Abstract

Lal peda is a popular heat desiccated traditional dairy delicacy of eastern India specially Uttar Pradesh. It is prepared by blending of khoa and sugar followed by heat desiccation until characteristic reddish brown colour appears. It is a nutritive, palatable and a very good source of energy. In order to commercially manufacture and market lal peda, studies on its shelf-life were considered to be very important. Lal peda samples were packed in paper boxes and stored at two different temperatures i.e. 4 and 37 °C and physico-chemical and sensory changes were monitored during storage period. There was a continuous loss of moisture during storage and rate of loss of moisture was higher at 37 °C. FFA and HMF contents in lal peda increased during storage and these changes were found to be temperature sensitive. Changes in textural properties of lal peda in terms of hardness, springiness, cohesiveness, chewiness and gumminess were also studied. Lal peda samples stored at 4 and 37 °C were acceptable up to 31 days and 9 days, respectively on the basis of textural and sensory attributes.

Keywords: Lal peda, Thiobarbituric acid, Hydroxy methyl furfural, Free fatty acid, Textural changes, Sensory attributes

Introduction

India is the largest milk producing country in the world. According to US Department of Agriculture, India’s milk production in 2010 was 117 million tons (Bhasin 2010; Anon 2011). Conversion of liquid milk into traditional dairy products increases the longevity of milk solids. The consumption of sweets is an integral part of Indian dietary system. Traditional dairy products have great commercial significance as they account for over 90% of all dairy products consumed in the country (Aneja et al. 2002). About 50–55% of milk produced is converted into a variety of Indian milk products by the traditional sector (by halwais or sweetmeat makers) using processes such as heat desiccation, heat acid coagulation and fermentation, out of which about, 5.5% of total milk production is utilized for khoa making in India (Banerjee 1997; Bandyopadhyay et al. 2006). Cow milk usually yields 17–19% of khoa by weight. The yield of khoa from buffalo milk is reported to be 21–23% by weight (De 1980). The quality of khoa produced from buffalo milk is superior to khoa produced from cow milk. Emulsifying capacity of buffalo milk fat is higher due to the presence of larger proportion of butyric acid-containing trigycerides and release of more free fat compared to cow milk which may be responsible for smooth and mellow texture of khoa (Sindhu 1996).

Burfi and peda are the two major khoa based sweets, which are highly popular among Indians mainly because of their delicious taste and high nutritional value. It has been reported that the quantity of peda produced in India far exceeds any other indigenous milk based sweet (Mahadevan 1991). Several types of peda are marketed in different regions of the country with modifications in the process i.e. Doodh peda/Mathura peda (Uttar Pradesh), Kunthalgiri peda (Karnataka), Dharwad peda (Karnataka), Lal peda (Eastern Uttar Pradesh), Plain peda, Kesar peda, Brown peda, etc. Kunda, Thabdi, Bal mithai and Kalakand are similar heat desiccated traditional dairy products characterized by a semi brown to brown color, soft body and grainy texture. Earlier, the work has been done on brown peda samples collected from different parts of the country and they were evaluated on the basis of their sensory, chemical, rheological, microbiological and colour attributes (Londhe and Pal 2008). Khoa and khoa based sweets, including peda, have a poor shelf life due to loss of moisture, development of rancidity and surface mould growth upon storage (Londhe and Pal 2007).

Lal peda is a popular heat desiccated indigenous dairy sweet especially in Varanasi, Uttar Pradesh, due to its cooked taste and comparatively longer shelf-life. Lal peda is produced on small scale by local sweetmeat makers. It is generally prepared from khoa (prepared from cow milk, buffalo milk or a combination of both) as a base material and sugar. Lal peda is characterised by its reddish brown colour due to caramelization of sucrose during heat processing. Pandey et al. (2007) prepared lal peda and the highest yield was reported for the product prepared from mixed milk with 60% sugar. The standardized lal peda was prepared in our laboratory for characterizing the traditional dairy products of India and generating valuable database on the physico-chemical, textural and sensory changes of lal peda during storage at two different temperatures i.e. 4 and 37 °C.

Materials and methods

The work was carried out in the laboratory of Centre of Food Science and Technology, Banaras Hindu University, Varanasi, India. Milk (Standardized mixed milk; 6% fat and 9% SNF) and sugar used for manufacturing of lal peda and paper board boxes for packaging were procured from the local market of Varanasi, India.

Manufacture of lal peda

Lal peda was manufactured by using standardized milk (6% fat and 9% SNF) procured from local market of Varanasi, India. Milk was concentrated with continuous stirring up to 67% TS for making khoa. Khoa was cooled to 25 ± 3 °C for 15 min. Khoa and sugar (35% of khoa) were taken in a vessel and heated for desiccation with continuous stirring till the product attained a reddish brown colour. Lal peda was cooled to 25 ± 3 °C and was cut into pieces by using sharp edged knife. Samples were then packed in paper board boxes.

Proximate analysis

Moisture, ash, fat, protein, sucrose and lactose were analyzed in lal peda samples by following the AOAC (2000) methods.

Storage and analysis of lal peda

The samples of lal peda were stored in paper board boxes at two temperatures i.e. 4 and 37 °C. The samples were analyzed at 4 days interval of storage for sensory, physico-chemical and textural changes.

Changes in sensory attributes

The sensory attributes of lal peda were analyzed for colour, flavour, texture, sweetness and overall acceptability by a semi-trained panel of judges consisting of seven members by using a nine point hedonic scale (1 = dislike extremely; 9 = like extremely).

Free fatty acid (FFA)

The method prescribed by Deeth et al. (1975) was used to estimate the FFA content of lal peda.

Hydroxy methyl furfural (HMF)

The HMF content in lal peda was determined by following the method of Keeney and Bassette (1959) with slight modifications. Lal peda (0.5 g) sample was thoroughly mixed with 9.5 ml distilled water. Five ml of 3 N oxalic acid was added and the tubes were kept in boiling water bath for 60 min. The contents of the tubes were cooled and 5 ml of 40% trichloroacetic acid solution was added. The precipitated mixture was filtered through Whatman No. 42 filter paper. Filtrate (0.5 ml) was pipetted out into a 5 ml test tube and added with 3.5 ml of distilled water and 1 ml of 0.05 M thiobarbituric acid solution (aq.) and was mixed well. Tubes were kept in water bath at 40 °C for 50 min. After cooling to room temperature, absorbance was measured at 443 nm. A blank was run in the same manner as those for the samples, substituting distilled water for lal peda. A standard curve of HMF concentration and optical density at 443 nm was drawn by using a range of 1.0 to 10 μmol/ml (0.5 ml aliquot) HMF concentrations.

Thiobarbituric acid (TBA) value

The extent of oxidation of fat in lal peda was measured in terms of TBA value. The extraction method of Strange et al. (1977) was adopted with slight modifications. Two gram sample was taken and blended with 50 ml of 20% TCA (trichloroacetic acid) and 50 ml of distilled water. The contents were left undisturbed for 10 min followed by filtration. Five millilitre filtrate was pipetted out in each test tube and added with 5 ml of 0.01 M 2-thiobarbituric acid. The test tubes were heated in boiled water bath for 30 min at 100 °C for colour development. The contents were cooled to 30 °C temperature and absorbance was determined at 532 nm. Blank determinations were made using distilled water in place of sample. TBA value was expressed as absorbance at 532 nm.

Texture profile analysis (TPA)

TPA on lal peda samples was performed on the Texture Analyser (TA.XT plus), Exponent Lite (Stable Micro Systems, UK). TPA was done to characterize the hardness, adhesiveness, springiness, cohesiveness, gumminess, and chewiness of the product. The sample of lal peda was cut into 1 cm3 size pieces and temperature of the sample was maintained at 25 °C during texture analysis. The samples were subjected to monoaxial compression of 5 mm height. The force distance curve was obtained for a two bite compression cycle with the test speed of 1 mm/s and trigger force of 5 g.

Statistical analysis

All the data were expressed as mean ± standard error of mean was calculated from three independent experiments. One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was applied by using the Systat software to measure the test for significance as described by Snedecor and Cochran (1989).

Results and discussion

Proximate composition of lal peda

The proximate composition of lal peda was analyzed and consisted of 12.4% moisture, 16.7% lactose, 17.2% protein, 18.5% fat, 3% ash and 32.2% sucrose. Londhe and Pal (2008) reported moisture content in peda ranged from 12.01 (Dharwad peda) to 13.04% (Mathura peda), which is in close range with the current findings. Compositional differences between cow and buffalo milk lead to qualitative and quantitative characteristics in the product. As buffalo milk has higher solids than cow and mixed milk, variation in product quality is obvious. Cow milk products have a characteristic to retain higher moisture content. Lal peda requires higher temperature and longer duration of heating to achieve the brown coloration and higher release of free fat. The higher amount of free fat is a typical characteristic in lal peda because consumer perception about this sweet goes in favour of high free fat and intense brown colour.

Chemical changes in lal peda during storage

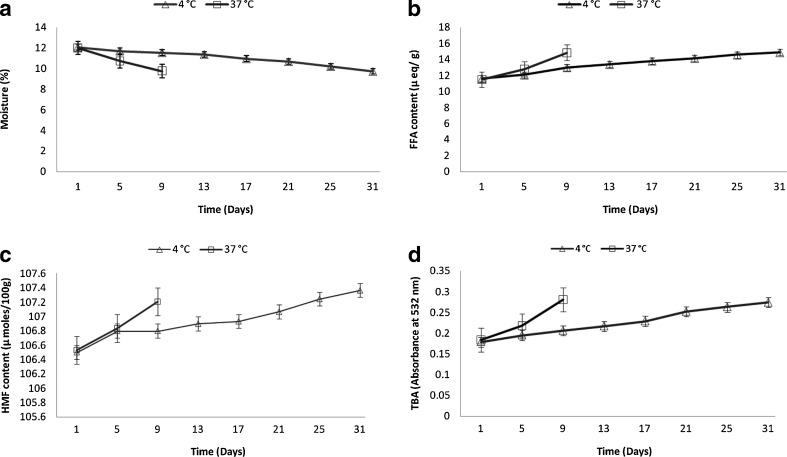

Chemical changes (moisture loss, FFA, HMF and TBA content) in lal peda during storage at two different temperatures (4 and 37 °C) are shown in Fig. 1. The rate of loss of moisture content in samples was higher at 37 °C as compared with those stored at 4 °C (Fig. 1a). The moisture content of lal peda at each interval of storage varied significantly (p < 0.01). Moisture content of lal peda stored at 4 °C decreased from 12.07 to 9.73% in 31 days as compared to decrease in moisture from 12.0 to 9.75% in lal peda stored at 37 °C up to 9 days.

Fig. 1.

Physicochemical changes in lal peda during storage at two different temperatures (n = 3). a Moisture Content (%) b Free fatty acid (FFA) (μeq/g) c Hydroxy methyl furfural (HMF) (μmoles/100 g) d Thiobarbituric acid (TBA) (Absorbance at 532 nm)

The lal peda samples were analysed for free fatty acid content with a view to monitor the lipolytic changes during storage. The changes in FFA content of lal peda during storage are shown in Fig. 1b. The FFA content of lal peda increased significantly (p < 0.01) with the progression of storage period. A gradual increase of fatty acids in lal peda samples was noticed during storage. The rate of increase in FFA was maximum in lal peda stored at 37 °C, wherein free fatty acids increased from initial value of 11.49 on first day to 14.84 μeq/g after storage period of 9 days. The rate of increase in free fatty acids was slower in lal peda stored at 4 °C as compared to lal peda sample stored at 37 °C (Fig. 1b). The release of free fat during the preparation of lal peda and presence of high moisture content could be responsible for lipolysis during storage, the rate of which is expected to be higher at higher temperature of storage. Yadav and Beniwal (2009) also found significant increase in free fatty acids with storage time in peda even after addition of antioxidant and preservative, stored at −15 ± 2 °C (subzero temperature). The FFA content of lal peda was in the range of 11.63–14.87 μeq/g during storage at 4 °C for 31 days. Jha et al. (1977) and Kumar et al. (2010) also reported that free fatty acids in khoa increased significantly with the progression of storage period.

HMF is the index of browning in dairy products. The values for HMF (μmoles/100 g) content during storage of lal peda are shown in Fig. 1c. HMF content of lal peda increased gradually with the storage period at 4 and 37 °C. The presence of oxygen converts -SH groups to S-S group leading to increase in browning and HMF value (Jenness and Patton 1959). There was no significant difference in HMF content with the progress of storage (p < 0.01). Maillard reaction products have been shown to have antioxidant activity in some fat containing foods (Kirigaya et al. 1968). The HMF content increased from 106.5 to 107.36 μmoles/100 g in lal peda both stored at 4 and 37 °C.

The extent of oxidation of fat in lal peda was measured in terms of its TBA value. TBA was expressed as absorbance at 532 nm. Effect of storage on TBA values (absorbance at 532 nm) of lal peda is depicted in Fig. 1d. It showed the significant difference (p < 0.01) of storage on TBA values. TBA values in lal peda stored at 37 °C, increased consistently, with the increase in storage period as compared to lal peda stored at 4 °C. Kumar et al. (2010) also reported significant increase in TBA values with time in stored khoa samples, containing antioxidants. On initial day of storage, the TBA content of lal peda samples stored at 4 °C and 37 °C were 0.179 and 0.184, which increased to 0.274 and 0.281 during storage after 31 days and 9 days, respectively. Autoxidation is known to proceed at a faster rate in the samples stored at higher temperatures. A significant increase in TBA values observed with storage time may be because of oxidation of fat in lal peda samples. Free fat present in lal peda is also vulnerable to oxidation.

Changes in textural properties

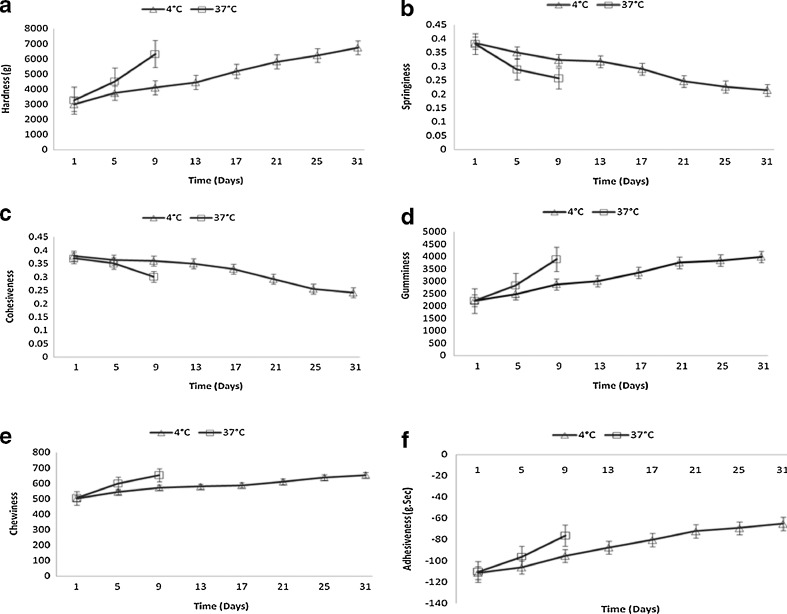

Texture is an important attribute in peda which also decides the ultimate acceptance of the product by consumers. The changes in the textural attributes (hardness, springiness, cohesiveness, chewiness, gumminess and adhesiveness) of lal peda during storage are presented in Fig. 2. Deteriorative textural changes were rapid at 37 °C in comparison to 4 °C, during the storage period. The hardness values were significantly higher (p < 0.01) in lal peda throughout the storage period (Fig. 2a). This could be attributed to the continuous reduction in moisture content and consequent increase in total solids mainly contributed by sucrose. This is in accordance with the findings of Gupta et al. (1990) and Suresh and Jha (1994) who have reported that the increased hardness of khoa correlated with the increase in total solids, and by increasing the total solids in khoa, hardness also increased. Patel et al. (1990) also reported that the moisture content of peda had direct relationship with hardness. It was observed that springiness values of lal peda reduced consistently (p < 0.01) with the increase in storage period (Fig. 2b). Springiness values of lal peda during storage at 4 and 37 °C ranged in between 0.384–0.214 and 0.381–0.257, respectively. It could be because of the porous texture of lal peda made with sucrose.

Fig. 2.

Changes in instrumental textural attributes of lal peda during storage at two different temperatures (n = 3). a Hardness (g) b Springiness c Cohesiveness d Gumminess e Chewiness f Adhesiveness (g.sec)

Cohesiveness is the ratio of area under the second bite curve before reversal compression to that under the first bite curve. Cohesiveness of the product also reduced consistently throughout the storage period (Fig. 2c). It may be attributed with the loss of moisture content and increasing total solids. Gupta et al. (1990) reported that cohesiveness of khoa tended to decline with increasing total solids. Cohesiveness of lal peda ranged between 0.38–0.24 and 0.37–0.30 during storage at 4 and 37 °C for 31 and 9 days, respectively. Gumminess is related to primary parameters of hardness and cohesiveness and is obtained by multiplication of these two parameters. Chewiness refers to the energy required to masticate food into a state ready for swallowing and is a product of gumminess and springiness. A significant increase in gumminess and chewiness (p < 0.01) were observed in lal peda upon storage (Fig. 2d and e). More variation in gumminess was seen at 37 °C storage temperature of lal peda compared to the 4 °C storage temperature of lal peda. Chewiness followed the same trend as gumminess.

Adhesiveness is related to the sensory stickiness. Adhesiveness reduced consistently (p < 0.01) with the progress of storage period (Fig. 2f). Adhesiveness ranged between 111.45–65.27 and 107.53–76.24 g.sec of lal peda during storage at 4 and 37 °C of 31 and 9 days, respectively. The decrease in adhesion in lal peda could be because of the decrease in free moisture during storage. Higher adhesiveness values can be attributed to higher moisture content in peda (Londhe and Pal 2008).

Changes in sensory attributes of lal peda during storage

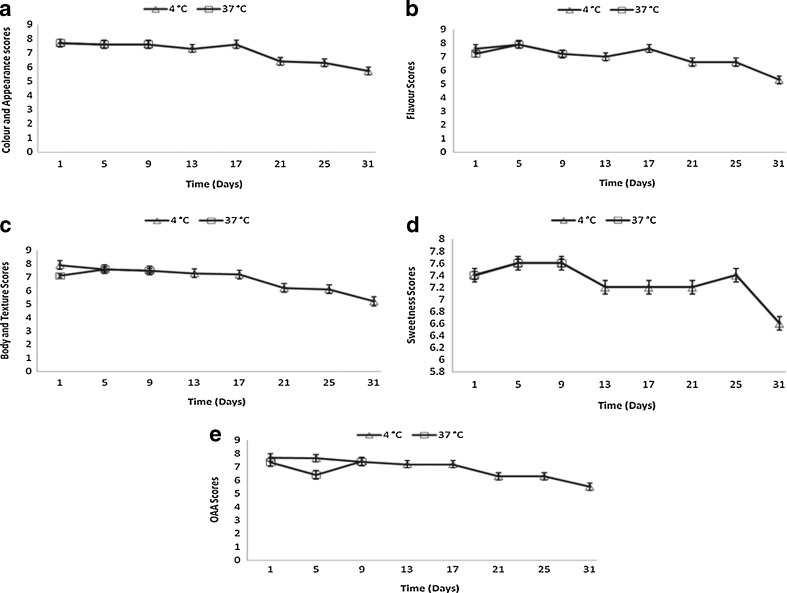

The results of the sensory evaluation of lal peda during storage at two different temperatures i.e. 4 and 37 °C are given in Fig. 3. The sensory scores decreased rapidly because of the continuous loss of moisture and resultant textural characteristics and oxidation of fat with the progression of storage period. In a similar study on brown peda, changes in sensory scores were largely attributed to the differences in the method of preparation and chemical composition, particularly fat and sugar levels in the final product (Londhe and Pal 2008).

Fig. 3.

Changes in sensory quality of lal peda during storage at two different temperatures (n = 7). a Colour and appearance scores b Flavour scores c Body and texture scores d Sweetness scores e Overall acceptability (OAA) scores

The lal peda samples showed significant (p < 0.01) decrease in colour and appearance scores at 4 and 37 °C during storage (Fig. 3a). The score ranged between 7.7–5.7 and 7.7–4.4 during storage at 4 and 37 °C, respectively. Flavour scores of lal peda, decreased continuously during the storage period and ranged from 7.6 at first day to 5.3 on 31st day at 4 °C (Fig. 3b). Body and texture score of lal peda stored at 4 °C was found to be acceptable up to 31 days as compared with 9 days for lal peda stored at 37 °C (Fig. 3c). In terms of sweetness perception, there were no significant differences throughout the storage period at 37 °C for 9 days and at 4 °C till 25th day, but on 31st day the score was significantly lower i.e. 6.6 (Fig. 3d). There was a significant (p < 0.01) effect of storage temperature on the overall acceptability scores (Fig. 3e). The overall acceptability scores of lal peda, decreased with progressive period of storage at both the temperatures.

Conclusions

Lal peda is an indigenous dairy product of India. Its acceptance by consumers depends on its quality and shelf life. Therefore, a study was planned to systematically characterize and delineate the sensory, physico-chemical and textural changes of lal peda during storage. This study showed that temperature of storage significantly affects the sensory, physico-chemical and textural attributes of lal peda. Lal peda samples stored at 4 °C were sensorily acceptable upto 31 days. However, samples stored at 37 °C, could not be stored for more than 9 days in view of fast deteriorative changes in terms of sensory, physico-chemical and textural attributes. This study is useful from the point of view of the need to undertake concerted efforts in characterizing and enhancing the shelf-life of traditional dairy products of India. This also provides sufficient leads to undertake newer studies pertaining to enhancing the shelf life of not only lal peda but also other indigenous dairy products of India.

References

- Methods of analysis. 17. USA: Association of Official Analytical Chemists Washington; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Aneja RP, Mathur BN, Chauhan RC, Banerjee AK (2002) Technology of Indian dairy products. pp 122–125

- Anon (2011) Milk output in India to touch record 121.5 million tonnes in 2011. http://www.livemint.com/2011/01/11161514/Milk-output-in-India-to-touch.html. 12/08/2011

- Bandyopadhyay M, Mukherjee RS, Chakraborty R, Raychaudhuri U. A survey on formulations and process techniques of some special Indian traditional sweets and herbal sweets. Indian Dairyman. 2006;58:23–35. [Google Scholar]

- Banerjee AK (1997) Processes for commercial production. Dairy India 5th edn. Published by PR Gupta, New Delhi, India, pp 387

- Bhasin NR. President’s desk. Indian Dairyman. 2010;62:12–13. [Google Scholar]

- De S. Outlines of dairy technology. New Delhi: Oxford University Press; 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Deeth HC, Fitz-Gerald CH, Wood AF. A convenient method for determining the extent of lipolysis in milk. Aust J Dairy Tech. 1975;30:109–111. [Google Scholar]

- Gupta SK, Patil GR, Patel AA, Garg FC, Rajorhia GS. Instron texture profile parameters of khoa as influenced by composition. J Food Sci Tech. 1990;27:209–213. [Google Scholar]

- Jenness R, Patton S. Principles of dairy chemistry. New York: Wiley; 1959. [Google Scholar]

- Jha YK, Singh S, Singh S. Effect of antioxidants and antimicrobial substances on keeping quality of khoa. Indian J Dairy Sci. 1977;30:1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Keeney M, Bassette R. Detection of intermediate compounds in early stages of browning reaction in milk products. J Dairy Sci. 1959;42:945–960. doi: 10.3168/jds.S0022-0302(59)90678-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kirigaya N, Kato H, Fujimaki M. Studies on antioxidants activity of nonenzymic browning reaction products:1 relations of colour intensity and reductones with antioxidant activity of browning reaction products. Agric Biol Chem. 1968;32:287–290. doi: 10.1271/bbb1961.32.287. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar M, Beniwal BS, Rai DC. Effect of antioxidant on shelf life of khoa under refrigerated conditions. Egypt J Dairy Sci. 2010;38:211–218. [Google Scholar]

- Londhe G, Pal D. Developments in shelf life extension of khoa and khoa based sweets-an overview. Indian J Dairy Biosci. 2007;18:1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Londhe GK, Pal D. Studies on the quality evaluation of market samples of brown peda. Indian J Dairy Sci. 2008;61:347–352. [Google Scholar]

- Mahadevan AL (1991) Nutritive value of traditional milk products. Proceedings of Workshop on Indigenous Milk Products held at National Dairy Development Board, Anand. January 15–19, pp 62

- Pandey RK, Patel PR, Govindam, Chaubey CS (2007) Lal peda preparation and its yield estimation. Bioved Survey of Indian Agriculture, pp 239–242

- Patel AA, Patil GR, Garg FC, Rajorhia GS (1990) Texture of peda as measured by instron. Proceedings of XXIII Int. Dairy Cong., Montreal, Canada. Brief Communication

- Sindhu JS. Suitability of buffalo milk for products manufacturing. Indian Dairyman. 1996;48:41–47. [Google Scholar]

- Snedecor GW, Cochran WG. Statistical methods. 8. Ames: Iowa State University Press, USA; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Strange ED, Benedict RC, Smith JL, Swift CE. Evaluation of rapid tests for monitoring alterations in meat quality during storage. J Food Protect. 1977;10:843–847. doi: 10.4315/0362-028X-40.12.843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suresh I, Jha YK. Sensory, biochemical and microbiological qualities of kalakand. J Food Sci Tech. 1994;31:330–332. [Google Scholar]

- Yadav R, Beniwal BS. Effect of antioxidants and preservatives on keeping quality of peda stored at sub-zero temperature. J Dairy Foods Home Sci. 2009;28:164–169. [Google Scholar]