Abstract

Objective

Experimental and clinical data support the inhibitory effect of testosterone on breast tissue and breast cancer. However, testosterone is aromatized to estradiol, which exerts the opposite effect. The aim of this study was to determine the effect of testosterone, combined with the aromatase inhibitor anastrozole, on a hormone receptor positive, infiltrating ductal carcinoma in the neoadjuvant setting.

Methods

To determine clinical response, we obtained serial ultrasonic measurements and mammograms before and after therapy. Three combination implants—each containing 60 mg of testosterone and 4 mg of anastrozole—were placed anterior, superior, and inferior to a 2.4-cm tumor in the left breast. Three additional testosterone-anastrozole implants were again placed peritumorally 48 days later.

Results

By day 46, there was a sevenfold reduction in tumor volume, as measured on ultrasound. By week 13, we documented a 12-fold reduction in tumor volume, demonstrating a rapid logarithmic response to intramammary testosterone-anastrozole implant therapy, equating to a daily response rate of 2.78% and a tumor half-life of 23 days. Therapeutic systemic levels of testosterone were achieved without elevation of estradiol, further demonstrating the efficacy of anastrozole combined with testosterone.

Conclusions

This novel therapy, delivered in the neoadjuvant setting, has the potential to identify early responders and to evaluate the effectiveness of therapy in vivo. This may prove to be a new approach to both local and systemic therapies for breast cancer in subgroups of patients. In addition, it can be used to reduce tumor volume, allowing for less surgical intervention and better cosmetic oncoplastic results.

Key Words: Testosterone, Anastrozole, Breast cancer, Intramammary, Neoadjuvant

The biological effect of testosterone on the androgen receptor (AR) prevents the proliferation of breast tissue and inhibits the growth of breast cancer cells.1-4 Since the 1940s, testosterone and testosterone pellet implants have been used to treat advanced breast cancer as well as menopausal symptoms in breast cancer survivors.5,6 However, in breast cancer tumors, both malignant epithelial cells and surrounding fibroblasts overexpress aromatase, increasing local estrogen production, which subsequently stimulates cancer cell growth.7,8

We have previously demonstrated that two 6.4 × 3.1–mm subcutaneous implants—each containing 4 mg of anastrozole combined with 60 mg of testosterone—were able to provide therapeutic levels of testosterone without elevation of estradiol (E2) levels in breast cancer survivors.9 We have also documented both the safety and the efficacy of this combination therapy in breast cancer survivors and in women without breast cancer, including a reduction in the incidence of breast cancer.9-11

This combination testosterone-anastrozole (T + A) implant therapy, delivered locally (intramammary/peritumorally) in the neoadjuvant setting, has several theoretical advantages, including higher doses of both testosterone and the aromatase inhibitor anastrozole being delivered directly to the tumor. With increasing monetary constrictions on funding of large trials, the neoadjuvant/presurgical setting will probably become increasingly useful in evaluating clinical response to novel therapies.12

METHODS

The patient is a 90-year-old G2P2 woman with a history of menarche at age 14, natural menopause at age 43, and a family history of breast cancer (grandmother). She was found to have a suspicious left breast lesion on CT scan of the chest, which was ordered after a fall.

Subsequent mammogram on December 7, 2012 revealed a 2.4-cm-deep obscured mass in the posterior central left breast, consistent with CT findings. Ultrasound (US) of the left breast revealed a 2.4 × 2.3 × 1.7–cm (ie, tumor volumea of 5.12 cm3) suspicious mass in the subareolar 3-o’clock position. US-guided core biopsy was performed, revealing grade 2 infiltrating ductal carcinoma (estrogen receptor [ER]–positive, progesterone receptor [PR]–positive, AR-positive, and HER2-negative).

An oncology consultation recommended 20 mg of tamoxifen daily. The patient refused surgical intervention but complied with tamoxifen therapy from December 2012 through March 2013.

She was seen and evaluated at the Millennium Clinic on March 1, 2013. The patient was alert and oriented and in good health, with no history of diabetes or cardiovascular disease. Medical history was significant for depression, mildly elevated blood pressure, postherpetic pain syndrome, and elevated lipid levels. There was a slight thickening in the left breast at the 3-o’clock position at the areolar border, extending under the nipple-areola complex. There was no palpable axillary adenopathy and no skin or nipple changes. Initial medication list was extensive and included duloxetine HCl, lisinopril, atorvastatin, omeprazole, temazapam, aspirin, pregabalin, tamoxifen, and supplements.

US performed in the office reconfirmed the presence of a 2.3-cm-deep left subareolar mass, unchanged from her previous US on December 7, 2012.

A written informed consent form was obtained, and the patient agreed to intramammary placement of T + A implants. In addition, the patient was informed that the combination T + A implant was prescribed by a physician for a purpose for which it has not been specifically approved (ie, “off-label” use).

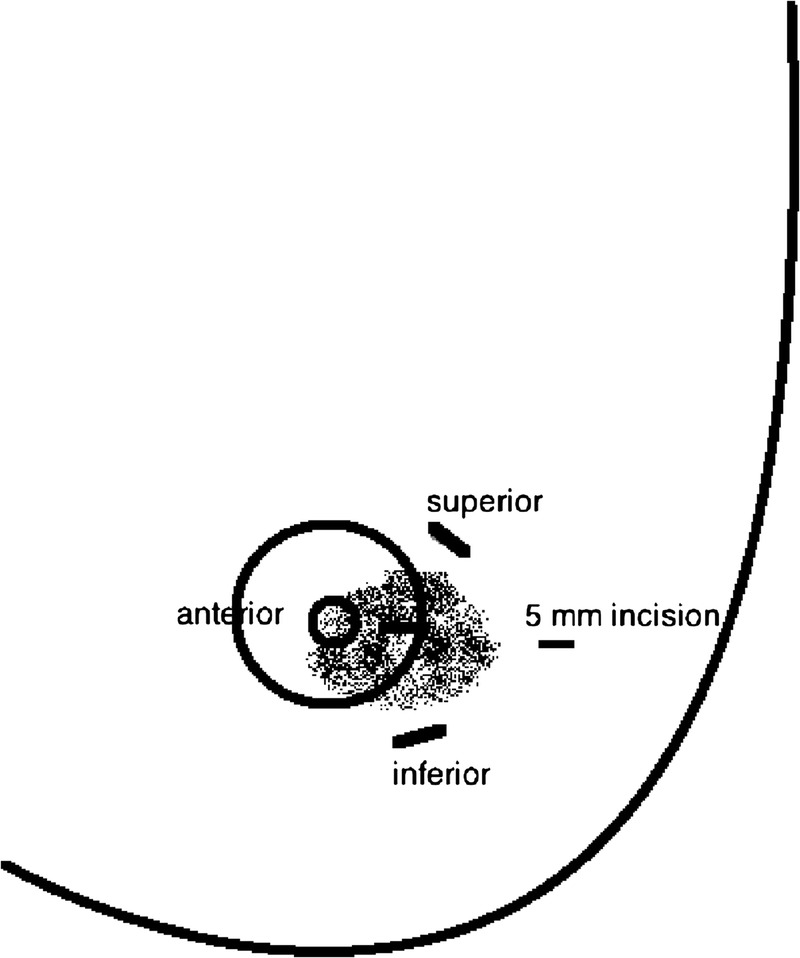

Through a 5-mm lateral incision, three compounded 60 mg T + 4 mg A pellets were implanted into the breast tissue surrounding the tumor approximately 1 cm superior to, 1 cm inferior to, and anterior to the subareolar tumor through a disposable trocar (Fig. 1). Tamoxifen was discontinued.

FIG. 1.

Three testosterone-anastrozole implants were inserted intramammary/peritumorally 1 cm superior to, 1 cm inferior to, and anterior to the subareolar carcinoma through a lateral 5-mm incision.

RESULTS

Follow-up examination of the left breast 2 weeks after intramammary T + A pellet implantation revealed a marked decrease in tumor size on physical examination and office US. The periareolar “thickening” was no longer palpable. By week 4, the patient’s (previously unreported) left breast pain had subsided.

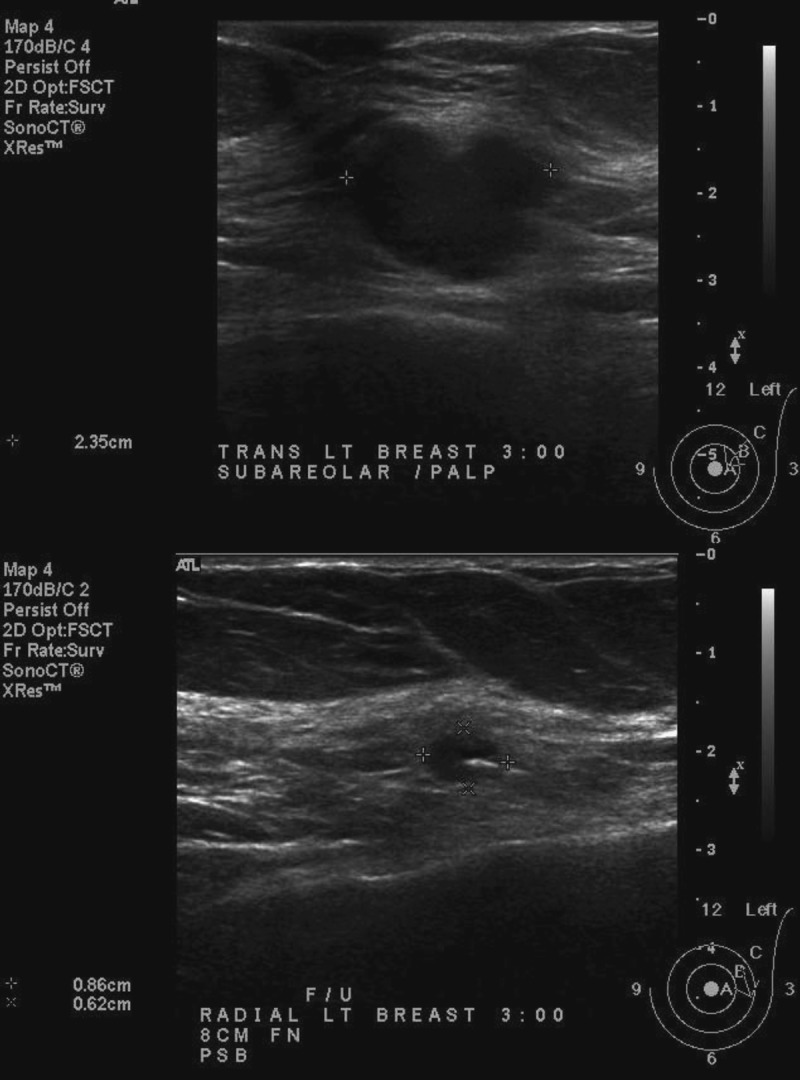

On April 16, 2013, 46 days after intramammary T + A therapy, follow-up left breast mammogram and US, performed at the original imaging center by the same radiologist, revealed a significant decrease in tumor mass size. On US, the tumor measured 1.6 × 1.1 × 0.8 cm, with a tumor volume of 0.74 cm3, indicating a sevenfold reduction in tumor volume compared with 5.12 mL on December 7, 2012.

Three additional implants (ie, total dose of 180 mg T + 12 mg A) were again placed peritumorally in the left breast on April 18, 2013.

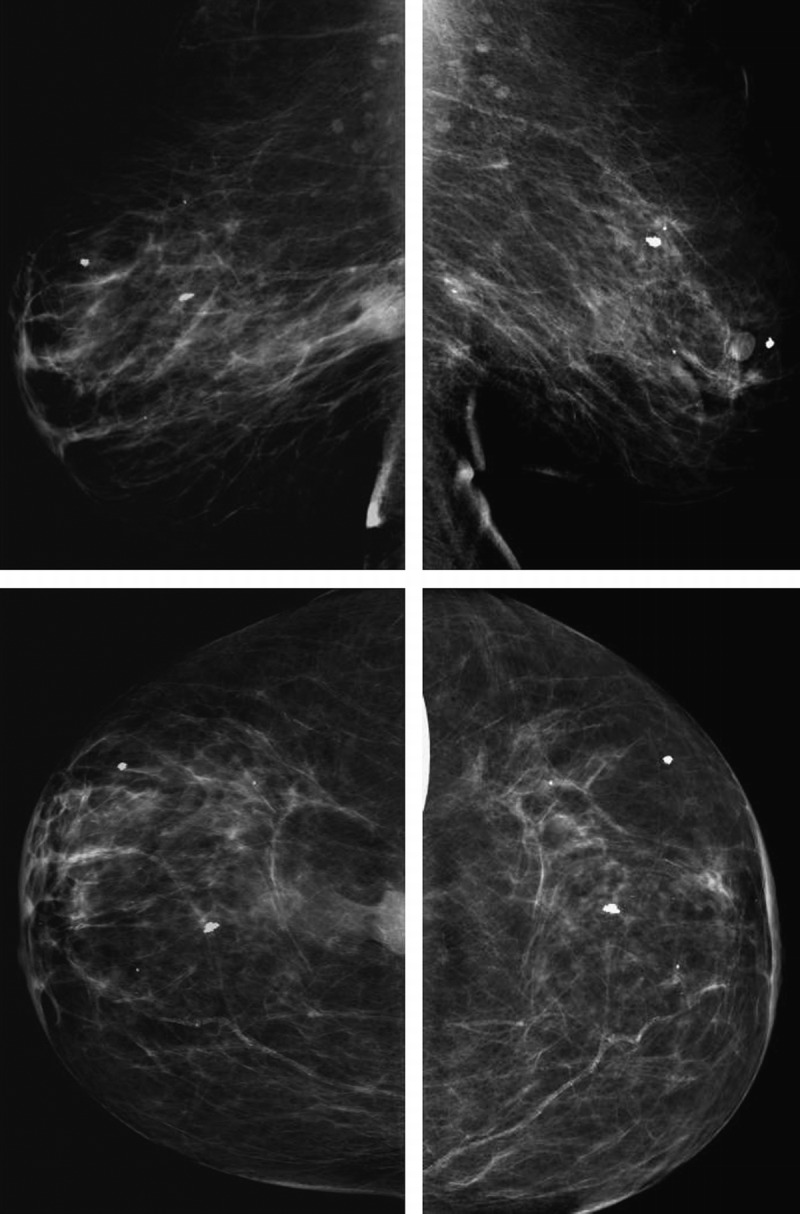

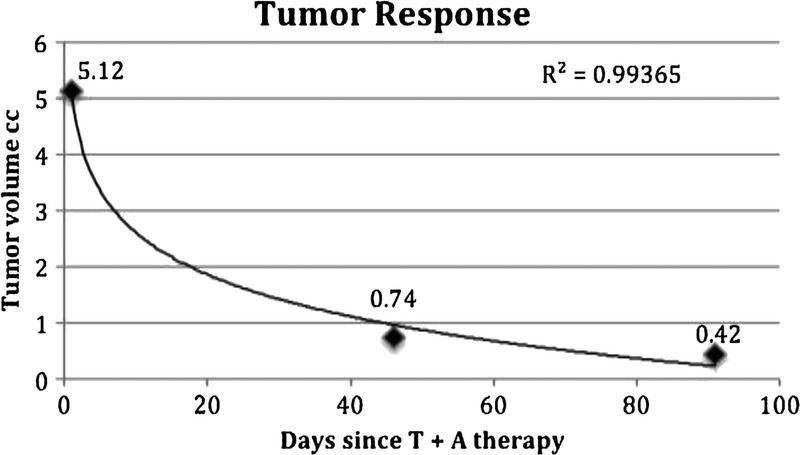

Follow-up mammogram (Fig. 2) and US (Fig. 3) on week 13, again performed at the same radiology facility, revealed that the size of the carcinoma had continued to decrease, measuring 1.5 × 0.8 × 0.6 cm on US, with a tumor volume of 0.42 cm3. This 12-fold reduction in tumor volume from the original measurement equates to a 2.78% decrease per day (after therapy) and a half-lifeb of 23 days. The logarithmic response of the carcinoma to T + A therapy is evidenced by an R2 value greater than 0.99 (Fig. 4).

FIG. 2.

Left breast mammogram: mediolateral oblique (MLO) view on December 7, 2012 (top left); MLO view on May 31, 2013 (top right); craniocaudal (CC) view on December 7, 2012 (bottom left); CC view on May 31, 2013 (bottom right). There was a significant decrease in the size of a biopsy-proven malignancy 13 weeks after testosterone-anastrozole implant therapy.

FIG. 3.

Left breast subareolar biopsy-proven malignancy. Baseline ultrasound performed on December 7, 2012 (top) compared with follow-up ultrasound performed on May 31, 2013 (bottom) demonstrates a significant reduction in tumor size 13 weeks after testosterone-anastrozole (T + A) implant therapy. Baseline tumor size was reconfirmed on office ultrasound before therapy on March 1, 2013 (image not shown).

FIG. 4.

Logarithmic decline in tumor volume (cm3) measured by ultrasound (R2 > 0.99).

In addition, many of the patient’s symptoms, including memory loss, physical fatigue, urinary incontinence, sleep disturbance, depression, and pain, improved with testosterone therapy. Adequate serum levels of testosterone, without elevation of E2, were confirmed on day 7 postinsertion (testosterone, 473 ng/dL; E2 <5 pg/mL), day 46 postinsertion (testosterone, 366 ng/dL; E2 <5 pg/mL), and again on day 7 after the second intramammary insertion procedure (testosterone, 345 ng/dL; E2 <5 pg/mL). Interestingly, the patient was able to discontinue several medications in addition to tamoxifen, including duloxetine HCl, lisinopril, and atorvastatin. There have been no adverse drug events with therapy. The patient “feels better than she has in years,” is no longer using a walker, and is driving her car again. She continues to refuse any surgical intervention.

Follow-up US and mammogram are scheduled for September 2013, 6 months from the initial intramammary T + A pellet insertion. If a residual mass is present, an US-guided core biopsy will be performed to reevaluate tumor characteristics and hormone receptor status. The patient will be continued on intramammary therapy (180 mg T + 12 mg A) for a minimum of 1 year after complete clinical response. She will then continue to be treated with T + A implant therapy, possibly at alternate insertion sites.

DISCUSSION

Although there was virtually no response to oral tamoxifen therapy between December 2012 and March 2013 (as evidenced by tumor measurements on office US), our patient manifested a rapid clinical response to intramammary T + A therapy by 46 days, continuing through week 13. This was particularly evident when we compared three-dimensional tumor volumes over time, calculated using the ellipsoid formula,a which has been shown to be superior to using only the greatest (tumor) diameter.12

This innovative pharmacologic combination (T + A), unique delivery method (sustained-release implant), and unique delivery location (intramammary and peritumorally) in the neoadjuvant setting has many potential advantages both for research and for the local and systemic therapy of breast cancer.

The combination of testosterone delivered simultaneously with anastrozole allows the beneficial effects of testosterone on the AR and simultaneously prevents aromatization to E2. Testosterone is beneficial for immune function and treats many systemic symptoms, adverse effects of cancer therapies, and the breast cancer itself.1-4,9,13,14 The sustained-release combination implant ensures continuous, simultaneous delivery and absorption of both active ingredients locally at the tumor site while maintaining consistent therapeutic systemic levels of testosterone without elevating E2. We have previously published data on the safety and efficacy of these doses of testosterone and have shown that pharmacologic doses of testosterone—as evidenced by serum levels several fold higher than endogenous levels measured on week 4 (299.36 ± 107.34 ng/dL) and before reimplantation (171.43 ± 73.01 ng/dL)—produce a physiologic (therapeutic) effect and are not associated with adverse events.15 The only expected androgenic adverse effect in our patients has been a slight increase in facial hair. The safety of the 180-mg testosterone implant has also been confirmed in historic studies, where doses from 150 to 225 mg were routinely prescribed and doses up to 800 to 1,800 mg were safely used in the long term to treat metastatic breast cancer and female-to-male transgender patients.5,6,15,16 Contrarily, there is a lack of evidence to support that serum ranges from endogenous production should be extrapolated to exogenous therapy or used to determine implant dosing in lieu of “clinical efficacy” and “adverse effects.” In addition to testosterone, the androgen precursors dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate (DHEAS) and androstenedione, found in much greater concentrations (up to 103-fold) than testosterone, also decline with age. We have found that higher serum levels of testosterone (supplied by the implant) are necessary to provide adequate amounts of testosterone to the AR, replacing not only testosterone but also the significant contributions of DHEAS and androstenedione to bioavailable testosterone.15

Unlike oral medication, patient compliance is not an issue with implanted pellets. Furthermore, the implant allows for lower, more efficient, and effective dosing of anastrozole. Subcutaneous delivery avoids the gastrointestinal tract and subsequent gastrointestinal adverse effects, including nausea, vomiting, and pain. There is no first-pass effect and no adverse effect on the liver or clotting factors.

The intramammary location is particularly unique in that it allows differential dosing. High doses of both testosterone and anastrozole are delivered locally, directly targeting the tumor, whereas lower therapeutic systemic levels are achieved. This is in direct contrast to neoadjuvant therapy by other delivery methods, including oral or intravenous, where higher systemic levels are necessary to deliver adequate dosing to the breast tissue/tumor site, resulting in greater systemic adverse effects and toxicities and less effective local therapy.

The neoadjuvant/presurgical setting also allows identification of responders (vs nonresponders) and early evaluation and documentation of the effectiveness of therapy.17,18 Moreover, in larger tumors, this therapy may allow for breast-conserving surgical operation, with improved oncoplastic cosmetic results.

This patient and several others who have responded to T + A therapy were AR-positive, consistent with testosterone effect on the AR.1-4 Interestingly, an 81-year-old patient with a clinical stage 2, ER-positive, PR-positive, AR-positive tumor, subsequently treated with T + A intramammary therapy, is also responding, although at a slower rate (1.87% per day, half-life of 37 d), with a logarithmic decline in tumor volume (R2 = 0.96). In addition, her palpable adenopathy is also responding to therapy.

In the future, it would be interesting to monitor response to T + A therapy among “triple-negative” (ER-negative, PR-negative, and HER2-negative) patients, who may be AR-positive. Contraindications to this therapy have not been recognized; however, caution should be exercised in ER-negative, HER2-positive patients; one study has shown that AR positivity was “associated” with poorer prognosis.19 Although an AR-negative tumor may not respond as well to this therapy, patients may still benefit from testosterone’s anabolic effects on bone density, as well as testosterone’s immunostimulatory, anti-inflammatory, and pain-relieving properties. Unlike higher-dose oral aromatase inhibitors, which can secondarily increase gonadotropin-releasing hormone and subsequently stimulate the ovary to reproduce estrogens, low-dose parenteral anastrozole, in combination with testosterone, may also prove to be appropriate in premenopausal hormone receptor–positive patients. However, until further studies are performed, older postmenopausal patients with hormone-positive tumors are considered to be the most appropriate candidates for this novel treatment.

The combination implant is also cost-effective, providing 2 to 3 months of therapy with a single, minimally invasive, 2-minute procedure at a cost of approximately US$2.00 to US$3.00 per day. In the future, this therapy may be used in conjunction with other endocrine therapies (such as tamoxifen) or sulfatase inhibitors, which prevent hydrolysis of estrone sulfate and DHEAS, both of which can be reduced to steroids with estrogenic properties in a low-estrogen environment.20

CONCLUSIONS

We have shown that this combination T + A therapy was well tolerated by this 90-year-old patient and effectively treated her AR-positive breast cancer. Neoadjuvant endocrine therapy for a grade 2, hormone receptor–positive breast cancer using intramammary T + A therapy resulted in a rapid clinical response (ie, 12-fold reduction in tumor volume within 3 mo).

A neoadjuvant study option allows the observation and documentation of clinical response and, if followed by surgical excision, the biology of tumor response. In addition, this therapy may allow for fewer surgical operations and improved oncoplastic results. Further research is needed to delineate the role of sustained-release T + A in both the prevention and the treatment of breast cancer. In the future, this combination may have the potential for both systemic and local therapies for breast cancer in subgroups of patients, possibly eliminating surgical operation, radiation therapy, and adverse effects of oral medication.

Footnotes

aEllipsoid formula: 4/3π (a/2 × b/2 × c/2).

bLogarithmic half-life equation: x = log(0.5) / log(1 − 0.0278).

Funding/support: None.

Financial disclosure/conflicts of interest: None reported.

REFERENCES

- 1. Dimitrakakis C. Androgens and breast cancer in men and women. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am 2011; 40: 533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Labrie F, Labrie C, Bélanger A, Simard J, Lin SX, Pelletier G. Endocrine and intracrine sources of androgens in women: inhibition of breast cancer and other roles of androgens and their precursor dehydroepiandrosterone. Endocr Rev 2003; 24: 152- 182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Hickey TE, Robinson JLL, Carroll JS, Tilley WD. Minireview: The androgen receptor in breast tissues: growth inhibitor, tumor suppressor, oncogene? Mol Endocrinol 2012; 26: 1252- 1267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Eigėlienė N, Elo T, Linhala M, Hurme S, Erkkola R, Härkönen P. Androgens inhibit the stimulatory action of 17β-estradiol on normal human breast tissue in explant cultures. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2012; 97: E1116- E1127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Greenblatt RB, Suran RR. Indications for hormonal pellets in the therapy of endocrine and gynecic disorders. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1949; 57: 294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Segaloff A, Gordon D, Horwitt BN, Schlosser JV, Murison PJ. Hormonal therapy in cancer of the breast, 1: the effect of testosterone propionate therapy on clinical course and hormonal excretion. Cancer 1951; 4: 319- 323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Simpson ER. Sources of estrogen and their importance. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol 2003; 86: 225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Bulun SE, Lin Z, Zhao H, et al. Regulation of aromatase expression in breast cancer tissue. Ann N Y Acad Sci 2009; 1155: 121- 131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Glaser R. Subcutaneous testosterone-anastrozole implant therapy in breast cancer survivors. Am Soc Clin Oncol Breast Cancer Symp 2010; D: 221. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Glaser R, Dimitrakakis C. 14 Subgroups of patients treated with an aromatase inhibitor (anastrozole) delivered subcutaneously in combination with testosterone. 9th Eur Congr Menopause Andropause. 2012; A424: 0001- 00048. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Glaser RL, Dimitrakakis C. Reduced breast cancer incidence in women treated with subcutaneous testosterone, or testosterone with anastrozole: a prospective, observational study [epub ahead of print]. Maturitas 2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Wapnir IL, Wartenberg DE, Greco RS. Three dimensional staging of breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat 1996; 41: 15- 19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Glaser R, York AE, Dimitrakakis C. Beneficial effects of testosterone therapy in women measured by the validated Menopause Rating Scale (MRS). Maturitas 2011; 68: 355- 361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Malkin CJ, Pugh PJ, Jones RD, Kapoor D, Channer KS, Jones TH. The effect of testosterone replacement on endogenous inflammatory cytokines and lipid profiles in hypogonadal men. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2004; 89: 3313- 3318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Glaser R, Kalantaridou S, Dimitrakakis C. Testosterone implants in women: pharmacological dosing for a physiologic effect. Maturitas 2012; 74: 179- 184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Segaloff A. Hormone treatment of breast cancer. JAMA 1975; 234: 1175- 1177. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Geisler J, Smith I, Miller W. Presurgical (neoadjuvant) endocrine therapy is a useful model to predict response and outcome to endocrine treatment in breast cancer patients. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol 2012; 131: 93- 100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Dowsett M, Smith I, Robertson J, et al. Endocrine therapy, new biologicals, and new study designs for presurgical studies in breast cancer. JNCI Monogr 2011; 2011: 120- 123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Park S, Koo JS, Kim MS, et al. Androgen receptor expression is significantly associated with better outcomes in estrogen receptor–positive breast cancers. Ann Oncol 2011; 22: 1755- 1762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Purohit A, Woo LW, Potter BV. Steroid sulfatase: a pivotal player in estrogen synthesis and metabolism. Mol Cell Endocrinol 2011; 340: 154- 160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]