Abstract

Objective

This review identifies and evaluates the efficacy of behaviour-change techniques explicitly aimed at walking in individuals with intermittent claudication.

Design

Systematic narrative review of randomised-controlled trials (RCTs).

Methods

An electronic database search was conducted up to December 2012. RCTs comparing interventions incorporating explicit behaviour-change techniques with usual care, walking advice or exercise therapy for increasing walking in people with intermittent claudication were included. Studies were evaluated using the Cochrane Collaboration risk of bias tool. The primary outcome variable was maximal walking ability at least 3 months after the start of an intervention. Secondary outcome variables included pain-free walking ability, self-report walking ability and daily walking activity.

Results

A total of 3 575 records were retrieved. Of these, 6 RCTs met the inclusion criteria. Due to substantial heterogeneity between studies, a meta-analysis was not conducted. Overall, 11 behaviour-change techniques were identified; barrier identification with problem solving, self-monitoring and feedback on performance were most frequently reported. There was limited high-quality evidence and findings were inconclusive regarding the utility of behaviour-change techniques for improving walking.

Conclusions

There is a dearth of high-quality research examining behaviour-change techniques for increasing walking among people with intermittent claudication. Rigorous, fully-powered trials are required that control for exercise dosage and supervision in order to isolate the effect of behaviour-change techniques alongside exercise therapy.

Keywords: health behaviour, intermittent claudication, walking, exercise adherence

INTRODUCTION

Intermittent claudication (IC) caused by lower-extremity peripheral arterial disease (PAD) is a debilitating condition, affecting walking ability, health status and quality of life.1-3 In addition to adequate treatment of the underlying arteriosclerotic disease, improving walking ability is an important clinical aim.

Exercise, and particularly walking, is a key component to disease management,4,5 with gains of up to 200% in maximal walking ability achieved following supervised exercise therapy (SET).6 SET is frequently treadmill-based and conducted in healthcare facilities where patients are supervised by healthcare professionals. Guidelines recommend SET on at least 3 days per week for at least 30 minutes.4 Over the long-term, SET might be more effective than standard pharmaceutical therapy,7,8 and endovascular treatment or surgical treatment6,7 in improving walking ability.

However, the long-term effectiveness of SET relies on adherence to exercise, which is variable,6 and the impact on long-term unsupervised walking behaviour in the community is unclear.6 Moreover, recent international data suggests that less than one-third of vascular surgeons have access to SET to which patients can be referred9. As a result of these resource limitations, individuals often receive only instruction to walk in their community, although fewer than one-half of IC patients follow such advice.10 People with IC report lack of specific instructions, uncertainty regarding the outcome of walking exercise, the presence of comorbidities, and pain tolerance among barriers to engaging in regular walking.10,11

Adherence to a home-based exercise prescription requires the individual to change their behaviour, either by adopting a new regimen or altering their current exercise. Increasing walking behaviour in people with IC presents a particular challenge as walking gives rise to pain and may not seem either logical or necessary to the individual. While walking advice or SET may support behaviour change, for example, by providing information on how to perform walking exercise or through the provision of social support, data on activity levels among individuals with IC10,12 suggest that more deliberate strategies are necessary for lifestyle changes to occur. Therefore, skills for regulating thoughts and actions must be learned.13

Specific behaviour-change techniques (BCTs) based on existing psychosocial models of health-related behaviours have been identified, which could be implemented in clinical practice in order to increase unsupervised exercise, such as walking.14 These target individual motivation, and range from simple tasks such as keeping a diary to monitor activity or setting behavioural goals, to complex psychological techniques including motivational interviewing (discussing and exploring with the individual ways to minimizes resistance and ambivalence toward behaviour change)15 and action planning (detailed preparation of when, where and how the individual will engage in a behaviour).16 Therefore, if it is possible to identify techniques, or combinations of techniques, that have been successfully applied to increase walking in people with IC, then these could be applied in addition to walking prescriptions (that is, walking advice or SET) in order to achieve greater outcomes.

To date, evidence from interventions employing BCTs among individuals with IC has not been systematically evaluated. We conducted a systematic review of randomized controlled trials (RCTs) to evaluate whether BCTs improve measures of functional walking distances as well as walking behaviour among individuals with IC, and to identify if any particular techniques were successful.

METHODS

Eligibility criteria

Studies were eligible for inclusion if they were RCTs of individuals diagnosed with PAD and IC.4 Intervention groups must have received treatment incorporating at least one BCT, as defined by Michie et al.,14 that explicitly targeted walking behaviour. Walking advice was considered as part of usual care and was not included as a behaviour-change technique. Eligible control groups included patients receiving walking advice alone, usual care or attention placebo, but no administration of BCTs. Studies were excluded if both intervention and control groups received BCTs or if outcome variables were not reported at least 3 months following the start of an intervention.

Primary outcome

The primary outcome variable was maximal walking ability (MWA) assessed by treadmill or corridor walk test. MWA is a reliable quantitative marker of ambulatory performance in people with IC,17 and represents the distance or duration an individual can walk before they need to stop and rest.

Secondary outcomes

Secondary outcome variables included: pain-free walking ability (PFWA) assessed by treadmill or corridor walk test, which represents the distance or duration an individual can walk before they report the onset of pain; self-report walking ability, assessed by distance and speed scores on the Walking Impairment Questionnaire (WIQ),18 and daily walking activity, assessed by self-report or using an activity monitor. All outcome variables were evaluated at least 3 months following the start of an intervention, with the longest follow-up assessment reported.

Data sources and search strategies

An electronic database search (Supplementary Figure 1) was conducted using Medline, PsychINFO, Embase, CINAHL and Web of Science and by cross-checking reference lists of retrieved full-text articles. The OpenSINGLE database was searched for any appropriate grey literature and the active register of the metaRegister of Controlled Trials was searched for in-progress and unpublished trials. No language restrictions were imposed and databases were searched from their earliest records to December 2012. Search results were downloaded into bibliographic software (EndNote X6; Thompson Reuters, New York, NY, USA).

Search terms included MeSH, keyword and wild-card terms located in the title or abstract for three broad concepts reflecting the disease (e.g., intermittent claudication, peripheral arterial disease), psychological interventions or variables (e.g., behaviour modification, motivation, intervention) and outcome (e.g., walking, exercise).

Study selection

Titles and abstracts of records were screened for eligibility by two investigators (MG and LB), and the full texts of retained articles were reviewed by two investigators (MG and LB) independently using a bespoke screening tool that was designed and piloted a priori. Disagreement between reviewers was resolved following discussion.

Data collection and computation

A data extraction tool was developed based on a template from the Cochrane Peripheral Vascular Diseases Review Group. This was pilot-tested on a selection of studies and refined as necessary. Data was collected on methods, study design, participants, intervention components and key outcome variables. At least two of four reviewers (MG, CW, LB and SJB) extracted data from all included studies. Disagreement was resolved by discussion.

Mean differences (MD) and 95% CIs were calculated for data on MWA, PFWA and daily walking activity, where possible, using Review Manager 5 (Cochrane IMS); if sufficient data to calculate MD were unavailable, percentage change scores were calculated: ([baseline score − follow-up score]/baseline score)×100. Scores for self-report walking ability were converted from ratio or percentage values to reflect a range from 0–100 on the WIQ.

Risk of bias in individual studies and level of evidence

Study quality was evaluated using the Cochrane Collaboration tool for assessing risk of bias.19 Individual RCTs were rated as having high risk of bias (i.e., ‘low-quality’ trials) or low to moderate risk of bias (i.e., ‘high-quality’ trials) if there was evidence for the presence of ≥3 or <3 sources of bias, respectively. In addition, RCTs were appraised using a 27-item checklist developed by Downs and Black,20,21 which provided a broader evaluation of study quality, including reporting, internal and external validity, and power. The maximum possible score for study quality using this scale is 31. The cumulative level of evidence from multiple studies, defined as ‘strong’, ‘moderate’, ‘limited’, ‘conflicting’ or ‘none’, was determined for each outcome variable in accordance with recommendations by van Tulder et al.22

RESULTS

Study selection

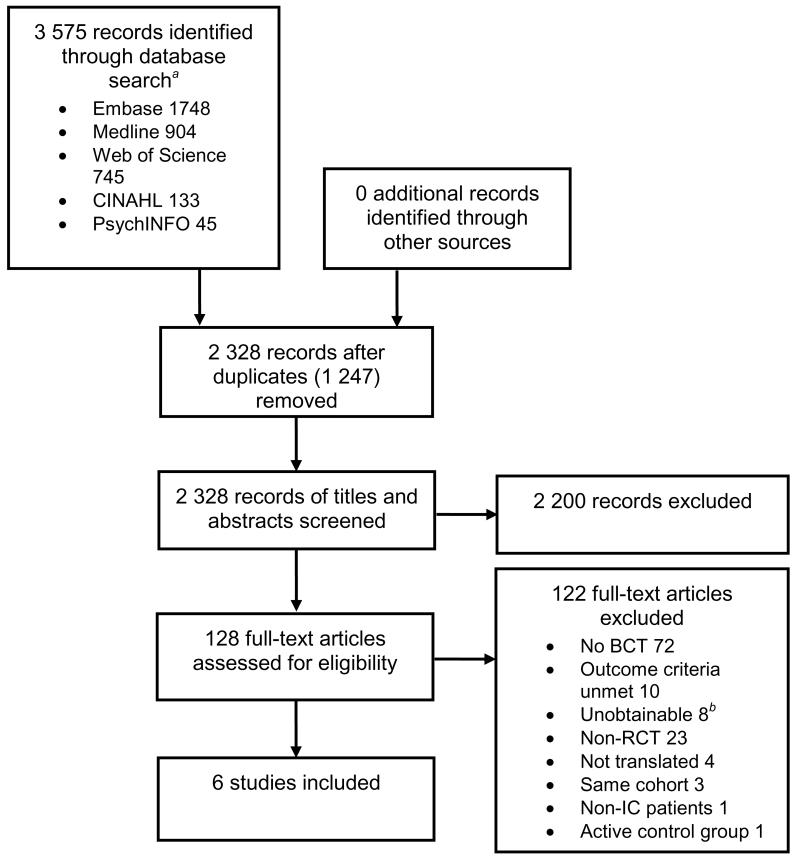

Six studies were identified for inclusion in the review.8,23-27 The initial database search resulted in 3 575 identified records. After duplicates were removed, 2 328 records remained, of which 2 200 studies were excluded based on the content of their titles and abstracts. Full texts of the remaining 128 articles were reviewed, of which a further 122 articles were excluded (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Flow diagram illustrating the process of study selection for a systematic review on behaviour-change techniques and walking in individuals with peripheral arterial disease

aNo records were identified from the OpenSINGLE database or metaRegister of Controlled Trials. bUnavailable through a national library catalogue. Abbreviations: BCT, behaviour-change technique.

Due to the heterogeneity of behaviour-change interventions, exercise prescriptions and outcome measures used, a narrative synthesis of the six included studies was conducted without meta-analysis.

Characteristics of included studies

Study design and participants

Six RCTs evaluating BCTs to increase walking in IC, with a total of 461 participants, were included (Table 1). Two RCTs were pilot studies26,27 and one was a PhD thesis.25 The number of participants ranged from 1927 to 145.23 Mean age was 67.3 years and 64% (n=274/430) were male, reflecting the age and gender distribution of PAD in the general population.4 Baseline clinical measures were similar between control and intervention groups in all included studies, with the exceptions that one study reported a significantly higher MWA25 and one reported greater medication use for IC23 among the control group participants.

Table 1.

Characteristics of randomized controlled trials included in the systematic review

| First author | Participants (n=461) | Exercise intervention | BCTs used | BCT delivery | Control | Outcome measure |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cunningham1 | n=58 (67% M), mean 65.3 years, 36% current smokers, mean ABI 0.70, early IC. | Walking advice +BCT. | Information on consequences of walking exercise, behavioural goal setting, action planning, barrier identification/problem solving, motivational interviewing. | Individual consultation with a trainee health psychologist (2× 1 h, 1 week apart) delivered at home. | Walking advice plus attention placebo. | DWA (step activity monitor) at 4 months. |

| Gardner2 | n=119 (48% M), mean 65 years, 10% current smokers, mean ABI 0.73, established IC. | Walking advice +BCT. | Self-monitoring, performance feedback. | Individual consultation with an exercise physiologist (7× 15 min, 2×/month). | Walking advice.a | MWA and PFWA (graded progressive treadmill testb), SRWA and DWA (step activity monitor) at 3 months. |

| Cheetham3 | n=59 (73% M), mean 67 years, 100% current or ex-smokers, mean ABI 0.69, established IC. | Walking advice and SET (1× 30 min/week for 6 months) +BCT. | Information on consequences of walking exercise. | Motivation class (1× 5–10 min/week for 6 months) delivered in conjunction with SET. | Walking advice. | MWA (constant-load treadmill testc) up to 12 months. |

| Christman4 | n=30 (55% M), mean 66.9 years, 47% current smokers, mean ABI 0.61, established IC. | Walking advice +BCT. | Barrier identification/problem solving, self-monitoring, performance feedback, behavioural contract, follow-up prompts, planning social support. | Small group counselling (1× 1 h/week for 12 weeks). | Walking advice. | MWA and PFWA (graded progressive treadmill testd) up to 6 months. |

| Collins5 | n=145 (69% M), mean 66.5 years, 14% current smokers, mean ABI 0.95, DM and established IC. | Walking advice and SET (1×50 min/week for 6 months) +BCT. | Behavioural goal setting, barrier identification/ problem solving, self-monitoring, performance feedback, prompt practice of walking, follow-up prompts, planning social support. | Individual consultation (1× at baseline), practice exercise sessions (2× 1 h), follow-up telephone consultation (1× biweekly for 6 months). | Usual care plus attention-placebo. | MWA (graded progressive treadmill testb) and SRWA at 6 months. |

| Quirk6 | n=19 (74% M), mean 73.2 years, 32% current smokers, mean ABI not reported, established IC. | Walking advice +BCT.e | Motivational interviewing | Individual consultation (up to 4× 1 h) | Walking advice. e | DWA (self-report)f |

This was a three-arm trial and included a group receiving SET for which data are not presented.

Gardner maximal treadmill test:7 3.2 km/h (2.0 mph) constant speed, baseline 0% grade, increasing 2% every 2 min up to 14% at 16 min; maximum distance 0.8 km (0.5 mi).

3.0 km/h at a 12% grade up to 15 min.8

Baseline 1.6 km/h (1.0 mph) and 5% grade, increasing in 5 min intervals to 4.0 km/h (2.5 mph) and 10% grade.

Confirmed by personal communication with author.

International Physical Activity Questionnaire, brief version

Abbreviations: ABI, ankle-brachial index; BCT, behaviour-change technique; DM, diabetes mellitus; DWA, daily walking activity; IC, intermittent claudication; M, male; MWA, maximal walking ability; PAD, peripheral arterial disease; PFWA, pain-free walking ability; SDCQ, San Diego Claudication Questionnaire; SET, supervised exercise therapy; SRWA, self-report walking ability (assessed by the WIQ).

Intervention composition and setting

BCTs were administered in conjunction with walking advice in four studies 8,25-27 and with walking advice plus SET in two studies.23,24 Interventions ranged in the number of BCTs applied from one24,27 up to seven.23 Two interventions were delivered through group sessions24,25 and four during individual consultation.8,23,26,27 Among the interventions delivered on an individual basis, two were delivered at a research centre or hospital,8,27 one included a baseline consultation plus telephone follow-up23 and one was delivered in participants’ homes.26

Identified behaviour-change techniques

Overall, 11 BCTs14 were identified in the included studies (Table 2). The most frequent techniques reported were prompting self-monitoring of behaviour (n=3),8,23,25 feedback on performance (n=3)8,23,25 and barrier identification and problem solving (n=3).23,25,26 Other BCTs included motivational interviewing (n=2),26,27 providing follow-up prompts (n=2),23,25 information on the consequences of the behaviour in general (n=2),24,26 behavioural goal setting (n=2)23,26 and planning social support (n=2).23,25 Action planning,26 use of a behavioural contract,25 and prompting practice of the behaviour23 were each reported once.

Table 2.

Summary of behaviour-change techniques identified in included studies

| Behaviour-change technique | Definitiona |

|---|---|

| Prompt self-monitoring of behaviour | Individuals is asked to keep a record (e.g., diary) of specified behaviour as a method of changing behaviour (i.e., includes explicit intervention components, rather than a component of outcome measures for research purposes.) |

| Provide feedback on performance | Individual is provided data about their own recorded behaviour or receives comments on their behavioural performance |

| Barrier identification / problem solving | Individual is prompted to think about potential barriers (e.g., behavioural, cognitive, emotional, environmental, social and/or physical) and identify ways of overcoming them. |

| Use of follow-up prompts | Intervention components are gradually reduced in intensity, duration and/or frequency over time (e.g., letters or telephone calls are used instead of face-to-face consultations) |

| Provide information on consequences of the behaviour in general | Information about the relationship between the behaviour and its possible or likely consequences in the general case, but not personalised for the individual (e.g., usually based on epidemiological data) |

| Goal setting (behaviour) | Individual is encouraged to make a behavioural resolution (i.e., to decide to change or maintain change) |

| Plan social support / social change | Individual is prompted to plan how to elicit social supportto achieve their target behaviour or outcome (e.g., includes support from family, friends or those providing the intervention). |

| Action planning | Involves detailed planning of what the person will do, including whenor how frequently, in which situation and/or where to engage in behaviour |

| Motivational interviewing | A clinical method including specific techniques that prompt the individual to engage in change talk in order to minimise resistance and resolve ambivalence to change |

| Agree behavioural contract | A written agreement on the performance of an explicitly specified behaviour, including a record of the resolution that is witnessed by another |

| Prompt practice | Individual is prompted to rehearse and repeat the behaviour, parts of the behaviour or preparatory behaviours numerous times (e.g., building habits or routines) |

Definitions are according to the taxonomy of behaviour-change techniques defined by Michie et al.9

Control groups

Control groups received walking advice in four studies,8,24,25,27 and walking advice or usual care plus attention placebo in two studies.23,26 One study8 was a three-arm trial comparing home-based exercise therapy with SET or walking advice; for the purposes of this review, we report results of comparisons between home-based exercise therapy and walking advice only, as the home-based exercise therapy group were engaged in self-monitoring and received feedback on performance as BCTs, as per the inclusion criteria.

Outcome

Three studies evaluated walking ability (MWA or PFWA) by treadmill protocol using a graded progressive treadmill test,8,23,25 and one used a constant load treadmill test.24 Two RCTs included data on self-reported walking ability using the WIQ.8,23 Three studies reported daily walking activity, two which used step activity monitors8,26 and one which used a standard questionnaire (International Physical Activity Questionnaire) to assess self-reported walking activity (Table 1).

Risk of bias in individual studies

The mean (range) score using the quality assessment tool by Downs and Black20 was 20 (12–26). Possible bias occurred in several studies because of inadequate allocation concealment23-25,27 and none of the included studies blinded outcome assessment (Table 3).

Table 3.

Risk of bias in randomized-controlled trials

| First author | Source of biasa | Summary risk of biasb | Quality Indexc | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Random sequencegeneration | Allocation concealment | Participant and personnel blinding | Blinded outcome assessment | Incomplete outcome data | Selective reporting | |||

| Cheetham3 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | High | 21 |

| Christman4 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | High | 15 |

| Collins5 | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | High | 23 |

| Cunningham1 | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | No | Low | 24 |

| Gardner2 | No | No | Yes | Yes | No | No | Low | 26 |

| Quirk6 | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | High | 12 |

The presence or potential presence of a source of bias is indicated as ‘yes’.

Summary risk of bias was determined using the Cochrane Collaboration tool for assessing risk of bias.10

Studies were rated as having high risk of bias (i.e., ‘low-quality’ trials) or low to moderate risk of bias (i.e., ‘high-quality’ trials) if there was evidence for the presence of ≥3 or <3 sources of bias, respectively.

Quality index scores were determined using the quality appraisal tool developed by Downs and Black;11 scores range from 0–31, with higher scores indicating higher study quality and a lower risk of bias.

Effect of interventions

Maximal walking ability at least 3 months after the start of an intervention

Four studies reported data on MWA (Table 4 and Supplementary Table 1).8,23-25 One high-quality trial reported significantly greater improvements in MWA at 3 months in the intervention versus control groups (MD Δ 134.0 s [95% CI 39.7 to 228.3]; P = 0.005).8 That study compared a walking advice plus BCTs with walking advice alone. Among low-quality trials, one study reported improvements in 3-month MWA following BCTs plus walking advice and weekly SET versus walking advice alone (median Δ 130% versus control 70%; P < 0.001).24 Two low-quality RCTs demonstrated no benefit of intervention versus control on MWA. One showed no difference 3 months following BCTs plus walking advice compared with walking advice alone (MD −3.9 min [95% CI −8.2 to 1.1]; P = 0.13)25 and one showed no difference at 6 months following BCTs plus walking advice and weekly SET versus a non-exercise attention-control group (MD 14.7 m [95% CI −69.0 to 39.6]; P = 0.60).23

Table 4.

Data extracted from included studies

| First author | Outcome | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Maximal walking ability | Pain-free walking ability | Self-report walking ability | Daily walking activity | ||

| Distance | Speed | ||||

| Cunningham1 | – | – | – | – | Greater change in stepstaken by intervention group(1 358 steps) versus control (−227 steps) at follow-up; P <0.001 |

| Gardner (versuswalking advice) 2 | Greater change in walking time in intervention group(124±193 s) versus control (−10±176 s); P <0.05 | Greater change in walking time in intervention group(134±197 s)versus control (−16±125 s); P <0.05 | P = NS | P = NS | P = NS |

| Cheetham3 | Greater walking distance in intervention group(median 304 m) versus control (175 m); P <0.001. | – | – | – | – |

| Christman4 | P = NS. | P = NS. | – | – | – |

| Collins5 | P = NS | P = NS | P = NS | Greater change in score for intervention group(Δ5.7±18.7) versus control (−1.9±23.9); P = 0.034. a | – |

| Quirk6 | – | – | – | – | P = NS |

Data are presented as intervention versus control and represent mean±SD unless indicated otherwise.

SD derived from data published as SE.

Abbreviations: NS, non-significant.

Pain-free walking ability at least 3 months following the start of an intervention

Three studies reported data on PFWA (Table 4 and Supplementary Table 1). One high-quality trial8 reported greater improvements in PFWA at 3 months following BCTs plus walking advice compared with walking advice alone (MD Δ 150.0 s [95% CI 65.5 to 234.5]; P = 0.0005). Among low-quality trials, there was no difference in PFWA at 3 months following BCTs plus walking advice compared with walking advice alone (MD −2.0 min [95% CI −5.7 to 1.7]; P = 0.29)25 or at 6 months following BCTs plus walking advice and weekly SET versus an attention placebo group (MD 14.4 m [95% CI −47.5 to 76.3]; P = 0.65).23

Self-report walking ability at least 3 months following the start of an intervention

Data on self-report walking ability was available from two studies (Table 4 and Supplementary Table 1). One high-quality trial found no difference at 3 months in self-report walking ability following BCTs plus walking advice (mean ±SD Δ for distance 10.0±25.0 and speed 11.0±22.0) versus walking advice alone (mean ±SD Δ for distance 1.0±34.0 and speed 4.0±25.0; both P = NS).8 One low-quality trial reported mixed findings. There was a greater improvement in self-report walking speed (mean ±SE Δ 5.7±2.2 versus control 1.9±2.8; P = 0.034), but not walking distance (mean ±SE Δ 5.6±3.5 versus control 1.4±3.3; P = 0.383) following BCTs plus walking advice and weekly SET versus an attention placebo.23

Daily walking activity at least 3 months following the start of an intervention

Data on daily walking activity was available from three studies, including two high-quality trials (Table 4 and Supplementary Table 1). In one high-quality study, change in mean 6-day step count was greater following BCTs plus walking advice versus an attention placebo plus walking advice (MD 1 674.2 steps [95% CI 156.0 to 3 188.4]; P = 0.03).26 In a second high-quality study, there was no difference in mean 7-day activity time following BCTs plus walking advice versus walking advice alone (MD −1 min/day [95% CI −41.1 to 39.1]; P = 0.96).8 In a low-quality pilot RCT, BCTs did not affect self-reported daily walking activity.27

DISCUSSION

This systematic review is the first evaluation of BCTs alongside exercise therapy for improving walking in individuals with IC. The existing evidence is limited to a small number of mostly low-quality trials using 11 BCTs, and there is insufficient evidence to draw conclusions on the effectiveness of these strategies for improving maximal walking ability. Given that access to SET and adherence to walking advice is limited among individuals with IC,9,10 this is an important finding as it highlights the need for more rigorous trials of behaviour-change interventions for this population.

While data from two high-quality trials demonstrate that BCTs supplementary to exercise prescription improved maximal and pain-free walking ability8 and increased daily walking activity,26 further evidence from four low-quality trials was conflicting. The high-quality trials were more recent publications, and may reflect improvements in study design and reporting, and a growing recognition of the need to support behaviour-change among IC patients. However, findings of both trials were at risk of bias due to lack of blinding of the outcome assessor, which may be important given that treadmill walking performance could be influenced by interaction with personnel. In addition, one trial was at risk of selection bias because there was no indication of allocation concealment.

While RCTs are considered the gold-standard for systematically evaluating the existing evidence, poor design and possible bias can reduce the robustness of data.28,29 In addition, RCTs often lack ecological validity, limiting the transferability of their findings to the clinical setting. Interestingly, before-and-after studies and audits of BCTs consistently report improvements in MWA among people with PAD.30-37

Possible explanations for the conflicting findings include the use of unstandardized treadmill testing protocols for measuring outcome,25 heterogeneous patient samples, for example patients in one trial concomitantly had diabetes mellitus23, which could influence exercise response.38,39 Moreover, while four 23,25-27 of the included studies were designed with the primary objective to examine the effect of BCTs on walking, two studies8,24 did not deliberately evaluate BCTs, thus compromising their quality appraisal in this review.

Patient perceived walking performance is an important clinical outcome, as pain-related symptoms are largely subjective and because no minimal clinically important differences for changes in PFWA or MWA have been established. In the current review, one high-quality study8 reported no change in self-report walking ability, despite improvements in PFWA and MWA, suggesting that BCTs might improve walking performance, but not patient perceptions of their walking ability, which may be more meaningful to them. Future studies evaluating BCTs should incorporate outcome measures reflecting the patient perception of walking capacity, together with more objective measures.

This review identifies a total of 11 BCTs, which were applied to increase walking in individuals with IC. Successful BCTs included self-monitoring, for example encouraging the patient to keep a diary of walking behaviour, providing feedback on walking performance, and helping the patient to identify barriers to walking and solutions to overcoming them. These techniques are useful for increasing an individual’s confidence in their ability to perform walking exercise and can be easily incorporated into clinical practice by healthcare professionals when discussing exercise, particularly home-based walking advice among people with IC. However, there are at least 29 additional theory-based techniques classified by Michie et al.,14 and possibly more unclassified techniques, that have not been applied to increase walking among individuals with IC, which warrant investigation.

Limitations to the included studies meant statistical synthesis of the data could not be performed because of a high degree of clinical and methodological heterogeneity, primarily due to variations in intervention protocol and setting between studies, and lack of control for these factors within studies. In addition, in two studies,23,24 where BCTs were provided alongside SET, it difficult to distinguish the effects of BCTs above and beyond the benefits of the exercise alone. However, both studies provided only one supervised exercise session per week, which is a suboptimal exercise dose that does not meet guidelines for SET for patients with IC.4,40 Thus, it is possible that the change in walking ability is not solely attributable to SET in these studies, and that BCTs targeting self-directed walking activity might influence outcomes. Data from the study by Gardner et al.,8 which applied BCTs to increase self-directed walking, demonstrate that BCTs have the potential to increase participation such that individuals achieve gains in walking ability that are at least comparable to SET.

BCTs are intended to target and modify known motivational factors, for example, a person’s beliefs about walking and the outcome of performing it, or their ability to carry out walking as exercise. In order to evaluate the effectiveness of BCTs, it is necessary to determine whether the targeted psychosocial constructs change over the course of an intervention. Because the studies included in this review did not evaluate the psychosocial constructs underpinning the BCTs implemented, it was not possible to determine whether the intervention successfully altered the psychosocial variables or if other factors influenced walking. Moreover, as most interventions combined multiple BCTs, the independent effects of each could not be determined.

In summary, there is limited evidence from one high-quality RCT supporting BCTs for increasing MWA and PFWA, and from one high-quality RCT suggesting BCTs might be beneficial for increasing daily walking activity among people with IC. Eleven BCTs were identified and several, in particular self-monitoring, feedback on performance and barrier identification with problem solving, could be easily combined with exercise prescription and walking advice in clinical practice. Future high-quality trials should explore these and other BCTs, and should evaluate changes in psychosocial variables that are targeted by specific techniques.

Supplementary Material

Statement: What this paper adds?

Provides the first systematic evaluation of behaviour-change techniques in addition to exercise therapy on walking capacity and behaviour in patients with intermittent claudication

Identifies 11 behaviour-change techniques that have been applied among individuals with intermittent claudication in order to increase walking

Barrier identification with problem solving, self-monitoring and feedback on performance are behaviour-change techniques that could be easily applied in clinical practice when prescribing exercise or giving advice to walk

There is a need for high-quality trials examining the effectiveness of behaviour-change techniques in addition to exercise therapy for improving patient outcomes

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors would like to thank Charlotte Krahé for assisting with translation of manuscripts to English and Sarah Jane Besser for assisting with data extraction.

Funding Funding for this study was provided by the Dunhill Medical Trust.

Footnotes

Competing interests The authors declare none.

Appendix 1. Supplementary Figure 1. A representative search strategy conducted in Medline within the Ovid interface.

Appendix 2. Supplementary Table 1. Data extracted from included studies.

REFERENCES

- 1.Regensteiner JG, Hiatt WR, Coll JR, Criqui MH, Treat-Jacobson D, McDermott MM, et al. The impact of peripheral arterial disease on health-related quality of life in the Peripheral Arterial Disease Awareness, Risk, and Treatment: New Resources for Survival (PARTNERS) Program. Vasc Med. 2008;13(1):15–24. doi: 10.1177/1358863X07084911. Epub 2008/03/29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McDermott MM, Greenland P, Ferrucci L, Criqui MH, Liu K, Sharma L, et al. Lower extremity performance is associated with daily life physical activity in individuals with and without peripheral arterial disease. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2002;50(2):247–55. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2002.50055.x. Epub 2002/05/25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gardner AW, Montgomery PS, Killewich LA. Natural history of physical function in older men with intermittent claudication. J Vasc Surg. 2004;40(1):73–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2004.02.010. Epub 2004/06/26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Norgren L, Hiatt WR, Dormandy JA, Nehler MR, Harris KA, Fowkes FG, et al. Inter-Society Consensus for the Management of Peripheral Arterial Disease (TASC II) Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2007;33(Suppl 1):S1–S75. doi: 10.1016/j.ejvs.2006.09.024. Epub 2006/12/05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hirsch AT, Haskal ZJ, Hertzer NR, Bakal CW, Creager MA, Halperin JL, et al. ACC/AHA Guidelines for the management of patients with peripheral arterial disease (lower extremity, renal, mesenteric, and abdominal aortic): a collaborative report from the American Associations for Vascular Surgery/Society for Vascular Surgery, Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions, Society for Vascular Medicine and Biology, Society of Interventional Radiology, and the ACC/AHA Task Force on Practice Guidelines (writing committee to develop guidelines for the management of patients with peripheral arterial disease)--summary of recommendations. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2006;17(9):1383–97. doi: 10.1097/01.RVI.0000240426.53079.46. Epub 2006/09/23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Watson L, Ellis B, Leng GC. Exercise for intermittent claudication. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008;(4):CD000990. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD000990.pub2. Epub 2008/10/10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Murphy TP, Cutlip DE, Regensteiner JG, Mohler ER, Cohen DJ, Reynolds MR, et al. Supervised exercise versus primary stenting for claudication resulting from aortoiliac peripheral artery disease: six-month outcomes from the Claudication: Exercise Versus Endoluminal Revascularization (CLEVER) Study. Circulation. 2011 doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.075770. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.075770. Epub 2011/11/18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gardner AW, Parker DE, Montgomery PS, Scott KJ, Blevins SM. Efficacy of quantified home-based exercise and supervised exercise in patients with intermittent claudication: a randomized controlled trial. Circulation. 2011;123(5):491–8. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.963066. Epub 2011/01/26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Makris GC, Lattimer CR, Lavida A, Geroulakos G. Availability of Supervised Exercise Programs and the Role of Structured Home-based Exercise in Peripheral Arterial Disease. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2012 doi: 10.1016/j.ejvs.2012.09.009. Epub 2012/10/05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bartelink ML, Stoffers HE, Biesheuvel CJ, Hoes AW. Walking exercise in patients with intermittent claudication. Experience in routine clinical practice. Br J Gen Pract. 2004;54(500):196–200. Epub 2004/03/10. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Galea MN, Bray SR, Ginis KA. Barriers and facilitators for walking in individuals with intermittent claudication. Journal of Aging and Physical Activity. 2008;16(1):69–84. doi: 10.1123/japa.16.1.69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Garg PK, Liu K, Tian L, Guralnik JM, Ferrucci L, Criqui MH, et al. Physical activity during daily life and functional decline in peripheral arterial disease. Circulation. 2009;119(2):251–60. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.791491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Brawley LR, Rejeski WJ, King AC. Promoting physical activity for older adults: the challenges for changing behavior. Am J Prev Med. 2003;25(3 Suppl 2):172–83. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(03)00182-x. Epub 2003/10/14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Michie S, Ashford S, Sniehotta FF, Dombrowski SU, Bishop A, French DP. A refined taxonomy of behaviour change techniques to help people change their physical activity and healthy eating behaviours: the CALO-RE taxonomy. Psychol Health. 2011;26(11):1479–98. doi: 10.1080/08870446.2010.540664. Epub 2011/06/17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rollnick S, Miller WR. What is motivational interviewing? Behavioural and Cognitive Psychotherapy. 1995;23(4):325–34. doi: 10.1017/S1352465809005128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gollwitzer PM. Implementation intentions: Strong effects of simple plans. American Psychologist. 1999;54(7):493–503. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Degischer S, Labs KH, Aschwanden M, Tschoepl M, Jaeger KA. Reproducibility of constant-load treadmill testing with various treadmill protocols and predictability of treadmill test results in patients with intermittent claudication. J Vasc Surg. 2002;36(1):83–8. doi: 10.1067/mva.2002.123092. Epub 2002/07/04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Regensteiner JG, Steiner JF, Panzer RJ, Hiatt WR. Evaluation of Walking Impairment by Questionnaire in Patients with Peripheral Arterial-Disease. Clin Res. 1990;38(2):A515–A. [Google Scholar]

- 19.The Cochrane Collaboration [updated March 2011; cited 2012 15 January];The Cochrane Collaboration’s tool for assessing risk of bias. (5.1.0). 2011 Available from: http://www.cochrane.org/handbook/table-85a-cochrane-collaboration%E2%80%99s-tool-assessing-risk-bias.

- 20.Downs SH, Black N. The feasibility of creating a checklist for the assessment of the methodological quality both of randomised and non-randomised studies of health care interventions. J Epidemiol Community Health. 1998;52(6):377–84. doi: 10.1136/jech.52.6.377. Epub 1998/10/09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Deeks J, Dinnes J, D’Amico R, Sowden A, Sakarovitch C, Song F, et al. Evaluating non-randomised intervention studies. Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO; Colegate, Norwich: 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.van Tulder M, Furlan A, Bombardier C, Bouter L. Updated method guidelines for systematic reviews in the cochrane collaboration back review group. Spine. 2003;28(12):1290–9. doi: 10.1097/01.BRS.0000065484.95996.AF. Epub 2003/06/18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Collins TC, Lunos S, Carlson T, Henderson K, Lightbourne M, Nelson B, et al. Effects of a home-based walking intervention on mobility and quality of life in people with diabetes and peripheral arterial disease: a randomized controlled trial. Diabetes Care. 2011;34(10):2174–9. doi: 10.2337/dc10-2399. Epub 2011/08/30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cheetham DR, Burgess L, Ellis M, Williams A, Greenhalgh RM, Davies AH. Does supervised exercise offer adjuvant benefit over exercise advice alone for the treatment of intermittent claudication? A randomised trial. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2004;27(1):17–23. doi: 10.1016/j.ejvs.2003.09.012. Epub 2003/12/04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Christman SK. Intervention to slow progression of peripheral arterial disease [PhD Thesis] Ohio State University; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cunningham MA, Swanson V, O’Caroll RE, Holdsworth RJ. Randomized clinical trial of a brief psychological intervention to increase walking in patients with intermittent claudication. Br J Surg. 2012;99(1):49–56. doi: 10.1002/bjs.7714. Epub 2011/11/01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Quirk F, Dickinson C, Baune B, Leicht A, Golledge J. Pilot trial of motivational interviewing in patients with peripheral artery disease. Int Angiol. 2012;31(5):468–73. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Black N. Why we need observational studies to evaluate the effectiveness of health care. BMJ. 1996;312(7040):1215–8. doi: 10.1136/bmj.312.7040.1215. Epub 1996/05/11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kunz R, Oxman AD. The unpredictability paradox: review of empirical comparisons of randomised and non-randomised clinical trials. BMJ. 1998;317(7167):1185–90. doi: 10.1136/bmj.317.7167.1185. Epub 1998/10/31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Binnie A, Perkins J, Hands L. Exercise and nursing therapy for patients with intermittent claudication. J Clin Nurs. 1999;8(2):190–200. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2702.1999.00246.x. Epub 1999/07/13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Braun CM, Colucci AM, Patterson RB. Components of an optimal exercise program for the treatment of patients with claudication. J Vasc Nurs. 1999;17(2):32–6. doi: 10.1016/s1062-0303(99)90026-2. Epub 1999/12/22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fakhry F, Spronk S, de Ridder M, den Hoed PT, Hunink MG. Long-term effects of structured home-based exercise program on functional capacity and quality of life in patients with intermittent claudication. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2011;92(7):1066–73. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2011.02.007. Epub 2011/06/28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gartenmann L, Kirchberger I, Herzig M, Baumgartner I, Saner H, Mahler F, et al. Effects of exercise training program on functional capacity and quality of life in patients with peripheral arterial occlusive disease - Evaluation of a pilot project. VASA-J Vasc Dis. 2002;31(1):29–34. doi: 10.1024/0301-1526.31.1.29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jonason T, Ringqvist I, Oman-Rydberg A. Home-training of patients with intermittent claudication. Scand J Rehabil Med. 1981;13(4):137–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kruidenier LM, Nicolai SP, Hendriks EJ, Bollen EC, Prins MH, Teijink JAW. Supervised exercise therapy for intermittent claudication in daily practice. Journal of Vascular Surgery. 2009;49(2):363–70. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2008.09.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mouser MJ, Zlabek JA, Ford CL, Mathiason MA. Community trial of home-based exercise therapy for intermittent claudication. Vascular Medicine. 2009;14(2):103–7. doi: 10.1177/1358863X08098596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wullink M, Stoffers HE, Kuipers H. A primary care walking exercise program for patients with intermittent claudication. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2001;33(10):1629–34. doi: 10.1097/00005768-200110000-00003. Epub 2001/10/03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.MacAnaney O, Reilly H, O’Shea D, Egana M, Green S. Effect of type 2 diabetes on the dynamic response characteristics of leg vascular conductance during exercise. Diabetes & vascular disease research : official journal of the International Society of Diabetes and Vascular Disease. 2011;8(1):12–21. doi: 10.1177/1479164110389625. Epub 2011/01/26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Green S, Askew CD, Walker PJ. Effect of type 2 diabetes mellitus on exercise intolerance and the physiological responses to exercise in peripheral arterial disease. Diabetologia. 2007;50(4):859–66. doi: 10.1007/s00125-006-0587-7. Epub 2007/01/24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Fakhry F, van de Luijtgaarden KM, Bax L, den Hoed PT, Hunink MG, Rouwet EV, et al. Supervised walking therapy in patients with intermittent claudication. J Vasc Surg. 2012;56(4):1132–42. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2012.04.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gardner AW, Skinner JS, Cantwell BW, Smith LK. Progressive vs single-stage treadmill tests for evaluation of claudication. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1991;23(4):402–8. Epub 1991/04/01. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Heidrich H, Cachovan M, Creutzig A, Rieger H, Trampisch HJ. Guidelines for therapeutic studies in Fontaine's stages II-IV peripheral arterial occlusive disease. Vasa. 1995;24(2):107–19. German Society of Angiology . Epub 1995/01/01. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.