Abstract

Aim:

The purpose of the study was to evaluate the serum levels of zinc (Zn) and magnesium (Mg) in type 2 diabetes mellitus (DM) with periodontitis patients and to correlate them with the levels of serum cholesterol, high density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-c), low density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-c), and triglycerides among the study subjects.

Materials and Methods:

A total of 600 subjects participated in the study, who were divided into four groups as control healthy individuals (group I), type 2 DM without periodontitis (group II), type 2 DM with periodontitis (group III), and periodontitis subjects without DM (group IV), matched for age, sex, and duration of diabetes. Serum concentrations of glucose, total cholesterol, triglycerides, HDL-c, Zn, and Mg were measured using enzymatic methods in an UV absorption spectrophotometer, and LDL-c was calculated using Friedwald's formula. Student's t-test, Pearson correlations, and analysis of variance (ANOVA) tests were used for statistical analysis.

Results:

The serum zinc level was found to be significantly increased in type 2 DM without periodontitis (group II) and periodontitis subjects without type 2 DM (group IV) (P < 0.0001), and the level was lowered in type 2 DM with periodontitis (group III) when compared to control. The serum Mg level was found to be significantly decreased (P < 0.0001) in group II, group III, and in group IV, when compared to control. We found a significant increased level of serum total cholesterol and LDL-c and decreased triglycerides and HDL-c in type 2 DM subjects with periodontitis (group III, P < 0.0001).

Conclusion:

Patients with DM and periodontitis had altered metabolism of Zn and Mg which were linked to increased values of serum cholesterol and LDL-c and decreased HDL-c, contributing to the progression and complications of type 2 DM with periodontitis.

Keywords: Cholesterol, magnesium, periodontitis, type 2 diabetes mellitus, zinc

INTRODUCTION

Periodontitis is a multifactorial disease caused by gram-negative anaerobic bacteria, along with systemic and environmental factors. Periodontitis, if untreated, leads to loss of alveolar bone and supporting tissues of the teeth, and hence, a proper intervention is required from stage to stage in order to retain the teeth in the oral cavity in a functional state as long as possible. Many researchers found that patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus (DM) are at a higher risk for periodontitis.[1,2,3] It is, therefore, important to screen patients for diabetes with periodontitis that may threaten longevity and the quality of life. Systemic risk factors like DM influence the progression of periodontitis, which is attributed to the variation and concentration of plasma micronutrients.

Zinc (Zn) is an essential trace element which is involved in a multitude of intracellular processes of more than 300 different enzymes, acting as an essential requirement for the successful growth of many internal organs, stabilizing cell membranes, and modulating membrane-bound enzymes and insulin action.[4,5,6] Sprren Kiilerich et al.[7] observed that Zn absorption decreases in diabetes, thereby leading to its intracellular depletion. The liver is a target organ of Zn, and the metal taken up by the liver cells is stored by binding to the cytosolic proteins. Zn also accumulates in the mitochondria and markedly increases succinate dehydrogenase activity in that organelle. It is uncertain, however, whether Zn taken up by the liver binds to the subcellular organelles and affects the cellular metabolic systems. Alena et al.[8] recently reported that the altered metabolism of Zn would lead to some diabetic complications. Their results showed that patients with type 2 DM had lesser amounts of serum Zn and Mg when compared to healthy subjects. Epidemiologic studies have shown a high prevalence of hypomagnesemia in type 2 diabetic subjects with poor glycemic control.

Magnesium (Mg) acts as a critical cofactor involved in the carbohydrate, lipid, and protein metabolism. In all, Mg2+ activates over 300 cellular enzymes and is important for the synthesis of proton and electron transporters in the energy cycle of the cell. Mg is also an integral part of the structure of cellular and subcellular membranes where its major function is providing membrane stability.[9,10] Individuals with DM have lower serum Mg levels than those without DM. Insulin is a major hormone involved in the regulation of Mg metabolism. Mg is necessary for the synthesis of compounds with energy-rich bonds of any type, and the reconstitution of these compounds from the products of their own degradation is accomplished by phosphorylation coupled to oxidation/reduction reaction.[11,12]

Epidemiologic studies have shown a high prevalence of hypomagnesemia in type 2 diabetic subjects with poor glycemic control. It has recently been shown that increased Mg intake may be associated with reduced risk of developing the metabolic syndrome.[13] The favorable effect of increased Mg intake on DM and DM risk has been attributed to an effect of magnesium on insulin sensitivity.[14] Studies on patients with metabolic syndrome or diabetes have shown that individuals with low levels of Mg have lower levels of high density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-c), but higher levels of triglycerides and total cholesterol.[15] Serum Mg levels have shown a negative correlation with HDL-c, but a positive correlation with triglycerides and total cholesterol when hemodialysis patients and the general population were studied.[16]

In the light of these findings, considering that relations between blood glucose, serum Zn, Mg, and lipid profiles may have a role in the interaction between diabetes and periodontitis, we aimed to compare the serum Zn, Mg, and lipid levels and investigate the relations of these parameters with periodontal status in type 2 DM patients with periodontitis and in patients who are systemically healthy with periodontitis, in order to gain insight into the potential pathophysiological processes that may contribute to the development of type 2 DM and periodontitis.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study population

A total of 600 subjects were included in the study. The subjects were divided into four groups consisting of 150 participants in each group as follows: Control healthy individuals (group I), type 2 DM without periodontitis (group II), type 2 DM with periodontitis (group III), and periodontitis without type 2 DM (group IV). Their ages ranged from 25 to 55 years. Group II patients were enrolled from a SRM speciality hospital in Chennai, India, and group III and group IV patients were selected from the outpatients attending the Department of Periodontology and Oral Implantology, SRM Dental College, Ramapuram, India.

The study included both male and female type 2 DM patients with and without periodontitis. Smokers, alcoholics, drug abusers, and patients under antibiotics and having systemic diseases other than diabetes were excluded from the study. Among the non-diabetic control group, those with high blood pressure, patients who have had periodontal therapy 6 months prior to the study, patients taking hormone drugs or lipid-lowering drugs or oral contraceptives, and pregnant women were excluded. The healthy controls were not on any kind of prescribed medication or dietary restrictions. A standard questionnaire and physical examination were used to assess the age, gender, blood pressure, body mass index (BMI), and duration of diabetes. Institutional ethical committee approval was obtained from Medical and Health Sciences, and an informed consent was taken from all subjects prior to the study.

Evaluation of periodontal status

Probing pocket depth and clinical attachment loss were used to assess the periodontal conditions of the diabetic and non-diabetic patients with periodontitis. Mean probing depth of ≥5 mm and clinical attachment loss of ≥3 mm in at least 40% of teeth were considered to be included in the periodontitis group. The control subjects chosen had healthy gingiva with no irrefutable attachment loss and a probing pocket depth of ≤3 mm. The periodontal grade was determined by a trained periodontist of the Department of Periodontology, SRM Dental College, Ramapuram, Chennai [Figure 1].

Figure 1.

Probing pocket depth

Sample collection

Blood samples were collected after an overnight fast and centrifuged at 1500 rpm for 10 min. The serum obtained was used for the estimation of glucose total cholesterol, triglycerides, HDL-c, low density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-c), Zn, and Mg.

Methodology

Serum glucose, total cholesterol, HDL-c, triglycerides, zinc, and magnesium were estimated in a digital UV spectrophotometer (SL-159 ELICO) using enzymatic kits. Serum glucose was measured by glucose oxidase-peroxidase (GOD-POD) method using the reagent kit purchased from Merck Specialities Private Limited, Mumbai India. Total cholesterol and HDL-c were estimated with cholesterol oxidase-phenol 4-aminoantipyrine peroxidase (CHOD-PAP) purchased from Span Diagnostics Limited, Surat, India. LDL-c was calculated using Friedwald's formula.[17] Serum triglyceride level was evaluated by means of glycerokinase-peroxidase (GPO) method using the reagent kits obtained from Reckon Diagnostics Private Limited, Baroda, India. Serum zinc level was estimated using pyridylazo-N-propyl-N-sulfopropylamino-phenol (nitro-PAPS) method with the kit purchased from Crest Biosystems, Goa, India, and serum magnesium concentration was measured with xylidyl blue dye reagent kit purchased from Agappe Diagnostics, Kerala, India.

Statistical analysis

Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD). Comparisons between the groups were made using analysis of variance (ANOVA). Correlations between various variables were done using Pearson's correlation equations. A probability value (P value) less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Data were analyzed using the Graph Pad Prism 6 for Windows statistical software package (San Diego, CA, USA).

RESULTS

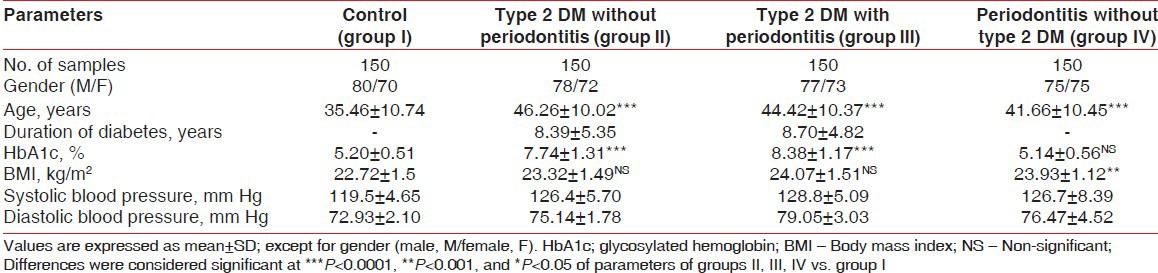

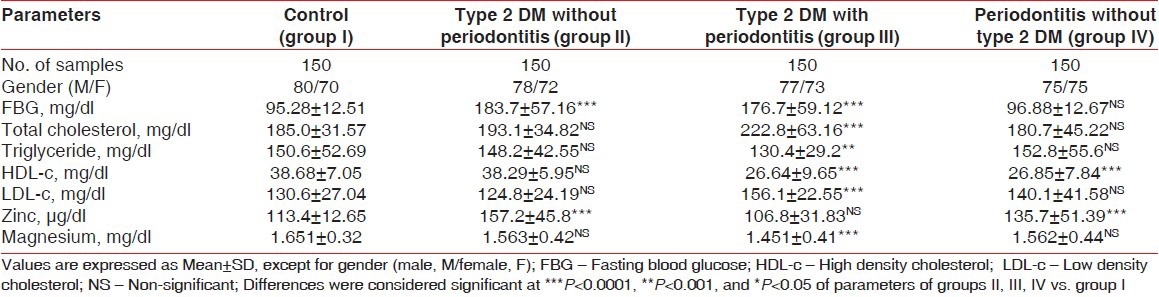

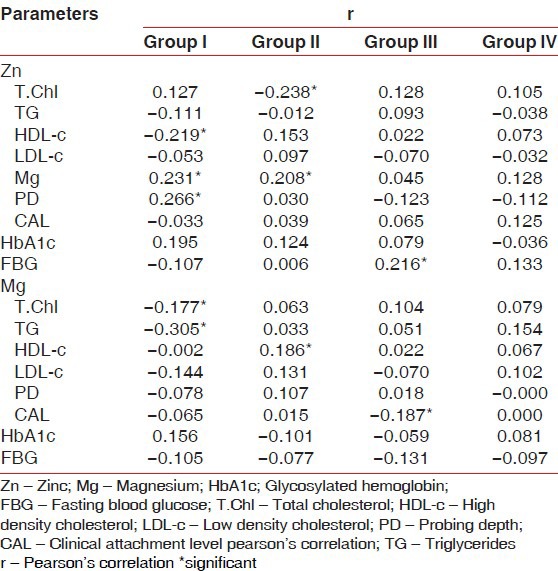

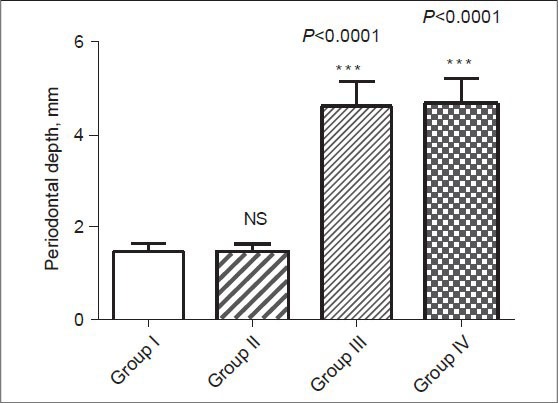

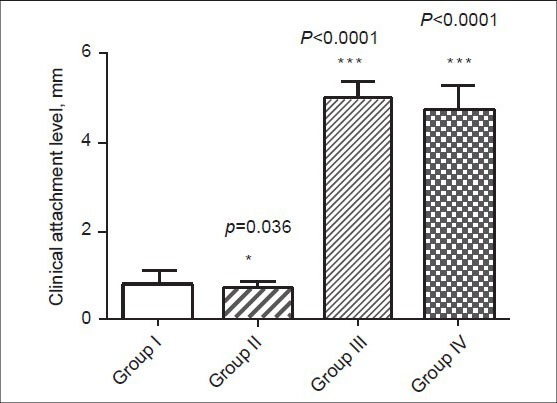

The demographic data and clinical characteristics of the study population in the control (group I), type 2 DM without periodontitis (group II), type 2 DM with periodontitis (group III), and periodontitis without type 2 DM (group IV) are shown in Tables 1 and 2, respectively. Pearson correlation data analysis is given in Table 3. The mean probing depth and clinical attachment level of periodontitis subjects with and without diabetes are presented in Figures 2 and 3, respectively.

Table 1.

Demographic data of the study population

Table 2.

Clinical characteristics of the study population

Table 3.

Pearson correlation between serum zinc and magnesium levels with all the experimental data included in the study

Figure 2.

Mean probing pocket depth in healthy control (group I), type 2 DM without periodontitis (group II), type 2 DM with periodontitis (group III), and periodontitis without type 2 DM (group IV) subjects

Figure 3.

Mean clinical attachment level in healthy control (group I), type 2 DM without periodontitis (group II), type 2 DM with periodontitis (group III), and periodontitis without type 2 DM (group IV) subjects

The mean hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) levels were found to be elevated in group II and group III subjects. Type 2 DM with periodontitis (group III) patients had a higher mean BMI than those of group I, group II, and group IV subjects. Group III subjects also exhibited higher levels of systolic blood pressure and diastolic blood pressure [Table 1]. The levels of total cholesterol, fasting blood glucose, and LDL-c were elevated and the levels of triglycerides, HDL-c, Zn, and Mg were found to be significantly lowered in type 2 DM with periodontitis (group III) patients when compared to the subjects in the other groups, [Table 2].

The association between serum zinc and magnesium levels with the experimental parameters was evaluated by Pearson correlation analysis. We observed a significant positive correlation of serum Zn with Mg (r = 0.231, P = 0.020) and probing depth (r = 0.266, P = 0.007) and significant negative correlation with HDL-c (r = −0.219, P = 0.028) in group I subjects. For type 2 diabetes patients without periodontitis, Zn correlated positively with Mg (r = 0.208, P = 0.036) and negatively with total cholesterol (r = −0.238, P = 0.017). However, in the control group, Mg correlated positively with HbA1c and negatively with total cholesterol and triglycerides. Also, Mg correlated positively with HDL-c (r = 0.186, P = 0.062) in patients having type 2 DM without periodontitis. Moreover, in group III patients, Mg correlated positively with fasting serum glucose (r = 0.216, P = 0.030) and negatively with the clinical attachment level (r = −0.187, P = 0.061) [Table 3].

DISCUSSION

Type 2 DM with periodontitis can alter serum Zn, Mg, and lipid profile status. Perturbations in Zn and Mg metabolism are more pronounced in periodontitis subjects with DM. Zn metabolism is linked to periodontitis; in periodontitis patients, it is inversely related to triglycerides and Mg, whereas in type 2 DM with periodontitis, it is inversely related to serum glucose, triglycerides, and HDL-c and protects against hyperglycemia and insulin resistance.[18] A direct role of Zn as a prostatic antibacterial factor has been postulated due to its bactericidal activity against a variety of gram-positive and gram-negative bacteria. Increased values observed in total cholesterol, triglycerides, LDL-c, and Zn were related to increased values of metabolic risk factors like blood pressure, serum lipids, and hyperglycemia.

An excess of free Zn ions could lead to oxidative damage in the mitochondria, which could be an explanation for the early disruption of mitochondrial potential and for the decrease in the anti-apoptotic membrane-bound protein, located predominantly in the mitochondria and endoplasmic reticulum, which promotes cell survival by inhibiting the adapters needed for the activation of proteases that dismantle the cell. High Zn concentrations are responsible for induction of apoptosis in cells with deficiencies in uptake and complexing. Though Zn is generally considered to be protective with its antioxidant property, the study conducted by Hiroko Matsui et al.[19] revealed the toxic effect of Zn even in micromolar range under oxidative stress induced by H2 O2. It is likely that Zn is involved in the cell death acutely induced by H2 O2.

There are two possible mechanisms for the H2 O2 induced increase in intracellular Zn2+ concentration. They are: (1) H2 O2 may increase intracellular Zn2+ concentration by inducing Zn2+ release from intracellular stores. Zn2+ makes a complex with the thiol groups of protein and nonprotein. The modification from thiol to disulfide releases Zn2+ from the protein and nonprotein. (2) H2 O2 may increase intracellular Zn2+ concentration by increasing membrane Zn2+ permeability. Zn protects biological structures from oxidative stress by maintaining the levels of glutathione and metallothionein, interacting with other transient metal ions that promote the formation of hydroxyl radical, and so on. Furthermore, zinc irreversibly damages the major enzymes of energy production, prior to Zn-dependent multi-conductance channel activity in mitochondria. In addition, an excessive increase in intracellular Zn concentration may change intracellular oxidative state. The ability of Zn to retard oxidative processes has been recognized for many years. Zn may protect the cells against oxidative stress which exerts cytotoxic action by increasing intracellular Zn concentration. Therefore, it is concluded that Zn exerts reciprocal actions that are dependent on the oxidative stress.

According to Walter et al.,[20] diabetes patients commonly have depletion of Mg, probably due to its urinary losses that accompany glycosuria. It is a renowned truth that hypomagnesemia is prevalent among the diabetes patients without periodontitis, but the findings of our results revealed that the concentration of Mg was decreased slightly and was non-significant in the case of type 2 diabetes without periodontitis (group II) and non-diabetic periodontitis (group IV) patients, while the level of magnesium was observed to be decreased significantly (P < 0.0001) in patients of type 2 diabetes with periodontitis (group III) when compared to control group. As the disease progresses with periodontitis, the Mg level was found to be decreased more significantly, indicating that the diabetic patients who develop periodontitis are more prone to diabetic complications. In addition, we also observed that hypomagnesemia is linked significantly to increased serum cholesterol and LDL-c and decreased serum HDL-c and triglyceride concentrations among the patients of type 2 DM with periodontitis.

Zn plays a key pathophysiological role in major neurological disorders as well as diabetes, while being essential for the activity of numerous Zn-binding proteins. Zn also plays a highly complex role in the physiology of the islets of Langerhans. Stimulation of lipogenesis in the adipocyte describes the synergism between insulin and Zn. Administration of low doses of Zn has been shown to protect against the onset of diabetes in an animal model of the disease. Furthermore, it has been shown that Zn, which is co-released with insulin, regulates the secretion of glucagons. Increase in the level of Zn is, however, highly toxic to β-cells, and chelation of extracellular and intracellular Zn may be effective in reducing the islet destruction encountered during type 1 diabetes. Recently, it has also been demonstrated that a polymorphism of the zinc transporter ZnT-8, specifically expressed in β-cells, is genetically linked to human diabetes type 2. Thus, a complex picture of Zn acting as an essential ion but also having a toxic effect emerges. It also suggests that changes in serum Zn levels are more indicative of some metabolic complications of type 2 DM than of periodontitis itself. The results our study indicate that low serum Zn level may probably be a factor for the poor wound healing and insulin resistance in type 2 DM with periodontitis.

It has been reported by Paolisso and Barbagallo[21] that the less availability of intracellular Mg results in decreased tyrosine kinase activity and its supplementation could recover insulin sensitivity. Findings also suggest that hypomagnesemia could aggravate insulin resistance and predisposes diabetic patients to the pathogenesis of atherosclerosis. The consequences reported in our study make it obvious that increased serum cholesterol in type 2 DM with periodontitis reduces the serum concentration of Zn, Mg, and HDL-c. Barbagallo et al.,[22] in their experimental studies, observed that low Mg levels have been related to insulin resistance and diabetic complications. Zn along with Mg helps to trigger insulin action and entry of glucose within the cells.

In the present study, increasing BMI was not associated with the serum levels of Zn and Mg. The mechanism whereby cholesterol affects Zn and Mg metabolism may be related with the defect in the absorption process. Mg is a crucial metal ion that catalyzes the enzymatic reactions in all phosphate transfer reactions through the formation of Mg–ATP complexes. Mg and Zn are reported to possess antioxidant property.[23] Antioxidants catalyze the breakdown of reactive oxygen species and have a protective cellular function when blood glucose levels are high. Thus, high levels of Zn in the body may prevent diabetic patients to develop periodontitis. This was supported by our study findings that a significantly decreased mean serum levels of Zn and Mg in type 2 DM with periodontitis than in type 2 DM without periodontitis (group II), and in non-diabetic patients with periodontitis (group IV), confirming that Zn and Mg deficiency might play a role in the development of DM. A decrease in Mg level further in type 2 DM with periodontitis increases the risk of producing oxidized LDL, which is believed to be dangerous, and the most pathogenic forms of lipids leading to glucose-dependent oxidation of LDL-c.[24]

Type 2 DM with periodontitis could cause systemic inflammation and deterioration of insulin resistance, associated with hyperlipidemia, through the production of inflammatory cytokines. Furthermore, a higher reactive oxygen species (ROS) and O2·− production have been reported in patients with hyperlipidemia.[25] All forms of DM are characterized by chronic hyperglycemia and the development of specific microvascular pathology.[26,27,28] Hyperglycemia is accompanied by hyperlipidemia in diabetes.[29] A combination of hyperglycemia and hyperlipidemia stimulates macrophage proliferation by a pathway that may involve the glucose-dependent oxidation of LDL. Elevated LDL levels are one of the most important risk factors for atherosclerosis and cardiovascular diseases. The oxidized LDL is formed by oxidative stress and leads to endothelial activation and injury resulting in an inflammatory response that leads to recruitment, activation, and migration of monocytes through inter-endothelial gaps to the subendothelial region. ROS enhance oxidative modification of LDL to oxidized LDL. Oxidized LDL also results in generation of ROS from a variety of cell types and contributes to oxidative stress.

Decreased serum HDL-c has been associated with periodontal inflammation.[30] HDL-c has the ability to promote the efflux of excess cholesterol by macrophages and non-macrophages and return it to the liver for excretion. HDL is considered to have an antioxidant feature in normal conditions, but during systemic inflammation, the protective character of HDL-c can diminish to a point where it becomes pro-inflammatory. The antioxidant and anti-inflammatory activities of HDL-c are associated with protection against inflammation. HDL-c is known to regulate the inflammatory processes via several key mechanisms, allowing us to draw conclusions of its protecting association with periodontal inflammation. Periodontal pathogens may affect the protective characteristics of HDL-c. Serum HDL-c may be regarded as a marker of susceptibility to periodontal inflammation, and low HDL-c level is considered to be a known risk factor for cardiovascular diseases. It has been suggested that inflammation damages the apolipoprotein A-1 (apoA1) of HDL-c and leads to a reduction in its amount and the paraoxonase anti-inflammatory enzymes associated with HDL-c. Thus, the protective role of HDL-c may be related not only to the level but also to the quality of HDL-c.

The anti-inflammatory and antioxidative effects and atheroprotective properties of HDL are well documented and include inhibition of LDL oxidation, reduction of inflammatory cytokines, and protection against oxidative stress. An increase in the circulating concentrations of HDL, therefore, may be protective in the metabolic diseases featuring inflammation and premature atherosclerosis. However, there is an increasing body of evidence that there are circumstances in which HDL may not be protective, and may in fact paradoxically promote vascular inflammation and oxidation of LDL.[31] Therefore, the correlations found between HDL and periodontal parameters in the present study may be indicating that HDL plays a protective role; however, it can have a pathologic effect at a certain point. The cause of lipid alteration among type 2 DM patients has been attributed to differential insulin distribution which leads to increased LDL-c and triglyceride production through hepatic hyperinsulinemia, accompanied by decreased catabolism of triglyceride-rich lipoprotein as a result of relative peripheral insulin deficiency. This implies that sustained lowering of triglycerides could delay the progression of periodontitis.

The lipoprotein, HDL-c, has been found to be effective in binding and neutralizing lipopolysaccharides (LPS) of gram-negative bacteria, thereby limiting the expression of cytokines and lipid peroxidation.[32] LPS cause widespread endothelial damage in the hypercholesterolemic condition. Low concentration of LPS inhibits the expression of scavenger receptor activity on human monocyte derived macrophages, but it has no effect on LDL receptor activity. LPS bind to lipoproteins, and the LDL-LPS complex taken by macrophages is not degraded. These results emphasize the understanding that Zn and Mg deficiency has been a plausible factor for hyperlipidemia.

CONCLUSIONS

Zn and Mg levels can be an important risk factor for type 2 DM with periodontitis. The suggestion of a link between Zn and Mg in type 2 DM and periodontitis provides a testable hypothesis that may produce a novel close-by into the pathogenesis of diabetic complications. We conclude that the impaired metabolism of Zn and Mg in periodontitis patients may contribute to the progression of DM and its complications. Supplementation of trace elements such as Zn and Mg might have utility in the treatment of type 2 DM with periodontitis, thus may help in the control of blood glucose and lipid levels preventing or delaying serious clinical events in these patients. To have a control over glycemic and lipidemic effects, it is very important for type 2 diabetes patients to recognize periodontitis early and take necessary treatment.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

The authors are indebted to the Management, Dr. K. Ravi, MDS (Dean), and Dr. K. Rajkumar MDS (Vice-Principal) of SRM Dental College, Chennai, India, for providing us the laboratory facilities to carry out the experimental work.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Morimoto-Yamashita Y, Ito T, Kawahara K, Kikuchi K, Tatsuyama-Nagayama S, Kawakami-Morizono Y, et al. Periodontal disease and type 2 diabetes mellitus: Is the HMGB1-RAGE axis the missing link? Med Hypotheses. 2012;79:452–5. doi: 10.1016/j.mehy.2012.06.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Anjani Kumar P, Vijaykumar S, Chandra A, Kopal G. Association between diabetes mellitus and periodontal status in north Indian adults. Eur J Gen Dent. 2013;2:58–1. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rajhans NS, Kohad RM, Chaudhari VG, Mhaske NH. A clinical study of the relationship between diabetes mellitus and periodontal disease. J Indian Soc Periodontol. 2011;15:388–92. doi: 10.4103/0972-124X.92576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Thomas B, Kumari S, Ramitha K, Ashwini Kumari MB. Comparative evaluation of micronutrient status in the serum of diabetes mellitus patients and healthy individuals with periodontitis. J Indian Soc Periodontol. 2010;14:46–9. doi: 10.4103/0972-124X.65439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jayawardena R, Ranasinghe P, Galappatthy P, Malkanthi R, Constantine G, Katulanda P. Effects of zinc supplementation on diabetes mellitus: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Diabetol Metab Syndr. 2012;4:13. doi: 10.1186/1758-5996-4-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Judith J, Wolfram K, Lothar R. Zinc and diabetes-clinical links and molecular mechanisms. J Nutr Biochem. 2009;20:399–17. doi: 10.1016/j.jnutbio.2009.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sprren K, Keld HJ, Allan V, Sven SS. Zinc absorption in patients with insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus assessed by whole-body counting technique. Clin Chim Acta. 1990;189:13–8. doi: 10.1016/0009-8981(90)90229-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Alena V, Eva T, Marian K, Zdenka D. Altered metabolism of copper, zinc, and magnesium is associated with increased levels of glycated hemoglobin in patients with diabetes mellitus. Metabolism. 2009;58:1477–82. doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2009.04.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fawcett WJ, Haxby EJ, Male DA. Magnesium: Physiology and pharmacology. Br J Anaesth. 1999;8:302–20. doi: 10.1093/bja/83.2.302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jahnen Dechent W, Ketteler M. Magnesium basics. Clin Kidney J. 2012;5:3–14. doi: 10.1093/ndtplus/sfr163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sales CH, Pedrosa Lde F. Magnesium and diabetes mellitus: Their relation. Clinical Nutrition. 2006;25:554–62. doi: 10.1016/j.clnu.2006.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ebel H, Gunther T. Biochemical functions of magnesium. J Clin Chem Biochem. 1980;18:256–69. [Google Scholar]

- 13.He K, Liu K, Daviglus ML, Morris SJ, Loria CM, Van Horn L, et al. Magnesium intake and incidence of metabolic syndrome among young adults. Circulation. 2006;113:1675–82. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.588327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McCarty MF. Magnesium may mediate the favorable impact of whole grains on insulin sensitivity by acting as a mild calcium antagonist. Med Hypotheses. 2005;64:619–27. doi: 10.1016/j.mehy.2003.10.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Corica F, Corsonello A, Ientile R, Cucinotta D, Di Benedetto A, Perticone F, et al. Serum ionized magnesium levels in relation to metabolic syndrome in type 2 diabetic patients. J Am Coll Nutr. 2006;25:210–5. doi: 10.1080/07315724.2006.10719534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Robles NR, Escola JM, Albarran L, Espada R. Correlation of serum magnesium and serum lipid levels in hemodialysis patients. Nephron. 1998;78:118–9. doi: 10.1159/000044895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Friedwald WT. Estimation of the concentration of LDL-c in plasma, without the use of the preparative ultracentrifuge. Clin Chem. 1972;18:499–02. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Konukoglu D, Turhan MS, Ercan M, Serin O. Relationship between plasma leptin and zinc levels and the effect of insulin and oxidative stress on leptin levels in diabetic patients. J Nutr Biochem. 2004;15:757–60. doi: 10.1016/j.jnutbio.2004.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Matsui H, Oyama TM, Okano Y, Hashimoto E, Kawanai T, Oyama Y. Low micromolar zinc exerts cytotoxic action under H2O2-induced oxidative stress: Excessive increase in intracellular Zn2+concentration. Toxicology. 2010;276:27–2. doi: 10.1016/j.tox.2010.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Walter RM, Uriu Hare JY, Olin KL, Oster MH, Anawalt BD, Critchfield JW, et al. Copper, zinc, manganese and magnesium status and complications of diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Care. 1991;14:1050–6. doi: 10.2337/diacare.14.11.1050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Paolisso G, Barbagallo M. Hypertension, diabetes mellitus, and insulin resistance. The role of intracellular magnesium. Am J Hypertens. 1997;10:346–55. doi: 10.1016/s0895-7061(96)00342-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Barbagallo M, Dominguez LJ, Galioto A, Ferlisi A, Cani C, Malfa L, et al. Role of magnesium in insulin action, diabetes and cardio-metabolic syndrome X. Mol Aspects Med. 2003;24:39–52. doi: 10.1016/s0098-2997(02)00090-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Anderson RA, Roussel AM, Zouari N, Mahjoub S, Matheau JM, Kerkeni A. Potential antioxidant effects of zinc and chromium supplementation in people with type 2 diabetes mellitus. J Am Coll Nutr. 2001;20:212–8. doi: 10.1080/07315724.2001.10719034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Southerland JH, Taylor GW, Moss K, Beck JD, Offenbacher S. Commonality in chronic inflammatory diseases: Periodontitis, diabetes, and coronary artery disease. Periodontol 2000. 2006;40:130–43. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0757.2005.00138.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Krause S, Pohl A, Pohl C, Liebrenz A, Ruhling K, Losche W. Increased generation of reactive oxygen species in mononuclear blood cells from hypercholesterolemic patients. Thromb Res. 1993;71:237–40. doi: 10.1016/0049-3848(93)90098-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Brownlee M. Biochemistry and molecular cell biology of diabetic complications. Nature. 2001;13:813–20. doi: 10.1038/414813a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Brownlee M. A radical explanation for glucose-induced beta cell dysfunction. J Clin Invest. 2003;112:1788–90. doi: 10.1172/JCI20501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Southerland JH, Taylor GW, Moss K, Beck JD, Offenbacher S. Commonality in chronic inflammatory diseases: Periodontitis, diabetes, and coronary artery disease. Periodontol 2000. 2006;40:130–43. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0757.2005.00138.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mehler PS, Esler A, Estacio RO, MacKenzie TD, Hiatt WR, Schrier RW. Lack of improvement in the treatment of hyperlipidemia among patients with type 2 diabetes. Am J Med. 2003;114:377–82. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(02)01566-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.McGrowder D, Riley C, Morrison EY, Gordon L. The role of high density lipoproteins in reducing the risk of vascular diseases, neurogenerative disorders, and cancer. Cholesterol. 2011:1–9. doi: 10.1155/2011/496925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ansell BJ, Fonarow GC, Fogelman AM. High-density lipoprotein: Is it always atheroprotective? Curr Atheroscler Rep. 2006;8:405–11. doi: 10.1007/s11883-006-0038-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nofer JR, Kehrel B, Fobker M, Levkau B, Assmann G, von Eckardstein A. HDL and arteriosclerosis: Beyond reverse cholesterol transport. Atherosclerosis. 2002;161:1–16. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9150(01)00651-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]