Abstract

Foot pain is a common orthopedic condition that can have an impact on health-related quality of life. The evaluation of plantar hindfoot pain begins with history and physical examination. Imaging modalities, standard radiographs, sonography, MR, CT are often utilized to clarify the diagnosis. The article is a detailed description of the sonographic evaluation of the plantar fascia and its disorders as well as the common etiologies in the differential diagnosis of plantar fasciopathy.

Keywords: Sonography, Plantar fasciopathy, Plantar aponeurosis, Lateral cord, Hindfoot, Heel pain

Riassunto

Il dolore al piede è una condizione ortopedica comune, che può avere un impatto sulla qualità della vita legata alla salute. La valutazione del dolore del retro-piede inizia con l’anamnesi e con l’esame fisico. Le varie modalità di imaging, radiografie standard, ecografia, risonanza magnetica, TC, sono spesso utilizzate per chiarire la diagnosi. L’articolo è una descrizione dettagliata della valutazione ecografica della fascia plantare e dei suoi disturbi, nonché delle patologie che più frequentemente entrano nella diagnosi differenziale con le malattie della fascia plantare.

Introduction

Foot pain is a common orthopedic condition that can have an impact on health-related quality of life with population-based studies demonstrating a prevalence of up to 28 % [1–3]. Plantar fasciopathy is a common cause of foot pain in adults and comprises over one million outpatient visits annually [4]. However, other causes of heel pain should always be considered in the differential diagnosis of plantar fasciopathy as effective treatment of heel pain hinges upon an accurate diagnosis. The evaluation of plantar hindfoot pain begins with a detailed history, physical examination, and standard radiographs. Advanced imaging modalities, such as sonography, MR, or CT are often utilized to clarify the diagnosis especially when heel pain becomes recalcitrant or recurrent.

High-resolution sonography is an ideal imaging choice for evaluation of plantar hindfoot pain since it readily evaluates the plantar fascia as well as other surrounding structures that may reveal an alternative cause of pain [5]. Other advantages of sonography include its cost effectiveness, lack of ionizing radiation, availability, and the real-time nature of the sonographic examination. The following is a detailed description of the sonographic evaluation of the plantar fascia and its disorders as well as the common etiologies in the differential diagnosis of plantar fasciopathy.

US of the plantar aponeurosis

Normal anatomy and US appearance

The plantar aponeurosis has both a structural and functional role in facilitating the foot’s ability to effectively perform in human propulsion. Structurally, it has a fundamental role in foot biomechanics, including supporting the medial longitudinal arch and dissipating the forces and stresses of the foot during gait or other loading conditions. More recently, the plantar fascia has been postulated to play an important role in proprioception and peripheral motor coordination. [6, 7]. The plantar aponeurosis comprises three cords: central, medial, and lateral. The central cord is the most clinically significant. It originates from the plantar aspect of the posteromedial calcaneal tuberosity, where it conforms to the convexity of the underlying calcaneus (Fig. 1a–c) [8]. The proximal third of the central cord is triangular with the apex posterior (Fig. 1b, c). As it travels distally, it becomes thinner and wider, while also adhering to the underlying flexor digitorum brevis muscle. At approximately, the mid-metatarsal level the central cord divides into five diverging bands that have a complex array of attachments to their respective toes, including the palmar plates, flexor tendons, interosseous ligament, and transverse metatarsal ligament [8, 9].

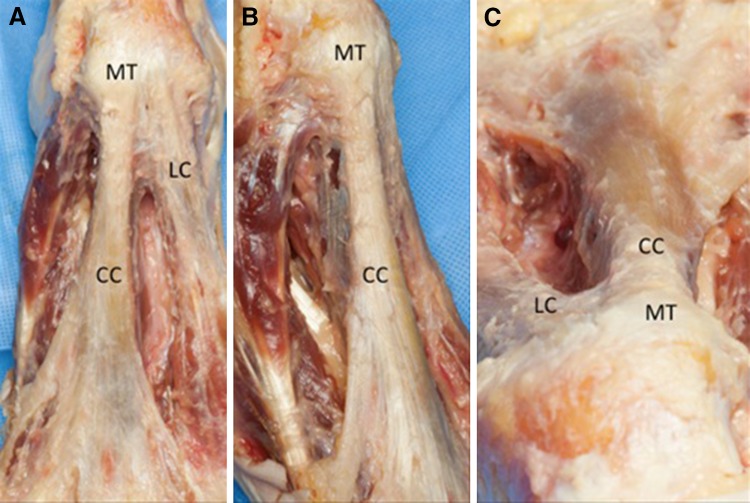

Fig. 1.

Cadaveric dissection of the central cord of the plantar aponeurosis. Plantar view (a), plantar oblique view (b), and plantar axial view (c) of the central cord (CC) showing its origin from the medial tubercle of the calcaneus (MT). Note that the central cord conforms to the bony contour of the medial tubercle. The proximal third of the central cord has a triangular appearance with the apex plantar. More distally, the central cord widens and thins as it divides into five diverging bands. LT lateral cord of the plantar fascia

The medial cord also arises from the medial calcaneal tuberosity and travels as a thin aponeurotic band that forms the covering fascia of the abductor hallucis muscle [8]. Because the medial cord is the least clinically significant of the three cords, further anatomic details are beyond the scope of this article.

The lateral cord of the plantar fascia arises from the lateral aspect of the medial calcaneal tuberosity where it partially blends with the origin of the underlying abductor digiti minimi muscle and the lateral aspect of the central cord (Fig. 1a) [8]. The lateral cord travels distally towards the base of the fifth metatarsal tuberosity superficial to the abductor minimi muscle where it shares an insertion with the peroneus brevis tendon on the tuberosity of the base of the fifth metatarsal.

Ultrasonography can effectively evaluate the central cord of the plantar aponeurosis starting at the medial tuberosity of the calcaneus and following it distally. The central cord appears as homogenous hyperechoic fibrillar structure that is thick and triangular proximally and thins as one scans distally (Fig. 2a–c). At its origin on the medial tuberosity, the deep fibers of the central cord assume an oblique orientation at their insertion and thus may appear hypoechoic as a result of anisotropy (Fig. 2b). Just distal to its insertion on to the medial tuberosity, the central cord is thick and triangular with maximal thickness approximately 3–4 mm [5, 10, 11]. As one scans distally, the central cord becomes thinner on long axis view, but wider in the short axis plane.

Fig. 2.

Normal sonogram of the central cord of the plantar fascia. a Extended long axis sonogram of the central cord of the plantar fascia (CC) that arises from the medial calcaneal tuberosity (MT) and travels distally as a homogenous hyperechoic fibrillar band that overlies the flexor digitorum brevis muscle (FDB). b Close-up image of the attachment of the central cord (CC) showing the oblique orientation of the fibers as they insert on to the medial calcaneal tuberosity (MT). c Short axis sonogram of the central cord of the plantar fascia (white arrowheads) at its insertion on to the medial calcaneal tuberosity (MT). Note how the central cord conforms to the underlying calcaneus

Plantar fasciopathy

The etiology of plantar fasciopathy is primarily due to mechanical overload, although the pathogenesis is poorly understood and likely multifactorial in nature. Plantar fasciopathy classically involves the proximal third of the central cord of the plantar aponeurosis. However, distal plantar fasciopathy has been recognized as a cause of recalcitrant plantar heel pain [12]. Patients with proximal plantar fasciopathy usually describe a dull aching pain in the plantar hindfoot area, often directly over the medial calcaneal tubercle. In addition, patients often experience a sharp pain with the first few steps in the morning or after periods of inactivity. Histologic findings associated with plantar fasciopathy, include collagen necrosis, angiofibroblastic hyperplasia, chondroid metaplasia, and calcifications [13, 14].

The characteristic sonographic findings of proximal plantar fasciopathy, include hypoechoic thickening of the plantar fascia, loss of fibrillar echotexture, and loss of fascial edge sharpness (Figs. 3a, b). Other sonographic findings of proximal plantar fasciopathy include cortical irregularity of the calcaneus, often with an associated enthesophyte, and perifascial edema in acute cases [10, 11, 15–17]. It is generally accepted that a plantar aponeurosis thickness of >4 mm is consistent with plantar fasciopathy, although a minority of individuals without proximal plantar fasciopathy can have a normally large central aponeurosis [9, 11, 18]. Comparison with the contralateral side as well as other characteristic findings of plantar fasciopathy can help distinguish a normally large plantar fascia from a thickened one due to fasciopathy. The use of Doppler imaging is often normal with plantar fasciopathy, but rarely may demonstrate varying degrees of hyperemia in the proximal plantar aponeurosis and surrounding tissue [19]. Ultrasound also has a role in the management of plantar fasciopathy by guiding local injection of steroids [20–22], extracorporeal shock-wave therapy [23], or needle tenotomy [24].

Fig. 3.

Sonogram of proximal plantar fasciopathy. Long axis (a) and short axis (b) sonograms showing marked hypoechoic thickening of the proximal central cord of the plantar fascia with several foci of complete loss of fibrillar echotexture. In addition, note the loss of fascial edge sharpness (white arrowheads) and cortical irregularity with large enthesophyte (asterisk) of the underlying medial tubercle of the calcaneus (MT)

The sonographic appearance of distal plantar fasciopathy includes fusiform hypoechoic thickening of the distal central cord with loss of normal fibrillar echotexture (Fig. 4a, b). Typically, the entire width of the aponeurosis is thickened that may help distinguish this entity from that of a plantar fibroma that may have a similar sonographic appearance.

Fig. 4.

Sonogram of distal plantar fasciopathy of the central cord of the plantar fascia. Long axis (a) and short axis (b) sonograms of the distal central cord of the plantar fascia shows full thickness fusiform hypoechoic thickening (between calipers) with alteration, although not complete loss of fibrillar echotexture. Note that the thickening is completely contained with in the fascia edges of the aponeurosis which is in contrast to plantar fibromatosis where the fibroma will typically extend beyond the superficial border of the aponeurosis

Plantar fascia tear

Tears of the plantar fascia can be partial or complete. Partial plantar fascia tears can be hard to differentiate from severe fasciopathy. A history of a sudden tearing sensation or sonographic demonstration of separation of the central cord during dynamic dorsiflexion of the ankle and great toe can aid in distinguishing fasciopathy from a partial tear (Fig. 5a, b) [5, 25].

Fig. 5.

Sonogram of a partial tear of the central cord of the plantar fascia with corresponding MR. Long axis sonogram (a) with corresponding T2-weighted MR (c) shows hypoechoic thickening, loss of normal fibrillar echotexture, and loss of sharp borders characteristic of proximal plantar fasciopathy. In addition, there is a focus of complete loss of echotexture (solid arrowhead) that widened with dynamic dorsiflexion of the ankle and great toe confirming the presence of a partial tear. Short axis sonogram (b) and corresponding T2-weighted MR (d) showing the partial tear. Note the cortical irregularity of the medial calcaneal tubercle (MT) suggestive of an underlying chronic proximal plantar fasciopathy

Complete rupture of the central cord of the plantar fascia is relatively uncommon and is often associated with long standing plantar fasciopathy or a recent corticosteroid injection [26, 27]. Spontaneous complete ruptures are often preceded by a popping sensation and acute onset of pain, edema, and tenderness [28]. Confirmation of a complete rupture is best achieved by demonstrating widening of the gap between the two fascial ends with dynamic dorsiflexion of the ankle and great toe (Fig. 6) [17].

Fig. 6.

Sonogram of a complete plantar fascia tear. Long axis sonogram of a complete tear of the proximal central cord of the plantar fascia. Note that the central cord has torn and retracted (arrowheads) from the medial calcaneal tubercle (MT)

Post-plantar fascia release

Surgical fasciotomy may be indicated in patients with severe plantar fasciopathy that have been refractory to non-operative treatments. Surgical fasciotomy can be partial or complete, and generally is performed just distal to its origin on the calcaneus. Partial fasciotomies, whether open or endoscopic, involve releasing generally 25–50 % of the medial central cord. Causes of foot pain after plantar fasciotomy can be grouped into several pathologic processes [29]. The first is problems arising from the plantar fascia, mainly recurrent or persistent plantar fasciopathy (Fig. 7a, b). Acute plantar fascia rupture can also occur in patients, who have had a partial release. Pain may also arise from medial arch instability, particularly when the plantar fascia has been completely released. Increased stresses on the medial arch can in turn result in pathology to the posterior tibialis and flexor digitorum longus tendons as well as the peroneal tendons. Finally, alterations in midfoot and lateral column mechanics can lead to an array of problems including stress injury to bone, midfoot arthrosis, and various soft-tissue breakdown. Sonographic evaluation of continued foot pain after surgical fasciotomy should include systemic evaluation of the plantar fascia, medial tarsal tunnel structures, peroneal tendons, and midfoot joints for signs of arthrosis.

Fig. 7.

Sonogram of a 46-year woman who is 8 months status post an open complete plantar fascia release with the return of heel pain. Long axis sonogram (a) with color Doppler imaging (b) shows complete transection of the central cord with retraction of the two ends (calipers in A) with vascularity at the proximal stump and adjacent to the medial calcaneal tuberosity (MT) suggestive of inflammatory changes most likely from direct pressure to the area

Entrapment of the first branch of the lateral plantar nerve (Baxter’s neuropathy)

Entrapment of the first branch of the lateral plantar nerve (FBLPN), also known as Baxter’s neuropathy, is a well-documented cause of heel pain and should be considered in the differential diagnosis of plantar fasciopathy. Compression of the FBLPN typically occurs in two locations. The first is between the abductor hallucis and quadratus plantae muscles where the nerve changes from a vertical to a horizontal position [30]. More distally, where the FBLPN passes anterior to the medial calcaneal tubercle, entrapment can occur as a result of a calcaneal enthesophyte or plantar fascia thickening from fasciopathy [31–34]. The FBLPN provides motor innervation to the flexor digitorum brevis, quadratus plantae, and abductor digiti minimi muscles. Innervation of the abductor digiti minimi muscle is distal to where the FBLPN passes adjacent to the medial calcaneal tuberosity and, therefore, isolated atrophy of the abductor digiti minimi muscle is a sign of compression at that location (Fig. 8a, b). Heel pain due to entrapment of the FBLPN can be difficult to establish since it can occur in isolation or coexist with plantar fasciopathy [35–38]. Furthermore, atrophy of the abductor digiti minimi muscle can be an asymptomatic finding [30, 38–40]. Recently, Presley et al., [35] demonstrated that the FBLPN can be reliably visualized at the proximal abductor hallucis–quadratus plantae interval and a sonographically guided diagnostic injection at that site may help to establish the diagnosis of FBLPN entrapment (Fig. 8c).

Fig. 8.

Sonographic evaluation of entrapment of the first branch of the lateral plantar nerve (Baxter’s neuropathy). Long axis sonogram of the abductor digit minimi muscle (ADM) (a) shows general hypoechogenicity suggestive of fatty replacement from chronic compression of the first branch of the lateral plantar nerve. For comparison, the adjacent flexor digitorum brevis muscle (FDB) (b) shows normal muscle echogenicity. c Short axis sonogram shows the first branch of the lateral plantar nerve (white arrowhead). Within the distal medial tarsal tunnel, after the tibial nerve divides into the medial and lateral plantar nerve, the first branch of the lateral plantar nerve divides from the lateral plantar nerve (white arrow) and travels in a vertical orientation towards the interval between the abductor hallucis (not shown) and the quadratus plantae (QP). At this location, an ultrasound-guided nerve block can be performed to confirm the presence of an entrapment of the first branch of the lateral plantar nerve

Plantar fibromatosis

Plantar fibromatosis or Ledderhose disease is a benign fibroblastic proliferative disorder characterized by focal nodular enlargement most commonly within the central cord of the plantar fascia. Most lesions are solitary and unilateral; however, approximately one-third of lesions are bilateral, and one-fourth of patients have multiple lesions [45].

Clinically, patients will most often present with a painless fibrous nodule easily palpated on physical examination. Occasionally, the nodule may become painful from direct pressure against the arch of the shoe. Less common causes of pain, include direct pressure of a nodule against the medial plantar nerve, inflammation within the nodule, and a nodule located at the proximal attachment of the central cord, which can mimic proximal plantar fasciopathy [5, 41–44].

The sonographic appearance of a plantar fibroma includes a hypoechoic fusiform nodular thickening within the central cord of the plantar fascia (Fig. 9a, b). Typically, the nodule is located more superficial within the aponeurosis having a predilection for the medial (60 %) versus the central region (40 %) of the cord [45]. Continuity of the nodule with the plantar fascia distinguishes it from other soft-tissue tumors [5]. Color Doppler imaging shows vascularity in cases of an inflammatory fibroma or atypical cases. No correlation has been established between the US appearance of the nodules, the duration of symptoms, and the clinical outcome [45].

Fig. 9.

Sonogram of plantar fibromatosis. Long axis (a) and short axis (b) sonogram of the central cord of the plantar fascia shows a hypoechoic fusiform nodular thickening (white arrowheads) that is located in the superficial and medial region of the central cord, the most common location. Note the lack of continuity of the fibrillar echotexture and superficial border of the central cord which helps distinguish a fibroma from distal plantar fasciopathy. FDB flexor digitorum brevis

The sonographic appearance of distal plantar fasciopathy can appear similar to that of a fibroma. An important distinguishing feature is that distal plantar fasciotomy tends to have uniform hypoechoic thickening throughout the width of the central cord, as viewed on long axis imaging, whereas plantar fibromas often involve the superficial one-half to two-thirds of the fascia and may extend beyond the superficial border.

Foreign body

The differential diagnosis of a plantar heel pain includes a foreign body since they are most commonly found within the subcutaneous fat of the plantar aspect of the foot, particularly in patients who walk barefoot (Fig. 10a, b) [10, 44]. A history of traumatic puncture is not always reported. Standard radiographs can be useful in the diagnosis, but are only able to detect radiopaque material.

Fig. 10.

Sonogram of a foreign body within the fat pad of the heel. Long axis sonogram (a) with color Doppler imaging (b) of a 53-year-old woman with plantar heel pain for 2 years and no recollection of a foreign body entering the foot. Methodical scanning revealed a 0.5 cm foreign body with the plantar heel pad of the hindfoot with superficial hyperemia. Note that there is a lack of granulomatous tissue reaction despite the chronicity of the foreign body. Ultrasound was also used to mark the location of the foreign body on the skin. Surgical excision revealed a wood sliver

Ultrasonography can assist in the diagnosis, size, and position of foreign body in relation to adjacent anatomic structures, which is especially important for detecting radiolucent structures. Foreign bodies often appear as linear hyperechoic band-like structures, and may be surrounded by granulomatous tissue that has a hypoechoic halo appearance. Surrounding hyperemia on color Doppler is frequent; especially, in more acute cases. Depending on the size of the foreign body, glass and metal may produce a posterior reverberation artifact while wood, thorns, and plastic usually demonstrate posterior acoustic shadowing [44]. A thorough, systematic approach to scanning is recommended to assist with locating foreign bodies that may be small and hidden in deeper structures. Ultrasonography can also guide percutaneous removal.

Calcaneal stress fracture

Calcaneal stress or insufficiency fractures should be considered in an individual presenting with plantar hindfoot pain. Conventional radiographs can confirm the diagnosis although in the early stages they are typically normal [46]. When radiographs are inconclusive, MRI can provide a definitive diagnosis.

Sonographic findings that should raise the suspicion of a stress fracture and prompt further imaging include irregularity of the calcaneal cortex with an adjacent hypoechoic line, which represents edema and thickening of the periosteum, and an increased vascularity on color Doppler imaging (Fig. 11) [5].

Fig. 11.

Sonogram of a calcaneal stress fracture. Long axis sonogram with color Doppler imaging of the plantar calcaneus shows hypoechoic thickening adjacent to the calcaneal cortex, corresponding to edema, and increased vascularity of the periosteum, both suggestive of a stress fracture. If radiographs do not show evidence of a calcaneal stress fracture then definitive confirmation can be achieved with MR evaluation

Rheumatoid nodule

Rheumatoid nodules are the most common extra-articular manifestation of rheumatoid arthritis and have a predilection for areas prone to repetitive microtrauma, including the heel [47]. Rheumatoid nodules range in size from 2 mm to 5 cm and clinically may be asymptomatic or result in pain from direct pressure for those located within the plantar hindfoot [47–49]. The ultrasound appearance of a rheumatoid nodule is variable, but most commonly shows a well-demarcated nonspecific hypoechoic mass with minimal vascularity (Fig. 12a, b) [50–52]. Typically, rheumatoid nodules reside close to bony surfaces, but are not commonly erosive to bone.

Fig. 12.

Sonogram of a rheumatoid nodule within the plantar fat pad of the hindfoot. Long axis (a) and short axis (b) sonogram shows a well-demarcated predominantly hypoechoic mass within the plantar fat pad. Color Doppler imaging did not reveal vascularity (not shown). Note that the rheumatoid nodule abuts the underlying calcaneus (CALC) but there are no erosive changes or periosteal reaction of the calcaneal cortex

Plantar vein thrombosis

Plantar vein thrombosis is a rare cause of plantar foot pain that can mimic acute plantar fasciopathy. Predisposing condition includes recent surgery, trauma, paraneoplastic conditions, and other hypercoagulable states. The medial and lateral plantar veins travel alongside their named arteries in the sole of the foot and unite with the great and small saphenous veins forming a single vein that runs behind the medial malleolus to become the posterior tibial vein [53]. Physical examination will reveal focal pain and soft tissue edema [54, 55]. Characteristic sonographic findings, include the absence of flow on Doppler US and one or more enlarged veins that contain hypoechoic noncompressible material or a thrombus (Fig. 13). Although MR imaging has been described as a useful tool for the diagnosis of localized thrombosis of the foot veins, US is recommended as the first-line imaging modality [55].

Fig. 13.

Sonogram of plantar vein thrombosis. Short axis sonogram of the plantar foot shows two enlarged thrombosed plantar veins with a small artery in the middle (arrowhead). Note the overlying flexor digitorum brevis muscle (FDB)

Conclusion

Plantar hindfoot pain is a common orthopedic complaint with plantar fasciopathy the most common etiology of heel pain. Sonography can easily reveal the pathologic findings of plantar fasciopathy as well as assess for alternative causes of heel pain.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge and thank Jay Smith, M.D. and the Mayo Clinic Procedural Skills Laboratory for access to the cadaveric specimens and photography of the plantar foot dissections.

Conflict of interest

Douglas F. Hoffman, Heather L. Grothe, Stefano Bianchi declare that they have no conflict of interest related to this paper.

Human and animal studies

The study described in this article does not include any procedures involving humans or animals.

References

- 1.Hill CL, Gill TK, Menz HB, Taylor AW, et al. Prevalence and correlates of foot pain in a population-based study: the North West Adelaide Health Study. J Foot Ankle Res. 2008;1:1. doi: 10.1186/1757-1146-1-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hannan MT, McLennan CE, Rivinus MC, et al. Population-based study of foot disorders in men and women from the Framingham Study (abstract) Arthritis Rheum. 2006;54(suppl):S497. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Thomas MJ, Roddy E, Zhang W, et al. The population prevalence of foot and ankle pain in middle and old age: a systematic review. Pain. 2011;152:2870. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2011.09.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Riddle DL, Schappert SM. Volume of ambulatory care visits and patterns of care for patients diagnosed with plantar fasciitis: a national study of medical doctors. Foot Ankle Int. 2004;25:303. doi: 10.1177/107110070402500505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hoffman D, Bianchi S. Sonographic evaluation of plantar hindfoot and midfoot pain. J Ultrasound Med. 2013;32:1271. doi: 10.7863/ultra.32.7.1271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Stecco C, Corradin M, Macchi V, et al. Plantar fascia anatomy and its relationship with Achilles tendon and paratenon. J Anat. 2013;223(6):665–676. doi: 10.1111/joa.12111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Moraes MR, Cavalcante ML, Leite JA, et al. Histomorphometric evaluation of mechanoreceptors and free nerve endings in human lateral ankle ligaments. Foot Ankle Int. 2008;29(1):87–90. doi: 10.3113/FAI.2008.0087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sarrafian SK, Kelikian AS. Retaining systems and compartments. In: Kelikian AS, editor. Sarrafian’s anatomy of the foot and ankle. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins; 2011. p. p154. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Moraes do Carmo Clarissa Canella, Fonseca de Almeida Melão Lina Isabel, Valle de Lemos Weber Marcio Freitas, Trudell Debra, Resnick Donald. Anatomical features of plantar aponeurosis: cadaveric study using ultrasonography and magnetic resonance imaging. Skeletal Radiology. 2008;37(10):929–935. doi: 10.1007/s00256-008-0497-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bianchi S, Martinoli C Foot (2007) In: Bianchi S, Martinoli C (eds). Ultrasound of the musculoskeletal system. Springer, Berlin, p 835

- 11.Karabay N, Toros T, Hurel C. Ultrasonographic evaluation in plantar fasciitis. J Foot Ankle Surg. 2007;46(6):442–446. doi: 10.1053/j.jfas.2007.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ieong E, Afolayan J, Carne A, et al. Ultrasound scanning for recalcitrant plantar fasciopathy. Basis of a new classification. Skeletal Radiol. 2013;42(3):393–398. doi: 10.1007/s00256-012-1470-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Snider MP, Clancy WG, McBeath AA. Plantar fascia release for chronic plantar fasciitis in runners. Am J Sports Med. 1983;11(4):215–219. doi: 10.1177/036354658301100406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lemont H, Ammirati KM, Usen N. Plantar fasciitis: a degenerative process (fasciosis) without inflammation. J Am Podiatr Med Assoc. 2003;93(3):234–237. doi: 10.7547/87507315-93-3-234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.van Holsbeck M, Introcaso JH. Musculoskeletal ultrasonography. Radiol Clin North Am. 1992;30(5):907–925. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gibbon WW, Long G. Ultrasound of the plantar aponeurosis (fascia) Skeletal Radiol. 1999;28(1):21–26. doi: 10.1007/s002560050467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sabir N, Demirlenk S, Yagci B, et al. Clinical utility of sonography in diagnosing plantar fasciitis. J Ultrasound Med. 2005;24(8):1041–1048. doi: 10.7863/jum.2005.24.8.1041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wall JR, Harkness MA, Crawford A. Ultrasound diagnosis of plantar fasciitis. Foot Ankle. 1993;14(8):465–470. doi: 10.1177/107110079301400807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Walther M, Radke S, Kirschner S, et al. Power Doppler findings in plantar fasciitis. Ultrasound Med Biol. 2004;30(4):435–440. doi: 10.1016/j.ultrasmedbio.2004.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kane D, Greaney T, Bresnihan B, et al. Ultrasound guided injection of recalcitrant plantar fasciitis. Ann Rheum Dis. 1998;57(6):383–384. doi: 10.1136/ard.57.6.383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tsai WC, Wang CL, Tang FT, et al. Treatment of proximal plantar fasciitis with ultrasound-guided steroid injection. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2000;81(10):1416–1421. doi: 10.1053/apmr.2000.9175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tsai WC, Hsu CC, Chen CP, et al. Plantar fasciitis treated with local steroid injection: comparison between sonographic and palpation guidance. J Clin Ultrasound. 2006;34(1):12–16. doi: 10.1002/jcu.20177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hyer CF, Vancourt R, Block A. Evaluation of ultrasound-guided extracorporeal shock wave therapy (ESWT) in the treatment of chronic plantar fasciitis. J Foot Ankle Surg. 2005;44(2):137–143. doi: 10.1053/j.jfas.2005.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Folman Y, Bartal G, Breitgand A, et al. Treatment of recalcitrant plantar fasciitis by sonographically-guided needle fasciotomy. Foot Ankle Surg. 2005;11:211. doi: 10.1016/j.fas.2005.08.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fessell DP, Jacobson JA. Ultrasound of the hindfoot and midfoot. Radiol Clin North Am. 2008;46(6):1027–1043. doi: 10.1016/j.rcl.2008.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Leach R, Jones R, Silva T. Rupture of the plantar fascia in athletes. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1978;60(4):537–539. doi: 10.2106/00004623-197860040-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jl Acevedo, Beskin JL. Complications of plantar fascia rupture associated with corticosteroid injection. Foot Ankle Int. 1998;19(2):91–97. doi: 10.1177/107110079801900207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Louwers MJ, Sabb B, Pangilinan PH. Ultrasound evaluation of a spontaneous plantar fascia rupture. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2010;89(11):941–944. doi: 10.1097/PHM.0b013e3181f711e2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yu JS. Pathologic and post-operative conditions of the plantar fascia: review of MR imaging appearances. Skeletal Radiol. 2000;29(9):491–501. doi: 10.1007/s002560000230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rondhuis JJ, Huson A. The first branch of the lateral plantar nerve and heel pain. Acta Morphol Neerl Scand. 1986;24(4):269–279. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.del Sol M, Olave E, Gabrielli C, et al. Innervation of the abductor digiti minimi muscle of the human foot: anatomical basis of the entrapment of the abductor digiti minimi nerve. Surg Radiol Anat. 2002;24(1):18–22. doi: 10.1007/s00276-002-0001-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kenzora JE. The painful heel syndrome: an entrapment neuropathy. Bull Hosp Jt Dis Orthop Inst. 1987;47(2):178–189. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Baxter DE, Thigpen CM. Heel pain–operative results. Foot Ankle. 1984;5(1):16–25. doi: 10.1177/107110078400500103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Louisia S, Masquelet AC. The medial and inferior calcaneal nerves: an anatomic study. Surg Radilo Anat. 1999;21(3):169–173. doi: 10.1007/BF01630895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Presley JC, Maida E, Pawlina W, et al. Sonographic visualization of the first branch of the lateral plantar nerve (baxter nerve): technique and validation using perineural injections in a cadaveric model. J Ultrasound Med. 2013;32(9):1643–1652. doi: 10.7863/ultra.32.9.1643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Baxter DE, Pfeffer GB, Thigpen M. Chronic heel pain. Treatment rationale. Orthop Clin North Am. 1989;20(4):563–569. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Alshami AM, Souvlis T, Coppieters MW. A review of plantar heel pain of neural origin: differential diagnosis and management. Man Ther. 2008;13(2):103–111. doi: 10.1016/j.math.2007.01.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chundru U, Liebeskind A, Seidelmann F, et al. Plantar fasciitis and calcaneal spur formation are associated with abductor digiti minimi atrophy on MRI of the foot. Skeletal Radiol. 2008;37(6):505–510. doi: 10.1007/s00256-008-0455-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Farooki S, Theodorou DJ, Sokoloff RM, et al. MRI of the medial and lateral plantar nerves. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 2001;25(3):412–416. doi: 10.1097/00004728-200105000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Recht MP, Grooff P, Ilaslan H, et al. Selective atrophy of the abductor digiti quinti: an MRI study. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2007;189(3):W123–W127. doi: 10.2214/AJR.07.2229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Murphey MD, Ruble CM, Tyszko SM, et al. From the archives of the AFIP: musculoskeletal fibromatoses: radiologic-pathologic correlation. Radiographics. 2009;29(7):2143–2173. doi: 10.1148/rg.297095138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wortsman X. Common applications of dermatologic sonography. J Ultrasound Med. 2012;31(1):97–111. doi: 10.7863/jum.2012.31.1.97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.McNally EG, Shetty S. Plantar fascia: imaging diagnosis and guided treatment. Semin Musculoskelet Radiol. 2010;14(3):334–343. doi: 10.1055/s-0030-1254522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Valle M, Zamorani M. Skin and subcutaneous tissue. In: Bianchi S, Martinoli C, editors. Ultrasound of the musculoskeletal system. Berlin: Springer; 2007. p. 19. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Griffith JF, Wong TY, Wong SM, et al. Sonography of plantar fibromatosis. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2002;179(5):1167–1172. doi: 10.2214/ajr.179.5.1791167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Berger FH, de Jonge MC, Maas M. Stress fractures in the lower extremity. The importance of increasing awareness amongst radiologists. Eur J Radiol. 2007;62(1):16–26. doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2007.01.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Garcia-Patos V. Rheumatoid nodule. Semin Cutan Med Surg. 2007;26(2):100–107. doi: 10.1016/j.sder.2007.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Jones RO, Chen JB, Pitcher D, et al. Rheumatoid nodules affecting both heels with surgical debulking: a case report. J Am Podiatr Med Assoc. 1996;86(4):179–182. doi: 10.7547/87507315-86-4-179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sanders TG, Linares R, Su A. Rheumatoid nodule of the foot: MRI appearances mimicking an indeterminate soft tissue mass. Skeletal Radiol. 1998;27(8):457–460. doi: 10.1007/s002560050418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Nalbant S, Corominas H, Hsu B, et al. Ultrasonography for assessment of subcutaneous nodules. J Rheumatol. 2003;30(6):1191–1195. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Jin W, Kim GY, Park SY, et al. The spectrum of vascularized superficial soft-tissue tumors on sonography with a histopathologic correlation: part 2, malignant tumors and their look-alikes. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2009;195(2):446–453. doi: 10.2214/AJR.09.3846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Diniz Mdos S, Almeida LM, Machado-Pinto J, et al. Rheumatoid nodules: evaluation of the therapeutic response to intralesional fluorouracil and triamcinolone. An Bras Dermatol. 2011;86(6):1236–1238. doi: 10.1590/S0365-05962011000600035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sarrafian SK, Kelikian AS. Angiology. In: Kelikian AS, editor. Sarrafian’s anatomy of the foot and ankle. 3. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins; 2011. pp. 302–380. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Siegal DS, Wu JS, Brennan DD, et al. Plantar vein thrombosis: a rare cause of plantar foot pain. Skeletal Radiol. 2008;37(3):267–269. doi: 10.1007/s00256-007-0419-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Bernathova M, Bein E, Bendix N, et al. Sonographic diagnosis of plantar vein thrombosis: report of 3 cases. J Ultrasound Med. 2005;24(1):101–103. doi: 10.7863/jum.2005.24.1.101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]