Abstract

Background:

Ki-67 which is a non-histone nuclear protein which is expressed in proliferating cells, during all the active phases of the cell cycle. Increased Ki-67 expression has been seen in several inflammatory and malignant conditions like diabetes, rheumatoid arthritis, atherosclerosis, pancreatitis and squamous cell carcinoma.

Aim:

The aim of the present study is to analyze the expression of Ki-67 in gingival tissues by immunohistochemistry in smokers and non-smokers with healthy gingiva and chronic periodontitis.

Materials and Methods:

Gingival biopsies (n = 32) were obtained from smokers who had clinically healthy gingiva (n = 8), smokers with periodontitis (n = 8), chronic periodontitis (n = 8) and healthy gingiva (n = 8). The expression of Ki-67 was evaluated immunohistochemically. Statistical analysis used: Mean and standard deviation were estimated for the gingival tissue extract sample for each study group. Mean values were compared between different study groups by, one way ANOVA, post hoc analysis. In this study P < 0.05 was considered as the level of significance.

Results:

The mean number of Ki-67 positive cells/field was higher in the smokers with periodontitis group. When the mean Ki-67 positive cells were compared between different groups, statistical significant difference was observed between healthy and both the periodontitis groups (P = 0.000) and between smokers group (P = 0.001).

Conclusions:

Ki-67 was maximally expressed in smoker with periodontitis followed by chronic periodontitis patients, healthy smokers and healthy control patients which shed light on the toxic effects of tobacco in dysregulating the cell cycle and cellular proliferation. The findings of this study also help us to understand the role of the cell cycle in resolution of periodontal inflammation which is a salient feature in the pathogenesis of chronic periodontitis.

Keywords: Chronic periodontitis, Ki-67, smoking

INTRODUCTION

Chronic periodontitis is an inflammatory disease of specific microbial etiology that affects and destroys the dental attachment apparatus. One of the salient features of chronic periodontitis is the fact that there are periods of remission and exacerbation. During remission though complete self resolution of chronic periodontal disease does not occur; there is some amount of repair and the body attempts to heal the diseased periodontium. In this regard, the role of cellular proliferation to attempt repair should be understood.

Moreover, periodontal disease is multifactorial. One of the most well recognized risk factor is tobacco smoking whose association has been proven by several land mark epidemiological studies.[1] The numerous deleterious components like nicotine, benzene, benzo-pyrene, acrolein and tar contained in tobacco smoke cause oxidative burden and stimulate hyper inflammatory state. They can also distinctly affect cell proliferation and critical events in the cell cycle.

When we analyze cell proliferation in healthy and diseased tissues, one of the best markers that can be used is Ki-67, which is a non-histone nuclear protein and is expressed in proliferating cells, during all the active phases of the cell cycle. Increased Ki-67 has been seen in several inflammatory and malignant conditions like diabetes,[2] rheumatoid arthritis,[3] atherosclerosis,[4] pancreatitis,[5] and squamous cell carcinoma.[6] Since chronic periodontitis is also an inflammatory condition, we set out to measure Ki-67 by immunohistochemistry in healthy and diseased periodontium of smokers and non-smokers.

The aim of the present study is to analyze the expression of Ki-67 in gingival tissues by immunohistochemistry in healthy, chronic periodontitis, smokers with and without periodontits. Therefore objectives of present study are: (1) to analyze if there is a difference in Ki-67 expression in smokers and non-smokers with healthy gingiva and chronic periodontitis. (2) to understand the role of Ki-67 in the pathogenesis of periodontal disease.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

A total of 32 patients attending the outpatient clinic of department of periodontics, at Sri Ramachandra dental college, were recruited for this study after obtaining their informed consent. The subjects recruited for the study were divided into four groups. Group I (control) includes eight healthy subjects, group II includes eight non-smokers with chronic periodontitis, group III includes eight smokers without chronic periodontitis and group IV includes eight smokers with chronic periodontitis.

Inclusion criteria

Healthy group – patients should have clinically healthy gingiva, no bleeding on probing, no attachment loss, probing depth ≤3 mm, no habit of smoking and no radiographic evidence of bone loss

Chronic periodontitis group – patients should have at least ten teeth present, bleeding on probing, no history of smoking, probing depth of 5 mm and loss of attachment ≥2 mm and with radiographic evidence of more than 3 mm bone loss

Smokers without chronic periodontitis – chronic smokers with minimum duration of 3 years, patients with clinically healthy gingival as defined by the previously mentioned criteria and no attachment loss

Smokers with periodontitis – chronic smokers with minimum duration of 3 years, patients should have at least 10 teeth present, probing depth of 5 mm and loss of attachment ≥2 mm and with radiographic evidence of more than 3 mm bone loss.

Exclusion criteria

Patients with history of any systemic diseases, such as diabetes, hypertension etc., patient under any antibiotics or anti-inflammatory drugs in the past 6 months duration, patients who underwent any periodontal therapy in the past 6 months, and pregnant or lactating women.

Measurements of clinical parameters OHI-S (Green and Vermillion), probing depth and clinical attachment levels were measured.

Sample collection and processing

Control gingival samples were obtained from systemically healthy patients undergoing orthodontic extractions. Chronic periodontitis samples were obtained from patients undergoing periodontal treatment in the department of periodontics.

The portion of the papilla was excised using surgical blade and were washed in sterile saline to remove blood and fixed in 10% buffered formalin solution for 24 h. Following fixation, the samples were dehydrated in alcohol (100%) and embedded in paraffin and the blocks were prepared. Then two sections 5 μm thickness were made, one section for H and E staining and other for immunohistochemistry.

Methodology

Streptavidin − biotin method was used for detection of Ki-67. After deparaffinization by xylene and rehydration in 96% ethanol, endogenous peroxide activity was blocked with 3% hydrogen peroxide in tris buffered saline (TBS pH 7.6) for 10 min and then rinsed with TBS. For antigen retrieval, the sections were boiled in citrate buffer for 15 min and left to cool at room temperature. After washing with TBS, sections were incubated for 5 min to block non-specific back ground staining. Primary antibodies to anti Ki-67 were added and the samples were incubated for 2 h at room temperature. After rinsing thoroughly with TBS, the slides were overlaid with secondary antibody for 10 min. The immunoperoxidase labeling was performed using streptavidin peroxidase for 10 min. Then aminoethylcarbazole was used as a chromogen for visualization of antibody binding. Finally, the sections were counterstained with Mayer's hematoxylin, cleared, and mounted for examination.

Statistical analysis used

Mean and standard deviations were estimated for the gingival tissue extract sample for each study group. Mean values were compared between different study groups by, one way ANOVA, post hoc analysis. In this study P < 0.05 was considered as the level of significance.

RESULTS

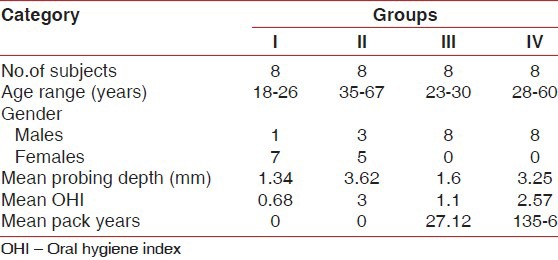

Demographic variables, mean values of clinical measurements, and the mean pack year in smokers are outlined in Table 1.

Table 1.

Comparison of demographic variables between the groups

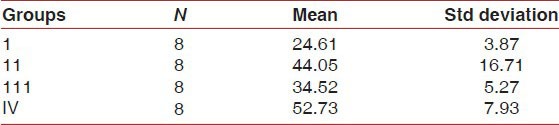

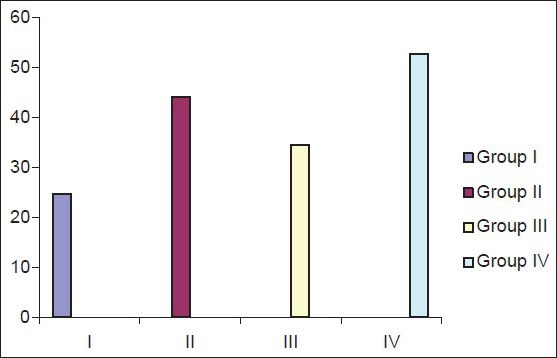

The mean Ki-67 positive cells/field were shown in Table 2 which was highest in group IV, i.e. smoker with periodontitis (52.73 cells/field) followed by chronic periodontitis (44.05 cells/field), smoker without periodontitis (34.52 cells/field) and healthy control (24.61 cells/field).

Table 2.

Mean number of Ki-67positive cells/field

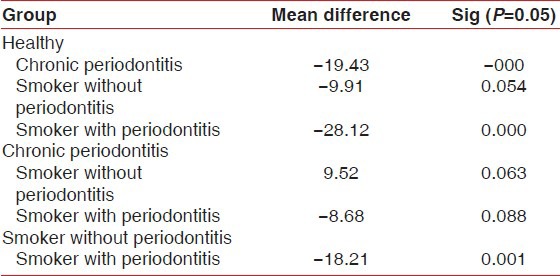

The mean Ki-67 positive cells/field was being compared between groups in Table 3.

Table 3.

Comparison of mean Ki-67 levels in different groups

Comparison between healthy and chronic periodontitis (−19.43), smoker with periodontitis (−28.12) was statistically significant (P = 0.000).

Whereas between healthy and smoker without periodontitis (−9.91) was statistically not significant (P = 0.054).

Comparison between chronic periodontitis and smoker without periodontitis (9.52), smoker with periodontitis (−8.68) was statistically not significant (P = 0.063, 0.088).

Comparison between smoker without periodontitis and smoker with periodontitis (−18.21) was statistically significant (P = 0.001).

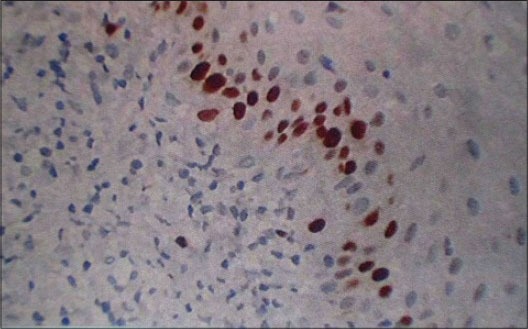

Immunohistochemistry of gingival tissue samples revealed positivity for Ki-67 in healthy, chronic periodontitis, smokers, and smokers with periodontitis.

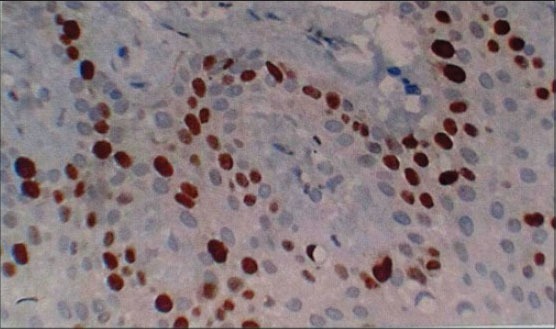

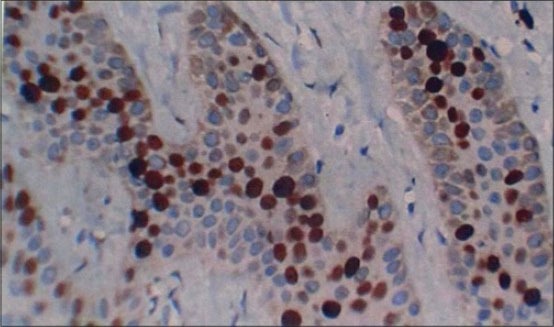

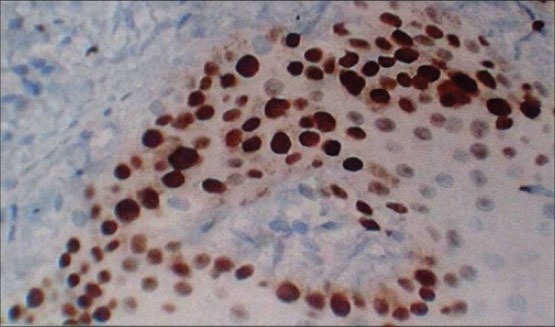

In healthy [Figure 1] Ki-67 positive cells were seen in the basal layer of the epithelium. The hematoxylin − eosin stained slides showed normal parakeratinized stratified squamous epithelium. The underlying connective tissue showed collagen fibers and blood vessels. In chronic periodontitis [Figure 2] Ki-67 positive cells were seen in the basal and parabasal layer of the epithelium. The hematoxylin − eosin stained slides showed parakeratinized proliferative epithelium. The underlying connective tissue showed intense chronic inflammatory cell infiltration predominantly lymphocytes, plasma cells, and dilated blood capillaries. In smokers without periodontitis [Figure 3] Ki-67 positive cells were seen in the basal layer of the epithelium. The hematoxylin − eosin stained slides showed orthokeratotic stratified squamous epithelium with features of basal cell hyperplasia and increased melanin pigmentation. The underlying connective tissue showed collagen fibers, dilated blood capillaries and few inflammatory cells. In smokers with periodontitis [Figure 4] Ki-67 positive cells were seen in the basal and parabasal layer of the epithelium. The hematoxylin − eosin stained slides showed parakeratotic proliferative stratified squamous epithelium with features of basal cell hyperplasia and acanthosis. The underlying connective tissue showed dense inflammatory cells predominantly lymphocytes, plasma cells, and dilated blood capillaries.

Figure 1.

Section of gingiva showing Ki-67 positive cells at ×40 in different groups: Healthy control

Figure 2.

Section of gingiva showing Ki-67 positive cells at ×40 in different groups: Chronic periodontitis

Figure 3.

Section of gingiva showing Ki-67 positive cells at ×40 in different groups: Smokers without periodontitis

Figure 4.

Section of gingiva showing Ki-67 positive cells at ×40 in different groups: Smokers with periodontitis

DISCUSSION

The gingiva is a tissue that is a part of the oral mucosa that protects the alveolar part of the periodontium by forming a soft tissue casing. The gingival tissues have a good repair potential and regenerative capacity as suggested by the studies of Narayanan et al.[7] Healing and repair of the diseased periodontium is characterized by cell proliferation, mitosis, and differentiation. With regard to assessing the proliferative rate of cells, Ki-67 is one of the best markers available. The purpose of our study was to immunolocalize Ki-67 in gingival tissue samples obtained from healthy individuals and chronic periodontitis patients (smokers and non-smokers). The reason for recruiting smokers into the study was to analyze if cell proliferation and periodontal repair in this group is affected by tobacco smoking. The results of our study showed that all samples of gingival tissues expressed Ki-67 antigen in the basal and parabasal layer of the epithelium. But the lowest expression was seen in healthy (24.61cells/field) followed by smokers without periodontitis (34.52), chronic periodontitis (44.05), and smoker with periodontitis (52.73). The Ki-67 expression intensity was lowest in healthy individuals. This could be due to the fact that healthy gingival is a somatic tissue with a normal turnover rate as compared to the other tissues of the body. Teresa et al., have shown that normal Ki-67 expression in health is significantly lower compared to inflammation or cancerous state.[8]

The Ki-67 expression was higher in healthy smokers compared to the healthy control group. This finding can be explained by the fact that tobacco products have a significant effect on cell proliferation. Arredondo et al. have shown that nicotine can induce oral keratinocyte proliferation.[9] Another important study by Van Oijen et al. suggests that proliferative index as shown by Ki-67 expression is higher in smokers compared to non-smokers due to local regenerative response of the tissues to compensate for increased cell loss or damage by tobacco.[10]

With regard to chronic periodontitis group, Ki-67 expression was higher than the previous two groups discussed. The reason for elevated Ki-67 levels in this group is due to effects of inflammation. Elevated NF-κb levels have been shown in inflamed periodontal tissues by the study of Ambili et al.[11] Also another study by Doger et al. in psoriatic dermatitis cases has shown a positive correlation between NF-κb, Ki-67 and dermal cell turnover rate.[12] May be the same mechanism of NF-κb mediated Ki-67 expression could operate in the periodontitis samples compared to healthy patients.

On one hand, proinflammatory cytokines and mediators such as PGE2 are involved in periodontal tissue destruction but on the other hand elevated growth factor levels have also been seen in inflamed periodontal tissues compared to healthy tissues. In this regard Gurkan et al. have shown that TGF-β levels have been found to be extensively elevated in chronic periodontitis.[13] TGF β can distinctly increase Ki-67 levels as suggested by the study of Piekarska et al.[14] Similarly, HGF has also been shown to increase in chronic periodontitis.[15] HGF can also modulate Ki-67 expression and the cell cycle as suggested by the study of Kanayama et al.[16] Another important growth factor involved in periodontal repair and wound healing is PDGF. This molecule has mitogenic effects on various cell types in the body. A study by Rollman et al. has shown that PDGF gene transfer has a mitogenic effect on keratinocytes as seen by increased Ki-67 expression.[17] With regard to periodontal diseases an immunohistochemical study by Pinheiro et al. has shown increased PDGF expression in inflamed gingiva rather than healthy gingiva.[18] This study gives an evidence of how locally generated PDGF in chronic periodontitis could modulate Ki-67 upregulation.

Another important chemical mediator of inflammation is nitric oxide. Vascular effects of nitric oxide and its influence on the progression of inflammation has been well understood. Batista et al. have shown increased levels of nitric oxide in periodontitis tissues compared to healthy gingiva.[19] In this connection another study by Hussain et al. has revealed that elevated nitric oxide levels in inflamed sites regulates accelerated cell proliferation and tumorigenesis.[20] Combining the results of the above two studies we can understand that nitric oxide is an important upregulator of Ki-67 in chronic periodontitis samples.

The Ki-67 expression is highest in smoker with periodontitis compared to the other three groups [Figure 5]. This is due to two reasons i. e., nicotinic effect and inflammation. Even though the clinical appearance of chronic periodontitis in a smoker is devoid of all the cardinal signs of inflammation, such as altered color, consistency and bleeding on probing, there is a higher amount of destruction in smokers with chronic periodontitis due to dysregulation of cytokines such as IL-β and TNF-α. Several studies have shown that tobacco smoke contains abundant amount of free radicals and can cause distinct oxidative stress.[21,22] Oxidative injury due to locally generated ROS can deplete intracellular thiol compounds thereby switching on the NF-b and AP-1 signaling pathways which are highly redox sensitive. As mentioned earlier elevated NF-b can further upregulate the Ki-67 levels and accelerate cell proliferation. Moreover, as earlier mentioned the nicotinic effects of tobacco smoke on the neurotransmitter acetylcholine and thereby on activation of cell proliferation should be re-emphasized here. Hence, the highest value of Ki-67 in this group should be attributed to the super added effect of smoking and inflammation on the tissues.

Figure 5.

Mean number of Ki-67 positive cells/field

The limitations of our study include the fact that we have not recruited any female subjects in the smoking group. This has occurred due to the clinical settings in our country where females do not have tobacco smoking habit. However, our study results shed light on the role of the cell proliferation marker Ki-67 in the pathogenesis of periodontal disease.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Albandar JM, Streckfus CF, Adesanya MR, Winn DM. Cigar pipe and cigarette smoking as risk factor for periodontal disease and tooth loss. J Periodontol. 2000;71:1874–81. doi: 10.1902/jop.2000.71.12.1874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vairaktaris E, Spyridonidou S, Goutzanis L, Vylliotis A, Lazaris A, Donta I, et al. Diabetes and oral oncogenesis. Anticancer Res. 2007;27:4185–93. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pessler F, Dai L, Diaz-Torne C, Ogdie A, Gomez-Vaquero C, Paessler ME, et al. Increased angiogenesis and cellular proliferation as hallmarks of the synovium in chronic septic arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;59:1137–46. doi: 10.1002/art.23915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hermanova M, Nenutil R, Kren L, Feit J, Pavlovsky Z, Dite P. Proliferative activity in pancreatic intraepithelial neoplasias of chronic pancreatitis resection specimens; detection of a high risk lesion. Neoplasma. 2004;51:400–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tricot O, Mallat Z, Heymes C, Belmin J, Leseche G, Tedgui A. Relation between endothelial cell apoptosis and blood flow direction in human atherosclerotic plaques. Circulation. 2000;101:2450–3. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.101.21.2450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tumuluri V, Thomas GA, Fraser IS. The relationship of proliferating cell density at the invasive tumour front with prognostic and risk factors in human oral squamous cell carcinoma. J Oral Pathol Med. 2004;33:204–8. doi: 10.1111/j.0904-2512.2004.00178.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Narayanan AS, Bartold PM. Biochemistry of periodontal connective tissues and their regeneration. A current perspective. Connect Tissue Res. 1996;34:191–201. doi: 10.3109/03008209609000698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Teresa DB, Neves KA, Neto CB, Fregonezi PA, de Oliveira MR, Zuanon JA, et al. Computer assisted analysis of cell proliferation markers in oral lesions. Acta Histochem. 2007;109:377–87. doi: 10.1016/j.acthis.2007.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Arredondo J, Nguyen VT, Chernyavsky AI, Jolkovsky DL, Pinkerton KE, Grando SA. A receptor mediated mechanism of nicotine toxicity in oral keratinocytes. Lab Invest. 2001;81:1652–68. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.3780379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Van Oijen MG, Gilsing MM, Rijksen G, Hordijk GJ, Slootweg PJ. Increased number of proliferating cells in oral epithelium from smokers and ex-smokers. Oral Oncol. 1998;34:297–303. doi: 10.1016/s1368-8375(98)00007-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ambili R, Santhi WS, Janam P, Nandakumar K, Pillai MR. Expression of activated transcription factor NF-κB in periodontally diseased tissues. J Periodontol. 2005;76:1148–53. doi: 10.1902/jop.2005.76.7.1148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Doger FK, Dikicioglu E, Ergin F, Unal E, Sendur N, Uslu M. Nature of cell kinetics in psoriatic epidermis. J Cutan Pathol. 2007;34:257–63. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0560.2006.00719.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gurkan A, Emingil G, Cinarcik S, Berdeli A. Gingival crevicular fluid transforming growth factor β1 in several forms of periodontal disease. Arch Oral Biol. 2006;51:906–12. doi: 10.1016/j.archoralbio.2006.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Piekarska A, Piekarski J, Omulecka A, Szymczak W, Kubiak R. Expression of Ki-67, TGF-β1 and B-cell lymphoma-leukemia-2 in liver tissue of patients with chronic liver diseases. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2006;21:700–10. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2006.04149.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nagaraja C, Pradeep AR. Hepatocyte growth factor levels in gingival crevicular fluid in health disease and after treatment. J Periodontol. 2007;78:742–7. doi: 10.1902/jop.2007.060249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kanayama M, Takahara T, Yata Y, Xue F, Shinno E, Nonome K, et al. Hepatocyte growth factor promotes colonic epithelial regeneration via Akt signaling. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2007;293:G230–9. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00068.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rollman O, Jensen UB, Ostman A, Bolund L, Gustafsdottir SM, Jensen TG. PDGF responsive epidermis formed from human keratinocytes transduced with the PDGF beta receptor gene. J Invest Dermatol. 2003;120:742–9. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1747.2003.12129.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pinheiro ML, Feres-Filho EJ, Graves DT, Takiya CM, Elsas MI, Elsas PP, et al. Quantification and localization of PDGF in gingival of periodontitis patients. J Periodontol. 2003;74:323–8. doi: 10.1902/jop.2003.74.3.323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Batista AC, Silva TA, Chun JH, Lara VS. Nitric oxide synthesis and severity of human periodontal disease. Oral Dis. 2002;8:254–60. doi: 10.1034/j.1601-0825.2002.02852.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hussain SP, He P, Subleski J, Hofseth LJ, Trivers GE, Mechanic L, et al. Nitric oxide is a key component in inflammation-accelerated tumorigenesis. Cancer Res. 2008;68:7130–6. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-0410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pryor WA, Church DF, Evans MD, Rice WY, Hayes JR. A comparison of free radical chemistry of tobacco-burning cigarettes and cigarettes that only heat tobacco. Free Radic Biol Med. 1990;8:275–9. doi: 10.1016/0891-5849(90)90075-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vassalle C, Maffei S, Ndreu R, Mercuri A. Age-related oxidative stress modulation by smoking habit and obesity. Clin Biochem. 2009;42:739–41. doi: 10.1016/j.clinbiochem.2008.11.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]