.5 Thus, a solution of trifluoroacetic acid in pentane (3.0 equiv, or 3.0 mL in 100 mL pentane) was transferred by cannulation to a solution of BBr3 in pentane (1.0 equiv, or 1.3 mL in 100 mL pentane), followed by 50 mL of pentane rinse. After 1 h of stirring, the solvent was distilled off in vacuo (using manifold vacuum, not a rotary evaporator), and the resulting material was subjected to ∼1 mmHg vacuum overnight to yield a white powder in 64% yield (3 g). NMR spectroscopic data for this compound have not previously been reported: 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ 163.2 (q, JCF = 46 Hz), 113.7 (q, JCF = 284 Hz); 11B NMR (128 MHz, CDCl3) δ 3.4. 19F NMR (376 MHz, CDCl3) δ 75.7.

General Experimental Procedure for the Synthesis of Bishomoallyl alcohols

To a solution of B(OTFA)3 (7.5 mol %) in anhydrous DCM (enough to produce a 0.2 M solution of aldehyde) in an oven-dried Schlenk tube was added boronate (3.0 equiv). The solution was stirred under nitrogen for 1 min. Aldehyde (1.0 equiv) was added, and the reaction mixture was stirred at 45 °C (for products 5c–h) or room temperature (all other products). After TLC analysis showed consumption of aldehyde, the reaction was quenched with 3 M sodium hydroxide, and the mixture was extracted with EtOAc three times. The organic layers were then dried over MgSO4, combined, and concentrated on a rotary evaporator, and the crude reaction mixture was purified by flash chromatography (EtOAc/hexane) to yield the desired product. For reactions with benzyl-protected products (employing 4j and 4k), flash chromatography was performed with 5% EtOAc/toluene. For volatile substrates (4d,f), reactions were monitored by GC/MS, extraction was done with DCM, and solvent was removed with no lower than 200 Torr vacuum, until a small amount of solvent remained, at which point the remaining solvent was blown off under a gentle stream of nitrogen. For these substrates, chromatography was performed with Et2O/pentane solvent mixtures.

Characterization Data of New Compounds

5h: colorless oil (0.130 mmol scale, 21.2 mg,

41%); 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.71–7.61

(m, 4H), 7.45–7.32 (m, 6H), 5.90–5.77 (m, 1H), 5.04

(app d, J = 17.3 Hz, 1H), 4.97 (app d, J = 10.2 Hz, 1H), 3.67 (t, J = 6.3 Hz, 2H), 3.64–3.53

(m, 1H), 2.26–2.05 (m, 2H), 1.70–1.30 (m, 9H + H2O), 1.05 (s, 9H); 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ 138.6, 135.6, 134.1, 129.5, 127.6, 114.7, 71.4, 63.8, 37.1,

36.4, 32.5, 30.0, 26.9, 21.9, 19.2; IR (neat) 3356 (br), 3070, 2931,

2858, 1724, 1466, 1427, 1109, 702; HRMS (ES-TOF) (m/z) calcd for C25H37O2Si (M + H)+ 397.2568, found 397.2563.

5h: colorless oil (0.130 mmol scale, 21.2 mg,

41%); 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.71–7.61

(m, 4H), 7.45–7.32 (m, 6H), 5.90–5.77 (m, 1H), 5.04

(app d, J = 17.3 Hz, 1H), 4.97 (app d, J = 10.2 Hz, 1H), 3.67 (t, J = 6.3 Hz, 2H), 3.64–3.53

(m, 1H), 2.26–2.05 (m, 2H), 1.70–1.30 (m, 9H + H2O), 1.05 (s, 9H); 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ 138.6, 135.6, 134.1, 129.5, 127.6, 114.7, 71.4, 63.8, 37.1,

36.4, 32.5, 30.0, 26.9, 21.9, 19.2; IR (neat) 3356 (br), 3070, 2931,

2858, 1724, 1466, 1427, 1109, 702; HRMS (ES-TOF) (m/z) calcd for C25H37O2Si (M + H)+ 397.2568, found 397.2563.

6b: colorless oil (0.324 mmol scale,

55.5 mg, 86%); 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ

5.78 (ddd, 1H, J = 17.3, 10.2, 7.8), 5.03 (br d,

1H, J = 17.2), 4.93 (br d, 1H, J = 10.2), 3.72–3.63 (m, 1H), 2.33 (app sept, 1H, J = 7.1), 1.53–1.19 (m, 15H), 1.02 (d, 3H, J = 6.7), 0.88 (t, 3H, J = 6.8); 13C NMR

(100 MHz, CDCl3) δ 145.2, 112.7, 70.4, 44.4, 37.7,

35.5, 31.8, 29.6, 29.3, 25.5, 22.6, 20.2, 14.1; IR (neat) 3341 (br),

3070, 2958, 2923, 2856, 1641, 1557, 1459, 994, 909, 725; HRMS (EI-TOF)

calcd for C13H26O (M+) 198.1984,

found 198.1982.

6d: colorless oil

(0.250 mmol scale, 16.8 mg, 47%); 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 5.81 (ddd, 1H, J = 17.2, 10.2,

7.7), 5.04 (ddd, 1H, J =

17.2, 1.4, 1.4), 4.94 (br d, 1H, J = 10.3), 3.52–3.44

(m, 1H), 2.34 (app sept, 1H, J = 7.0), 1.71–1.58

(m, 1H), 1.50 (br d, 1H, J = 4.4), 1.48–1.33

(m, 2H), 1.02 (d, 3H, J = 6.6), 0.92 (d, 3H, J = 6.8), 0.90 (d, 3H, J = 6.8); 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ 145.4, 112.6, 75.0, 41.1,

35.5, 33.7, 19.9, 18.7, 16.9; IR (neat) 3359 (br), 3072, 2961, 2883,

1638, 1461, 1374, 988, 910; HRMS (EI-TOF) calcd for C6H11O (M – iPr–)+ 99.0810,

found 99.0812, calcd for C4H9O (M – homocrotyl–) 73.0753, found 73.0654.

6g: colorless oil (0.124 mmol scale, 38.6 mg,

77%); 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.96 (app

d, 2H, J = 8.2), 7.26 (app d, 2H, J = 8.1), 5.76

(ddd, 1H, J = 17.2, 10.2, 8.0), 5.01 (br d, 1H, J = 17.2), 4.93 (br dd, 1H, J = 10.3, 1.3),

4.36 (q, 2H, J = 7.1), 3.77–3.62 (m, 1H),

2.93–2.79 (m, 1H), 2.79–2.64 (m, 1H), 2.32 (app sept,

1H, J = 7.1), 1.96–1.65 (m, 3H), 1.54 (app

dt, 1H, J = 13.9, 8.1), 1.44 (app td, 1H, J = 6.8, 4.2), 1.38 (t, 3H, J = 7.1), 1.00

(d, 3H, J = 6.8); 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ 166.6, 147.7, 144.9, 129.6, 128.4, 128.1, 113.0,

69.8, 60.8, 44.5, 38.9, 35.7, 31.9, 20.4, 14.3; IR (neat) 3402 (br),

3071, 2970, 2929, 2869, 1712, 1610, 1452, 1274, 1176, 1104, 1021,

912, 856, 763; HRMS (ES-TOF) calcd for C17H25O3 (M + H)+ 277.1804, found 277.1802.

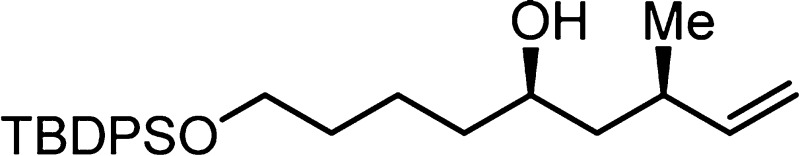

6h: colorless oil (0.202 mmol scale, 67.1 mg,

81%); 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.70–7.62

(m, 4H), 7.44–7.32 (m, 6H), 5.77 (ddd, J =

17.4, 10.2, 7.8 Hz, 1H), 5.01 (app d, J = 17.4 Hz,

1H), 4.93 (app d, J = 10.2 Hz, 1H), 3.67 (t, 6.4

Hz, 2H), 3.69–3.60 (m, 1H), 2.32 (app sept, J = 7 Hz, 1H), 1.69–1.30 (m, 9 H + H2O), 1.05 (s,

9H), 1.01 (d, 6.7 Hz, 3H); 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ 145.2, 135.6, 134.1, 129.5, 127.6, 112.7, 70.3, 63.8, 44.4,

37.4, 35.4, 32.5, 26.9, 21.7, 20.2, 19.2; IR (neat) 3374 (br), 3071,

2930, 2858, 1960, 1890, 1822, 1725, 1460, 1427, 1108, 701; HRMS (ES-TOF)

(m/z) calcd for C26H38O2NaSi (M + Na)+ 433.2539, found 433.2537.

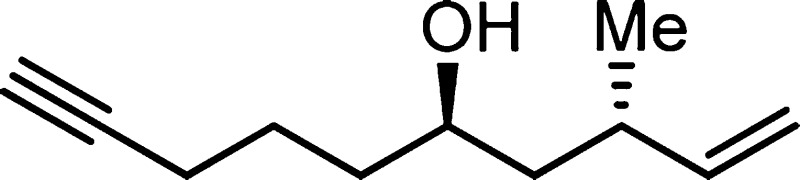

6i: colorless oil (0.191 mmol scale, 24.1 mg,

76%); 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 5.78 (ddd,

1H, J = 17.2, 10.3, 8.0), 5.04 (ddd, 1H, J =

17.2, 1.6, 1.0), 4.95 (ddd, 1H, J = 10.2, 1.6, 0.6),

3.76–3.66 (m, 1H), 2.33 (app sept, 1H, J =

7.1), 2.23 (td, 2H, J = 6.6, 2.7), 1.95 (t, 1H, J = 2.7), 1.76–1.36 (m, 7H + water), 1.02 (d, 3H, J = 6.6); 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3)

δ 145.0, 113.0, 84.4, 70.0, 68.4, 44.5, 36.5, 35.6, 24.5, 20.3,

18.4; IR (neat) 3388 (br), 3299, 3075, 2924, 2118 (weak), 1839, 1818,

1638, 1454, 1092, 994, 912; HRMS (EI-TOF) calcd for C11H18O (M+) 166.1358, found 166.1358.

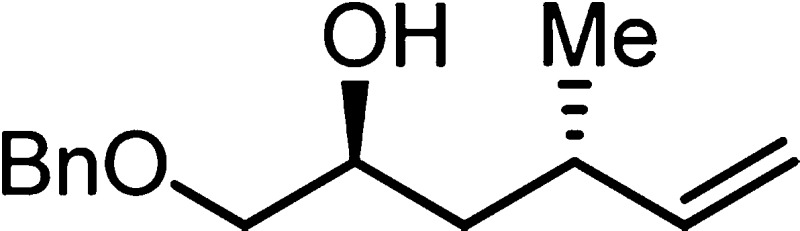

6j: colorless oil (0.151 mmol scale, 23.2 mg,

69%); 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.29–7.39

(m, 5H), 5.73–5.81 (m, 1H), 4.99 (d, J = 17

Hz, 1H), 4.93 (d, J = 10 Hz, 1H), 4.57 (s, 2H), 3.86–3.94

(m, 1H), 3.52 (dd, J = 3, 9 Hz, 1H), 3.34 (dd, J = 8, 10 Hz, 1H), 2.31–2.36 (m, 2H), 1.56–1.60

(m, 1H + H2O), 1.31–1.38 (m, 1H) 1.03 (d, J = 7 Hz, 3H); 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ 144.6, 138.0, 128.4, 127.8, 127.7, 112.7, 74.5, 73.3, 68.6,

39.7, 34.3, 19.8; IR (neat) 3468, 3064, 3028, 2963, 2924, 2866, 1638,

1453, 1099, 912, 749 cm–1; HRMS (ES-TOF) (m/z) [M + Na]+ calcd for C14H20O2Na 243.1361, found 243.1362.

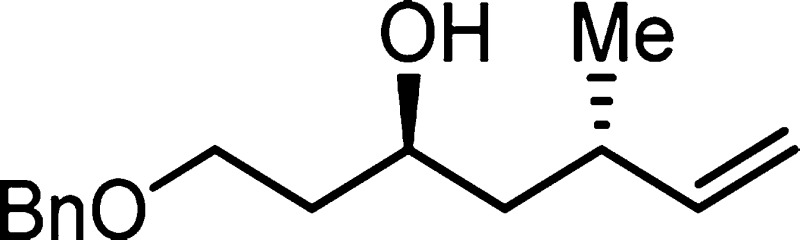

6k: colorless oil (0.173 mmol scale, 24.3 mg,

60%); 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.27–7.38

(m, 5H), 5.72–5.81 (m, 1H), 5.00 (d, J = 17

Hz, 1H), 4.93 (d, J = 10 Hz, 1H), 4.53 (s, 2H), 3.85–3.93

(m, 1H), 3.70–3.75 (m, 1H), 3.63–3.68 (m, 1H), 2.85

(s, 1H), 2.29–2.39 (m, 1H), 1.72–1.79 (m, 2H), 1.55–1.62

(m, 2H), 1.31–1.38 (m, 1H), 1.03 (d, J = 7

Hz, 3H); 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ 145.0,

137.9, 128.4, 127.7, 127.6, 112.5, 73.3, 69.4, 69.1, 44.2, 36.6, 34.7,

19.9; IR (neat) 3425, 3065, 3031, 2960, 2930, 2866, 1638, 1458, 1098,

911, 748 cm–1; HRMS (ES-TOF) (m/z) [M + Na]+ calcd for C15H22O2Na 257.1517, found 257.1519.

7h: colorless oil (0.173 mmol scale, 59.8 mg,

84%); 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.70–7.63

(m, 4H), 7.44–7.32 (m, 6H), 5.67 (ddd, J =

17.3, 10.2, 8.3 Hz, 1H), 5.02 (app d, 17.3 Hz, 1H), 4.95 (app d, 10.2

Hz, 1H), 3.67 (t, J = 6.3 Hz, 2H), 3.63–3.55

(m, 1H), 2.46–2.35 (m, 1H), 1.65–1.30 (m, 9H + H2O); 1.05 (s, 9H), 1.01 (d, 6.7 Hz, 3H); 13C NMR

(100 MHz, CDCl3) δ 144.2, 135.5, 134.1, 129.5, 127.6,

113.4, 69.6, 63.8, 44.2, 37.6, 34.7, 32.5, 26.9, 21.8, 21.2, 19.2;

IR (neat) 3356 (br), 3070, 2930, 2858, 1960, 1890, 1820, 1724, 1460,

1427, 1108, 700; HRMS (ES-TOF) (m/z) calcd for C26H38O2NaSi (M + Na)+ 433.2539, found 433.2538.

7i: colorless oil (0.242 mmol scale, 37.5 mg,

93%); 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 5.57 (ddd, J = 8.2, 10.3, 17.7 Hz, 1H) 5.03 (d, 17.7 Hz, 1H), 4.97

(d, 10.3 Hz, 1H), 3.71–3.61 (m, 1H), 2.46–2.34 (m, 1H),

2.26–2.17 (m, 2H) 1.95 (t, 2.6 Hz, 1H), 1.78–1.63 (m,

1H), 1.63–1.33 (m, 6H + H2O), 1.02 (d, J = 6.8 Hz, 3H); 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ

144.0, 113.5, 83.3, 69.2, 68.4, 44.3, 36.8, 34.7, 24.6, 21.1, 18.4

IR (neat) 3400 (br), 3301, 3078, 2950, 2115 (weak), 1639, 1454, 995,

912; HRMS (EI-TOF) calcd for C11H18O (M+) 166.1358, found 166.1359.

7j: colorless oil (0.191 mmol, 23.6 mg, 56%); 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.28–7.38

(m, 5H), 5.60–5.69 (m, 1H), 5.03 (d, J = 17

Hz, 1H), 4.96 (d, J = 10 Hz, 1H), 4.55 (s, 2H), 3.84–3.90

(m, 1H), 3.48 (dd, J = 3, 9 Hz, 1H), 3.32 (dd, J = 8, 10 Hz, 1H), 2.37–2.49 (m, 1H), 2.25–2.33

(m, 1H), 1.44–1.52 (m, 1H), 1.26–1.33 (m, 1H), 1.03

(d, J = 7 Hz, 3H); 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ 143.7, 138.0, 128.4, 127.7, 127.6, 113.6, 74.9,

73.3, 68.4, 39.9, 34.4, 21.2; IR (neat) 3463, 3065, 2961, 2928, 2865,1640,

1495, 1275, 1260, 1104, 913, 750 cm–1; HRMS (ES-TOF)

(m/z) [M + Na]+ calcd

for C14H20O2Na 243.1361, found 243.1359.

7k: colorless oil (0.101 mmol, 12.5 mg, 52%); 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.27–7.37 (m, 5H), 5.64–5.73 (m, 1H), 5.04 (d, J = 17 Hz, 1H), 4.97 (d, J = 10 Hz, 1H), 4.52 (s, 2H), 3.82–3.90 (m, 1H), 3.62–3.74 (m, 2H), 2.76 (s, 1H), 2.38–2.47 (m, 1H), 1.72–1.78 (m, 2H), 1.48–1.55 (m, 2H), 1.31–1.37 (m, 1H), 1.02 (d, J = 7 Hz, 3H); 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ 144.1, 138.0, 128.4, 127.7, 127.6, 113.3, 73.3, 69.1, 69.0, 44.4, 37.0, 34.5, 21.1; IR (neat) 3411, 3065, 3031, 2959, 2923, 2865, 1639, 1453, 1275, 1097, 913, 749 cm–1; HRMS (ES-TOF) (m/z) [M + Na]+ calcd for C15H22O2Na 257.1517, found 257.1513.

Scale, weights, yields, and references listing spectral data for reactions producing known compounds:

5a(13) (1.00 mmol scale, 158 mg, 83%); 5b(14) (0.215 mmol scale, 28 mg, 70%); 5c(15) (0.200 mmol scale, 13 mg, 38%); 5d(16) (0.120 mmol scale, 3.8 mg, 25% (56% NMR)); 5e(17) (0.139 mmol scale, 12 mg, 49%); 5f(18) (0.116 mmol scale, 8.3 mg, 50% (64% NMR)); 5g(2a) (0.156 mmol scale, 30 mg, 74%); 6a(19) (0.255 mmol scale, 41 mg, 78%); 6c(20) (0.192 mmol scale, 23 mg, 62%); 6e(21) (0.238 mmol scale, 27 mg, 62%); 6f(21) (0.217 mmol scale, 20 mg, 58% (78% NMR)); 7a(19) (0.246 mmol scale, 44 mg, 87%); 7b(2b) (0.179 mmol scale, 25 mg, 69%); 7c(2b) (0.122 mmol scale, 13 mg, 54%); 7d(2b) (0.135 mmol scale, 7.5 mg, 39% (67% NMR)); 7e(2b) (0.168 mmol scale, 23 mg, 75%); 7f(2b) (0.141 mmol scale, 12 mg, 53% (70% NMR)); 7g(2b) (0.204 mmol scale, 46 mg, 81%).

Computational Methods

The geometry optimizations and frequency computations were performed in the gas phase using the dispersion-corrected density functional B3LYP22−25-D326 (with Becke–Johnson damping27−30) in conjunction with the triple-ζ TZVP31 basis set. The errors in the computed entropies introduced by the treatment of low-frequency modes as harmonic oscillators were corrected for by a quasiharmonic approximation described by Cramer and Truhlar,32 in which the vibrational frequencies lower than 100 cm–1 were raised to 100 cm–1 when computing the vibrational partition functions using the usual harmonic oscillator approximation.

All of the quantum chemical computations were performed using Gaussian 09.33 All structural representations were generated with CYLview.34

Acknowledgments

I.J.K. gratefully acknowledges the generous support of Brandeis University, the Donors of the American Chemical Society Petroleum Research Fund (51975-DNI), and the National Science Foundation CAREER program (CHE-1253363). We are grateful to Prof. Casey Wade insightful discussions. K.N.H. acknowledges financial support by the National Institute of General Medical Sciences, National Institutes of Health (GM36700). The computational resources from UCLA Institute for Digital Research and Education and the National Science Foundation through XSEDE resources provided by the XSEDE Science Gateways program are also acknowledged.

Supporting Information Available

1H NMR and 13C NMR spectra. Full citation of ref (33). Computational details and energies and Cartesian coordinates of all computed structures. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Funding Statement

National Institutes of Health, United States

Supplementary Material

References

- For a recent review, see:Lachance H.; Hall D. G.. Organic Reactions; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: New York, 2009; pp 1–574. [Google Scholar]

- a Pei W.; Krauss I. J. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011, 133, 18514–18517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Lin H.; Pei W.; Wang H.; Houk K. N.; Krauss I. J. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013, 135, 82–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Kennedy J. W. J.; Hall D. G. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2002, 124, 11586–11587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Lachance H.; Lu X.; Gravel M.; Hall D. G. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2003, 125, 10160–10161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Gravel M.; Lachance H.; Lu X.; Hall D. G. Synthesis 2004, 1290–1302. [Google Scholar]; d Kim H.; Ho S.; Leighton J. L. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011, 133, 6517–6520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishiyama T.; Ahiko T.; Miyaura N. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2002, 124, 12414–12415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerrard W.; Lappert M. F.; Shafferman R. J. Chem. Soc. 1958, 3648–3652. [Google Scholar]

- Bhatt M. V.; Kulkarni S. U. Synthesis 1983, 1983, 249–282. [Google Scholar]

- Evidence for dimeric boron carboxylates:; a Brown H. C.; Stocky T. P. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1977, 99, 8218–8226. [Google Scholar]; b Yalpani M.; Boese R.; Seevogel K.; Kouster R. J. Chem. Soc., Dalton Trans. 1993, 47–50. [Google Scholar]; c Chakraborty D.; Rodriguez A.; Chen E. Y. X. Macromolecules 2003, 36, 5470–5481. [Google Scholar]; d Dell’Amico D. B.; Calderazzo F.; Labella L.; Marchetti F. Inorganic Chemistry 2008, 47, 5372–5376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e Schäfer A.; Saak W.; Haase D.; Müller T. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2012, 51, 2981–2984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ligand-exchange catalysis examples:; a Chong J. M.; Shen L.; Taylor N. J. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2000, 122, 1822–1823. [Google Scholar]; b Wu T. R.; Chong J. M. Org. Lett. 2005, 8, 15–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Lou S.; Moquist P. N.; Schaus S. E. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006, 128, 12660–12661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d Lou S.; Moquist P. N.; Schaus S. E. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007, 129, 15398–15404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e Wu T. R.; Chong J. M. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007, 129, 4908–4909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; f Lou S.; Schaus S. E. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008, 130, 6922–6923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; g Barnett D. S.; Moquist P. N.; Schaus S. E. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2009, 48, 8679–8682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; h Le P. Q.; Nguyen T. S.; May J. A. Org. Lett. 2012, 14, 6104–6107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gesinski M. R.; Tadpetch K.; Rychnovsky S. D. Org. Lett. 2009, 11, 5342–5345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colobert F.; Kreuzer T.; Cossy J.; Reymond S.; Tsuchiya T.; Ferrié L.; Marko I. E.; Jourdain P. Synlett 2007, 2007, 2351–2354. [Google Scholar]

- Amoroso J. W.; Borketey L. S.; Prasad G.; Schnarr N. A. Org. Lett. 2010, 12, 2330–2333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neumaier J.; Maier M. E. Synlett 2011, 2011, 187–190. [Google Scholar]

- Palmer C.; Morra N. A.; Stevens A. C.; Bajtos B.; Machin B. P.; Pagenkopf B. L. Org. Lett. 2009, 11, 5614–5617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lebel H.; Paquet V. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2003, 126, 320–328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly B. D.; Allen J. M.; Tundel R. E.; Lambert T. H. Org. Lett. 2009, 11, 1381–1383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miura K.; Okajima S.; Hondo T.; Nakagawa T.; Takahashi T.; Hosomi A. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2000, 122, 11348–11357. [Google Scholar]

- Shen Z.-L.; Yeo Y.-L.; Loh T.-P. J. Org. Chem. 2008, 73, 3922–3924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hay M. B.; Hardin A. R.; Wolfe J. P. J. Org. Chem. 2005, 70, 3099–3107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamaru Y.; Kimura M. Org. Synth. 2006, 83, 88–96. [Google Scholar]

- Chandrasekhar S.; Mahipal B.; Kavitha M. J. Org. Chem. 2009, 74, 9531–9534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimura M.; Ezoe A.; Mori M.; Iwata K.; Tamaru Y. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006, 128, 8559–8568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becke A. D. J. Chem. Phys. 1993, 98, 5648–5652. [Google Scholar]

- Lee C.; Yang W.; Parr R. G. Phys. Rev. B 1988, 37, 785–789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vosko S. H.; Wilk L.; Nusair M. Can. J. Phys. 1980, 58, 1200–1211. [Google Scholar]

- Stephens P. J.; Devlin F. J.; Chabalowski C. F.; Frisch M. J. J. Phys. Chem. 1994, 98, 11623–11627. [Google Scholar]

- Grimme S.; Antony J.; Ehrlich S.; Krieg H. J. Chem. Phys. 2010, 132, 154104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grimme S.; Ehrlich S.; Goerigk L. J. Comput. Chem. 2011, 32, 1456–1465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becke A. D.; Johnson E. R. J. Chem. Phys. 2005, 123, 154101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson E. R.; Becke A. D. J. Chem. Phys. 2005, 123, 024101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson E. R.; Becke A. D. J. Chem. Phys. 2006, 124, 174104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaefer A.; Huber C.; Ahlrichs R. J. Chem. Phys. 1994, 100, 5829–5835. [Google Scholar]

- Ribeiro R. F.; Marenich A. V.; Cramer C. J.; Truhlar D. G. J. Phys. Chem. B 2011, 115, 14556–14562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frisch M. J.et al. Gaussian 09, Rev. D.01 and B.01; Gaussian, Inc.: Wallingford, CT, 2013. and 2010. See the Supporting Information for the full citation. [Google Scholar]

- Legault C. Y. “CYLView 1.0b”, Université de Sherbrooke, 2009. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.