Abstract

Previously we observed that capsaicin, a transient receptor potential vanilloid 1 (TRPV1) receptor activator, inhibited transient potassium current (IA) in capsaicin-sensitive and capsaicin-insensitive trigeminal ganglion (TG) neurons from rats. It suggested that the inhibitory effects of capsaicin on IA have two different mechanisms: TRPV1-dependent and TRPV1-independent pathways. The main purpose of this study is to further investigate the TRPV1-independent effects of capsaicin on voltage-gated potassium channels (VGPCs). Whole cell patch-clamp technique was used to record IA and sustained potassium current (IK) in cultured TG neurons from trpv1 knockout (TRPV1−/−) mice. We found that capsaicin reversibly inhibited IA and IK in a dose-dependent manner. Capsaicin (30 μM) did not alter the activation curve of IA and IK but shifted the inactivation–voltage curve to hyperpolarizing direction, thereby increasing the number of inactivated VGPCs at the resting potential. Administrations of high concentrations capsaicin, no use-dependent block, and delay of recovery time course were found on IK and IA. Moreover, forskolin, an adenylate cyclase agonist, selectively decreased the inhibitory effects of IK by capsaicin, whereas none influenced the inhibitions of IA. These results suggest that capsaicin inhibits the VGPCs through TRPV1-independent and PKA-dependent mechanisms, which may contribute to the capsaicin-induced nociception.

Keywords: Capsaicin, Voltage-gated potassium channels, Trigeminal ganglion, TRPV1

Introduction

Voltage-gated potassium channels (VGPCs) are important physiological regulators of membrane potentials. They are widely expressed in excitable tissues including sensory ganglia. Patch-clamp studies in trigeminal ganglion (TG) neurons have identified two types of potassium currents, a transient current (IA) and a sustained current (IK) (Liu and Simon 2003). Recently, VGPCs have been received extensive attention as drug targets for the treatment of a variety of pain, such as neuropathic pain and inflammatory pain (Brederson et al. 2013; Takeda et al. 2006; Xu et al. 2006; Sculptoreanu et al. 2004; Malykhina et al. 2013; Hakim et al. 2009; Stewart et al. 2003; Nie et al. 2009), due to their essential role in stabilizing the resting membrane potential and controlling the frequency of nociceptor firing (Maljevic and Lerche 2013).

Capsaicin, a major pungent constituent of red pepper, is used in various medicinal treatments to alleviate pain, but its initial application causes pain and inflammation by activating and sensitizing nociceptors (Calixto et al. 2005; Palazzo et al. 2012; Premkumar and Abooj 2013; Fischer et al. 2013). It is generally accepted that the initial painful sensation after capsaicin application arises from the selective activation of TRPV1 (transient receptor-potential ion channel of vanilloid subtype-1), which is mainly expressed in sensory neurons. It is reported that the inhibition of IA by inflammatory mediators increases the excitability of nociceptor and leads to pain and hyperalgesia (Liu et al. 2001; Jeub et al. 2011). To determine whether the VGPCs might contribute to the pain induced by capsaicin, we investigated how capsaicin modulated IA in rat TG neurons previously. We found that low concentration of Capsaicin blocked Ia mainly in the capsaicin-sensitive (CS) neurons, while at high concentration (>10 μM), the block of capsaicin on IA exists in both CS and capsaicin-insensitive (CIS) neurons. The results show that there are two mechanisms, TRPV1-dependent and TRPV1-independent effects that may involve in the modulation of capsaicin on IA. Moreover, mounting evidence also suggests that capsaicin exerts its effects through TRPV1 at sub-micromolar concentrations. However, capsaicin at micro- to millimolar concentrations seems to have effects beyond TRPV1-dependent actions (Lundbæk et al. 2005; Boudaka et al. 2007; Hibino et al. 2011; Cao et al. 2007). In accordance with this, it has been shown the inhibitory effects of capsaicin on IA, even at 30 μM, were small relative to CS neurons at 1 μM capsaicin in CIS neurons; this further indicated that the inhibition of TRPV1 independent pathway occurred at concentrations much larger than the inhibition of TRPV1 dependent (Liu and Simon 2003). In TRPV1 positive nociceptors, the initial painful sensation after capsaicin application arouses from the inhibition of IA via TRPV1. However, little has been documented regarding the effects of the capsaicin and its analogs producing pain in TRPV1 negative nociceptors. Thus, the aim of this study is to further explore the TRPV1-independent effects of capsaicin on VGPCs in the primary sensory neurons by using trpv1 knock-out mice (TRPV1−/−). Our findings have implications for understanding a TRPV1-independent mechanism for initial hyperalgesia effects of capsaicin in animals and human beings when TRPV1 is absent.

Materials and Methods

Cell Culture

TG neurons from C57BL6 wild type and TRPV1 knock-out mice (Caterina et al. 2000), the generous gift from Dr David Julius, were cultured using the similar method for adult rats (Liu and Simon 2003). TG were dissected aseptically and collected in Hank’s Balanced Salt Solution (HBSS). After washing three times with HBSS, the ganglia were diced into small pieces and incubated for 30–50 min at 37 °C in 0.1 % collagens (Type XI-s, Sigma) in HBSS. Individual cells were dissociated by triturating the tissue through a fire-polished glass pipette, followed by 10 min incubation at 37 °C in 10 μg/ml DNase I in F-12 medium (Life Technologies, Gaithersburg, MD). After washing three times with F-12 medium, the cells were cultured in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10 % fetal bovine serum. The cells were plated on poly-d-lysine coated glass coverslips (15 mm diameter) and cultured for 12–24 h at 37 °C in a water saturated atmosphere with 5 % CO2. At the beginning of each experiment, neurons were placed for 10 min in a chamber containing the external solution for measuring IA or IK.

Care of animals conformed to standards established by the National Institutes of Health. All efforts were made to minimize animal suffering, and to reduce the number of animals used. All animal protocols were approved by the Duke University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Patch-Clamp Recording

In this experiment, we used glass pipettes (R-6 borosilicate, Drummond Scientific Company, Broomall, PA.) with resistances 1.5 MΩ according to our previous study (Xiong et al. 2013). The pipette solution contained (in mM) 116 KF, 20 KCl, 1.0 CaCl2, 2.0 MgCl2, 10 EGTA, 10 HEPES, and 5 Tris-ATP adjusted to pH 7.3 for both IA and IK. Neurons having projected soma diameters ranging between 18 and 25 μm were used.

The signals were measured using an Axopatch-1D patch-clamp amplifier (Axon instruments, Foster City, CA) and the amplifier output was digitized with a Digidata 1322A converter (Axon instruments). The sampling rate was 10 kHz. The capacitance and series resistance were compensated, the latter by about 90 %. The leak current was subtracted from the potassium currents using Clampfit programs. All experiments were carried out at room temperature (22–25 °C).

IA was obtained from the total outward current using tetraethyl ammonium chloride (TEA-Cl) to block IK; IK was obtained from the total outward current using 4-aminopyridine (4-AP) to block IA (Liu et al. 2004). The voltage-dependent activation curve (G–V curve) was measured by a series of depolarizing pulses (500 ms) from −80 to +40 mV stepping by 10 mV with interval time of 2 s. The voltage-dependent inactivation curve (inactivation–voltage curve) was measured by double pulses: precondition pulses (400 ms) ranging from −100 to +40 mV by stepping 10 mV and following +40 mV test pulse (400 ms) with internal of 4 s. Use-dependent protocol was composed of 16 continually depolarizing pulses (+40 mV) with duration of 500 ms at different frequencies from 0.5 to 1.7 Hz. The recovery time was measured by double pulses, first condition pulse of +40 mV (500 ms) caused the current completed inactivation, as the interval time was increased (from 0.002 to 2 s), and the current evoked by +40 mV test pulse (500 ms) recovered gradually. For all experiments, the holding potential was −80 mV.

Drugs and Solution

Cell culture materials were purchased from GIBCO (Life Technologies, Rockville, MD). Capsaicin and capsazepine were obtained from RBI (Natick, MA), unless otherwise stated; all other chemicals were purchased from Sigma (St. Louis, MO). Capsaicin was prepared as stock solutions in DMSO. The final concentration of DMSO in external solution was ≤0.5 %. No detectable effect of the vehicles was found in our experiments. The recording chamber had a volume of 360 μl and was perfused with the external solution at a rate of 3 ml/min. External solution for IA contented (in mM): choline-Cl, 80; KCl, 5.0; CaCl2, 2.0; MgCl2, 1.0; HEPES, 10; d-glucose, 10; TEA-Cl, 80; CdCl2, 1; for IK contented: choline-Cl, 137; KCl, 5.0; CaCl2, 2.0; MgCl2, 1.0; HEPES, 10; d-glucose, 10; 4-AP, 3.0; CdCl2, 1.

Data Analysis

Data were analyzed and fitted using Clampfit (Axon instruments, Foster City, CA) and Sigmaplot (SPSS inc., Chicago IL) software. Dose–response curve was fitted by a modified Hill equation, which with K1/2 as the concentration producing 50 % effect, n as the cooperative index and where the constants . G-V curve and inactivation curves (h-infinity curve) were fitted by Boltzmann functions, which where V0.5 is the membrane potential (Vm) at which 50 % of activation or inactivation was observed, k is the slope of the function, and a is a constant (a = 0 in the G-V relation). Both the use-dependent curve and the recovery time were fitted by single exponential function: where rate constancy b was represented by TAU. IA and IK were measured at the peak outward current (IP). All of data were presented as mean ± SEM, and the significance was indicated as P < 0.05 and P < 0.01 tested by paired or unpaired Student’s t tests.

Results

Blockage of Capsaicin on VGPCs in the TRPV1+/+ Mice

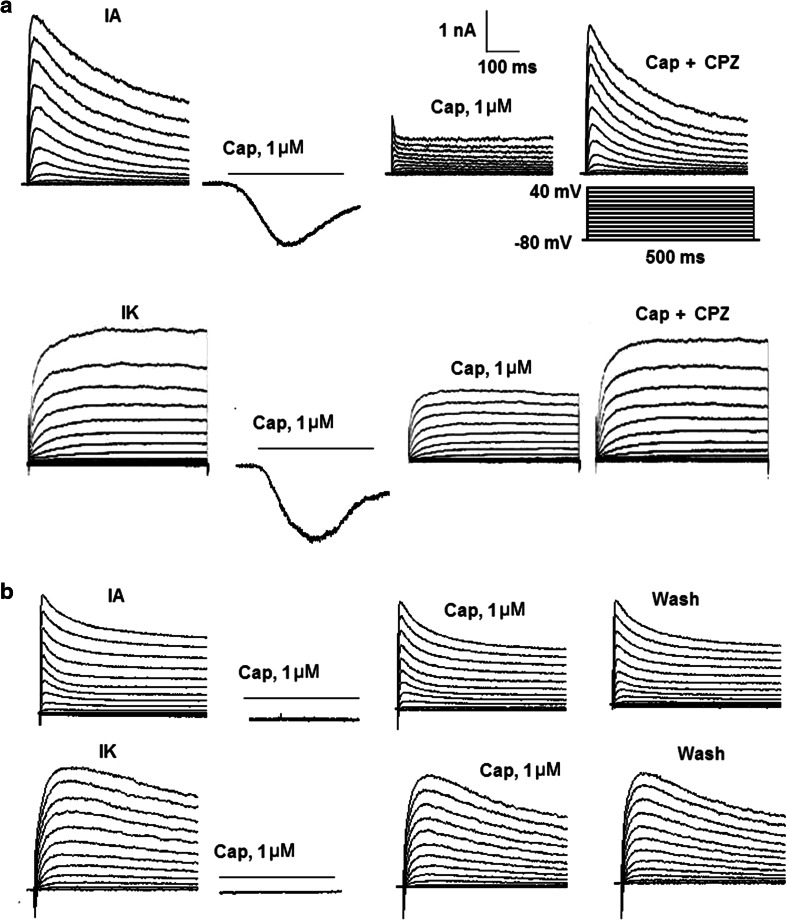

As shown in our previous experiment, in cultured rat TG neurons, capsaicin had different effects on IA in CS and CIS neurons. IA was reduced about 49 % in CS neuron by applying 1 μM capsaicin for 3 min, while only 9 % were inhibited in CIS neurons (Liu and Simon 2003). Similar results were found in the present experiments using TRPV1+/+ mice. After exposure to 1 μM capsaicin for 3 min, IA and IK were reduced by 52.3 ± 17.2 % (n = 7) and 43.4 ± 16.9 % (n = 6) in CS neurons, respectively, while only decreased by 7.2 ± 1.3 % (n = 6) and 8.2 ± 1.5 % (n = 8) in CIS neurons, respectively. The inhibitory effects of 1 μM capsaicin on IA and IK were reversed by capsazepine (a TRPV1 receptor antagonist) in CS neurons. A classical case is shown in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Effects of capsaicin (Cap) on VGPCs in TG neurons from TRPV1+/+ mice. a The application of 1 μM Cap induced an inward current in CS neuron. The typical recordings show that, exposed to 1 μM Cap, IA was reduced from 3.8 to 1.4 nA and IK was decreased from 3.3 to 1.8 nA, respectively. Pre-incubation for 3 min with the TRPV1 antagonist, CPZ (10 μM), inhibited Cap-induced IA and IK decreases. b 1 μM Cap almost had no effects on IA and IK in CIS neuron. The peak amplitude of IA was 2.91, 2.81, and 2.88 nA before, during and after capsaicin application, respectively. The amplitude of IK was 3.06, 2.94, and 2.90 nA before, during, and after Cap application, respectively

Capsaicin Reduced IA and IK in TRPV1−/− Mice

Since the TRPV1-dependent inhibitory effects of capsaicin on IA in CS neurons had been examined in our previous study (Liu and Simon 2003), here we focused on studying the TRPV1-independent effects of capsaicin on VGPCs using TG neurons from TRPV1−/− mice. In TRPV1−/− mice, the effects of capsaicin on IA were dose dependent and reversible, as shown in Fig. 2a, in the presence of 1, 10, 30, and 100 μM capsaicin, IA was reduced by 2.7 ± 6.6 % (n = 6), 29.7 ± 11.9 % (n = 13), 57.5 ± 14.5 % (n = 7), and 81.6 ± 8.8 % (n = 7), respectively. The dose–response curve was fitted to modified Hill equation with K1/2 value of 21 μM. 30 μM capsaicin had no markedly effects on the G-V curve of IA (control: V0.5 = −3.1 ± 2.2 mV, k = 18.0 ± 0.6, n = 11; capsaicin: V0.5 = −3.9 ± 1.8 mV, k = 19.8 ± 0.7, n = 12, P > 0.05) (Fig. 2b), while significantly shifted the inactivation curve to hyperpolarizing potential (Control: V0.5 = −41.6 ± 3.2 mV, k = −7.3 ± 0.8, n = 10; capsaicin: V0.5 = −58.8 ± 3.1 mV, k = −8.2 ± 0.9, n = 9; for V0.5, P < 0.05) (Fig. 2c).

Fig. 2.

Effects of capsaicin on IA in TG neuron from TRPV1−/− mice. a The typical recordings show that IA was reduced from 4.0 nA to 3.5, 2.7, 1.1, and 0.8 nA in the presence of 1, 10, 30, and 100 μM Cap, respectively. The inhibition was reversible after a 3 min wash. The plot showed the percentage of inhibition of IA after application of capsaicin (1–100 μM). b Application of 30 μM Cap had no effect on G–V curve of IA. c The typical recordings show that the amplitude of IA was reduced in the presence of Cap and inactivation–voltage curve shifted to the hyperpolarizing direction

The response of IK to capsaicin is presented in Fig. 3. The effects of capsaicin on IK also were dose dependent and reversible. In the presence of 1, 10, 30, and 100 μM capsaicin, the amplitude of IK was reduced by 9.4 ± 4.8 % (n = 5), 33.1 ± 7.6 % (n = 9), 55.1 ± 6.4 % (n = 8), and 80.5 ± 7.2 % (n = 8), respectively, with K1/2 value of 23 μM. 30 μM capsaicin did not significantly alter the G-V parameters of IK (Control: V0.5 = −5.2 ± 2.7 mV, k = 17.3 ± 0.8, n = 9; capsaicin: V0.5 = −5.8 ± 3.1 mV, k = 17.0 ± 0.9, n = 8; for V0.5, P > 0.05), but shifted the inactivation curve to hyperpolarizing direction (Control: V0.5 = −72.99 ± 1.48 mV, k = −9.6 ± 1.28, n = 9; capsaicin: V0.5 = −83.00 ± 1.22 mV, k = −15.19 ± 1.22, n = 12; for V0.5, P < 0.05).

Fig. 3.

Effects of capsaicin on IK in TG neurons from TRPV1−/− mice. a The typical recordings show that IK was reduced from 5.1 nA to 4.7, 2.7, 1.1, and 0.6 nA in the presence of 1, 10, 30, and 100 μM capsaicin, respectively. After a 3 min washout, these effects were reversible. The plot indicated the percentage of inhibition of IK after application of capsaicin (1–100 μM). b The G–V curve of IK did not shift in the absence and presence of capsaicin. c After application of 30 μM capsaicin, inactivation–voltage curve of IK significantly shifted to the hyperpolarizing direction

Use-Dependent Block of Capsaicin on IA and IK in TRPV1−/− Mice

The use-dependent block was measured by a series depolarizing pulses at different frequencies. Even in the normal solution, the reduction of IA became stronger with frequency of stimulation increasing from 0.5 to 1.7 Hz. This reduction could be explained by the slow recovery of IA from the inactivation state. When exposed to 30 μM capsaicin, the amplitude of IA was decreased in all simulative frequencies (tonic block), but no use-dependent block was found even at 1.7 Hz stimuli (Fig. 4). The amplitude of currents evoked by the nth impulse was normalized to the current evoked by the first impulse. Like IA, no use-dependent block was found for IK in the presence of capsaicin either (Fig. 5).

Fig. 4.

The use-dependent block of capsaicin on IA in TG neurons from TRPV1−/− mice. a The typical recordings show that in the presence of 30 μM Cap, IA was reversibly inhibited in different stimulation frequencies. b Exposed to 30 μM Cap, the amplitudes of IA were reduced in all stimulation frequencies. c The plots were normalized which set the amplitudes of IA trigged by first depolarizing pulse as 1, to compare use-dependent block at different frequencies under the control and capsaicin-application condition. As shown in the plots, in the presence of capsaicin, the block for IA was tonic block, but not use-dependent block

Fig. 5.

The use-dependent block of capsaicin on IK in TG neurons from TRPV1−/− mice. a The typical recordings were shown in the presence of 10 and 30 μM capsaicin for 3 min. b The amplitudes of IK were reduced in all stimulation frequencies in the presence of capsaicin (10 and 30 μM). c The plots were normalized which set the amplitudes of IK trigged by first depolarizing pulse as 1, to compare use-dependent block at different frequencies under the control and capsaicin-application condition. As shown in the plots, in the presence of capsaicin, the block for IK was tonic block, but not use-dependent block

Effects of Capsaicin on the IA and IK Recovery Time in TRPV1−/− Mice

To explore the modulation of capsaicin on the transition of the VGPCs from the inactivated state to the resting state, the recovery time course was measured in the absence and presence of capsaicin. TG neurons were stimulated with a double-pulses protocol with intervals varying between 2 ms and 2 s. In the presence of 30 μM capsaicin, the amplitude of IA and IK was reduced (Fig. 6a), but the recovery time (TAU) course of IA (Control: TAU = 0.007 ± 0.002 ms, n = 9; Capsaicin: TAU = 0.006 ± 0.001 ms, n = 7, P > 0.05) and IK (n = 9) did not significantly change (Fig. 6b).

Fig. 6.

The effects of capsaicin on recovery time of IA and IK in cultured TG neuron from TRPV1−/− mice. a Plots showed that amplitude of both IA and IK recovered as interval time increased in the absence and presence of 30 μM capsaicin. b Plots were normalized to compare time courses of recovery in the absence and presence of capsaicin

Role of Forskolin in Capsaicin-Mediated Inhibition of VGPCs in TRPV1−/− Mice

It is known that VGPCs are modulated by a variety of intracellular second messengers. It is reported that capsaicin (100 μM) attenuates transepithelial currents in human airway epithelial Calu-3 cells through TRPV1-independent and cAMP-dependent mechanisms (Hibino et al. 2011). To address whether the PKA pathway contributed to capsaicin-mediated inhibition of VGPCs in TRPV1−/− TG neurons, we studied the effects of capsaicin in the presence of forskolin, an adenylate cyclase agonist. After pre-application of 10 μM forskolin for 5 min, IK and IA were decreased by 8.21 ± 2.25 % (n = 7, paired t test, P < 0.05) and 9.36 ± 3.72 % (n = 8, paired t test, P < 0.05), respectively. As shown in Fig. 7, pre-application of forskolin, significantly decreased the inhibition of IK by capsaicin, whereas unaffected the inhibitions of IA by capsaicin. These results suggested the selective involvement of PKA pathway in the inhibition of IK by capsaicin.

Fig. 7.

Modulation of PKA pathway on the effects of VGPCs induced by capsaicin in TG neurons from TRPV1−/− mice. a The typical recordings show that the amplitude of IA was 12.85, 5.91, 5.95, and 5.98 nA before, during application of Cap (30 μM), After a 5 min pre-incubation with forskolin (10 μM) and subsequent addition of Cap (30 μM) and after 3 min wash, respectively. The histogram shows that pre-incubation with forskolin failed to affect the inhibition of IA by Cap (unpaired t test, P > 0.05). b Forskolin markedly decreased the inhibitions of IK by capsaicin. The amplitude of IK was 10.35, 4.80, 6.41, and 4.92 nA before, during application of Cap (30 μM), After a 5 min pre-incubation with forskolin (10 μM) and subsequent addition of Cap (30 μM) and after 3 min wash, respectively. The histogram shows the distinct difference in relative amplitude of IK between Cap (40.7 ± 4.4 %, n = 8) experiments and Cap + Forskolin (63.2 ± 5.6 %, n = 10) experiments. *P < 0.05 compared with the Cap experiments

Discussion

TG neurons are primary afferent neurons that carry sensory signals from the face, oral cavity, and nasal cavity to the medulla. Many nociceptive stimuli are known to change the neuronal excitability at peripheral nerve endings of the TG neurons, so in the present study, TG neurons were used as a pain model to study the capsaicin-induced tuning of VGPCs. Capsaicin was reported to block VGPCs in different kinds of cells and species at concentrations ranging from less than 1 μM to more than 100 μM (Petersen et al. 1987; Castle 1992; Kuenzi and Dale 1996; Kang et al. 2010; Chieng et al. 2006; Kinch et al. 2012; Kehl 1994). This immense variation in both cell kind and concentration of capsaicin implicates that different mechanisms may involve in the block of capsaicin on VGPCs. Our previous study shows that there are two mechanisms, selective effects dependent on capsaicin receptors and non-selective effects independent of capsaicin receptors, which may be involved in the blockages of capsaicin on IA in rat TG neurons. However, it is possible that different effects of capsaicin on IA result from heterogeneous expression of VGPCs subunits in CS and CIS neurons; the CS neurons are mainly of small- and medium-sized neurons in TG and DRG. Here we compared the effects of capsaicin in TRPV1+/+ with TRPV1−/− mice using neurons of the same size ranging from 15 to 22.5 μm. Neurons in this size range have long-duration action potentials, TTX-resistant sodium currents, and other receptors that indicate that they are nociceptors in our previous study (Cao et al. 2007).

First, In CS neurons of TRPV1+/+ mice, IA and IK were reduced by 52.3 ± 17.2 % and 43.4 ± 16.9 %, respectively, by 1 μM capsaicin and the effects could be reversed by capsazepine. Second, in CIS neurons of TRPV1+/+ mice, or TG neurons of TRPV1−/− mice, both IA and IK only were blocked less than 10 % by 1 μM capsaicin and the effects were not reversed by capsazepine. These data further confirm that the vast majority of the capsaicin-induced inhibition of IA and IK in CS neurons occurs as a consequence of the activation of TRPV1.

In the present experiment, we demonstrated that VGPCs, including IK and IA, were inhibited by capsaicin via TRPV1-independent pathway in TRPV1−/− TG neurons. TRPV1-independent inhibitory effects of high concentration capsaicin on voltage-gated sodium channels (VGSCs), including total and tetrodotoxin-resistant sodium currents, are also found in TRPV1−/− mice (Cao et al. 2007) and rat-cultured TG neurons (Liu and Simon 2003). Similarity to VGSCs, being accompanied the amplitude reduced, h-infinity curve of VGPCs also significantly shift to hyperpolarizing direction but without a shift of G-V curve. Different from VGSCs, even with very high concentration of capsaicin (30 μM) and very high frequency stimuli (1.7 Hz), use-dependent blockage is not yet induced for IA and IK. It is generally accepted that a drug-induced use-dependent block is attributed to the drug binding to a specific channel state (to the channel open stage, or to the inactivated state, thereby stabling the non-conducting channel state) (Savio-Galimberti et al. 2012; Takeda et al. 2006). Use-dependent block of capsaicin (30 μM) in neuronal Na+ channels is related to direct capsaicin binding via non-TRPV1 receptor within the open Na+ channel (Wang et al. 2007). It is not known whether there is a non-TRPV1 receptor of capsaicin within open K+ channels. And the newer hypothesis suggests that drug-induced stabilization of slow inactivation of channels should be partly responsible for use-dependence block (Silva and Goldstein 2013). In the present study, we found that the recovery time courses of IA and IK were not delayed, even at very high capsaicin concentration (30 μM), that might interpret why use-dependent blockage was not induced. Otherwise, we found dose-dependent inhibition effects of capsaicin on IA and IK were similar to linear in TRPV1−/− mice, but the linear inhibition did not necessarily mean non-specific effects. Regarding the inhibition of IA by capsaicin in CS neurons, the dose-dependent inhibition curves are different in our previous study (Liu and Simon 2003), and in the present study, it is possible that the species (rat versus mice) and dose of capsaicin differences may play role here.

It should be noted that the CS TRPV1-independent effects in TG neuron are complicated. On one hand, capsaicin inhibits VGSCs, which decreases the excitability of neurons, resulting in analgesic effects. On the other hand, capsaicin inhibits VGPCs, which increases the excitability of neurons and leads to the algetic effects. As is known that the abnormal excitability of nociceptor is mediated by changes in function of many ion channels including voltage-gated channels and receptors, therefore, the nociception induced by capsaicin is very likely an integrative result.

Capsaicin-sensitive mechanisms are composed of both TRPV1 dependent and independent pathways. The TRPV1-dependent mechanism for the action of capsaicin is well known. There is increasing evidence that some pharmacological roles of capsaicin are TRPV1-independent pathway (Surh and Kundu 2011). It has been shown that Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ (Kim et al. 2004), TRPV6 (Chow et al. 2007), and cAMP-dependent mechanisms (Hibino et al. 2011) are involved in TRPV1-independent effects of capsaicin. The PKA pathway has an important role in the modulation of ion channels involved in neuronal and nociceptor excitability. Here, we found that forskolin reduced the inhibitory effects of IK by capsaicin. Thus, it appears that PKA pathway is involved in the inhibition of IK by capsaicin via TRPV1-independent mechanism. In contrast to the situation observed in IK, in the presence of forskolin, the decrease of IA by capsaicin was unaffected. This differential regulation suggests that the effects of capsaicin on VGPCs in TRPV1−/− TG neurons are unlikely to arise from a non-specific effect on channel activity as a consequence of the adsorption of lipophilic capsaicin molecules to alter the cell membrane properties. Nevertheless, we have no sufficient evidence to indicate that VGPCs are inhibited after capsaicin induction of the PKA pathway via TRPV1-independent mechanism. Further experiments will be required to test this possibility.

In summary, in the present study by using TRPV1+/+ and TRPV1−/− mice, we confirm that capsaicin inhibits VGPCs in TG neurons through its action on TRPV1 dependent as well as TRPV1-independent pathway, and PKA pathway is selectively involved in the inhibition of IK by capsaicin. Moreover, inhibitory effects of capsaicin on IA and IK will cause nociceptors to become more excitable and in this manner may contribute to its sensitizing effects.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NNSF grant 30571537, 30271500, NIH grant GM-63577, and by Education Department grant of Hubei province B2013148.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

- VGPCs

Voltage-gated potassium channels

- TRPV1

Transient receptor potential vanilloid 1

- IA

Transient potassium currents

- IK

Sustained potassium currents

References

- Boudaka A, Worl J, Shiina T, Neuhuber WL, Kobayashi H, Shimizu Y, Takewaki T (2007) Involvement of TRPV1- dependent and -independent components in the regulation of vagally induced contractions in the mouse esophagus. Eur J Pharmacol 556:157–165 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brederson JD, Kym PR, Szallasi A (2013) Targeting TRP channels for pain relief. Eur J Pharmacol 00173:S0014–2999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calixto JB, Kassuya CA, Andre E, Ferreira J (2005) Contribution of natural products to the discovery of the transient receptor potential (TRP) channels family and their functions. Pharmacol Ther 106:179–208 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao XH, Cao XS, Xie H, Yang R, Lei G, Li F, Li A, Liu CJ, Liu LJ (2007) Effect of capsaicin on VGSCs in TRPV1−/− mice. Brain Res 1163:33–43 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castle NA (1992) Differential inhibition of potassium currents in rat ventricular myocytes by capsaicin. Cardiovasc Res 26:1137–1144 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caterina MJ, Leffler A, Malmberg AB, Martin WJ, Trafton J, Petersen-Zeitz KR, Koltzenburg M, Basbaum AI, Julius D (2000) Impaired nociception and pain sensation in mice lacking the capsaicin receptor. Science 288(5464):306–313 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chieng BC, Christie MJ, Osborne PB (2006) Characterization of neurons in the rat central nucleus of the amygdala: cellular physiology, morphology, and opioid sensitivity. J Comp Neurol 497:910–927 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chow J, Norng M, Zhang J, Chai J (2007) TRPV6 mediates capsaicin-induced apoptosis in gastric cancer cells-Mechanisms behind a possible new ‘hot’ cancer treatment. Biochim Biophys Acta 1773:565–576 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer MJ, Btesh J, McNaughton PA (2013) Disrupting sensitization of transient receptor potential vanilloid subtype 1 inhibits inflammatory hyperalgesia. J Neurosci 33:7407–7414 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hakim AW, Dong XD, Svensson P, Kumar U, Cairns BE (2009) TNFalpha mechanically sensitizes masseter muscle afferent fibers of male rats. J Neurophysiol 102(3):1551–1559 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hibino Y, Morise M, Ito Y, Mizutani T, Matsuno T, Ito S, Hashimoto N, Sato M, Kondo M, Imaizumi K, Hasegawa Y (2011) Capsaicinoids Regulate Airway Anion Transporters through Rho Kinase-and Cyclic AMP-Dependent Mechanisms. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 45(4):684–691 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeub M, Emrich M, Pradier B, Taha O, Gailus-Durner V, Fuchs H, de Angelis MH, Huylebroeck D, Zimmer A, Beck H, Racz I (2011) The transcription factor Smad-interacting protein 1 controls pain sensitivity via modulation of DRG neuron excitability. Pain 152:2384–2398 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang S, Wu C, Banik RK, Brennan TJ (2010) Effect of capsaicin treatment on nociceptors in rat glabrous skin one day after plantar incision. Pain 148:128–140 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kehl SJ (1994) Block by capsaicin of voltage-gated K + currents in melanotrophs of the rat pituitary. Br J Pharmacol 112:616–624 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim CS, Park WH, Park JY, Kang JH, Kim MO, Kawada T, Yoo H, Han IS, Yu R (2004) Capsaicin, a spicy component of hot pepper, induces apoptosis by activation of the peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ in HT-29 human colon cancer cells. J Med Food 7(3):267–273 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinch DC, Peters JH, Simasko SM (2012) Comparative pharmacology of cholecystokinin induced activation of cultured vagal afferent neurons from rats and mice. PLoS ONE 7:e34755 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuenzi FM, Dale N (1996) Effect of capsaicin and analogues on potassium and calcium currents and vanilloid receptors in Xenopus embryo spinal neurones. Br J Pharmacol 119:81–90 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu L, Simon SA (2003) Modulation of IA Currents by Capsaicin in Rat Trigeminal Ganglion Neurons. J Neurophysiol 89:1387–1401 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu L, Oortgiesen M, Li L, Simon SA (2001) Capsaicin inhibits activation of voltage-gated sodium currents in capsaicin-sensitive trigeminal ganglion neurons. J Neurophysiol 85:745–758 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu L, Yang T, Bruno MJ, Andersen OS, Simon SA (2004) Voltage-gated ion channels in nociceptors: modulation by cGMP. J Neurophysiol 92(4):2323–2332 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lundbæk JA, Birn P, Tape SE, Toombes GES, Søgaard R, Koeppe Roger E, Gruner SM II, Hansen AJ, Andersen OS (2005) Capsaicin Regulates Voltage-Dependent Sodium Channels by Altering Lipid Bilayer Elasticity. Mol Pharmacol 68:680–689 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maljevic S, Lerche H (2013) Potassium channels: a review of broadening therapeutic possibilities for neurological diseases. J Neurol 260:2201–2211 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malykhina AP, Qin C, Lei Q, Pan XQ, Greenwood-Van Meerveld B, Foreman RD (2013) Differential effects of intravesical resiniferatoxin on excitability of bladder spinal neurons upon colon-bladder cross-sensitization. Brain Res 1491:213–224 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nie A, Wei C, Meng Z (2009) Sodium metabisulfite modulation of potassium channels in pain-sensing dorsal root ganglion neurons. Neurochem Res 34:2233–2242 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palazzo E, Luongo L, de Novellis V, Rossi F, Marabese I, Maione S (2012) Transient receptor potential vanilloid type 1 and pain development. Curr Opin Pharmacol 12:9–17 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petersen M, Pierau FK, Weyrich M (1987) The influence of capsaicin on membrane currents in dorsal root ganglion neurons of guinea-pig and chicken. Pflugers Arch 409:403–410 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Premkumar LS, Abooj M (2013) TRP channels and analgesia. Life Sci 92:415–424 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Savio-Galimberti E, Gollob MH, Darbar D (2012) Voltage-gated sodium channels: biophysics, pharmacology, and related channelopathies. Front Pharmacol 3:124 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sculptoreanu A, Yoshimura N, de Groat WC (2004) KW-7158 [(2S)-(+)-3, 3, 3-trifluoro-2-hydroxy-2-methyl-N- (5, 5, 10-trioxo-4, 10-dihydro thieno [3,2-c][1] benzothiepin-9-yl) propanamide] enhances A-type K + currents in neurons of the dorsal root ganglion of the adult rat. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 310:159–168 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silva JR, Goldstein SA (2013) Voltage-sensor movements describe slow inactivation of voltage-gated sodium channels I: wild-type skeletal muscle Na(V)1.4. J Gen Physiol 141:309–321 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart T, Beyak MJ, Vanner S (2003) Ileitis modulates potassium and sodium currents in guinea pig dorsal root ganglia sensory neurons. J Physiol 552:797–807 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Surh YJ, Kundu JK (2011) Molecular mechanisms of chemoprevention with capsaicinoids from chili peppers. Vegetables, Whole Grains, and Their Derivatives in Cancer Prevention. Springer, Netherlands, pp 123–142 [Google Scholar]

- Takeda M, Tanimoto T, Ikeda M, Nasu M, Kadoi J, Yoshida S, Matsumoto S (2006) Enhanced excitability of rat trigeminal root ganglion neurons via decrease in A-type potassium currents following temporomandibular joint inflammation. Neuroscience 138:621–630 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang SY, Mitchell J, Wang GK (2007) Preferential block of inactivation-deficient Na+ currents by capsaicin reveals a non-TRPV1 receptor within the Na+ channel. Pain 127(1):73–83 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiong Z, Liu Y, Hu L, Ma B, Ai Y, Xiong C (2013) A rapid facilitation of acid-sensing ion channels current by corticosterone in cultured hippocampal neurons. Neurochem Res 38:1446–1453 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu GY, Winston JH, Shenoy M, Yin H, Pasricha PJ (2006) Enhanced excitability and suppression of A-type K + current of pancreas-specific afferent neurons in a rat model of chronic pancreatitis. American Journal of Physiology-Gastrointestinal and Liver. Physiology 291:424–431 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]